“You can get everything in life you want, if you will just help enough other people get what they want.”

— Zig Ziglar

Most successful people in business learned how to negotiate on the job. They would have gone to a few meetings with their boss and watched her in action, then they would have taken the lead in the next few meetings as their boss sat back and watched, and after a few of those meetings the boss would have said, “Congratulations, you are now a negotiator!” and left them to their own devices. Where did the boss learn to negotiate? From her boss, who learned from his boss, and so on, all the way back to the days of the cavemen. The art was passed down over centuries, but it was not the art of win-win negotiation, it was an adversarial, old-school, win-lose style of negotiating, sometimes called distributive, zero sum, or fixed pie negotiation.

Win-lose negotiators see negotiation as a pie to be divided, and they want the bigger slice. In other words, one person will win and the other will lose, so they do their best to win. How do they know when they have won? They see they have the bigger slice of the pie, or that their counterpart looks beaten. A loss for the other party is interpreted as a win for them.

This win-lose approach is only suitable for one-time transactions, where in all likelihood you will never see the other party again. In this situation, you probably don’t really care if the other guy loses. You might care, though, if you believe in fairness, or karma, or if you want to maintain a good reputation in a world that is getting smaller and more interconnected by the day. In an isolated instance, however, most people just want to win.

Throughout most of history the win-lose approach was the norm. Our caveman ancestors lived or died by the law of the jungle, eat or be eaten. But isolated, one-off negotiations are now the exception. Most of us must negotiate with the same people repeatedly over a long period of time: colleagues, customers, vendors, and partners. We need to achieve good results for our side while maintaining a healthy, long-term relationship with our negotiating partners. In today’s world, a win-win outcome is fast becoming the only acceptable result.

Take a look at your computer. Aside from the manufacturer’s brand, there are probably two or three other logos stamped onto the casing, such as Intel or Microsoft. When Intel and the computer manufacturer negotiate the price of computer chips, do you think either company would accept a win-lose result? Of course not! Both parties have lots of money, resources, expertise, and talent. They also have a long-term relationship that is more important than the outcome of any one of their many negotiations. Neither would accept a loss. They must both have a win-win result.

I suspect that you too would like to have a win-win agreement in most, if not all, of your negotiations. With the tips found in this book, your chances of negotiating win-win outcomes will increase exponentially.

Some wag once said this about the weather: everyone talks about it but no one does anything about it. That’s one of the first things that comes to my mind when I hear someone talk about a win-win outcome in a negotiation. Everyone says they want it, but very few people are able to achieve it with any regularity. In fact, few people even understand what it is.

A win-win is not just reaching an agreement. Nor is it a favorable outcome, or when both parties feel they have won. That is usually a partial win at best. A true win-win is when both parties get the best possible deal without leaving anything on the table. It is not just acceptable, it is optimal.

The elusive win-win is not easy to achieve, but you can learn how to increase the odds in your favor.

Win-win negotiators are found in the same places as win-lose and lose-lose negotiators. They are not any more experienced, and they look about the same as well. The big difference between win-win negotiators and all the others is their mindset.

Win-win negotiators understand the five styles of negotiating and are able to adapt to their counterpart’s style and to the situation. They choose to exhibit certain positive behaviors and avoid negative ones. They are optimistic, open-minded, and collaborate with their negotiating partner to solve their problems together. In this chapter, we will explore the mindset of a win-win negotiator.

In any negotiation there are several possible outcomes:

• Win-lose

One party wins, and the other loses. This can happen when the parties are mismatched, or when one party is not prepared. It can also result from cheating. In any case, the loser will resent the winner, and any relationship between the parties will suffer. Still, we would all rather win than lose, and it is easy to see how this result could come about.

• Lose-lose

Both parties lose. You may be thinking, “How can that be? It’s easy to see how one party might lose, but how can both parties voluntarily agree to lose? It just isn’t rational!” You’re right, it isn’t rational. It is, however, surprisingly easy to become emotional in a negotiation, and one may agree to lose so long as he takes the other person down with him. In addition, much depends on how you define “lose.” You might see a suicide bombing as a lose-lose, but the terrorist sees it as a win for him.

