THE LOST TREASURES OF AKHENATEN

Prepare for the exciting climax of an extraordinary treasure hunt – a denouement that will irrefutably underscore the contention that the Qumran-Essenes were the direct executors of Akhenaten, with all that that implies about the undoubted influence they had on Christianity and Islam.

Prepare for the exciting climax of an extraordinary treasure hunt – a denouement that will irrefutably underscore the contention that the Qumran-Essenes were the direct executors of Akhenaten, with all that that implies about the undoubted influence they had on Christianity and Islam.

In John Allegro’s original analysis of the Copper Scroll, he identified four likely locations for the lost treasures listed by the Qumran-Essenes. Namely, in the vicinities of:

- The Dead Sea

- Jericho

- Jerusalem

- Mount Gerizim*38

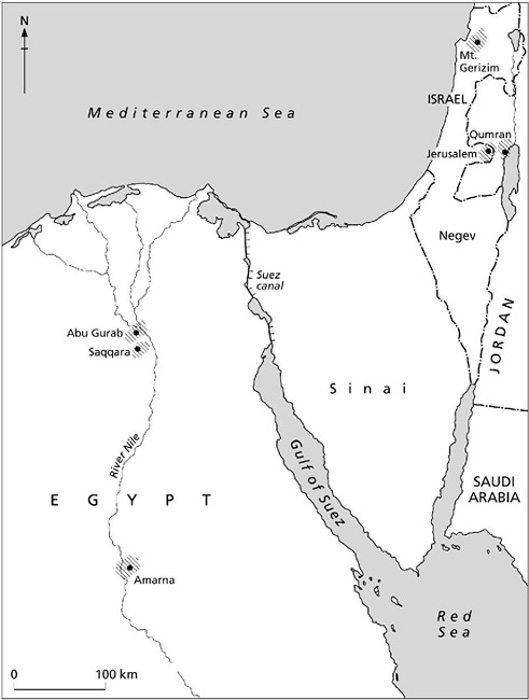

Quite specific depositories of the treasure are pinpointed by John Allegro within the ruins of the Qumran-Essene monastery at Khirbet Qumran; near Ain Farah; in the Antonia fortress at Haram; at Wilson’s Arch in Haram; at tombs in the Kidron Valley; on the Mount of Olives and Mount Gerizim and in Jerusalem.1

Many of the locations mentioned appear to refer to Jerusalem, or its close vicinity. Since it would not be wise to go digging at the Temple site – for fear of attracting a hail of machine-gun fire as official permission is difficult to obtain – for reasons of religious sensitivity, I will concentrate on locations that can possibly be explored and excavated. The same considerations apply to what are now largely built-up areas of Jerusalem. Although locations in Jerusalem are difficult to excavate, over a period of forty-five years none of the suggested locations has yielded any treasures.

From the deductions that I have made and the conclusions reached earlier in this book, there are sufficient clues to identify additional candidate sites where parts of the treasures mentioned in the Copper Scroll may be found. Careful study of these sites will assist anyone determined enough to venture forth with spade, metal detector and the necessary permits.

The sites are within nearby proximity, or easy access, to:

- El-Amarna – ancient Akhetaten – in northern Egypt

- Faiyum, Hawara and the Delta regions of northern Egypt

- Elephantine Island in southern Egypt, and Heliopolis near Cairo.

- Lake Tana, in Ethiopia

- The First Temple at Jerusalem

- The Caves of Qumran on the Dead Sea

- Mount Gerizim in northern Israel

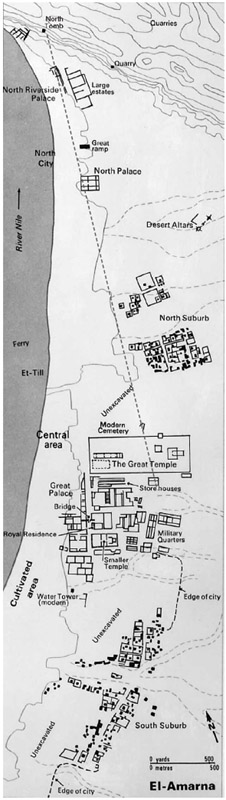

You may find it useful to refer back to Figure 1, the relational map of the area, as I discuss the individual sites.

El-Amarna

With the sudden demise of Akhenaten, at a relatively young middle-age, the rule of the Kingdom fell to Tutankahmun, his brother (and husband of his daughter), who was still a child, following a brief interlude by the enigmatic Smenkhkare. Neither of these two pharaohs had the political strength to resist the machinations of the priests of Thebes, who may have started to move against Akhenaten’s power bases as soon as they heard of his imminent death.

The time to squirrel away the treasures of the Great Temple, Palace, and Treasury of Akhetaten may therefore not have been too long. The sheer weights and volumes involved could have amounted to several tonnes of precious metals and valuables. The work could not be entrusted to labourers – unless they were to be killed subsequently – so the hard graft had to be done by the caucus of priests. It would also seem inevitable that, with such a volume of treasure, it would not have all been hidden in one location but would have been spread around to increase the chances of some of it remaining undetected.

The greater the weight of treasures to be hidden, the less the likely distance of travel from the source. The most probable areas, therefore, are in the immediate vicinity of the Great Temple..

Stretching half a kilometre to the north and south of the Temple complex before the North and South City suburbs would have been reached, there are two unexcavated areas of land. These are possible sites for treasure burials but are relatively unlikely in view of the proximity of workmen’s villages and the danger of spying eyes.

However, going south of the present day village of El-Till, and following the track beside the edge of the cultivated land, we are walking along what would have been the main street of Akhetaten. Where the city’s main administrative centre would have been is now marked by two mudbrick pylons – all that remains of a bridge that connected the ‘King’s House’, to the east, with the Official Palace, to the west. This enormous complex of buildings has never been fully excavated and contains numerous inexplicable features. Here, under cover of darkness, many of the treasures of the Palace and King’s residence could have been secreted.

Figure 16: Site of Akhetaten showing view of Great Temple, stelae and tombs.

A most promising location for the treasures of the Temple lies in the vicinity of the Tomb of Akhenaten and the southern group of private tombs. Already prepared for him during his lifetime, it would have been a natural place for the priests to consider.2 It lies a suitably safe and secluded 12km east of Amarna, along the ‘Royal Wadi’ (today, inaccessible to motor vehicles).

The private tombs, many with sand-blocked entrances, face the village of Hagg Qandil and the public are not allowed access. This, however, is a likely place where some of the treasure of the Temple of Akhenaten may be found.

Faiyum and the Delta Region

Another compelling location for some of Akhenaten’s treasure to have been hidden lies some distance from Amarna, at the place where Joseph’s family were settled. It is the Faiyum area, adjacent to the outfall of the Bahr (River) Jusuf, at Lake Qarun.

During Joseph’s lifetime, Lake Moeris, as it was then known, would have been far more extensive, and I looked for an area that might have contained extensive ruined buildings and temples – hidden labyrinths. Taking the Hawara road you arrive at Medinet El-Faiyum.3 A secondary road runs northwest to Kiman Fares, once known as Crocodilopolis, where you come across an extensive area of town ruins, which stretch over four square kilometres. Here the Hebrews may have been set to work by Ramses II to rebuild temples dating back to the Middle Kingdom period, and shrines for the worship of the sacred crocodiles.

A Biblical reference, in Genesis 47:11, indicates that the Hebrews were associated with the Delta region of the Nile:

And Joseph placed his father and his brethren, and gave them a possession in the land of Egypt, in the best of the land, in the land of Ramses, as Pharaoh had commanded.

I suggested earlier (in Chapter 10) that the Faiyum region, rather than the Delta region, was where the Hebrews were originally settled. However, the Biblical references to Ramses and Pithom (previously Avaris and Tanis) indicate that the Hebrews were also set to work by Ramses II to build storehouses for him at these sites. So it is conceivable that these places of storage could have been sites from where Moses gathered some of his people for the Exodus, and at the same time secreted the details of the treasures that could not be carried with them from Egypt.

Elephantine and Heliopolis

After the priests of Akhenaten fled the destruction of Akhetaten, I suggested that some of them settled at the Island of Elephantine and at Heliopolis, so both these areas warrant re-evaluation and excavation.

Archaeological evidence shows, as we have previously noted, that there was a pseudo-Judaic militaristic community at Elephantine on the extreme southern borders of Egypt, at least as early as the seventh century BCE.4 The relatively ‘certain’ early date shows that they were not ‘Dispersees’ (Diaspora) from the fall of the First Temple in 586 BCE but had arrived from somewhere other than Israel. Justification for this assertion needs a fuller discussion and I will go into more detail later in Chapter 19.

Lake Tana

When the Community at Elephantine suddenly disappeared in 410 BCE, it is not unfeasible that the survivors journeyed deep into Ethiopian territory and eventually settled on the shores of Lake Tana in the northern part of the country. Like the Judaic Community of Elephantine, the Community of Lake Tana, now known as Falashas, had, and still have, unusual customs and practices, reflecting a people who had not participated in the mainstream Judaism of Canaan. Like the Essenes they did not keep Purim*39 or the ceremonies related to the Dedication of the Temple.

