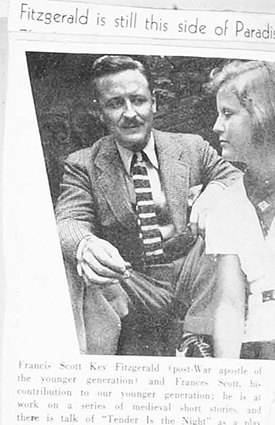

Scott and Scottie, 1937.

In late 1935 Fitzgerald began a series of stories about a girl in her early teens. Just the age of Scottie Fitzgerald at the time, Gwen, with her “bright blue eyes” and eager, curious ways, and her interest in boys, good northeastern colleges, and New York City, has much in common with the Scottie one sees in Fitzgerald’s well-known letters to her.

He wrote to Harold Ober in mid-December,

This story [“Too Cute for Words”] is the fruit of my desire to write about children of Scotty’s age. . . . I want it to be a series if the Post likes it. Now if they do please tell them that I’d like them to hold it for another one [“The Pearl and the Fur”] which should preceed [sic] it, like they did once in the Basil series. I am not going to wait for their answer to start a second one about Gwen but I am going to wait for a wire of encouragement or discouragement on the idea from you.

Although Fitzgerald was recovering from a terrible case of flu during which he spat up blood, he was in good spirits about his work: “I enjoyed writing this story which is the second time that’s happened to me this year, + that’s a good sign.” He worked hard on the story and its revisions through the spring; Ober was enthusiastic about the Gwen idea, not least because he thought it could save Fitzgerald from a return to writing for the movies: “I think it is much wiser for you to work on this series than to try Hollywood so let’s forget that.”

The Post accepted Fitzgerald’s first Gwen story, “Too Cute for Words,” and published it on April 18, 1936, without waiting, as Fitzgerald had wished, for “The Pearl and the Fur,” which was meant to precede it. Instead, they turned down “The Pearl and the Fur,” asking for substantial changes. Discouraged, Fitzgerald worked on the screenplay of “Ballet Shoes” for a while instead, telling Ober, “I’ve spent the morning writing this letter because I am naturally disappointed about the Post’s not liking the Gwen story and must rest and go to work this afternoon to try to raise some money somehow though I don’t know where to turn.” Fitzgerald’s own money struggles are reflected here in Gwen’s family: her father has lost money in the Depression and, evidently, has to deny her many things.

Fitzgerald soon returned to “The Pearl and the Fur,” but declined the suggestions for revisions supplied to him by Ober and Ober’s assistant Constance Smith. Ober disliked the whole taxi ride south, and the desolate beauty of Fitzgerald’s imagined Kingsbridge: “A good deal of the taxicab material seems to me improbable. . . . I have checked up on the subway station at Kingsbridge and 230th Street and it is as closely settled as any part of New York City. The subways leave every three or four minutes. If anyone were in a hurry to get from 230th Street to 59th Street one would never think of taking a taxicab and there are no subway terminals that are in unpopulated districts as you describe.” Smith objected, “Why would anyone take a chinchilla coat to the West Indies in Spring?” When the Post rejected the story again, Fitzgerald refused to resubmit it there. Ober’s files indicate that three versions of it were destroyed on May 14, 1936. The Post did publish one more story featuring Gwen, “Inside the House,” on June 13. Six days earlier, “The Pearl and the Fur” had been sold to the Pictorial Review for $1,000, with the characters’ names changed so it would no longer be a competing “Gwen story.” It never appeared, and the Pictorial Review—at the beginning of the decade a popular women’s magazine with a circulation of 2.5 million—failed in the spring of 1939, a casualty of the Depression.