• Partial win-partial lose

This is by far the most common negotiating outcome. Both parties get part of what they want, but neither has his interests fully satisfied. This seems fair since both come out better off than they were, and we all understand that we can’t realistically expect to get everything we want. Or can we?

• Win-win

Both parties get everything they want! This is the best of all possible worlds! It’s the ideal outcome. But while the win-win is much talked about, much sought after, and much prized, it is rarely achieved. The main purpose of this book is to help make this outcome easier to achieve.

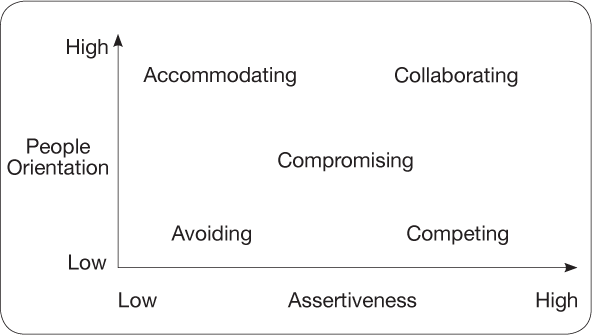

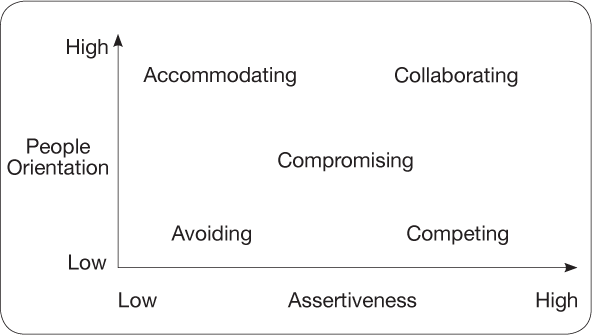

There are two dimensions that determine negotiating style: assertiveness and people orientation.

Assertiveness is the ability to communicate your interests clearly and directly. It means standing up for yourself without stepping on anyone else’s toes. Assertive people are able to ask for what they want, say no when they need to, and state how they feel in any situation. They also accept standards of fairness and recognize the rights and interests of others. They are able to advance their own interests without guilt or reservation.

People orientation denotes a sensitivity to the needs and feelings of others. It encompasses empathy, emotional awareness, and ease in social situations. Those with a high people orientation are generally sociable and likable. They are people driven rather than task driven, and they seek to understand their counterpart’s interests as well as their own.

Your negotiating style is a function of how assertive and how people oriented you are, as illustrated in this diagram:

1. Avoiding

A person with an avoiding style of negotiating avoids the issues, the other party, and negotiation situations as much as possible. An avoiding negotiator

• avoids confrontation, controversy, tense situations,

• avoids discussing issues, concerns—especially sensitive ones,

• is uncomfortable asserting her needs and saying no to her counterpart, and

• puts off negotiating whenever possible.

2. Accommodating

The accommodating negotiator is primarily concerned with preserving his relationship with the other party, even at the expense of his own substantive interests. An accommodating negotiator

• is uncomfortable saying no and focuses on the other party’s concerns more than his own,

• helps the other party at his own expense,

• tries to win approval by pleasing the other party,

• follows the other party’s lead, and

• emphasizes areas of agreement and downplays or ignores differences.

3. Competing

The competing style of negotiating is characterized by an emphasis on self-interest and winning at the other party’s expense. A competitive negotiator

• uses power to effect a more favorable outcome,

• exploits the other party’s weaknesses,

• wears the other party down until he gives in, and

• may use threats, manipulation, dishonesty, and hardball tactics.

4. Compromising

The compromising style places a premium on fairness and balance, with each party making some sacrifice to get part of what they want. A compromising negotiator believes she is unlikely to get everything she wants and

• is quick to split the difference,

• assumes a quid pro quo, give-and-take process is necessary, and

• seeks a solution in the middle of the range, without making much effort to find a win-win outcome.

