III

The Café

‘when the Reagan Administration began its war with Nicarargua, I recognised a deeper affinity with that small country in a continent upon which I had never set foot. I grew daily more interested in its affairs, because, after all, I was myself the child of a successful revolt against a great power, my consciousness the product of the triumph of the Indian Revolution. It was perhaps also true that those of us who did not have our origins in the countries of the mighty West, or North, have some things in common – not, certainly, anything simplistic as a unified “Third World” outlook – but at least some knowledge of what weakness was like, some awareness of the view from underneath, and of how it felt to be there, at the bottom, looking up at the descending heel.’

Salman Rushdie

Jaguar Smile

1987

Vasinthe’s Letter

IN JOHANNESBURG, VASINTHE HAS BEEN agonising over it for days. Not about whether to write it – she does not dispute his right to know, or, for that matter, hers to tell him – but about how and what to write. That was what bothered her. She hasn’t heard from him since that near-fatal morning when he stormed out of the house, leaving her –

She shuts out the memory.

He must know of the son that was born minutes later. She’d given him the name they’d agreed upon, the name he had wanted. She had written to him at his parents’ to tell him.

Faced with a silence of more than 30 years, she could not decide on what to say, what to leave unsaid.

Not even on how to begin.

But now it is written. Short, she decided, was best. She reads the letter one last time:

Johannesburg

30th August 2003

Muhsin

I regret that I have been unable to make direct contact with you at this time. I would have preferred to speak with you in person. I wasn’t aware that you no longer live in South Africa – though where, your sister would not say. But she assured me that, if I wrote, she would see to it that my letter reached you. She may in fact already have told you my news; I am pleased that they seem to have reconciled with you.

I feel it incumbent on me to let you know that Issa has disappeared from London where he was studying. I have always been certain that, whatever our past, yours and mine, I would inform you if anything happened to your son. And now it has.

My first instinct was that he might have gone in search of you. I cling to the possibility that this is the case – although, as the weeks and months pass, it seems less likely. It has been four months now. But I trust that you will let me know if he does turn up on your doorstep. I assume he is not already with you; whatever has happened between us, I think you would at least have let me know?

You’ve never seen Issa, so I am enclosing the most recent photograph we have of him, taken by a friend of his in London a few months before he went missing. I think you’ll agree that I may as well have sent you a picture of yourself at that age.

Vasinthe

She joins the queue at the small campus post office. While she waits, she retrieves the photograph discreetly from the unsealed envelope. It is a bright picture, taken in Katinka’s sunny flat; one of the pictures they left with Margaret. Issa is leaning against a doorframe, smiling, as he does, has always done, only slightly, head at an angle, arms folded casually across his chest. His thick black hair is swept back from the high forehead and falls in sleek waves on his shoulders. Muhsin, she thinks again: running a trembling finger down the strong nose and along the jaw, wiping the deep eyes gently with a tender thumb. The resemblance only struck her recently.

She has been unable to recall her son’s face; is kept awake at night by faceless memories of him. She can conjure countless images of him as a child: following the trauma of his birth, the relief, when Gloria handed him to her, of holding him, bloody and blue, in her arms for the first time; the way he’d sit, legs crossed on the floor in front of the television, engrossed by the adventures of Lawrence, crossing the Empty Quarter with him, tensing himself, rocking anxiously backwards and forwards, when Daud falls into the quicksand, sitting up on his knees as the struggle to save him grows more and more desperate, rewinding his favourite scenes over and over again until he could recite whole stretches of dialogue.

She can still hear him now: “What is it, Major Lawrence, that attracts you to the desert?” / “It’s clean.” The confused expression on his face when, chasing Kagiso at a picnic, he stepped onto something concealed in the long grass. The terror when he sat down, lifted his bare foot and saw a broken bottle neck stabbed into his sole. Kagiso’s question, asked sheepishly on the backseat during the rush to hospital: “Does it hurt?” Issa’s response, recited in a swoon: The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts. The giant teardrop that welled up in his right eye, like Pharaoh in Tadema’s ‘Death of the first born’ she always thought – suspended in that throat-clenching moment of utter devastation, the teardrop welling up slowly, first in one eye, later in the other, before breaking free of the lid, then rolling down to where it dangled, for just a moment, from the tip of one of the long lashes before its gathering pear-shaped weight sent it falling, down and down till it landed, plop, on the official advice of his Matric results.

Vasinthe can recall all this detail over and over again, but she has almost no recollection of the young man he’d turned into in Cape Town, the man in London. She now keeps a copy of this photograph in a silver frame – a gift from Katinka – by her bedside and one on her desk, the first personal memento to encroach on her professional domain. The queue inches forward. She becomes aware of the cold. She has come out without her jacket.

She recalls an incident some years earlier when a colleague lost his son in a motorcar accident. A few weeks after the funeral, he came into her office:

“They’ve found a cornea for Mrs – ”

“At last!”

“But can you do it?”

“What do you mean? We’ve been preparing this one for months. And you’re the ophthalmologist. This is your case. I don’t understand?”

He stepped forward, “Please?” She could smell that he’d been drinking.

“Bloody hell, Peter! How much have you had? We can’t postpone. How long will it take to – ”

“Too much. Too long. Look, we’ve worked on this one together. This was your referral.”

“I know I can, but that’s not the point, Peter,” Vasinthe shouted. “I haven’t had time to -”

Peter interrupted her. “I’ve got the file here. We have time. Let’s sit down with it. And then we can go to inform her.”

“Of what? That her surgeon can’t operate because he’s bloody drunk.”

“Vasinthe, she knows you. She was your patient too.”

“You sneaky shit! You knew that all along, didn’t you? That the team would cover for you. That’s why you went and got yourself bladdered.”

“Look! I know I’m out of order – ”

“But remember that old adage, Peter, the one about strong chains and weak links.”

He looked pleadingly at her. “Vasinthe, this isn’t helping.”

She exhaled deeply.

He watched her for a response.

“Okay,” she sighed. “I don’t have much of a choice, do I? But we’ll have to inform the super. It’s very late to be swapping the lead surgeons.”

“But you’re the Head of – ”

“Yes, and I’ll deal with you in that capacity on Monday. For the moment, talk me through the latest progress. Where’s that file? Who’s assisting?”

He flopped into her armchair, despondent relief hanging over him.

“I’m sorry Peter, I don’t mean to be harsh, but we’ll have to play this one by the book. You know what’s at stake here.”

He dropped his head.

“Look, is there anything I can do?”

He looked up at her, his red eyes welling with tears. “It was only when I went to identify his body, when I saw him lying there, lifeless on a tray in front of me, that I realised...”

Her expression softened.

“That I realised what a beautiful son I had. Even with all those fatal injuries. He looked like a god, fallen in battle.” He swivelled the chair round to face the window. “Too busy making medical history here to even have noticed.”

In the queue, Vasinthe shudders. She’d registered the words as he spoke them and made private little pledges to herself, but her progression to a JME appointment, the celebrated success of the difficult transplant, the flurry of invitations to overseas lecture-tours, Peter’s disappearance into an obscure early retirement on his remote ancestral farm somewhere in the Eastern Cape – it was easy to forget about his regrets when work was so rewarding. She’d forgotten about the pledge until asked by Margaret in London during their preliminary telephone conversation for a description of Issa. She fumbled. Margaret suggested they finalise the description when she came to the office the following day.

“Can I – ” She started hesitantly. “Can I bring along his friend? She knew him very well.”

“Of course you can,” Margaret said, reassuringly. “Our role is to support family and friends alike.”

“After you, Professor.”

Vasinthe looks up, startled by the familiar voice. She hadn’t noticed her student ahead of her in the queue. She quickly slips the picture back into the envelope.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, please. You go first.”

Vasinthe smiles thanks. She steps forward and places the sealed envelope on the scales. “Special delivery, please.”

“Where to?” the cashier asked.

“Durban, please.”

Walking back to her office, she tries to recall the picture. She remembers that it is bright. She can recall folded arms, a leaning posture, a slight smile – but that is all. She becomes agitated. Muhsin, she thinks, as she tries to reconstruct the son through memories of the father. But all she gets are crazed blood-shot eyes, flaring nostrils, clenched fists, a kick in –

When she reaches the department, she increases her pace into a doctor’s determined stride: “See their white coats flapping, Sinth. See their stethoscopes.” If you stop me now, someone will die. She can’t remember where she’d heard the comment, but she cringed in recognition.

