TOWARDS QUMRAN

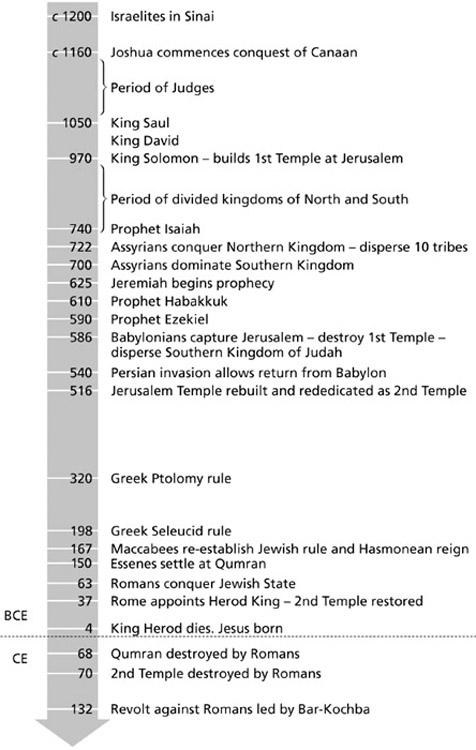

A brief journey through history, covering a period of 1,000 years from the time the Israelites entered Sinai from Egypt, bridges the gap between Moses and the tantalizing Qumran-Essenes, inhabiting a remote corner near the Dead Sea in Israel around the time of Christ. Figure 12 gives the historical landmarks on which to pin an evaluation of how the monastic community at Qumran might be related to the priests of Akhenaten. A fuller description is given in endnote 1 for this chapter.

A brief journey through history, covering a period of 1,000 years from the time the Israelites entered Sinai from Egypt, bridges the gap between Moses and the tantalizing Qumran-Essenes, inhabiting a remote corner near the Dead Sea in Israel around the time of Christ. Figure 12 gives the historical landmarks on which to pin an evaluation of how the monastic community at Qumran might be related to the priests of Akhenaten. A fuller description is given in endnote 1 for this chapter.

When Moses left Egypt to lead the Children of Israel towards the Promised Land, I believe he took with him some of the Akhenaten priests amongst a mixed company of Egyptian nobility, soldiers and general helpers. They, in turn, became the natural guardians of the holy treasures, the Ark of the Covenant…and many secrets.

One group of these priests who left Egypt with Moses were known as the Levites. They were consecrated by Moses to serve in the Tabernacle and eventually formed part of the select priests of the First Temple (built by Solomon in Jerusalem, around 950 BCE).2

THE LEVITE PRIESTS

What the precise role of the priestly Levite guards was between the time of Joshua, the ‘Conquistador’ of Canaan, and the end of Solomon’s reign in the time of the First Temple is unclear. The Torah gives different answers for different periods.

Early on the Levites are assigned the priestly office – the guardians of the Tabernacle (Numbers 1:50) and, in Exodus 32:26–29, as the sons of Levi, they are manifestly warrior priests prepared to use the sword to root out idolatry amongst the Children of Israel.

Other parts of the Bible give them different roles. Deuteronomy 33:8–10 allots the Levites a role as keepers of the Thummim and Urim,*35 teachers of the law, burners of incense and placers of sacrifices on the altar. In earlier traditions they are known as ‘Palace guards’. The Levites, equated with priests in the Bible, are shown special consideration throughout the Torah. It appears that the Levites descended from Aaron, Moses’ Biblical brother, and were to perform the priestly functions, whilst the other Levites were to perform other sanctuary duties (Numbers 18).

Whilst King David ruled, the northern Levite priests based at Shiloh (who claimed descent from Moses) were favoured, but they suffered badly under Solomon and even worse under Jeroboam, giving them every reason to become isolated from the community.

In the time of the Judges and the Kings of Israel, the injunction that priests could only be from Levite stock seems to have been varied: Samuel, an Ephraimite, performed the role of priest when the sanctuary was initially established at Shiloh (I Samuel 1 and 2), and in the time of King David the priests were entitled Zadok and Ahimelech (II Samuel 8:15–18).

Ezekiel 40:46 is even more specific in stating that the position of high priest should be reserved for Zadokites, descendants of the sons of Levi, and it appears that the Zadokite priests dominated the role for several hundred years from Solomon onwards.

