II

The Bookshelf

‘All a long summer holiday I kept my secret, as I believed: I did not want anybody to know that I could read. I suppose I half consciously realised even then that this was the dangerous. moment,. I was safe, so long as I could not read – the wheels had not begun to turn, but now the future stood around on bookshelves everywhere!

Graham Greene

The Lost Childhood

1951

The Silent Minaret

AFTER DINNER, FRANCES INVITES KAGISO to sit out on the roof for a while. “It’s only a makeshift affair out there,” she confesses, as she leads the way through the open window, “but in this heat, it provides a pleasant enough escape from a stuffy London flat.”

Once outside, Kagiso walks over to the low wall at the front end of the building and leans out over the bustling street below: a constant stream of commuters still pouring out of the station; the increasingly animated revellers who have spilled out of the pub on the corner and taken over the pavement; a group of kids on skateboards practising routines under a giant, brightly coloured mural across the road; the incongruous bird-like couple outside the station – she in a high-necked frilly white blouse, he sporting a comb-over and black dinner jacket with velvet lapel – anxiously expecting their lift. And all the while the continuous coming and going of buses in the terminus.

He turns around. The image of Frances sitting in the front seat of a sports car, the letters GTi in neon green on the headrest, makes him chuckle.

“Where’s the rest of it?” he asks.

She laughs too. “Issa dragged this up here last summer. He’d ripped it out of an abandoned car that had been down there for weeks. He intended going back for the other seat the next night, but by then the car had been towed. So he got that deck chair instead.”

Kagiso unfolds the chair next to the upturned crate on which Frances has balanced their glasses. He leans back into the chair and throws his head up to the sky. Not the mass of stars he’d been expecting. Not the chirping of crickets, which as a boy he took for the sound of twinkling stars.

“Light pollution,” Frances explains. “In a big city like this, only the brightest ones shine through.”

It occurs to him that he is now in the northern hemisphere once more. “Which is the North Star? Do you know?” he asks, while making a mental note to check the direction in which water spins down the drainpipe. He forgot to do so during a brief visit to DC.

“I’m afraid I don’t and isn’t that shameful? Issa asked me that very question when we were out here once. He was reading about the first European explorations down the west coast of Africa. For centuries, European sailors were terrified at the thought of crossing the equator because they’d lose sight of the North Star if they did. I didn’t understand why that was such a terrifying prospect until he explained that they used to navigate by it and so would have wanted it constantly in their sights.

“Anyway, I expect you probably know all this stuff, but I found it very interesting and we pledged to locate it but never did. In my case,” she shrugs reaching for her glass, “too much sitting around to do.”

Kagiso smiles as he watches her recline. She must be the same age as his grandmother, he thinks, yet she seems so much younger. Though more frail and with none of that big African sturdiness about her, her eyes retain a mischievous and enthusiastic sparkle.

“I remember the first time I brought him up here. It was to see the minaret,” she recalls, tilting her head towards it.

Minaret? Kagiso puzzles, then quickly scans the skyline for clues. I haven’t heard a mosque.

Then, suddenly, there it is, right in front of him, as though it had just stepped out from the shadows.

‘The Silent Minaret,’ he used to call it.

At home, minarets declare God’s greatness five times a day, but here they stand silent, like blacked – out lighthouses.

Kagiso returns to the low wall. From here he can only see the small domed enclosure at the top of the minaret with its windowless pointed arched openings from where traditionally the muezzin would call azaan:

Allah-u-akbar, Allah-u-akbar

Allah-u-akbar, Allah-u-akbar

Ashadu an la illaha illAllah

Ashadu an la illaha illAllah

Ashadu anna Muhammad ar Rasool Allah

Ashadu anna Muhammad ar Rasool Allah

Hayya alas Salat...

The railway bridge and a criss-cross of overhead electricity cables obscure the rest of the building.

“Another night, he told me about mosques and minarets: the one at the bottom of your road in Johannesburg, the one you grew up under, as he so quaintly put it. And the white mosque in the city centre reflected in the glass building across the road. The mosque in Durban sounded impressive too.”

“I only have vague memories of Durban,” Kagiso interrupts with a faraway stare. “I remember the journey more than I do the place.” He turns to face her, leaning with his back against the wall. She doesn’t seem to mind the interruption, so he continues. “Issa and I went there secretly one weekend. We’d told our mothers we were going hiking with friends in the Eastern Transvaal as it was called then, but we jumped into a taxi to Durban instead.”

“Were you found out?”

“No. But that was down to Issa’s cunning.”

“Why Durban?”

“Oh,” he sighs, “One of his quests. I just tagged along to lend authenticity to the lie.”

“Did he find what he was searching for?”

He shakes his head. “No.”

“Did you see the mosque?”

“May have,” he shrugs. “We went to so many places, I really can’t recall. Wish I’d paid more attention... Why? What did he say about it?”

“That it was the largest mosque in the southern hemisphere. That it stands so close to the Catholic cathedral that from certain angles the two buildings almost seem one. I rather liked the sound of that.”

Yes Frances, imagine that, a sky that echoes simultaneously with azaan and the Angelus.

She tried:

Allah-u-akbar, Allah-u-akbar

The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary

Allah-u-akbar, Allah-u-akbar

And she conceived of the Holy Spirit

Ashadu an la illaha illAllah

Hail Mary, full of grace

The Lord is with thee;

Ashadu an la illaha illAllah

Blessed art thou amongst women

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb,

Jesus

Ashadu anna Muhammad ar Rasool Allah

Ashadu anna Muhammad ar Rasool Allah

Holy Mary!

Mother of God,

Pray for us sinners, now,

And at the hour of our death.

Amen

“It all suggested such pictures to my mind, such sounds to my ears. I can’t think of such a place or imagine such a mingling of sounds here. That would need to be nurtured with love and respect, not battering rams and riot gear...

“He spoke of the gigantic minaret of the Great Mosque at Samara, for centuries the world’s largest, with its staircase that winds around the outside. He brought me up a picture of that one a few days later. Huge, it was. I’d never seen anything like it.

“The highest minaret in Casablanca. That was impressive too. It has a laser at the top that beams across the Sahara in the direction of Mecca. I often sit here at night and try to imagine what that must look like – a green laser beaming across a clear desert sky.

“And my favourite, the Issa Minaret, like his name, in Damascus, where the faithful expect the Messiah to appear on the Day of Judgement.”

The church-like mosque used to be the Roman temple of Jupiter, then the Basilica of St John. It’s where the head of John the Baptist is buried, a holy place for both Muslims and Christians.

“I’ve thought about that one often since. I’d never heard of it. I wouldn’t have minded seeing it. Such a link.” A real cathemosdraquel, she thinks.

“The oldest minaret in the world is in Tunisia, and the oldest mosque in Britain is in Woking, would you believe,” she says, rising from her seat to join him at the wall. “And the largest mosque in north London is in Finsbury Park. Look at it! I’m certain it used to be lit up before. You can’t see the building itself from up here, but it’s all boarded up now. Shut down, like a shipyard, because of the threat it poses.” She shakes her head. “Shameful. Just shameful, while all the time we are the ones fighting our second war.”

Remembering Hide and Seek

TONIGHT, SLEEP DOES NOT BESTOW herself freely. From the mattress, he looks across to where the shiny knob of the desk drawer plays with light from the street. He crawls two paces on his knees across the floor, takes the yellowing childhood photograph from the drawer and returns to the mattress to study it. Lying awake, his eyes have adjusted to the darkness and there is no need to turn on the light.

When they were little boys there was sometimes the novelty of playing hide and seek indoors, with their mothers. With each game, their hiding places grew more and more elaborate: in Ma Vasinthe’s secret bathroom behind the built-in wardrobes in her bedroom; behind the geyser in the roof. Once Ma Gloria even took them to hide in the neighbour’s kitchen, where they ate cakes and biscuits while they waited for Ma Vasinthe to find them. Ma Gloria had thrown them over the back wall, before jumping over the wall herself and spraining her ankle.

Wherever they hid, Ma Vasinthe would always find them. As she approached their hiding place she would say, “Fee fie foe fum, I smell the blood of three South Africuns!” And then she would open the door and they would cling, squealing and laughing, to Gloria’s skirt, while their mothers nodded reassuringly at each other.