Normally she makes a conscious effort to be less hurried around the office. This is a different space, and though busy, it doesn’t demand the urgency that accompanies her life-or-death role in the hospital up the road. Here, she is Professor Kumar, the teacher, the researcher, the scholar. She makes herself amenable, approachable. She smiles and, from time to time, stops in the corridors to exchange pleasantries with colleagues and students.

But not now.

She does not enter her office as she usually does, via that of her assistant, but slips in through the private, back entrance. At her desk, she reaches for the framed photograph of Issa hidden beside her monitor and slides it into the centre of the desk in front of her. She doesn’t hear the students streaming out of the adjoining lecture theatre and into the sunny quad behind her. She runs her forefinger slowly around the edges of the frame, then rocks it gently from corner to corner.

Like a cradle.

She picks up the receiver:

“Yes, Professor?”

“Susan, can you get Professor Godfrey on the line for me.”

Susan hesitates. “Professor Peter Godfrey, Professor?”

“That’s right.”

“Certainly, Professor.”

“And Susan – ”

“Yes, Professor?”

“Hold my calls.”

“Yes, Professor.”

Another Brick in Another Wall

KATINKA AND KARIM WOULD LIE in a knot and talk through the night, of London and of home. Not sleeping, sinking into each other’s stories like water into sun-cracked earth, like salve into raw wounds.

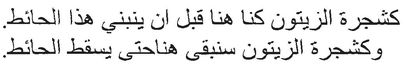

One night, he tells her about the wall that is being built across his family’s property. It will separate their house from their decimated olive-grove, their last remaining trickle of income. The wall surrounds their town on three sides. Most of the businesses in the town have shut down. “It is eight metres high. We never see the sun. Our house is always in its shadow. When I look through my bedroom window that is all I can see. The Wall. It does what it was designed to do; make us feel small.”

Another night, he tells her about Wafa Idris. “It’s not what I would do, but I understand why she did it. Here, in the free world, even the prime minister’s wife was not free enough to say that, but I can. You know: ‘When this life makes you mad enough to kill / When you want something bad enough to steal.”’ They laugh at his imitation of the rap.

“I understand why she did what she did. And those who tell you otherwise, let them spend one day in the life of Wafa and others like her – my father.” He raises a solitary finger into the night, then lets it rise and fall three times, once for each word: “Just one day.”

One night, she comes to hear of her mother’s death. Despite all the years, the news, the indirect route by which it reached her, months later, leaves her devastated. She goes to find him but he isn’t there. She can’t think of what to do. She doesn’t want to go back to her empty flat. She doesn’t want to see Issa. She only wants him. So she sits down on the pavement outside his building because it’s his pavement, it’s the pavement outside his building. She barely notices the cold, barely notices the two hours before he returns.

When he gets home, he sees her huddled in the shelter between two cars. “My God,” he exclaims and scoops her up in his arms. “Why didn’t you come to the café?”

But she is unable to speak. She just lies face down on the bed, crying – not the inhibited sobs of earlier, but a terrifying, howling lament that she is only brave enough to release because he is now with her.

When she wakes in the middle of the night, thick-eyed and dry-throated, she finds him watching over her:

“What’s the matter, habibti?” he asks, tilting his head pleadingly to one side, running his fingers through her hair.

She tells him.

“So you will be going home soon?”

“No.”

He doesn’t understand. He offers to lend her money – money he himself will borrow, if money is the problem.

“It’s not money,” she says. “It’s history.” He is the only person to whom she repeats the story about the monster’s name.

On their last night together before he returned home – “Hell on Earth, but hey, apart from you, this is not that great either. I don’t know what I’ll do. Home is like a ghost town now, I’m told. But I’ll have my family and my friends, and they’ll have me. They need me” – he gave her an inexpensive watch with Arabic numerals. She put it on immediately.

“Now you’ll never confuse seven and eight... And, insha’allah, you won’t forget me.”

“I won’t forget you.”

He sniffed. “That’s what they all say.”

“I’m not like that.”

“Then maybe you’ll visit, one day?”

She lifts herself onto her elbow and lays her hand on his shoulder: “‘Except for thy haven, there is no refuge for me in this world other than here / There is no place for my head.’ I’ll come visit, I promise.” Then she snuggles back into him.

He smiles a fading smile. “Come soon,” he says. “Before we’re completely walled in. While we’re still there.”

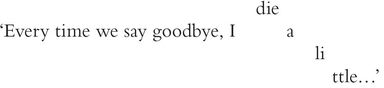

On her first night without him, she compiles an indulgent playlist, which she names ‘Melancholy’. Some of the songs on the list, she hasn’t heard for years. When the selection is complete, she puts it on continuous play and goes to bed:

In the middle of the night, ‘They’re dancing with the missing’ - a tune she once used in a teaching practice lesson when she was a student in the Free State – ‘They’re dancing with the dead’ – a way, she thought, of alluding tangentially to the horrors of apartheid. ‘They dance with the invisible ones’. She failed the lesson. ‘Their anguish is unsaid’. Her subject was South African history. ‘They’re dancing with their fathers’. Not Chilean. ‘They’re dancing with their sons’. She sees herself in a vigil of veiled women. ‘They’re dancing with their husbands’. Around their necks are draped photographs, pictures of the dead. Some women have so many photographs around their necks that other women have to help them, like bridesmaids attending to a bride. ‘They dance alone’.

One of the women steps forward and walks towards the police barrier. ‘It’s the only form of protest they’re allowed.’ When the woman reaches the barrier, the police step forward to block her way. She removes the veil from her face. Decades of sadness bursts from under her veil, causing the police to shield their eyes and step aside. ‘I’ve seen their silent faces scream so loud’. When the unveiled woman reaches the main gates, she turns around to signal to the other women. They follow her up the short street and through the already-open shiny black door. ‘If they were to speak these words they’d go missing too’. One by one, the women enter the house. ‘Another woman on a torture table what else can they do’. One by one, they place their photographs next to those of the happy family on the mantle piece. ‘They’re dancing with the missing.’ One by one, they lay down the pictures of their missing and their dead. ‘They’re dancing with the dead...’

When she enters the house, she realises that she too has a picture draped around her neck. She enters the room and moves to the photograph of the woman on the mantelpiece. ‘Can you think of your own mother / Dancin’ with her invisible son’. She lifts her photograph from her neck and places it on the mantelpiece next to the smiling woman.

‘They’re dancing with the missing

They’re dancing with the dead

They dance with the invisible ones

Their anguish is unsaid

They’re dancing with their fathers

They’re dancing with their sons’

When she sees the photograph she has placed, she wakes and shouts his name into the night.

‘They’re dancing with their husbands’

It is a picture of...

‘They dance alone’.

“Karim!”

One day, she will be on a train, looking out through the window, only half-conscious of the story a mother next to her is reading to her daughter. When the train enters a tunnel, her ears will take over from her eyes: “...but Salim had fallen in love with the court dancer. When Akbar heard of this, he warned his son to give her up, but the prince refused. And so the Emperor ordered his masons to bind the girl and then build her into a wall while she was still alive.”

When she gets to school, she will resign her thankless post. Her superiors will try to dissuade her. “I’m sorry,” she will say. “This isn’t education. It’s crowd control.”

A week later, she will land in Tel Aviv, from where she will travel by land to Qalqilia. By the time she reaches her destination, she will have spent five hours flying from London to Tel Aviv, and a disproportionate eighteen hours travelling the short distance from Tel Aviv to Qalqilia. To Karim. Karim behind The Wall.

Baghdad Café

“THIS is BOND STREET. The next station is Marble Arch. Please allow passengers to get off the train first. Please move right down inside the carriage. Please take up all available space inside the carriages. This train is now ready to depart. Please stand clear of the closing doors.”

On the tube, Kagiso notices a picture of a family strolling on an idyllic private beach. It is an advertisement for a credit card company offering an exotic holiday on an exclusive island for a lucky winner and nine people of their choice. On the golden sands of the beach, someone has scribbled:

‘The world is not your private holiday destination. People live here and they probably don’t have access to this beach.’

“This is Marble Arch. The next station is Lancaster Gate. Please stand clear of the closing doors.”

They exit the station and step out onto the throng of Edgware Road on a Saturday night, four lanes of traffic, a huge crowd waiting to enter the cinema complex, bustling pavements, busy restaurants.

“Many Londons,” Katinka says, “and if Brick Lane is like the Meghna flowing through its east, then this is the like the Euphrates, or the Tigris, or the Nile flowing through its west.”

