Milan’s cathedral, known as the Duomo, is the city symbol. Begun in 1386, it has been in continual evolution ever since. Indeed, ‘As long as the building of the Duomo’ is a typical Milanese expression. Much like the Duomo, Milan is a work in progress, building with more panache than anywhere else in Italy, for good or ill.

Milan is currently doubling the reach of its metro system, creating new expressways and upgrading its railways. New galleries continue to open, such as the impressive Museum of Cultures (MUDEC) and the Armani/Silos, both of which were inaugurated in 2015. Dilapidated industrial areas are being transformed, and Futuristic districts created, such as ‘Fashion City’, near Garibaldi station, and the ‘City Life’ centre on the site of the old trade fair. The Expo 2015 relaunched Milan as a model of urban renewal, but elsewhere historical districts, such as the bohemian Navigli canal quarter, have also been given a facelift, along with the adjoining Zona Tortona design district.

The lofty Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

Fotolia

Yet ‘old Milan’ survives, whether in the elegant area around the Cathedral, and its enveloping galleries, or in the romantic Brera district, where bohemian bars overlook charming churches. As for the arty Navigli, when sitting in a rustic waterside inn, with the faint rumble of trams beyond, it feels like you’ve been transported from the consumerist Milanese metropolis to timeless provincial Italy. Even the fashion district is home to several intimate art museums that would do Tuscany credit. Throughout the city, cutting-edge restaurants are outnumbered by cosy inns, grande-dame hotels and old-fashioned patisserie shops. The Milanese love tradition as much as they love change.

Getting around

The historic heart of the city is surprisingly compact, with the main arteries fanning out from the great Gothic Duomo and La Scala opera house: northwest to the imposing Castello Sforzesco and Parco Sempione, northeast to the Quadrilatero d’Oro fashion district, north to the arty neighbourhood of the Brera. To the west lies the smart Corso Magenta, with Santa Maria delle Grazie’s The Last Supper by Leonardo, and to the south, the hip Navigli canal quarter. The main attractions of the city can be covered in a few days, usually on foot, but with some short journeys by tram or metro necessary.

The Duomo and Historic Centre

The Duomo (metro Duomo) is the geographical and spiritual heart of the city, so is a natural magnet and the best place to explore first. The historic centre, the centro storico, also provides a representative mix of art museums and Milanese architecture, ranging from the majestic cathedral to La Scala opera house and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, one of Europe’s most elegant shopping galleries. That’s in addition to the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana’s atmospheric art collection and your first contact with Leonardo da Vinci.

Following most of these suggestions makes for cultural overload so try to do as the Milanese do, and be tempted along the way by the distinctive bars and cafés that bring this area to life. Some are mentioned below, but depending on the time of day, there are fuller listings in Restaurants (for more information, click here), Lunch Milanese-style (for more information, click here) and Nightlife (for more information, click here).

Duomo

Dominating the heart of the city, and soaring over the central square, is the Gothic Duomo 1 [map] (cathedral, www.duomomilano.it; daily 8am–7pm; roof, daily 9am–7pm; Duomo Pass provides entry to the cathedral, terrace, museum and the San Gottardo church). The Duomo Info Point is right behind the cathedral at the porch of the Church of Santa Maria Annunciata in Camposanto (tel: 02 7202 3375; Mon–Sat 9.30am–5.30pm, Sun 11am–3pm).

Exploring the roof terraces of the Duomo

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Nothing quite prepares you for the first sight of the monumental facade. This is the third-largest church in Europe, after the cathedral in Seville and St Peter’s in Rome. The area covers 12,000 sq m (130,000 sq ft), the capacity is around 40,000, and the facade is adorned with a forest of 3,000 statues, 135 spires and 96 gargoyles.

Begun in 1386, the Duomo was the brainchild of Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti, whose aim was to create the greatest church in Christendom. The then bishop of Milan, Antonio da Saluzzo, declared a Jubilee to persuade the Milanese to help fund or assist the colossal project. Armourers, drapers, bootmakers and other artisans all lent a hand, while French and German architects, engineers and sculptors, well versed in the Gothic tradition, worked alongside local craftsmen. At one stage, there were around 300 sculptors from all over Europe chiselling away in the cathedral workshops.

The original plan was a building in Lombard terracotta, but Gian Galeazzo changed his mind and decided the entire structure was to be clad in pale but peachy Candoglia marble. This entailed the construction of roads and canals to drag the great blocks of marble from the quarries near Lake Maggiore.

The Madonnina on top of the Duomo

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Madonnina

A much-loved symbol of the city, the Madonnina, atop the Duomo, is 4.46m (14.5ft) high. She was placed on the church’s tallest spire in 1774, and remained the highest point in the city until the Pirelli skyscraper was built in the late 1950s (for more information, click here). The clergy were none too pleased that she had lost her superior position, so a replica was placed on top of the Pirelli Tower.

Despite the huge workforce it was to be more than five centuries before the cathedral was completed. The result is a hybrid of Renaissance, Gothic and Baroque styles, with 19th-century additions. The work on the facade, which dates from the 17th century, gave rise to decades of controversy, and was only finished in 1812 under Napoleon.

Even on a dull day the marble facade looks strikingly bright, almost blindingly so since its recent facelift has left it a lovely peachy-pink colour that changes according to the light. Before entering the church, admire the Gothic apse. Built in 1386–1447, and decorated with sculptures and tracery, this is the oldest part of the Duomo.

While here, traipse up to the Terrazzi (roof terraces) by clambering up the 158 steps, or else take the lift. Apart from sensational views of the city and, on those rare, very clear days, as far as the Matterhorn, you can walk among the forest of spires, statues, turrets and gargoyles and get a closer look at the gilded figure of the Madonnina (Little Madonna), which crowns the cathedral.

Inside the cathedral

From the dazzling white piazza you are plunged into the dimly lit, spartan interior, enlivened by a new, glittering glass bookshop. The five aisles are divided by 52 colossal piers – one for every week of the year – their capitals decorated with 15th-century figures of saints and prophets.

The Duomo has a pillar for every week of the year

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Works of art within the church include sarcophagi, funerary shrines and statues, the most famous of which is the gruesome, anatomical Statue of St Bartholomew Flayed (1562) in the right transept, depicting the saint carrying his own skin. At the end of the transept lies the elaborate marble tomb of Gian Giacomo Medici, by Leone Leoni (1509–90), a pupil of Michelangelo. This was commissioned in 1564 by Pope Pius IV, the brother of Gian Giacomo. Unconnected with the Florentine Medici and nicknamed Il Medeghino (Little Medico), Gian Giacomo was from a Milanese family but was banished from the city after committing a murder. He fled to Lake Como and acquired his wealth from privateering and working as a condottiere (mercenary) in the service of Charles V. A large sum donated to the Duomo, plus family connections, ensured this prominent funerary monument. In the left transept the seven-branched bronze Trivulzio Candelabrum, the work of a medieval goldsmith, is adorned with monsters and mythical figures representing the arts, crafts and virtues.

The church is illuminated by beautiful stained-glass windows, dating from the 15th–20th centuries, which are fully lit up from within at the weekend. The oldest is the fifth window in the right-hand aisle, illustrating scenes from the Life of Christ. The beautiful Gothic windows of the apse are decorated with 19th-century scenes from both the Old and New Testaments. The permanently shining red light in the vault of the Duomo marks the place of a nail said to be from Christ’s cross. On the second Sunday in September, the bishop of Milan is hoisted up to the vault to bring the nail down from its niche for public view.

Stained-glass window in the cathedral

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

A stairway behind the main altar leads down to the Treasury, housing a priceless collection of gold, silverwork and holy vestments. In the neighbouring Crypt (1606), a rock crystal urn contains the body of San Carlo Borromeo (1538–84), clad in full regalia. Archbishop and cardinal of Milan, he was a leading light of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and was canonised in 1610. A staircase near the Duomo entrance leads down to the remains of the 4th-century Baptistery on what was then pavement level. It was here that Sant’Ambrogio is said to have baptised St Augustine.

Piazza del Duomo

The gigantic central piazza, milling with people and pigeons, is awe-inspiring, but lacks the carefree charm of a typical Italian piazza. No cafés spill onto the square, but the historic Camparino is tucked under the porticoes, created by the founder of the Campari dynasty in 1867. It was here, at the entrance to Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, that Verdi used to enjoy a drink after concerts and where, in 1877, Milanese nobility flocked to see the first experiment in electric lighting on the piazza. It was also here, in this Art Nouveau interior, that stressed Milanese still relax over a coffee or Campari, served with over-sized olives. Camparino makes a good start to any evening promenade (for more information, click here).

Piazza del Duomo

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The only landmark on the piazza, apart from the big red Ms of the metro, is Ercole Rosa’s 1896 equestrian statue of Vittorio Emanuele II, first king of Italy, who triumphantly entered Milan in 1859. Despite the piazza seeming uninviting, its monuments are impressive, particularly the new Museo del Novecento.