It is possible that the ancestors of the Falashas took away to Ethiopia some residual treasures, but their location would and could not have been recorded in the Copper Scroll of the Essenes.

The First Temple at Jerusalem

The impending threat of the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians in the years before 586 BCE must have wrought untold anxiety on the population. As guardians of the Holy incunabula and treasures that came out of Egypt, the priests of the Temple would certainly have taken the opportunity to carry many of the sacred and valuable items to hiding places in or near Jerusalem.

When Nebuchadnezzar’s iron fist finally reached Jerusalem, those treasures that were not saved were carried off by the Babylonians as spoils of war and are lost to the mists of time.

Whilst it has not been possible to excavate fully at the site where the Temple is thought to have stood because the Dome of the Rock and Muslim Temple of Al Ahxsa now occupy a large area of the Holy Mound, it is unlikely that any holy relics or treasure described in the Copper Scroll would be found there.

The Caves at Qumran

Many textural treasures have already come out of the finestriated hills of Qumran since the accidental finding of the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1947. There may be more ‘textual’ treasures to be discovered, but the area has been explored so intensively that the likelihood of large amounts of treasure being found becomes increasingly remote.

CRACKING THE CODE OF THE COPPER SCROLL

At this stage in my researches I went back to the original source – to the Copper Scroll itself – to reconsider the mixture of Egyptian and ancient Hebrew exhibited in it. I came to the intriguing possibility that the Copper Scroll refers to both Israeli and Egyptian locations. Having isolated the most likely general areas for the treasures of Akhenaten to be found, I started to home in on more exact locations, with the help of the Copper Scroll.

Going back to the scroll, I needed to address a number of questions before I could make more progress:

- Does the scroll contain some kind of code that, once solved, will lead to the treasures it describes?

- Were the Qumran-Essenes prone to writing in code?

- If so, are any other Dead Sea Scrolls written in code?

The answer to all these questions proved to be ‘yes’.

When referring to their own Community, the Qumran-Essenes often used cryptic codes, mirror writing and hidden messages within their own texts.

Looking at several examples of other Dead Sea Scrolls, it became immediately obvious that the Qumran-Essenes, indeed, had a fondness for codes, and this predilection gave me an insight into the quirky minds of these hermit-like people. More importantly, it unambiguously showed the scribes to be familiar with Egyptian symbols in use between 1500 and 1200 BCE, a period comfortably encompassing the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

One example is Scroll 4Q186 (dealing with horoscopes), which includes Greek, square-form Hebrew and Paleo-Hebrew letters encrypted as mirror writing.

Another scroll, known as the ‘Admonitions of the Sons of Dawn’, was found in Cave 4 at Qumran. This scroll is different from other scrolls. It begins in Hebrew, with a mention of the ‘Maskil’ (‘Teacher’), and then converts to apparently arbitrary cryptic symbols, plus a void character that is quite unknown in the Hebrew alphabet!

Robert Eisenman and Michael Wise5 deciphered the text of the ‘Admonitions’ scroll by equating what appeared to them to be ‘twenty-three more or less arbitrary symbols’ with Hebrew letter equivalents. When I looked closely at the apparently random cryptic symbols, it became clear that they are mainly Egyptian in origin. Many of the symbols are based on hieroglyphics or hieratic writing – a cursive form of hieroglyphics used by Egyptian priests. For example, the symbol used for the Hebrew ‘aleph’ is part of the sound ‘meni’ made from the hieroglyphic sign

turned through 90º. The symbol for the Hebrew letter ‘shin’ is the Egyptian hieroglyph for a ‘wall’. The symbol below – the Hebrew letter ‘zahde’ – is the Egyptian ‘ankh’ sign for ‘life’.

turned through 90º. The symbol for the Hebrew letter ‘shin’ is the Egyptian hieroglyph for a ‘wall’. The symbol below – the Hebrew letter ‘zahde’ – is the Egyptian ‘ankh’ sign for ‘life’.

Why would the Qumran-Essenes still utilize an ancient form of Egyptian writing, closely related to the writing that Moses must have used in recording the early Old Testament texts? The answer can only be that ancient Egyptian writing was still important to them, and part of their inheritance.6

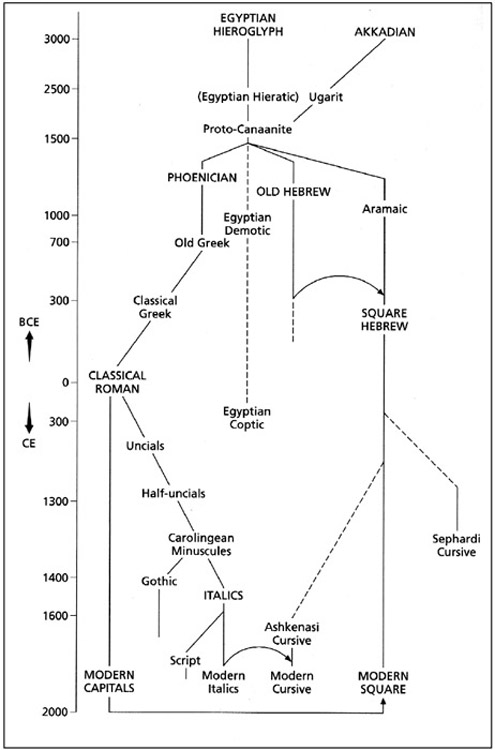

An outline of the types of language and writing, in use in the Middle East from earliest times up to the period when the Dead Sea Scrolls were written will be helpful in assessing the types of writing that were available to the Qumran-Essenes.

These examples of the use of codes by the Qumran-Essenes made me fairly confident that the interspersion of Greek upper case letters in the Copper Scroll, which do not have an immediately obvious meaning, indicated that this Scroll falls into the category of having a hidden meaning. I was already suspicious of the numbering system used in the scroll, as it is not equatable with the Hebrew format in use at the time of its engraving around the time of Jesus but is identifiable with much earlier dates. The treasure weight dimensions (see Chapter 2) are also clearly exaggerations if taken as Hebrew weights. It would therefore be naive to take the locations and related numbers, as described in the Copper Scroll, at face value.

As Greek-language influences in Judaea did not appear until after 250 BCE, it is safe to conclude that the Copper Scroll was not engraved until after this date. Its rough-and-ready writing indicates that it was a copy of an earlier document done with some haste. It is written in a form of Hebrew unlike that used in any of the other Dead Sea Scrolls, with previously unknown word forms and numerous mistakes by the copyist. I believe that part of the scroll was copied from an original document written in Egyptian hieratic.

Table 4: Forms of Writing and Language in the Ancient Middle East

| EGYPT | |

| Hieroglyphs | Pictorial symbols from 2nd Dynasty onwards (3000 BCE) |

| Hieratic | Cursive writing form of hieroglyphs, mainly used by priests from 11th Dynasty onwards (2500 BCE) |

| Demotic (Enchorial) | Business and social form of Hieratic from 900 BCE–300 CE |

| Greek | From 330 BCE onwards7 |

| Coptic | Egyptian language written in Greek letters 200 BCE onwards |

| MESOPOTAMIA | |

| Cuneiform | Pictorial symbols pre-1800 BCE |

| Akkadian | Semitic language, also in international use from 1500 BCE onwards |

| Aramaic, Ancient | North Semitic pre-1000 BCE |

| CANAAN | |

| Ugarit | 1500 BCE |

| Proto-Canaanite | |

| (Western Semitic) | 1400 BCE |

| Phoenician | |

| (form of Proto-Canaanite) | 1100 BCE |

| Paleo-Hebrew | c.800 BCE |

| Aramaic, Intermediate | c.600 BCE Semitic language Western Aramaic (language of the Palestinian Talmud) Eastern Aramaic (language (with Syriac) of the Babylonian Talmud) |

| Aramaic, International | Widespread use in and beyond the Middle East from 6th century BCE (language of the Elephantine papyri and parts of the Old Testament) |

| Hebrew (Square Form) | c.200 BCE |

| Greek | after 200 BCE |

| Latin | after 67 BCE |

THE TRANSLATIONS OF 3Q15 – THE COPPER SCROLL

This three- or even four-fold alloying of textual styles in the Copper Scroll has caused endless controversy over establishing a true meaning and syntax. But if 3Q15 is considered as an initial translation of a list that had been added to and amended and then copied again, many of the linguistic difficulties begin to fall away.

I believe the first translation and/or copying probably took place around 700–600 BCE or earlier, and the second copying around 40–60 CE. When the first translation took place, the scribe utilized the language of early paleo-Hebrew. With the second copying, amendments were incorporated to reflect the pre-Mishnaic interpretation (see Glossary), but much of the early Bible Hebrew wording was retained, as were the ancient Egyptian numbering and weighing systems. Running right through from the original hieratic document, into the ancient Hebrew and the pre-Mishnaic Hebrew mixture, are symbols and numbering systems that can be dated to well before 1200 BCE. Occasionally the scribe or revisionist could not resist tinkering with what must have been for him an antiquated method of numbering; for example, he changed the ‘khaff’ unit related to the weights to indicate it was a double ‘khaff’ or KK.

