Appetites Return

THE MENU IN THE MESS

The first morning I awakened again in my home, I walked around my few inexpensive rural acres to survey the damage. All the trees looked bare, even though early October in New Orleans doesn’t qualify as fall. The lawn was high with weeds, but so much debris from the surrounding woods had blown over it that picking up the sticks alone would take days. I counted twenty-eight trees down, of which one had grazed the side of my house (doing only insignificant damage).

Mainly what I did while walking around was to try to mentally prepare for what I had planned that afternoon. I would go into town and try to get my head around that much worse situation. New Orleans was now wide open, although many parts of it were under curfew and even larger areas still had no power.

My neighbor Lee warned me about something I wouldn’t have expected: terrific traffic snarls on the North Shore. So many people had moved over there—particularly from wiped-out St. Bernard Parish—that it now took an hour to make a trip that used to take ten minutes. The influx of St. Bernardians was so great that the large Catholic high school in Chalmette (the major town in the parish) had to relocate its campus fifty miles away, to the other side of the lake. That’s where most of its students now lived.

Traffic was indeed heavy all the way across the Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, twenty-four miles spanning open water. It was the only major lake crossing in which Katrina had not opened gaps. The cars were also snarled pretty badly through Metairie, but when I took the fork in the I-10 into Orleans Parish, I suddenly found four open lanes. It was like six o’clock in the morning on Christmas—nobody coming, nobody going. I slowed down. There, on railings and light poles and everything else sticking up, were the soon-to-be-familiar horizontal lines showing how high the flood had gone. The express-way had been under several feet of water.

I exited at the Superdome. My one-room office of the past fifteen years was in a converted warehouse across the street from the stadium. Because thousands of desperate people crammed into it to escape the flood, the Superdome was on television a lot after the hurricane. I knew from that coverage that it had been surrounded by water at least waist-high. The flood in my office reached four and a half feet. The building had already been gutted. My stuff was gone—it had all dissolved into a heap of unsalvageable debris. All my past publications, photographs, and radio tapes—thirty years’ worth—were gone forever. For a moment, I had that free feeling again. I wouldn’t have to drag all that stuff around with me for the rest of my life. Then I had another thought: If this is my greatest material loss from the storm (and it was), then by the standards of my fellow citizens, I was lucky indeed. My luck had to be shared somehow.

I drove around town gingerly (you had to, because nails, glass shards, and other forms of debris were scattered widely on every street) for a couple of hours. Although I had already had a good idea of the extent of the damage, seeing it up close was a mind-bender. The abandoned cars alone did that job. It was necessary to have my mind bent, though, to relate to the people I would encounter who had put up with all this when conditions were much worse.

I met many such people in the following weeks. They were close and not-so-close friends, people I worked with, and relatives. And no small number of the strangers who come to know a person who works in the media. They all felt we had enough in common for them to just walk up and start talking (not that I ever minded that).

The moods ranged from optimism to depression. But they all had in common a fatalism I’d never encountered before in so many people at the same time. We were all coming to grips with the idea that the dreams and goals we had before the hurricane were now irrelevant. Before we could even start thinking about the future, we had to recover from this forced retreat into the past. That was such an overwhelming challenge that you couldn’t even think about it in one piece; you could only take on a little part of it, and try to ignore the rest.

I ran into Mayor C. Ray Nagin at the radio station a couple of weeks after I came back to town. I asked him, “So, how’s it going?” He looked into the corner of the ceiling, gave a helpless-looking smile, and said, “One day at a time!” While I was hoping for something more dynamic and imaginative from New Orleans’s chief executive, I have to admit he was right in step with how all of his constituents felt.

The day of my first look at post-Katrina New Orleans headed toward a dusk that pulled a very dark night behind it. I turned toward home. When I passed in front of Andrea’s, I thought I’d better check in. I was hungry, come to think of it. Chef Andrea—who worked in hotels for decades before he started his own place, and so was accustomed to the idea of remaining open all the time—had been open since mid-September. We exchanged the Katrina hug in a dining room whose carpets were gone, revealing a concrete floor. Unfinished wallboard was nailed to wall studs you could still see here and there. Nevertheless, Chef Andrea had a full house of customers. And that was only because it was early. By the time I left, people were stacked up in the bar, waiting for tables.

Chef Andrea opened a bottle of Cesari Amarone for us to share and launched into his tale of woe. His house got it as bad as the restaurant had. The same foot of water. He was up in arms, as many Metairie people were, about the way the parish abandoned the critical pumping stations during the storm. I told him he was lucky the water stood for only a day or two here, unlike the four or five (or six or seven) feet that sat stagnant for three weeks in Orleans Parish.