The game would start with a knock at the door. Ma Vasinthe would look at Gloria who would rush the boys into hiding, while Ma Vasinthe counted slowly and went to answer the door. But the charade soon turned sinister. Once, when they didn’t have enough time to find a good hiding place, they scrambled under Ma Vasinthe’s bed and waited. That was an eerie round and they didn’t enjoy it very much. It frightened them and, even though Ma Vasinthe said that they were imagining things, they knew that from under the bed they had seen the boots of the dreaded Black Jacks come to drag Kagiso and Ma Gloria away. After that, they enjoyed the game less and less.

Purple Rain

SEPTEMBER 2ND 1989 WAS A SATURDAY. When he wakes, still holding their childhood photograph in his hands, that is the day he remembers. Then, as now, his waking thoughts were of Issa, Issa with boyhood lips eternally poised for p. P is for paneer, p is for purple... They hadn’t seen each other for months, not since his birthday in July, in fact, when Sophie, drunk, tripped Issa up and broke his leg. During their years at university, he at the ‘Ivory Tower’ on the slopes of the mountain, Issa at ‘Bush College’ out on the Cape Flats, they had grown apart. But when he opened his eyes on that Saturday morning, he knew Issa well enough to know he would be involved.

The whole country knew about it. He did too. For weeks, the activists in Jan Smuts House had spent their days falling over one another and their nights in long meetings behind closed doors, followed by dinners of hushed whispers, and Tracy Chapman ‘Talkin’ Bout A Revolution’ in the common room, now reserved by unspoken agreement for their exclusive late-night use:

Don’t you know

They’re talkin’ about a revolution

It sounds like a whisper

Don’t you know

They’re talkin’ about a revolution

Their efforts paid off, as thousands took to the streets of Cape Town on that spring day to take part in the biggest demonstration in South African history.

But he wasn’t there, having opted instead for a matinee screening of Dangerous Liaisons in Rosebank with Sophie, Richard and the other bright young things from Upper Campus. Richard Mc Kenna, he thinks. Sophie Scott-Harris. What became of them all?

After the film, they went back to Jan Smuts House; it would be quiet, it wasn’t far and it had started to rain, and town would surely still be a mess.

They had the place and its panoramic vistas to themselves, a welcome change after the weeks of frantic covert planning it had witnessed. They’d stopped for pizza and some wine on the way - Constantia, as Richard rarely drank anything else – and Sophia had brought some hash that they smoked secretly in Kagiso’s room under clouds of incense. The boys agreed that Michelle Pheiffer was gorgeous; the girls did too. Then the girls agreed that John Malkovich was gorgeous, and the boys did too. Everybody agreed that the American accents were distracting. None of them had read the novel and all of them were oblivious to the chaos that had erupted on the other side of the mountain...

The Defence Force, armed with water cannons, had sprayed purple dye on the peaceful protestors as a means of marking participants, and then set about arresting everybody who bore the stains for their involvement in an illegal gathering.

Kagiso and his friends knew nothing of their plight; of the defiant hairdressers who did their bit for the struggle by giving refuge to fleeing demonstrators in their salons, draped them in towels and gave them un-purple rinses; nothing of the desperate crowd who, in vain, sought refuge on holy ground – the police, armed and dressed in full riot gear, raided St George’s Cathedral, in the interest of national security. They knew nothing of the 500 demonstrators who had been rounded up by the end of the day and trucked to police stations around the city.

And then, at around ten thirty, just after they’d heard the punch line to Richard’s joke, the activists – wet, bedraggled and purple – walked under the archway and into a courtyard that was about to explode with gales of drunken laughter. It was not until the tears of hilarity had been wiped away and Kagiso had caught his breath that he recognised Issa, stained purple, staring at him, from among his purple comrades.

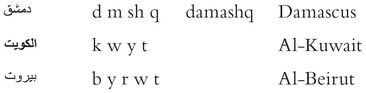

jim, ayn, káf, mim, há,

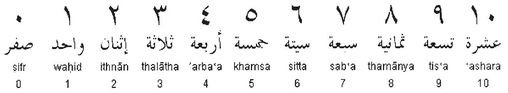

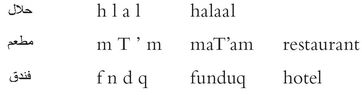

IN HER SUNNY KITCHEN, she closes her reference book and turns away from Karim’s alphabet on the wall. On a clean page, she starts to write down the alphabet from memory – all 29 letters, from alif to hamza, saying each letter out loud as she writes – sound and symbol, sound and symbol. Some letters – bá’  and nún

and nún  , jim

, jim  and kha’

and kha’  – still throw her; like b and d, g andj, they confuse the novice. She has to think carefully whether to place the dot above or below the otherwise identical shapes. Fluency and instant recognition will come with time and practice, she reassures herself.

– still throw her; like b and d, g andj, they confuse the novice. She has to think carefully whether to place the dot above or below the otherwise identical shapes. Fluency and instant recognition will come with time and practice, she reassures herself.

Her favourite letter is m: mini –  – with its loop and tail, a little like a p. She likes the word moemkin – it contains two mims and her other favourite letter, k: kaf –

– with its loop and tail, a little like a p. She likes the word moemkin – it contains two mims and her other favourite letter, k: kaf –  . She likes its look and its sound: m oe m kin. She sometimes talks to herself, making whole sentences with just this word: “Moemkin moemkin moemkin moemkin moemkin!”

. She likes its look and its sound: m oe m kin. She sometimes talks to herself, making whole sentences with just this word: “Moemkin moemkin moemkin moemkin moemkin!”

Now she writes the word moemkin, remembering that the letter  changes its shape to

changes its shape to  when it appears at the beginning or in the middle of a word and the letter

when it appears at the beginning or in the middle of a word and the letter  is written

is written  when it appears in the middle of a word:

when it appears in the middle of a word:  . It means possible.

. It means possible.

Then she writes his name, Karim:  . It means noble.

. It means noble.

She smiles. She can read and write her two favourite words. She touches the tip of her forefinger to her lips and then, gently, to the words she has written on the paper, Karim, possible:  .

.

She opens her eyes, takes a deep breath and moves on to the next phase, memorising the mutations of those letters that change their shape depending on whether they appear at the beginning, middle or end of a word: jim,  ayn, kaf, mim, has’

ayn, kaf, mim, has’  .

.

“I just don’t give a – ”

“THE ANGER,” FRANCES REMEMBERS through narrowed eyes, “came later. First, there was the despair. On that Sunday night, 26 days later, as we watched the bombs start to fall, he fell silent. But I didn’t notice it at first – was too absorbed in what was happening on the screen:

As you all know from the announcement by President Bush, military action against targets inside Afghanistan has begun. I can confirm that UK forces are engaged in this action. I want to pay tribute at the outset to Britain’s armed forces. There is no greater strength for a British prime minister and the British nation at a time like this than to know that the forces we are calling upon are amongst the best in the world.

“The world had lost its moment,” Frances sighs, “and Britain was again at war. Never thought I’d see the day. Of course there was the Falklands, but that was Thatcher’s doing. Wicked woman. This chap on the other hand. I won’t be voting for him again,” she declares, grimacing with distaste and slapping her hand on her armrest with the finality of a judge passing sentence. “And so it wasn’t until I saw his shoulders shake that I realised he had started to cry. I turned -”

Kagiso leans forward. “Frances?”

She shows him her palm. “I’ve just remembered something.”

“that? ”

She starts slowly, like a medium, eyes unmoving, reporting events from another world. “It was a few weeks before he went home for his mother’s inaugural lecture, late August, early September, before the world went mad. He’d started reading a novel earlier in the summer, quite a thick one it was. He read snatches of it to me from time to time.” She shakes her head, annoyed with herself. “What was it called? Never mind,” she says, waving dismissively. “It will come to me later.”

“Anyway,” she continues, “he wanted to finish it before he went home, so he brought it up to the roof the day before he left for Johannesburg. He sat himself down in the driver’s seat while I made some fresh lemonade. When it was ready, I took it out to him and then I let him be.

“Mind you,” she confesses, “I kept peeping out from time to time to see how he was doing. It felt so reassuring to have him out there, his nose in a book. All I could see from here were his big feet stretched out on the crate in front of him.

“When I was sure he’d finished, I peeped out again. This time I saw him hunched over his knees, the book cradled in his lap. I went out to see if he was okay. As I got nearer, I heard sobs.

“‘Issa,’ I whispered. ‘Are you alright?’

“He looked up at me, his eyes red and puffy.”

“Fine thanks”, he said.

“‘What’s the matter?’ I asked.

“The book, he said. It’s the saddest thing I’ve read. And then he started crying all over again.

