Modern colonial states found themselves in one of two anxiety-provoking situations. In what Philip Curtin calls “true empire” colonies, small numbers of officials from the imperial center attempted to rule overwhelming numbers of indigenes, who responded with varying degrees of cooperation and resistance. In what Curtin calls “settlement empire” colonies, relatively small numbers of settlers from Europe expropriated land from indigenous peoples, either by conquest or submission or through the decimation of local populations as a result of introduced diseases.1 In its early stages, the southern African British colony of Natal combined characteristics of both colonial models. In the late 1830s, Dutch-speaking emigrants from Britain’s Cape Colony occupied the area and carved out a niche for themselves in the region by defeating the Zulu kingdom, whose heartland lay to the northeast. A few years later, Britain annexed the territory claimed by the Dutch-speakers. Britain then encouraged the immigration of Anglophone white settlers in a movement comparable to the immigration of 1820, when Cape officials encouraged Anglophone settlement along the eastern frontier of its recently acquired Cape Colony. But Natal’s officials continued to rule over an indeterminate number—perceived to be rapidly growing—of Africans who had never formally submitted or been conquered and who were not especially vulnerable to European-borne diseases. From the earliest stages of white settlement and rule in Natal, then, officials and settlers alike frequently expressed their worries over the origins, identities, customs, and location of indigenous people. These anxieties reflected fundamentally ambiguous attitudes about the presence of Africans and the expansion of African populations.

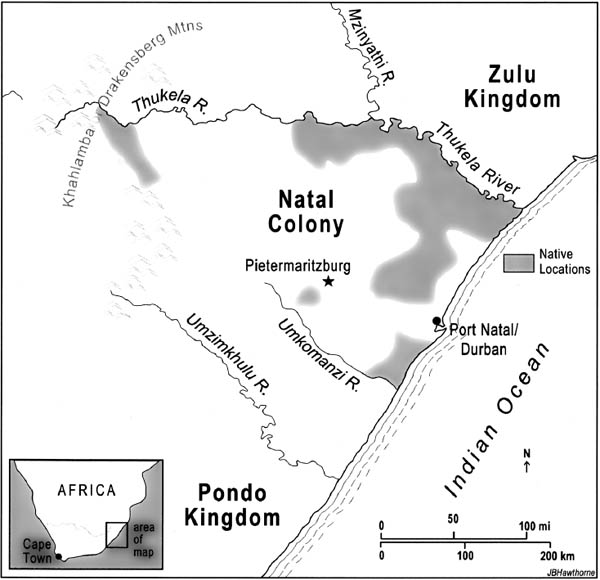

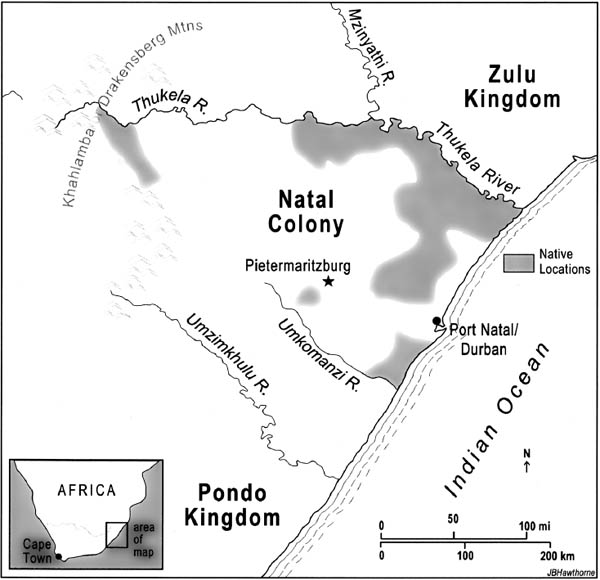

Figure 4.1. Colonial Natal

The colonies and settler republics that became today’s South Africa considerably predated the imposition of European empires on most of Africa in the late nineteenth century, and they differed from all but a handful of the later colonies by encouraging permanent European settlement. The southern African colonies and settler republics were all descendants of the Cape Colony, which became part of the British Empire in 1806, during the Napoleonic Wars. The Cape Colony was in turn an outgrowth of the Dutch East India Company’s seventeenth-century settlement at Cape Town, where the Mediterranean climate enabled the cultivation of grains and fruits in the European repertoire just as it precluded the introduction of standard African crops. Although the first century and a half of white settlement in the Western Cape had resulted in the political and social devastation of indigenous Khoisan-speaking herding and foraging populations, by the time the British arrived on the scene considerable numbers of white and brown settlers were penetrating inland, raiding cattle, and seeking labor from larger-scale Bantu-speaking farming and cattle-keeping societies to the east and north. On the eastern frontier, this migration of settlers led especially to a series of wars between colonial forces and Xhosa-speaking peoples.