His most pitiable moaning, however, concerned his employees. He didn’t have nearly enough of them to serve the number of diners who wanted to dine in his restaurant. The staff that day was an assortment of old pros and not-so-old, not-so-pros from other restaurants. No uniforms. The maître d’ wore denim overalls and a hunting shirt. A couple of chefs from other restaurants wore the white jackets of their home kitchens.

“My pastry chef of almost twenty years left me,” said Chef Andrea. “He told me he could make a lot more money working in construction.” I would hear that story about many other former restaurant employees in the months to follow.

The menu was limited that night. I had veal Romano—like Wiener schnitzel, but with a red sauce. A bowl of turtle soup. It was good enough, but not up to Andrea’s typical standards. I expected that, but I worried about it. Our city’s usual level of culinary excellence certainly would be compromised for some time. Would some jerk food critic from somewhere else swoop in too soon and say New Orleans wasn’t what it used to be?

I hung around Andrea’s for a few hours. Many people invited me to join them at their tables; many Katrina hugs were exchanged, even with numerous people I’d never met in my life. Two themes emerged from the stories these people told. At most tables of two or more couples, one had lost their house in Lakeview or Mid-City or Gentill, and was staying in the damaged but livable Metairie home of the other. The other leitmotif was that all of these people were laughing, telling stories, toasting one another, and otherwise having what appeared to be a celebration. When I tuned in and listened to what they were saying, the real nature of their festivity came out. They were unloading stress. They were relieved to have returned to a beat-up lifestyle that was nevertheless recognizable and still in one piece, and they took as much of it as they could to convince themselves that the world had not ended.

Before the dinner rush, Chef Andrea and I planned an Eat Club dinner for the following week. What better way to demonstrate that the New Orleans food scene was alive and well than to resume Eat Club evenings? Even without the benefit of the radio show to promote the dinner (I got the word out through the Web site), we sold it out, to about forty diners, in less than a week. We had five courses in a room with unpainted wallboard, no carpets, and stackable chairs. The menu:

Antipasto Misto

Shrimp Caprese

Fresh Pasta Marinara, Alfredo, and Pesto

Red Snapper Basilico

Tiramisu

All the fish was fresh and local, which seemed like a miracle at the time. Even as we told one another our Katrina stories—some of which were heart-stopping—not a long face was to be seen. The price for attending this dinner was whatever people wanted to pay, with any excess over what Chef Andrea charged going to a fund for displaced restaurant workers. More money went to the charity than to the restaurant. The food was terrific, and the loving mood was overwhelming.

Then came the e-mail from the concerned strangers who wanted me to join them at Restaurant August. That dinner was, for me, the confirmation of an idea that took root in my mind from the moment I arrived back in town: Not only would the culinary imperative of New Orleanians survive Katrina, but it would be one of the strongest forces pulling the city back together again.

I wrote the following words about this reassuring power. They were quoted in at least two other post-Katrina books I know of, so I may as well use them in my own:

New Orleans’s greatest asset is its uniqueness. We must maintain that at all costs. It is what makes people love our town . . . and, often, know more about the city than the locals do. These people will not break faith with us.

We have a few things to do.

1. We must believe in a bright future. We must maintain the image of the unique culinary culture of New Orleans, both here and elsewhere. Let the world know that we’ll be back, and that they’ll have something they’ve never tasted in their lives waiting for them.

2. We must organize and plan. The restaurants and diners of our city need to communicate, create a plan for a big renaissance, and come back with the biggest culinary special event in the history of our country.

Say it, and it becomes true. I say the serious eaters of the world cannot live without New Orleans food. And that when we give it to them again, it will be the best we’ve ever cooked.

Some of my readers replied to that and other hopeful pieces of mine with a much less sanguine outlook. How could I blame them? There was surely loads of evidence that rebuilding would be the battle of our lives.

Hardly a weekend goes by without a festival celebrating some element of local culture. There’s always much food to be had. Not just hot dogs and popcorn, but the full menu of local eating, often cooked by restaurant chefs. Many of the festivals celebrate food per se. These include (to name but a few) the Gumbo Festival (several of those, actually), Crawfish Festival, Andouille Festival, Greek Festival, Oyster Festival, Jambalaya Festival, Crab Festival, and the unlikely but long-running Shrimp and Petroleum Festival.