A little way up the road, Kagiso follows her into an elaborately decorated café, filled with scented smoke and intoxicating music.

“Woah!” he exclaims as the waiter leads them to the alcove in the corner behind a mashrabeya screen. “What is this place? Are we still in London?”

“Do you like it?”

“It’s... It’s like I stepped through the glass doors and into The Thousand and One Nights. How did you come by this place?”

“Issa’s hangout. And the last place I saw him.” A waiter approaches their table. “I’ll tell you later.”

She places their order in Arabic. “A pot of mint tea and two shisha... Apple, please.”

“I’m impressed,” Kagiso nods when the waiter has left.

“Don’t be. That’s the only sentence I’m fluent in, because I say it all the time. The rest of my Arabic is still pretty dire.”

“I’m sure it isn’t.”

“All conversations I have, whether it’s about the past or the future, they all still happen in the present tense. I find the conjugation of the verb in Arabic incredibly difficult.”

“And people understand?”

“Mostly, but I could do better,” she admits. “Of course, I prefix the past with yesterday, even if I’m talking about ten years ago, and the future with tomorrow, even if I’m talking about next year; not very sophisticated, I know, but mostly people appreciate the effort.”

“And can you read and write?”

“I’ve just about cracked the alphabet,” she says, smiling broadly. “I’m still at the c-a-t, cat stage. So let’s say that I can decipher rather than read.”

“So what does this say?” he says, pointing at the menu.

“That says Baghdad.”

“Well, that was pretty fluent.”

“I’ve had a lot of practice with that one too. It’s been on there constantly these last few months,” she says, pointing a finger over her shoulder at the giant screen behind her.

He introduces another round of the game they have been playing randomly during the course of their ambling afternoon - the game he taught her during that first shared drive to Cape Town, all those Februarys ago, with Issa’s deep, reticent silence driving them through the hot Karoo.

“Marianne Sagebracht, Jack Palance and CCH Pounder? That’s a hard one.” She raps her fingers on the table and screws up her eyes as she tries to guess the film in which the three actors appeared.

Pleased with his challenge, he reclines in the plush sofa and smiles, blowing out large plumes of apple-scented smoke.

“Is it recent?” she asks.

“No.”

“Marianne Sagebracht?”

“Sexy woman. Fat is beautiful.”

She shakes her head. “Don’t know.”

“Clue?”

“Clue... You’re sitting in one.”

“An arabesque sofa?”

“Not the sofa, the place.”

“An Arabic coffee shop?”

“Warm.”

She repeats the information he has given her, “Jack Palance, not recent, Arabic coffee shop,” and then opens her eyes wide with excitement, as a child would, to indicate she’s hit on the answer:

“Lawrence of Arabia!”

Kagiso chokes on a lungful of smoky laughter. “Still as crap as ever. You haven’t got one right so far!”

“That’s because you keep coming up with the most obscure films.”

“You give up, then?”

“Ja, tell me.”

“Bagdad Café!”

“Bagdad Café?”

“Yes, Bagdad Café.”

She remembers. “Café in the bundus?”

He nods.

“Gosh, that takes me back. Surreal film? Really haunting theme tune? I can almost hear it now.”

“Callin U,” he says.

“That’s right.” She struggles to hum the tune.

He helps her out.

“Anyway,” she says, slapping his wrist, “how was Arabic coffee shop supposed to be a clue?”

“Katinka!” he sighs, with a tone of mock exasperation, and points to the same menu in front of her.

She sucks her teeth and slaps her palm to her forehead. “Baghdad Cafe... Very good!”

“Baghdad, we used to call it. Meet you in Baghdad. Sometimes I’d get texts from him – ‘Comrad! Smokin in bagdad. Wair r u? Join me!’ Once, he texted me in the middle of the night, oblivious of the time. I was really pissed off, and sent a text back saying – ‘In bed! Iv got 2 teach 30 bastad brats in da am.’ But, being Issa, he had to push it even further:

‘An on fone means u not ntyly unavlbl.’

‘Im vlbl 4 emgncis only! Now Fuk off!’

He didn’t.

‘In bagdad dis is an emgncy. Fuk da bastad brats. Kids r dying here. Get u gat ova here asap. & Fuk lemonde – we r all afghanarabs now!”’

“What was he doing here in the middle of the night?”

Again she points over her shoulder at the enormous screen. “Watching the war on that.”

“What did you do?”

“I couldn’t get back to sleep, so I thought, fuck it, and jumped in the car. By the time I got here, everybody was gripped. The place was packed out, with thick fumes of smoke hanging in the air. It felt as though I had driven across London and into Baghdad itself. The waiters were all standing in a group facing the screen, their backs towards the door. They didn’t turn around to meet me when I walked in. That one,” she says pointing discreetly, “held an empty tray to his chest.”

“Issa wasn’t in our usual seat, so I had to search among the dazed observers to find him. It was a strange feeling. The whole room was caught up in the screen – the shock and awe of the bombs, the explosions reverberating around the world, all the way here, into this room. It felt as though I was walking through a war, looking for my friend amongst the dazed and stunned.

“I found him over there, at that table behind the banister, pipe in mouth, chin to chest, staring at the screen. On his T-shirt was written: ‘I am a standing civil war.”’

Sit down. Come see the view from underneath. This is what the descending heel looks like – the soles of George and Tony’s feet.

“I squeezed in next to him.”

These bombers left Britain as people here were sitting down to tea.

“He gave me the mouthpiece.” She puffed her pipe. “Have you ever seen a real war projected live onto a screen the size of a fucking Piccadilly Circus billboard?”

They stare through the window at the pavements now crowded with late night strollers. The waiter replenishes their drinks, the sabby stokes their pipes.

“It was here, in Baghdad, that we first met when he came to London. He was sitting in his favourite seat, where you are now, smoking a shisha pipe. I was quite nervous, but of course I pretended not to be.”

He frowns. “Why were you nervous?”

“I was intimidated by where we were meeting. Jy moet onthou, ek is ’n plaasnooi. I thought it a strange place for him to suggest. And when the waiter brought the damn pipe he’d ordered for me to the table, carried high through the air, and then set it down beside me in an elegant bow, like a ceremonial offering, I had no idea what to do with the damn thing, so I just puffed it like you would a cigarette. Of course once Issa told me to, ‘trek soos ’n bottle kop,’ I was away and never looked back.”

“Why were you intimidated by this place?”

“I’d never been out on Edgware Road. I guess, like a lot of people, I saw it as rich Arab turf. It would never have occurred to me to socialise here – I didn’t know what that entailed. But look at me now; a regular who can’t get enough. When I told a friend that this is where I was coming, she warned me to be careful, said I might get rolled up in a carpet and smuggled into sexual slavery.”

He smiles.

“I said I wouldn’t be that lucky.”

His smile turns into a laugh.

“Yes, I laughed too. But I don’t think it’s funny anymore.”

He moves around awkwardly in his seat. “Why?”

She shrugs. “Now it makes me cringe to think that I, an Afrikaner, the victim of so much stereotyping, could have done the same to others. It makes me think of Afrikaaners and Arabs as brethren. The last of the Mohicans. The two tribes it is still acceptable to denigrate and berate.” Her thoughts fly to Karim, and to her friend; she never told her about him, knew she’d never understand, didn’t want to hear her sexually-charged references, doesn’t see that friend anymore. She drinks a deep inhalation causing the water in the pipe to gurgle and boil as in an agitated teapot. When she has filled her lungs, she releases a huge cloud of smoke, like a dragon, into the air, thick and fragrant and white, dense enough to hide her face and, for a moment, to cover her sorrow.

She reaches for her phone – “The next day I got a text from him” – and hands it to Kagiso. ‘Tnx 4 cumin last nite. Wen we achievd & da new world dawnd da old men came out again & took our victry to remake in da liknes of da 4mer world dey new. Read Anil’s Ghost, the last sntnc on pg 43.’

Kagiso puts down the phone.

“That was the last I heard from him,” she says. “I never saw him again.”

London N4

WHEN KAGISO FIRST SAW ISSA’S address, he took N4 to be the postcode for London: Finsbury Park, N4, Piccadilly Circus N4, Covent Garden N4, Buckingham Palace N4. London N4. Now, walking around the area, at the end of his stay, he shies away from the memory. How little I knew.

He moves in and out of the station, as if exploring a maze. That was what it seemed like when he first arrived. He was sure he would never find his way and expected to get terribly lost.