PORTENTS OF DISASTER

The period before the invasion from the north by the Assyrians is one of prophecy and castigation of the Jewish people for straying from the path of God, by the line of prophets from Amos, Hosea, Micah and Isaiah during the period 800–700 BCE. As we approach the time of the fall of the First Temple, the prophesying becomes more strident and more doom-laden.3

We see also, before the period of the next invasion from the north by the Babylonians, that there is a movement from within a priestly group to get ‘back to basics’, to return to the teachings of Moses in the deserts of Sinai. A ‘new’ Testament4 is suddenly discovered in the time of King Josiah, who ruled from 637 to 608 BCE, and this is the first hard evidence we have that there were secret texts being kept by the priesthood that were not available to the general populace, or even to the monarchy.

Figure 12: Time line from Sinai to Qumran.

After the capture of Jerusalem by the Babylonians (Chaldeans) and the destruction of the Temple in 586 BCE, the majority of Israelites were taken as prisoners to Babylon. Those that were taken comprised mainly the upper classes and intellectual sectors of the community. (This is one of the reasons why the Babylonian version of the Talmud came to dominate Jewish thinking, rather than the Judaean or southern version.5) The line of the transitional and post-First Temple prophets, commencing with Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Zephaniah, Nahum and Habakkuk, now sang a different tune. Along with condemnation for pagan practices comes the predictions of divine retribution on the enemies of Israel, and the encouragement that the meek and religious will survive.

It is these themes that were taken up, or perhaps originated, by the Essene movement. They are exemplified by the teachings of the Prophet Habakkuk (‘The righteous shall live by his faith’)6 who is believed to have prophesied around 610 BCE. These teachings were of profound significance to the Qumran-Essenes, and are given prominence in their recording in one of the Dead Sea Scrolls – a Midrashic (see Glossary) commentary on the first two chapters of the Old Testament book.

EMERGENCE OF THE QUMRAN-ESSENES

This ‘community apart’ began transforming itself into a separate religious group that was, I believe, the early Essenes; an ultra-religious faction of this sect eventually evolved to become the Qumran-Essenes of the Dead Sea.

We pick up the thread of the priestly guardians of the Covenant before the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem c.586 BCE. It is in this period that the line of priestly inheritance came under greatest threat. The sacred Ark of the Covenant and the treasures of the sanctuary were in jeopardy and, whilst some sacred items had already probably been carried off to Babylon, like the bulk of the Jewish tribes (as the Old Testament asserts), the rest of the treasures may have been hurriedly hidden in the vicinity of Jerusalem. Some of the priestly guardians may have been been able to remain in Judah, others may well have been carried off to Babylon and the region of Damascus. When the Persian King, Cyrus II, overran the Babylonian Empire in c.540 BCE, he gave permission for the Jews to return to their homeland. Not all took up the offer, but of those that did, the priestly guardians would have had every reason to be amongst them. Their first task was to start rebuilding the Temple.

I believe that it was at this stage in history that, under the influence of prophets like Ezekiel and Habakkuk, the Levite priestly guardians became even more estranged from the central control of the Temple’s activities and began reformulating their religious philosophies.

The situation is beautifully summed up by Richard Friedman in his brilliant book Who Wrote the Bible? 7 The Aaronic priests had been dominant in the south, in Judah, but are confronted with the arrival of refugees from the fallen northern kingdom. They bring rival priests, who trace their ancestry back to Moses, and Biblical texts that denigrate Aaron. The theme of disputing priests, begun in the deserts of Sinai, continues. The Aaronic priests of the south win the initial struggle and proceed to rewrite some of the holy texts to reinstate Aaron and his descendants as the true priestly line that should have the sole right to officiate in the Temple.

Conventional understanding is that the Qumran-Essenes ‘emerged’ around 200 BCE, but a few scholars now accept that their influences and writings are based on much older experience. One of these scholars is the highly respected Ben-Zion Wacholder, a partially blind Professor from the Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati. At the ‘Dead Sea Scrolls – Fifty Years After Their Discovery’ Congress, in Jerusalem in July 1997, he created a real stir by standing up and announcing that he believed Ezekiel was ‘the first Qumran-Essene’. In his paper Professor Wacholder drew attention to what he called enigmatic lines in the ‘Ezekiel’ Dead Sea Scrolls, one of which refers to ‘the wicked of Memphis whom I will slay’. Enigmatic indeed! Why would God be interested in avenging people in Egypt?