“We laughed about it afterwards, but even when he left for the airport the next day, I could tell that the story was still with him, there, in his eyes, when he turned around to wave goodbye one last time before going down into the station.

“What was it called?” she asks again, staring hardinto the middle distance, a bent finger tapping at her lips. “I can still see the cover. It had a picture of a little girl balancing on a stick... Never mind.”

She turns to Kagiso with renewed focus. “But the night the bombs started to fall, that night was a different sort of crying. I turned to him but he seemed not to notice me. I strained to hear the words he kept muttering to himself, over and over again.”

There’s nothing there to bomb. There’s nothing left to bomb.

“That was when he started listening almost constantly to the World Service. Its muffled, crackly transmission reminded me of the dark days of the Blitz when we would gather around to listen to the news on a long wave Bakelite wireless that took five minutes to warm up.”

“Welcome to Talking Point on the World Service of the BBC. US forces continue to pound the military installations of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda network and its Taliban protectors inside Afghanistan.

“The US has declared the military operations a great success, but President George W Bush has also warned that the campaign is only the start of a war against terrorism that could last for years.

“Violent protests against the US-led air strikes on Afghanistan have taken place in Pakistan, which threaten to further destabilise the region.

“What is your reaction to the US-led attacks in Afghanistan? Are the strikes justified? What are they likely to achieve? And what could be the repercussions for the people of the region and the rest of the world?

“The lines are now open. Let’s take our first caller, Raymond in Singapore. Hello, Raymond.”

“Yes, I think it unlikely that Osama bin Laden is going to sit and wait for the US forces to capture him in Afghanistan. I assume that if it becomes necessary, he will go underground in some friendly community. Will the US then start bombing other suspects, presumably Islamic countries?”

“And he hardly ever watched the news on TV anymore. He’d still come up here most evenings – more, I think, out of habit and to keep me company – but he always brought a mangled newspaper with him, which he flicked through while I watched the set, or a little transistor radio which he’d take out onto the roof”

“This week in Talking Point: the worst fighting may be over in Afghanistan but aid agencies warn that the refugee crisis will not be solved for years to come.

“There were at least two million refugees in Pakistan alone before the start of the American bombing in October, more than 200 000 are thought to have crossed the border since then.

“Many of these refugees are desperate to return home, but the UNHCR has been urging them not to return immediately, since Afghanistan is not ready to receive them.

“The primary obstacle to large-scale repatriation now is security, as tribal warlords continue to fight over the spoils of war.

“Jobs and food are both in short supply in a country where six to seven million people are reported to remain on the brink of starvation.

“Does the West need to do more to help the Afghan refugees? What should the new government do to help the Afghan people repatriate?

“We’ll go immediately to our first caller, Paul in England.”

“Here we go, another huge flood of welfare claimers and council house takers heading our way. Isn’t it time we told people to go back into their own countries rather than coming in and sucking ours dry – which is the inevitable conclusion if we don’t tell these people to go back to their homes?

“I wouldn’t mind aiding people if they were willing to help themselves – but people are too ready to cry and whinge. When I saw people dancing in the streets and enjoying themselves in their country, it showed me that it can’t all be that bad, and now they’re out from being oppressed they have a golden opportunity to make something great of themselves. They’d have the backing of everyone if they didn’t send their people over here to claim our money from our welfare system and send it home.”

“No. It wasn’t till several months later, not until the summer, following that dreadful incident in Lye, that the anger started to set in.” Frances slips away again, a pensiveness coming over her. “I can still see him sitting in that very armchair you’re in now, circling words in the newspaper article: riot gear, metal battering ram, mosque – children, refuge, deportation. He turned to me, pleading to know...

What sort of society can make sentences out of such disparate words, Frances – casual, matter-of-fact sentences out of such disparate words?

“‘Well,’ I stumbled for an answer, ‘the same sort that only two generations ago displayed signs like: no blacks, no Irish, no dogs. Things have come a long way since then.’”

Yes, Frances, they have – a very long way. Bigoted signs have become battering rams, detention camps and bombs. A very long way, backwards.

“What did happen at Lye?” Kagiso asks.

“Wait a minute,” she says. “I still have the article right here. He dropped it into my lap before he stormed out and disappeared for days. You can read it for yourself.” She retrieves a white envelope filled with prayer cards and parish leaflets from a folder on the smoking table next to her chair. On the envelope, in her careful, old-fashioned hand, is neatly written, Issa’s article, and the date, 25th July 2002. Kagiso opens the envelope:

Mosque raid causes anger

Police yesterday raided the Ghasia Jamia Mosque in Lye in the West Midlands in order to remove an Afghan family that had sought refuge there after the Home Office ruled that they had no right to remain in Britain. The raid caused anger and has been widely condemned by Muslim and human rights organisations.

Police officers dressed in riot gear used a metal battering ram to break down the door of the mosque. The Afghan parents and their two young children have been taken into custody pending their deportation from Britain.

The raid has caused anger and outrage in Britain’s Muslim community. A community spokesperson outside the mosque said that they were angered and disgusted by the way in which the police and the Home Office handled the situation. “Seeing a destitute family hounded and traumatised and our place of worship violated has left us feeling angry and humiliated.”

“That’s when the anger started,” she says resentfully, pointing to the article when he’d finished reading. “After that, there was very little talk of stars or deserts or forgotten histories, no more tears shed over sad books, just an intense, brooding silence. He would come in here, slouch in his chair, and listen with distant glassy eyes as I did all the talking. Not that that was ever a problem, you understand.”

Kagiso laughs. But her smile fades quickly.

“Sometimes I think I may have talked too much. If I’d kept silent more, perhaps that would have made him come out with things, get them off his chest a bit. But I didn’t want to make him feel unwelcome. Didn’t want to shut him out.”

“You shouldn’t blame yourself, Frances. Issa’s always been prone to withdrawal, ever since we were children. He sometimes used to shut himself in his room for days.”

“Well, I still wonder whether if I had – Anyway...”

She removes a cigarette from the box and rolls it in the tips of her fingers for a while. When she has lit it, fearful of the flame, she lays it in the ashtray.

“And I don’t think he was working very much either.”

Kagiso frowns.

“Yes. I came to know when he was writing by a piece of music he used to play. I can hear it now. Oh, it was a beautiful piece. I do miss it. I don’t even know what it was called. Didn’t want to ask. Thought he might think I minded. Didn’t want him to turn the volume down. So I never asked. Suppose I’ll never know now.” She looks up at Kagiso who looks down at his hands.

“Now everything was silent down there, with only the news on the hour, every hour. Beep beep beep, then the announcement of capital cities around the world. If he did play music, it was always that terrible shouting stuff that young people listen to these days. And I’m sure one of the songs – he used to play it often – used to go something like, ‘I just don’t give a – ’, you know?” She raises a palm to her mouth, as if to exclude a child, then mimes an F.

Kagiso nods.

“So if he wasn’t working, then what did he do all day?”

“Well, he washed a lot.”

Kagiso sits up in his chair. “He washed?”

“Yes, his mother reacted to that too. Yes, all the time.”

“And was he... seeing people? Getting visitors?”

“Well, he never used to get any visitors, apart from his friend Katinka, who used to call by from time to time. But even that soon stopped. She buzzed me from outside one night, cold night it was too, when she’d got no reply from downstairs. Thought he might be here with me. I invited her up to wait in case he was running late. But he never came. Furious, she was. And you know Katinka... doesn’t mince her words.”

Kagiso smiles agreement.

“Apparently, he’d stood her up a couple of times before. I tried to ease things over for him a bit – told her I had no idea where he was, that it was unlike him not to be home. Suggested that something must have happened to detain him. But really, he’d taken to going out most nights and often didn’t get back till very late.”

“Did he ever talk about where he’d been?”

“Never. And I didn’t think it my place to ask.”

In the ashtray, the cigarette has transformed itself into a long worm of ash.

‘A road map into our past’

‘The Report that follows tries to provide a window on this incredible resource, offering a road map to those who wish to travel into our past.’

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

October 1998

KAGISO DUSTED ON THE DAY HE ARRIVED. Not that he enjoys housework, only wanted something to do. Decided to start by eliminating the gloomy layer of grime that had settled between him and the flat, as Issa would have known it. The wardrobe was empty, the bathroom and kitchen were left spotless, the small bar fridge was washed, turned off and the door left ajar. Disconsolate relief, everything had been done, nothing to do...

Except pack the bookcase.