The remaining campanile of the Church of San Gottardo in Corte

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Palazzo Reale (Royal Palace; www.palazzorealemilano.it; Mon 2.30–7.30pm, Tue–Wed, Fri and Sun 9.30am–7.30pm, Thu–Sat until 10.30pm) on the south side of the Duomo stands on the site of the original Broletto or town hall, destroyed by Frederick Barbarossa in 1162. It was rebuilt in 1171, then later transformed into the Ducal Palace for the Visconti and Sforza dynasties. On the occasion of Galeazzo Visconti’s marriage to Beatrice d’Este in Modena, their entry into Milan was marked by eight days of festivities at the palace. In 1336 the Church of San Gottardo in Corte was built as the Visconti’s private chapel. You can still see the charming colonnaded campanile rising to the rear of the palace, but the church itself was destroyed when the building was incorporated into the neoclassical palace. In 1412 the church steps were the scene of the murder of Giovanni Maria Visconti. As a consequence the family decided to reside in the safer environs of the fortified castle. Under the Sforza a theatre was established at the palace, and in 1595 Mozart, who was only 14, performed here.

The serpent is the symbol of Milan

Fotolia

Milan’s serpentine symbol

A serpent devouring a child is one of the Visconti family symbols (you can spot it on the frescoed ceilings of the Castello Sforzesco, for more information, click here). The derivation of the symbol remains a mystery. It could represent the dragon which, according to legend, terrorised Milan in the early 5th century and was slaughtered by Uberto of Angera, founder of the Visconti, or it could reflect the snake talisman that the Lombards used to wear around their necks.

You can see the symbol all over the city – particularly on the Alfa Romeo logo. When Romano Cattaneo, an Alfa draughtsman, was waiting for a tram in Piazza Castello in 1910, he drew inspiration for the logo of the new Milan-based company from the serpent coat of arms embellishing the castle gateway. On the left side of the Alfa Romeo logo is a red cross on a white background, symbol of Milan.

The current neoclassical aspect of the Palazzo Reale dates from the transformation during the late 18th century, when Empress Maria Theresa of Austria chose Giuseppe Piermarini to remodel the building in neoclassical style, with sumptuously decorated rooms. The palace suffered devastation during the Allied bombardments of 1943, and only recently has been re-opened to its citizens, fully restored, bar an unfinished costume museum. While not one of Milan’s greatest sights, the palace is definitely worth seeing if you are visiting an art exhibition or keen to see the changing styles under the Austrians, the French and the Italian house of Savoy.

Palazzo Reale

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The palace showcases blockbuster art exhibitions (visit www.turismo.milano.it for event information). The rooms are restored in styles that characterise court life in 1781–1860 and can be seen in the Museo della Reggia. The east wing of the Palazzo Reale houses the Grande Museo del Duomo (Cathedral Museum; http://museo.duomomilano.it; Thu–Tue 10am–6pm). The collection charts the history of the Duomo, including a section on how the Madonnina got to the top of the highest spire in 1774, accompanied by displays of the cathedral’s original statuary and stained glass, transferred here for safekeeping.

Part of the Palazzo Reale was demolished in the late 1930s to make way for the three-storey Arengario building, which is now the captivating Museo del Novecento 2 [map] (Museum of the 20th Century; www.museodelnovecento.org; Mon 2.30–7.30pm, Tue–Wed, Fri and Sun 9.30am–7.30pm, Thu and Sat until 10.30pm). The collection ranges from the avant-garde Futurist movement to works from the early 1980s. In pride of place are works by Futurists of the stature of Boccioni and Carra, and Metaphysical artists such as Giorgio di Chirico and Filippo De Pisis. The building, designed in ‘Fascist lite’ style, has been beautifully adapted to its new purpose, and the chic café has already become a popular meeting place.

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

Linking Piazza del Duomo and Piazza della Scala is the pedestrianised Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II 3 [map] (or ‘La Galleria’), a light, airy, glass-and-iron shopping arcade that is one of the most elegant ever created. The cruciform Galleria, built in honour of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, was the work of architect Giuseppe Mengoni, who plunged to his death from the scaffolding on the site months before it was completed in 1878. More cheerfully, this gracious rendezvous, known as il salotto di Milano (Milan’s drawing room), is flanked by a discreet luxury hotel, and by chic cafés, restaurants and designer boutiques, many of which have Belle Epoque facades. Savini is the oldest restaurant, and has been welcoming stars from La Scala since 1867. Prada has been here since 1913, while Louis Vuitton and Gucci are more recent arrivals, with the Gucci café a popular people-watching spot. For somewhere more relaxed, but with lofty views, retreat to the rooftops of La Rinascente around the corner (for more information, click here).

Pavement mosaic in La Galleria

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Take a spin

The colourful pavement mosaics under the glass dome of the Galleria depict the coat of arms of the Savoys and the symbols of four cities: Milan (red cross on a white background), Turin (bull), Florence (lily) and Rome (she-wolf). Tradition has it that spinning your heels on the bull’s well-worn testicles will bring good luck.

Teatro alla Scala

The sombre neoclassical facade of the world-famous opera house gives no hint of the fabulously opulent auditorium. More popularly known as La Scala 4 [map], this is arguably the world’s most celebrated opera house. Few opera houses command such an exacting set of fans, who don’t hesitate to show their disapproval if a singer fails to impress.

La Scala’s two-ton, 900-light chandelier lowered for its annual clean

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Many top names in Italian opera have made their debuts here, among them Puccini, Verdi and Bellini. Commissioned in 1776–8 by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, it was designed by Giuseppe Piermarini and built on the site of a former theatre which was destroyed by fire in 1776. The new theatre was named after the church of Santa Maria alla Scala, which originally stood here. La Scala suffered serious damage during the 1943 air raids, but, symbolically, it became the first city structure to be rebuilt. The reopening was celebrated with a memorable concert conducted by the renowned conductor Toscanini, who returned from America after a 17-year absence.

Provided there are no rehearsals going on, you can peep into the auditorium on a visit to the Museo Teatrale alla Scala (Scala Theatre Museum; www.teatroallascala.org; daily 9am–12.30pm, 1.30–5.30pm). The neoclassical rooms display portraits and busts of famous opera singers and composers, stage designs, musical instruments and operatic memorabilia.

In the centre of Piazza della Scala the bearded figure on the pedestal is Leonardo da Vinci, surrounded by four of his pupils. Facing the Teatro alla Scala, the splendid Palazzo Marino was built for a wealthy Genoese financier, Tommaso Marino, in 1558 and given a new facade in the late 19th century. Today, this is the Town Hall, and you can arrange a guided tour (Mon and Thu, prior booking only). Alternatively, peek through the grill into the Courtyard of Honour from Via Marina, which leads into Piazza San Fedele. Also overlooking the square is the Galleria d’Italia (for more information, click here), but leave it for another day to avoid art overload.

Casa di Alessandro Manzoni

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

In front of the Baroque church of San Fedele stands a statue of Alessandro Manzoni (1785–1873), author of the plodding but renowned I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). This worthy set-text for Italian students is set in Lombardy during the oppressive Spanish rule in the 17th century, and evokes the plague of 1630, which devastated Milan. Born in the city in 1814, Manzoni lived in the nearby Piazza Belgioioso, at the Casa di Alessandro Manzoni (www.casadelmanzoni.it; Tue–Fri 10am–6pm, Sat 2pm–6pm; free) until his death after a fall on the steps of the San Fedele church. The entrance is behind San Fedele in Via Omenoni, named after the eight telamones (figures as pillars) that characterise the Casa degli Omenoni.

Piazza Mercanti

In contrast to the Piazza del Duomo, the neighbouring Piazza Mercanti 5 [map] is an intimate square that was left relatively unscathed by urban development and wartime bombardment. The former political and administrative centre of the city, it is only half its original size, but it preserves the medieval Palazzo della Ragione (1233), a fine porticoed brick building which was formerly the Broletto (law courts). It was built by Oldrado da Tresseno, the podestà (mayor) depicted in an equestrian relief on the piazza side of the palace. Between the second and third arches stands a relief of the half-woolly wild boar (scrofa semilanuta), symbol of the city in ancient times.

Piazza Mercanti

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

On the other side of the square is the lovely Loggia degli Osii, the grey-and-white-striped marble building where banns were declared. The coats of arms displayed on the facade represent the powerful local families of the day. The loggia of the Palazzo della Ragione Fotografia (http://www.palazzodellaragionefotografia.it) used to shelter medieval market stalls; today temporary photographic exhibitions are held here. On the piazza an old well survives, and tables spill on to the square from the charming Al Mercante, a tempting lunch spot from which to admire the remnants of medieval Milan (for more information, click here).

Ambrosiana Gallery and Library

The Pinacoteca Ambrosiana 6 [map] (Ambrosian Gallery; Piazza Pio XI; tel: 02 8069 2215; www.ambrosiana.eu; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm) is an unmissable museum of the Old Masters featuring a Leonardo-filled library. As such, it is both an art collection second only to the Pinacoteca di Brera, and an opportunity to see Leonardo da Vinci drawings in a hushed, atmospheric, deeply Milanese setting. The building is a fine example of late 16th-century Lombard architecture, with mullioned windows, frescoed walls and vaulted ceilings.

