On July 16, 1969, a Saturn V rocket blasted skyward from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were tucked into a capsule high atop the giant rocket. Ten years earlier, a Soviet cosmonaut had made headlines by flying in Earth orbit. Now, the American space program was aiming far higher. Apollo 11 was on its way to the Moon.

The launch went off like clockwork. Eleven minutes later, when Apollo reached Earth orbit, a check showed that all systems were “go.” The next big moment came when the ship reached the proper point in its orbit. The rocket’s third stage fired and kicked the astronauts moonward. Ahead lay a 238,000-mile (382,942-kilometer) journey.

Over the next three days, Apollo 11 left Earth far behind. Ahead loomed the dark orb of the Moon, backlit at times by a bright halo of sunlight. Collins fired the service module rocket, slowing Apollo 11 to 3,600 miles (5,792 kilometers) per hour. Captured by the Moon’s gravity, the spaceship settled into lunar orbit. “The view of the Moon . . . is really spectacular,” Armstrong said. “It’s a view worth the price of the trip.”1

Leaving Collins to pilot the command module Columbia, Armstrong and Aldrin crawled into the lunar module. Eagle’s inside paneling had been stripped away. The design saved weight but exposed a jumbled mass of wires and pipes. As Aldrin put it, the lander was “about as charming as the cab of a diesel locomotive.”2 After the central command in Houston gave the mission a “go,” Collins released the lunar module. “The Eagle has wings!” Armstrong exclaimed as the clumsylooking lander floated free.3

Eagle, the Apollo 11 lunar module, is photographed from Columbia in its landing configuration during lunar orbit.

While the world waited, spellbound, Eagle started its descent. All seemed well until a warning light flashed on the control console. Back on Earth, engineers pinpointed an overworked computer. Guidance officer Stephen Bales studied the report and told Armstrong to keep going. A second alarm sounded minutes later. Again, Bales said there was no need to abort.4 At this point, Eagle hovered just 500 feet (152 meters) above the surface.

Armstrong took one look at the programmed landing site and shook his head. Eagle was headed toward a crater littered with large boulders. Setting down there would almost surely wreck the module. Armstrong took over the controls and searched for a safer spot to land.

Houston broke in to sound a new warning: “Sixty seconds!” Eagle was running low on fuel. If they did not land quickly, the astronauts would be forced to abort the landing. Eagle’s design did not allow them to tap into the fuel reserved for their ascent.

Long months of training had prepared the crew for this moment. Armstrong grasped the joystick and steered Eagle toward a smoother landing zone. As Aldrin called out speed and distance, he flew lower. Now they were in the “dead man’s zone.” If they ran out of fuel here, they would crash before they could fire up the ascent engine. At 40 feet (12 meters), Eagle began kicking up dust that had not been disturbed for a billion years.5

A moment later, Eagle settled gently onto the Sea of Tranquility. As Aldrin took his first good look at the bleak moonscape, Armstrong relayed the news to Mission Control. “Houston,” he called, “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”6

Mission Control checked the data flowing in from Eagle’s sensors. If the soil had been too soft, Armstrong would have been told to take off at once. The data, however, showed that the footing was solid. Eagle was down safely. With the tension broken, the crew took a well-earned break. Aldrin began by asking his audience on Earth to join him in a brief religious observance. Next came the first meal ever eaten on the Moon. The menu featured bacon squares, sugar cookies, peaches, juice, and coffee.7

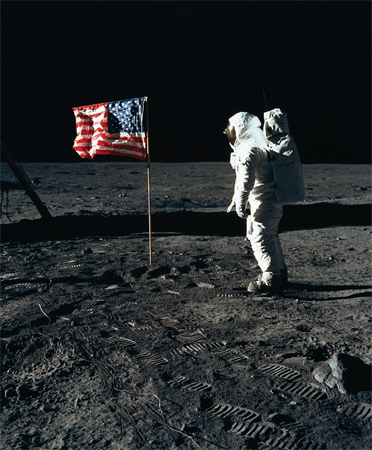

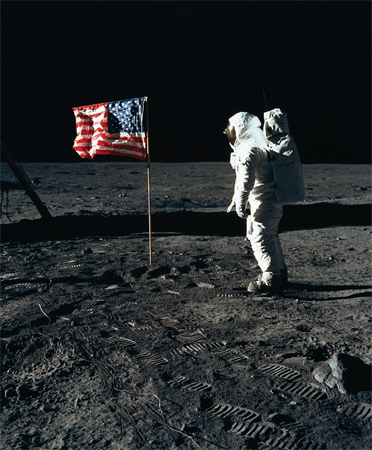

Their rest break over, the astronauts turned to the task at hand. Piece by piece, they checked out and donned their moonwalk gear. When Armstrong stepped out of the hatch, he was sealed inside a shiny white space suit. A life-support system was strapped to his back. On Earth, he would have tipped the scales at 380 pounds (172.4 kilograms). On the Moon, with a gravity one sixth that of Earth, he weighed just 60 pounds (27.2 kilograms).8

Neil Armstrong guided the Eagle to a smooth landing on the Sea of Tranquility. In this photo, Buzz Aldrin removes equipment from the lunar module that the two astronauts will use for their scientific experiments.

Neil Armstrong took the first step on the Moon at 10:56 P.M. as millions watched on television. This is one of the footprints that Buzz Aldrin left on the lunar surface.

At 10:56 P.M., Neil Armstrong earned a special place in history. As a television camera whirred, the command pilot stepped onto the Moon. On Earth, millions of people heard him speak the line he had written for this moment. “That’s one small step for man,” he said, “one giant leap for mankind.”9