The numbering system in the scroll is inconsistent with first century CE Judaea. It is based on a single stroke for each individual unit with breaks of ten, with the smallest number to the left. It uses the same symbols and doubling of ten system used in Egypt at and before the time of Akhenaten. This system is identical to that found in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, now in the British Museum, which has been dated to c.1550 BCE8 (see Plate 3). Clearly the Copper Scroll has an allegiance to much earlier Egyptian times.

There is still no definitive translation of the scroll from the large numbers that exist, and so I have worked from four of the main versions that are most widely accepted by the majority of scholars as being of potential authority, adding my own interpretations where I diverge from all of their variants. The four translations I have worked from are by John Allegro, Garcia Martinez, Geza Vermes and Al Wolters.9 However, I shall endeavour to describe the main reasons for my selections as we go through the relevant parts of the text.

Each of the descriptions of the sixty-four treasure locations listed in the Copper Scroll are presented in the text in a similar pattern:

Figure 17: Schematic showing the development of writing forms.

a) a specific description of the hiding place

b) a secondary description of the hiding place

c) an instruction to dig or measure

d) the distance from a position by numbers of cubits

e) a description of the treasure

f) Greek letters (after seven of the locations).

A translation of Column 1 of the Copper Scroll text is typical of the style and content.

the ruin which is in the valley, pass under

the steps leading to the East

40 cubits (…) a chest of money and its total

the weight of 17 talents. KεN

In the sepulchral monument, in the third course:

one hundred gold ingots. In the great cistern of the courtyard

of the peri-style, in a hollow in the floor covered with sediment, in front of the upper opening: nine hundred talents.

In the hill of Kochlit, tithe-vessels of the lord of the peoples and sacred

vestments; total of the tithes and of the treasure; a seventh of the

second tithe made unclean. Its opening lies on the edges of the Northern

channel, six cubits in the direction of the cave of the ablutions, ΧÎ'Γ

In the plastered cistern Manos, going down to the left,

at a height of three cubits from the bottom: silver, forty

…talents…

The connections I have made back through the Qumran-Essenes to Ezekiel and Habakkuk, the Levites, the priests of On present in the Exodus, and to Akhenaten means that any interpretation should assume a strong ‘Egyptian Effect’ on the hidden meanings of the text. The numerical values are also all likely to be Egyptian in origin, rather than Canaanite.

A full translation, in the version given by John Allegro, of all twelve columns of the Copper Scroll, together with the ancient Hebrew text, is given in the Appendix.

THE FINAL HIDING PLACE

To begin at the end, as Lewis Carroll would recommend. The end of the last column of the Copper Scroll, Column 12, refers to a tunnel in Sechab, to the north of Kochlit. It is here, in this last mentioned place, that, we are told, is hidden the key to the Copper Scrolls:*40

In the tunnel which is in Sechab, to the North of Kochlit, which opens towards the North and has graves in its entrance: a copy of this text and its explanation and its measurements and the inventory of everything…item by item.

(My italics)

Clearly this confirms that the contents of the Copper Scroll cannot be taken at face value. There is a code, and a key that can unlock the code.

So where is Kochlit? What does the code mean? Where is the key?

In his translation of the Copper Scroll, John Allegro, one of the original editorial team who worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls, is very cautious (and rightly so) in assigning place-names to words that are essentially a grouping of consonants. By the nature of the Hebrew writing at the time, and as still pertains in the scrolls of the Torah, vowels were not included. Usually there is little ambiguity about the pronunciation and meaning of a word, but for unusual words, such as names and place-names, there is ample room for alternatives.

The Geza Vermes translation of ‘Kochlit’ is also given in the first, second, fourth and twelfth columns of the Scroll,10 but interestingly John Allegro here translates ‘Kochlit’ not as a place-name, but as

…and stored Seventh Year produce…

The ‘Seventh Year produce’, if it is a correct interpretation, is an unusual term. There is only one reference in the Bible that comes to mind for this kind of farsighted strategy. Could it be referring to the place where Joseph stored the last year’s and previous years’ excess gatherings of corn from the seven years of plenty for his Pharaoh, Akhenaten?

Do the Greek letters that appear in Column 1, which also contains the word ‘Kochlit’, have a bearing?

The Strange Greek Letters

No-one has previously come up with a satisfactory explanation of the meaning of the Greek letters in the Scroll, suggesting that they are indeed some kind of coded message, however many theories have been put forward. They are variously ascribed as referring to:

b) types of treasure

c) quantities of treasure

d) names of people

e) distances from locations

f) scribal marks

g) section divisions

One of the most recent authoritative translations of the Copper Scroll, The Copper Scroll, Overview, Text and Translation, by Al Wolters and published in 1996, refers to the Greek letters as follows:

Although various theories have been offered to explain the Greek letters, they remain an enigma. It may be significant that they could in each case be the beginning of a Greek proper name.9

Studying the Greek letters, and thinking about my theory that Moses, or the priests of Akhenaten who came out of Egypt with him, brought a ‘written map’ of treasures that remained hidden in Egypt, the solution to the Copper Scroll enigma suddenly dawned on me. A solution that was not inconsistent with Al Wolters’s suggestion.

My excitement at the discovery, as the letters fell into place, made the back of my neck tingle. The answer lies partly in the order of the locations described and partly in the cryptic Greek letters amended to some of the columns of text that have long mystified translators. They now began to have some meaning.

Later hiding places for the precious items that were brought out of Egypt and subsequently hidden in Canaan were added to the original texts being copied.

All the visible Greek coding marks occur in the first four columns of the Copper Scroll.

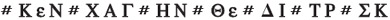

The letters are interspersed in the columns as:

The first ten letters spell (A)KHENATE!*41

I realized that I had cracked one of the most obstinate puzzles of the Copper Scrolls – one that has baffled scholars for decades.

The reaction of Jozef Milik to my explanation was one of wonderment. He was the first person to publish an official translation of the Copper Scroll and is an expert in ancient Middle Eastern linguistics. Whilst agreeing that the letters could relate to Akhenaten, he was puzzled as to ‘how the Essenes could know about the Pharaoh or his City’.11

In addition to Jozef Milik’s affirmation that the first ten Greek letters in the Copper Scroll might refer to Akhenaten or Akhetaten, I now needed to see if there were any references in classical literature that might use Greek letters to spell out these names.

Living in London, I was fortunate enough to be able to consult one of the most knowledgeable authorities on Egyptian and ancient Middle Eastern languages, Professor John Tait of University College London. He was kind enough to direct me towards a number of sources where I might find an answer.12

Gauthier’s Dictionnaire des Noms Geographiques gives the equivalent hieroglyphic sound of Akhenaten as: Ahk (on) t n – Åton, and from Calderini’s Dizionario dei Nomi Geografici e Topografici dell’ Egitto Greco-Romano the nearest equivalent name in Greek is ÅKAN ΘION

The fact that I could not find an exact Greek rendering of the name Akhenaten or Akhetaten was, as Professor Tait pointed out, not surprising as the Greek world would not have known of a place that had long since disappeared.13 Also, he added, there would not be Greek letters available to make the sounds equivalent to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic or hieratic words.

The nearest Greek letters that could have been used to represent pronunciations of Pharoah Akhenaten’s name, or its earlier version of Amenhotep, which the ancient Greeks were familiar with, was Amenophoris or Amenophis. Had they known of the Pharaoh’s later name, like the Qumran-Essenes, they might also have come up with the Greek letters:

Å Κ ε N Χ Î' Γ H N Θ ε

The meaning of the remaining Greek letters is discussed below, in their context within the book. The reason the Greek letters occur only in the earliest part of the Copper Scroll is, I believe, because the earlier columns relate to locations in Egypt and the scroll, being a form of list, has been added to at a later date with locations referring to Canaan.

The Seventh Year Storehouse

The meaning of the term ‘Kochlit’ as storehouse for the seventh year, as referred to in Column 1, now became clear. It is almost certainly one of the storehouses (probably the main one), next to the Great Temple of Akhenaten, where Joseph would have stored grain during the seven years of plenty in preparation for the seven years of famine. What more convenient place to hide the bulk of the treasures of the Pharaoh than at his capital Akhetaten, modern-day Amarna?

On the Upper Floor of the Museum at Luxor there are several statues of Akhenaten, and a breathtaking reconstruction of a wall from a Temple of Akhenaten at Thebes. Pictured on the talattat (blocks) of the wall are scenes of busy life on the Aten estates and, in one, a storehouse crammed full of pots, caskets, metal ingots and precious items. This is the kind of storehouse from which our search can truly begin.