Biblioteca Ambrosiana

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

In 1609 Cardinal Federico Borromeo commissioned the Biblioteca Ambrosiana (Ambrosian Library) to house his huge array of manuscripts, prints and books, and private art collection. As a patron of the arts, he donated this outstanding collection to the Ambrosian Foundation in 1618, a collection that has been further enriched over the centuries. The Biblioteca is reputedly the first public library in Italy. Some might say that it’s been downhill ever since as Italians are no longer dedicated readers, and much prefer the visual arts, which carry more prestige. But the Leonardo folios combine both drawings and written observations.

The highlights of the Ambrosian gallery are the first rooms, containing numerous works from Federico’s original private collection. Masterpieces include: Titian’s Adoration of the Magi (Room 1); The Musician (Room 2), depicting a musician in the Sforza Court and attributed to Leonardo da Vinci; Raphael’s cartoon for the School of Athens fresco in the Vatican (Room 5); and Caravaggio’s famous Basket of Fruit (Room 6), of which Federico wrote, ‘I would have liked to have put another similar basket next to it, but as nobody could equal the beauty and incomparable excellence of this one, it remained alone.’ There are also paintings by Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Bergognone, Luino and Bramantino, along with Flemish and Dutch art. The visit ends in the library, with the largest extant collection of Leonardo’s drawings and designs. Known as the Codex Atlanticus, the collection has been in the Ambrosiana since 1637, but can only now be seen properly, with the folios displayed on a rotational basis. The Codex is a window into the mind of a true Renaissance man. On display might be drawings of war devices, flying machines, canal sluice gates, sketches of bombardments, or anatomical and botanical studies.

Santa Maria Presso San Satiro

You could easily miss Santa Maria Presso San Satiro, a gem tucked away south of the Piazza del Duomo (Via Speronari 3; Mon–Fri 7.30–11.30am, 3.30–6.30pm, Sat 3.30–7pm, Sun 10am–noon and 3.30–7pm). Legend has it that a fresco of the Madonna and Child, which decorated the 9th-century chapel of San Satiro, shed blood when it was vandalised in 1242. Bramante later remodelled the chapel and provided a safe haven for the fresco, which you can see on the high altar. The architect ingeniously created the impression of depth by devising a trompe l’oeil apse.

The Cappella della Pietà (off the left transept) has early medieval frescoes and a terracotta Pietà (1482) by Agosto De Fondutis; there are more of his terracottas in the lovely baptistery. Bramante’s plans for the facade never materialised, the present one being 19th-century neo-Renaissance. The beautiful bell tower at the back of the church, seen from Via Falcone, is one of the oldest in Lombardy.

If feeling peckish, consider a light lunch at Ottimo Massimo, Peck, or Eat’s Store, or a leisurely affair in Al Mercante or Boeucc, for an old-school Milanese atmosphere (see Historic Centre restaurants, for more information, click here).

Castello Sforzesco and the Northwest

The monumental Castello Sforzesco (metro Cairoli) was the stronghold and residence of the mighty Milanese dynasties, the Visconti and Sforza. Dating from 1360 and extended over the centuries, it is the city’s largest historical complex, and stands as a symbol of the dramatic events of Milan’s history. The rambling Parco Sempione, stretching from the castle to the Arco della Pace, was formerly a Sforza hunting reserve but has been a park since the late 19th century.

Parco Sempione was landscaped in 1893 in so-called English style, which, in Italy, is often a euphemism for a romantic but slightly unkempt look. The sprawling park is mostly rolling lawns, but also embraces a lake, cycle paths, children’s play areas and an intriguing design museum. The lack of a museum café in the Castello Sforzesco means that it’s best to have lunch in the Triennale design museum (for more information, click here) or to graze just outside the park at Van Bol & Feste, who also provide tasty picnic treats (for more information, click here).

Castello Sforzesco

Castello Sforzesco 7 [map] was originally built in 1360–70 by Galeazzo II Visconti, and extended by his successor, Gian Galeazzo. Framed by a tower in each of its four corners, this was a vast, oppressive fortification with drawbridges over a deep moat, connecting to an outer wall (the Ghirlanda). In 1447 the Visconti fell from power and the populace tore down the fortifications, using the old stones to pay off debts and restore the old town walls.

Under the next ruling dynasty, the Sforza, the castle was transformed into the Corte Ducale, a sumptuous ducal residence. Beside it they constructed the Cortile della Rocchetta – a fort within a fort – and added the lofty Torre di Bona (Bona Tower). During this golden age in Milan’s history, leading literati, artists and musicians were summoned to the court. In the late 15th century, Leonard da Vinci was nominated engineer and painter to the court (see box) and Donato Bramante was enlisted as a court architect and painter.

Il Gran Cavallo

In 1482 Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan, commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to create a 7m (24ft) -high bronze horse, which was to be the largest equestrian statue ever conceived and Leonardo’s most important work. The multi-talented artist, who was busy producing city plans for Milan, a defence system for the castle, additions to the canal network and costumes for ducal entertainments, took years to complete the full-scale clay model. By the time it was finished, war with the French was imminent, and the bronze designated for the monument was cast into cannons. French troops arrived in 1499, and the colossal model was used for target practice by their archers.

In 1999, a bronze replica of the equestrian monument was erected in San Siro. This suburb of Milan, once fields and orchards, was the designated area for the original bronze. Conceived and cast in the US, the horse was sculpted according to Leonardo’s notes and drawings, and was donated to Milan in appreciation ‘of the genius of Leonardo and the legacy of the Italian Renaissance’.

In 1497 Louis XII of France claimed his right to the duchy of Milan, and the last Sforza fled into exile. Under the Spaniards the castle was used purely for military purposes, and after the French attacked the city in 1733 it fell into decline. Napoleon restored it for military use, creating a parade ground, transforming the ducal chapel into stables and the ducal apartments into dormitories.

Milan’s skyline, with Castello Sforzesco in the foreground, and the Duomo’s spires in the distance

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Plans to demolish the castle in the late 19th century were thwarted by the architect Luca Beltrami, who, in 1893–1904, restored its aspect as a Renaissance fortress and created a major museum complex within its walls.

Heralding the castle from the city side is an eye-catching fountain, a reconstruction of the Fascistic original. The Milanese nicknamed the fountain ‘tort de’ spus’, dialect for ‘wedding cake’. Start your visit at the Torre del Filarete (Filarete Tower), facing the city. Built in 1452 by the Florentine Antonio Averlino, the tower collapsed when gunpowder stored here exploded in 1521, so this is an early 20th-century copy. The gateway leads into the huge courtyard, the Piazza d’Armi, and from here to the Corte Ducale, where the Sforza dynasty resided.

Castle museums

The castle museums (www.milanocastello.it; Tue–Sun 9am–5.30pm; book online for tours of the towers) appeal to diverse tastes but the Museum of Ancient Art triumphs, with its Michelangelo masterpiece, followed by the Pinacoteca (Art Gallery), which has a fine collection of Venetian Old Masters.

The Museo d’Arte Antica (Museum of Ancient Art) on the ground floor of the Corte Ducale displays an extensive sculpture collection, from early Christian to medieval and Renaissance works. Highlights include a late Roman sarcophagus, Romanesque sculpture and Bonino da Campione’s equestrian funerary monument to Bernabò Visconti, who ruled Milan from 1354–85. The vaulted Sale delle Asse (Room 8) is frescoed with entwined laurel branches, designed by Leonardo da Vinci and executed by pupils – though much restored. Among the highlights is Agostini Busto’s lifelike Tomb of Gaston de Foix, the young commander of the French Army who died heroically at Ravenna in 1512.

Torre del Filarete

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Opened in May 2015, the Pietà Rondanini Museum (tel: 02 884 63703; http://rondanini.milanocastello.it; Tue–Sun 9am–5.30pm) is dedicated exclusively to Michelangelo’s masterpiece – Rondanini Pietà (1554–64). This evocative sculptural group was left unfinished – Michelangelo was working on it for nine years and until days before his death (aged 88). The work went through at least two different stages, as revealed by remnants from the original, notably Christ’s hanging right arm. The museum is located inside the ancient Ospedale Spagnolo (Spanish Hospital) which previously had been closed to the public.

Cooling off in Castello Sforzesco’s ‘wedding cake’ fountain

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The upper floor in the Ducal Court houses the Pinacoteca (Art Gallery), which displays Lombard and Venetian art, including works by Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini and Tintoretto. The other, more specialist, collections are devoted to furniture, musical instruments, the applied arts (including precious tapestries) and an archaeological collection of Egyptian and prehistoric works.

Savings

A three-day Tourist Museum Card can be bought online for €12 from www.comune.milano.it/cultura and includes free entry to all civic museums in Milan, including those in Sforza Castle. Another option is the MilanoCard, which includes free public transport and free entry or discounts at more than 500 Milan tourist attractions and over 20 museums, which can be purchased at www.milanocard.it. 24, 48 and 72 hour cards are available and cost €7, €13 and €19 respectively.

Parco Sempione

Stretching out behind the Castello Sforzesco is the revamped Parco Sempione 8 [map]. Once the haunt of dodgy characters and drug addicts, it is now an inviting park, complete with landscaped gardens, a vibrant design museum with an equally exciting restaurant, and even complimentary Wi-fi in the park. The Sforza’s original hunting ground here was six times the size of the present park. Napoleon had grand plans to build a monumental city centred on the park, but only got as far as the Arena and the Arco della Pace (Arch of Peace).