5. Collaborating

Negotiators with a collaborating style seek an optimal outcome by focusing on mutual interests and trying to satisfy each other’s needs. A collaborating negotiator

• deals openly and communicates clearly and effectively,

• builds trust,

• listens to the other party,

• shares ideas and information,

• seeks understanding and creative solutions,

• considers multiple options,

• strives to create value, and

• sees negotiating as an exercise in joint problem solving.

Avoiding and accommodating negotiators generally do not fare well in negotiations, especially when their counterpart has a stronger style. They tend to be soft and are not comfortable being firm. They need to be more assertive. Preparing thoroughly may help compensate for their lack of confidence and drive at the negotiating table. This means understanding the subject matter, their interests and currencies, and their counterparts’ interests, currencies, needs, and constraints. It also means anticipating what might occur during the negotiation and having a clear idea of what they will do if various contingencies unfold. Having an assertive colleague present during negotiating sessions could also help, as people often push harder for others than for themselves, but I strongly recommend a course on assertiveness training and practice developing assertiveness skills.

Competitive negotiators look for a win-lose result— winning is everything. It would be wise for them to help their counterpart get at least a partial win as well. After all, they still win, and they also gain goodwill by allowing their counterpart to enjoy a better than expected outcome. However, competitive negotiators often want to see their counterpart lose: for them, it reinforces the idea that they have won. It is not pleasant dealing with a competitive negotiator, even if you are assertive. However, you will need to negotiate with such a person on occasion. The best you can do is to understand him, brace yourself, and try to find a win-win. He may not begrudge you a win if he wins as well, but ultimately, he is only concerned with his own interests.

Compromising negotiators, at first glance, appear reasonable. They are willing to give up something in exchange for something else, provided their counterparts do the same. It seems only fair. Some people even define negotiation as the art of compromise. However, this approach does the art of negotiating a disservice. As we will see shortly, it is the easy way out. It is far better to learn the ways of the win-win negotiator than to settle for a quick and easy partial win.

Collaborating negotiators, as you have probably guessed, are win-win negotiators. They work with their counterparts to solve their problem together by building trust, communicating openly, identifying interests, leveraging currencies, and designing options that allow them to create maximum value for all involved.

The collaborating style of negotiating is clearly the win-win approach. If we are advocating the win-win approach and learning win-win techniques, why bother with the other four styles? There are a few reasons.

• While you may be sold on the merits of win-win negotiating, your counterpart may not see it that way. You will find yourself dealing with competitive types. You need to recognize that style and know how to protect yourself.

• Even committed win-win negotiators can use other styles. Sometimes you will be expected to be competitive, or to compromise. Remember, negotiation is a game. You need to understand and play by the rules.

• No single style is good enough for all occasions. You will need to be flexible enough to adopt other styles.

• And let’s face it, there may be times when you adopt a competitive posture because you want to win as much as possible and are not concerned with how your counterpart fares. When buying a used car or negotiating disputed charges with the phone company, do you really care if the other party doesn’t make money on the deal?

Most people have a dominant or preferred style, but it may vary with the situation and the people involved. While collaboration is generally the best outcome, and avoidance and accommodation are not usually effective, there are times when each style has its own advantages.

Consider choosing an approach based on the following factors:

1. Avoiding

When the issue is trivial, it may not be worth your time. When emotions are running high, it is wise to put off negotiating until the emotions subside. However, this should be a temporary measure. Avoidance is a poor long-term strategy. If you find yourself rationalizing avoiding behavior frequently, face reality and sign up for assertiveness training.

2. Accommodating

When the issue in question is not important to you but is important to the other party, you may choose to let them have the point. This is an easy concession to make in exchange for something else later. You might ask for something on the spot in exchange for your concession. Or you might just bask in the magnanimity of letting the other person have what they want, especially if the relationship is a close one (like a marriage!).

