CHAPTER TWO

On a More Personal Note

PHILOSOPHY IN THE LETTERS

Cicero tells only important things.

Michel Foucault, Technologies of the Self

I would not send you a letter so full of myself except that I long to have you understand . . . .

Caroline C. Briggs

AN EXAMINATION of Cicero’s own reasons for writing the philosophical treatises is an essential part of any attempt to understand this body of work. In trying to consider his motivation, however, we are faced with an often confounding multiplicity of goals that he presents in the treatises themselves. He alternately assigns the impulse behind these compositions variously to his desire to benefit his fatherland and fellow-citizens, his need for activity in the absence of a public career that had previously occupied his days, and his desire to find consolation after the devastating loss of his daughter. The differences between these claims make it virtually impossible to take all of the professed goals as equally accurate representations of Cicero’s actual motivation.1 Moreover, the decision as to which claims are to be taken more seriously and which interpreted primarily as rhetorical devices directed at forming audience reaction significantly affects how we understand the production of the corpus. Thus, if one thinks that the main reason behind the mass production of the more technically philosophical works of 45–44 was the need to take consolation in philosophy following the death in February 45 of Tullia, Cicero’s beloved daughter, then the author’s claims that the corpus was meant to be an important contribution to the future of the republic are bound to be taken less seriously, as secondary and rhetorical. Conversely, taking at face value the more state-oriented claims regarding motivation would mean giving less weight to the notion that the works were written as consolation in a time of personal suffering. While it would be naïve, and fruitless, to deny that there was a real multiplicity of reasons behind the creation of a corpus as large and diverse as Cicero’s philosophical works, an attempt to determine which of the reasons the author alleges are more likely to be rhetorical exaggerations, and why, should contribute to a better understanding of the corpus as a whole.

Yet, judging the validity of individual reasons as well as their relative importance is no easy task. Cicero himself never explicitly examines the interrelations among the various motivations that he invokes in the prefaces. In fact, as will become clear in my discussion of individual prefaces in the following chapters, he often leverages mutually contradictory positions against each other when it is rhetorically convenient. Avoiding explicit statements about the hierarchy of the forces that motivate his project was clearly very much to his advantage in communicating with a heterogeneous potential audience. That is, Cicero may have discussed different reasons for writing philosophy in the prefaces to his treatises not because they accurately represented his actual motivations, but because they served an important rhetorical function, helping him to represent himself and his project so as to appeal to his readers. They were, thus, an essential part of the self-justification that the prefaces perform. In addition to Cicero’s need to justify different aspects of his project with different motivational accounts, the variety of potential prejudices in the audience itself no doubt further complicated this representational process, even to the extent of introducing contradictory reasons. Given, then, that the author had a vested interest in obscuring much that was relevant to understanding his motivation in the interest of improving his works’ chances at positive reception, it is difficult to come to any conclusions based exclusively on Cicero’s own claims in the prefaces.

If we conduct our investigation exclusively in the realm of the treatises, coherent arguments can be (and have been) advanced for either of the proposed motivations behind the writing of these works, and little basis will be available for evaluating the strength of these respective arguments save one’s personal inclination and intuition.2 Thus, in trying to do justice to Cicero and his philosophical output, it is important to find a vantage point outside the treatises themselves from which the various competing claims can be evaluated. Such a perspective can be gained by examining the references to philosophy, writing, and intellectual life more generally that are to be found in Cicero’s correspondence. Given the highly rhetorical nature of the letters and, in particular, Cicero’s care in adapting each letter to the perceived expectations of the addressee, the addressee’s own views on these matters will function as constraints on Cicero’s expression, as will the particular persuasive goals that he is pursuing in each individual letter.3 Yet, although we can never know what the historical Cicero truly thought about philosophy’s potential in public, as well as his own, life, we can nonetheless measure the more abstract hortatory claims that the prefaces make about philosophy against the more practically engaged function that philosophy plays in the letters.4

My discussion of the correspondence falls into four sections. The first looks at Cicero’s recourse to philosophy as a deliberative resource in times when important decisions have to be made, and discusses a complex series of interactions that showcases Cicero’s beliefs about philosophy’s potential for improving character. The second examines how he constructs the relationship between philosophy and politics. The third moves to consider his representation of philosophy, and writing more generally, in relation to the traditional division of elite activities between the spheres of otium and negotium. The final section treats the issue of philosophy as consolation and confronts the view that Cicero’s grief for Tullia motivated his philosophical writings.

PHILOSOPHY AS A BASIS FOR ACTION

If we are to evaluate Cicero’s claim that he wrote philosophy as a service to the well-being of the state, one issue needs to be illuminated, namely, the question of philosophy’s ability to actively influence people’s beliefs and actions.5 That is, if the goal of writing philosophical treatises is, by educating men about ethics and knowledge, to change their relationship to the republic and turn them into loyal citizens of a Ciceronian bent, thus improving the condition of the state, then the author must necessarily believe in philosophy’s power to produce such change.6 I will in fact argue that a number of letters from different periods demonstrate Cicero’s persistent belief in philosophy, on the one hand, as a tool that men can use in making decisions with implications for the state, and, on the other hand, as a force that can affect and change an individual’s character for the better. But the way in which philosophy is drawn into Cicero’s deliberation shows development: philosophical models start out as relatively inert references and, as the ever-worsening political situation reveals the failure of traditional structures, gradually become more integrated into practical decision-making.

The letters in which references to philosophical deliberation as a basis for action occur are addressed, not unexpectedly, to men whom Cicero could expect to be generally sympathetic to philosophical argumentation. Thus, the tone is never exhortatory, as it is in the prefaces to the philosophica; rather, the references appear within the framework of Cicero’s providing his correspondents with an account of his thinking on particularly important issues. This presentation not only provides a great point of access to how Cicero perceives the political forces in play on a given issue, but also reveals what types of deliberative resources and strategies he deems relevant to political deliberation at different times. His heightened awareness of his own thought processes and his resulting double function as both the agent and an observer of his own actions lead to his being explicit about what he is thinking and also about how he is framing those thoughts. The resulting layer of built-in self-analysis is extremely valuable: it identifies the deliberative resources he employs at times when important decisions have to be made, and it reveals that his use of particular types of resources is highly self-conscious. The focus of the discussion that follows will be on letters from the period leading up to and contemporaneous with the production of the philosophical treatises that are at the center of this study, the period in which philosophy becomes more central to Cicero’s thinking. I begin, however, by looking at a letter that significantly predates this period; this letter will both demonstrate the presence of intellectual motivation in Cicero’s deliberation before the civil war and allow us to see how his use of this type of deliberative resource evolves over time.

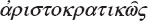

The close of year 60 found Cicero in a precarious position. He had been riding high following his disclosure of the Catilinarian conspiracy in 63, but was not able to consolidate his influence in the changing political landscape. His testimony in the Bona Dea trial made a dangerous and implacable enemy of Publius Clodius Pulcher.7 He looked for support to Pompey, recently returned from the East, but his cautious support for the land bill to benefit Pompey’s veterans may not have been satisfactory in the general’s eyes. Caesar, who was to be consul for the following year, was cementing his relationship with Pompey, and planning to introduce an agrarian bill that Cato and his allies were set to oppose bitterly. Cicero was facing a series of important political choices, the first having to do with the upcoming agrarian bill.8 In a letter to Atticus written during this period, in which he tries to evaluate his political options and think through the likely consequences of each for his career, Cicero makes clear that the method he is going to use for organizing and presenting his thoughts lies in the extra-political, intellectual sphere. This he identifies as the Socratic method, but in fact his discussion ranges much more widely:9