Arco della Pace

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Built at the northwest end of the park, this classical triumphal arch marked the start of the route to the Simplon Pass and France. It was originally named the Arch of Victories and decorated with bas-reliefs commemorating Napoleonic conquests, but work stopped with the French defeat at Waterloo in 1815. It was another 24 years before it was completed. The opportunistic Austrian emperor Francis I switched the Chariot of Peace round on top of the arch to face the centre of Milan (rather than Paris), altered the bas-reliefs and renamed the monument Arch of Peace in commemoration of the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

On the eastern side of the park, the Arena Civica, a Roman-style amphitheatre, was the venue for chariot races, festivities and even mock naval battles, using water from the canals. Seating 30,000, it is used today as a sports stadium, and as a venue for concerts and civil weddings.

The Triennale, on the western side of the park, opened in 1932 as a museum for exhibitions and the decorative arts but has been reborn as the Triennale Design Museum (www.triennale.org; Tue–Sun 10.30am–8.30pm). This is the first museum in Italy devoted solely to design. For anyone lukewarm about design, the museum is still engaging, with a playful space and a compact permanent collection ranging from the post-war period to the present day. This is matched by hit-and-miss design exhibitions. The Triennale café and restaurant is predictably trendy and serves interesting food to a critical arts crowd (for more information, click here).

Close to the Triennale, the metallic Torre Branca is Milan’s answer to the Eiffel Tower (summer Tue 3–7pm and 8.30pm–midnight, Wed 10.30am–12.30pm, 3–7pm and 8.30pm–midnight, Thu–Fri 3–7pm and 8.30pm–midnight, Sat–Sun 10.30am–7.30pm and 8.30pm–midnight; winter Wed 10.30am–12.30pm and 4–6.30pm, Sat 10.30am–1pm, 3–6.30pm and 8.30pm–midnight, Sun 10.30am–7pm; closed in bad weather). Designed in 1933 by the Milanese architect Giò Ponti as part of the Triennale exhibition, the tower has a lift that whisks you up 108m (354ft) for a panorama of the city. Back at the bottom, if suitably dressed, consider a cocktail in the flashy Just Cavalli Café, or supper in the equally kitsch restaurant, both owned by rock royalty’s favourite fashion designer, Roberto Cavalli.

Cimitero Monumentale

Cimitero Monumentale’s elaborate entrance house

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Flamboyant designer tombs and funerary monuments provide a fascinating open-air gallery at Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale 9 [map] (Piazzale Cimitero Monumentale; Tue–Sun 8am–6pm). The cemetery lies north of Parco Sempione, close to Stazione Porta Garibaldi. Dating from 1866, it is full of Art Nouveau, neoclassical and modern monuments. The focal point is the Famae Aedes (House of Fame), the resting place of illustrious Italians such as the conductor Arturo Toscanini and the novelist Alessandro Manzoni.

Restaurant options

Pulsating new neighbourhoods are springing up all around this area, but for now the most civilised dining options lie just east, in Corso Como 10, or Acanto on Piazza della Republicca (for more information, click here).

A short stroll from La Scala down Via Verdi brings you to the Brera, a chic quarter which has not sold its soul. Today, this picturesque patch of cobbled streets, cosy inns, discreet boutiques and fashionable nightspots is a reassuring choice for Milanese in search of a mellow mood. The quirky art galleries and indie boutiques still provide a hint of Bohemia. After dark this is a lively quarter. Dozens of new haunts have sprung up, from arty bars and late-night ice-cream parlours to designer cafés where you can sip an aperitivo alfresco while tucking into new-wave stuzzichini (nibbles). Yet the evocation of ‘old Milan’ survives, despite the fusion food, backchatting African bag-sellers and eccentric fortune-tellers who line Via Fiori Chiari after dark.

Pinacoteca di Brera

This quarter is also home to the Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts) and the Pinacoteca di Brera ) [map] (Brera Art Gallery, Via Brera 28; http://pinacotecabrera.org; Tue–Sun 8.30am–7.15pm, until 10.15pm on Thu; book online on www.vivaticket.it or tel: 02 9280 0361). Set in Palazzo Brera, Milan’s showcase museum possesses one of the finest collections of Italian masterpieces. The Jesuits ran a college, library and observatory here, but when the Order was disbanded in 1772, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria established the Accademia di Belle Arti. From this Academy, a core collection was enriched with works of art from northern Italian churches and convents suppressed by Napoleon. Added to the collection were representative paintings from foreign art movements.

Statue of Napoleon at Pinacoteca di Brera

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

A bronze statue of Napoleon dressed as a Roman hero greets you as you enter the inner courtyard, where a double stairway leads up to the art galleries. The collection spans some six centuries, and the rooms are roughly chronological.

The following is a selection of the masterpieces on display. The Dead Christ (c.1500) by Mantegna (Room VI) demonstrates the artist’s controlled style and mastery of dramatic foreshortening. It was painted at the end of his life and probably intended for his own tomb in the church of Sant’Andrea in Mantua. In the same room are two notable works by his brother-in-law, Giovanni Bellini: the Pietà and a beautiful Madonna and Child, painted when he was nearly 80. Room VII has portraits by some of the great Venetian masters; Room VIII has the huge detailed depiction of St Mark Preaching in Alexandria begun by Gentile Bellini in 1504 and completed after his death by his brother Giovanni in 1507.

Room IX’s Discovery of the Body of St Mark (1565) by Tintoretto shows the artist’s mastery of perspective and theatrical effects of light and movement. In the same room, Veronese’s Feast in the House of Simon (1570) was originally commissioned as The Last Supper, but the hedonistic detail was not appreciated and Veronese found himself before the Inquisition. Room X jumps to the 20th century, with the Jesi private collection of paintings and sculpture, including works by Modigliani, Picasso and Braque. In Room XIX the Madonna of the Rose Garden, by the prolific Milanese painter, Bernardino Luini, shows the influence of Leonardo da Vinci in his subjects’ faces and expressions.

Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

Room XXIV has the two most celebrated works in the collection: The Montefeltro Altarpiece (1472–4) by Piero della Francesca was painted for his patron, Duke Federico da Montefeltro, who is shown kneeling – the ostrich egg dangling above the Madonna is a famous detail, giving depth to the scene as well as symbolic value (of the Immaculate Conception); and Raphael’s serene Marriage of the Virgin (1504) evokes a sense of harmony between the architecture and the natural world. In Room XXIX Supper at Emmaus (1606) by Caravaggio is a fine example of the artist’s realism and chiaroscuro; Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss (1859) in Room XXXVII became a symbol of 19th-century romantic painting.

Churches and cafés of the Brera

Part of the charm of the Brera lies in the serendipity of galleries, churches and cafés, all tightly packed into a small, cobblestoned corner of ‘old Milan’. The loveliest church in the Brera is the Romanesque basilica of San Simpliciano (Piazza San Simpliciano; www.sansimpliciano.it; daily 7am–noon, 3–7pm). Thought to have been founded by Sant’Ambrogio in the 4th century, it was reconstructed 800 years later but – apart from the apse and facade, added in 1870 – retains its original Early Christian form. The apse has a fresco of The Coronation of the Virgin by the Lombard Renaissance painter Il Bergognone.

San Marco (Piazza San Marco; daily 7.30am–1pm, 4–7.15pm) is the largest church after the Duomo. It was dedicated to St Mark, patron saint of Venice, in gratitude to the Venetians for their part in the Lombard League, which saw off Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, when he laid siege to the city in 1162. Apart from the portal and tower, little is left of the original Gothic structure: a Baroque interior with nine decorated chapels lies behind a neo-Gothic facade.

Overlooking the cobbled Piazza del Carmine, Santa Maria del Carmine (daily 8am–6.30pm; free) was rebuilt in Gothic style in 1456 and given a mock Gothic-Lombard facade in 1880. The Baroque interior is a backdrop for art by Camillo Procaccini and Fiammenghino. In the adjoining cloister are remains of Roman and medieval funerary sculptures.

Artwork by Polish sculptor, Igor Mitoraj, outside the church of Santa Maria del Carmine

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

As for the cafés part of the equation, on the same square is the cool Marc Jacobs Café, but Cinc (on Via Formentini), has far more character while the cafés and restaurants on Via Fiori Chiari are more fun, at least after sunset (for more information, click here).

Fashion District – Northeast of the Duomo

For most visitors to Milan the main draw in this district is the chic ‘Fashion Quadrangle’, known as the Quadrilatero d’Oro or the Quadrilatero della Moda. But if fashion leaves you cold, even as a spectator sport, escape to three highly individualistic art collections, all of which provide insight into Milanese life and the minds of the high society patrons behind these quirky collections. The two best museums are the Museo Poldi Pezzoli and the Museo Bagatti Valsecchi, which appeal to different sensibilities but are equally deserving of attention. Further north, the Giardini Pubblici (Public Gardens) make a welcome break from pounding the city streets.

Santa Maria del Carmine

Dreamstime

Quadrilatero d’Oro

Fashionistas will make a beeline for the cutting-edge collections in this celebrated shopping quarter. Easily covered on foot, it is a compact, surprisingly discreet area, bordered by Via Monte Napoleone (familiarly known as Montenapo), Via Manzoni, Via Spiga and Via Sant’Andrea. All the big names are here, from Armani and Prada to Versace and Dolce & Gabbana. Prices are sky-high, but it’s worth coming just to window-shop at the gallery-like boutiques – and see the impeccably clad Milanese who frequent them. Stores range from chic little shops in beautifully preserved palazzi to large and modern fashion emporia. What’s more, you can now find discount stores even in the fashion district, with Kilo Fascion currently the best (for more information, click here).