3. Competing

In a one-off negotiation where you have no ongoing relationship with your counterpart, you may not care whether he wins or loses, you just want a win. Or in a negotiation where the only issue is price, a gain for one party means a loss for the other. The most likely result when negotiating solely on price is a partial win for both parties, but you may want your part to be as big as possible. Finally, you may find yourself negotiating in a crisis situation that requires quick, decisive action on your part.

4. Compromising

You may find yourself in a situation where time pressures require a prompt settlement, and you don’t have the time to explore win-win solutions. Or where both parties are equal in power and neither will concede much. Or where the parties accept a compromise as a temporary measure to a complex problem, and intend to pursue a more lasting settlement later—for example, a ceasefire agreement rather than a full-blown treaty. You might also compromise when neither party can propose a win-win solution and both prefer a partial win to no deal, although in such cases it would be best to put in more effort and try to come up with more imaginative options.

5. Collaborating

When both parties want a win-win and have the time and mindset to pursue it, the chance of a win-win is good. Or the issue may be too important to compromise, and failure is not an option. When a win-win is imperative, there is often a way to get it.

While collaboration is the ideal, even win-win negotiators need to use other approaches on occasion.

Another factor that could influence your choice of negotiating style is whether the negotiation is a distributive or an integrative negotiation.

In a distributive, zero sum, or fixed pie negotiation, the parties negotiate over a single issue. To use a time-worn metaphor, this is about dividing the pie, and each party wants the bigger piece. Any gain by one party comes at the expense of the other. A win-lose or partial win result is likely, and some compromise is usually necessary.

The most common form of a distributive negotiation is where the parties haggle over the price of a single item. The sole issue is the price to be paid: the buyer wants to pay less, while the seller wants to receive more. Other single issue negotiations might involve the allocation of a limited resource such as time, manpower, or use of equipment.

In a distributive negotiation you are likely to adopt a competitive approach. When both parties want more, they have to fight for it. This is especially true in a one-off negotiation, where there is no continuing relationship. In some relationships—such as a marriage or a workplace setting—you will still have a series of single issue, distributive negotiations. In such cases you will want to think twice about a competitive stance and consider tradeoffs to keep the relationship on an even keel.

In an integrative negotiation there are multiple issues. This allows for the possibility of tradeoffs, creating value, expanding the pie, and maybe even a win-win. A collaborative approach will make that win-win more likely. By introducing additional issues to a single-issue negotiation you can change it from distributive to integrative and increase the likelihood of a win-win.

In reality, most negotiations are a mix of distributive and integrative. After the parties collaborate to make the pie as big as possible and create maximum value, they stop playing nice and try to get as much as they can. When shifting from integrative (expanding the pie) to distributive mode (dividing the pie), you don’t want to seem like a Jekyll and Hyde. The transition is smoother when you create value for both parties, empathize, and have a solid rationale to justify your claims.

When two people can’t quite close the gap and reach an agreement, it is common to compromise. One person might say “Let’s just split the difference,” or “Let’s meet in the middle.” He believes this is the fair thing to do, as each party is making a sacrifice and each is getting part of what he wants. While compromise may seem fair, it is not good negotiating.

The Old Testament tells a story about two women, each claiming to be the mother of an infant. The women approached King Solomon to resolve their dispute. He suggested that they cut the baby in half, knowing that the real mother would prefer to see her child alive with someone else than dead in her own arms. Sure enough, he was right—King Solomon was known for his wisdom, after all! Imagine if the two women did agree to split the baby. That would definitely have been a lose-lose outcome, but a compromise often is.

When we compromise, both parties make a sacrifice. While each gets something, neither gets everything he wants. Compromising usually leads to a partial win at best, never a win-win.

A better way is to consider more options and try to find a win-win. Sure, it takes more effort, but we often take the easy way out and compromise far too quickly, without really trying to find a win-win solution.

Consider compromising only as a last resort. While compromise is often used to resolve difficult negotiations, it is a copout. Exhaust all efforts to collaborate on a win-win outcome before taking the easy way out. It may take time, perseverance, creativity, and a good flow of communication, but the results will be worth it.

Some years ago, my wife and I were discussing where to go for our vacation. She wanted to go to Hawaii, and I wanted to go to Kyoto. How could we resolve our differences?

