Macon, Georgia, 1848

THERE WERE ONLY A FEW DAYS LEFT before Christmas, as a young black slave named William Craft hurried home through the dusk to the cottage he shared with his wife, Ellen. In the pocket of his coat he felt the pair of dark eyeglasses he’d bought moments before. Slaves weren’t supposed to buy such things without their master’s permission, but some storekeepers were ready to take a slave’s money and not ask too many questions.

For weeks now, William had been buying pieces of clothing one at a time — a shirt here, a hat there, all at different stores so as not to attract too much attention. The green glasses were the finishing touch on a plan, a bold and dangerous scheme William and Ellen had worked out together: their bid for freedom.

William and Ellen had always known they were luckier than many slaves. Ellen worked in her mistress’ house as a lady’s maid. William’s master had paid to train him as a carpenter and then hired him out, taking most of William’s pay but letting him keep a little for himself. Life was better for them than for the slaves on a cotton plantation — theirs was hard, back-breaking work, never far from an overseer’s watchful eye and sharp whip.

Still, they had longed for freedom. William was tired of working hard only to hand over his wages to someone else. And Ellen could never shake the fear that all they had could be snatched away. If either of their masters needed money, she or William could be sold and they would never see each other again. Worst of all, any children they might have could be taken from them. William had watched helplessly while his parents were sold at an auction to the highest bidder — and he felt the same anger and sadness whenever he remembered. Ellen had been taken from her mother when she was 11, and now she couldn’t bear the thought of raising a child to be someone’s slave. At first they had put off getting married, hoping to escape and marry once they were free.

Other slaves had done it. They’d followed the Underground Railroad — which wasn’t a railroad at all, but a long line of hiding places and secret helpers that ran from the southern slave states through the free north, all the way to Canada. Some slaves had even made a desperate run for it, following the North Star at night, hiding in woods and swamps during the day. With luck, they stumbled upon a friendly person who could tell them the way to the next safe house, or “station” along the railroad.

But Ellen and William wanted to come up with a plan before they made their move. Whenever they were alone they whispered together about all kinds of schemes, yet every one had its problems.

“A train or boat would get us out of Georgia the quickest. We could save for the fare,” Ellen ventured.

William shook his head. “Not without permission from our masters. We can’t even walk the roads without that. Any white person could stop us and ask for our passes, to show we had a right to be there. And then what?” He paused and added, “They’d send slave catchers after us, that’s what.”

Ellen was silent. They both knew about professional slave hunters. The way they tracked down runaways — on horseback with guns and dogs — reminded William of a fox hunt. He shuddered as he imagined himself and Ellen being dragged back to slavery. And not to their old jobs, either. They’d be punished as a lesson to other slaves — separated and sold “down the river” to a much harder life on a plantation.

The more they talked, the more impossible it seemed to make it across the slave states to freedom — a journey of nearly a thousand miles. Ellen and William asked for their masters’ permission to marry, and they tried to make the best of it. But they never forgot their dream, and kept their eyes open for the smallest hope of escape.

Mending a drawer in his workshop one December afternoon, William puzzled over the problems that stood in their way. Slaves couldn’t get on a train or boat without permission. As he sanded, he pictured Ellen. She was so fair-skinned; she had a white father, after all. A bold plan began to form in William’s mind. What if Ellen pretended to be white, while William traveled as her slave?

But no, he knew a southern lady would never travel alone with a male servant. Then a sudden idea made his hand pause on the wood. Ellen could disguise herself as a white man. They could escape in daylight, under the noses of the slaveholders themselves! They’d travel first-class to Philadelphia — in the free state of Pennsylvania — and from there through the northern states to Canada.

It was risky, he thought, but so unexpected that it might have a chance. He knew that some slaveholders gave their favorite slaves a few days’ holiday around Christmas. If he and Ellen could get time off, it would give them a head start before they were missed.

That night William described his plan to Ellen. She was too shocked to speak at first. How could she keep up a disguise like that for hundreds of miles across the slave states? No, thought Ellen, it was too crazy. Then she pictured the life that lay before her if she did nothing — years of work without anything to call their own, not even their own bodies. And always the fear of losing her husband, her future children to the auction block. She looked at William and nodded — she would take the risk.