If my contentions are correct, the northern priestly guardians began welding themselves into a very different Jewish sect in Babylon and, on returning from exile around 540 BCE, accelerated that process in reaction to what they termed the misrule of the newly entrenched Aaronic Temple priests.

Under the Persians the population was treated with respect. Religious life in Judah continued relatively uninterrupted whilst Aramaic became the predominant language, as opposed to paleo-Hebrew. However, something happened soon after the end of the fourth century that frightened the guardian Levite priests into seeking a safe refuge. That something was the prospect of once again being ruled by ‘pagan’ Egypt8, and by the second century BCE a leader arose, a Teacher of Righteousness, who would crystallise their beliefs.

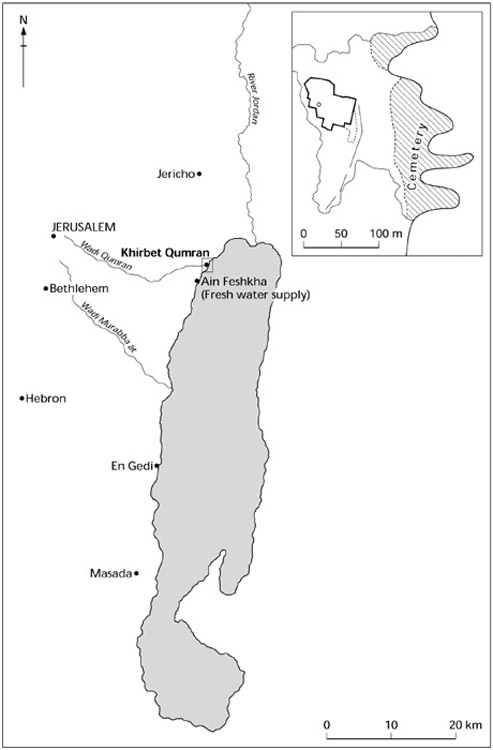

The priestly guardians scoured around for a place of refuge. Like their ancient predecessors, they looked for a secretive place that was near to water, to enable them to perform the purification rites that were part of their code. The choice was limited. There was, nevertheless, a honeycomb complex of caves on the shores of the Dead Sea that would serve their purpose well for the next 250 years – Qumran.

Although the Dead Sea was too salty to provide potable water, they chose a place where there was a spring, some 4km south of Khirbet Qumran. Here they worshipped, scribed, studied and died.

A MODERN VIEWPOINT/SECOND OPINION

I have discussed the basic theory connecting Akhenaten’s ‘new religion’ to that of the Qumran-Essenes with Professor George Brooke, Co-Director of the Manchester–Sheffield Centre for Dead Sea Scrolls Research, and a world renowned authority on the subject.*36 He has recently been appointed editor for a new series of books entitled The Dead Sea Scrolls (being published by Rout-ledge) and organized a recent exhibition of the Copper Scroll at Manchester Museum, from October 1997 to January 1998.

Professor Brooke goes along with the general idea that Egyptian influences could well have penetrated into the philosophy of the Qumran-Essenes and comments ‘Egypt would have been a place where a Jewish association would feel comfortable and its religious environment would be consistent with monotheistic traditions.’ However, he proposes another route by which the influences might have travelled.

The alternative theory he suggests is that the knowledge the Qumran-Essenes might have acquired about the monotheism of Akhenaten, and Egyptian religion in general, may well have been imbibed at a later date, namely in the sixth century BCE, possibly through the associations Ezekiel and Jeremiah had with Egypt.

As outcasts from Temple life and privilege after the destruction of the First Temple, the priestly group that was eventually to evolve into the Essenes, disillusioned by the failure of God to protect their holiest place, may well have been looking for an alternative form of Judaism to sustain them in their relative isolation, a form that might distinguish them from the mainstream body of Jewish religion.

There was undoubtedly considerable contact between Judaean Judaism and the settlements of Jews who were dispersed to Egypt after the destruction of the First Temple. (Most of the dispersions were to Babylon and to parts of the Babylonian Empire east of Jerusalem. But several thousand captive Jews were taken to the northern Nile delta region of Egypt.)