Thousands of people show up for each of these, with eating as their primary goal. And these are the smaller ones. The big festivals go on for weeks and shut down parts of the city.

Here’s a list of the festivals, with an emphasis on the ones with the best food.

January 6, the Epiphany, or King’s Day is the official start of the Carnival season. It lasts through Mardi Gras (the day before Ash Wednesday), with the pitch of celebration rising as it goes.

Mardi Gras is the definitive New Orleans festival. It runs at full tilt for at least the two weeks before Ash Wednesday. Mardi Gras parades fill the streets not only in the city itself but throughout the suburbs and even into some exurban towns. Mardi Gras is not famous for its food, but it does have a distinctive local icon: the king cake, a circular, sweet yeast bread decorated in Mardi Gras colors of purple, green, and gold.

New Orleanians get tired of Lent quickly. St. Joseph’s Day, March 19 and the week around it, bring parades and the unique St. Joseph’s altars. Those are set up in homes and restaurants, and seem to be constructed entirely of food.

Next, in the second weekend of April, comes the French Quarter Festival, with food and music scattered throughout the namesake historic district. The organization that puts this on also does the Satchmo Festival, a smaller but growing weekend August event that has more emphasis on music than food. The same organization offers the Reveillon (more on that later) in December. The schedules for all are at fqfi.com.

The last weekend in April and the first one in May bring the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, which is now almost as big as Mardi Gras. Although music is the centerpiece, the food is every bit as great a draw.

The week before Memorial Day is the New Orleans Wine and Food Experience, the most sophisticated food festival of all. Its tastings of chef-prepared dishes and hundreds of wines have grown so large that only the Superdome is big enough to hold it anymore.

That weekend is shared with the Greek Festival, which is extraordinary. Although New Orleans has never had many Greek restaurants, the Greek Orthodox community (the oldest in America) is large and enthusiastic. It seems that every Greek in town comes to this, and the food is marvelous, especially the pastries and the whole roasted lamb. Specialty food festivals continue through June, and start trailing off as the heat rises.

The year ends with the month-long Reveillon, in which some 40 restaurants offer holiday-themed dinners at attractive prices. This is the revival of a 200-year-old Creole holiday tradition. For many locals, it wouldn’t be Christmas without attending one or more Reveillon dinners.

King’s Day |

January 6 |

|---|---|

Mardi Gras |

The day before Ash Wednesday |

St. Joseph’s Day |

March 19 |

French Quarter Festival |

Second week in April |

New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival |

Last weekend in April and first weekend in May |

New Orleans Wine and Food Experience |

The week before Memorial Day |

Greek Festival |

Memorial Day weekend |

Reveillon |

The month of December |

Few places caught more of the brunt of the storm than Plaquemines Parish. That’s just south of New Orleans, on the narrow neck of land that hugs the Mississippi River in its final miles before it reaches the Gulf of Mexico. In early November, two and a half months after the hurricane, the Louisiana Seafood Marketing Board organized an industry and media excursion to Empire, the center of the parish’s vast oyster-producing area. Empire was also the first place Hurricane Katrina landed in Louisiana.

Representatives of commercial fishing interests—the oyster guys, the shrimpers, the seafood dealers—related their plight as the bus made its way down. The boats, the docks, the processing plants, the icehouses, and every other part of their livelihoods were either severely damaged or gone completely.

The citrus stands, which that time of year would usually be filled with Plaquemines oranges and satsumas, were all closed. But the orange groves themselves looked okay. Just a few trees down, lots of oranges on the ground. The houses and other structures didn’t look especially worse than what I’d seen elsewhere around town.

But just a minute or two past this scene, we reached a police checkpoint. Identification as a resident was required for anyone to go any farther, and even then you had to be out of the area by dark. We would soon see why. Our police escort led us to the old highway that runs next to the river levee and into a town called Diamond.

The destruction in Diamond was an order of magnitude—perhaps two—worse than anything I’d seen so far. Nearly every house was off its foundation, placed at strange angles to the road. A large oyster truck was hanging from a tree, a few feet off the ground. Everything was wrecked beyond any dream of repair. And it went on like that for miles.

“That was Ground Zero,” one of the fishermen said. “When you get to Empire, you’ll see Ground Sub-zero.” This was no exaggeration. In Empire, boats were on top of houses. Houses on top of trees. Quite a few houses were half a block away and across the street from their addresses. And those were the ones that were still in one piece. Many houses were now just boards scattered all over the place.