In addition, the British arrived in southern Africa in the midst of their own debates about slavery and freedom. Although the debates centered mainly on sugar-producing islands in the Caribbean, they played out in the empire as a whole. As a result, the British takeover of the Cape Colony had a significant impact on labor polices, and the empire’s ability to mobilize decisive military power allowed the colony to strengthen or expand its borders in the drive to absorb more land and labor. Both Britain’s abolition of the international slave trade in 1807 and its emancipation of slaves in 1838 therefore had significant impacts in southern Africa, as settlers were forced increasingly to look to local populations for labor. At the same time, those local populations stood in the way of the settlers’ desires to exert exclusive control over vast stretches of land.

Natal was no exception in regard to colonial anxieties and ambiguities about Africans within and beyond colonial borders, and this is reflected in a key problem in the historiography of early colonial Natal. White observers broadly agreed that from the late 1830s, after white settlement of the region that became Natal colony, the African population increased rapidly. They disagreed, however, about whether this population growth stemmed from communities returning to lands they had fled in the “wars of Shaka,” who founded the Zulu kingdom in the generation before white occupation, or whether these people were mostly new immigrants seeking refuge from the Zulu kingdom or other nearby polities. These questions—and the underlying issues of land, labor, and not least of all taxation—consumed colonial officials trying to craft and implement policies related to land tenure for whites, the establishment and development (or not) of reserves for Africans, and methods of establishing authority and maintaining peace. These questions pertained to a colony that was open to white settlement but overwhelmingly populated by Africans who remained relatively independent economically for several decades and on whose productive capacities the colony depended for much of its revenues and food supply.2 Officials and settlers sought to define who was within the empire and what rights and obligations that status carried. Whites viewed the Africans in their midst and nearby as culturally alien but threateningly indigenous. Their alterity could be used as a reason to exclude them from land whites wished to claim, even as their numbers could be tapped for supplies of labor and/or streams of revenue. Meanwhile, their local knowledge, alien culture, and feared ability to mount organized violence threatened the colonial enterprise with undue expense or even potential collapse.

Like most historical questions, the questions surrounding the movements of population into and out of Natal in the early nineteenth century are much more complicated than at first imagined. There are a number of subsidiary issues. For example, to what extent was the region that became the colony of Natal “devastated” or depopulated during Shaka’s reign in the neighboring Zulu kingdom? Between the initial immigration of Dutch-speaking farmers (and their “colored” servants) from the Eastern Cape and just after the British annexation, evidence suggests that there were some large-scale movements of people into the region. To what extent were they composed of people previously displaced from Natal or their descendants? Was the rise in African population in the first years of white settlement and British colonization as dramatic as contemporary officials suggested? It is impossible to give definitive or precise answers to these questions. The best we can do is to consider the evidence and interrogate it in new ways. This examination will help us understand the demographic anxieties of a nascent colony on the outer fringe of the British Empire.

In early British-ruled colonial Natal, officials were consumed with questions of immigration and emigration. They sought to classify occupants of the colony not only by race and religion but also, with respect to blacks, by whether they should be counted as “aboriginal” to the territory or whether they were “refugees” from the neighboring Zulu kingdom or other areas beyond the borders. Natal became a colony in 1843 when Britain annexed the “district of Port Natal,” eventually defining its borders as lying between the Thukela, Mzinyati, and Mzimkhulu rivers and the Drakensberg (uKhahlamba) Mountains.3 Five years earlier, Dutch-speaking emigrants from the eastern seaboard of Britain’s Cape Colony had entered the region and clashed with the Zulu kingdom, which claimed authority over at least part of the area. After the Dutch-speakers (also known as Boers, whose descendants call themselves Afrikaners) defeated the Zulu at the battle of Ncome (Blood) River in December 1838, Zulu king Dingane was toppled by his brother Mpande, who assumed the throne with the support of the Boer forces. In return for that support, Mpande agreed to cede most of the area that became Natal, and the Boers proclaimed a state called the Republic of Natalia.4 The British, however, kept a close eye on the region. British traders had been settled at Port Natal (later Durban) since the mid-1820s and had long urged the British government to take a more active role in the region in order to free them from dependence on the Zulu royal house.5 Port Natal’s bay was the best harbor between Delagoa Bay (in present-day Mozambique) and the Cape Colony, so an empire based on free-trade imperialism that already had a strong colonial foothold in the subcontinent and that wished to protect the sea routes to its prime territorial possession—India—could not afford to ignore either the port or its hinterland. The British were also concerned about the activities of those they called Dutch Emigrant Farmers (the Boers), whom they still considered British subjects. Boer raids on African communities in and near Natalia, leading to enserfment of children from raided communities as “apprentices,” flew in the face of the recent emancipation of slaves in the British Empire.6 The Natalians’ plan to remove a large proportion of the African inhabitants to an area beyond their southern border also excited British nervousness about the potential destabilizing influence on the Cape Colony’s already war-torn eastern frontier.7