William began to buy as many pieces of her disguise as he could, a little at a time. Ellen was extra careful to please her mistress before she asked for a pass to be away for a few days, and the cabinetmaker gave William a pass without too much fuss. They hurried home to show each other their passes, but neither could read them — it was illegal to teach slaves to read. They’d have to trust that the passes said what they hoped.

So far all the pieces were falling into place. But as the day of escape drew closer, Ellen began to notice flaws in their plan. “William, any traveling gentleman would sign his name to register at a hotel — and I can’t write!”

William slumped in his chair — he hadn’t thought of that. Ellen paced the cottage floor anxiously. Then her face lit up. “I think I have it — I’ll bind up my right hand in a sling, and ask the innkeeper to sign for me.”

Then, glimpsing herself in a mirror, she frowned — her face was too smooth to convince anyone that she was a man! She pulled some cloth out of her sewing box and wound it into a bundle. Wrapping it around her chin with a handkerchief, she tied the ends over her head.

“As if I had a bad toothache,” she explained, turning to show William. He agreed it could work. And it would give her an excuse to avoid chatting with other travelers — the less she had to talk, the better.

Four more nights passed as they stayed up late, talking over their plan in the darkness. The sling and handkerchief gave William more ideas. If Ellen acted sick and lost in her thoughts, people wouldn’t bother her. Like many slave owners, she’d count on her slave to fetch and carry for her — and answer questions from any nosy fellow travelers. And in only a few days, they could be free!

The moment they had so eagerly awaited was almost at hand. Ellen’s costume was nearly finished. Whatever William hadn’t been able to buy, Ellen had sewn herself in her moments alone. The evening before their escape, William brought home the pair of glasses that would complete the picture. The dark lenses would hide any fear in Ellen’s eyes. They both knew she would have to sit surrounded by white men — and slave owners — wherever they traveled.

Just before dawn, William cut off Ellen’s long hair. With trembling hands she slipped on her dark suit, cloak, and hat, then the high-heeled boots that would make her look taller. As she stood leaning on a cane, with one arm in a sling and bandages on her face, William took a long look at her. He smiled and shook his head in disbelief — she looked so much like a sickly white gentleman he was almost convinced himself!

It was time to go. They blew out the candles, and a sudden noise made them jump — was someone outside? Holding hands, they peeked out the cottage door. Everything was still. Silently they tiptoed outside and stood breathless, looking at each other. From now on they would be traveling apart most of the time — blacks did not sit next to whites on trains and in boats. Without speaking they clasped hands, and then left in different directions for the rail station. William headed for the railcar reserved for blacks, and Ellen, leaning on her cane, limped to the first-class carriage. In her new identity as a young planter called Mr. Johnson, she bought a ticket for herself and one slave for Savannah — their first stop. There was no going back now.

Inside the carriage, Ellen took a window seat and stared outside. Sit still, she told herself. Don’t attract attention. As the train slowly chugged away from the station, she glanced around the carriage — and froze. Mr. Cray, an old friend of her master who had known her since she was a child, had sat next to her while she was looking the other way. Ellen fought the urge to bolt, and turned slowly back toward the window. Why had he said nothing? Maybe he hadn’t recognized her yet. If he strikes up a conversation, thought Ellen, he’ll be sure to know my voice. Desperate, she decided to pretend to be deaf.

Mr. Cray soon turned to her and said politely, “It is a very fine morning, sir.”

Ellen kept staring out the window. Mr. Cray repeated his greeting, but Ellen did not move. A passenger nearby laughed. Annoyed, Mr. Cray said, “I will make him hear,” then, very loudly, “IT IS A VERY FINE MORNING, SIR.”

Ellen turned her head as if she had only just heard him, bowed politely and said, “Yes.” Then she turned back to the window.

“It is a great hardship to be deaf,” another passenger remarked.

Mr. Cray nodded. “I will not trouble the gentleman anymore.”

Ellen began to breathe more easily — he hadn’t recognized her! Her disguise had passed a difficult test, but she realized more than ever how wary she must be.

The train pulled into Savannah early in the evening. William was waiting for Ellen outside her carriage, and they headed next for a steamboat bound for Charleston. Once on board, Ellen slipped into her room and shut the door. What a relief to be alone! But some of the passengers grumbled to William that this was strange. Why wasn’t his young master staying up and being friendly?