Professor Brooke maintains that, if my theory that a residual strand of Akhenaten’s monotheism survived within a group of priests in Israel is correct, what would be more natural than that they, as a proscribed group of Jewish priestly thinkers, might find sympathetic understanding with another ostracized Egyptian group with similar monotheistic beliefs? Contact between Jews dispersed to Egypt and those remaining in Israel after the destruction of the First Temple is known to have taken place after 550 BCE. There could well have occurred, therefore, an interchange of information, bringing the ideas of Akhenatenism and some of its secrets to this Jewish sect. Professor Brooke notes that:

At its outset the Essene movement was predominantly priestly and is evidence of a priestly pluralism in the three centuries before the fall of the Temple in 70 CE. The Jewish priesthood in Egypt was clearly revitalised at the time of Onias IV by his move to Heliopolis in the second quarter of the second century BCE,9 the very time at which the Essene movement was being established in Judaea.10

Whilst my view remains that the Essenes (and, subsequently, the Qumran-Essenes) gained their knowledge of Akhenatenism through a direct connection to the Akhenaten period, rather than through Professor Brooke’s later and indirect linkage, the net outcome does not alter the essence of the Egyptian influences that I have proposed. However, it would have an impact on how the Qumran-Essenes acquired the knowledge contained in the Copper Scroll.

I also discussed some of my theories with Jozef Milik (see Plate 10(top)), the man who led and organized the original Dead Sea Scrolls translation team working on scroll fragments at the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem. Born in the village of Serwczyn, Poland, eighty-one years ago, he was educated at the University of Lublin and came to Jerusalem from the Biblical Oriental Institute at Rome as a Catholic priest at the end of 1952. He was the doyen of Qumran scroll research, the first person to produce an official translation of the Copper Scroll, and he has dedicated his life to the study of ancient Middle Eastern texts. When I met him in the autumn of 1998 at his Paris home, it was with some degree of awe that I talked with him about my theories and ideas. Although his eyesight is now poor, his mind is still razor sharp and on several occasions he corrected me when I mixed up a name or was unsure about a reference.

When I asked him if he still considered the Copper Scroll to be a fraud, he replied without hesitation, ‘No, no, no it is absolutely excluded…it was found under metres and metres of earth…it was found with small fragments of manuscripts of the library.’ However, he still considers that the contents of the scroll ‘do not correspond to reality’ – to be based on legend – and he referred to similar lists of treasure found in Egypt. Why the document was written ‘was a problem’.

Jozef Milik agreed that the numbering system in the Copper Scroll could have come from Egypt and could date back to the time of Akhenaten but found it difficult to make a connection right back from Qumran to Akhetaten equating the jump as equivalent to the claim of the Freemasons that they can trace their origins back to Solomon’s time. When we came to discuss the Copper Scroll translations in detail, he did not find it easy to accept my reasoning for the connections I proposed. However, he was far from dismissive, asking probing questions and acknowledging with surprise that some of the evidence appeared convincing, and yet puzzling. He agreed that there was a lot of concordance between Egypt and the Jewish nation but suggested the Therapeutae as a possible link between Egypt and the Essenes.11

(Currently Monsieur Milik is working on the decipherment of a bilingual inscription found on a second century BCE temple in southern Syria. The inscription describes four gods who were worshipped there – Ben Shammen, Isis, a local goddess Shiyiah and the Angel of God – Malach el Aha.)

AKHENATEN’S HEIRS

If my assumptions – that the Essenes of Qumran were the heirs of the priestly guardians of the Covenant and can be traced back to the priests of Akhetaten – are correct, then we would expect to see many ‘fingerprints’ in their activities and writings to mark them out from the general Jewish population.

These expected fingerprints would include:

- a different version or conception of the generally accepted Torah teachings and a closer relationship with the religion of Akhenaten

- a sense of guardianship and divine mission

- emphasis on the sun – brightness – light

- extreme ritualistic cleanliness

- stronger Egyptian influences.

We might also expect some memory of the original holy city of Akhetaten. The catastrophic destruction of the Temple there would have inevitably left a deep scar on their subconscious. Perhaps, in the extreme, there might also remain some knowledge of the whereabouts of the treasures buried at Akhetaten, or the treasures that Moses and the priests brought out of Egypt.