The most bizarre spectacle of all involved the fishing boats. They were strewn all over dry land. The ones still in the water were in insane tangles with one another. Two gigantic “pogy boats”—vessels that scoop up menhaden, the fish used for cat food—had been carried by the storm surge halfway up a high-rise overpass. They were now parked there, seeming to ask, “So what in the hell are you going to do about this?” Strangely, what most of us did was laugh. It was like a scene out of a movie with very heavy special effects.

My friend Harlon Pearce was along for this tour of Empire. He’s in the seafood wholesale business and he lost a million dollars’ worth of fish when the power went off during the storm at the cold storage warehouse. “I’d tell you what it was like to clean that up, but really, the quarter million pounds of chicken in there was even worse.”

I did my best to compute all this on the trip back to Metairie. There, the group lunched at the Acme Oyster House. We started with, of all things, raw oysters on the half shell. The Seafood Marketing Board guys got up and explained that, despite what we’d just seen, there was plenty of Louisiana seafood out there. And that it was not only without taint (all the authorities vouched for that), but of unusually excellent quality. Shrimp and crabmeat especially. The oysters were certainly fine.

This was a pleasant surprise, two months after hearing predictions that it would be years before we’d eat Louisiana oysters again. In fact, I had had my first oysters a couple of weeks earlier, when Dickie Brennan and I had hesitated for a moment before devouring the first oysters to arrive at his Bourbon House since the storm.

RELUCTANT RETURNEES

On my way home from the Empire expedition, I got a call from Mary Ann. She and Mary Leigh were on the fourth and final day of their long-delayed return home—about 200 miles away. They would stop at Leatha’s, the barbecue joint they like in Hattiesburg.

This was good, I thought. I could get home, take a shower and a nap, and make something special—chocolate mousse, which they love—to greet my girls on their homecoming.

They were charmed by my mousse, the flowers, the clean house, and some other gifts. But the charm didn’t overcome their discomfort in the environment formerly known as home. All those trees on the ground. And all those gaps and broken branches in the trees that had managed to remain upright. The ripped-up buildings. The dead power lines snaking across roads everywhere. They were talking about going back to Washington before the evening ended. They didn’t—not right away.

Meanwhile, back in DC, my son Jude was thriving as a boarding student at Georgetown Prep. After the holidays, Mary Leigh resumed her freshman year at the Academy of the Sacred Heart, an excellent school she’d chosen herself two years earlier. But it wasn’t the same for her. Part of the problem was having to pass through a large devastated area of the city to get to school every morning. How could she not compare that with the beautiful Stone Ridge Academy, the school that had taken her in following our evacuation to Washington? After a few months, although her grades stayed at their usual top level, she could no longer handle going to Sacred Heart. Or living in New Orleans. She and Mary Ann moved back to Washington. They rented an apartment, and Mary Leigh finished the school year at Stone Ridge—which not only welcomed her back but gave her and two other New Orleans girls an award for courage at the commencement. They remained in DC for most of the next school year.

I remained in New Orleans alone. What else could I do? I needed to get back to work. Mary Ann felt that I hadn’t given the idea of living in DC permanently a chance. But, given the extreme specialization of what I do, I would never be able to earn the money in any other city that I did in New Orleans—at least not in the short term. And once it became clear to me not only that I could continue my career successfully in New Orleans, but that I was playing a role in the recovery, leaving town became anathema.

Many New Orleans families had to deal with this issue. Businesses and jobs were moving out of town, taking with them a lot of people who really didn’t want to move. Many families were split, both physically and emotionally—sometimes permanently. As of this writing we seem to be doing OK. One day at a time, to quote the mayor.

By the post-Katrina three-month mark, my New Orleans Restaurant Index had zoomed past 200, even with vast areas of the city still uninhabitable by either restaurants or their customers. Restaurants were opening right and left. The ones that had already opened were doing such overwhelming business that many others—including no small number of brand-new ones—were motivated to get into the act.

As I noted earlier, the first major restaurants that reopened were reluctant to serve gourmet dishes, offering home-style cooking instead. That didn’t last long, not only because their customers wanted the chefs’ real food, but also because plenty of home-style restaurants were already back open to serve that hunger. (We all wanted to eat our red beans, but not when we went to Restaurant August or Emeril’s.) In fact, the small neighborhood cafés soon constituted a majority of the restaurants on the Index. The margin has continued to widen. There’s never been a time when New Orleans had so many poor boy shops, blue-plate-special cafés, and other neighborhood eateries. Or so many ethnic restaurants, particularly in the Asian category.