William hurried to Ellen’s room and told her about the reaction. They couldn’t afford to do anything suspicious. But she couldn’t very well play cards and smoke cigars without giving herself away! Ellen thought quickly: William could go heat up the bundle of medicine for her face on the stove in the gentlemen’s saloon, to make it look as if his master was ill and going to bed early. The men in the saloon complained loudly about the smell the hot herbs made and sent William away. But they seemed convinced that his master must be pretty sick!

Once Ellen had turned in, William went on deck and asked the steward where he could sleep. The steward shook his head — no beds for black passengers, slave or free. William’s heart sank, but he said nothing. As expected, his journey was turning out to be very different from Ellen’s! Weary, he paced the deck for a while, then found some cotton bags in a warm spot near the smokestack and sat there until morning.

At breakfast, the ship’s captain invited Ellen to sit at his table, and he asked politely about her health. William stood nearby to cut Ellen’s food, since her arm was in a sling. When he stepped out for a moment, the captain gave Ellen some friendly advice: “You have a very attentive boy, sir; but you had better watch him like a hawk when you get on to the North.”

A slave dealer sitting nearby agreed that William would probably make a run for it, and offered to buy him then and there. “No,” Ellen answered carefully. “I cannot get on well without him.”

Later up on deck a young southern officer warned Ellen that she would spoil her slave by saying “thank you” to him. “The only way to keep him in his place,” he declared, “is to storm at him like thunder, and keep him trembling like a leaf.”

I feel sorry for his slaves, thought Ellen. But from then on she remembered not to be so nice to William in front of people.

By now the boat had reached the wharf at Charleston, but when Ellen saw the crowd waiting for the steamer she shrank back. All those people — someone might recognize William. Or what if their owners already knew they had escaped and had sent someone to arrest them? She led William back to her cabin, where they waited nervously until every other passenger had left. At the last minute they stepped onto the empty wharf, and William ordered a carriage to take them to the best hotel.

When the innkeeper saw Ellen in her fine clothes and sling he pushed William aside and showed Ellen to one of the best rooms. Ellen would have loved to rest, but she knew the curious servants were expecting her downstairs for dinner. While she was led to the elegant dining room, William was handed a plate of food and sent to the kitchen to eat. Looking down, he saw that the plate was broken and that his knife and fork were rusty. William sighed but wasn’t much surprised. He ate quickly and returned to wait on his “master,” not wanting to leave Ellen alone for too long. As he entered the dining room he tried not to smile — three servants were already fussing over Ellen, each hoping for a tip from such a fine gentleman.

Ellen and William had planned to take a steamboat from Charleston to Philadelphia — and freedom! But at the inn Ellen learned that the steamer didn’t run during winter. Their only choice now was the Overland Mail Route. They could take a steamer to Wilmington, North Carolina, and catch the mail train there. Ellen tried to hide her disappointment. This was a longer route — and the longer their journey, the more chances of being caught.

There was no choice but to press on. The next day, William and Ellen headed for the crowded ticket office, where Ellen asked for two tickets to Philadelphia. The mean-looking man behind the counter looked up and stared at William suspiciously. Then he asked Ellen to register her name and the name of her slave in his book.

Ellen ignored his glare. She pointed to the sling on her arm. “Would you kindly sign for me, please?” The man shook his head and stubbornly stuck his hands in his pockets. William glanced around and saw that people had stopped to stare at them. The last thing they wanted was more attention.

Stay calm, Ellen told herself, and she was thankful for the dark glasses that hid her eyes.

She was about to speak again when she heard a voice call “Mr. Johnson!” Ellen spun around. The young officer she had met on the last steamer — the one who had told her not to be so polite to her slave — was pushing through the crowd. He patted her on the back and cheerfully told the ticket seller, “I know his kin like a book.”

At this the captain of the Wilmington steamboat, who had been watching silently nearby, spoke up. “I’ll register the gentleman’s name,” he declared, no doubt realizing that he was about to lose a passenger, “and take the responsibility upon myself.”

Once the steamer was on its way, the captain took Ellen aside to explain. They were always very strict at Charleston — you never knew when a sympathetic white person might try to help a slave run away by pretending to be his master.