It would in itself be quite surprising if any of these listed characteristics were found amongst the Essenes – especially that of Egyptian influences – after so long a period of immersion in a foreign culture and a refined Judaism that had ‘cleansed itself’ of as many foreign influences as possible. One would certainly not expect to see more Egyptian influence within a closed sect than was apparent in the common body of Judaism. But we do. In fact, we find the Essenes exhibited many of the characteristics of the priests that came out of Egypt, modified by time in just the form that one might expect.

There are not just ‘fingerprints’ of the connection between Akhenaten and the Qumran-Essenes, there are ‘smoking guns’!

Before going into the ‘religious fingerprints’, I have uncovered some intriguing visual and pictorial links to Egypt and the City of Akhetaten, which are quite surprising.

ORIENTATIONS AT QUMRAN

The following very strange coincidences give us visual links between the Qumran-Essenes and Akhenaten. So strange are these links that I do not think they are mere accidents of chance. I believe they constitute a body of evidence that, on its own, clinches the connection between the Qumran-Essenes and Pharaoh Akhenaten. Before reading the next paragraph, turn to the plate section of illustrations and look closely at Plate 10 (bottom) – the hills above the Qumran settlement. What can you see?

When I first noticed the images, I thought I was dreaming. The photograph was printed in a book entitled The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered, by Robert Eisenman and Michael Wise, first published in 1992. No-one previously seems to have noticed what I hope you have seen for yourself. Amongst the Mount Rushmore-like shapes in the hills directly above Qumran there appear to be faces. For me, these elongated faces look remarkably like ancient Egyptians. If that is what they are, what on earth are they doing staring out over the ruins of a Jewish settlement on the Dead Sea? There are only three reasonable explanations. They were carved, possibly by members of the Essene community; they are the result of weathering and are quite accidental; or they are the work of the hand of God. On closer examination I believe the faces are the result of weathering, but nevertheless their existence is quite unnerving!

The ‘orientation’ story now shifts back to the Congress held in Jerusalem in July 1997, to celebrate the fiftieth year of the finding of the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Some 300 delegates, including experts from all over the world, gathered in the magnificent setting of the Israel Museum grounds where the Shrine of the Book is located, to indulge in an academic freudenfest of learned exchanges.

One of the papers presented at the Congress was given by Joerg Frey, an academic from Tübingen, Germany.12 His specialism was the so-called ‘New Jerusalem’ text, which comprises six manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Written mainly in Aramaic, they are considered by most scholars to relate to the description of an idealized city that might exist in an eschatalogical period at the end of time and are identified with the visionary writings of Ezekiel 40–48 (and to Revelations 21).

However, there are serious problems with this identification. The texts (which do not actually mention the word ‘Jerusalem’) describe a much larger city than Ezekiel’s and cannot be easily related to a plan of Jerusalem at any time in its history. As Herr Frey put it, the plan of the ‘New Jerusalem’ in the Dead Sea Scrolls is difficult to understand and it is unclear from where the people who wrote these particular Qumran-Essene documents got their ideas. A clue was not long in coming.

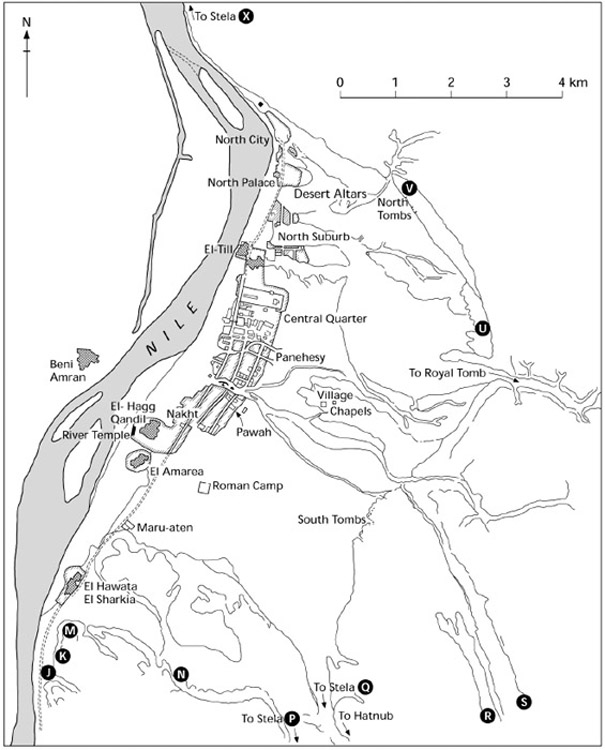

My ears pricked up when a delegate in the audience commented during question time that a number of researchers, including Shlomo Margalit, Georg Klostermann and Ulrich Luz, had studied the ‘New Jerusalem’ texts in the 1980s.13 They had compared the city plan descriptions in the texts with actual cities in the ancient Near East and had come up with a ‘best fit’ of…Akhetaten! The same Akhetaten that was Pharaoh Akhenaten’s holy city on the Nile, situated in lower Egypt, now know as El-Amarna.