If the reference in the final column, Column 12, does refer to the storehouse at Amarna, as the starting place from where a summary and explanation, item by item, will be found, (and if my theory is correct), I would anticipate finding Greek letters at the end of this passage also, to indicate it was an Egyptian location. There are none. However, this is almost certainly because there is a piece of text missing exactly where one would expect to find the Greek coding letters, with just enough space to accommodate two Greek letters. What those two Greek letters might have been, I will come back to shortly.

My theory is further endorsed by a reference to a place, in Column 4, that John Allegro reads as ‘the Vale of Achor’, and Garcia Martinez reads as ‘the valley of Akon’; I read as ‘the valley of Aton’.*42 From now on the pieces of the jigsaw fall neatly into place, each bit reinforcing the others.

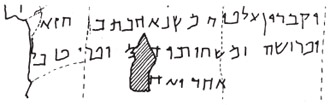

Figure 18: Illustration of text from the last column of the Copper Scroll.

The description at the end of the final column, therefore, refers to Egypt, and we start at the storehouses just south of the Great Temple.

…In the tunnel which is in Sechab, to the North of the Store House, and opens towards the North and has graves in its entrance: a copy of this text and its explanation and its measurements and the inventory of every thing [blank] item by item [missing piece].

Column 12

The Copper Scroll is saying: go due north of the stored seventh year produce and you will find a tomb or tombs.

Bearing almost exactly due north, as instructed, from the storehouses you do indeed arrive at a line of northern tombs, running along the edge of a quarry-ridden plateau just south of modern Sheikh Said. Here the plateau parallels the curve of the River Nile and comes right down to within about 30m of the river. What more convenient way to transport bulky treasure than by the river that is in close proximity to the Great Temple.

The tomb, which has a tunnel opening towards the North, has the key to the Copper Scroll buried in the mouth of the tunnel.

The ridge on which these Northern Tombs are situated faces in various directions following the contour of the hillside. Those of Meryra, Huya and Meryra II (or Kheshi as he has been called) face approximately south, and their tunnel openings run northward. All three persons were key officials in Akhenaten’s Court, and their tombs are candidates for determined further excavation.

As far as is known, Meryra was the only High Priest of Aten. His other titles were: ‘Bearer of the Fan on the right-hand side of the King’, ‘Royal Chancellor’, ‘Sole Companion’, ‘Sometime Prince’, and ‘Friend of the King’. He was also an hereditary prince and his tomb reflects his importance, with lavish decorated scenes of local life. About 60m behind his tomb at the top of the hill is a deep burial shaft, facing north. This location is a most likely contender for secreting the key to the Copper Scroll.

Reference in the translation of at Sechab as the location of the tunnel is another important clue. Looked at more closely, the Hebrew word could easily be translated as ‘Sechra’. There is one name that fits this pronunciation, and that is ‘Seeaakara’ – the mysterious King who immediately succeeded Akhenaten and is thought to have reigned as co-regent shortly before the Akhenaten’s death. Seeaakara, as King, is shown rewarding Meryra II, his scribe and superintendent, on an unfinished picture on the wall of the scribe’s tomb.14

The tomb of Meryra II, or, if it can be located, that of the mysterious Seeaakara (Smenkhkara), also warrants further intensive investigation.

Figure 19: Plan of the archaeological sites at Akhetaten, now known as El-Amarna.

BACK TO THE BEGINNING OF THE TEXT

Column 1

Returning to Column 1, the line ruin which is in the valley puts us, according to John Allegro, in the valley of the seventh year produce, looking for structures built before the time of Akhenaten, or which were then in ruins. There are steps leading east. The most likely contenders are the Desert Altars, not far from Akhenaten’s North Palace. These were enclosed in heavily buttressed brick walls, alluded to by John Allegro’s translation that describes the location as ‘fortress-like’. The altars, chapel and pavilion structure were either in ruins or dismantled in Akhenaten’s time. The Northern Altar can be approached by a ramp leading to the east. Forty cubits (or 20.4m) along this ramp and beneath it, there should be a chest of money with contents weighing seventeen Talents.

The next section refers to the sepulchral monument, where there are 100 light bars of gold. There is only one other reference to gold ingots, and that occurs in the ‘Egyptian’ Column 2. This talks about the carpeted house of Yeshu(?). I take this as meaning in the precincts of Akhetaten city. John Allegro, rather, reads this phrase as the Old House of Tribute. In one of the northern group of tombs there is a tomb of ‘Huya’, Steward to Queen Tiyi, mother of Akhenaten. The decorated chapel to Huya shows a scene of Akhenaten in the twelfth year of his reign, being borne on a carrying chair with his wife Queen Nefertiti to the Hall of Foreign Tribute. Below and to the side of the scene are pictures of visiting emissaries paying homage to Pharaoh. The ‘House of Tribute’ was almost certainly this Hall of Tribute of Akhetaten.

The Hall of Tribute was a large altar area forming part of the enclosure wall of the Great Temple to the north-east end of the building. It is quite likely that the floor would have been carpeted, for the comfort of the dignitaries who must have been constantly prostrating themselves at the feet of Pharaoh. In the cavity…in the third platform sixty-five gold ingots. Under the raised platform three levels down these gold bar riches must have been secreted.

Too late! Someone has got there first!

‘Crock of Gold Square’

In 1926 a team excavating the ancient city of Akhetaten had began a six-year season of work under its leaders, Dr H. Frankfort and J. D. S. Pendlebury.

The dig had reached the Central Western Quarter of Tell el-Amarna and what appeared to be the outhouse of a large estate. In a small courtyard to the east, Mr Pendlebury was supervising a Bedouin workman in what seemed to promise to be a useful day’s effort. They had already found a small limestone statue of a monkey playing a harp and a fragment of pierced blue faience decorated with spirals and a Nefertiti cartouche.*43 Digging a foot under the ground the workman unearthed a large buff-clay, matt-brown painted jug. It was about 24cm high and 15cm diameter. As he prised off the lid, out popped a gold bar, followed by twenty-two more.

By the time they had completed the excavation, the team had also found two silver ingots, silver fragments, rings, ear rings and silver sheet.

Dr Frankfort believed that the silver fragments had been crushed and the rings twisted and broken, to make them ready for melting down, just the way the silver and gold ingots had been produced. Frankfort and Pendlebury considered that the find was part of a thief’s loot, and even suggested that the looter, or looters, had raided the Hall of Foreign Tribute, as it was less than a mile away.

The area that they were excavating is now known as ‘Crock of Gold Square’. What Dr Frankfort and his team had found was a treasure trove of twenty-three gold bars of various weights between 34.62g and 286.53g, and weighing 3,375.36g in total.15

Before proceeding to assess this find we need to re-examine the question of what the text of the Copper Scroll really means when it refers to a ‘Talent’.

The Problem of Weights and the ‘Gold Khaff Link’

The difficulties in determining what exactly was meant by the unit of weight that is written in the Copper Scroll texts as ‘KK’, and sometimes just as a single ‘K’, has continually perplexed translators. The unit is usually translated, and therefore considered to be, a ‘Talent’.

The weight term is represented in the text as two Hebrew ‘khaffs’, for which there is no exact English pronunciation but an approximation would be ‘kh kh’. These weight letters have always previously been translated as the Canaanite or Biblical ‘Talent’ – a unit weighing variously between 30kg and 150kg. For the Copper Scroll, 35kg (equivalent to the weight of 3,000 Shekels) has usually been taken as the guide. Using even the lowest of these units, astronomical financial values and excessive weights are arrived at for the total amounts of precious metals mentioned in the Copper Scroll. Some translators have, therefore, quite arbitrarily downgraded the term to the next Canaanite unit of weight.16 (For further discussion of this point, see Chapter 2.)

From my standpoint that the texts refer to Egyptian locations, I considered it more logical now to use local contemporary Egyptian units of weight. In addition, drawing on my experience as a metallurgist, I knew (as anyone who has been in an assay office would know) that units of ‘kilogrammes’ are not the currency for weighing precious metals.

The Egyptian common unit of weight was, until 1795 BCE, the ‘Deben’ – equivalent to 93.3g. After that period it was supplemented by the ‘Kite’ of 9–10g – which was exclusively used to weigh gold and silver.17

Our worthy gentlemen, Dr Frankfort and Mr Pendlebury, and their team of excavators at Tell el-Amarna, also dug up a number of small decorative figures that they classified as weights. All are in the range of 20g, but only one looks like a standard weight. It is made solely of lead as a plain cuboid and is inscribed with two parallel vertical downward marks ‘II’. This was found in one of the most sumptuous houses amongst the large estates. These downward marks are identical to the type of single marks found in the Copper Scroll to indicate one unit of weight.

The weight of this lead cuboid is 20.4g. The two parallel downward strokes on it indicate that it was equivalent to two ‘Kite’ and must mean that the standard unit of weight – a ‘KK’ – is represented by the two ‘khaffs’ in the Copper Scroll.