1. We could go to Hawaii one year and she would be happy and I would not be, then go to Kyoto the next year and I would be happy and she would not be. Not optimal.

2. She could go to Hawaii and I could go to Kyoto. Also not optimal, possibly grounds for divorce.

3. We could meet in the middle—compromise—and we would have ended up somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. Definitely not optimal.

In the end, we understood that where we thought we wanted to go was a position. The reasons we wanted to go there reflected our interests. (Positions and interests will be covered in the next chapter.) I asked her why she wanted to go to Hawaii. She gave her reasons:

1. “I like a relaxing vacation. Kyoto is not relaxing, it is hectic, getting on the tour bus, going to a shrine, getting off the tour bus to visit the shrine, getting back on the bus to go to the next shrine, etc.”

2. “I like a tropical vacation with a beach. Kyoto is not tropical, and I don’t think it has a beach.”

3. “I like to enjoy a drink and watch the sunset. Kyoto is in the land of the rising sun, and I don’t know if it has a sunset.”

Then I gave her my reasons why I wanted to go to Kyoto:

1. “I am an art lover. Kyoto has a lot of great art. The only art in Hawaii are those carved coconut heads.”

2. “I also appreciate architecture. Kyoto has magnificent architecture, with wooden temples hundreds of years old, built without a single nail. Hawaii’s architecture is mostly uninspiring post-WWII cement block buildings.”

3. “I like a place with a sense of history. Kyoto has an exceptionally rich history.”

Having identified our interests, our task was to find a place that satisfied both of our interests to the greatest extent possible. Where could we go that was relaxing, had fabulous beaches and gorgeous sunsets, as well as a rich sense of history with lots of great art and architecture? We went to Bali, and we were both happy.

Two people can look at the same situation and interpret it differently. One sees the glass as half empty, the other as half full. One sees a risk, the other an opportunity. How you see it depends on the lens through which you view the world, or your frame.

A frame is an arbitrary reference point that influences the way a person views a situation. While people will usually adopt a frame without giving it much thought, they can be swayed to adopt another frame. This ability to shape another’s perceptions is too powerful to ignore. Consequently, a win-win negotiator thinks about how issues are framed.

You may be familiar with the story of Tom Sawyer whitewashing his Aunt Polly’s fence. One fine sunny morning, Aunt Polly assigned Tom this unpleasant chore. As Tom toiled away, other kids interrupted their play to tease him. Tom pretended not to be bothered, and told the others it wasn’t work, it was fun. After all, you can go swimming or fishing anytime, but it’s not every day you get the chance to whitewash a fence.

It wasn’t long before the other boys were begging for a turn with the brush. Tom expressed doubt as to whether he should let others share in his fun, which made them even more eager to do it. Soon, all the boys in the neighborhood were lining up for a turn, and trading their prized possessions for the privilege! Tom relaxed in the shade, enjoying his windfall while the others completed his chore.

Tom Sawyer was able to persuade others to do an unpleasant task by framing it in a positive way. The other boys adopted his frame and agreed to his proposal.

Most people feel more strongly about avoiding a loss than working for a gain. In a widely cited study, Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky found that people were motivated twice as much by the fear of a loss as by the prospect of a gain.* In other words, losing is twice as painful as winning is enjoyable. People in a loss-minimizing frame of mind will try harder and risk more to avoid the loss. You can exploit this mindset by playing to their fears, by saying, “It would be a shame to miss out on this deal after all we’ve put into it.”

People in a gain maximizing frame, on the other hand, are more conservative and more likely to accept a moderate gain than to fight hard for a more advantageous settlement. They are easier to negotiate with. The upshot of all this is that you should encourage your counterpart to adopt a gain maximizing frame. You can influence her by emphasizing what she stands to gain if you are able to reach an agreement, rather than what she may lose if you don’t. A frame emphasizing what you’re giving the other party (“We can let you have the apartment for $1,600 a month”) normally works better than one in which you’re asking them to give up something (“We’re asking $1,600 a month rent for the apartment”).