It is pleasing to look at, the handsome, commanding proportions of the solid oak, the meticulous alphabetical arrangement of the books on its shelves. Katinka has asked to keep it – she remembers helping Issa collect it from an antique dealer in gentrified Crouch End over the hill. Couldn’t believe what he’d paid for it, couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t make do with something from IKEA. Its contents will be shipped back to Johannesburg. But Kagiso doesn’t want to dismantle it, finds it hard to get started, procrastinates, seeks distractions.

Again he handles the mementos on the shelves; the speedometer from their student banger, Issa had removed it after the car was eventually written off in a head-on collision with a drunken driver – it registers 119 251 km; the jar of sand he’d gathered from the side of the road in the Karoo – Kagiso can still see him crouching – where the car clocked 100 000 km; the poem now posted inside, scribbled on a rolled-up travel card: The story of my life / written in the / sands of time / buried in the / warm dunes / – how many more / caravans will / move on / without noticing / the faint shadow / this ripple creates; the special edition R5 Inauguration Coin, stuck with blue tack to the front edge of the middle shelf.

He wraps the coin in the silver foil from inside his cigarette packet to distinguish it from the other coins in his wallet. Then he raises a reluctant hand to the first shelf but quickly drops it by his side with a sigh, imagining, again, the scenario: What if he comes back? Catches me? What will I say? We thought it best. Had given up on you. Decided to pack up your stuff and take it home, to your room in Ma Vasinthe’s house.

His attention is drawn to a bright yellow note, which sticks out of the top of one book. He opens the book. The note is from Issa to Frances: Found this in a bookshop on Charing Cross Road. Ahead of your trip to Canterbury, I thought you might find it interesting. Kagiso reads the highlighted section:

Part Two:

The Literary Heritage

Chaucer’s Dame Alys, the Wife of Bath, illustrates her expertise in the art of life by quoting two proverbs. They belong to the category of sayings of Arab philosophers which are cited in the Disciplina Clericalis and the Secret of Secrets. But Dame Alys attributes them to the Almagest of Ptolemy:

Whoso that nyl be war by othere men,

By hym shall othere men corrected be.

The same wordes writeth Ptholomee;

Rede in his Almageste, and take it there.

Her opinion of Ptolomy and the Almagest is pronounced with the authority of experience of Ptolemy:

Of alle men yblessed moot he be,

The wise astrologien, Daun Ptholome

That seith this proverbe in his Almageste:

“Of alle men his wisdom is the hyeste

That rekketh nevere who hath the world in honed.”

Chaucer, in composing these passages, was following the example of the Roman de la Rose which gives us an important clue to the exact location of these sayings:

[The tongue would bridled be, as Ptolemy

Early in the Almagest explains

In noble words: “Most wise is he who strives

To hold his tongue save when he speaks to God”]

The source “at the beginning of the Almagest,” from which Chaucer and Jean de Meun drew different proverbs, is of particular importance as it confirms Chaucer’s use of Ptolemy’s Syntaxis in the translation of Cremona from the Arabic. The preface from this version was a biographical note on Ptolemy composed by “Abulguasis.” It contained thirty-three sayings attributed to Ptolemy and was taken from an Arabic work, The Choicest Maxims and Best Sayings, by Abu al-Wafa’ (“Abulguasis”) al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik, a Muslim historian and philosopher who lived in Egypt. al-Mubashshir’s work was composed in 1048-49. It comprises short biographies and descriptions of twenty philosophers, accompanied by a series of sayings under the heading of each, and is related to the widely read compilation of “strange sayings” of Greek philosophers by Hunain ibn Ishaq.

He boxes the book. Rising, he notices again the empty space where the postcard of home used to be. Home, he thinks, was here. And so was –

He positions himself opposite the space. Only the foundations of the towering city now remain. Undiminished, they continue to dominate the bookshelf, like five large cornerstones. His eyes move slowly over the thick black spines, the white lettering that runs down the middle – Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report – the red volume numbers at the base of each – Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5 / Once I caught a fish alive

He sends out a cautious hand to the first volume and dislodges it, slowly. The gentle tug causes the shelf to creak. He hesitates, does not remove the volume entirely from its secure position, only partially, so that it balances, a little precariously, over the edge of the shelf. Cautiously, he examines the protruding cover: a collage of faces, some known (an oath-taking De Klerk, hand raised in the air, Thabo, Zuma, Tutu) others not. He leans forward to read the gravestone pictured in the centre. It is embossed with flags of the ANC and the South African Communist Party:

The Cradock Community and the people of SA salute you in your heroic struggle for freedom, peace, justice and social emancipation. Your blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Long live the fighting spirit of our leaders.

MATTHEW GONIWE

BORN 27 2

2 1947

1947

DIED 28 06

06 1985

1985

REST IN PEACE

NOBLE SON OF AFRICA

He studies the faces of the two anonymous women on the cover, wondering who they are, where they’re from – and about the truth they hope to find, whether they have found it, whether, if they have, they are reconciled to it? Then he notices their eyes, preoccupied, haunted.

He steps back.

“A stage-managed whitewash,” his colleague, Lerato, had spat. “And Tutu wants us ‘to close the chapter on our past,’ with this? When it castrates our leaders and diminishes our suffering. And why? To assuage liberal guilt and pacify fucking bourgeois fears. Don’t think for one moment that we are satisfied.”

He pulls a sleeve across his brow and slides the volume back into its slot.

6, 7, 8, 9, 10 / Then I let it go again.

He studies the contents page in the second volume and flicks ahead to the fifth chapter, ‘The Homelands from 1960 to 1990’. On the title page, a photograph: a young man, able bodied, black; his trousers around his ankles – made, like a boy, to stand in the corner and face the wall. In the foreground is a picture of President PW Botha. Smirking. Kagiso goes no further.

On the cover of Volume Three, a soldier takes aim, a woman is comforted, Mandela embraces Suzman and a headline reads: ‘You left me blind – and I forgive you’.

He removes the volume from the shelf and sits cross-legged on the floor with it cradled in his lap, searching it, like a telephone directory, for names, names he knows – names of the tortured, the missing and the dead:

The case of Steve Biko 18

Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko [CT05004/ ELA] was detained on 18 August 1977 in Port Elizabeth and died in custody on 12 September 1977 in Pretoria.

Security police officers Major Harold Snyman [AM3918/96], Captain Daniel Petrus Siebert [AM3915/96], Warrant Officer Ruben Marx [AM3521/96], Warrant Officer Jacobus Johannes Oosthuizen Beneke [AM6367/96] and Sergeant Gideon Johannes Nieuwoudt [AM3920/96] alleged that Biko died of brain injuries sustained in a ‘scuffle’ with the police at the Sanlam Building, Port Elizabeth.

At the inquest, magistrate Marthinus Prins ruled that Biko’s death was caused by a head injury, probably sustained on 7 September during a scuffle with security police in Port Elizabeth – but that there was no proof that the death was brought about by an act or omission involving an offence by any person.

He follows a footnote to Volume 4, Chapter 5 where he finds Biko’s gravestone being watched over eternally by the prayerful pose of a participant at the proceedings:

BANTU STEPHEN BIKO

HONORARY PRESIDENT

BLACK PEOPLE’S CONVENTION

BORN 18-12-1946

DIED 12-9-1977

ONE AZANIA ONE NATION

The death in detention of Mr Stephen Bantu Biko Stephen Biko was a prominent leader of the Black Consciousness Movement in the mid-1970s. He was detained by Eastern Cape security police in August 1977 and kept at Walmer police cells in Port Elizabeth. From there, he was taken regularly to security police headquarters for interrogation. The two district surgeons responsible for his medical care were Drs Benjamin Tucker and Ivor Lang.

On 7 September 1977, Stephen Biko sustained a head injury during interrogation, afterwhich he acted strangely and was uncooperative. The doctors who examined him (naked, lying on a mat and manacled to a metal grille) initially disregarded overt signs of neurological injury. They also failed to record his external injuries or insist that he be kept in a more humane environment (at least that he be allowed to wear clothes). When a physician was finally consulted, a lumbar puncture revealing blood-stained cerebrospinal fluid (indicating possible brain damage) was reported as being ‘normal’, and Biko was returned to police cells.

Finally, on 11 September 1977, Stephen Biko lapsed into semiconsciousness. Dr Tucker recommended his transfer to a hospital in Port Elizabeth, but the security police refused to allow this. Subsequently, Dr Tucker acquiesced to the police’s wish to transfer Biko to Pretoria Central Prison. Stephen Biko was transported 1 200km to Pretoria on the floor of a landrover. No medical personnel or records accompanied him. A few hours after he arrived in Pretoria, he was seen by district surgeon Dr A van Zyl, who administered a vitamin injection and asked for an intravenous drip to be started.