“Customer information. Please do not leave your baggage unattended. Customers are reminded that smoking is not permitted on any London Underground train or platform.”

Now he sees the tunnels as they are – simple, like a T with staircases descending down from the vertical branch to each of the platforms. Right for the Piccadilly Line which, tomorrow, he will take, westbound, to Heathrow. (Katinka is insistent that she will drive him as it is a Saturday, but he would prefer to slip out of London, quietly.) Left for the Victoria Line to Brixton – the name reminds him of the Brixton Murder and Robbery Squad near downtown Johannesburg – the Brixton Murderers and Robbers Squad, as they used to call it. Detainees would end up at John Vorster Square slipping accidentally and falling through open windows to their pavement deaths far below. Oops.

“That shit still happens here,” Katinka had said. “And Brixton Police Station is notorious for it.”

The perpendicular tunnel leads to the bus terminus and Issa’s flat in one direction, and in the other to the mosque, with the silent minaret. A phone booth at this exit is covered with stickers: ‘Read Chomsky’.

Frances was right. It is all boarded up, all the ground floor windows and the door covered up with corrugated iron. It strikes him that this is the only time he has seen corrugated iron in London – the metal out of which nearly all South African shanties are built, the metal of his grandmother’s shack before Ma Gloria had the walls bricked.

He imagines the dark emptiness inside the mosque, the deserted corridors, the quiet prayer hall full of unsaid supplications, the dusty, moth-eaten carpets.

He hears just the ends of sounds, the silence after shoes have been kicked off, the last drip from a tap in the ablution fountain – plop – the hush that follows bending bodies and folding cloth when the straight lines of worshippers have fallen to their knees, foreheads to the ground.

Like at Issa’s flat, when he first opened the door. He was sure he’d heard the shower being turned off. He paused in the doorway, thrilled. Plop. He’s back!

“Issa!” he shouted, dropping his bag. He ran into the bathroom. But there was nothing, just a dusty cobweb dangling silently from the dry showerhead.

The excitement hadlasted only a moment, but the disappointment was crushing, ultimate, like Vasinthe’s sinking feeling in the park when she realised that Katinka, in fact, knew nothing.

He slid down the wall, sank into his knees, and wept.

“You’re back!” an old voice exclaimed in the doorway.

He looked up and saw the anticipation fall from her face like a mask and crash into pieces on the floor, like it did from Ma Vasinthe’s at the airport, when she realised the missed call wasn’t from Issa.

“Oh,” the old lady said, not able to conceal her disappointment.

He rose to his feet. “I’m Kagiso. I’m here to pack up his things.”

“Come with me,” she called, turning away from the door. “I’ll get you some breakfast. There’s nothing in there.”

He raises his camera to the disused building. Through his lens, he sees a sticker on the padlock by the gate. When he has taken the photographs – the windows covered in corrugated iron, the silent minaret, the locked gate – he crosses the road to read:

To those against whom

War is made, permission

Is given (to fight), because

They are wronged; – and verily,

God is Most Powerful

For their aid; –

(They are) those who have

Been expelled from their homes

In defiance of right, –

(For no cause) except

That they say, “Our Lord

Is God.”

Qur’an S. xxii, 40

Vasinthe and Gloria

ONE SPRING MORNING IN EARLY September, when Vasinthe gets home, she finds that Gloria has moved her seat, as she has done for three decades, from its winter position next to the stove to its summer position by the door. A new season has been ushered in. Comforted by the continuance of this small tradition, Vasinthe smiles. Soon – always at otherwise unobserved Diwali – they will spend a weekend cleaning the house. Cupboards, wardrobes and bookshelves will be unpacked and scrubbed – old clothes and utensils set aside for delivery to a destitute women’s shelter in Braamfontein – curtains changed, windows cleaned, carpets steamed. The operation will commence on a Friday afternoon. They will work late into the night and start again early the next morning.

When the boys were at home, they each had their allotted roles – men’s hands can clean as well as women’s. Issa always participated fully, almost with relish, offering help elsewhere when he had finished his own chores. Kagiso had to be goaded. All weekend, they’d eat convenience food: fish and chips, microwave dinners. By Sunday afternoon, they’d start rushing towards completion, like the fast forward sequences that come towards the end of makeover programmes. On Sunday evening, Vasinthe would drive them to a roadhouse for burgers and milkshakes. When they returned home, they would collapse into bed, exhausted, in their spotless house.

But this year, Vasinthe and Gloria will be less efficient. They will call an end to Friday without having completed half their usual tasks. On Saturday, they will start late, half-hearted and listless. By the middle of the morning, Gloria will mention two young girls who are in the neighbourhood in search of work. Vasinthe recruits them without question. She leaves Gloria to supervise them while she retreats to her study. She starts to unpack her bookshelves, but slowly works her way towards the wooden Thai box in which she keeps their old report cards, some childhood drawings, some of her favourite hideous souvenirs from school trips. She spends the rest of the afternoon going through the mementos in the box.

“I don’t understand,” she recalls saying to Peter during a recent visit to him on his remote farm. “I don’t understand why he just disappeared. That is just cruel. Why couldn’t he talk to me, to us? Why had he become so alienated, from his own family?”

Peter didn’t look at her. Instead, he lit a cigarette and stared into the rolling green hills of the Eastern Cape. “Distance is a powerful thing,” he said, softly. “It changes people... When I went into exile, all those years ago, I promised myself that wherever I went, my journey would not be over until I returned home, to South Africa. I spent the next fifteen years wishing away my life, Harare, Lusaka, Lagos, London, my fifteen years across the Styx.

“‘Ha, banishment? Be merciful, say death for exile hath more terror in his look, much more than death. Do not say banishment.’ Romeo knew whereof he spoke.

“I don’t think I had a lucid moment during any one of those interminable years. The day after the ANC was unbanned, I finally boarded a plane at Heathrow, bound for home. I couldn’t wait. Only Jacob was there to meet me. He held a sign that said ‘Peter Godfrey’ – in case. His mother was waiting in the car. I walked past the sign. Everything had changed, the airport building, the atmosphere, Jacob – but most of all, me. I couldn’t even recognise myself in the name plate held up by my own son.”

“But Issa wasn’t in exile.”

“No, but he is a child of the struggle.”

“The struggle’s over, Peter.”

He looked at her. “No Vasinthe, the struggle’s never over,” and then turned away. “There is a lot in Britain to alienate a young idealist. ‘Inglan is a bitch’, Vasinthe.” He leaned forward, rested his elbows on his knees and brought the cigarette slowly to his mouth.

“When Jacob was killed, my first reaction was to phone my parents. I picked up the receiver, but I couldn’t remember the dialling code for Port Elizabeth. Couldn’t even remember their home number, so I dialled the only number I’ve ever been able to remember: 0181 926 0215.”

“Who’s was it?” Vasinthe asked.

“Cheb’s – the exiled Algerian journalist who lived in the flat next to mine. We met in the pub on the corner. We both worked nights. Nights were the worst. We both worked them, then stopped for a pint on our way home, to help us forget the night and sleep through the day.” He drops the butt into his empty beer can then reaches into his top pocket. “On the day I left London, he gave me this.” He passes Vasinthe the note folded inside a small plastic sleeve:

Goodbye Peter and good luck. This is what you’ve been waiting for. When a new society dawns in South Africa, as I’m sure it will, spare a thought for those whose struggle continues. Maybe the land of the vast African continent will prove to be a better conductor of democracy than the water of the narrow Mediterranean Sea.

Your brother, Cheb

When she handed him back the note, he returned it to his top pocket, and tapped his heart.

On Sunday, she repacks the books she’d taken down the day before – no dusting, no culling, no alphabetising. In the afternoon, she gives Gloria the cash to pay the girls and suggests that she recruit the more diligent of the two for full-time work, under Gloria’s supervision, starting Monday.

On the table is a bunch of fresh flowers with a little card. In her summer seat by the open doorway, Gloria sets aside the newspaper and watches as Vasinthe opens the envelope:

Fish River

12th September 2003

Good to see you again, Vasinthe. Don’t think I can do the big city anymore, but you’re welcome back here anytime. Thinking of you today. Hope the boy shows up/gets in touch/is found soon. Please keep me informed. Not knowing is killing, but be gentle with yourself...

“They’re from Peter,” she says, laying down the card. “Aren’t they lovely?”

Gloria nods. “It was a huge bunch. I’ve put some in the living room as well.”