The Copper Scroll only mentions pure gold ingots twice; on both occasions each reference is in the first two columns, which I have deduced relate to the City of Akhetaten. The total number of gold bars listed, from both locations, is 165. Assuming the gold bars were originally cast in identical, standard moulds, sized to produce gold bars as close as possible to the standard ‘KK’ unit of weight, the total weight of the 165 gold bars would be:

165 x 20.4g = 3,366g

This is virtually identical to the total weight of gold (3,375g) found at the ‘Crock of Gold Square’ in Amarna. The correlation is so close in fact (within 0.28 per cent or 99.72 per cent probability of correctness) that, bearing in mind the technical difficulty of consistently pouring the liquid gold into the original standard moulds to the exact level mark, the degree of certainty that they were the same gold bars the Copper Scroll refers to is virtually 100 per cent.

Clearly, as Dr Frankfort surmised, the thief had melted down the 165 light gold bars to produce twenty-three ingots, of varying sizes and weights, from his crude sand moulds.

If this is what transpired, we would expect some of the new ingots to weigh a multiple of the ‘KK’ 20.4g unit weight, purely on statistical grounds, particularly the larger ingots. This is just the case, and the largest of the new ingots is almost exactly fourteen times the ‘KK’ unit weight. (The twenty-three gold ingots from ‘Crock of Gold Square’ are in the Cairo Museum, and many of the silver and jewellery items are on show in the British Museum, London).

So, our thief had found the hoards hidden at the sepulchred monument and from the Hall of Foreign Tribute and had found a nearby house to sort through his plunder. He was also busy melting down silver, approximating to 40 KK, and other jewellery, perhaps from the hoard at Column 1’s ascent of the staircase of refuge where there were forty Talents of silver.

This finding that the gold bars mentioned in the Copper Scroll weighed almost exactly the same as a hoard of gold bars discovered at El-Amarna in the 1920s is virtually certain proof that I have made a correct interpretation of the Copper Scroll. More significantly, it puts a lock at the end of a chain stretching through the centuries that links the priests of Akhetaten to the Essenes of Qumran – a twenty-four Carat gold link!

Are there any other ‘finds’ in the region of Akhetaten that back up this conclusion? When we come to Column 6 of the Copper Scroll we will discover there is indeed another ‘gold link’, and although not quite so clear cut as the above example, it is still very convincing.

My conclusion is further reinforced by an astonishing design characteristic of the jar in which the treasures from the ‘Crock of Gold Square’ were found. All the jars in which the Dead Sea Scrolls of the Qumran-Essenes were found were unusually large. They are unique to the Essene Community who must have made them, and they are not found elsewhere in Judaea or ancient Israel. They have a mottled white coloured exterior with a squat curved lid. They vary in outline shape, maximum diameter and height, but virtually all have a lid diameter of 15cm – exactly the same diameter as the ‘Crock of Gold’ jar found at Amarna (see Plate 11). There is also a marked similarity in base design and size, and in lid design.18

Not to worry that some of the treasure has been found. There are still sizeable amounts not yet located!

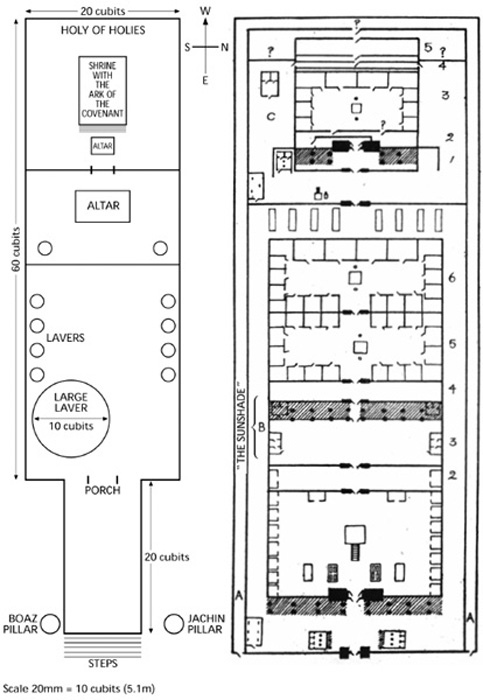

Returning to the Column 1 text, we are probably still in the city centre and the next description is of a building with a peristyle courtyard (i.e., surrounded by columns) with a large cistern and a floor covered with sediment. Assuming the building is the Great Temple, its outer part had a colonnaded court that must have contained the Great Cistern, supplying water to the Temple area and the eight bathing tanks that stood at the back of the Temple. In front of the upper opening: 900 Talents.

Still near the Seventh Year Store we are told to look somewhere in the Place of the Basins: there, at the bottom of the conduit that supplies the water, six cubits down from the edge of the northern basin we will find vestments and tithes*44 of treasure. The Garcia Martinez translation of the section refers to the second tithe made unclean, implying contact with the dead or a sacrifice, and therefore proximity to burial chambers or places where offerings of animals might have been prepared.

These basins, of which there were eight, stood outside the Lesser Sanctuary housing the ‘Holy of Holies’ or ‘Benben’ of the Great Temple and were supplied in series by a main conduit from the Great Cistern. As the Temple was oriented approximately east to west lengthways, the northern-most basin was probably the first one connected to the water conduit. The Garcia Martinez translation can be explained by the proximity of this part of the building to a preparation area.19 These preparations would also have required large amounts of cleansing water. It appears, therefore, that 9m from this northern-most basin in, or near, the supplying conduit, the treasures were hidden.

Finally in Column 1 there is a phrase that Garcia Martinez (and Al Wolters) translate as: in the plastered cistern of Manos. He has, perhaps, been influenced here by the Greek letters scattered in the text and comes up with a Greek name – which is not very helpful! Manos is a legendary character, portrayed in the film Manos the Hands of Fate who encounters Torgo – a type of monster with huge knees who has trouble walking.20 Somehow I think the translators were on the wrong track here!

John Allegro translated the critical phrase as Staircase of Refuge, and Geza Vermes has it as In the hole of the waterproofed refuge; these probably allude to the Temple and could possibly refer to the screened portico section of the building known as ‘The Sunshade’.21 But as we know, Dr Frankfort’s thief has already cleaned out this cache.

At the beginning of Column 2 there are said to be forty-two Talents (KK), in the filled tank which is underneath the steps. John Allegro and Al Wolters disagree with Garcia Martinez and translate filled tank as in the salt pit…. Either way, the steps may well be those depicted on the walls of the Tomb of Panehesy and shown in Plate 18 of N. de G. Davies’ Rock Tombs of El Amarna – Part II. They are the steps up to the Great Altar of the Temple, which stood in the centre of an open courtyard and was approached by a flight of seventeen steps.

The space within the altar and under the steps was used for storing offerings, and if the offerings were meat they would have been preserved by salting. N. de G. Davies, however, takes this usage as only being ‘sculptured on the sides’ of the altar. If this assumption is correct then the space under the steps could well have provided accommodation for a water storage tank to supply the two lavers, or basins, which stood next to the altar. Geza Vermes’s translation of in the cistern of the esplanade then makes much more sense.

The steps leading up to the altar are illustrated in Figure 6 – the Egyptian tomb inscription showing the assumed figure of Joseph.

Column 2 continues, according to Garcia Martinez: In the cellar which is in Matia’s courtyard. Two Hebrew letters in the name ‘Matia’ overlap and appear to have been translated as a tav – the Hebrew letter for ‘t’. Separated, the letters would translate as raysh and vahv, the Hebrew letters for ‘r’ and ‘v’ respectively. This then gives a rather different translation for the name of the courtyard – ‘Marvyre’. There is one name that is remarkably close to this sound: ‘Meryre’ or ‘Meryra’ – who was the High Priest of Aten. His name has been identified from tomb inscriptions in the group of Northern Tombs at Amarna, described previously. If this translation is correct, there was a cistern in the cellar or lower part of his house in Akhetaten and hidden in it were seventy Talents of silver.

Meryra’s house in Akhetaten was located near to the Treasury. It stood at the corner of a large walled-in courtyard. Deeper excavation of the house, to locate its cellar, could pay dividends to the tune of seventy Talents (KK) of valuables. Attached to the estate, beside the stables, was an Eastern Garden with a small park of trees, and servicing these trees were two large walled-in water tanks with steps leading down their steeply sloping sides. The tank in the middle of this small grove of trees could also have concealed the seventy Talents (KK) of silver, submerged at the bottom of it.

It would also be worthwhile looking more closely at the tank that stood some 7.65m in front of the Eastern Gate of Meryra’s house, for vessels and ten Talents (KK) of valuables.

John Allegro, however, translates this section in Column 2 rather differently, as:

In the underground passage which is in the Court a wooden barrel(?) and inside it a bath measure of untithed goods and seventy Talents of silver.

I consider that there are two plausible possibilities for this particular hoard of treasure, as, if John Allegro’s translations are correct (which I do tend to go along with), then this and the next series of descriptions all relate to treasure still hidden within the Great Temple at Akhetaten. John Allegro’s translation of untithed goods also implies a location within a Temple environment. The seventy Talents of silver, in John Allegro’s version, were therefore hidden in an underground passage of the Temple Court.