Consider taking a break from shopping at highbrow Café Cova at Via Monte Napoleone 8, which attracts both sweet-toothed Milanese matrons and the fashion crowd. Alternatively, slip into Café Conti at No. 19 for an aperitif, or join the fashionistas at the Armani café. If you’re allergic to fashion victims, then Bice is the best upmarket trattoria in the area (for more information, click here).

In the Quadrilatero d’Oro

Corbis

Museo Bagatti Valsecchi

In and around the Quadrilatero d’Oro are a clutch of delightful ‘historic house museums’ (www.casemuseomilano.it) that dispel any notion of Milan as an impersonal metropolis. The most intimate is the Museo Bagatti Valsecchi ! [map] (Via Gèsu 5; www.museobagattivalsecchi.org; Tue–Sun 1–5.45pm), a fascinating museum housed within a neo-Renaissance palace. Brothers Fausto and Giuseppe Valsecchi, following the fin-de-siècle fashion for collecting in 1876–95, transformed two palaces into an authentic evocation of the Renaissance. The dilettante brothers lived here in private apartments but shared the drawing room, dining room and gallery of armour. Every work of art, chest or tapestry is either an original Renaissance piece or a perfect copy. Rooms have been lavishly decorated with painted ceilings, frescoes and elaborate fireplaces, while 19th-century necessities such as the bathtub are cleverly masked in a Renaissance-style marble niche.

Museo Poldi Pezzoli

Elegant Via Manzoni is lined by noble palazzi, but another unmissable historic home is No. 12, the Museo Poldi Pezzoli @ [map] (www.museopoldipezzoli.it; Wed–Mon 10am–6pm). Aristocrat Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli certainly had good taste – his palace contains an exquisite collection of art, antiques and curios. Helped by an inheritance and a coterie of craftsmen, connoisseurs and artists, Poldi Pezzoli restored the palace and filled it with his priceless treasures. He stipulated that on his death the building and contents should be accessible to the public.

The museum opened in 1881, with the Arms and Armoury (Poldi Pezzoli’s great passion) forming the core collection. To this was added 15th–18th-century Italian paintings, sculpture, Persian carpets, porcelain and Murano glass. The highlights are paintings by Renaissance masters in the Salone Dorato (Golden Salon), such as Mantegna’s Portrait of a Man and Madonna and Child, Piero della Francesca’s Deposition and St Nicholas of Tolentino and Botticelli’s Madonna and Child. But the local citizens’ favourite painting is the enchanting Portrait of a Young Woman by Pollaiuolo (1441–96), which is now the museum’s emblem.

Portrait of a Young Woman at Museo Poldi Pezzoli

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

Grand Hotel et de Milan

The Grand Hotel et de Milan at Via Manzoni 29 opened in 1863 as the Albergo di Milano. Towards the end of the 19th century, it was the only hotel in the city that offered post and telegraph services, and hence was popular with diplomats and businessmen. A stone’s throw from La Scala, it has long been a favourite among musicians and artists. The Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) stayed here from 1872 until his death, with breaks at his country residence in Sant’Agata, near Parma.

After an absence of 24 years from La Scala, Verdi made his comeback with a performance of Otello in 1887. Afterwards, the Milanese hailed the composer, gathering below his balcony at the hotel, and he sang an encore of the opera’s arias with the tenor Tamagno. In the last years of Verdi’s life, frequent bulletins about his health were posted in the hotel lobby, and whenever he was seriously ill crowds would gather outside. During his dying hours the Via Manzoni was laid out with straw to muffle the clatter of the carriages. Other eminent guests at the hotel include kings, emperors, presidents, famous artists and film stars.

Nearby, No. 10 Via Manzoni is home to the Galleria d’Italia (www.gallerieditalia.com; Tue–Sun 9.30am–7.30pm), housed in adjoining neoclassical palaces. Italian banks often own remarkable art collections and these are no exception. Together, Fondazione Cariplo and Intesa Sanpaolo showcase 19th-century art, much of it featuring Milan, by artists ranging from Canova to Hayez, Boldoni and Boccioni.

For a change of scene, stroll in the pedestrian district nearby, from the touristy, café-lined Corso Vittorio Emanuele II to Galleria del Corso, the trendy shopping gallery. Known as the Excelsior, it is home to designer fripperies as well as to Eat’s, an inviting café, bistro and food hall (for more information, click here). Fortified by a designer coffee, head north to Villa Necchi Campiglio on Via Mozart (www.casemuseomilano.it; Wed–Sun 10am–6pm) and a slice of Modernist Milan. In 1932 the socialite Necchi sisters enlisted local architect Piero Portaluppi to build them a coolly glamorous villa in the city centre. The sisters plumped for the Rationalist architect responsible for much of Milan’s cityscape and Portaluppi did them proud. The sisters were keen collectors and the villa remains a testament to the times, from glamorous 1930s furnishings to the evocative gardens, decadent pool and peaceful café (for more information, click here).

Giardini Pubblici

In this leafy, privileged district, Corso Venezia leads north to the Giardini Pubblici £ [map] (Public Gardens). These were originally designed by Piermarini in 1782, then revamped in romantic ‘English style’. Close by is the neoclassical Villa Reale (Royal Villa), once the residence of Napoleon but now home to a fittingly French art collection. The Galleria d’Arte Moderna is confusingly also known as the Museo dell’Ottocento (Museum of the 19th Century; www.gam-milano.com; Tue–Sun 9am–5.30pm), which is more accurate. The grandiose rooms make a fine frame for the succession of dreamy canvases by Renoir, Millet and Courbet. The 20th-century art has mostly moved to the Museo del Novecento (for more information, click here).The villa gardens, with lawns, a fish-filled lake and Doric temple are more secluded than the Giardini Pubblici.

The neighbouring PAC or Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (Pavilion of Contemporary Art; www.pacmilano.it; Tue–Sun 9.30am–7.30pm, until 10.30pm on Thu) is the main exhibition space for contemporary art. Devastated by a Mafia car bomb in 1993, the pavilion was reconstructed according to its original design. The Museo Civico di Storia Naturale (Natural History Museum; Corso Venezia 55; www.comune.milano.it; Tue–Sun 9am–5.30pm) is the biggest of its kind in Italy. It has reconstructions of dinosaurs and striking dioramas as well as specialist sections such as geology, mineralogy, palaeontology and entomology.

Planetario ‘Ulrico Hoepli’ in the Giardini Pubblici

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The nearby Planetario ‘Ulrico Hoepli’ (Ulrico Hoepli Planetarium; Corso Venezia 57; tel: 02 8846 3340; variable times) shows projections of the night sky on a fairly regular basis.

West of the Centre

Leonardo’s Last Supper is the star attraction of this district, an area that is also home to Sant’Ambrogio, the city’s most beguiling church, and the one most treasured by the Milanese. This was a monastic district in medieval times but today is the preserve of the bourgeoisie. The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie seeps into a residential district of secret courtyards, severe mansions and smart tearooms. The Corso Magenta, arguably Milan’s most elegant boulevard, links a series of museums.

In A Traveller in Italy (1964) H.V. Morton commented that ‘there can be few cities in the world, in which you can give the title of a great picture as a topographical direction’. He was referring to Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (Il Cenacolo) and the fact that the name of the painting is all he had to say to a Milan taxi driver to get him there. Visitor numbers saw a meteoric rise after the success of The Da Vinci Code – both Dan Brown’s best-selling novel and the film that followed. This means tickets need to be booked weeks in advance (see box).

Visiting The Last Supper

Tickets for The Last Supper can only be booked in advance, either via the call centre (tel: (+39) 02 9280 0360; Mon–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat 9am–2pm) or, more speedily, online at www.vivaticket.it. If tickets are unavailable, or you want more on Leonardo, take a dedicated Last Supper tour, bookable through the tourist office, which includes the painting, monastic church and even a tour of ‘Leonardo’s Milan’. The painting is in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie (Piazza Santa Maria delle Grazie; Tue–Sun 8.15am–6.45pm; metro Cadorna/Conciliazione. A maximum of 25 visitors at a time can pass through three acclimatisation and depolluting chambers before gaining access, and visits are restricted to 15 minutes. Audio-guides are available, as are guided tours in English, at 9.30am and 3.30pm.

Commissioned in 1495 by Ludovico il Moro for the Dominican convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, The Last Supper covers the whole width of the refectory north wall. It is a compelling mural, and despite heavy restoration over the centuries, makes for a moving experience. A masterpiece of psychological insight, the work shows the emotional reactions on the faces of the Apostles at the split second they hear Christ’s announcement that one of them is about to betray him. Their expressions of amazement and disbelief, and the motion depicted by their faces and gestures, contrast with the divine stillness of the central figure of Christ. The only figure to recoil and the only one whose face is not in the light is Judas, the third figure to the left of Christ.

