The Saturn V rocket booster ignites, launching Apollo 11 skyward on the first leg of its flight to the Moon.

The crowds gathered near Florida’s Cape Kennedy long before dawn on July 16, 1969. By the time the Apollo 11 crew had eaten a steak-and-eggs breakfast, half a million people were on hand. Millions more turned on their television sets to watch the launch. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were going to the Moon. No one wanted to miss this historic moment.

Behind the scenes, flight controllers hunched over their computers. Every calculation and every setting had to be double-checked. On the launchpad, workers pumped propellant into the Saturn V’s huge tanks. Given the same amount of fuel, a light truck could have driven around the world four hundred times.1 Inside Columbia (the crew’s name for the command module), technicians checked banks of instruments, switches, and signal lights. Only two glitches showed up—a leaky valve and a faulty warning light. Both were quickly repaired.2

The space-suited astronauts strapped themselves into their seats. A final check showed that all systems were “go.” Almost exactly on time, Saturn’s five first-stage engines roared to life. Slowly at first, and then faster and faster, Apollo rose into the morning sky. The Moon mission was on its way.

With Collins at the controls, Apollo settled into a low Earth orbit. Saturn’s first two stages dropped away, leaving stage three to propel the spacecraft moonward. After running a last series of checks, Collins restarted the stage-three engine. A six-minute burn put Apollo on a course that would intercept the Moon as it circled the earth. When he reached an escape velocity of 25,000 miles (40,225 kilometers) per hour, Collins detached the stage-three booster. Then he turned the ship and extracted the lunar module, Eagle, from the booster. With Eagle safely docked, the crew settled in for the three-day flight.3

The next job was to put Apollo into a “barbecue roll.” This slow spin would prevent the sun from frying the ship’s electronics on the side exposed to its rays. Their work caught up for the moment, the astronauts stripped off their space suits. At supper time, they used a hot-water gun to prepare a meal of chicken salad, applesauce, and freeze-dried shrimp cocktail. Then they shaded the capsule’s windows, dimmed the lights, and stretched out in sleeping bags.4

The hours passed quickly. Two days into the flight, Armstrong and Aldrin crawled into the lunar module. Eagle’s tiny cabin, they said, was about as big as two phone booths. Both men smelled burned wiring; however, their instruments showed that all was well. The inspection completed, the men returned to Columbia. The time for lunar orbit insertion (LOI) was approaching.

The Saturn V rocket booster ignites, launching Apollo 11 skyward on the first leg of its flight to the Moon.

On July 19, the order to go for LOI came through. As Apollo slipped behind the Moon, Collins fired the engine that reduced the shuttle’s speed. The goal was to allow the spacecraft to be captured by the Moon’s gravity. If the maneuver failed, Apollo might never see Earth again. Those worries faded as the six-minute burn did its job. When Mission Control in Houston asked for a report, Collins was all smiles. “It was like . . . it was perfect,” he said.5

As Apollo 11 glided around the Moon, the astronauts returned to Eagle to continue their preparations. More checklists followed as the pilots flipped switches and exchanged data. After sealing the hatches, Collins received a thumbs-up from Houston. “You are go for separation, Columbia,” Mission Control said.6

A moment later, Columbia backed away with a loud thump. As Eagle floated free, Armstrong and Aldrin stood side by side at the controls. Elastic cords tethered them to the tiny deck. Sixty miles (97 kilometers) below, the scarred face of the Moon floated past. With more checklists to run through, the astronauts had little time to admire the view. In Columbia, Collins stayed in contact. “I think you’ve got a fine-looking machine there, Eagle, despite the fact that you’re upside down,” he said.7

When all was ready, Armstrong fired Eagle’s descent engine. The lander moved closer and closer to the Moon as its speed dropped. With the Moon looming ever larger, the computer manuevered Eagle into landing position.

Now the astronauts were only 300 feet (91 meters) above the surface. Their speed slowed to just 30 miles (48 kilometers) per hour. When Armstrong saw that Eagle was headed toward a boulder-filled crater, he switched off the computer. Pulling back on the joystick, he skimmed over the dangerous crater. Then, with only thirty seconds of fuel left, he found a safer landing zone. As dust billowed in thick clouds, Eagle settled safely onto the Moon.8

In Houston, the controllers shouted with glee. “Roger. Tranquility, we copy you on the ground,” the capsule communicator (CapCom) told the astronauts. “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. . . . Thanks a lot.”9

After attaching a television camera to the lander, Neil Armstrong took his “small step” into history. No one worried that he had meant to say, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” The moment was too exciting to worry about grammar. With only five months left in the decade, NASA had fulfilled the first half of former president Kennedy’s pledge.

The first moonwalker pulled down his visor to cut the glare as he stepped out of Eagle’s shadow. High above floated the blue sphere of Earth. From this desert moonscape, it looked small and distant. “[The lunar surface] has a stark beauty all its own,” Armstrong told a watching world. “It’s different, but it’s very pretty out here.”10

Aldrin jumped down to the dusty plain nineteen minutes later. He closed the hatch as he left the lander but was careful not to lock it. Armstrong slapped his friend on the shoulder when they met. “Isn’t this fun?” he said with a big grin.11

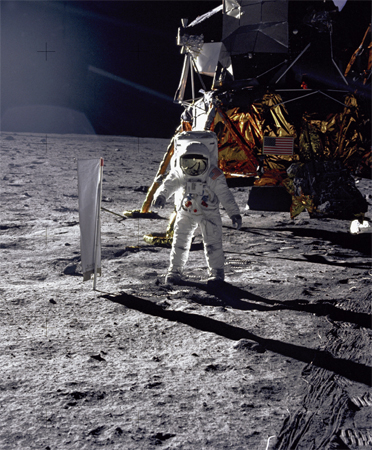

Then it was time to go to work. There were photos to snap, gear to unpack, and experiments to set up. While Armstrong explored a nearby crater, Aldrin snapped open the solar wind panel. That job done, he practiced walking in the light gravity. Each step scattered small sprays of fine-grained lunar soil. Weighing only 60 pounds (27 kilograms) made it easy to move, but hard to stop. Aldrin found that he had to plan ahead several steps if he wanted to stop or turn without falling. Hopping and jumping, he said, made him feel as though he was floating.12

Neil Armstrong snapped this picture of Buzz Aldrin as his partner explored the Moon’s dusty surface.

One of the moonwalking astronauts’ main tasks was to conduct experiments. In this photo, Buzz Aldrin has just deployed the solar wind panel (left).

Their work done for the moment, the astronauts returned to the lander. A television camera captured the moment as Armstrong unveiled the plaque attached to one of Eagle’s landing pads. Signed by President Richard Nixon and the three Apollo 11 astronauts, it read:

HERE MEN FROM THE PLANET EARTH

FIRST SET FOOT UPON THE MOON

JULY 1969, A.D.

WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND13

To complete the ceremony, the astronauts set up an American flag. Hammer as they might, the pole would not penetrate deeper than eight inches (twenty centimeters). Armstrong used his camera to snap a photo of Aldrin as he saluted the flag. A moment later, CapCom called to say that President Nixon wanted to talk to them. It was, NASA said later, the “longest long-distance phone call” ever made.14

“For one priceless moment . . . all the people on this Earth are truly one,” Nixon said on the phone. “One in their pride in what you have done. And one in our prayers, that you will return safely to Earth.”15

“Thank you, Mr. President. . . . It’s an honor for us to be able to participate here today,” Armstrong replied.16

With that, the moonwalkers hurried back to the important tasks that awaited them.