If this assertion was correct, what clearer evidence could there be that the Qumran-Essenes knew the plan of a city that existed 1,100 years before their time? A city that had been made desolate very soon after the death of Akhenaten in 1332 BCE, resettled in Romano-Ptolomaic times and then long-since abandoned and forgotten.

I decided to look at translations of the original ‘New Jerusalem’ texts myself and to make my own comparisons.

Text 5Q15 of the ‘New Jerusalem’ texts, found in Cave 5 at Qumran, reads as follows:

[round] = 357 cubits to each side. A passage surrounds the block of houses, a street gallery, three reeds = 21 cubits (wide). [He] then [showed me the di]mensions of [all] the blo[cks of houses. Between each block there is a street], six reeds = 42 cubits wide. And the width of the avenues running from east to west; two of them are ten reeds = 70 cubits wide. And the third, that to the [lef]t (i.e. north) of the temple, measures 18 reeds = 126 cubits in width. And the wid[th of the streets] running from south [to north: t]wo of [them] have nine reeds and four cubits = 67 cubits, each street. [And the] mid[dle street passing through the mid]dle of the city, its [width measures] thirt[een] ree[ds] and one cubit = 92 cubits. And all [the streets of the city] are paved with white stone…marble and jasper.14

The Dead Sea Scroll texts conceive the city as covering an area of 25–28km2, an area very similar to that of the city of Akhetaten, as revealed through excavations.15 The style and formula of presenting measurements is also quite similar to that used at the time of the city’s existence, exemplified in an inscription on a boundary stela, stela ‘S’, found at El-Amarna, which describes the dimensions of the Akhetaten site.16

Excavations at El-Amarna by Sir Flinders Petrie,17 Professor Geoffey Martin18 and, more recently, by Barry Kemp of the Egypt Exploration Society, show that Akhetaten had three main streets running east/west, and three running north/south, almost exactly as described in the Dead Sea Scroll texts. The streets were unusually wide for an ancient city, being between 30m and 47m in width, again closely corresponding to measurements in the ‘New Jerusalem’ texts, as do the distances between the blocks of houses.

The descriptions of streets ‘paved with white stone…marble and jasper’ are especially noteworthy. Akhetaten was the ‘beautiful gleaming white city’ of Egypt. Built on virgin land in a vast sandy plain that formed a natural hill-surrounded amphitheatre on the banks of the Nile, no expense had been spared in its construction. Roads, pavements and buildings were made of the finest available materials. An exquisite example of the craftsmanship that was lavished on the city can be seen in the painted pavings that adorned Akhetaten’s main palace, reconstructed in the Cairo Museum. A glowingly beautiful piece showing a blue, green, yellow and red marshland setting for a duck-like bird can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

By all accounts the city must have gleamed white in the sunlight, its roads and buildings made from limestone, which had the appearance of alabaster.19

The ‘Jerusalem text’ goes on to describe the dimensions of a huge building, and various houses in the city. A comparison of the archaeological reports of the Great Temple at Akhetaten indicates that this is the building the texts are describing.

A recent comprehensive study of the New Jerusalem Scroll, by Michael Chyutin, also concludes that the city plan of Akhetaten appeared to form a template for the Qumran-Essenes’s idealized vision of their Holy City.20 However, the author can only speculate on the reason for the association: ‘Why did the author of the Scroll describe a city planned in an archaic Egyptian style, rather than describing a Greek city or a Roman castrum?’

The work by Shlomo Margalit and his colleagues, by Michael Chyutin, and my own cross-checking can leave little doubt that the Qumran-Essenes had in their possession works handed down from previous guardians of their literature, which must have been composed within living memory of 1300 BCE (the date the city of Akhetaten is thought to have been destroyed by Pharaoh Haremhab).21 They knew exact details about the geographical layout of Akhetaten, details that appear in no other source.