Venio nunc ad mensem Ianuarium et ad  in qua

in qua  sed tamen ad extremum, ut illi solebant,

sed tamen ad extremum, ut illi solebant,  est res sane magni consili. nam aut fortiter resistendum est legi agrariae, in quo est quaedam dimicatio sed plena laudis, aut quiescendum, quod est non dissimile atque ire in Solonium aut Antium, aut etiam adiuvandum, quod a me aiunt Caesarem sic exspectare ut non dubitet. nam fuit apud me Cornelius, hunc dico Balbum, Caesaris familiarem. is adfirmabat illum omnibus in rebus meo et Pompei consilio usurum daturumque operam ut cum Pompeio Crassum coniungeret. hic sunt haec: coniunctio mihi summa cum Pompeio, si placet, etiam cum Caesare, reditus in gratiam cum inimicis, pax cum multitudine, senectutis otium. sed me

est res sane magni consili. nam aut fortiter resistendum est legi agrariae, in quo est quaedam dimicatio sed plena laudis, aut quiescendum, quod est non dissimile atque ire in Solonium aut Antium, aut etiam adiuvandum, quod a me aiunt Caesarem sic exspectare ut non dubitet. nam fuit apud me Cornelius, hunc dico Balbum, Caesaris familiarem. is adfirmabat illum omnibus in rebus meo et Pompei consilio usurum daturumque operam ut cum Pompeio Crassum coniungeret. hic sunt haec: coniunctio mihi summa cum Pompeio, si placet, etiam cum Caesare, reditus in gratiam cum inimicis, pax cum multitudine, senectutis otium. sed me  mea illa commovet quae est in libro tertio:

mea illa commovet quae est in libro tertio:

‘interea cursus, quos prima a parte iuventae

quosque adeo consul virtute animoque petisti,

hos retine atque auge famam laudesque bonorum.’

haec mihi cum in eo libro in quo multa sunt scripta  Calliope ipsa praescripserit, non opinor esse dubitandum quin semper nobis videatur

Calliope ipsa praescripserit, non opinor esse dubitandum quin semper nobis videatur  (Att. 2.3.3-4; SB 23)

(Att. 2.3.3-4; SB 23)

I come now to the month of January and to my political plans, in which matter I will discuss each side, in the Socratic way, but at the end, as his followers used to, will lay out the side that pleases me. It is certainly a matter that deserves serious thought; for either I must strongly resist the agrarian law, in which case it will be contentious, but full of glory, or I must be quiet, which is not so different from going to Solonium or Antium, or I must even help it along, which they say is what Caesar expects me to do, with no doubt in his mind. For Cornelius came to see me, I mean that Balbus, Caesar’s friend. He insisted that Caesar would use my and Pompey’s advice in all things and work to join Crassus with Pompey. Here I would get the following: real closeness to Pompey, and if I want it, with Caesar too, reconciliation with my enemies, peace with the people, rest for my old age. But the conclusion I wrote for book three unsettles me:

Meanwhile the path which from your earliest youth

and as a consul you pursued with virtue and spirit,

continue to follow and increase your fame and praise of all good men.

Since it was Calliope that recommended this to me in that book, in which much was written in a properly aristocratic way, I think I cannot doubt that this must always be deemed the best way: “One omen is best: to defend one’s country.”

The deliberation is presented as formally derived from the school of Socrates; that is, for Cicero, from the New Academy. What Cicero is promising is a rational discussion of the pros and cons of the two positions in similar terms that will result in a preference for one of the two. That, however, is not what he proceeds to do. Instead, he presents three options: resistance, neutrality, and support. Neutrality receives only a cursory consideration that equates it with a voluntary withdrawal from political life.10 Support for Caesar is considered at great length, with the focus on its practical advantages, outlined first by Balbus in terms that are flattering to Cicero in that they highlight his political influence and then, more frankly, by Cicero himself in a way that takes his political status into account but is also concerned with his safety and security. Resistance, the position Cicero chooses, is not discussed with the same parameters in mind. Apart from the brief mention of dimicatio, struggle, that would be involved and that provides a counterpoint to pax and otium, peace and leisure, in the discussion of the advantages to be derived from supporting Caesar’s law, the focus here is not on practical consequences, but rather on the projected external reactions, both the immediate (praise), and the more long-term (glory).

This direction is signaled in the first mention, plena laudis, and is developed at the end of the passage with the support of literary quotations. The form of deliberation followed here, then, does not conform fully to arguing in utramque partem. Instead, the decisive factor appears to be rather traditional: Cicero turns to an exemplum to guide him to proper action. What is far from traditional, however, is the extreme circularity of this appeal. It is not unusual for an outside observer or advisor to recall a man’s earlier achievements in an effort to inspire him to new actions.11 Here, however, Cicero seeks to inspire himself not by looking back on his great deeds, but on a representation of his character by Calliope as imagined by him in a poem that celebrates his consulship. This he presents as an external exhortation, emphasizing the authority of Calliope ipsa, and the normative nature of her address, praescripserit, as well as justifying his inclination to obey her call by the presence of other sentiments expressed  in the poem.12

in the poem.12

Why does Cicero appeal to a philosophical method of decision-making, but then fail to follow through and resort instead to a highly externalized self-image to guide him? While the two modes do not coalesce into a coherent deliberative model, they do share a normative, prescriptive quality, and would thus seem to indicate a desire on Cicero’s part to lock himself into a decision guided by externally imposed modes of thought that he approves of apart from any specific situation. The practical advantages that would accrue to him from supporting Caesar are clearly very appealing, and so it would seem that he needs the force of a philosophical framework and an exaggerated version of himself in a poem of praise to resist them. The ambivalence that he still feels is apparent in the final quote he chooses to state his decision. Hector is here speaking to Polydamas in book twelve of the Iliad. The context surrounding Hector’s noble sentiment is his refusal to listen to Polydamas’ interpretation of the portent of the eagle and the snake, but the reader is likely to remember that his resistance to Polydamas’ cautious advice not to push further towards the Greek ships will ultimately prove disastrous.13 The choice of this quotation thus reflects Cicero’s own ambivalence about the wisdom of his apparently noble choice.14

What about the collection of resources Cicero uses to direct himself to a decision, or, at least, to present the process of his decision-making to Atticus? It is rather eclectic, but the extra-political, nontraditional models dominate and ultimately prevail. Even the traditional paradigm of appealing to an exemplum is employed in a way that is generalized through the use of the muse of history as the mouthpiece, rather than specific, and intellectualized, as it appeals to Cicero the thinker instead of directly summoning Cicero the consul, the agent. This assemblage, though lacking internal consistency, outweighs the practical political considerations on this occasion by virtue of its intellectual pedigree. Cicero goes where the invocation of Socrates and Hector summon him, though well aware of the danger inherent in his choice. The very framework carries weight in that these sources seem to be used deliberately to give him the extra push towards what he sees as a difficult, but honorable decision.

An appeal to intellectual and, more specifically, philosophical resources in deliberation about a proper course of actions is most frequent in the letters of the civil war and Caesarian period. It was a time when the need to make difficult choices in unpredictable circumstances was becoming more common, and Cicero’s need to place his choices of the moment into a larger framework seems to increase correspondingly. The prominence of intellectual and philosophical means in providing this larger framework is particularly significant for understanding his thought during this time. My first example comes in a series of letters addressed to Servius Sulpicius Rufus in late April of year 49, when both men found themselves in a similar situation following the departure of Pompey from Italy and Caesar’s occupation of Rome. In a personal meeting at the end of March, Cicero had refused Caesar’s request to appear in the senate and speak favorably or, at least, to remain neutral.15 Servius, who did attend the meeting, spoke in a manner that was not to Caesar’s liking. The two consulars sought each other’s advice on whether to follow Pompey or remain in Italy. The first letter that Cicero wrote to Servius followed Servius’ inquiry, made through a close friend, as to Cicero’s whereabouts. In the course of the letter Cicero outlines the situation, both personal and political, and presents possible ways in which the deliberation could proceed. The passage central to my purposes follows Cicero’s identification of Servius as the perfect partner for considering the question. Its immediate goal is to explain what makes Servius the right man with whom to deliberate (and to flatter him through the approbation implied in the description). At the same time, the statement’s implications are more general: the sources that Cicero identifies as necessary for correct deliberation can only fulfill their function of flattering the addressee if the addressee recognizes them as drawing on a more general ideal:

nec enim clarissimorum virorum, quorum similes esse debemus, exempla neque doctissimorum, quos semper coluisti, praecepta te fugiunt. (Fam. 4.1.1; SB 150)

For neither the examples of the most renowned men, whom we ought to resemble, nor the teachings of the most learned, whom you have always cultivated, escape your notice.