I had a hard time persuading visiting journalists of that statistic, however. Their first question always seemed to be, “So, the famous restaurants in the French Quarter are coming back, but it’s a real shame about all the mom-and-pop places washed away by Katrina, isn’t it?” When I told them that the situation was, in fact, the other way around—that the French Quarter places, facing years of much-reduced tourism, were in far greater peril—they hardly knew what to say next. Some of them repeated the question, trying to get me to agree with their a priori conclusion that the little restaurants surely were doomed. I pointed them to my Index, which included names, addresses, and phone numbers for all the restaurants, in case they wanted to check out my assertion that the corner cafés were thriving.

The most inspiring example of that comeback was what happened in the large Vietnamese community in New Orleans East. The storm surge didn’t need a levee break to do its damage there. It rolled right over the levees and pushed ten or more feet of water across the entire area. What’s more, that part of town was much closer to the eye of the storm and its maximum winds. It was a wipeout.

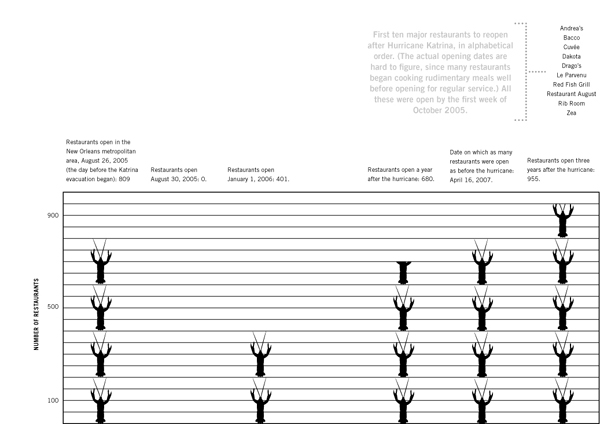

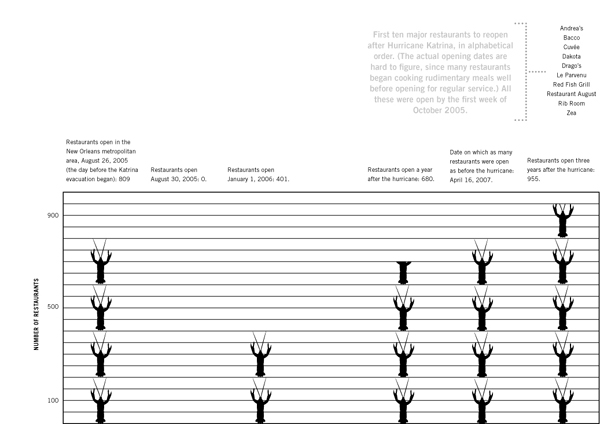

First ten major restaurants to reopen after Hurricane Katrina, in alphabetical order. (The actual opening dates are hard to figure, since many restaurants began cooking rudimentary meals well before opening for regular service.) All these were open by the first week of October 2005.

Andrea’s Bacco Cuvée Dakota Drago’s Le Parvenu Red Fish Grill Restaurant August Rib Room Zea

Restaurants open in the New Orleans metropolitan area, August 26, 2005 (the day before the Katrina evacuation began): 809

Restaurants open August 30, 2005: 0.

Restaurants open January 1, 2006: 401.

Restaurants open a year after the hurricane: 680.

Date on which as many restaurants were open as before the hurricane: April 16, 2007.

Restaurants open three years after the hurricane: 955.

Fans of the neighborhood’s cuisine were most upset about Dong Phuong, a restaurant beloved not only for its big menu of Viet dishes, but also for baking wonderful French bread for its poor boy–like banh mi sandwiches. We thought it was surely the end for that and the other restaurants out there in the East. Then, less than two months after the storm, we saw the first of the Vietnamese restaurants in the area reopen. That was soon followed by other businesses and the return of most of the residents. They just dug in and fixed things, not bothering to wait around for insurance settlements and government assistance. It wasn’t what it had been—a burgeoning community of people farming, fishing, and selling the unique products of their culinary culture—but it was back in business.

The New Orleans dining puzzle had a lot of missing pieces, all right. But diversity, and even diversity of diversity, was not one of them. If you looked even a little, by the end of that awful year 2005 you could find any kind of restaurant that had been there before the storm.