“I suppose so,” Ellen said casually.

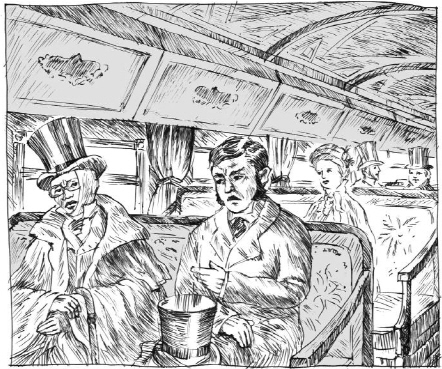

The next day they switched to a train for Baltimore. Once again, William rode in a separate car while Ellen sat in a first-class carriage, this time with a gentleman from Virginia and his two daughters.

“What seems to be the matter with you, sir?” the man asked her in a kindly tone.

“Rheumatism,” Ellen replied. He nodded and insisted that Ellen lie down.

Good idea, thought Ellen, the less chatting the better. The daughters made a pillow for her with their shawls and covered her with a cloak. While Ellen pretended to sleep, she heard one of them sigh and whisper, “Papa, he seems to be a very nice young gentleman.” Her sister added, “I never felt so much for a gentleman in my life!” When Ellen told William about it he laughed. They had certainly fallen in love with the wrong man!

Before leaving the train, the girls’ father handed Ellen a recipe — his “sure cure” for rheumatism. Ellen didn’t dare pretend to read it. What if she held it the wrong way? So she thanked him and tucked it in her pocket.

It was Christmas Eve as the train slowed to its stop at Baltimore, where they would switch to a train for Philadelphia. This was the last “slave port” on their journey, and Ellen felt more nervous than ever. We’re so close now, she told herself. Only one more night to get through. She and William knew that people kept a keen eye out for runaways in Baltimore, to stop them from escaping into the free state of Pennsylvania. They could lose everything just in sight of their goal.

As usual, William helped Ellen into the first-class carriage when they switched trains. He was about to board his own car when he felt a tap on his shoulder. He turned to face an officer, who asked sharply, “Where are you going, boy?”

“To Philadelphia, sir,” William answered humbly, “with my master — he’s in the next carriage.”

“Well, you had better get him, and be quick about it, because the train will soon be starting. It is against the rules to let any man take a slave past here, unless he can prove that he has a right to take him along.” He then brushed past William and moved down the platform.

William stood frozen for a moment, not knowing what to do. Then he stepped into the first-class carriage and saw Ellen sitting alone. She looked up at him and smiled. He knew what she was thinking: they would be free by dawn the next morning. William struggled to keep his voice steady as he told her the bad news. Ellen’s face fell. To be caught this close to freedom! She looked searchingly at William, but he was speechless. What choice did they have? Run for it now? They would be caught before they were outside the station. There was only one way — they would have to brave it out to the end.

Ellen led William to the station office and asked for the person in charge. A uniformed man stepped forward. Ellen felt his sharp eyes upon her.

“Do you wish to see me, sir?” she asked. The officer told her no one could take a slave to Philadelphia unless he could prove he was the rightful owner.

“Why is that?” Ellen demanded. The firmness in her voice surprised William. The officer explained that if someone posing as a slave owner passed through with a runaway, the real master could demand to be paid for his property.

This exchange began to attract the attention of other passengers. A few shook their heads and someone said that this was no way to treat an invalid gentleman. The officer, seeing that Ellen had the crowd’s sympathy, offered a compromise.

“Is there any gentleman in Baltimore who could be brought here to vouch for you?”

“No,” said Ellen. “I bought tickets in Charleston to pass us through to Philadelphia, and therefore you have no right to detain us here.”

“Well, sir, right or no right, we shan’t let you go,” was the cold reply.

A few moments of silence followed. Ellen and William looked at each other but were afraid to speak, in case they made a mistake that would show who they really were. They knew the officers could throw them in jail, and then it would only be a matter of time before their real identities were discovered and they were driven back to slavery. A wrong word now would be fatal.

Just then the conductor of the train they had left stepped in. He commented that they had indeed come on his train, and he left the room. The bell rang to signal their train’s departure, and the sudden noise made everyone jump — all eyes fixed more keenly on them. Soon it would be too late.