In this rather brief summary of Servius’ deliberative qualifications, the first element, exempla clarissimorum virorum, refers to the traditional view that what should guide the Roman citizen in his decisions, if he is to achieve fame and immortality, is the mos maiorum, contained in the actions of the ancestors transmitted in history.16 What makes even this part of the statement less traditional, however, is the fact that Cicero puts it on an equal footing with another set of deliberative resources: in the conventional framework, the mos maiorum is all-embracing and self-sufficient; nothing beyond it is necessary to make the right choice.17

Cicero’s second element, doctissimorum praecepta, is a reference to philosophy, and, faute de mieux, Greek philosophy.18 I have already discussed in chapter 1 the difficulty in presenting philosophy as a positive force in Roman public life. Cicero’s struggles with the ingrained perception of philosophy as incompatible with productive service to the state, and, by implication, with the mos maiorum that motivates citizens in that service, will also constitute an important part of my discussion of the prefaces to the philosophica. It is thus particularly significant to find this pairing of tradition and philosophy in his private correspondence as the combination that he and men like him need to act well. That this combination is mirrored by the content of Cicero’s treatises, works that illustrate Greek philosophical thought with Roman exempla, further suggests the importance of joining the two in Cicero’s thought.19

In addition to the treatises themselves, the letters provide an example of Cicero’s blending of the two types of resources, albeit in modified form, in his analysis of his own situation. In a letter to Papirius Paetus composed in the summer of 46 he describes the indignities and uncertainties of life under Caesar.20 In concluding the description, Cicero writes:

etenim, cum plena sint monumenta Graecorum quem ad modum sapientissimi viri regna tulerint vel Athenis vel Syracusis, cum servientibus suis civitatibus fuerint ipsi quodam modo liberi, ego me non putem tueri meum statum sic posse ut neque offendam animum cuiusquam nec frangam dignitatem meam? (Fam. 9.16.6; SB 190)

And indeed, since the records of the Greeks are full of how very wise men endured kingship, whether in Athens or in Syracuse, when, though their states were enslaved, they themselves somehow remained free, shouldn’t I think that I can preserve my position in such a way that I neither offend anyone nor break down my dignity?

What Cicero is appealing to here is a conflation of the two paradigms he offered Servius. Instead of using the examples of great statesmen and the teachings of philosophers, he is invoking what may be termed virorum sapientissimorum exempla. Practicing philosophy well under conditions of tyranny has been elevated to the same exemplary status as active participation in the political process, and is seen as providing a way of transcending the enslaved condition. Greek philosophers here serve as models for a Roman statesman forced to become a full-time philosopher.

Returning to the correspondence with Servius, we see that while the first letter sets out the general parameters of the decision to be made, the following letters, which contain actual reflections on the matter, provide a number of examples of Cicero’s use of philosophical argumentation in the deliberative process. Ad Familiares 4.2.2 (SB 151) frames the discussion in terms of the honorable (honestum, rectum, rectissimum), and the expedient (quid expediat), concluding that the two are identical for those who desire to be honorable themselves (ii qui esse debemus, boni). (Virtually the same terms are used in a letter on the same subject to L. Mescinius Rufus, 5.19.1-2 [SB 152].) The philosophical argument between what is right and what is profitable is at least as old as Plato’s Republic,21 and the identity of the two is uniformly advocated by those who champion virtue as the highest good.22 At the same time, it is significant that we find Cicero using boni in this context. While the term has philosophical currency, its presence in this passage cannot be divorced from Cicero’s continuous politically charged use of boni in promoting his vision of the positive elements within the state.23 The political and the philosophical seem to overlap in Cicero’s thought here. We can see, moreover, how the philosophical can in fact be potentially useful to Cicero’s political goals. While his use of the term in a political context is so flexible as to be almost arbitrary,24 giving boni a philosophical basis by connecting it with the abstract concept of the “good” that can be assumed to have a firm definition within a coherent system of thought in effect creates the illusion that its meaning in political contexts is more stable as well.25

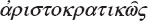

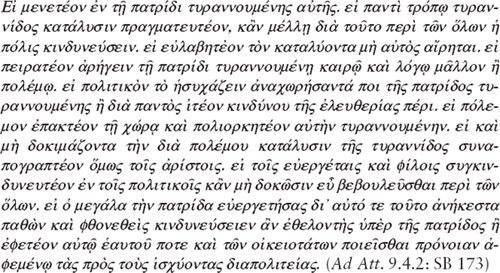

Another letter that preceded the exchange with Servius by a month and a half, Ad Atticum 9.4 (SB 173), shows Cicero himself appealing to philosophy as a way to determine the correct way to act. While any letter penned by Cicero cannot be taken to present the author’s thought in an entirely direct and unmediated way, it is in the letters to Atticus, the man who comes closest to fulfilling the Aristotelian (and the Ciceronian) definition of a friend as alter ego, that we find Cicero at his most sincere.26 The letter starts out with Cicero lamenting the state of affairs that precludes the two friends from engaging in their accustomed discourse (familiariter) and leaves him at a loss for subject matter (egeo argumento epistolarum). He then proceeds to list a series of questions that are on his mind regarding the decision he is facing in view of the conflict between Pompey and Caesar:27

Whether one should remain in one’s country when it is under a tyranny; whether one should work to bring about the overthrow of the tyranny in every way possible, even if on account of it every part of the state will be put at risk; whether one should beware of the one overthrowing (the tyranny) lest he take it upon himself; whether one should try to help his country, which is under tyranny, by choosing the right time for diplomacy rather than making war; whether living in peace having found a place to retire somewhere in his country, which is under a tyrant, befits a statesman, or whether one should instead undergo every danger for the sake of freedom; whether one should bring war upon his land and besiege it, when it is under tyranny; whether even if one does not approve of the overthrow of tyranny through war, one should nevertheless support the best men; if in political matters one must face danger together with one’s benefactors and friends, even if they do not seem to have reached good decisions in all matters; if a man who benefited his country greatly and on account of that very fact suffered irreparable damage and incurred ill-will should invite danger on behalf of his country or one should allow him at some point to take thought for himself and his household, letting go of political resistance against those in power.

The relevance of these questions to Cicero’s situation and the decision over which he agonizes during this time is clear: the reader can supply the names of Pompey and Caesar as the tyrant and the liberator, who may well turn into a tyrant, and will see clearly the reference to Cicero’s suppression of the Catilinarian conspiracy and the exile that followed the great statesman’s benefaction to his ungrateful country. Despite this transparency, a number of features significantly distinguish this letter from other discussions of the current political circumstances in the letters of this time-period.

In the first place, it is noteworthy that Cicero chooses to phrase his questions in a generalized normative manner, instead of openly referring to the specifics. The consistent use of the Greek verbal adjective, an impersonal and abstract way of expressing obligation, emphasizes Cicero’s goal in attempting this mode of deliberation: he wants to universalize the issues so that he can arrive at the most proper decision. As we know, Cicero did in this case follow the philosophical imperative and chose the side to which his loyalty and his sense of right directed him instead of the course of neutrality and safety. He almost immediately realized that it was a disaster in practical terms and left Pompey’s camp as soon as he felt that he had fulfilled what duty required, but, in the years that followed, he remained content in the realization that on this occasion he chose to follow his convictions.

Here, in his quest for the moral imperative, Cicero does not follow the familiar path of Roman tradition that he demonstrated on many occasions in his speeches by recalling to mind how famous Romans of the past had acted in similar situations and extracting lessons from their behavior.28 Thus, his choice of language is significant and conscious: the entire list is presented in Greek, the language proper to the type of philosophical discourse that Cicero is invoking by framing the questions abstractly.29 What we see here is Cicero practicing what he is later going to preach in the treatises: the application of philosophy to decision-making in matters important to the state.30 In those later years, we see Cicero, no longer capable, in his new circumstances, of following the call of virtue, trying to inspire his readers, and especially the younger generation, to incorporate philosophical thinking into their deliberations.