The front and back halves of the Great Temple, shown in a modified cross-sectional drawing on the west wall of the Tomb of Panehesy, clearly show activity in subterranean passages, below the line of the Temple. However, these underground passages only appear to emerge in the upper, back-half part of the Temple, in the Court of the Inner Sanctuary, close to where the King sits by the altar.22 Here, no doubt, was a need for water and other offerings to be ‘bucketed up’ to the Sanctuary that, in itself, was difficult to reach and heavily secured.

The next three locations from Column 2 are of ten Talents of metal in a cistern 19 cubits (9.7m) in front of the Eastern Gate to the Temple (Garcia Martinez says 15 cubits or 7.65m); 600 pitchers of silver in the cistern under the Eastern wall of the Temple near what was the Great Threshold; and twenty-two Talents of treasure buried in a hole 2m deep, in the Northern corner of the pool in the Eastern part of the Temple. Archaeological work has shown that the Great Temple may only have had one gate, and that was an Eastern one. I take this as further confirmation that we are at the right Temple. The Copper Scroll descriptions for the above three locations are therefore fairly unambiguous, although there were two Eastern Gates – one outer and one inner. The inner Eastern Gate opened onto the Greater Sanctuary, where there were two lavers immediately in front of the Gate, which would have needed a water supply. It would seem prudent to re-excavate the area between 7.65m and 9.7m going inwards from both gates.

Still in the Great Temple at Amarna, Column 3 pinpoints 609 gold and silver vessels, comprising sacrificial bowls, sprinkling basins and libation containers 9 cubits (4.6m) under the Southern corner of the courtyard, and forty Talents of silver at a depth of 16 cubits (8.16m) under the Eastern corner of the courtyard. Unfortunately the Copper Scroll is too damaged at this point to tell to which Court of the Temple is being referred. It would therefore be sensible to excavate to the recommended depths at the Southern and Eastern corners of all eight courts and forecourts within the Temple!

Continuing in Column 3 there is a very interesting phrase: In the tunnel which is in Milcham, to the North: tithe vessels and my garments.

John Allegro translates Milcham as some funerary structure. My garments, which are elsewhere also called vestments, seems to strongly indicate that the writer of the original Copper Scroll was a priest, and probably the High Priest. This deduction ties in with the description of tithes and the Temple-related locations we have isolated. It could also help unravel the last six Greek letters in the text that I have not yet deciphered:

Δ I # T P # Σ Κ

The Puzzle of the Remaining Greek Letters

Σ Κ are the last of the Greek letters to appear in the first four columns that relate to Egypt. Perhaps these two letters are also the missing ones from the very end of the document, which I would expect to have been signed off on behalf of the High Priest. Σ Κ would then have been the most appropriate Greek abbreviation for the Qumran copyist to have used for the traditional name of the High Priest of the Jewish Temple…Zadok. Zedek, from which the word Zadok was derived, also meant priest in ancient Egyptian.*45

What we also have is a title closely associated with the Qumran-Essenes. The connection of ‘Zadok’ to the Qumran community was made well before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, in Genizah fragments**46 found in Cairo in 1896, confirming the affinity between the two sources.23 These Genizah fragments have variously been referred to as ‘The Zadokite Fragments’24 or ‘Cairo-Damascus’ texts, and it has been generally accepted that the Qumran-Essenes were a ‘Zadokite Priestly Sect’.25 In their own writings the Community refer to themselves as the ‘Sons of Zadok’26 and some interpreters have equated their leader – ‘The Teacher of Righteousness’ – to ‘The Zadokite High Priest’27 with a sequential role for the ‘Sons of Zadok’ as guardians of the Ark and the Commandments, going back at least to the time of Aaron. Column 7 begins: Priest dig for 9 cubits…

The four Greek letters that still remain, and which may not be complete, are somewhat puzzling

Δ I # T P

To try and solve the problem I again approached it from the end – using the clues I already had to work backward towards the answer. On the basis that the original document from which the Copper Scroll was copied was written by the High Priest of Akhenaten, and from those texts I had deduced that some of the locations described were in the Great Temple of Akhetaten, I felt that the four remaining undeciphered letters could well be a more general reference to the location of the Great Temple.

Going back to the original text, only the Δ T P are clear and unambiguous. The second letter, which has been taken to be the Greek capital letter ‘Iota’, is nothing more than a tiny ‘floating’ vertical line. It could quite easily have been part of a capital Greek ‘Lambda’. The four letters would then come out as pronouncing the word: DELTRE.

If, however, the Qumran-Essene scribes wished to use a Greek word for ‘Temple’ there are few more appropriate than the most famous Greek temple that would have been within their purview – DELPHI. For the ancient Greeks, this was the centre of the world and was once the site of an oracle of the goddess Gaea, subsequently replaced by that of Apollo and Dionysus.

If the fourth letter had been a Greek ‘Phi’ this explanation would have been a lot more convincing. So possibly the four letters do simply refer to the DELTA area.

Going back to Column 3, the location for tithe vessels and my vestments is at the entrance to a funerary structure, beneath its western corner. The scroll goes on to describe a tomb to the north-east of the structure where there are thirteen Talents of valuables buried 1.5m below the corpse.

We appear to be back at the Northern Tombs. The thirteen Talents are described by John Allegro as being in the tomb which is in the funerary structure, in the shaft, in the north. If the original scribe is the High Priest Meryra, talking about his vestments, we must be at his tomb and looking for a shaft. John Allegro’s translation seems to be correct, as directly beyond Meryra’s tomb, some 61m to the north, there is indeed a deep burial shaft on the summit of the ridge. Although this shaft has been plundered, it could pay dividends to dig further down this shaft, well below where a corpse would have lain.

The vessels and vestments are therefore located at the western corner of the entrance to Meryra’s tomb.

Column 4

Unfortunately a number of words are missing in the first part of Column 4, and we can only interpolate the textual description of where fourteen Talents are hidden. We are directed to:

The large (great) cistern in the…in the pillar of the North…

We seem to be back in town now, or near it, as the next passage refers to fifty-five Talents of silver in a man-made channel. We can only speculate that the Great Temple and the Great Palace needed a Great Cistern to supply them both with water. If this is the case, then there are fourteen Talents in the hole of a pillar near the Great Cistern of the Palace or Temple at Amarna. The fifty-five Talents of silver are 20.9m up the channel from the Great Cistern.

Further out from town there are two jugs filled with silver, between two buildings [possibly oil presses] in the valley of Aton. They are buried midway between the two oil presses at a depth of 1.53m.

Still near presses, but this time ones used for wine, and in the clay tunnel [or pit] underneath it there are 200 Talents of silver. The location of these ‘presses’ is discussed more fully in Column 10.

Penultimately, in the eastern tunnel to the North of the Store House of the Seventh Year produce: Seventy Talents of silver. Perhaps this is the tunnel that ran east to west under the front section of the Great Temple, or might even have connected the storehouses with the Temple.

For the final paragraph of Column 4 we appear to be in a different valley:

In the dam sluice [burial mound?] of the Valley of Secacah, 1 cubit down there are twelve Talents of silver

Column 5 also talks about Secacah, and it is tempting to associate this translation with the Old Testament reference where the land of Canaan is being allotted to the tribes of Israel. Judah are to take control of land:

In the wilderness, Beth-arabah, Middin, and Secacah, and Nibshan, and the city of Salt, and En-gedi; six cities with their villages.

Joshua 15:61–62 (my italics)

There is archaeological evidence that Khirbet Qumran was occupied in the Israelite period as early as the fifth century BCE,28 and that Secacah might have been the ancient name for Qumran. (The site was apparently deserted between 600 BCE and the time of the arrival of the Qumran-Essenes, c.200 BCE.) Unfortunately the exact whereabouts of ancient Secacah is unknown and in his search for the city John Allegro, like many others, was unable to locate it.

However, even though there is also an adjacent translated reference to Solomon’s trench, I am not convinced we have yet left Egypt. John Allegro, in fact, annotates his translation of Solomon’s reservoir (or trench), which occurs in conjunction with the word ‘Secacah’, as a technical description of the shape and function of this type of reservoir. If we are still in Egypt, ‘Secacah’ could easily be to the north of Akhetaten, at ‘Sekkara’, or Saqqara.

Saqqara was the main cemetery for Memphis, dating back to 3000 BCE, and contains burial sites from the First to the Sixth Dynasties, and enormous shaft-tombs from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. It is dominated by the huge step pyramid of King Djoser of the Third Dynasty, dating to 2700 BCE. Much of the area is still unexcavated. Work that has been done, digging down through the layers of Roman and quarry debris, shows the remains of Eighteenth Dynasty chapels and burial chambers, indicating that burials were taking place here at the time of Akhenaten.

Reference in the Copper Scroll to burial mound (as opposed to tomb) is perhaps significant. The earliest part of the cemetery is to the north and is densely packed with mudbrick Mastaba or burial mounds. Plate 13 shows the burial district at Saqqara.