On 12 September, Stephen Biko died on the floor of a cell in Pretoria Central Prison, naked and alone. The post mortem examination showed brain damage and necrosis, extensive head trauma, disseminated intra-vascular coagulation, renal failure and various external injuries.

Kagiso returns to the Commission’s findings:

THE COMMISSION FINDS THAT THE DEATH IN DETENTION OF MR STEPHEN BANTU BIKO ON 12 SEPTEMBER 1977 WAS A GROSS HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION. [AT THE TIME] MAGISTRATE MARTHINUS PRINS FOUND THAT THE MEMBERS OF THE [SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE] WERE NOT IMPLICATED IN HIS DEATH. THE MAGISTRATE’S FINDING CONTRIBUTED TO THE CREATION OF A CULTURE OF IMPUNITY IN THE SAP.

DESPITE THE INQUEST FINDING WHICH FOUND NO PERSON RESPONSIBLE FOR HIS DEATH, THE COMMISSION FINDS THAT, IN VIEW OF THE FACT THAT BIKO DIED IN THE CUSTODY OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICIALS, THE PROBABILITIES ARE THAT HE DIED AS A RESULT OF INJURIES SUSTAINED DURING HIS DETENTION.

IN VIEW OF OUTSTANDING AMNESTY APPLICATIONS IN RESPECT OF BIKO’S DEATH, THE COMMISSION IS UNABLE TO CONFIRM A PERPETRATOR FINDING AT THIS STAGE.

Kagiso had bought tickets for he and Issa to see Cry Freedom. He’d hoped that seeing the film together would help them put aside their differences, find a way forward – that in it, his love for film and Issa’s commitment to the struggle would find some sort of middle ground. He’d joined the queue early. Tickets were sold out within hours.

Sweet, Issa said when he phoned to confirm their bookings. Very cool. I’ll see you in Rosebank later.

But by the time they got to the cinema, the film had been withdrawn, confiscated by the police at the last minute, even as the first reels had started to run.

Now, sitting cross-legged in front of Issa’s bookcase, it strikes him that, more than a decade later, he has still not managed to fill in all the gaps inflicted upon him by a censorious dictatorial regime. The books not read, music not heard, histories not known, have become, like the holes in the expensive smelly cheese for which he has developed a liking, a part of his truthfully reconciled and liberated life.

He has still not seen the film. To him, it remains a police seizure. That is what lives on, the film itself, a blank space, a smelly hole. He is, he thinks, a little like the front page of a national newspaper stuck in his journal; full of blank spaces:

Our lawyers tell

us we can

say almost

nothing critical

about the

Emergency

But we’ll try:

PIK BOTHA, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, told US television audiences this week that the South African press remained free.

We hope that

was listening.

was listening.

They considered our publication subversive.

If it is subversive to speak out against

, we plead guilty.

, we plead guilty.

If it is subversive to express concern about

we plead guilty.

we plead guilty.

If it is subversive to believe that there are better routes to peace than the  we plead guilty.

we plead guilty.

Below it, he has scribbled: ‘I am a collection of blank spaces, defined more by what I don’t know, than by what I do.’

But the catalogue of crimes in his lap does not record the invisible forgettable survivable blows to the brain by the censor’s axe. He starts to search for his own name: Mayoyo; Kagiso, left stupid after having been lobotomised by the South African Board of Censors in the interest of national security. He releases the pages of the fifth volume from back to front with his thumb. When the headline ‘Finding on former President PW Botha’ flashes past, he catches the page:

102 Mr Botha presided as executive head of the former South African government (the government) from 1978 to 1984 as Prime Minister, and from 1984 to 1989 as Executive State President. Given his centrality in the politics of the 1970s and 1980s, the Commission has made a finding on the role of the former State President:

[...]

BY VIRTUE OF HIS POSITION AS HEAD OF STATE AND CHAIRPERSON OF THE [STATE SECURITY COUNCIL], BOTHA CONTRIBUTED TO AND FACILITATED A CLIMATE IN WHICH THE ABOVE GROSS VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS COULD AND DID OCCUR, AND AS SUCH IS ACCOUNTABLE FOR SUCH VIOLATIONS.

In the front of the volume, Kagiso finds his name:

Mayoyo.

In a list of ‘Victims of Gross Violations of Human Rights’.

He shudders. Seeing his own name in print, there, in black and white, in the directory of national horrors, the feeling rises, like when he saw the new gravestone his grandmother had had erected on his grandfather’s grave, the first time he had associated his name – there, carved in stone – with death, the first indication of his mortality passing through him like a cold wind. The feeling rises, as in DC, when he glimpsed his reflection looking back at him from behind the names of the gratuitously dead in the polished surface of the memorial to the vainglorious Vietnam War. Angered by the audacity, he had turned around and walked away. But now he doesn’t close the volume; rather, he lies down on his back and brings its weight down onto his chest.

When he wakes, his head beside the volumes, his eyes move over the open pages:

It was not a secret march – it was in the newspapers. I remember on the 24th or the 25th Dr Boesak was still negotiating with Mr Le Grange, then Minister of Police. He sent him a telegram to say that this march would be peaceful and, to a large extent, was a symbolic march. There was no idea that we would physically go into Pollsmoor prison and break Mr Mandela out.

A breeze flows through the open window and flips a few pages.

Lionel and Quentin were 13-year-olds and they both died. There were thousands of people, but why did the police shoot the children? Karel sat with Lionel while he was dying – now Karel is suffering because he and his brother where like twins.

Now a strong gust throws open the window. It startles him. He leaps across the small room to secure the banging pane. When he returns to the volume, he finds it open on a book-marked page. His eyes seize the heading “‘Trojan Horse’ killings”. The words stand up like Lazarus in front of him. They don’t resurrect mythological images; those have been usurped. His association, vivid, is from his youth.

Shock waves from the ambush reverberated around the country and beyond. After the attack, Athlone, at the epicentre, dropped its hands from its shell-shocked ears and looked around in dazed confusion. Then, as if in slow motion, it saw three of its boys fall to the ground, dead. The angry, speechless wave that had lapped at hearts for centuries, rose again, each time a little higher than before. In its rising it woke mythology from its age-old slumber, took its language, then sent it back to sleep.

The Trojan Horse and other ambush tactics 168 The Athlone ‘Trojan Horse’ incident that took place in Athlone, Cape Town, on 15 October 1985 is well known: police hiding in large wooden crates on the back of a railway truck fired directly into a crowd of about a hundred people who had gathered around a Thornton Road intersection, killing Michael Cheslyn Miranda (11) [CT00478, CT00472], Shaun Magmoed (16) [CT00472] and Mr Jonathan Claasen (21) [CT00475] and injuring several others.

That night, while Cape Town of the Flats mourned its dead and young, galvanised hearts readied themselves for battle, in Johannesburg Issa lifted a rucksack onto his back and made for the front door, determined to defy Ma Vasinthe if it came to that:

“You can’t go to Cape Town! she asserted, barring the doorway. “What about school?”

School? I’m sorry, Ma, but if you mean that bigoted white liberal bourgeois nest you send us to every day, you can forget it.

Outside a convoy of expensive combis hooted, clenched fists and Palestinian kefiyas and V-fingers raised into the air through narrowly opened tinted windows.

Let me pass, Ma.

“No.” She folded her arms.

Ma. Please. Get out of the way.

“Now you listen to me!” she commanded, waving a stern finger at him. “You’re a child and you will do as I say.”

Yes, Ma. I am a child. And if that makes me a legitimate target in this country then it makes me a legitimate protestor too. Now get out of my way!

“Don’t you shout at me, young man.”

Issa lowered his voice. He glared at his mother from under a furrowed brow. Ma, I’d rather leave the house with your blessing, but if –

Vasinthe dug her heels in. “I’m not negotiating with you.”

Hoot hoot.

Suit yourself. Issa swung around and started running towards the back door.

“Gloria!” Vasinthe yelled. “Lock the back door!”

But Gloria did not obey. When Issa rushed through the kitchen, she looked up from the ironing. Issa paused. They exchanged glances, did not speak. A snatched wordless moment in which they understood each other perfectly.

When Vasinthe entered the room, Gloria said goodbye by glancing at the open door.

Then Kagiso was drafted in. “Go!” Vasinthe shouted, pointing up the driveway. “Stop him!”