The questions set out by Cicero remind one, in their phrasing, not only of a philosophical search for truth, but also of the kinds of questions posed as exercises in rhetorical declamation.31 And in fact, in the section that follows the list of questions, Cicero tells Atticus that he has been thinking about these issues and arguing opposing positions one after the other (in his ego me consultationibus exercens et disserens in utramque partem tum Graece tum Latine). Far from diminishing the philosophical value of his deliberation,32 this constitutes a further foreshadowing of the philosophical treatises of the 40s, in many of which Cicero will present opposing philosophical arguments in a consciously rhetorical manner, through the use of different speakers and a dialogue form.33 It is tempting to speculate about what use Cicero made of the two languages on this occasion. Did he alternate from question to question? Did he choose a language for each side, and if so, was he consistent? We cannot know what his practice actually was, but the occasion is significant, for we find Cicero, in a time of serious personal and political crisis, expressing Greek philosophical ideas in Latin.

This letter represents, moreover, a further development in Cicero’s use of the deliberative mode in utramque partem. In the first instance, in the letter from 60 discussed above, we saw Cicero alluding to the method of deliberating  but not actually applying the paradigm rigorously. An intermediate stage, also dealing with the issue of deciding on the appropriate course given the conflict between Pompey and Caesar, can be seen in a letter to Atticus written in mid-February of 49, asking for advice:

but not actually applying the paradigm rigorously. An intermediate stage, also dealing with the issue of deciding on the appropriate course given the conflict between Pompey and Caesar, can be seen in a letter to Atticus written in mid-February of 49, asking for advice:

maximis et miserrimis rebus perturbatus, cum coram tecum mihi potestas deliberandi non esset, uti tamen tuo consilio volui. deliberatio autem omnis haec est, si Pompeius Italia excedat, quod eum facturum esse suspicor, quid mihi agendum putes. et quo facilius consilium dare possis, quid in utramque partem mihi in mentem veniat explicabo brevi. (Att. 8.3.1; SB 153)

Disturbed by my truly terrible situation, although I have no ability of deliberating with you face to face, nonetheless I wanted to make use of your counsel. But the entire deliberation lies in the following question: if Pompey leaves Italy, which I suspect he will, what do you think I must do? And in order to allow you better to give your advice, I will briefly lay out what comes into mind in favor of each course of action.

In this case, Cicero proceeds in the way he formally outlines in the beginning, summarizing in turn the arguments in favor of each choice, discussing the likely consequences of either decision should Pompey or Caesar emerge victorious in the end,34 and coming back again and again to the limitation imposed on his freedom of action by the fact that he is still in possession of the fasces in expectation of his Cilician triumph.35 The form that his presentation takes is a combination of the particular and the general. For the most part, specifics of his situations are referred to and the main players are mentioned by name. He also frames his case in the traditional way, by invoking exempla from the Roman past:36 he appeals to the precedent of Lucius Philippus, Lucius Flaccus and Quintus Mucius, who remained in Rome under Cinna’s dominatio.37 He singles out Mucius as the one who articulated his desire to sacrifice himself rather than bear arms against his country. A counterexample is provided not by a Roman, but by a Greek: Thrasybulus, who was exiled by the Thirty Tyrants but then defeated the Thirty and their Spartan supporters, eventually restoring democratic government to Athens.38 Cicero is using the exempla, whose range he expands to include Greek figures, to think about the analogous decision that he must make, either to leave his fatherland to join the party whose goals are closest to his own or to reject the horrible option of taking up arms against Rome.39 Yet within this discussion a more generalized type of deliberation also takes place, which anticipates the fully generalized questions of Att. 9.4 (SB 173): Cicero switches from considering his obligation to Pompey as an amicus to thinking about what is expected of a man like him, a vir fortis et bonus civis.40 In a similar move, in another letter to Atticus written a week and a half later Cicero quotes Scipio’s description (in book five of his De Re Publica) of the ideal statesman, moderator rei publicae, measures Pompey against that standard, and finds him lacking.41 We can then see 9.4 as a culmination of Cicero’s gradual integration of a philosophical mode of deliberation into his practical thinking. First alluded to and carrying some weight by virtue of its association with the philosophical way of thinking, then applied more formally as a framework when he asks the philosophically-minded Atticus for advice, until finally, penetrating into the body of the discussion itself through a more generalized look at his situation, the philosophical model emerges as in itself sufficient to guide his actions without any need to deal directly with specifics. The philosophical model seems to prove more appealing as the particulars of the situation become increasingly uncertain and difficult to control.

Along these same lines, there are moments when Cicero’s despair at his inability to come to the right decision using rational means leads him to outbursts of frustration because intellectual resources seem to be failing him. A letter of mid-March 49, written shortly after Pompey left Italy, Att. 9.10, shows him angry at his decision not to follow Pompey (amens) and so overcome by longing that he is led to compare his relationship with Pompey to a love-affair (sicut  nunc emergit amor, nunc desiderium ferre non possum, nunc mihi nihil libri, nihil litterae, nihil doctrina prodest, “now my love bursts forth, now I can not endure the longing, now books, letters, learning are of no use to me” (Att. 9.10.2; SB 177).

nunc emergit amor, nunc desiderium ferre non possum, nunc mihi nihil libri, nihil litterae, nihil doctrina prodest, “now my love bursts forth, now I can not endure the longing, now books, letters, learning are of no use to me” (Att. 9.10.2; SB 177).

A bitterly ironic reference to exactly the kind of philosophical deliberation that Cicero once employed in making his decision and later found insufficient comes in a letter addressed to Paetus, written at a very different time, late in the year 46, when the political situation following Caesar’s departure for Spain seemed stable and, thus, to Cicero, hopeless (nor is he very proud of his own conduct during this time):42

miraris tam exhilaratam esse servitutem nostram? quid ergo faciam? te consulo, qui philosophum audis. angar, excruciem me? quid assequar? deinde quem ad finem? (Fam. 9.26.1; SB 197)

You wonder that our slavery is so cheery? What am I to do then? I ask you for advice; you are the one who listens to a philosopher. Should I suffer? Should I torment myself? What would I accomplish? Then to what end?

The normative tone of the Latin deliberatives here is reminiscent of the verbal adjectives of Att. 9.4.2 (SB 173), discussed above. In that earlier letter the phrasing of the questions suggested the author’s inclination towards the imperative of virtue dictated by Greek philosophy. Here he implies negative answers and emphasizes the self-destructiveness and futility of trying, in his present circumstances, to come to terms with the philosophically motivated course of action. He pushes against Paetus’ imagined disapproval by directing him to the content of the lectures he is probably attending in Naples: Cicero is enjoying himself, so Paetus the Epicurean should be pleased. Instead, the imaginary Paetus exhorts Cicero to live in litteris. This occasions a new burst of frustration with intellectual life as having a modus: one has to do something else, so Cicero is dining with friends. The tone of this letter is in sharp contrast to that of the treatises, especially to the prefaces in which Cicero consistently emphasizes philosophy’s potential to be useful in all eventualities and the imperative to follow its precepts regardless of circumstances. At this later stage the philosophically based action has been displaced from Cicero’s life, where due to his helpless circumstances it is of little use, into his writing. Unable to practice virtue in the way philosophy dictates, he can at least teach virtue in the hopes of inspiring his readers to know and follow what is proper better than he can himself.43

I conclude this section by looking at another intriguing piece of evidence, provided by Ad Atticum 16.5 (SB 410), a letter that will move our focus from deliberative modes to the role of philosophy in the formation and improvement of character. This letter describes the character transformation undergone by Quintus the Younger, the wayward nephew of both Cicero and Atticus. The description is a deliberate fake, as we know from an earlier letter that Cicero sent to Atticus by special courier and which is fortunately preserved as well, Ad Atticum 16.1 (SB 409). This letter indicates that Quintus, who was staying with Cicero and visited Brutus with him, was putting pressure on his uncle to use him as a courier and send a letter to Atticus, to whose house he was traveling next. The young man’s excessive eagerness aroused Cicero’s suspicions that the letter would not reach Atticus unread; thus, he penned the false praise of Ad Atticum 16.5.44 Shackleton Bailey’s comment on Ad Atticum 16.5.2 expresses surprise that Cicero would expect someone of Quintus’ intelligence to be taken in by the letter given the “stilted style of this paragraph.” Yet Quintus’ father had accepted his transformation as genuine, and Cicero’s decision to send a letter to warn Atticus indicates that he expected that Atticus himself might be taken in. Thus, though we may feel that, had the letter been genuinely meant, Cicero would have demonstrated a shocking level of credulity, it must nevertheless be acknowledged in its general lines to have been sufficiently in character and reflective of his thought to appear plausible to Atticus and to the expected over-reader, Quintus himself.