The officer ran his fingers through his hair, and finally said, “I really don’t know what to do; I calculate it is all right.” He let them pass, grumbling, “As he is not well, it is a pity to stop him here.”

Ellen thanked him and hobbled as quickly as she could with her cane toward her carriage. William leapt into his own railcar just as the train was leaving the platform.

Before long the train pulled to a halt alongside a river, where a ferry boat would carry the passengers to a train on the other side. When a porter asked Ellen to leave her seat and head for the ferry, she stood up and looked around for William. He always appeared as soon as the train stopped to “assist” her. Now he was nowhere in sight. On the platform she asked the conductor if he had seen her slave.

“No, sir,” he said. “I haven’t seen anything of him for some time.” He added slyly, “I have no doubt he has run away, and is in Philadelphia, free, long before now.”

Her panic rising, Ellen asked if he would look for William. “I am not a slave hunter,” he huffed, and left her.

It was cold, dark, and raining as Ellen stood alone. Her mind started racing with possibilities — had William been left behind in Baltimore... or been kidnapped by slave catchers? Then with horror she remembered — she had no money. They had left it all with William because pickpockets wouldn’t bother stealing from a slave. She looked down at the tickets in her hand, their tickets to freedom. They seemed worthless now that she had lost William.

Her time was up — everyone else had boarded the ferry. There’s no going back, she thought. All she could do was press on to Philadelphia, and hope that someday she would find him.

William was closer than Ellen thought. They had been traveling day and night and sleeping very little. Fear and excitement had kept them awake until now. But finally, within hours of Philadelphia, William had nodded off. Sound asleep, he was tumbled out with the luggage onto a baggage boat.

A guard later found William and shook him awake. “Your master is scared half to death about you,” he said.

William sat up, frightened — had something happened to Ellen? “Why?” he gasped.

“He thinks you have run away from him,” the guard replied.

Relieved, William hurried to Ellen to let her know what had happened. The conductor and the guard laughed as if it were all a great joke. Then the guard took William aside and told him he really should run away once they got to Philadelphia.

“No, sir,” William replied. “I shall never run away from such a good master.” The guard was stunned, but William wasn’t going to let anyone in on their secret — not yet.

Back in his own railcar, another passenger quietly told William of a boarding house in Philadelphia where he would be safe if he ran away. A station on the Underground Railroad! William thanked him, but did not say any more.

Just before dawn, William stuck his head out the train window. He could see flickering lights ahead in the distance. Then he heard a passenger say to his friend, “Wake up... we are at Philadelphia!” William felt as if a heavy burden had slipped off his back. He stared at the glittering city as the train sped on, and the sight made him lightheaded.

It was Christmas Day. Before the train had fully stopped, William was already running to Ellen’s carriage. They hurried into a cab and William gave the driver the address of the boarding house he had heard about.

“Thank God, William, we are safe!” Ellen exclaimed, and broke into sobs. After pretending for so long, she felt drained. She leaned heavily on William as they stepped out of the cab and climbed the stairs to their room.

Ellen rested a while, then took off her disguise and changed into the women’s clothing she had packed. She and William walked into the sitting room and asked to see the landlord. The man was confused. What happened to the young cotton planter he had seen arrive?

“But where is your master?” he asked William. William pointed to Ellen. “I’m not joking,” the landlord replied, becoming annoyed.

It took some time to convince him of who they were! In the end, the innkeeper sent for some antislavery friends who could help them decide what to do next. William and Ellen had planned to go to Canada, following the Underground Railroad further north. But their new friends warned them that December in Canada would be much colder than they were used to in Georgia. They would face a hard first winter in an unfamiliar place.

But staying in Philadelphia wouldn’t be safe either — slave catchers sometimes kidnapped runaways there, even though it was in a free state. Boston might be a better choice. Most people there were so against slavery that slave hunters didn’t dare try. And so it was decided. Ellen and William stayed with a Quaker family until they were ready to leave for Boston, and a new life.

Even in Boston, the Crafts did not feel safe for long, however. Two years later, the Fugitive Slave Bill was passed. Slave catchers could now legally follow runaways into the free states and bring them back. With the help of Underground Railroad workers, Ellen and William escaped a warrant for their arrest and fled to Halifax, where they boarded a ship for England.