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

Corbis

Restoration works, good and bad, have been hampered by Leonardo’s experimental technique in painting in tempera forte, rather than fresco – he applied the paint to dry plaster rather than applying it quickly to a wet surface. This gave him more time to complete the work, but meant that the moisture caused the paint to flake. On completion in 1498, the work drew high praise, but even in Leonardo’s lifetime it had begun to disintegrate. When the art historian Vasari saw it a generation later he described it as ‘a dazzling blotch’. Reworked in the 18th century, the painting was then badly damaged during the Napoleonic regime when the premises became a stable and the wall was used for target practice. In the following century, heavy-handed restorers managed to peel off an entire layer. Miraculously, the work survived the bombs that fell on the building in 1943. A painstakingly slow restoration process took place in 1978–99, giving rise to major controversy in the art world. Many experts consider the restored colours far too bright.

On the facing wall, The Crucifixion (1495) by Donato da Montorfano gets short shrift, especially as time in the refectory is restricted to 15 minutes. But this is also of interest to Leonardo fans, for he added the (now faded) portraits of Ludovico il Moro, the Sforza ruler, with his wife Beatrice and their children, to the painting.

Santa Maria delle Grazie

Santa Maria della Grazie

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

Such is the fame of The Last Supper that the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie $ [map] (Mon–Fri 7am–noon, 3–7pm, Sat–Sun 7.15am–12.15pm, 3.30–9pm) in which it sits is often overlooked. This lovely convent church has a superb brick-and-terracotta exterior, a grandiose dome and delightful cloisters. The church was built in Gothic style, but shortly afterwards Ludovico il Moro commissioned Bramante to demolish the chancel and rebuild it as a Renaissance mausoleum for himself and his wife, Beatrice d’Este. His plans for further building were dashed by the French occupation in 1499, and so the interior feels like two different churches: Solari’s original with richly decorated arches and vaults, and beyond it Bramante’s pure, perfect and simple Renaissance cube, with a massive dome.

Science Museum

For further proof of Leonardo’s genius visit the Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci % [map] (Museum of Science and Technology; Via San Vittore 21; www.museoscienza.org; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm, until 7pm on Sat–Sun), south of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

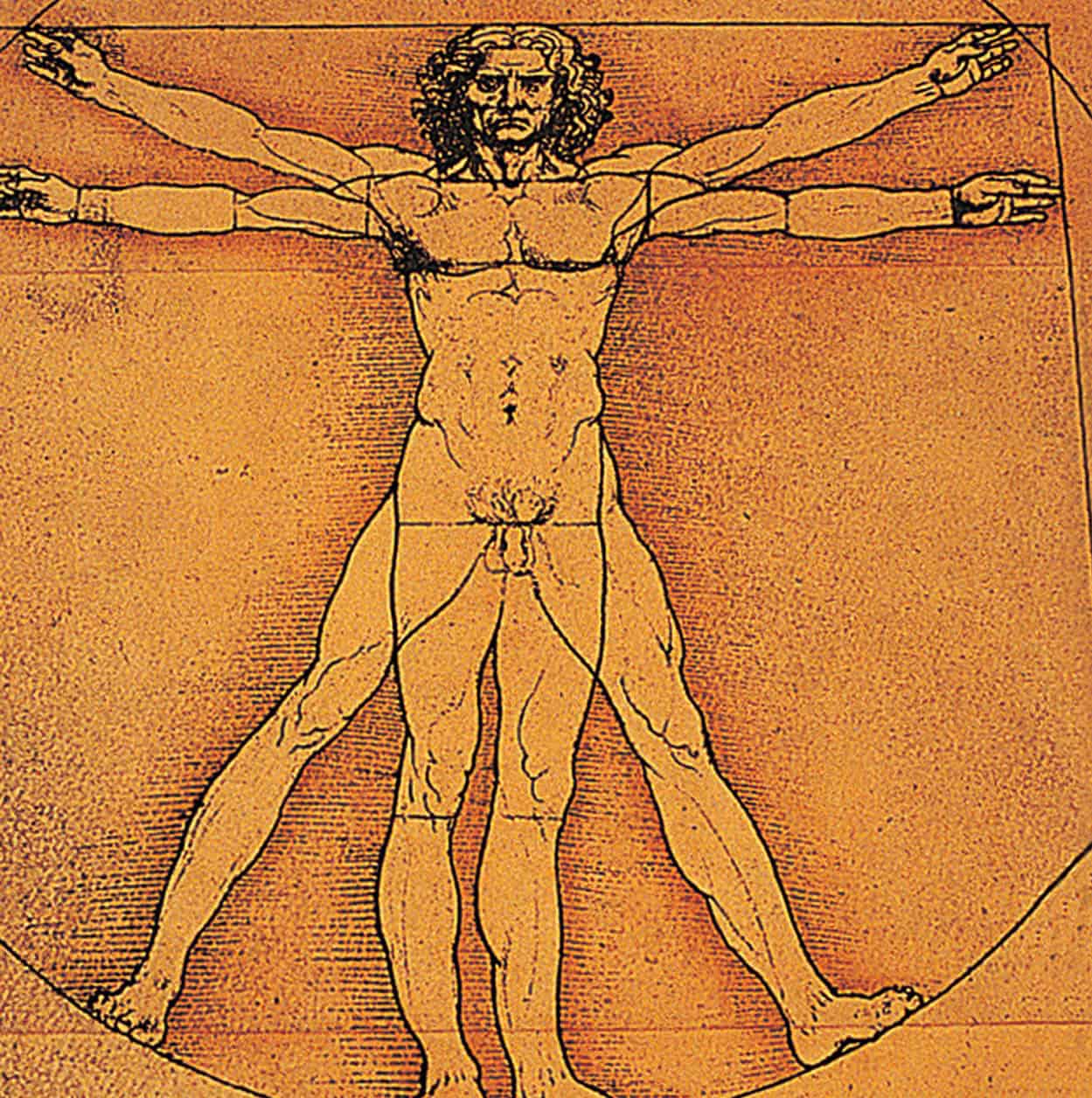

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man drawing

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

This is a daunting museum, set within the cloistered former monastery of St Vittore. Supported by interactive labs, the array of exhibits cover all the sciences, including subjects as diverse as watch-making, hammer-forging, locomotion and the workings of the internet. A star attraction is the Enrico Toti submarine (separate charge), which was built in 1967 to track Soviet submarines in the Mediterranean. In 2005 it was towed from Sicily, along the Adriatic up the River Po to Cremona, carted on wheels, and over several nights inched its way through the streets of Milan to the museum. Viewing numbers are limited to six at a time.

On the first floor the collection of models demonstrates the genius of Leonardo’s inventions. His technical drawings are reproduced along with modern interpretative drawings and descriptions. Leonardo never intended his designs to be used for construction plans, and in some cases the machines don’t work. Not that this detracts from their appeal – some of the machines were developed later with success.

Museo Archeologico and San Maurizio

On the same street as Santa Maria delle Grazie, as you head towards the centre, is the Civico Museo Archeologico ^ [map] (Museum of Archaeology; Corso Magenta 15; www.comune.milano.it; Tue–Sun 9am–5.30pm). Set among the cloisters and ruins of the Gothic Monastero Maggiore, formerly Milan’s largest convent, the museum houses Roman sculpture, mosaics, ceramics and glassware. Star exhibits are the gilded silver Parabiago Plate, with engravings of the goddess Cybele, and the Coppa Trivulzio, an emerald-green glass goblet, both dating from the 4th century. Further sections are devoted to Greek, Etruscan, Indian and medieval collections. Behind the museum lie ruins of a 24-sided Roman tower and a segment of the old town wall.

Sculpture in Civico Museo Archeologico

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Beside the Archaeological Museum, and built for the Benedictine nuns from the Monastero Maggiore, is the 16th-century church of San Maurizio (Tue–Sat 9.30am–5.30pm). The sober grey-stone facade on the street belies the vivid, restored interior with its riot of frescoes. The nuns were cut off from the congregation by a partition, and to the right of the altar you can see the tiny opening through which they received Holy Communion. The frescoes are mostly the work of the Lombard artist, Bernardino Luini, as are the lunettes on either side of the altar, which depict his patrons, Alessandro Bentivoglio, prince of Bologna, and his wife Ippolita Sforza.

A Fresco in the San Maurizio church

Alamy

Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio

Beyond is the city’s loveliest church, Sant’Ambrogio & [map] (Piazza Sant’ Ambrogio; www.basilicasantambrogio.it; Mon–Sat 10am–noon, 2.30–6pm, Sun 3–5pm). This graceful red-brick church was founded in the 4th century by Ambrogio (St Ambrose), the city’s bishop and future patron saint (for more information, click here). The church you see today – a fine Romanesque basilica flanked by two campaniles – dates from the 9th–12th centuries and became the prototype for Lombard-Romanesque basilicas. In front of it, the perfectly preserved, porticoed atrium was built as a shelter for pilgrims. The composite columns have finely carved capitals, with lively sculptures of mythical creatures and Christian symbols.

Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Inside is the beautifully carved Byzantine-Romanesque pulpit, standing over a 4th-century Palaeochristian sarcophagus. Below the 9th-century ciborium (canopy) is the jewel-encrusted gold and silver altarpiece (835), a masterpiece by the German goldsmith Volvinio. Panels on the front depict scenes from the Life of Christ, and on the back the Life of Sant’Ambrogio. To the right of the sacristy the Cappella di San Vittore in Ciel d’Oro (Chapel of St Victor in the Sky of Gold) is decorated by splendid 5th-century mosaics, depicting Sant’Ambrogio and other saints. In the crypt below the presbytery the saint’s remains share a silver-and-crystal urn with those of the martyred Roman soldiers Gervasius and Protasius.

The South: the Canal Quarter and the Ticinese

It is hard to believe that landlocked Milan was once an important port with a major network of canals. Trade on the waterways ceased in the late 1970s, and the Navigli (canal quarter) has been undergoing a transformation ever since. Galleries, inns and bars proliferate along the towpaths, and the area is now a buzzing nightlife centre, though generally sleepy by day. Between the Duomo and the Navigli lie two of Milan’s oldest and finest churches, San Lorenzo and Sant’Eustorgio. Further east, the now traffic-clogged Corso di Porta Romana was the ancient road to Rome.

The Navigli

The Navigli were key navigable waterways, linking Milan to the River Ticino, which descends from Switzerland via Lake Maggiore to Pavia and, via the Po, to the sea. Work on the Naviglio Grande (Grand Canal) started in 1177, and the waterway was initially used by horse- and oxen-drawn barges. The first 30km (19 miles) took half a century to construct and involved hundreds of men with shovels and axes. They finally reached Milan in 1272, but works came to a standstill when the Milanese opposed the project, particularly the clergy, who were charged a new tax to help finance it.

In 1359, under Galeazzo II Visconti, excavations began on the Naviglio Pavese, the canal to Pavia whose main function was to irrigate the great park surrounding the Visconti castle at Pavia. Under his successor, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the foundation stone of Milan’s Duomo was laid (1386), and the canals were then used to ship huge blocks of marble from the Candoglia quarries near Lake Maggiore to Milan. Barges travelled along the Ticino River to the Naviglio Grande and Milan’s city dockyard. Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by waterways, and one of his many tasks during his employment in the court of Ludovico il Moro, of the Sforza dynasty, was to suggest improvements to the canal network. In the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the Codex Atlanticus shows Leonardo’s scientific bent, revealing his schemes for waterways and canal sluice gates, including a double-door closing mechanism and a sluice-gate system that is still in use today.

Following the Sforza dynasty, long periods of neglect were brought about by foreign rule, wars, pestilence and earthquakes. In 1809, under Napoleon, the first section of the Naviglio Pavese became navigable, and in 1816, after 600 years, the 50km (30 miles) of the Naviglio Grande were finally completed. Added to the 101km (63 miles) of other canals and 81km (50 miles) of navigable river reaches, this formed a waterway network of 232km (145 miles). Between 1830 and the end of the century, an annual average of 8,300 barges, transporting 350,000 tonnes of trade, arrived at the dockyard of Porta Ticinese.

Canal traffic suffered with competition from railways in the 19th century, but saw a brief surge of activity during the post-war building boom. But competition from road transport finally led to the demise of canal trade; the waterways were filled in, and the last barge delivered its shipment of sand in 1979. Nowadays, the only water transport comes in the form of pleasure cruises along the few surviving canals (see box).

Stroll along the towpaths in the Navigli quarter

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Navigli today

The Porta Ticinese * [map] on Piazzale XXIV Maggio heralds the Navigli quarter. This original gateway, which formed part of the 12th-century city walls, was replaced in 1804 by the present-day monumental arch. It stands isolated in the square, surrounded by traffic.

Canal tours

Navigli Lombardi run one-hour canal cruises from April to September. Boats run regularly from Alzaia Naviglio Grande 4; tel: 02 667 9131; www.naviglilombardi.it (in Italian only).

Formerly the most insalubrious quarter of the city, the Navigli has been regenerated over the last few decades, and now has a mix of working-class and upwardly mobile residents. The industrial sites and tenement blocks have been reincarnated as desirable designer apartments, towpaths are lined with galleries, craft workshops and quirky shops, giving it a faintly bohemian air, and a host of bars, jazz clubs and restaurants have moved in. So too have festivals, fairs and markets. Apart from the weekly flea market, the huge Mercatone dell’Antiquariato is held on the last Sunday of the month from September to June, with around 400 antique dealers spreading their wares along the canal banks.

The weekly Fiera di Senigallia flea market

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Darsena (dockyard), built in 1603, used to be the hub of the Navigli quarter, where barges docked to offload their cargo. What used to be a neglected stretch of murky water was regenerated, at a cost of nearly €20 million, before Expo 2015 to become a trendy, pedestrianised area. The harbour is once again navigable and a small section of the Ticinello Canal, which was buried in the 1930s, has been reopened. The quarter comes alive on Saturdays when the stalls of the Fiera di Senigallia flea market spread out along Ripa di Porta Ticinese, further up the Naviglio Grande Canal.

Most of the Navigli nightlife takes place along the two towpaths running either side of the Naviglio Grande: the Ripa di Porta Ticinese and the Alzaia Naviglio Grande. But recently there has been a shift, with the upper end of Alzaia Naviglio Grande, closest to the Darsena, attracting a more sophisticated set, partly because of the emergence of the Zona Tortona design district on the far side of Porta Genova station. As a result, this upper stretch is lined with attractive restaurants and even a boutique hotel (for more information, click here). It also features the excellent Museum of Cultures (MUDEC; Mon 2.30–7.30pm, Tue–Sun 9.30am–7.30pm, till 10.30pm Thu and Sun), which opened in 2015 and is located in a splendid building designed by architect David Chipperfield on the grounds of the former Ansaldo factory. Besides its many ethnographic collections, this interdisciplinary centre offers cultural activities, workshops and hosts temporary exhibitions. There are also restaurants, a library, an auditorium, lecture rooms and the Mudec Junior area, where children aged 4–11 can learn about cultures from around the world in an informative yet innovative way. Fashion buffs must visit the nearby Armani Silos (www.armanisilos.com; Wed–Sun 11am–7pm, until 9pm Thu and Sat) exhibition centre. Opened in 2015 to mark the designer’s 40 years in fashion, the centre displays some of his most iconic creations, including one of Richard Gere’s suits worn by the actor in American Gigolo.

Naviglio Grande (Grand Canal)

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

By the same token, younger, funkier nightlife is moving towards the other significant canal, the Alzaia Naviglio Pavese. Barges have been converted into bars and boisterous restaurants, as well as nightclubs, jazz clubs and aperitivo bars that come and go. More of a fixture are the host of trattorie with tables set out along the banks of the canals. If you come in the daytime, though, it can be distinctly lifeless beyond the chic stretch of the Alzaia Naviglio Grande. The prettiest corner is, typically, at the chic end of the Alzaia Naviglio Grande. Known as the Vicolo del Lavandai (Laundry Lane), it is named after the old wash-houses, which retain their wooden roofs and the stone slabs where the laundry was scrubbed.

Route canal

The Cerchia di Navigli was the circle of navigable canals surrounding the city. In 1930, when canal trade was on the decline, the waterways were filled in to become Milan’s traffic-clogged ring road. But plans are afoot to restore the waterways to something of their former splendour.

The Ticinese district

North of the Navigli lies the funky Porta Ticinese district. Once a dormitory suburb for Milanese factory workers, it is now a vibrant young designer district as well as being home to several significant churches. The Corso di Porta Ticinese has a friendly, alternative feel, helped by a mix of everyday and bohemian shops, and enlivened by the clatter of trams running close by.

The two great basilicas of the Ticinese quarter lie just east of the main Corso di Porta Ticinese. Sant’Eustorgio ( [map] (Piazza Sant’Eustorgio; Mon–Sun 7.45am–6.30pm), distinctive for its lofty bell tower, has Early Christian origins, but was destroyed by Frederick Barbarossa in 1162 and rebuilt over several centuries. Highlights of the church are the private Renaissance chapels, and most notably the beautiful little Cappella Portinari (1462–6), which can only be seen by visiting the Museo di Sant’Eustorgio (daily 10am–6pm; combined ticket with Museo Diocesano, and the Cappella Sant’Aquilino at San Lorenzo, for more information, click here).

Lavish marble sarcophagus in the Cappella Portinari

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Similar to Brunelleschi’s Cappella Pazzi in Florence, this simple chapel was one of the first Renaissance works in the city. Traditionally attributed to the Florentine Michelozzo, it is now believed to have been designed by a Lombard architect working in Tuscan circles. The chapel was commissioned by Pigello Portinari, a Florentine nobleman and agent of the Medici Bank in Milan, to house the relics of St Peter Martyr – as well as his own. St Peter Martyr (Pietro da Verona) was an Inquisitor who persecuted the Cathars, one of whom took revenge and killed him in 1252. His relics lie in the lavishly carved marble sarcophagus (1339), a masterpiece by Giovanni Balduccio from Pisa. The saint’s skull is protected in a silver reliquary in the chapel to the left of the altar. Stunning frescoes by the Tuscan artist Vincenzo Foppa decorate the chapel and depict scenes from the Life of St Peter Martyr and the Virgin Mary.