Before I discuss the content of the letter, some background is in order. Quintus the Younger occupies a special place in the correspondence between Cicero and Atticus, because the two men have the same blood relationship to him and in particular because he is the offspring of a marriage that they arranged and repeatedly patched up. Unlike the letters about Quintus the Elder and Pomponia, the young man’s parents, in which each correspondent predictably takes a defensive stance on behalf of his sibling, Cicero’s references to the younger Quintus show his expectation that he and Atticus are in full agreement about the young man. The relationship between Quintus and his two uncles goes through a number of stages. He first appears in letters from Cilicia, traveling to and within the province in the company of his younger cousin, Marcus. Cicero the unwilling governor is making the best of his year of exile, as he perceives it, by at least providing an educational opportunity for his son and nephew. The two boys are often treated identically, though there are indications that Quintus is in need of some guidance. Cicero’s paternal attitude towards Quintus at this point can be taken for granted.45

A letter of April 49, however, makes a reference to Quintus’ problematic character as a familiar topic of discussion (nosti reliqua) between the two men.46 It is clear that Quintus is now seen as a potential source of danger to Cicero, but that the latter is still trying to take him in hand. The danger became realized when Quintus, having followed Pompey to Greece with his father and having been pardoned by Caesar following Pompey’s defeat, took it upon himself to slander his uncle Cicero in the Caesarian circles given the slightest opportunity. Even before he was received by Caesar, young Quintus presented himself as Cicero’s professed enemy (se mihi esse inimicissimum) and prepared to accuse his uncle in Caesar’s presence.47 As late as August of 45, he is still found portraying his uncle (and, now, his father as well) as dangerous enemies of Caesar and his regime (Att. 13.37.2; SB 346). So it was that in the years immediately before and after the civil war, Quintus the Younger proved first a painful disappointment, then a source of embarrassment, and at last a potential danger to his uncles.48

The situation remained unchanged in the months directly following Caesar’s assassination. Quintus expressed his loyalty to the dictator’s memory in an ostentatious manner that upset and worried his relatives, and then he found a place for himself at Antony’s side.49 The surprising change in Quintus’ attitude and behavior is first mentioned in the letter of June 44, and his reported protestations of dislike for Antony’s regime are initially met with suspicion both by Cicero and Quintus the Elder. However, the latter, to his brother’s dismay, is quickly won over by expressions of filial duty and affection.50 On July 3rd Quintus appeared at his uncle’s house and a couple of days later accompanied him to Puteoli to reconcile with Brutus.51 It is against this background that the letter praising Quintus needs to be read. I will quote the relevant section in its entirety:

nunc audi quod pluris est quam omnia. Quintus filius52 fuit mecum dies compluris et, si ego cuperem, ille vel pluris fuisset; sed quam diu fuit, incredibile est quam me in omni genere delectarit in eoque maxime in quo minime satis faciebat. sic enim commutatus est totus et scriptis meis quibusdam quae in manibus habebam et adsiduitate orationis et praeceptis ut tali animo in rem publicam quali nos volumus futurus sit. hoc cum mihi non modo confirmasset sed etiam persuasisset, egit mecum accurate multis verbis tibi ut sponderem se dignum et te et nobis futurum; neque se postulare ut statim crederes sed, cum ipse perspexisses, tum ut se amares. quod nisi fidem mihi fecisset iudicassemque hoc quod dico firmum fore, non fecissem id quod dicturus sum. duxi enim mecum adulescentem ad Brutum. sic ei probatum est quod ad te scribo ut ipse crediderit, me sponsorem accipere noluerit eumque laudans amicissime mentionem tui fecerit, complexus osculatusque dimiserit. quam ob rem etsi magis est quod gratuler tibi quam quod te rogem, tamen etiam rogo ut, si quae minus antea propter infirmitatem aetatis constanter ab eo fieri videbantur, ea iudices illum abiecisse mihique credas multum adlaturam vel plurimum potius ad illius iudicium confirmandum auctoritatem tuam. (Att. 16.5.2: SB 410)

Now hear what is worth more than all else. Quintus was with me for a number of days, and, if I wanted, would have stayed even longer; but as long as he was here, it is amazing how he pleased me in everything and especially in that respect in which he used to be the least satisfactory. For he is so entirely transformed both by certain writings of mine which I happened to have with me, and by my uninterrupted discourse and teachings that he will have such disposition towards the republic as we desire him to have. After he had not only assured me of this, but also convinced me, he pleaded with me insistently in many words to assure you that he would be worthy of both you and me; and he was not asking that you believe (in his changed attitude) straightaway, but, that once you yourself observed it, you treat him with affection. And unless he had convinced me of this and I had judged that the transformation I am describing would remain firm, I wouldn’t have done what I am about to narrate. For I took the young man with me to Brutus. And he (Brutus) was so persuaded of what I’ve been telling you that he in his own right trusted (Quintus), wasn’t willing to accept me as a guarantor, and, in praising him, made a most friendly mention of you, then, having embraced and kissed him, let him go. For this reason, although there is more to congratulate you on than to ask you for, nonetheless I do ask you that, if any of his previous actions, on account of the weakness of his age, seemed to be rather inconstant, you judge that he has cast them off and believe me that the weight of your opinion will add much, or, rather, the most significant, influence towards confirming his new judgment.

Cicero’s goal, as we know, is to write a letter that will convince the snooping Quintus that his uncle was thoroughly taken in by his professions of change. What is significant for my purposes are the types and the hierarchy of reasons Cicero advances to justify this apparent change to Atticus. Even though both Cicero and Atticus, as Quintus must have been aware, were already informed of his intention to change sides, Cicero represents the change as having largely occurred under his roof and through his personal influence. This in itself would not seem suspicious to Quintus or Atticus, as this is not a simple exaggeration, but rather a convention common to the genre of litterae commendaticae, which locates the request made of the addressee entirely within the relationships between the writer and the addressee, on the one hand, and the writer and the man recommended in the letter, on the other.53

Within the functioning of this generic convention, the author of a letter would normally place emphasis on the particular aspects of the relationships involved that he expected would appeal to his correspondent.54 In this case, however, the existence of a specific expected over-reader, who was in fact the more important addressee, rather complicates the situation. Cicero writes what he expects will appear plausible to Quintus. That, in turn, is his perception of what Quintus sees as important to Cicero in his relationship with Atticus. The influences Cicero specifies as having affected change in Quintus are his own writings, scriptis meis, his conversation, adsiduitate orationis, and his teachings, praecepta. The arrangement of the three elements in a descending tricolon puts the most weight on the first element. Thus, the oratio and the praecepta in question must be related to, and follow from, the content of whatever work(s) Cicero gave Quintus to read. These are likely to be texts that he was working on at the time: the two possibilities that are cited by Shackleton Bailey are the lost De Gloria and De Officiis. De Officiis is a particularly tempting suggestion because of its prescriptive ethical content and explicit didactic intent: after all, the work is dedicated to Quintus’ cousin, Cicero’s son Marcus.55