If the Qumran-Essenes knew the layout of what I believe they considered as their model ‘holy city’, did they make use of that knowledge in other ways? Was there a connection to the Copper Scroll? Clearly the knowledge of the city layout would have been useful to them in visualizing the whereabouts of some of the treasures described in the Copper Scroll. The city plan was, after all, a reference grid for the description of where some of the treasures were hidden. But there is more.

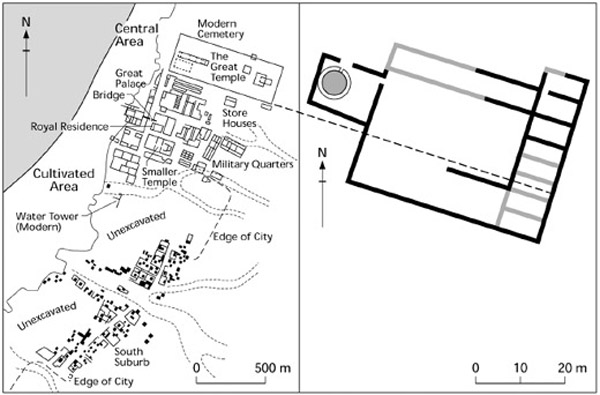

If, as I surmise, the Qumran-Essenes knew the direction and layout of their ‘holy city’, wouldn’t they have made use of that knowledge when they came to build their own ‘holy settlement’? It would be surprising if it had not had some influence on their constructions. The initial site correspondences were there – a flat area, near to water, backed by hills.

Look at Figure 14 on page 152. The geographical alignment of the Qumran settlement is approximately north-west. If we overlay the reconstructed outline plan of the Great Temple at Akhetaten on the outline plan of the settlement at the Qumran site, we find the walls of both buildings are in exact geographical alignment. The main walls of both buildings are parallel. This is weird. The fit is so precise, it cannot be a matter of chance. Almost as incredible is how did the Qumran builders achieve this accuracy in alignment over such a vast distance, even if they had wanted to? Whether some solar, stellar or other comparator was employed must remain the subject of another study.

Figure 13: Site of Akhetaten showing outline plan of streets and buildings.

As I have shown before, relating numbers, size and alignment was an important preoccupation and skill of ancient civilizations, particularly for the Egyptians, but how the Essenes managed to achieve such an accuracy in this instance is a mystery.

Figure 14: Overlay of the Great Temple at Akhetaten on the plan of Essene buildings at Qumran showing the parallel orientation.

Orientation for Egyptians was vitally important. Buildings were not just put up randomly. They were positioned with extreme precision in relation to other constructions and natural heavenly bodies. Dimensions and angles of the actual construction were also carefully programmed. For these reasons when a concurrence of angles, dimensions or alignments is discovered it is immensely significant. The alignment of an aperture or shaft in a building so that sun or starlight could illuminate a desired position at some precise required time is repeated in many settings. A couple of examples will illustrate the point.

Mark Vidler’s book, The Star Mirror, shows that the builders of the Great Pyramid at Giza were able to measure star angles to an accuracy of ‘one arc minute’, and used isosceles triangular alignments of pyramids on the Giza plateau to mirror isosceles triangular configurations of stars, to highlight special dates in the calendar.22

Another example relates to the Great Temple built by Ramses II at Abu Simbel, in southern Egypt. It was deliberately built in such a way that twice a year, on the 22 February (the date of his birthday) and on the 22 October (the date of his coronation), the sun shines directly over the holy shrine, illuminating the Pharaoh’s throne.23

The ‘singing statue’ is our last example. Two huge statues of Akhenaten’s father Amenhotep III can still be seen in front of the Valley of the Kings, on the west bank at Thebes. When Strabo, the Greek first century BCE writer, visited the site, he recorded that every morning when the first rays of the sun struck one of the statues, it let out an audible singing note, which he was at a loss to explain.24

The Qumran Cemetery

In May 1998 Dr Timothy Lim, Associate Director of the Centre for the Study of Christian Origins at the University of Edinburgh, organized an international conference on ‘The Dead Sea Scrolls in their Historical Context’. The conference was held in the architecturally grandiose Faculty of Divinity building, adjacent to the old Assembly Hall of Edinburgh (where the new Scottish Parliament will hold its initial meetings).25

The first presentation was given by Professor E. P. Sanders, of Duke University in America, and during the discussion the question came up of why all the bodies of the Essenes in the graveyard at Qumran were buried with their heads facing south.