BREATHING THE AIR

The week of the Marys’ temporary return brought another resumption of life as I had known it. WWL Radio asked me to return to the air that weekend. The logistics, by necessity, were rather peculiar. The owners of our badly damaged building next to the Superdome wouldn’t allow us back in. For many weeks, we shared the facilities and personnel of our most strident competitors, in the studios of their affiliates in Baton Rouge. This meant a ninety-minute commute each way to do the radio show. But I was relieved, and eager to do it.

The host who preceded me said, “Is this your first show back? Wow. Get ready. You’re not going to believe what you’re going to hear. These people are out of their minds with rage.”

“I’m not going to get into any of that stuff,” I said. “I’m going to do a food show, just like always.”

“You won’t get away with it,” he said. “They want to cut heads off, and you can’t stop them. Even the sports guys are talking about FEMA and the Corps of Engineers and all that.”

I opened the mike and explained my intentions. I gave the latest number of restaurants open, named the ones that had recently returned, and asked about any eateries the listeners may have visited. And, I wanted to know, if you’re back home but your kitchen is a mess, what are you cooking, and how? If you have a wine collection, how did it fare? And other stuff like that.

The first caller was convincing. “Thank God we can stop talking about levee breaks and insurance problems!” he said. “We’re sick of hearing about that twenty-four hours a day! I’m so happy to hear your voice! Now—when is Commander’s Palace going to reopen?” Here was someone who agreed that food could heal us.

Everyone else who called during the next four hours felt the same way, save for one caller who tried to sneak in with a flood-insurance complaint. For the next month, I did shows of between four and six hours every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I received no more hurricane-distress calls. Even more reassuring, nobody called to demand that this frivolous gourmet stuff be taken off the air while so many people were still suffering. It was great to learn that even stressed New Orleanians could still compartmentalize. Either that, or they knew that without our cooking, music, and the rest of our local culture, we were of little value to anyone.

By December 2005, the radio station was back in New Orleans, and I was back on the air every day on WSMB. The management liked having at least a little optimism on WWL, whose other shows remained full of desperation and anger. They kept me on the air there on Saturdays. Three years later, I’m still doing that extra show on the big-gun station.

Working in our old studios was disturbing. We were the only occupants in the formerly full twenty-six-story building. The building was missing about half of its windows and no longer had regular janitorial service. Trash and leaves blew around in the lobby. Sometimes the power or the water went out. It was like a scene from an Armageddon movie, with a few survivors huddled in an abandoned skyscraper. We didn’t move to new quarters until more than a year has passed, and I was the last host to move to the new digs. That was my version of moving out of a FEMA trailer and back into a real house.

RECIPE

Whole Flounder Stuffed with Crabmeat

Bruning’s opened at West End Park in 1859 and remained popular and excellent, run by the same family, until it and everything else at West End was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. Bruning’s great specialty was stuffed whole flounder. The restaurant may be gone (although maybe not forever), but the dish lives on. Use the biggest flounder you can find. (Fishermen refer to those as “door-mats.”) I use claw crabmeat for the stuffing, because it has a more pronounced taste.

Stuffing

½ stick butter

¼ cup flour

3 green onions, chopped

3 cups shrimp stock

1 Tbs. Worcestershire sauce

1 lb. claw crabmeat (or crawfish, in season)

¼ tsp. salt

Pinch cayenne

Flounder

4 large whole flounder

1 Tbs. salt-free Creole seasoning

1 tsp. salt

1 cup flour

2 eggs

1 cup milk

½ cup clarified butter

1 lemon, sliced

Fresh parsley, chopped

Preheat overn to 400 degrees.

1. Make the stuffing first. Melt the butter, and stir in the flour to make a blond roux. Stir in the green onions, and cook until limp. Whisk in the shrimp stock and Worcestershire, and bring to a boil, then add the crabmeat, salt, and cayenne. Gently toss the crabmeat in the sauce to avoid breaking the lumps.

2. Wash the flounder and pat dry. Mix the Creole seasoning and salt into the flour, and coat the outside of the flounder with it. Mix the eggs and milk together in a wide bowl, and pass the fish through it, then dredge in the seasoned flour again.

3. Heat the clarified butter in a skillet and sauté the fish, one at a time, about four minutes on each side, turning once. Remove and keep warm.

4. Cut a slit from head to tail across the top of each flounder. Divide stuffing among the fish, spooning inside it the slit and piling it on top. Place the flounder on an ungreased baking pan, and put into the preheated oven for six minutes.

5. Place the flounder on hot plates. Garnish with lemon slices and fresh chopped parsley.

SERVES FOUR TO EIGHT.