While the account of how Cicero influenced Quintus through these means is insincere, the fact of Quintus’ expected over-reading assures the accuracy of the description of the interaction that took place between uncle and nephew. Cicero must in fact have given Quintus some of his writings to read and then discussed their implications for Quintus’ own behavior. That means that Cicero felt that his works did have potential for use as a pedagogical and deliberative tool.56 He viewed the younger Quintus as a man without ethical potential and did not believe that philosophy alone could reform his character, but nonetheless offered his writings to Quintus with the avowed goal of improving his character. This lends credence to Cicero’s hope, expressed in the prefaces to the treatises, that his work of making philosophy available and sufficiently Roman might affect a change in the younger generation of the elite. For, after all, he felt that philosophy was able to influence him in no small matter, his regard for his own reputation:

de fama nihil sane laboro; etsi scripseram ad te tunc stulte ‘nihil melius’; curandum enim non est. atque hoc ‘in omni vita sua quemque a recta conscientia traversum unguem non oportet discedere’ viden quam  an tu nos frustra existimas haec in manibus habere? (Att. 13.20.4; SB 328)

an tu nos frustra existimas haec in manibus habere? (Att. 13.20.4; SB 328)

I certainly don’t worry at all about my reputation; although I had written to you stupidly back then that “nothing is better”; for one must not concern oneself with it. And this, “no one should depart from his upright conscience even a nail’s breadth in all of his life,” do you see how philosophically it is expressed? You don’t think that I’ve been busying myself with these things in vain, do you?

PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS

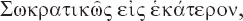

A number of letters touch on Cicero’s views of the relationship between philosophy, as a discipline and a practice, and political life. This is an issue of central importance for contextualizing the claims that Cicero makes in the prefaces to the philosophica about philosophy’s potential as an alternative to traditional public life under circumstances of forced political inactivity. Specifically, the notion that there is a complementary and mutually dependent relationship between traditional political activity and intellectual activity broadly defined (studia), and philosophy in particular, is in evidence in Cicero’s earliest surviving correspondence with Atticus. This early appearance of the pattern whereby disappointment or restriction in the political arena leads to a greater investment in intellectual life could be seen as corresponding to the traditional otium/negotium paradigm, though it exhibits significant differences from the Ciceronian take on that model as presented in a more public context, the Pro Archia being the best example. That speech argued for greater recognition of the importance of intellectual engagement—in this case with poetry in particular—but nonetheless assigned it a decidedly secondary position. It was a way for the statesman to recharge so that he could return to his traditional negotia refreshed and better able to fulfill his duty to the state.57 What we see in the letters differs in that the two types of activity are posited as choices, so that a statesman who is unable to perform his functions as desired can imagine redirecting his energies into intellectual life.

In the summer of 61, in the aftermath of Clodius’ trial and in anticipation of the consular elections on July twenty seventh, Cicero’s position was somewhat precarious, and he felt this state of affairs particularly acutely, coming as it did so soon after his triumphant consulship. At the end of a long letter addressed to Atticus in early July, he discussed, among other things, the lex de ambitu proposed by Lurco, one of the tribunes.58 The bill stipulated that those who promised bribes in a tribe would only be punished if money actually changed hands. Cicero found the proposal absurd. At the end of the discussion of the matter, his indignation seems to overflow, his irritation with the bill compounded by frustration at Pompey’s promotion of Afranius’ candidacy for the consulship, a travesty in Cicero’s view:

sed heus tu, videsne consulatum illum nostrum, quem Curio antea  vocabat, si hic factus erit, fabam mimum futurum? qua re, ut opinor,

vocabat, si hic factus erit, fabam mimum futurum? qua re, ut opinor,  id quod tu facis, et istos consulatus non flocci facteon. (Att. 1.16.13; SB 16)

id quod tu facis, et istos consulatus non flocci facteon. (Att. 1.16.13; SB 16)

But, alas, do you see that that consulship of ours, which Curio used to refer to as apotheosis, if he [Afranius] is elected, will become a matter for vulgar ridicule? So, I think, one must engage in philosophy, what you are doing, and reckon those consulships of theirs of no import.

At this point Cicero leaves off his discussion of public affairs, finally fed up, and turns to personal matters, including poetry. In this context Cicero mentions epigrammata that Atticus composed for the shrine of Amalthea that he built on his Buthrotum estate:59 epigrammatis tuis, quae in Amaltheo posuisti, contenti erimus, praesertim cum et Thyillus nos reliquerit et Archias nihil de me scripserit, “we’ll have to content ourselves with the epigrams you have placed in your Amaltheum, especially since Thyillus has abandoned us and Archias has written nothing about me” (Att. 1.16.15; SB 16). These poems have been connected to a passage in Nepos’ Life of Atticus that describes, among Atticus’ literary compositions, books containing brief verse descriptions of the accomplishments of great Romans that were placed under their imagines.60 Given the rest of the sentence, the epigrammata Cicero is referring to have him as their subject, as they are to provide him some partial consolation for the neglect he has suffered from other poets whom he had expected to celebrate his achievements.61 The tone, and the mention of Archias, a year after the latter’s trial, seems to bring us back to the model set out in Cicero’s speech on that occasion: Cicero is turning now to Atticus’ celebration of him both as a temporary escape from the frustrations of the political life and to find inspiration in a literary representation of his greatness. This discussion of poetry, following as it does the mention of turning to philosophy as practiced by Atticus, lies behind Shackleton Bailey’s interpretation of  as meaning “literary studies” and his accompanying comment that “how far philosophia corresponds to ‘philosophy’ depends on the context.”62

as meaning “literary studies” and his accompanying comment that “how far philosophia corresponds to ‘philosophy’ depends on the context.”62

I suggest, however, that the discussion of poetry does not illustrate what Cicero was proposing, if only at a moment of intense frustration, in the earlier passage, but rather represents a retreat from it and a return to the more traditional paradigm. The earlier appeal to Atticus as exemplifying what Cicero is invoking, namely, the downgrading of the highest magistracy on the scale of priorities, indicates that Cicero is not referring to any individual activities that Atticus engages in, but rather to his decision not to pursue a senatorial career.  then represents more than literary pursuits, more than philosophical practice even; it connotes intellectual activity as a replacement for active political life. The hybrid facteon, a Greek formation given to a Latin verb,63 is then itself a playful illustration of where the model here proposed could lead: a life of action, still Roman at its foundations, but conceived of in a Greek manner. It is a glimpse of an alternate path. But no more than that.

then represents more than literary pursuits, more than philosophical practice even; it connotes intellectual activity as a replacement for active political life. The hybrid facteon, a Greek formation given to a Latin verb,63 is then itself a playful illustration of where the model here proposed could lead: a life of action, still Roman at its foundations, but conceived of in a Greek manner. It is a glimpse of an alternate path. But no more than that.

What makes this brief gesture significant is the frequent recurrence of such momentary flirtations with an alternative in times of political difficulties. The alternative is often philosophically based, though sometimes more broadly conceived as studia or litterae. It continues to crop up during the period leading up to Cicero’s exile. In Ad Atticum 2.5.2 (SB 25), written in April 59 when Cicero is navigating a difficult course vis-à-vis the triumvirs, he hints at a temptation, the possibility of the augurate, only immediately to correct himself:

vide levitatem meam! sed quid ego haec, quae cupio deponere et toto animo atque omni cura  sic, inquam, in animo est; vellem ab initio, nunc vero, quoniam quae putavi esse praeclara expertus sum quam essent inania, cum omnibus Musis rationem habere cogito. (Att. 2.5.2; SB 25)

sic, inquam, in animo est; vellem ab initio, nunc vero, quoniam quae putavi esse praeclara expertus sum quam essent inania, cum omnibus Musis rationem habere cogito. (Att. 2.5.2; SB 25)

Look at my fickleness! Why should I bother with these things, which I want to set aside and to devote all my spirit and all my efforts to philosophy? That, I say, is what is in my heart. If only those had been my wishes from the beginning; but now, since I have learned from experience how empty are the things that I considered most glorious, I intend to deal with all the Muses.