Kagiso leapt into action and caught up with Issa at the gate. He grabbed onto the rucksack and started tugging and pulling at it.

Let me go! Issa struggled.

“Hold on to him, Kagiso. I’m coming.”

One of the gleaming combis pulled up to the curve. A door slid open.

“Come, Issa!” a voice called out from the dark, shaded interior. “Drop the bag!”

Issa dumped his restraining baggage and leapt into the combi.

Go! he shouted, when he hit the floor, his legs still dangling through the door.

On the pavement, Ma Vasinthe watched as her son was carried away in an expensive motorcade of defiant resistance. As the convoy picked up speed, she saw V-fingers, kefiyas, Issa’s dangling legs vanish from sight as tinted windows were sealed and solid doors slid shut. When the discreet, blacked-out fleet disappeared around the corner, Kagiso stepped forward to pick up the jettisoned rucksack.

The day after the Trojan Horse shooting, an angry crowd gathered at the St Athans Road Mosque in Athlone. A member of the SAP was shot by the crowd, after which police opened fire, killing Mr Abdul Fridie (29) [CT00607]. On 18th October, a massive security force presence was moved into Athlone.

Armed soldiers and police lined the streets and searched houses while a helicopter hovered above.

When Kagiso replaces the bookmark, he notices a quotation on its reverse side:

And why should ye not

Fight in the cause of God

And of those who, being weak,

Are ill-treated (and oppressed)? –

Men, women, and children,

Whose cry is: “Our Lord!

Rescue us from this town,

Whose people are oppressors;

And raise for us from Thee

One who will protect;

And raise for us from Thee

One who will help!”

Qur’n S.iv.75

The Monster’s Name

WHEN VASINTHE TRAVELLED TO London immediately after Issa’s disappearance, she brought two gifts, one of them a photograph of her and Issa, which now stands on Katinka’s bedside table next to a picture of Karim. Katinka enacts a little ritual here everyday, laying a flower, sometimes just a leaf plucked in passing from a tree, or tilting perfume onto her forefinger then touching it to the frames – her altar to her missing men. At night she always lights the tea light beside it before she goes to bed.

About the picture, she remembers everything – how she had insisted they have it taken, the warmth of the night, the feeling of his strong shoulders under her hand as she pulled him towards her following the hand signals of the obliging stranger to whom she’d given her camera – the date, 11th February 1990. Her words to Issa...

“I want to tell you a story. It doesn’t matter that I hardly know you. I want to tell it to somebody tonight, now, and then never have to talk about it again.”

The previous day, Kagiso had insisted that they give the stranded girl a lift. “Bloody hell, Issa, she could be standing there for hours in this heat.”

Are you mad?

“But that guy’s just dumped her on the side of the road.”

I’m not getting involved in their argument. He’ll turn back for her. He pays the petrol attendant.

“I don’t think so. He looked pretty angry to me.”

Kagiso looks at the abandoned girl. She kicks her rucksack in frustration then, raising a shielding palm to her brow, turns to salute the shimmering horizon. Issa starts the engine and drives slowly out of the forecourt. When they join the main road, he accelerates.

“Issa?”

Forget it!

But Kagiso pulls up the handbrake bringing the car to a screeching stop just beyond where the girl is standing. She runs towards them.

“Cape Town?”

“Yes,” says Kagiso, throwing open the back door. “Jump in.”

“Thank you very much.”

When she has settled down, Kagiso turns around. “What was that all about?”

The girls sighs despondently. “In this country, what else? Fucking racist doos.”

Issa glances at her through the rear view mirror.

“He picked me up outside Bloemfontein. It wasn’t long before I regretted ever getting into his car. But I was glad to have the lift so I just listened. But after two hours of his kak, I just couldn’t keep quiet any more. So I told him why I was going to Cape Town. That’s when he threw me out.”

“Heavy.”

“Ja well, I’ve seen worse. Thanks for stopping. For a moment I thought I might miss it all.”

“That’s all right,” Kagiso says, not looking at Issa.

“You also going down for the occasion?” the girl asks.

“Yeah.”

“I can’t wait.”

“I’m sure he can’t either.”

“I’m sure you’re right.”

She notices a packet of Rizla papers among the paraphernalia on the dashboard. “You guys mind if I smoke?”

“Go ahead,” Kagiso says. “There’s an ashtray in the door.” He leans over the seat to show her.

“Woah!” he exclaims when he sees the fat hand-rolled affair cocked in her fingers. “That thing looks dangerous. Is it what I think it is?”

“Do you mind? We’re in the middle of nowhere.”

“Do I mind? Go ahead, please.” He ignites a lighter. “I smoked my last at a party last night.”

“In that case, you should go first.” She holds out her offering.

“Thanks, man.”

“Transvaal plates,” she comments. “Jo’urg?”

“Yeah. You?”

“Ventersdorp.”

Issa tightens his grip on the wheel.

“Right.” Kagiso says, then holds out the joint.

“Kolskoot!” She exclaims. “That’s exactly it. Ventersdorp in a word.” She takes the joint. “Actually, for an even better summation of my home town, you need to prefix ‘right’ with ‘far’, or better still, ‘ultra’. You get what I’m saying?”

Kagiso nods with wide stretched eyes. “That bad?”

“That bad,” she raises the joint but stops short of her lips. “And my problem with it, to start with, you see,” she says, screwing her eyes to shield them from the smoke, “is that I’m wired differently. As you may have noticed, I’m a left-handed nooi.” She raises the illicit contents of her left hand into the air, “Cheers,” and then brings it to her lips.

“I’m Katinka, by the way,” she says when the music stops.

“And I’m Kagiso. He’s Issa.”

“And does Issa speak?”

“Not very often.”

She nods. “I see.”

“When you guys going back to Jo’urg?”

“Not for a while now. December probably. Maybe June. We study in Cape Town.”

“You’re lucky. I would have loved to study in Cape Town, under the mountains, next to the sea, but,” she sighs, “it wasn’t meant to be.”

“What happened?”

“My father – that’s what happened. He wouldn’t hear about it.”

“Why? ”

“He wouldn’t hear of his daughter going to university in liberal Cape Town. I tried to bargain. ‘Stellenbosch,’ I said, but he had made up his mind and when my father has made up his mind, it’s because his pal, God, has had a say in the decision. So to change it again would be a sin.”

“What did you do?”

“I went to Free State. What else could I do? It was that or stay on the farm. But,” she says with a relieved sigh, as though dropping an unbearable weight, “I’ve finished my course and all that is behind me.” Then she sits forward, squeezing herself between the two front seats to point at the endless open road stretched out in front of them, “and that’s what lies ahead.”

She opens the book on the back seat:

...we had ridden far out over the rolling plains of North Syria to a ruin of the Roman period which the Arabs believed was made by a prince of the border as a desert-palace for his queen. The clay of its building was said to have been kneaded for greater richness, not with water, but with the precious essential oils of flowers. My guides, sniffing the air like dogs, led me from crumbling room to room, saying, ‘This is jessamine, this violet, this rose’.

But at last Dahoun drew me: ‘Come and smell the very sweetest scent of all’, and we went into the main lodging, to the gaping window sockets of its eastern face, and there drank with open mouths of the effortless, empty, eddyless wind of the desert, throbbing past. That slow breath had been born somewhere beyond the distant Euphrates and had dragged its way across many days and nights of dead grass, to its first obstacle, the man-made walls of our broken palace. About them it seemed to fret and linger, murmuring in baby-speech. “This,” they told me, “is the best: it has no taste.” My Arabs were turning their backs on perfumes and luxuries to choose the things in which mankind had had no share or part.

She glances at their silent driver and lays down the book, her fingers brushing the tattered flag pictured on the cover. “What is this music?” she asks of the lilting, sorrowful tune.

“It’s his.”

“What is this music?” she repeats. “I’ve never heard such music. Where’s it from?”

He says his first words to her. It’s –

She is surprised. “But that’s banned.”

Issa doesn’t respond.

“Well, it is beautiful music. Like the desert. Like here.”

It is night by the time they approach the mountains that encircle Cape Town. Scatterings of light betray the sleepy villages in the dark valleys below them, while the golden glow of the city beyond hangs over the peaks above, like a halo.

“I’ve not yet seen the new tunnel. I’m told it’s quite impressive.”

Kagiso looks at Issa.

“I believe they built it from both sides of the mountain. Apparently, when the two tunnels met, they were only millimetres off.”

It’s getting late and he has been driving for sixteen hours. Tomorrow will be another long day. At the fork in the motorway, the moment of choice between the tunnel and the pass, Issa makes for the tunnel.