The large main cemetery at Qumran faces east and is some 50m from the site of the settlement, in between the settlement and the Dead Sea. Some 1,100 graves have so far been identified. They are arranged in neat, close-ordered rows, contrasting to the usual disorder of cemeteries in ancient Palestine. The graves are simple dug-out trenches marked by a small pile of loose stones. To date about fifty-five graves have been excavated, and from the random choice of excavation, it is statistically certain that all the bodies in the main cemetery are male. Female and children’s bones were found in secondary cemeteries. All the human remains were buried naked, without adornments and with no worldly goods, apart from a few examples of ink pots and a mattock. The bodies were all buried lying on their backs, with their heads turned carefully in their graves to face south.26

Neither Professor Sanders nor anyone in the audience had an explanation for this peculiarity. Jerusalem, the natural direction to face, was, after all, to the west. Absorbed in the repartee of the discussion I literally had to bite my lip to stop myself gushing forth with my own explanation: ‘South was the direction of the Qumran-Essenes’ “holy city” of Akhetaten!’

Figure 15: Map showing the location of Qumran, and an enlarged view (inset ) of the site remains and cemetery.

As we have seen from the ‘New Jerusalem’ Scroll, not only did the Qumran-Essenes know where Akhetaten was, a city destroyed 1,000 years before their time and long expunged from Egyptian memory, they had detailed knowledge of its layout.

The form of burial – naked and without any worldly accoutrements – practised by the Qumran-Essenes is quite consistent with the simple style introduced by Akhenaten, who swept away all the accompanying ‘furniture for the afterlife’ and burial cults associated with tombs prior and subsequent to his reign. Akhenaten, like the Qumran-Essenes, did not believe in a physical resurrection of the body, but in a spiritual re-emergence in the next world: the Qumran-Essenes believed that they would be received into the ‘company of angels’ after death.27

The Essenean asceticism associated with burial was in sharp contrast to the general behaviour and attitude of the Jewish populace in Judaea and elsewhere, which had ‘slipped back’ into a cult-type reverence for the dead. For them it was a sojourn in the darkness of the underworld, and it became customary to provide:

- food for the journey

- sprinkled water on the grave to provide refreshment

- weapons for men, and ornaments for women to help them in the after-life

- tombstones with names

- protective amulets.

None of these practices or beliefs were held to by the Qumran-Essenes. All of them, however, can be identified with pre- or post-Akhenaten Egyptian practice and belief.

The Qumran-Essenes’ belief was in sharp contrast to the Pharisaic belief of bodily resurrection,28 a belief that prevailed amongst the general population after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and predominates in Orthodox Jewry to this day. (Interestingly, the Reform and other Progressive movements of Judaism have, over the last one hundred years, moved back towards the original doctrines of the Qumran-Essenes. They have progressively reduced their acceptance of bodily resurrection and now advocate belief in an ongoing spiritual soul after death.)

What then of the Copper Scroll – the penultimate expected ‘fingerprint’ – and the treasures of the First Temple (or perhaps an even earlier Temple)? If there had been little advanced recognition that the Temple was in danger, the chances of hiding away all the sacred articles would have been reduced. Considering the timescale of advanced warning, from prophets like Jeremiah, there would appear to have been time for the ‘priestly guardians’ to have hidden some of the treasures of the Temple, and to have written down where they were hidden – perhaps to add these locations to a list of treasures they already knew about from another Temple – before the cataclysmic event that shattered Jewish history and brought the Southern Kingdom to an end.*37

Many of the scrolls in the possession of the Qumran-Essenes were secretive documents, unknown to the outside world. Like their attitudes towards death and burial, many of the scrolls of the Qumran Community relate to beliefs and activities that were inconsistent with the normative Judaism of the time. These inconsistencies have not been explained satisfactorily, in fact very little attempt has been made to explain them at all. Tracing their underlying meaning back to the time of Akhenaten explains most of the anomalies, and the solution to the enigma of the Copper Scroll.

The search for these answers, in the engraved letters of a treasure map, encrypted in the form of a Copper Scroll, is about to enter its final exciting stage.