Here, as in the previous letter, disappointment with the options currently available to him in the political arena and with the general state of affairs is what leads Cicero to invoke the intellectual alternative. Once again, it is not a thoroughly worked-out program for replacing his current commitments, but rather a general reference to the intellectual sphere as the natural place to turn to for a substitute. Nor is it entirely serious, as Cicero’s self-conscious comment on the temptation that a prestigious priesthood poses despite his alleged commitment to intellectual remove clearly indicates. Yet such offhand comments continue to turn up. Frustrated with the triumvirs again, Cicero urges Atticus: qua re, mihi crede,  iuratus tibi possum dicere nihil esse tanti, “therefore, trust me, let’s give ourselves to philosophy. I can swear to you that nothing is more valuable” (Att. 2.13.2; SB 33).

iuratus tibi possum dicere nihil esse tanti, “therefore, trust me, let’s give ourselves to philosophy. I can swear to you that nothing is more valuable” (Att. 2.13.2; SB 33).

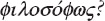

More firmly rooted is the reference in a letter of late April–early May of 59, written in Formiae in response to Atticus’ reaction to the newly proposed agrarian bill. The letter shares with the others in this group an overall sense of disappointment and frustration. The desire to turn away from politics is here expressed entirely within a philosophical framework:

nunc prorsus hoc statui ut, quoniam tanta controversia64 est Dicaearcho, familiari tuo, cum Theophrasto, amico meo, ut ille tuus

longe omnibus anteponat, hic autem

longe omnibus anteponat, hic autem  utrique a me mos gestus esse videatur. puto enim me Dicaearcho adfatim satis fecisse; respicio nunc ad hanc familiam quae mihi non modo ut requiescam permittit sed reprehendit quia non semper quierim. qua re incumbamus, o noster Tite, ad illa praeclara studia et eo unde discedere non oportuit aliquando revertamur. (Att. 2.16.3; SB 36)

utrique a me mos gestus esse videatur. puto enim me Dicaearcho adfatim satis fecisse; respicio nunc ad hanc familiam quae mihi non modo ut requiescam permittit sed reprehendit quia non semper quierim. qua re incumbamus, o noster Tite, ad illa praeclara studia et eo unde discedere non oportuit aliquando revertamur. (Att. 2.16.3; SB 36)

Now I have indeed decided, since there is such a great dispute between your intimate Dicaearchus and my friend Theophrastus, as your man puts the practical life ahead of all others by far, but mine prefers the contemplative, that I appear to have gratified each of them. For I think I have certainly done more than enough for Dicaearchus; now I look back to that camp that not only allows me to take some rest, but scolds me for not having always been at peace. Therefore, let us, my dear Titus, direct our attention to those splendid studies and finally return to that place which I should never have left.

The general sentiment expressed in this letter is largely the same as in those discussed above: political life has produced only disappointments, so it is time to set politics aside and return to the more potentially satisfying intellectual pursuits. What is different in this formulation, however, is that both alternatives are here framed, for the first time, as philosophically based choices. Cicero is no longer conceiving of his options as political versus the intellectual, but as a decision between two philosophical approaches, a choice motivated primarily not by practical, but by philosophical considerations.65 As in the deliberative letters discussed in the previous section, Cicero’s correspondence here shows episodic, but deepening forays into the philosophical sphere.

What then about the more traditional way of conceiving of studia and intellectual activity—as located securely in the realm of otium, as meant to provide relaxation and diversion from the daily political labors—the view that, despite all the efforts to elevate their status, lies at the foundation of Cicero’s defense of Archias? It too crops up in a letter of this period (and it would be surprising if it did not). In asking Atticus to oversee the transfer of a library into his possession and professing his great desire for the books, Cicero identifies his studia as a refuge to which he devotes all the time he can spare from the toil of the courts (Att. 1.20.7; SB 20).66 In April 55, a similar sentiment arises in regard to the library of Faustus Sulla, as Cicero is anticipating his meeting with Pompey:

ego hic pascor bibliotheca Fausti. fortasse tu putabas his rebus Puteolanis et Lucrinensibus. ne ista quidem desunt, sed mehercule ut a ceteris oblectationibus deseror et voluptatibus cum propter aetatem tum67 propter rem publicam, sic litteris sustentor et recreor maloque in illa tua sedecula quam habes sub imagine Aristotelis sedere quam in istorum sella curuli tecumque apud te ambulare quam cum eo quocum video esse ambulandum. sed de illa ambulatione fors viderit aut si qui est qui curet deus. (Att. 4.10.1; SB 84)

Here I feast on Faustus’ library. Perhaps you thought it was all that Puteolan and Lucrine stuff. Certainly, that is not lacking either. But as surely as all others delights and pleasures fail me, given both my age and the state of the republic, so I am sustained and reborn through letters and prefer to sit in that little seat that you have under the likeness of Aristotle than in those men’s curule seat, and to walk with you at your house than with him, with whom I see that I must walk. But about that walk may fortune take care and if there is some divinity that concerns itself with it.

The library in this passage plays the same restorative role as the literary studia in Att. 1.20 and the Pro Archia.68 Yet the sentiment here has a lot in common with the group of letters discussed above, in which intellectual engagement is conceived of as a potential alternative to the political life. Atticus and Aristotle, representing the philosophical life, are imagined as a possible alternative to Pompey and the sella curulis, the now corrupt political life.69 Cicero both expresses a preference for the contemplative model and allows his sense of duty to hold him to his earlier choice. The two strands in his thought as found in the letters thus coalesce here, and the restorative function of intellectual pursuits emerges as the lesser, albeit more appealing option. It is an attractive refuge at a difficult time when full commitment is not a possible alternative.

I now move to discuss letters addressed to men other than Atticus, all of which come from the 40s and are thus directly relevant to the question of how Cicero presents philosophy in relation to politics during the period leading up to his philosophical treatises. The first letter, written to Cato during Cicero’s term as governor of Cilicia, is part of a publicity campaign designed to induce the senate to vote him a supplication for his military accomplishments in his province as the necessary first step towards a triumph—a measure that Cato was expected to, and, in fact, did, oppose.70 As a letter addressed to someone whose relationship with Cicero was far from intimate, and one written primarily to convince the addressee to do something that is advantageous to the author, this is a type of text whose purposefully rhetorical nature renders it less useful as a window into the author’s own thoughts. Conversely, precisely because of its sharply persuasive focus, it can be taken as a fairly accurate representation of Cicero’s perception of, on the one hand, what Cato’s reservations would be in this matter, and, on the other hand, what kind of arguments would likely appeal to Cato and secure his support.

Most of Cicero’s persuasive strategies are part of a common stock to be found in any letter containing a request. The very fact of his writing a personal letter to Cato that includes a detailed account of the military action honors the addressee, since information about the campaign would be available to Cato in the official dispatch that Cicero sent to the senate. Thus, the importance of the account, which occupies most of the letter, lies not in its content so much as in the fact that Cicero is singling Cato out of the senatorial body as someone who deserves to receive a personalized version.71 The letter also contains the standard appeal to the history of the relationship between the two men:72 Cicero recalls the occasions on which the two were political allies, the times when Cato expressly praised Cicero in public. He cites Cato’s precedent in having voted in favor of a supplication for Cicero in the aftermath of the Catilinarian conspiracy in 63, makes general references to friendship (amicitia), a commonality of pursuits, and an exchange of favors (studiis et officiis mutuis), and alludes to the relationship between the two men’s fathers73 (necessitudine paterna).74 But the part of the letter that stands out is the concluding section, which deals with the philosophical connection between the writer and the addressee:

extremum illud est, ut quasi diffidens rogationi meae philosophiam ad te adlegem, qua nec mihi carior ulla umquam res in vita fuit nec hominum generi maius a deis munus ullum est datum. haec igitur, quae mihi tecum communis est, societas studiorum atque artium nostrarum, quibus a pueritia dediti ac devincti soli prope modum nos philosophiam veram illam et antiquam, quae quibusdam otii esse ac desidiae videtur, in forum atque in rem publicam atque in ipsam aciem paene deduximus, tecum agit de mea laude; cui negari a Catone fas esse non puto. (Fam. 15.4.16; SB 110)

This is my last point: as if unsure in my request, I dispatch philosophy to you, than which no other thing has been dearer to me in life and no greater gift has been bestowed by the gods upon the race of men: therefore, this unity, which you and I share, of pursuits and accomplishments, devoted to and bound by which since boyhood we, virtually alone, have managed to introduce that true and ancient philosophy, which to certain men seems to be a mark of leisure and sloth, into the forum and into public life and almost into the very battle-line, this unity then pleads with you concerning my glory, and I think that it would not be right for Cato to say “no” to it.