Minutes later, they are racing down the N1 on the home run to its southernmost destination. To their left, the Cape Flats – a carpet of light stretching all the way to False Bay, glides by. Ahead, a sweeping bend brings Table Mountain slowly into the view, lit up against the night sky. There is an air of anticipation in the city.

At last the sun has set.

Dawn will usher in a long-awaited new era.

And steering the car between the flashing white lines on the freeway, a quote comes to hover in front of Issa’s tired, driving eyes: “The morning freshness of the world to be intoxicated us.” That is all he wishes to remember of it and tries hard to ignore the rest of it. But the passage lingers, demanding to be recalled in its entirety: “yet, when we achieved and a new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew.”

“I wonder what he must be feeling now,” she says, almost to herself.

The next night, when the crowd on the Grand Parade starts to disperse, they walk across town to the Underground. Inside, the atmosphere is euphoric. Issa’s entrance is greeted with hoots and cheers.

“Amandla!”

“Awethu!”

“It is true, isn’t it?”

“It’s true.”

Katinka is greeted with cautious reserve.

“Ek sê my bra,” Issa’s friend starts up when they are alone, “leading the way to reconciliation by example, or what? Who’s the lanie nooi?”

Issa looks across the room to where Katinka has blended effortlessly into the celebrations. He felt called upon to deliver his verdict, his final interpretation of the bits of evidence she had laid before him during the course of the day. As he watched her dance, rejoice, hands high in the air, it came to him: The system imprisoned all of us.

He turned to his friend: She’s a comrade from the Free State. So don’t you give her grief.

“Nooit, my bra. If she’s with you, I knew she had to be cool.”

Coolest you’ll meet.

“Vir seker!” his friend nods with envious admiration.

From the crowded dance floor, Katinka catches Issa’s outline, crouching in a dark corner, his neck crooked as he stares into the space above her head. She follows his gaze to the ceiling above the dance floor. Being projected there, are images of the day’s unimaginable events: the huge crowd that gathered outside the prison to greet him, waiting, for hours; the moment when he appeared, actually appeared, there, in front of them, walking into their midst, like the Messiah; the hush that fell, then the rising murmurs, the grappling with the most indescribable complexity of emotion, all of it, pent up, with him, for 27 years; then, the release, the catharsis, the ecstatic jubilation, here, in the city, across the country and around the world.

“Amandla!” someone shouts from the dance floor.

The whole Underground responds with a deafening chorus, which overpowers the thumping sound system: “Awethu!”

The sequence ends with the face of the man as he now is, emerging, slowly, from behind the blacked-out profile of his banned image – till today, apart from a few black and white images that predated his censure, the only image their generation had of him.

Gerry Adams at least had a face.

When she looks down from the ceiling, she finds him looking at her. He does not look away. She walks over to him.

“Wat dink jy?” she asks, crouching on the floor next to him.

Not much.

“Good.”

The response surprises him. Why good?

“Well, if you’re not thinking much,” she explains “then you won’t need to use too much of your daily fifty-word ration to share your thoughts.”

He tries to stifle a shy smile.

She raises her head encouragingly.

I’m thinking of those who can’t be here. My friends. Coline. Robert.

“Ag, forget about them,” she says with a dismissive wave. “If they can’t be bothered to be here, today of all days, they don’t deserve your thoughts. Absconders. Forget about them.” She grabs him by the hand and stands up. “Come. Dance.”

But he breaks free. And if they’re dead?

Her face falls. “Oh my God!” She slides down the wall, back into her crouching position on the floor. She buries her face in her hands. “I’m so sorry.”

Katinka?

Comrade?

Hey! He takes her gently by the hand. Don’t worry about it. It’s okay. Come on.

She crawls out cautiously from behind her hands, wiping tears from her cheeks.

Hey!

“I thought – I thought you were talking about... People like...”

Like?

She sits up with a sniff. “I want to tell you a story,” she says, resolutely wiping away the tears. “It doesn’t matter that I hardly know you. I want to tell it to somebody tonight, now, and then never have to talk about it again. It must die with the old. It’s only a short story. Will you listen?”

Yes.

“One day, there was a brother and a sister who grew up on a farm outside Ventersdorp. When they were naughty or when their parents wanted to force them into things like homework or going to church, which the little girl hated, they would threaten them with a monster, saying that, unless they did as they were told, the monster would come for them in the night, drag them from their beds and devour them.

It was a horrible monster, ugly and cruel, and even after years had passed and the brother and sister had grown up, the mention of the monster’s name still struck fear in some part of them.” She looks at him nervously. “Can you guess the monster’s name?”

He thinks.

What? Not – ? He gestures to the images on the ceiling.

She nods.

Nooit!

Then looks away. “When I told my father I was coming here today, he said, ‘Kies! If you go, you are not welcome in my house any more. You are not my daughter any more. What do you think the people will say? How do you expect me to face them with a daughter who runs after a communist terrorist kaffir?’ And my brother, he said he’d shoot me himself if he ever saw me again.”

She looks up at him with overcast eyes. “Fluit, fluit,” she says with a sad smile. “My storie is uit.”

The Sanctuary

KAGISO HAS FORGOTTEN HIS JOURNAL, so he unlocks the door again to fetch it from the desk. It is open at an insert, an extract he was once asked to read in an undergraduate tutorial. It seems almost innocuous now so that he snatches the journal without fully noticing the open page, but at the time the extract brought his world crashing down around him. It was what first prompted a revision of his black and white mind film:

... Fifteen years later, in Cape Town, comes this brief glimpse of young mother, Lydia. Divorced with one child, she went back to look after her 86-year-old mother who lived with her husband in a house tied to a lime-stone processing plant whose owner forbade anyone else to stay with them. Thus, since Lydia was not allowed to stay there she has been running from the police. She and her one-year-old baby were amongst those arrested in a police raid. They spent the weekend in jail and were only allowed out because of the baby. She had to reappear in court and, at the time of the interview, did not know what the outcome would be because she did not have money to pay the R20 fine. She did not have anyone to support her. She had divorced her husband about six years previously, but although he was required to support her and the child financially she had not received a cent. “She has been in court many times for a maintenance grant but is tired of this because nothing ever materialises” (15:4). Lydia, writes MM Gonsalves, is tired of trying to make ends meet as well as running from the police. She states that no matter where one goes, if one does not work and ‘live-in’, and does not have a pass, one has to run, because of the danger of trespassing. She begs for a live-in job as she cannot stand the thought of being caught again and of being constantly on the look-out for the police (15:5).

When the tutorial was over, he returned to his room at Jan Smuts House and locked the door. He skipped classes for the rest of the day and in the evening, went to see Issa at UWC.

Kagiso roams the city – sometimes with Katinka, mostly by himself. No matter how late he goes to bed, he always wanders through the early morning streets, when security shutters on shop fronts in the neighbourhood are being lifted slowly, like sleepy lids, before the streets become crowded. While the destitute are still visible – bundles huddled in doorways, before being swept away into obscurity. Where faces are obscured, he looks to other features: ears, hands, fingernails especially – large, even and with unusually prominent half-moons – shoulders, hair, scrutinising them, not in order to classify and exclude, but to identify and embrace.

One morning, he plucks up the courage to talk to the fruit vendor, still setting up his stall. “Good morning,” he says, nervously.

“Alrigh’ mate? No’ quite ready yet.”

“That’s okay. I was only wondering if...”

The vendor straightens himself.

“If...” Kagiso starts from scratch. “I believe you know my brother.”

The vendor looks at him, confused. “Bruva?”

“Yes. He used to barter with you, fruit in exchange for the sports section of the paper.”

The vendor throws his head back in recognition. “Oh, yes, sure I do. Yeah, ‘e used to come by ’ere regular. I was only wondering abou’ ‘im the other day, like. ‘aven’t seen him for a while. He alrigh’? ”

“Actually...”

The vendor leans forward.

“Actually, he’s disappeared.”

“Your ’aving me on! Disappeared?”

Kagiso nods.

“When? How?”

“Four months ago. In April. That’s all we know.”

“And you’ve ’eard nuffing since?”

Kagiso shakes his head. “Nothing.”

“You mean to say somebody can disappear,” he snaps fingers, “just like that?”

“Seems so.”

“Well, I am sorry to ‘ear that, mate. I really am. Nice bloke ’e was, too. Mind you, he never said very much. Came ‘ere one morning, bough’ a banana and gave me the sports paper. Always a banana. Same thing ‘appened again the next morning, and the next, till I wouldn’ take ‘is money no more. ’ad to be fair, like, you know what I’m saying?”