When facing a possible gain, most people become more risk averse—our desire to hold onto our gain and not lose it is stronger than our desire to try to win more. Casino operators know this. Winners usually want to hang onto their winnings and quit. Losing gamblers will usually keep playing in the hopes of overcoming their loss. This approach works for the casinos because it’s a numbers game for them—they don’t have to know the risk appetite of every guest. But in the negotiation setting, it pays to know the risk profile of your individual counterpart and frame the issues accordingly.

It is also important to know your own risk profile and frame. A negative frame leads us to be less flexible, to offer fewer and smaller concessions, and to be less satisfied with the outcome and the process. It also makes us more prone to impasse and quicker to resort to litigation.

The best negotiators think about how to frame issues to their advantage. By framing an issue or wording a proposal a certain way, you can influence the way your counterpart responds. Do you advocate a proposal based on what the other party stands to gain by doing the deal, or what he will lose by not reaching an agreement? You can also frame issues in other ways, such as fair/unfair, popular/unique, traditional/cutting edge, and so on. Just remember that the frame needs to be believable, so be sure you are able to justify it. For example, in business we don’t like to use us the word “problem”; we would rather frame it as a challenge or maybe even as an opportunity. But it would not have been believable for the Apollo 13 astronauts to say, “Houston, we have an opportunity!”

Once upon a time, our family car was nearing the end of its useful life, and my wife said to me, “We need a New Car.” That, of course, is a position. Our interest was in finding a way to meet the transportation needs of the family. A New Car would do it, but there could be other ways of addressing that need. The transportation situation had changed a lot since we got our Old Car. A new train station had opened near our home, where before there was none. Our daughter had grown up and was able to get around independently, where before we had to drive her. We now had Uber and other ride-sharing options, which did not exist previously. Times had changed, and we had to change with the times. So I proposed to give my wife and daughter a monthly Transportation Allowance that would allow all of us to get around for much less than the expense of a car, insurance, gas, parking, tolls, road tax, etc. We could save money and fully satisfy our interests, all because I was able to frame the situation in such a way that the alternative to Old Car was Transportation Allowance rather than New Car. It was sheer brilliance!

My wife did not accept my frame, and viewed having a car as non-negotiable. So we ended up getting the New Car. In negotiation as in life, you have to know when to concede.

Abraham Lincoln said, “When I’m getting ready to reason with a man, I spend one-third of my time thinking about myself and what I am going to say, and two-thirds thinking about him and what he is going to say.” How many negotiators put that much effort into thinking about the other side?

When my daughter first started to walk, she would explore everything within reach. If I went into the storage room, she would follow me and pick up screwdrivers, light bulbs, batteries, and other items not meant for toddlers. I would tell her to put those things down, they were not toys, they were dangerous, she could hurt herself, and so on. None of these reasons worked. I should have known they were doomed to fail, because from her perspective, she had no reason to agree to my demands. She was having fun, and I was asking her to stop having fun. She had nothing to gain and everything to lose.

I had to reformulate my request to make it acceptable to her. I asked her, “Would you like to close the door?” I can only imagine her thought process: “Close the door? I’ve never done that before, but I think I can do it. It sounds like fun. My dad will be so proud of me.” She immediately dropped everything, slammed the door shut, and ran off with a triumphant grin on her face. She gave me exactly what I wanted, but I had to present it to her in a way that appealed to her interests. She viewed this as a net gain for her, and so agreed to my request. There was nothing to negotiate or clarify, she could simply say yes.

I like to think I am more powerful than my daughter and can demand her compliance. By traditional measures of power such as size and strength, I am more powerful than she is. A lot of negotiators like to think this way. However, it is counterproductive. It causes resentment and harms the relationship. Wouldn’t it be better to gain someone’s willing and enthusiastic cooperation rather than her grudging compliance?

The key to reaching an agreement or resolving a conflict lies in understanding the way the other person sees things. While it is certainly important to think about what we really want and how to get it, we need to think even more about our counterpart, what he wants, and why he might agree to our request.