“Thank you. I’ll have a look at them later.” She sits down while Gloria pours them each a cup of tea; a ritual that Gloria has insisted upon ever since the boys left for university.

“You have to take a break,” she chided. “You can’t keep going on like this. There’s no need for it any more. Time to take it easy now that they are gone.”

“But -” Vasinthe tried to protest.

“No buts! That university won’t collapse, not one of your patients will die, not one of your students will fail if you have a cup of tea when you get home.”

When they have had their tea, Gloria will chop onions and tomatoes while Vasinthe has a shower. When she returns to the kitchen in a fresh kaftan which Gloria will have chosen, ironed and laid out at the foot of the bed, she will cook the dish that has always accompanied whatever main meal Gloria has already prepared – dhal. “The staple food of India,” her uncle used to say. She loved it as a child and, as an adult, after so much had been forgotten, revised, deliberately abandoned, this simple dish remains her one unbroken link to her convoluted, inaccessible past. It is often all she eats when she is alone and, for all of them, no meal is complete without it.

Before she says goodnight, Gloria asks what she already knows the answer to – if the answer were any different, she’d be the first to know. Still, she has to ask her obsolete question. To ask is to demonstrate hope, articulate possibility. Not to, would be unthinkable.

Vasinthe knows when the question is coming. She could pre-empt, but she waits to hear it. Gloria is now the only one who asks daily, here, in the privacy of their home. She prefers it that way. In the early days, she found the constant questions everywhere she went, invasive. By the time she got home, she felt prodded, tugged at. Every day she wishes that she didn’t have to release her unchanging answer, like a poisoned bow into the air, deadly accurate, slowly fatal. But she accepts Gloria’s acknowledgement and waits to acknowledge it in return.

Having wiped away every last drop of water from the shining kitchen sink, Gloria will wring the cloth tightly and wipe the sink again. Then she will drape the cloth over the draining board, slowly, carefully, as if to defer the moment. She will wipe her hands on her apron and look up at her reflection in the kitchen window – the window through which she peeped, terrified, from the outside, more than thirty years ago. With her back to Vasinthe and her hands tightly clutched in her apron, she will utter her simultaneous question-statement, gently, cautiously:

“No news today.”

Vasinthe will lay down the newspaper and take off her glasses. “Sorry Gloria. No news today.”

This exchange marks the end of their day, like turning out the light.

But, not tonight. “Thirty-three years today,” Gloria adds, still staring at her reflection in the window.

“Yes. Thirty-three years today.”

Gloria turns around. “I’ve made a cake.”

Comforted by the continuance of another small tradition, Vasinthe smiles.

Gloria smiles too. “Would you like a piece?” she asks, puckering her nose encouragingly.

Somewhere and Nowhere

KAGISO WAKES UP IN A BLACK VELVET SKY. The stars hang around him like diamonds, the full moon hovers overhead like a huge pearl. He doesn’t move his head; just stares out through his small oval window at the majesty.

Lethargically, one by one, his senses rekindle and he becomes aware of a gentle, lilting, slightly sorrowful tune in his ear. Katinka knew it. How Frances smiled when she heard the exhumed piece of music earlier that afternoon.

“Would you like me to play it again?” Katinka asked when the tape stopped.

“No, no. I’ll listen to it later. You two had better be off now. This young man has a plane to catch.”

They descended the staircase. When they reached the landing outside Issa’s flat, Kagiso stopped. “I’ll just pick up my bag,” he said nervously to Katinka.

“Need help?”

“No. I’ll manage.”

“Okay.” She tapped him on the shoulder. “I’ll wait in the car.”

He stepped into the room. An amplified silence bounced around its emptiness like a crazed ball in a squash court. The exposed corner where the bookcase used to stand cowered, trying to cover its nakedness like a shy girl. On the bedstead lay the mattress, awkwardly restored, like a shamed adulteress. Only the quotations remained on the walls. For a moment, he thought of just leaving them, but only for a moment. He walked from one to another, picking them off the wall. Like truths from a fortune cookie, reading them, then slipping them into his bulging journal.

Upstairs, Frances listened to the echo of his footsteps ricochet around the empty room. The daunting sound was all she could hear; it crowded out even the sound of the buses in the terminus. She reached for the solace of her red satin pouch.

When he had removed the last quotation – ‘History includes the present’ – Kagiso left the key on the desk as the agent had requested and walked towards the door. He picked up his bag and cast his eyes around the stark room, surveying a disappearance that had now been made complete (everything, he thought, consigned to Alexandria, memory house of the world).

When Frances heard the door close, she turned up the volume on the gentle lilting tune and started a prayer to St Christopher, the patron saint of travellers.

His throat is dry.

When he got into the car, Katinka smiled at him. “Okay?”

“Ja. Let’s go.”

“Nie so haastig nie,” she said mischievously and opened her palm. “See what I made.”

He gawked. “Three!”

“Padkos mos. One for the North Circular, one for the M4 and one for the car after you’ve checked in. Smoke and fly. Vestaan jy?” she joked, laying the spliffs in the recess by the gear stick then stroking them gently with a maternal touch.

He laughed.

“But wait. That’s not all!” she exclaimed, reaching behind her ear. “Here’s one I made earlier, to get us on our way. After all, we have to get from here to the North Circular, you know, en die vader weet, ek is daai desperate vroumens.”

At Heathrow, when it was time to say goodbye, she walked him back into the terminal building. At the entrance to the departure gates, she pulled him back. “I can’t go any further,” she winked. “I’m a sharp object, you know!”

He laughed, and then, when she threw her arms around him, he cried.

“My engel,” she whispered, pulling him tightly towards her. “Kom hier!”

“I’ll be fine,” he said, trying to straighten himself. But it was too late. The floodgates had already opened and all that could be done was to step aside while the months of tears and sobs and snot came gushing out.

She stroked his hair gently and started singing that strange rhyme from home:

“Siembamba mama se kindjie

Siembamba mama se kindjie

Draai sy nek om

Gooi hom in die sloot

Trap op sy kop

Dan is hy dood.”

“I’ve never understood,” he sniffed, “how that was supposed to console a child. I mean, how is anybody supposed to take comfort from being strangled, thrown in the gutter and, how do you say trap in English, stepped on the head?”

“It’s a poem – Langenhoven – from the Boer War,” she said distantly, staring at the huge gun draped around a security guard at the far end of the departure hall. “About Boer children in British camps.”

“Is that so?”

“Yeah. But I guess the comfort’s in the tune, not the words.” She sat up and tapped his head. “Anyway, it worked, didn’t it?”

“Yeah,” he conceded, nodding forlornly. “It worked. Thanks.”

He tries to swallow, but his tongue gets stuck to his palate. He lifts his head above his headrest to look around. The cabin is dim and quiet, just the drone of jet engines propelling them through the night sky. The darkness is pierced here and there by the occasional beam of vertical light from overhead reading lamps. I must have slept through dinner, he thinks, looking down at the book in his lap. He recognised the girl balancing on a stick from Frances’ description of the cover and had set it aside for the journey:

‘... Just when things are improving?’

‘All the more reason,’ said Ishvar. ‘In case things become worse again.’

‘They are bound to. Whether Om marries or not,’ said Maneck. ‘Everything ends badly. It’s the law of the universe.’

He lays the book aside and moves slowly up the inclined aisle towards the galley. He wants to hold an upturned bottle to his mouth and drain it in a quick succession of deep quenching gulps. But satisfaction is to be staggered. On the counter are small glasses of water and orange juice, neatly laid out in rows. He knocks back several of the glasses of water. He wants another, but decides on an orange juice in mid-reach. Then he steps aside to peep through the small window in the thick door.

From this angle, moonlight bouncing off the front edge of the enormous wing, transforming it into a long blade of silver light, evokes an image Frances conjured: “a laser beaming across the Sahara. I often sit here at night and try to imagine what that must look like, a green laser beaming across a clear desert sky.”

Where are we, he wonders? If we’ve crossed the equator, I’ve slept halfway down the world.

A steward comes to replenish the drinks. “Where are we?” Kagiso asks.

“Just above Kano, Sir,” the steward says, pointing at the monitor.

Kagiso looks up dozily. “Thanks, I didn’t see that there.” He focuses, follows the red route of their flight path from London as it snakes its way, like a river of blood, through the African continent in the dead of night: France / across the Mediterranean / Algeria / Chad / Niger...

“I always feel it should be announced.”

Kagiso looks at him questioningly.