Column 6

Column 6 brings us back to the Temple, in the inner chamber of the platform of the Double Gate, facing East… This is fairly unambiguous. There was only one Double Gate facing east in the Great Temple of Akhetaten, and the inner massive doors consisted of two solid, corniced towers with jambs projecting from the inner face. To quote N. de G. Davies:

The Passage (to the Outer Court) was barred by two double-leaved gates. The inner one being high and unwieldy, a similar but smaller gate was set within its jambs, contracting the passage.29

The location for our treasures is therefore: ‘In the Northern entrance (tower), buried 3 cubits (1.5m), is a pitcher containing one scroll, and beneath that forty-two Talents (KK).’

Paraphrasing the next piece of text, we have buried 9 cubits (4.6m) under the inner chamber of the watch tower that faces East, there were twenty-one Talents (KK). Security of the Great Temple was obviously of prime importance, and as well as double protective walls and gates, armed guards would have been on constant duty. The ‘watchtower’ is depicted in various inscriptions of the Great Temple as a Pylon-like structure, ‘formed by a portico of columns, eight in line and two deep, broken by the entrance (to the East), and with towers and masts reaching high above it in the centre’.30

You will recall that after the ‘Crock of Gold’ find pinpointed in Column 1, I mentioned there was another convincing ‘gold link’ between the Qumran-Essenes and Akhetaten. The next part of Column 6 takes us to this link: In the Tomb (?) of the Queen, in the western side, in John Allegro’s version.

This phraseology must be assumed to refer to the burial place of either Queen Tiyi, or Queen Nefertiti, respectively, Akhenaten’s mother or his wife.31

Garcia Martinez takes the key word to be her ‘residence’ rather than ‘tomb’, and John Allegro is not too happy with his own translation of ‘tomb’ as he equates the word here with ‘dwelling’. However there is no evidence that Nefertiti (or Tiyi) had her own Palace, other than the one she shared with Akhenaten in Central Akhetaten – unless the Northern Palace was her preferred place of residence, some 3.2km to the north.

A deeper excavation, down to 6.1m (12 cubits) in the western section of Nefertiti’s Tomb, located in the Royal Wadi, might reveal the twenty-seven Talents (KK) buried there.

Royal tombs would, of course, be the most vulnerable to tomb robbers and I fear that is exactly what has happened to the 27 KK. I consider that this reference in Column 6 is once again to items that have already been found; the items now reside in Edinburgh, Scotland and in Liverpool, England!

In 1882 local grave-robbers found a number of articles of gold jewellery near or at the tomb of Nefertiti. Villagers of Hagg Qandil, near El-Amarna, later sold them to the Reverend W. J. Loftie, a collector of Egyptian relics. He, in turn, sold the trove to W. Talbot Ready in London. Loftie kept back two rings for himself, which later came into the possession of the author Sir H. Rider Haggard, and eventually the City of Liverpool Museum where they now reside. The London dealer sold the balance of jewellery to the Royal Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, where they might have lain unrecognized to this day were it not for the astuteness of Professor A. M. Blackman. Re-examining the find in 1917, he concluded that some of it was from the Eighteenth Dynasty, particularly a heavy gold signet ring incised with the cartouche of Nefertiti, a ring with a frog-shaped bezel inscribed ‘Mut Mistress of Heaven’, and two ear studs embossed in the shape of a flower bloom. The jewellery from Hagg Quandil is shown in Plates 14 and 15.

Figure 20: Schematic of Solomon’s Temple and the Great Temple at Akhetaten.

Considering this information, my guess was that if the Eighteenth-Dynasty items were separated from the non-Eightenth-Dynasty items in the Edinburgh collection, and the two rings that our reverend gentleman kept back were added back in, the total weight would come to either 183.6g or 550.8g – these weights being specified in the Copper Scroll according to the three main translators, when using my Egyptian value of 20.4g for the term KK. John Allegro reads the reference to the weight of the treasure in Column 6 of the scroll as 9 KK, whilst Garcia Martinez and Geza Vermes (whom I go along with on this occasion for technical reasons) translate it as 27 KK.

When we add up the weights of all the Eighteenth-Dynasty gold items and the gold/precious bead necklaces that came from the original Hagg Qandil find, the total weights come remarkably close to 560g – almost exactly the weight specified in the Copper Scroll.32

Column 7

Finally in Column 6 and at the beginning of Column 7 we are led by John Allegro to: the dam-sluice(?) which is in the Bridge of the High Priest…

Meryra’s house has already been mentioned. It was probably next to the Treasury, and as High Priest he commanded a view overlooking the Nile and would have had a private walkway access to the Great Temple. His extensive eastern gardens were watered by a large storage tank, served by water from the River. An indecipherable number of Talents (KK) are buried perhaps 4.6m down, by the sluice gate feeding the two large walled-in tanks.

The next injunction, at the beginning of Column 7, is: Priest, dig for 9 Cubits: Twenty-two Talents in the channel of Qi… Much of the Scroll is missing here and any interpretation is guesswork. If the injunction applies to the previous location, then there may be valuables anywhere along the length of the channels feeding Meryra’s garden tanks.

The Northern reservoir or cistern for this garden to the East of Meryra’s residence has 400 Talents (KK) somewhere within 10.2m of its perimeter.

Apparently still in the garden of Meryra, there was an inner chamber which is adjacent to the cool room of the Summer House, buried at 6 cubits: six pitchers of silver. One of the buildings in this garden area is described in the Rock Tombs of El Amarna – Part I as being ‘of striking security’. It was built to be impregnable – a very unusual structure to find in a garden. From its description getting inside this building must have been like navigating the Maze at Hampton Court Palace.

The only access is by the triple entrance in front, and he who passed it was immediately confronted by another and similar one. This also passed, the visitor was in an open square with thirteen almost identical doors to choose from, and only the three (two?) least promising of these enabled him to gain the innermost rooms, twenty-one in number. Moreover, each one of these only led into one of three blind corridors, flanked on one side with rooms…33

The innermost chamber of this building must have had a large amount of silver buried 3m under its floor.

The next instruction is to look In the empty space under the Eastern corner of the spreading platform, buried at 7 Cubits: Twenty-two Talents.

There were two large walled-in watering tanks feeding the garden, and each had a small enclosure opposite its steps that suggest some additional purpose. These enclosures appear to have provided a table or platform, used preparatory to sliding something into the water. There is only one eastern table, which must be the one being referred to in the scroll. Buried 3.6m under it there could be 22 KK.

Assuming the water tanks were fed in series there was an outlet pipe, or conduit, from an overflow tank, and 1.5m back from this outlet were buried 80 KK of gold or, according to Garcia Martinez, 60 KK of silver and 2 KK of gold.

Not far from the Great Temple and the Royal Palace, perhaps even interconnecting with the Palace, was to be found the Treasury. On a private connecting road to the Palace running east from the Treasury there must have been a channel or drain pipe going into the building just by its entrance. Here, buried by this ‘drain pipe’, were tithe jars and scrolls and possibly silver.

Further afield, we are in an Outer valley looking for a Circle on the Stone, or circular shaped stone. Deliberately shaped ancient circular stones are not that common a sight in Egypt. The one described must have been immediately recognizable as being unique.

The most notable of these that comes to mind is a huge, monolithic, alabaster circular slab whose remains can be found at Abu Gurab on the West Bank of the Nile, between Giza and Saqqara (see Plate 13 (bottom)). In the centre of the ruins sits a massive circular disc surrounded by four hetep (offering) tables. The slab served as an altar at the Sun Temple of the Fifth-Dynasty King Nyussera, who lived from 2445 to 2412 BCE:34 17 cubits (8.7m) under the slab there could be 17 KK of silver and gold.

ON INTO ISRAEL?

John Allegro now conveys us to Israel and the Kidron gorge, but Garcia Martinez reckons we are still: In the burial mound which is at the entrance to the narrow pass of the potter. John Allegro’s clues prove not very useful. Taking the second translation, burial mound generally implies older or more modest tombs. If we assume we are still looking at the burial areas of Akhetaten, the smaller Northern Tombs become possible candidates for investigation. Beside the series of tombs that run along the hillside to the north of the City, there are a few of unspecified date within the hills.

By a gap in the hillside and a central ravine, there is a track that leads up into the hills towards a tomb N. de G. Davies classifies as No. 6.35 To the right of this path is a burial place and there are four more ancient burial sites scattered along this part of the hillside. In front of these tombs there are traces of a small community settlement. There is evidence that within this community, living by a narrow pathway that led up into the hillside, there was an active pottery utilizing local clay materials. This site has also been identified as being in use as a pottery in late Roman times by Professor W. Petrie.36 The burial mound nearest to the street of the potters’ pass is the most likely place to dig for 3 cubits; four Talents.

The subsequent descriptions of Column 8 are particularly intractable and vague. We are in the Shave – a plain or cultivated area that perhaps lies to the South-West of the Northern hills. In an underground cellar or passage that faces north there are sixty-seven Talents. Nearby in the irrigated part of this cultivated area there is a landmark, and there are seventy Talents buried at 11 cubits.

