Perhaps it’s still unclear how I ended up in there. It must have been something more than a pimple. I didn’t mention that I’d never seen that doctor before, that he decided to put me away after only fifteen minutes. Twenty, maybe. What about me was so deranged that in less than half an hour a doctor would pack me off to the nuthouse? He tricked me, though: a couple of weeks. It was closer to two years. I was eighteen.

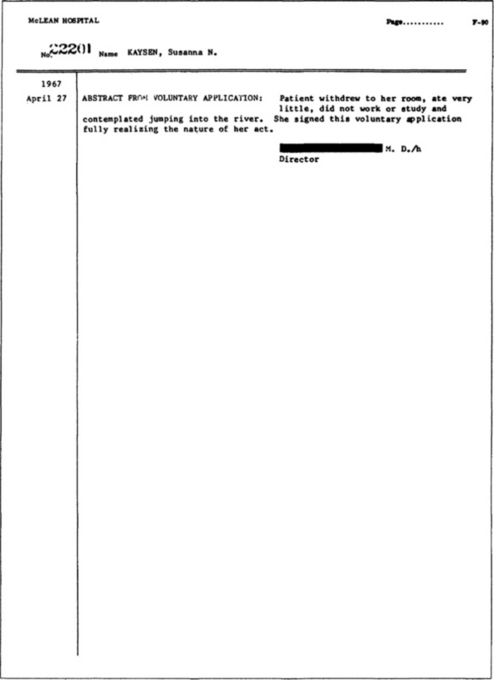

I signed myself in. I had to, because I was of age. It was that or a court order, though they could never have gotten a court order against me. I didn’t know that, so I signed myself in.

I wasn’t a danger to society. Was I a danger to myself? The fifty aspirin—but I’ve explained them. They were metaphorical. I wanted to get rid of a certain aspect of my character. I was performing a kind of self-abortion with those aspirin. It worked for a while. Then it stopped; but I had no heart to try again.

Take it from his point of view. It was 1967. Even in lives like his, professional lives lived out in the suburbs behind shrubbery, there was a strange undertow, a tug from the other world—the drifting, drugged-out, no-last-name youth universe—that knocked people off balance. One could call it “threatening,” to use his language. What are these kids doing? And then one of them walks into his office wearing a skirt the size of a napkin, with a mottled chin and speaking in monosyllables. Doped up, he figures. He looks again at the name jotted on the notepad in front of him. Didn’t he meet her parents at a party two years ago? Harvard faculty—or was it MIT? Her boots are worn down but her coat’s a good one. It’s a mean world out there, as Lisa would say. He can’t in good conscience send her back into it, to become flotsam on the subsocietal tide that washes up now and then in his office, depositing others like her. A form of preventive medicine.

Am I being too kind to him? A few years ago I read he’d been accused of sexual harassment by a former patient. But that’s been happening a lot these days, it’s become fashionable to accuse doctors. Maybe it was just too early in the morning for him as well as for me, and he couldn’t think of what else to do. Maybe, most likely, he was just covering his ass.

My point of view is harder to explain. I went. First I went to his office, then I got into the taxi, then I walked up the stone steps to the Administration Building of McLean Hospital, and, if I remember correctly, sat in a chair for fifteen minutes waiting to sign my freedom away.

Several preconditions are necessary if you are going to do such a thing.

I was having a problem with patterns. Oriental rugs, tile floors, printed curtains, things like that. Supermarkets were especially bad, because of the long, hypnotic checkerboard aisles. When I looked at these things, I saw other things within them. That sounds as though I was hallucinating, and I wasn’t. I knew I was looking at a floor or a curtain. But all patterns seemed to contain potential representations, which in a dizzying array would flicker briefly to life. That could be … a forest, a flock of birds, my second-grade class picture. Well, it wasn’t—it was a rug, or whatever it was, but my glimpses of the other things it might be were exhausting. Reality was getting too dense.

Something also was happening to my perceptions of people. When I looked at someone’s face, I often did not maintain an unbroken connection to the concept of a face. Once you start parsing a face, it’s a peculiar item: squishy, pointy, with lots of air vents and wet spots. This was the reverse of my problem with patterns. Instead of seeing too much meaning, I didn’t see any meaning.

But I wasn’t simply going nuts, tumbling down a shaft into Wonderland. It was my misfortune—or salvation—to be at all times perfectly conscious of my misperceptions of reality. I never “believed” anything I saw or thought I saw. Not only that, I correctly understood each new weird activity.

Now, I would say to myself, you are feeling alienated from people and unlike other people, therefore you are projecting your discomfort onto them. When you look at a face, you see a blob of rubber because you are worried that your face is a blob of rubber.

This clarity made me able to behave normally, which posed some interesting questions. Was everybody seeing this stuff and acting as though they weren’t? Was insanity just a matter of dropping the act? If some people didn’t see these things, what was the matter with them? Were they blind or something? These questions had me unsettled.

Something had been peeled back, a covering or shell that works to protect us. I couldn’t decide whether the covering was something on me or something attached to every thing in the world. It didn’t matter, really; wherever it had been, it wasn’t there anymore.

And this was the main precondition, that anything might be something else. Once I’d accepted that, it followed that I might be mad, or that someone might think me mad. How could I say for certain that I wasn’t, if I couldn’t say for certain that a curtain wasn’t a mountain range?

I have to admit, though, that I knew I wasn’t mad.

It was a different precondition that tipped the balance: the state of contrariety. My ambition was to negate. The world, whether dense or hollow, provoked only my negations. When I was supposed to be awake, I was asleep; when I was supposed to speak, I was silent; when a pleasure offered itself to me, I avoided it. My hunger, my thirst, my loneliness and boredom and fear were all weapons aimed at my enemy, the world. They didn’t matter a whit to the world, of course, and they tormented me, but I got a gruesome satisfaction from my sufferings. They proved my existence. All my integrity seemed to lie in saying No.

So the opportunity to be incarcerated was just too good to resist. It was a very big No—the biggest No this side of suicide.

Perverse reasoning. But back of that perversity, I knew I wasn’t mad and that they wouldn’t keep me there, locked up in a loony bin.