“Kano, I mean. It’s exactly half-way. Only another six hours to go. But our passengers wouldn’t appreciate the interruption. You must be hungry, Sir? You slept through dinner. Would you like something to eat?”

“No, thank you. Just another orange juice, please.”

Back in his seat Jimmy Cliff makes him smile. “Any self-respecting traveller should have this track,” Katinka said emphatically as she downloaded it onto his music player. He glances at his watch – 2am, then turns to look out through the window again. At 34 000 feet, the past steps forward into his present.

Muhsin.

He has never actually said the name. He wonders what it will be like if he meets another Muhsin. Would he ever let a Muhsin into his life? He can’t imagine picking up the phone and saying, “Oh, hi Muhsin,” or, “I saw Muhsin for lunch today.” He can’t imagine saying the name with a neutral or loving tone.

One day he was day-dreaming into the kitchen floor when Issa crossed his gaze. He looked up.

“Stop!” he ordered.

Issa stopped out of surprise rather than obedience, a scarred bare foot suspended hesitantly in mid-stride. What?

He sat up in his seat and cleared his throat. “You were born on that very spot.”

Issa looked back at him in disbelief.

“Don’t you get it? You can stand on that spot and say, ‘I was born here.’ How many people can do that?”

Issa looked down at the floor. For a while he just stood there, looking at his feet.

Kagiso couldn’t tell what he was thinking. Then Issa looked up at him – I haven’t looked at it like that – and smiled.

In his window seat, tucked away under a blanket, both somewhere and nowhere, he remembers the first time he got stoned. It was a summer’s night in Cape Town – the best. They were lying on Issa’s mattress, listening to Rodriguez and Pink Floyd:

‘For long you live and high you fly

And smiles you’ll give and tears you’ll cry

And all you’ll touch and all you’ll see

Is all your life will ever be...’

Clearly delighted at the impromptu visit, Issa laughed and joked, even let him in on a few secrets. They talked through the night, but in the morning returned to their separate lives.

After showing him the new library building, Issa walked him to the main gates on Modderdam Road. They sat on the curb, strangers once more, and waited in silence for a taxi that would take him back to the lush southern suburbs – back to the idyll of Rondebosch with its book shops, wine bars and frozen yoghurt parlours – back to UCT with its occasional vogue demonstration, but otherwise mostly undisrupted academic routine.

Please don’t resent me, Issa, he wanted to say. You had a choice and I’m glad you came here. You would have hated it up there. But I didn’t have that choice. You must know that. And I can’t afford to screw this up.

Issa was scratching around with a stick in the sand that had gathered by the curb. Don’t go back, he wanted to say. We can have another skyf and go back to bed for the rest of the morning. This afternoon we can hang out at the pool. And then I’ll drive you back to Rondebosch. We can have fish and chips at Seaforth – best in town, you’re right – and maybe I can stay over. Tomorrow’s Friday, I only have one lecture.

But neither said a thing. They just sat there on the curb with their heads lolling between their knees, seeking shelter from the already scorching 10 o’clock sun.

When the taxi came, they got up reluctantly – Kagiso dusting his bottom, Issa sticking his hands deep into his pockets and hunching his shoulders around his ears.

Sweet, he said.

“Ja, sweet,” Kagiso echoed.

When he had squeezed into the crammed taxi, the gaatjie, still dangling nonchalantly through the open door, pointed at the horizon in an exaggerated gesture and shouted the command for the driver to continue: “Kap aan, driver. Driver, kap aan!”

Before the taxi disappeared over the brow of the bridge ahead, it occurred to Kagiso to turn around and wave, perhaps gesture a phone call, or, with tweezed thumb and forefinger to puckered lips, a joint. But he was too late; all he saw was Issa swing around on his heel and start walking lazily back towards the main gate.

Kagiso readjusts his neck pillow. Despite all the years before, and all the iconic events that were to follow, that arbitrary, insignificant moment has endured to become his most vivid memory of Issa, perhaps because it is also his most lasting qualm. Issa must have stood there on the pavement while the taxi drove away, watching it recede, waiting for him to turn round. Kagiso still shies away from the memory. It is his trifling tragedy. It was the sudden unexpected recollection of this moment – his enduring petty regret – that had distressed him at Heathrow.

The previous morning he had returned to Jan Smuts House following a sociology tutorial. ‘The lunatic is in the hall.’ The cleaning ladies had taken over the place: trolleys, stacked high with clean bedding, were parked in the corridors, wastepaper baskets were being emptied into huge black bags, everywhere the smell of disinfectant. He couldn’t decide whether the handsome old residence reminded him of a hotel or a hospital; in the lofty ceilings, the stone pillars, the ivy and courtyards – grandeur, in the fittings, functional simplicity in the furniture. When he got to his room, he locked out the cleaning ladies and skipped classes for the rest of the day. That evening he would jump into a taxi to UWC to see Issa.

In the tutorial, Dr Johnson had presented them with an article from a prescribed text and asked him to read. For the first time, that morning – as he read out loud about the effects of the calculated, rational brutality of the homeland system, Kagiso contemplated the circumstances by which privilege had come to be a part of his life. Later, sitting in his window seat at Jan Smuts House overlooking the Cape Flats, the raw details of life in the Bantustans – his grandmother’s life – meticulously set out in his lap, he felt hollowed out, as though Dr Johnson had held his life up to the class and torn it into a thousand pieces before flinging it across the desk.

The grainy black and white sequence and the noise of the antiquated projector fill his head as he considers his mother as a young rural woman, walking from house to house in search of work in an affluent ‘coloured’ suburb in Johannesburg.

As the sequence progresses, it turns slowly into colour. She knocks at closed doors, like the insistent cleaning lady in the corridor outside. Eventually, she knocks at Ma Vasinthe’s door. He tries to reconstruct the sort of conversation they would have had.

The noise of the projector fades and he can hear his mother’s voice speaking from the past, but only faintly, a bubbly underwater sort of voice, like the Highlander’s at the bottom of the lake when he realises that he is immortal. He can’t imagine his mother saying the word, but she must have, at least on that first day, said it:

“Madam, I’m looking for work.”

He tries to say the sentence, but it feels as though his tongue will explode. It sticks in his throat, this unutterable sentence, yet, it is certainly what his mother must have said upon first meeting Vasinthe.

Knock knock. “Cleaning.” Knock knock.

–

Knock knock. “Kagiso?” Knock knock. “I need to clean your room.” Knock knock... The game would start with a knock at the door. Ma Vasinthe would look at Gloria who would rush the boys into hiding, while Ma Vasinthe counted slowly and went to answer the door. With each game, their hiding places grew more and more elaborate: in Ma Vasinthe’s secret bathroom behind the built-in wardrobes in her bedroom, behind the geyser in the roof. Once Ma Gloria even took them to hide in the neighbour’s kitchen, where they ate cakes and biscuits, Issa refusing his place at the table, refusing the glass tumbler and plate that had been set out for him, joining Ma Gloria and Kagiso on the step outside the kitchen, drinking from the dented tin mug given to Ma Gloria, waiting for Ma Vasinthe to find them. Ma Gloria had thrown them over the back wall, before jumping over the wall herself and spraining her ankle. Once, when they didn’t have enough time to find a good hiding place, they scrambled under Ma Vasinthe’s bed and waited. That was an eerie round and they didn’t enjoy it very much. It frightened them and, even though Ma Vasinthe said that they were imagining things, they knew that from under the bed they had seen boots. “Lydia,” writes MM Gonsalves, “is tired of trying to make ends meet as well as running from the police. She hates that no matter where one goes, if one does not work and ‘live in’, and does not have a pass, one has to run, because of the danger of trespassing. She begs for a live-in job as she cannot stand the thought of being caught again and of being constantly on the look-out for police.” After that they enjoyed the game less and less... Knock knock. “You won’t have clean bedding if you don’t open the door, Kagiso,” the cleaning lady shouts.

“Kagiso?”

“Please,” he begs in Setswana, “leave me alone. Please.”

‘You lock the door

And throw away the key

There’s someone in my head but it’s not me.’

When he wakes, darkness is creeping up the foot of the mountain below him. For a while he doesn’t know who he is and, in this strange twilight, can’t figure out where he is. He is gripped by fear and sits up, looking around, like a hostage waking for the first time in his cell.

Bit by bit, the details of his room emerge from the fading light. I’m Kagiso. I’m in my window seat.

He yawns and lifts his arms above his head. But in mid-stretch he sees the article on the sill beside him. His yawn stops, leaving just a gaping mouth, the pleasure of the stretch drains from his muscles, leaving just a contorted body.