The basilica was built to house the supposed relics of the Magi. These are contained in a Roman sarcophagus in the Chapel of the Magi in the right-hand transept of the main church. During the annual Corteo dei Magi procession on 6 January (Epiphany), the relics are carried with great ceremony from the Duomo to Sant’Eustorgio. Beside Sant’Eustorgio, the Museo Diocesano (Corso di Porta Ticinese 95; www.museodiocesano.it; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm) is arrayed on three floors of the Dominican convent and cloisters, and showcases 320 works from Sant’Ambrogio (for more information, click here) and other churches in the diocese. Unlike many diocesan museums, which are dull and dusty, Milan’s has been renovated and feels like a stylish new art gallery. The works date from the 6th to the 19th centuries, and, as well as religious paintings, there are sculptures, chalices and jewellery Don’t miss the Fondi Oro collection – exquisite Tuscan and Umbrian altarpieces, all with a gold background.

A rose-lined path through the Parco delle Basiliche (Park of the Basilicas) links Sant’Eustorgio and San Lorenzo. For many centuries public hangings and torture took place here, while tanners’ workshops created a foul stench. Today it is a pleasant park, which affords the best views of the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore , [map] (Corso di Porta Ticinese 39; www.sanlorenzomaggiore.com; daily 7.30am–12.30pm, 2.30–6.30pm). After the Duomo, this is the second-largest church in the city, distinctive for its huge central dome and the melange of architectural styles. It is also the oldest surviving church in the city, founded in the 4th century as an early Christian church, remodelled in Romanesque form in the 13th century, and reconstructed in the 16th century after the collapse of the dome in 1573. The facade is the newest addition, dating from 1894.

Statue of emperor Constantine outside the church of San Lorenzo Maggiore

Jerry Dennis/Apa Publications

The 16 lofty Corinthian columns on the square in front of the church came from a Roman temple, and were probably erected here as a part of a portico for the original basilica, hence the alternative name for the church, San Lorenzo alle Colonne. In front of the church is a 1942 statue of Constantine the Great, who issued the Edict of Milan, granting freedom of religion to Christians in 313, before the church was built.

Inside the church the Early Christian octagonal plan, though remodelled in the 16th century, has essentially been preserved. On the right, the Cappella Sant’Aquilino was built as an imperial mausoleum and retains some beautiful 5thcentury niche mosaics. At the altar, an elaborate silver-and-crystal casket contains the remains of Sant’Aquilino, while a small stairway to the left of the altar descends to the imperial-era foundations.

Corinthian columns in front of San Lorenzo Maggiore church

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Building material for San Lorenzo was thought to have been salvaged from the nearby Roman Circus and Amphitheatre. Remnants of the latter can be seen at the Parco Archeologico e Antiquarium Alda Levi (Archaelogical Park and Antiquarium, entrance at Via de Amicis 17; Tue–Fri 9.30am–6pm, until 4pm on Sat and in winter; free). The remains of this huge four-storey coliseum were discovered during roadworks here in 1931. Within the park, the Antiquarium (Tue–Sat 9.30am–2pm; free) displays architectural finds from the area, and to liven things up, shows excerpts from such films as Spartacus and Gladiator. One real-life gladiator, Ubricus, died at the age of 22 having fought 13 times here.

Excursions from Milan

With excellent road and rail links, Milan makes a good starting point for excursions in the Lombardy region. The lakes and mountains are surprisingly close. By train you can be in Stresa on Lake Maggiore, Como on Lake Como or Bergamo within an hour.

The following are briefer excursions from Milan. The Abbazia di Chiaravalle and Monza are both on the city outskirts; Pavia and its Certosa are further away but justify a whole day’s excursion.

Chiaravalle Abbey

In 1135 French Cistercian monks drained the marshland southeast of Milan, transforming it into rich agricultural land, and built the splendid Abbazia di Chiaravalle ⁄ [map] (Chiaravalle Abbey, Via Sant’Arialdo 102, 7km/4 miles southeast of Milan, metro M3 Corvetto, bus No. 77 from Piazza Medaglie d’Oro; www.monasterochiaravalle.it; opening times vary; guided tours Sat and Sun at 3 and 4pm). The founder was St Bernard, who was the Abbot of Clairvaux in France (Chiaravalle in Italian), to which the new abbey was affiliated.

The church was rebuilt in 1150–60, altered over the centuries, and disbanded under Napoleon. A lengthy restoration was completed in the early 1950s, and Cistercian monks finally returned to the abbey. A blend of Lombard Romanesque and French Gothic, the church is notable for its striking terracotta-and-marble campanile, internal Renaissance and Baroque frescoes, and finely carved wooden choir and Gothic cloisters.

Pavia

Emperor Constantine

Dreamstime

The ancient university town of Pavia ¤ [map] lies on the banks of the River Ticino, 36km (22 miles) south of Milan. Long ago it was one of the leading cities in Italy, reaching its zenith between the 6th and 8th centuries as capital of the Lombard kingdom and site of the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperors. During the 14th century, the city was subdued by the Visconti dynasty of Milan who built the great Certosa di Pavia (Carthusian monastery), the Castello Visconteo (Visconti Castle), and founded the city’s university, one of the oldest in Europe, noted for law, science and medicine.

Pavia’s university is one of Europe’s oldest

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Pavia today is a pleasant town of cobbled streets and squares, Romanesque and Gothic churches, feudal towers and palazzi. The enormous 19th-century dome of the Renaissance Duomo dominates the centre. Amadeo, Leonardo and Bramante were among its architects, but today it is a disappointing hotchpotch of styles. The pile of rubble beside it is all that remains of the medieval tower, which collapsed in 1989, killing four people. The town’s finest church is the Basilica di San Michele, a masterpiece of Lombard-Romanesque. The church witnessed the coronation of kings here during the Middle Ages, the last being Frederick Barbarossa in 1155. The glorious facade, in mellow sandstone, is decorated with fascinating (but sadly faded) friezes of beasts, birds, mermaids and humans; there are more carvings inside on the columns, which are better preserved. The austere Visconti Castle, a mere shadow of the former ducal residence, contains the Civic Museum (www.museicivici.pavia.it; Jul–Aug and Dec–Jan Tue–Sun 9am–1.30pm, rest of the year Tue–Sun 10am–5.50pm), with collections of paintings, sculpture and archaeology.

Certosa di Pavia

The great Certosa ‹ [map] (Carthusian monastery; tel: 0382 936 911; www.certosadipavia.com; May–Sept Tue–Sun 9–11.30am and 2.30–6pm, Oct –Apr until 4.30pm; for guided tours, arrive one hour before closing time; free, donations welcomed) lies north of Pavia, among fields which were the former hunting ground of the Visconti. One of the most decorative and important monuments in Italy, it was founded in 1396 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti as a mausoleum for himself and his family. However, it was not completed for another 200 years. The Carthusian Order was suppressed in 1782, and since then the monastery has had a chequered history, closed for long periods or variously occupied by Cistercian, Carmelite and Carthusian monks. In 1866 it was declared a national monument, and since 1968 a small community of Cistercian monks have occupied the Certosa.

Encrusted facade of the Certosa

iStock

Creating a striking impact as you enter the gateway is the multi-coloured marble facade, encrusted with a proliferation of medallions, bas-reliefs and statues of saints and prophets. The monument marks the transition from late Gothic to Renaissance: the interior is essentially Gothic, created by some of the same architects and artisans who worked on Milan’s Duomo; the lower level of the facade dates from the 15th century, and the plainer upper facade from the first decades of the 16th century.

The soaring interior is a treasure house of Renaissance and Baroque works of art. Outstanding among them are the funerary monument of Ludovico il Moro and his wife Beatrice d’Este, the mausoleum of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, frescoes by Bergognone in the transept, chapels and roof vaults, the marquetry in the choir stalls, the altarpiece by Perugino and the Florentine triptych, made of hippopotamus teeth and other animal bones, in the Old Sacristy. Visits end at the Certosa shop selling the local Carnaroli rice, honey, herbal remedies and liqueurs.

Regular trains and buses link Pavia with Milan. The Certosa, 8km (5 miles) to the north, has its own train station and bus stop, but both are a 1.5km (1-mile) walk from the monument, mostly along a main road, which can be tiring on a hot summer’s day.

Monza

Duomo di San Giovanni, Monza

Fotolia

Once an important medieval town and the site of the coronation of many Lombard kings, Monza › [map] today merges with the industrial suburbs of northwest Milan and is best-known for Grand Prix motor-racing. The town has been revamped for Milan’s Expo 2015. Even so, Monza’s centrepiece remains the Gothic Duomo di San Giovanni (Cathedral of St John; www.duomomonza.it), founded by the Lombard queen Theodolinda in 595 and rebuilt from the 13th–14th centuries. The Cappella di Teodolinda (Theodolinda Chapel), frescoed with scenes from the life of the queen, contains her sarcophagus and the gem-studded ‘Iron Crown’, which was used for the coronation of 34 Lombard kings, from medieval times to the 19th century. The last was Ferdinand I of Austria in 1836, while the penultimate was Napoleon, who assumed the throne of Italy in Milan’s cathedral in 1805. Legend has it that a nail within the crown came from Christ’s cross – hence the name ‘Iron Crown’. Theodolinda-related treasures are kept in the cathedral museum, Museo Serpero, including her own bejewelled crown.