You are not simply making a request. You are asking the other person to make a decision—to accept your proposal or reject it. Ask yourself these questions:

• What do I want him to do? Is my request clear?

• From his perspective, why would he agree to do it?

• How will he view the consequences of doing or not doing what I ask?

This exercise should give you some new insights. Your demand must be realistic—something your counterpart could agree to. You may conclude: There’s no way he will ever agree to that! If that is your first reaction, it will probably be your counterpart’s as well. So don’t ask. Put yourself in the other party’s shoes. She won’t do anything simply because you want her to do it. She will only do things because she wants to do it. Try to understand what she wants, bearing in mind that she may not want the same things you want. Try to formulate your request so that it makes sense for your counterpart to agree.

One way to do this is by using what Roger Fisher calls a “yesable” proposition.* There are two steps to this method. First, put your request into a form where the other party can reply with a clear yes or no. We are not always clear about what we want the other person to do. If our thinking is not clear, our request will not be clear either. If our request is not clear, the other party will not have a clear choice. A confused mind always says no. Cast your request in a form that is so clear and simple that your counterpart’s choices could be to check a box marked yes or no.

Second, arrange the incentives and disincentives such that your counterpart finds it advantageous to say yes. No one is likely to agree to anything that does not leave him better off.

Give your counterpart a yesable proposition, a request phrased so she can respond immediately with either a yes or a no. If you truly understand her thinking and interests, and phrase your proposal the right way, you’ll get a yes.

The most important tool a win-win negotiator has is his attitude. A win-win negotiator is positive, optimistic, collaborative, and objective. He understands that a win-win outcome is rarely an accident, but the result of systematic application of certain principles. These principles are:

• Approach the negotiation as a problem to be resolved in collaboration with your counterpart. Do not enter a negotiation looking for ways to beat your adversary. Think win-win instead of win-lose. Look for ways to enlarge the pie so that everyone gets a bigger piece.

• Be objective. Don’t fall in love with the subject of the negotiation. Be aware of the roles of emotion and biases. Take calculated risks.

• Be positive and optimistic. Aim high. Negotiators with higher aspirations generally end up with more. Set an aggressive anchor and justify it.

• Be persistent. Continue generating options and looking for ways to create value. Remember that the reason win-win outcomes are so rare is not that it can’t be done, but that the win-win solution has not been found yet. Compromise only as a last resort.

• Keep your Plan B in mind and be prepared to exercise it. Negotiation is a voluntary process. Be prepared to walk away if you can’t get what you want on satisfactory terms. No deal is better than a bad deal.

• Treat the negotiation as a game. Learn the rules and practice the skills. Take the game seriously but not personally. Have fun and try to improve over time.

The most successful negotiators are also confident. Confidence is largely a matter of attitude. You feel ready, positive, and have high expectations. Confidence is also a function of preparation. When you are well prepared you are confident, and when you are not prepared you are not. If you are not prepared, you should not be negotiating.

Confidence is more than just a feeling or state of mind, something internal to you. It is also what the other party sees in you. It is largely a matter of perception. You can appear confident even when you may feel some uncertainty or doubt. You can project confidence by:

• Being comfortable with others and the situation (smile, be friendly and outgoing, calm and relaxed).

• Having strong body language (eye contact, handshake, posture, gestures).

• Speaking in a strong (not necessarily loud), sure, and measured voice. Being articulate and having a deep, lowpitched voice is a big plus.

• Being decisive and avoiding weak words such as maybe, kind of, I guess, um, and so on.

• Looking like a successful businessperson (clothing, grooming, accessories).

• Being enthusiastic!

In business dealings, the more confident person usually prevails. Be that person.

Most negotiators reject an offer or proposal without giving it much thought. Perhaps they respond immediately with their own counter-offer. They feel they are projecting confidence and strength by showing their conviction about what they want and don’t want. They fear that any wavering on their part will be seen as a sign of weakness by the other party. And rejecting a proposal allows them to feel in control: they are in the driver’s seat and won’t be led around by anyone.