He remembers who he is. I am Kagiso Mayoyo. I grew up in Johannesburg but I was born in Taung, a small village in Bophuthatswana, a small village in the Republic of Bophuthatswana, the homeland of Bophuthatswana, the Bantustan, Bophuthatswana. The reserve, Bophuthatswana.

‘The lunatic is in my head

You rise the blade, you make the change

You re-arrange me ‘till I’m sane.’

And then, while the far-off muezzin calls the faithful to the last prayer of the day, the reconsidered snippets, the re-interpreted half-truths, the unfathomable whispers, the edited histories, the received ideas all start to fit neatly into orbit around the morning’s reading, piece by recast piece, like blocks in a well-played game of Tetris, until, a new picture emerges, boom, like a kick in the – Along with the hollow relief of the realisation that his mother never would have uttered that underwater sort of sentence.

At least not to Ma Vasinthe.

From his window at Jan Smuts House, it is not the Cape Flats lit up against the night sky he sees, but a spring morning in Johannesburg, 1970, now replaying itself in vivid cinematic colour with deafening sound.

He sees Ma Gloria walking down the road. He is himself only two months old, the bundle strapped in a blanket to her back. He sees the houses on their road, and, for the first time, the neighbours who would have turned her away.

He sees her eventually walking down Ma Vasinthe’s driveway. The new film now deviates from the minimalist black and white version of his childhood because Ma Gloria, he now knows, first entered Ma Vasinthe’s house by the back door. But the back door is not visible from the driveway and, on her first visit to the property, she would have had no way of knowing where it was. Not unless something happened that drew her attention there. A noise? A shout? A crash?

He sits up, draws together, finally, the words of the eternal, never-formulated riddle, asks them of the approaching night: how does it happen that a woman like Ma Vasinthe, a doctor, obsessive about schedules, comes to give birth on a kitchen floor?

In his revised film he sees Ma Gloria cautiously approaching the back door. But Ma Vasinthe doesn’t open the door. She isn’t even standing in the doorway. Where is she? Ma Gloria puts her face towards the kitchen window, her hands at her eyes like blinkers to shut out the light. He shuts his eyes against the sight.

The woman falls to the floor. The man looks up and sees the witness in the kitchen window. He turns away and runs. The woman calls his name. Kagiso hears the name, not called out as a plea for help, but as Ma Gloria has always said it, with a hiss of contempt: Muhsin.

Like a kick in the –

Guts.

He jumps from his seat and runs out of the building and into the car park. Once outside he doesn’t know where to go, except that it is easier to run down the mountain than further up it. So, like water, he follows the path of least resistance, leaping down the stairs at the war memorial, then tearing across the rugby field and through the underpass under the M3.

When he trips on the landscaped lawns outside The Woolsack, he doesn’t try to stop his fall – just allows himself to tumble and roll down the mountainside all the way to Lover’s Walk, where, landing on his feet, like a cat, he continues his sprint. Hares across Main Road without stopping to look for traffic and, at the Mowbray taxi rank on the lower slopes of Devil’s Peak, he dives into a departing taxi, heading east down Klipfontein Road - white in the west, black in the east, Coloured and Indian in between – across the Cape Flats, bound for Bellville: Athlone / Gatesville / Vanguard Estate / Surrey Estate / Manenburg Police Station / Heideweld / over the bridge onto Modderdam Road - coloured in the west, white at the east / Valhala Park / Bishop Lavis / Elsies River / Little House on the Prairie / the graveyard / Belhar Station / UWC.

“Kap aan, driver. Driver, kap aan!”

In the taxi some factory girls natter ceaselessly in Afrikaans over a bag of shared chips, the smell of vinegar mixing noxiously with the heady scent of cheap perfume:

“They say mos that she’s sleeping with the manager.”

“Really?”

“So I hear.”

“I don’t believe it. Who told you?”

“Rashieda, and if she say so then it must be true because she mos know everything that happen in the factory.”

“Ja, you can say that again.”

When his heart has stopped pounding and he has caught his breath, he starts to regret his impulsive decision to visit Issa. What if he isn’t there? It’s been weeks since they even spoke. What will he say? Why has he come to visit? What story will he tell?

“But with him? What does she see in him?”

“Money, baby. Money.”

“Hoer.”

“And white skin, don’t forget.”

“Jagse slet.”

“Ja. Just you wait, I’m gonna ask her tomorrow how do white piel taste.”

“Why you want to know? You want some?”

“Who? Me? Sies!”

He decides that he can’t go through with it, that when he gets to UWC, he will cross the road and immediately get a taxi back to Mowbray.

“Wait, let me tell you this before I get off. My ouma darem ma made us laugh last night, hey! We was watching that police raid of that hostel in Guguletu, so she shouted at the TV, ‘Ja, catch the trouble makers, but it’s that ringleader, Amandla Awethu, that take over our children’s heads so and make them act like kaffirs that I wish they will also catch and put in jail.”’

The girls laugh raucously, but muffle their hilarity when one among them sneakily draws attention to Kagiso.

At the main entrance to the university, he squeezes out of the taxi and crosses the road to wait for a taxi heading back to Mowbray. But he immediately becomes aware of the casspirs lurking in the shadows under the tall trees and, not wanting to appear suspect, proceeds casually across Modderdam Road and into the campus.

Inside, he asks for directions to Ruth First. As he approaches the hostel, he sees Issa standing outside the entrance hall with a group of friends. His gestures are loose and generous, frequently punctuated with hand-clapping, finger-snapping and air-punching. From time to time, agile bodies double over in laughter.

Kagiso doesn’t approach them but waits on the low wall beside the pathway, mesmerised by the sight of an Issa he does not know.

When Issa breaks away from the group, Kagiso gets up and, with a deep breath, follows him, at a distance, to his room. He watches the carefree, relaxed saunter. Everybody he passes, knows his name:

“Ek sê, Issa, my bra!” they exclaim, knotting hands and arms in elaborate handshakes. “Hoesit, my broe?”

Kagiso decides not to say anything. It is not his place. Besides, Ma Vasinthe may already have told him herself. That would explain Issa’s unending devotion to Ma Gloria, and hers to him. It will be up to Issa – if he knows, if he wants to – to raise it.

Take a seat, Issa says, pointing at the mattress on the floor. Kagiso kicks off his shoes and sits down, knees raised, his back against the wall.

Issa retrieves a small wooden box from the drawer in his desk and throws himself down on the mattress beside Kagiso. What’s up?

“Not much,” Kagiso shrugs, awkwardly. “Just wanted to say hi.” He watches Issa empty some of the contents from the box onto a vinyl album cover, purple. He shakes the cover so that the tiny seeds go tumbling back into the box. He transfers the dry leaves carefully into his hand, drops the album cover between them on the bed and gathers the leaves, gently, into a neat line in his cupped palm. Then, in a deft movement, he transfers them from his hand to a blade of thin white paper, which he rolls and licks and lights.

Kagiso picks up the album cover while he thinks of something to say. On it, a pyramid refracts a single beam of white light into a rainbow of colour. “Nice cover,” he says, laying it down.

Brilliant album. Want to hear it?

“Yeah, okay.”

Here, hold this. Issa gives him the joint, takes the vinyl record from the sleeve and walks over to the turntable.

Kagiso holds the joint in his hand, its thick, pungent smoke, swirling in front of him like a charmer’s snake.

Issa turns around and, with outstretched arms, starts to sing to him:

Breathe, breathe in the air

Don’t be afraid to care

Leave but don’t leave me

Look around and choose your own ground

For long you live and high you fly

And smiles you’ll give and tears you’ll cry

And all you’ll touch and all you’ll see

Is all your life will ever be

Issa flops back onto the bed. Before handing him back the joint, Kagiso brings it to his lips and inhales.

The Last Night

KATINKA IS IN BAGHDAD CAFÉ, drinking mint tea, smoking shisha. She has driven here from Heathrow, taking the M4 back into central London, driving against the flight path on her right, a queue of planes waiting to land hangs for miles into the distance. On the dreaded elevated section of the motorway, as she approached the top of the steeple, the bulk of the church out of view below, she tightened her grip on the wheel and divided her concentration between the stream of traffic in front and behind, the lorry passing on her right, the steeple-marked edge on her left; whenever she hears the expression ‘going over the edge’, it is this short, congested strip of elevated motorway that always come to mind. When the traffic came to a halt with the approach to the Hogarth Roundabout, she released her grip, stretched her fingers and lit a cigarette. She continued east along the Great West Road, through Hammersmith, Kensington, Knightsbridge. At Hyde Park Corner, she turned left and headed up Park Lane towards Marble Arch. That was when she heard the boisterous singing coming from Hyde Park:

...The nations not so blest as thee,

Shall in their turns to tyrants fall;

While thou shalt flourish great and free,

The dread and envy of them all...