“So he didn’t say anything to you before he left?”

“Nah, he didn’t say nuffing, mate. As I say, he never said much anyway.” The vendor scrutinises Kagiso a little more closely. “You say you two was bruvas?”

“Yes.”

“Thought so. But he was more kinda Arab looking, weren’t he? ”

Kagiso nods.

“Don’t mean to pry, like, it’s jus’ that, for a moment I weren’t sure, you know, if, we was talking abou’ the same person, you know wha’ I mean? ”

“That’s okay. Don’t worry about it. Listen, if you hear or see anything,” he hands the vendor his card, “would you get in touch?”

The vendor studies the card. “Johannesburg, ’ay?”

“Yeah.”

“That where ’e was from, too?”

“Yes.”

“See, I didn’t even know tha’ much. Aint life funny sometimes?” he asks, searching the sky. “You can see somebone every day of yer life and know nuffing abou’ them, until they disappear. Tha’s London for yer, mate.”

Kagiso rocks back on his feet awkwardly.

“Sorry, mate, I didn’t mean to upse’ you, like.”

“You didn’t.”

The vendor is not convinced. He places Kagiso’s card down on a box and opens another. “‘ere, take a banana.”

“No, that’s not -”

“Go on,” the vendor insists, stuffing the banana into his pocket. “‘av it.”

Kagiso relents. “Thank you.” He looks at the card. “You won’t forget, will you?”

“Forge’?” the vendor asks.

Kagiso points at the card. “To be in touch. If you hear anything?”

“Sure, mate,” the vendor assures. He slips the card into his back pocket. “Anyfing I can do, mate. Anyfing I can do.”

Later in the day, the heat, inescapable, follows him like a stalker, from Issa’s tiny flat, onto the tube, through the busy streets.

“I’d have thought you’d be used to it,” Frances commented when he complained.

Kagiso muttered a vague, concealing response; at home he rarely has to confront the weather, his contact with it always mediated by his air-conditioned car, his modern office in a shady northern enclave of the city, his spacious, well-ventilated flat with its balcony overlooking the pool. London is a different world; he has twice had to rush off a baking stopping starting swerving turning sitting bus for fear of retching. On the tube, he tries, whenever possible, to stand by the door at the front of the carriage where he can let the window down as he has seen experienced commuters do.

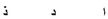

With him, he carries his journal, a water bottle, a camcorder and Issa’s A-Z and notebook, which he found at the bottom of the bookcase and some of the ‘Missing’ leaflets of Issa to distribute when the desperate compulsion to do something takes hold. He visits the places Issa mentions in the notebook, to see for himself the new British Library, impressive inside but which from the street looked to him like a prison (he much preferred the building next door, was amazed to discover that it is, in fact, a station); Trafalgar Square, destination of protest, prestigious location of South Africa House and, to his surprise, just there, in the middle of the city, the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, not at all the setting he’d imagined when their evocative soundtracks carried him on sentimental cinematic journeys to magical places, now, he doesn’t even step inside; the parking lot in front of Westminster Abbey, called ‘The Sanctuary’, the location of a black and white photograph in Issa’s notebook: a young Mandela before his eventual imprisonment and total censure.

From here, Kagiso winds his way through the narrow sunless back streets behind the abbey, past the offices of the Liberal Democrats on Cowley Street, then pausing further along to read a sign outside a house, the home of Lord Reith, first director of the BBC, before finally turning the corner into Barton Street. He is looking for number 14, so he starts to count the numbers on the front doors of the neat deserted terraced row – 10, 11, 12, 13 – odd and even next to each other on the same side of the road. Even though he knows it is next, still, in the end, after all the years, number 14 comes upon him rather suddenly, so that he has to step back a pace to study it.

Little distinguishes the house from the other near-identical houses on the quiet street, only a round blue plaque, like the one outside Lord Reith’s, from the Greater London Council, reveals why Kagiso felt compelled to investigate Issa’s mention of this address, also referenced in the brooding quotation above his desk, in his notebook:

TE Lawrence

“Lawrence of Arabia”

1888-1935 lived here

He finds a slight recess across the road and slips into it, looking up at the attic, willing the curtain there to twitch, expectant, remembering the soldier in blind Alfredo’s story who waits 100 nights in the street beneath his true love’s window. Kagiso looks left then right, up then down the quiet little street, barely registering the ding-dong ding-dong that comes rolling over the rooftops. When he moves away from the little house, he looks, one last time, over his shoulder at the attic before turning the corner. He glances at his watch just as, having struck its final stroke at four, Big Ben falls into silence.

Kagiso spends a lot of time at his destinations around the city. He is attentive to them, watches them, their other visitors, finds a good vantage point from which to sketch them, photograph them. Where possible, he always visits the restrooms before leaving, never fully aware that he is searching, always waits for the occupants of locked cubicles to emerge, before leaving.

On Grosvenor Square, he stops to film the sealed-off building on the west side of the square – the barricades, the closed road, the enormous spread-winged eagle that adorns the top of the otherwise unremarkable building. He has been recording the country’s embassies whenever he visits a capital city, storing the images in a folder entitled: ‘The fortressed look of freedom and democracy.’ He does not linger here but retrieves Issa’s notebook from his backpack before continuing down South Audley Street in search of the secluded garden with a secluded bench on which is inscribed the following dedication:

In Memory of Derek Lane

From a select number of friends who spent many hours in his company and together enjoyed the splendour of this city and the tranquillity of these gardens.

Issa had copied the dedication into his notebook alongside a little map of the area showing the location of the park and the bench where he wrote:

Mayfair

24th December 2000

I am sitting on Derek Lane’s bench tucked away in the affluent heart of this splendid city, but, with my own accursed ‘Sixth Sense’, I only see the ogres – the hideous ones, the invisible ones. They roam the city, the unwanted ones, with vacant, distant stares. Absent and preoccupied, here only in unwanted, despised, brutalised, foreign body; Europe’s untouchables.

From the top decks of busses, they scan the bustling pavements of the begrudging sanctuary, searching, desperately, for familiar scenes from home – the smiling face of an old school friend waving enthusiastically from the crowd; the old men at the café on the square, drinking coffee in threadbare jackets, sporting medals from wars only they can recall; the hands of the orthodox priest being kissed fervently by suppliant devotees in the market place; the teenagers with lean, healthy bodies, diving from the old pedestrian bridge – no longer there – into the warm glow of the setting sun.

Sometimes they stare at memories of torture chambers, at missing relatives, at dead friends, right there in the piece of floor between their feet on packed underground carriages, or in the unbelievably pretty shop windows at Christmas time, filled with price tags that could bring whole families to the sanctuary.

At the carwash on the corner, they catch sight of what they fear most in the polished chrome of shiny cars and buckets of dirty water; others see it in mirrors in hotel bathrooms or in the shiny cutlery they lay out before breakfast – reflections of self. Embarrassed, they look away. How could I have imagined that here, this, would be better? When they are still there? Did I leave to live with mocking reflections? Waiting on tables with an apron cut from a graduate’s hood; mending shoes – my grandfather’s trade – with the skilful hands of a surgeon.

Those who believed

And those who suffered exile

And fought (and strove and Struggled)

In the path of God, –

They have the hope

Of the Mercy of God:

And God is Oft-forgiving, Most Merciful

(Qur’an S ii, 218)

For work, they do the jobs these people no longer want to do for themselves. They washed the limousines for Saturday’s wedding in the big church on the hill, tended the garden in the hotel ahead of the lavish reception, which was celebrated into the night. In the morning, they served them breakfast, and then, after everybody had set off on the journey back home, bleary-eyed and hung-over, they stripped their beds and washed their sheets stained with vomit and cum. And at the airport, they cleaned the toilets on the very plane that months earlier had brought them to the sanctuary and which would that night whisk the newly-weds off to their sun-drenched honeymoon, there.

At night they return to their lairs, where the corridors echo with anguished sobs and moans; where memories – of a carefree childhood with siblings, now dead; of frail grandparents, shell-shocked that their many years of toil and sacrifice had not made it all better; of lonely, fretful, wives, unable to escape from under the captive gaze of vigilant government gangs; of anxious parents filled with self-loathing and reproach for not having done more to prevent it all from going so horribly, horribly wrong – all come alive in vivid multicolour home cinema with surround sound on grubby walls and ceilings in the middle of the night, making sleep impossible.