This passage articulates a number of ideas that will find expression in many of the prefaces to the philosophical treatises in the following years. The praise of philosophy as the greatest gift to mankind, the emphasis on its continuous importance in Cicero’s life, as well as the reference to philosophical pursuits as shared by the author and the given dedicatee, are common themes. In particular, there are striking parallels with the preface to the Paradoxa Stoicorum, written in the spring of 46 in a very different political climate. In that treatise Cato himself is featured prominently as both an exemplum and as the uncle of the dedicatee, Brutus.75 Here, in a private letter, it is instructive to find that Cicero not only refers to general views that he would later propagate in the treatises, but also articulates the idea of introducing philosophy into political life. Finding it expressed at a time when the republic, though troubled, seemed fairly stable to the two correspondents lends a certain amount of credibility to its expression at a later time when virtually no other options were available to Cicero. What we see here is Cicero’s representation of what he perceives Cato’s thoughts to be on the desired relationship between philosophy and politics. That Cicero took Cato’s views seriously is indicated by another part of the letter that deals with his conduct as a governor: we know from letters to Atticus that Cicero did in fact try to uphold “Catonian” standards of gubernatorial behavior.76 Thus, it is tempting, in light of this letter, to interpret the composition of the treatises, at a time when Cicero threw himself headlong into a posthumous campaign to glorify Cato, not only as an attempt to bring into existence a new generation that would embrace Cicero’s own views, but a generation of potential Catos, who would admit philosophy into every area of political life, just as he had done.77

Another letter makes reference to the problematic relationship between philosophy and politics, posited by proponents of both. It is addressed to Varro and was written in June of year 46 in expectation of Caesar’s return to Italy. Cicero praises at length Varro’s current life of dedication to scholarship and then goes on to introduce the dichotomy between such a life, conceived by him as in large measure philosophical, and the usual political lifestyle:

quis enim hoc non dederit nobis, ut, cum opera nostra patria sive non possit uti sive nolit, ad eam vitam revertamur quam multi docti homines, fortasse non recte sed tamen multi, etiam rei publicae praeponendam putaverunt? quae igitur studia magnorum hominum sententia vacationem habent quandam publici muneris, iis concedente re publica cur non abutamur? (Fam. 9.6.5; SB 181)

For who would not grant us the following, that, at a time when the state either cannot or is not willing to make use of our services, we return to that life which many learned men, perhaps not correctly, but many of them, nonetheless, thought was to be preferred to public life? Therefore since these pursuits in the opinion of great men contain an exemption from public work, why are we not to spend our time in them, when the state allows it?

What is noteworthy and typical here is Cicero’s inability, even at a time when it would seem most natural and when he is addressing a most sympathetic audience, to wholeheartedly follow the line of thought that champions philosophy, and intellectual pursuits more generally, to the exclusion of engagement in politics. He is so deeply uncomfortable with advocating such a view that he qualifies his endorsement, such as it is, not once, but twice. First with the aside, fortasse non recte, which in effect cancels everything he has said in defense of the scholarly life or, rather, transforms his stance vis-à-vis the ideas he is presenting from that of an endorser to that of a reporter carefully keeping his distance. The second qualification further undermines his support for this view: Cicero suggests that his and Varro’s turn to the contemplative life is acceptable only because they have the permission of the public; it is the state that has let them go, concedente re publica. Finally, in addition to these fairly explicit qualifying statements, Cicero’s insistence on citing the authority of “great men” as the real source of the opinion, and, in particular, his repetition of multi, as if saying “at least there is strength in numbers on this side,” also serve to mark his discomfort.

This formulation reveals Cicero’s ultimate unwillingness to take sides in the controversy. Just as he tried to incorporate philosophy as much as possible into his practice as an active statesman, and gestured towards a whole-hearted acceptance of the contemplative life in times of political difficulties, so in the post-civil war period, when he is debarred from politics, he is yet unable to resign himself to “pure” philosophy. The political ends up permeating everything he does. Thus, the production of the treatises performs a function in his later life that mirrors such diverse episodes in his earlier career as inserting philosophical views in his speeches and conducting his governorship on an ethically correct basis. It reflects his desire to reject the divisive view and bring the two spheres, politics and philosophy, together in a harmonious whole, an enterprise in its nature quite parallel to the other major aspect of the treatises, the bringing together of the Greek and the Roman, theory and exempla.

As far as the letters allow us to supplement what we know based on Cicero’s literary output, then, a rough chronological trajectory of his developing views can be mapped out. We can see occasional recourse to intellectual pursuits in their restorative capacity, combined with gestures towards the possibility of choosing the intellectual over the political in times of crisis in the pre-civil war years, evolving into a comprehensive engagement with philosophy manifested in the process of writing philosophical treatises during the period when he is unable to actively serve the state. This engagement is accompanied, however, by private doubts as to the ultimate validity of the claims he advances for philosophy’s power in his own treatises. The private comments found in Cicero’s letters are as important as the publicly presented ideas of the Pro Archia and the self-justificatory claims in the philosophical prefaces to our understanding of the sources from which the fully developed model of philosophical activity as a substitute for political life will later arise. It is also symptomatic that his reaching out to the intellectual world as a true substitute occurs mainly at times of political insecurity, when Cicero’s political stature and his future prospects are in doubt. Such moments of insecurity could be said to culminate and morph into a permanent state at the time of Caesar’s dictatorship, when we see Cicero reacting by developing a fully worked out model of the intellectual life as a substitute for political engagement.

A question then arises about the place Cicero assigned to intellectual life during his other prolonged period of forced political inactivity, his exile from Rome in the early 50s. In light of later developments, it is striking that the kind of rhetoric about intellectual activity taking the place of politics that we find periodically in the letters, both before and after his exile, and that comes so prominently to the fore in the production of the mid-40s, is entirely absent from the exile correspondence. Why is that? What is the difference between the two periods of exclusion that allows philosophy to emerge for Cicero as an alternative to politics under Caesar but not during exile? The most salient and relevant differences would seem to be the following. First, in the case of exile, it is Cicero alone who is excluded, and not only from the political process, but also from other more basic rights of citizenship. In the 40s, by contrast, Cicero is living through an exclusion that is shared with others; he is part of a class, in fact more than just part: as one of the eldest consulars to survive the civil war, he is seen by some as the leader of this group. Second, while Cicero and others may have had much to complain about the state of the res publica in the early 50s, they saw the basic functioning of the state as still unchallenged. Under Caesar fundamental changes to the institutions of the state, embodied most dramatically in, but not limited to, the role of the dictator, resulted in a political landscape very different from the republican model. What then, does the fact that Cicero turns to philosophy under Caesar, but not during exile tell us about the nature of his project?

One important conclusion is that for him philosophy is not ultimately a matter of private otium, a pastime that can provide solace to an individual. It is, rather, a tool to be used in the public sphere, different in kind, but not necessarily function, from more traditional forms of public service. He does not turn to it as a source of consolation or to create an alternate private world for himself in exile, but engages in philosophical writing only when he, along with an entire class of men who had been devoted to public life, found himself marginalized. Then he presented it as a substitute for a corrupted political process. Cicero’s doubts about the ultimate ability of philosophy to act as a satisfactory substitute do not alter the basic motivations behind his project.

WRITING AS A PRIMARY OCCUPATION