Win-win negotiators know better. An immediate rejection is insulting. It shows a lack of respect. That offer is a product— and an extension—of the other party. You do not help your case by abruptly rejecting your counterpart. By pausing to consider an offer, you show you are taking both the offer and the other person seriously.

Also, by thinking about your counterpart’s offer, you just might find some merit in it. You may find some common ground that you would otherwise miss with an out-of-hand rejection. After considering the offer, explain what you like about it and what you don’t like. Finding even a shred of value in his offer and working with it will place you in higher regard with your counterpart than if you had rejected his offer completely. Remember, win-win solutions depend on collaboration and joint problem solving, not on prevailing in a battle of wills.

By rejecting an offer, you are saying “I don’t like your idea; I want to do it my way.” But by considering their offer, focusing on an element that you agree with, and building on it, you can still end up in a place that’s acceptable to you—but they think it was their idea! This is the essence of the old saying that diplomacy (which is really negotiation) is the art of letting the other guy have your way.

Finally, give a reason why you don’t like the offer. People like to know why. It makes your rejection easier to accept. It also helps your counterpart understand your needs and interests, improving the likelihood of a win-win solution.

While we hear much talk about the coveted win-win outcome, the fact is this result is not common. There are several factors which make a win-win outcome more likely:*

• Focus on interests rather than positions

A position is what you say (and perhaps really believe) you want, while an interest is what you truly need from the negotiation. It is not always easy to identify our own true interests, let alone our counterpart’s. What we think we want may not be what we really need. Sometimes, we have to think out of the box to see the difference. And you may also learn that your counterpart has no idea what his interests are. Identifying interests—yours and theirs—and addressing those, rather than positions, is a key to negotiating win-win agreements.

• Know the currencies

A currency is anything of value, tangible (money, goods) or intangible (ego, peace of mind, branding), that can be exchanged in a negotiation. Currencies are sometimes hard to identify. If we do not value a certain asset that we possess, we may not realize that our counterpart finds value in it. We may not even be aware that it exists. Understanding the currencies that are available helps us create win-win outcomes.

• Negotiate multiple issues and create multiple options

An option is a possible solution to your negotiation problem. An option is also a package of currencies. There may be many potential solutions to a negotiation. We may only think of one. Or we may think of a few, decide one is the best, and not realize that there may be even better ones out there. The more options we can generate, the more likely we will find one that presents a win-win solution. But if you are negotiating a single issue, such as price, you are setting yourself up for a win-lose or partial win outcome.

• Use fair and objective standards

You need to convince your counterpart (and help her convince her stakeholders) that your proposal has merit. Having a sound standard to measure your proposal against can help you persuade her of the merits. This standard could be a competitive price, precedent, index, industry practice, or some other benchmark.

• Good communication and sharing information

Negotiation is a form of persuasive communication. Most negotiators are reluctant to share information for fear of giving the other party an advantage. This makes it harder for them to help you solve your problem. While some information should not be divulged, sharing information about interests is a key to a win-win.

• Good relationship based on credibility and trust

In business relationships, trust is important in fostering communication and streamlining the negotiation process. A poor relationship or lack of trust is not insurmountable, but it makes negotiating much more challenging.

• Creative thinking

The essence of creativity is making connections between things or ideas, and understanding how they relate to one another. Creative negotiators recognize patterns and know when to follow them and when to break them. Precedents, accepted practices, norms, and other patterns provide us with shortcuts. We follow the pattern and it makes our life easier. At least it does most of the time. However, if you do the things other people do (follow the pattern), you will get the results other people get. If you want something better—such as a win-win—you need to do things differently. Average negotiators come up with obvious solutions. Win-win negotiators think creatively.

We have just glossed over some key concepts in negotiation: positions, interests, currencies, and options. We will discuss them in detail in the next chapter.

* Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263–291, March 1979 and subsequent work.

* I first encountered the yesable proposition in Professor Roger Fisher’s book International Conflict for Beginners (1969). In Fisher’s metaphor, it is not enough to let them know there are carrots in the barn (step two); you must first show them the barn door (step one).

* Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes (1981).