She can’t think of a time when she didn’t know the anthem; like Die Stem, it has been there all her life, all her history, relishing exclusion, celebrating subjugation. The tune sparks tangential, flash-by memories; a dislike of it and a continued reverence, a persistent tenderness, for a little corner of her past which she cannot – despite the protestation, the spurning and the never-to-return walking away – bring herself to surrender:

At school, she loathed excursions, which always included long, solemn visits to national monuments around the country –

Die Taalmonument (the world’s only monument to a language) in Paarl, Die Vroue Monument in Bloemfontein, Die Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria, Die Groote Kerk in Cape Town. She’d feigned sickness whenever one of them loomed, or deliberately ambled to school so that she would miss the bus.

Except when the opportunity arose of a trip to Kimberley. She had just read The Diary of Anne Frank and tagged along as they visited the Mine Museum – “This is the biggest man-made hole on earth. Work here ceased on 14 August 1914, by which time 22,5 tons of excavated earth had yielded just 2 722 kilograms of diamonds” – Magersfontein – “It was in this battle that trenches were first used in modern warfare” – the McGregor Museum – “this grand building was once the residence of Cecil John Rhodes.”

But it was at the nondescript site on Long Street, in front of the big church, that she took up her place in the front row, the Diary tightly clutched in her hand. “This is the site of the first concentration camp on earth, designed by Lord Kitchener for the imprisonment of Boer women and children during the Anglo-Boer War, the first war of the 20th century, the first modern war. A total of 26 000 women and children died in these camps. In the single month of October 1901, when the camps held 113 606 people, there were 3 156 deaths. Let’s have a minute’s silence to remember their sacrifice.”

“Is that it?” she wanted to call out as they boarded the bus. “Come back! This place is not just about your tribe and the cruel indignity it suffered at the hands of the British. It’s not just about the hundreds of black people who, by the way, also died in the camps.

“It’s about the world, because on this spot, on this very spot, the British initiated a system of incarceration which, fifty years later, would be refined with deadly efficiency on the other side of the world – a system of extermination in which ultimately millions would be led to their gasping gassy deaths and for which this site, this very spot, provided the blueprint, the prototype, the inspiration.

“Don’t you see?” she wanted to plead, “Our people, the ‘Volk’, weren’t the only victims here, they were only the first.”

‘... To thee belongs the rural reign;

Thy cities shall with commerce shine;

All thine shall be the subject main,

And every shore it circles thine...’

Frances mutters her usual irritation as she always does at this point. It annoys her that so many reasonable people will sing along, flushing proudly, without any sense of irony or reflection, teaching their children to sing along too. Not just the blatantly supremacist, but ordinary, likeable people, informed people, liberal people. Catholics.

“But there have to be limits, Frances,” Father Jerome once insisted. “Countries have to set limits on the number of immigrants they can accept, otherwise they’d lose their national character.”

What was the use, Frances thought, of countering the priest? He had orthodoxy on his side. But she persisted: “And what about this country’s national character, Father. Was it lost when you and your order came here from France, or me from Ireland?”

“Have you ever thought, Father, about what would happen if the anti-immigration bigots had their way? For instance, would the Holy Family be given asylum in Britain now on the evidence of Joseph’s bad dream?”

The priest shut himself off with arms folded tightly across his chest.

“I’ll tell you what would happen, Father. Next, it would be the Catholics, the Jews, the – ”

“Well that’s just absurd,” the priest spluttered.

“Is it, Father? Is it really? I’ve been around long enough to know that there is no end to their malice. The more you pander, the more they’ll take. With the blacks out of the way, we’ll be next, Father – you,” she said, pointing a finger at the priest, before turning it on herself, “and I. Once again, we’ll be at the bottom of the pile. Remember what that was like, Father?”

When she decided on this route, Katinka had forgotten that this year, for the first time, the last concert of the season is being relayed to Hyde Park from the Royal Albert Hall up the road. This anthem means it must be nearing its end. She doesn’t want to get caught up in the flag-waving crowd when it leaves the park, so she increases her speed up Park Lane.

‘... Thee haughty tyrants ne’er shall tame,

All their attempts to bend thee down

Will but arouse thy generous flame;

But work their woe, and thy renown...’

She recalls the moment when the old flag came down on the old country – to her, a sublime, ‘at last’ moment, everybody suspended between the eternity that had passed and promise of what was yet to come. She looked at the expectant faces around her, unknown faces in a sea of faces that had gathered on the Grand Parade, the very spot where once a castle, without consultation, had been built. Three hundred and forty-two years, she counted, finally draw to a close – wrong years, dark years, evil years, driven by the philosophy behind songs like these, all of them now, finally, behind. She felt the uniformed, straight lined, saluting little girl she once was step out of line, throw off her badges and run towards this stateless moment: no flag to wave, no anthem to echo, no eternal enemy against which to perpetually defend, no God-chosen nation for which to die in gory glory. She looked up at the empty flagpole, the muted brass band, not wanting the stateless moment to end. If she had to spend an eternity anywhere, it would be right here, now, in this moment.

In the park, the bellicose crowd has started the final verse. Katinka turns up the volume on her stereo to try and shut out the sound: ‘So here’s a toast to all the folks that live in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, El Salvador / Here’s a toast to all the folks living on the Pine Ridge Reservation under the stone cold gaze of Mount Rushmore...’

But her sound system cannot compete with the patriots now in full swing. Even when she has rolled up the windows, she can still hear the final chorus:

‘Rule, Britannia! Britannia, rules -’

Frances switches off the TV. The flags, she thinks, seem to grow more numerous every year, the singing more triumphalist. And this year, after everything that has happened. She shakes her head. The arrogance of it all, the hankering. The embarrassing self-deception.

She steps out into the night and settles into the driver’s seat. Not many more of these remain, she thinks. At this time of year, she always believes that the summer will linger. It is still too much in evidence – the trees are green, the beer garden in the pub downstairs is still in use, there is laughter in the street – to imagine that in only a few weeks, everything will have changed: the evenings will start to draw in, the leaves will turn, the clocks will go back, initiating the long, dark winter months when the streets will be filled with the soulless trudge of coated bodies and booted feet. The thought makes her shudder and she quickly tries to un-think it.

She looks up to the sky. It is a clear night.

‘And dost thou not see that the stars in the heavens are without number, and yet none of them but the sun and the moon are subject to eclipse.’

It doesn’t take her very long to locate the North Star. She’s been practising with the help of the book Kagiso gave her. She can identify all the main constellations and, just to the right of the North Star and slightly above, the location of a new comer. She cannot see it, but she knows it’s there. She has even given it a name.

It did, of course, end – the sublime, stateless moment. When the new flag was raised and the new anthem sung and thousands, millions, cheered, Katinka wiped away a tear; the moment had ended. By the time the new flag reached the top of the flagpole (where the interim quickly – just one patriotic puff, one nationalistic sniff – became the addictively permanent) the endless, limitless, possibilities of the stateless moment had already been diminished.

The waiter delivers another pot of mint tea to her table, while the sabby with his basket of coal diligently stokes her pipe, first scraping away the burnt-out embers then replacing them with five glowing coals arranged neatly in a circle on the tobacco.

“Shukran,” she says.

“You speak Arabic?”

“No,” she says, not wanting conversation.

“How you know this word?”

“We’re all Arabs now,” she says.

“Pardon?”

“Nothing,” she waves. “Just something a friend once said. We’re all Arabs now,” before obscuring her face with a cloud of thick, fragrant smoke.

Closed Chapters

‘My appeal is ultimately directed to us all, black and white together, to close the chapter on our past and to strive together for this beautiful and blessed land as the rainbow people of God.’

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

‘WE’VE GOT STARS DIRECTING OUR FATE.’ The song prompts a name – Robbie – that wakes him. The sky is changing, a familiar African dawn nudging at the horizon, the red trail of their flight path lengthening: DRC / Angola / Botswana... Home isn’t far away. In the half-light, Kagiso starts to feel his way carefully around the past, like a blind man identifying a corpse.