The first direction could be referring to a set of isolated altars that lie southwest of the Northern hills of Akhetaten in the open plain. A dry watercourse runs out from the hills in this direction, indicating that irrigation water was available. Excavation of the altar and chapel buildings shows that they were used in the time of Akhenaten and fragments of gold leaf have been found near the Northern Altar.37 Some 600m from the Northern hills, near to the path of the watercourse, there is a brick platform that might well be the landmark of the second direction. Buried 5.6m under, or by an irrigation channel near this platform, are 70 KK of precious metal.

Column 9

Column 9 is again particularly obtuse. John Allegro guides us back to the First Temple at Jerusalem. Here he locates various likely places for treasures. Whilst I have already indicated that I believe some of the treasures of the Copper Scroll originated from the First Temple, the possibility that some may also have come from the Second Temple cannot be completely ruled out. Unfortunately both sites, which must have been fairly adjacent, are either inaccessible for excavation for religious reasons or have so far proved fruitless.

However, assuming we are back at the Great Temple of Akhetaten, Garcia Martinez gives some additional clues by imputing a dovecote as being mentioned at the beginning of the paragraph. The first Hebrew word reads bsovak, and almost certainly means dovecote. We know that doves formed part of the Temple ceremonies so it is reasonable to assume that they were kept in the vicinity. However, the usual place for a dovecote would be in the upper part of a building near to the altar courtyard. The instruction to dig for 1m under seven slabs would seem, therefore, rather incongruous.

I believe the solution lies in the representational form of many ancient Egyptian drawings, where the artist combines external images into his perspective.

The drawings on the east wall of Huya’s tomb at El-Amarna show what appear to be pastoral activities at the base of the Temple, but the only scene that contains a defined enclosure has doves flying inside and around it. In the lower sections of the drawing all the figures are stooping, indicating that they are working in underground cellar levels of the Temple. The positioning of the framed dovecote drawing implies a device of the artist who wanted to represent it as being both under and outside the Temple. A possible conclusion is that the main storage place for the doves was in an underground passage of the Temple, but some were kept at the top of the Court of the Great Altar. In fact, a straight line connects the drawing of the doves at the bottom of the Temple to the symbol of a dove at the top of the building.38

Figure 21: Plan of the Second Temple at Jerusalem, dating from 515 BCE. It was fully restored by Herod the great in 20 BCE.

The most likely place, therefore, to dig for four bars of precious metal would be approximately 6.6m in from each corner of the wall surrounding the Great Altar Courtyard, along the line of the wall to a depth of 1m. But as we are talking about a subterranean passage it would be sensible to go much deeper than the floor level of the Temple. If you come across seven slabs you are there!

In the Second Enclosure, which equates to the Courtyard of Rejoicing, in the cellar running east there are 22.5 KK at a depth of 4.1m.

A further 22 KK are hidden at a depth of 8.2m in the passage of the Holes running south. This would seem to be the cellar running south under the laver building in the Inner Sanctuary where the drainage shaft entered.

I have already noted how the Qumran-Essenes seemed to know the orientation and layout of the City of Akhetaten. A close analysis of the description given in the Qumran Community’s Temple Scroll will demonstrate that they also knew about the inner layout and function of the Great Temple at Akhetaten. Comparing descriptions in the Temple Scroll with reconstructed drawings from wall inscriptions at El-Amarna, it can be seen that The Great Temple had a ‘washing building’ to the south-east of the Sanctuary, where residues from sacrifices were dealt with by channelling them down a shaft into deep holes in the ground away from the Temple.39 Compare this to sections from Columns 31 and 32 of The Temple Scroll:

You shall make a square building for the laver, to the south-east, all its sides will be 21 cubits, at 50 cubits distance from the altar…

You shall make a channel all round the laver within the building. The channel runs from [the building of the laver] to a shaft, goes down and disappears in the middle of the earth…

In the shaft or funnel itself were secreted silver offerings. ‘Funnel’ might also be translated as bekova or helmet, implying a location at the top of the drainage shaft. The outlet to this conduit must have led to a drainage basin and to the east of this, at a depth of some 3.6m, was buried 9 KK of metals.

More consecrated offerings were to be found in the sepulchre that is in the North, at the mouth of the gorge of the Place of the Palms. We now appear to be back at the foothills to the north of Akhetaten, looking for another burial monument. The narrow pass appears to be the same ‘potter’s pass’ we encountered in Column 8. Reference to a Place of the Palms, at the outlet of the valley, indicates we are on lower ground, near water. This therefore may be in the area of the community that lived by this pass entrance, perhaps in the vicinity of the same burial mound indicated in Column 8.

Four options face us for the last clue in Column 9. The key words from Garcia Martinez are dovecote and Nabata, whilst John Allegro comes up with gutter and Sennaah. Both agree that the location is a fortress or stronghold.

Could it possibly be the Castle or Fort of Aten? This was located about 500m south of the Great Temple of Akhetaten. The second floor gutter or dovecote of this building is, of course, long gone and the chances of finding the 9 KK stored there negligible…but somewhere in close proximity?

Column 10

Column 10 presents its own problems. From the last six lines, through to the last few lines of Column 12, the instructions have almost certainly switched to locations in Canaan/Israel. There are pointed references to Absalom’s tomb, the Siloam conduit of Jerusalem, Zadok’s tomb, Jericho and Mount Gerizim.

Assuming, however, that the first lines of Column 10 still refer to Egypt, we are initially looking for a cistern or irrigation structure by a great stream and a Ravine of the Deeps.

The translation of the Hebrew ‘nahal hagadol ’ as great stream or great river has been studied in great detail by many researchers, including B. Pixner, J. Lefkovits, Jozef Milik, F. Cross, and Stephen Goranson.40 To quote Lefkovits, ‘it is a mystery to which river or wadi the “Great River” refers’. With our Egyptian perspective the ‘Great River’ can surely be none other than the River Nile – a term which was often used by the ancient Egyptians to describe it.

One can only imagine that the Ravine of the Deeps must have been what is now a very large (and for most of the year), dry watercourse that runs south from the Northern hills through a deep ravine midway between the line of Northern Tombs at Akhetaten, alongside the Nile. In ancient times this ravine was swept by occasional torrential rains collected on the limestone hillside. Somewhere along the line of this dry watercourse is hidden the remains of an ancient irrigation waterwheel; buried at its foot lies 12 KK of treasure.

Both Garcia Martinez and John Allegro agree that the key phrase in the next section of Column 10 is ‘Beth Keren(m)’ – the House of the Vineyard. By its water reservoir are hidden 62 KK of silver. The lower slopes of the Northern Hills of Amarna have, through the ages, sustained continuous weathering and denudation of topsoil. It is only in the well-watered, cultivated areas nearer to the Nile and to the large watercourse, which must at one time have provided good water supplies so that substantial cultivation could be sustained.

Here the ‘North City’ suburb of Akhetaten nestled between the curve of the River and the beginnings of the meandering slopes of the Northern Hills. On the gentler slopes at the foot of the Northern Hills, olive trees could have been sustained and vines cultivated on the facing plain. Perhaps the brick platform, located along the line of the watercourse in this vineyard region, was the structure that supported the heavy stone slab measuring 2 cubits across needed to press the precious oils from the olives. In one of the large storage vats of this agricultural area 300 KK of gold and some twenty libation vessels were secreted.

ON INTO CANAAN?

The Copper Scroll text now appears to move irrevocably into Canaan, with a reference to ‘Absalom’s memorial’. One would therefore expect some (if only a cryptic) marker to that effect. Untidy as our scribe (or scribes) was, he never placed a letter completely out of alignment – except at this item where a Hebrew ‘kaff’ appears at the side of the Column – the same sound that starts the Hebrew word for Canaan. This is presumably the scribe’s ‘marker’ that indicates that we have moved to Canaan. The treasures we are looking for are, therefore, either treasures that have been dug up and brought from Egypt or, more likely, treasures hidden at the time of the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE.

There are three possible candidates for Absalom’s Monument. One is a structure built in the first century BCE, in the Valley of Kidron, for King Alexander Jannaeus – a descendant of the House of Absalom. The second is the tomb of Absalom, the third son of King David, and the last is the resting place of a patriot rebel leader named Absalom, who fought the Romans at the beginning of the Jewish uprising. Both of our last two candidates died in battle and there are no known monuments to them or their deaths.

The first location is the most northerly of the Hellenistic tombs to the east of the Kidron Valley, which is associated with a marble column that Josephus mentions as being ‘two stades’ distant from Jerusalem. We are told by the Copper Scroll to dig on the west side for 12 Cubits (6.2m). There is indeed an opening on the western side of the Monument. The opening leads to an underground cistern that is almost exactly 6.2m deep, giving credence to this as the location mentioned in the Scroll for 80 KK of treasure. No trace of the treasure has so far been found at this site.