During Natal’s first decade as a British colony, official reports repeatedly cited a rapid rise in the African population to about 100,000, attributing the increase to immigration. In 1852, Henry Cloete, the recorder, put it as follows:

I made every possible inquiry both from the Dutch and British Emigrant farmers as to the numbers of what might be termed aboriginal tribes they had found on their arrival in the District. . . . In round numbers the really aboriginal kaffirs found in the District at that time appeared to have been about 5000 or 6000. . . . I made a broad distinction between the aboriginal kaffirs and the interlopers or Zulus and others who had come for safety into the District.8

Cloete’s testimony shows that officials believed they were being inundated by immigrant Africans. The 1852–53 Native Affairs Commission argued, following a proposal forwarded from the colony’s by Diplomatic Agent to the Native Tribes (later Secretary for Native Affairs) Theophilus Shepstone, that 30,000 or 40,000 Africans should therefore be removed from Natal.9 They attributed the rush of immigration to their own establishment of peace in the region, which they saw as a restoration of conditions prevailing before Shaka’s reign (c. 1816–28). They understood Shaka’s Zulu kingdom to have launched a period of searing warfare that had caused survivors to flee to other regions. Given the renewed peaceful conditions, they believed, African communities were crossing mountains and rivers in order to settle in the colony. Some of the migrants were returning to lands from which they had been previously displaced by Zulu raiding—though the Commission report also held that “Kafirs have little attachment to any particular locality.” Others were new refugees from despotic rule within the Zulu kingdom, northeast of the colony’s Thukela River boundary.

Whatever their source, officials saw the migrants as a problem that impinged on their project to establish colonial order. Although immigrants were a potential source of labor, they were also among the many claimants to land. Claimants included Dutch-speaking settlers who, continuing a tradition established by cattle ranchers in the early colonial Cape, had staked out vast claims to land just before British annexation as well as mission societies and established African chiefdoms and communities. Added to this mix was an influx of about 5,000 sponsored immigrants from Britain between 1849 and 1852, mostly artisans, traders, and farmers.10 In this situation, colonial officials wished to stem the flow of African immigrants, and they even gave serious consideration to removing a large proportion of Africans to an area beyond the colony’s southern border, much as their Boer predecessors had planned.

Shepstone’s removal plans, which I have discussed at length elsewhere, grew out of these competing demands for land.11 In 1847, the colony’s lieutenant governor, Martin West, appointed a “Locations Commission,” headed by Shepstone, to designate portions of the colony for exclusive African occupation in order to limit African numbers on and entitlement to white-claimed land. The commission recommended a system in which each location—or reserve, as these lands were later called—would be ruled by a white superintendent in charge of African chiefs. The locations would also feature such staples of interventionist “civilizing” colonialism as missions and industrial schools, and they would nurture a Westernizing peasant class. Although the colonial government did designate locations, the rest of the plan was immediately shelved as entailing large expenditures that the fledgling colony could ill afford and that the imperial government was unwilling to subsidize. Frustrated in his attempts to implement such a plan, which he considered essential for the long-term development of the colony’s African subjects, and worried that the influx of white settlers might lead to demands for dismantling the reserves, Shepstone proposed a series of plans for removing portions of the African population from the colony. In the 1854 version, he offered to lead up to half of the Africans in Natal to an area south of the colony. There, he would be the paramount ruler and would implement the civilizing plans the colony had failed to embrace. His subjects would be productive peasants and craftspeople, and they would also form a labor reserve for the neighboring colony. Although the 1852–53 Native Commission endorsed an earlier version of this plan and although the plan received a tentative go-ahead from the lieutenant governor, higher imperial authorities vetoed it as an unwarranted and potentially expensive expansion of British sovereignty.

By the mid-1850s, the colonial government’s policy toward Africans developed into what nonetheless came to be known as the Shepstone system. This system entailed rule through chiefs and customary law, reserves, and direct and indirect taxation but only minimal efforts toward the “civilization” of Africans except in the relatively small and scattered reserves assigned to Christian missions. But as both white and black populations continued to grow and as land speculators came to dominate much of the land outside the reserves, officials continued to worry about the sources and histories of African communities.

The debate, so crucial for colonial actors in the 1840s and 1850s, has also been reflected in the historiography of the region since the late nineteenth century. Looking at this problem through its historiography can help us think about how to interpret problems of insider and outsider status within the empire and in Natal, and it also helps us analyze colonial ambivalence about the presence and provenance of African subjects.

In the mid-1960s, Edgar Brookes and Colin Webb dated the refugee problem to the years before British annexation, under the trekkers’ Republic of Natalia: “The scattered tribes had emerged from hiding and many were crossing over from Zululand into Natal, though not on as large a scale as in the [postannexation] years 1843–5.” As a result, the Volksraad, or settler governing body, passed a law limiting the number of squatters on each trekker farm to five families. In 1841, the Volksraad proposed to remove the surplus of Africans to an area south of the republic. This prospect gave the British one of the pretexts for annexation two years later, though ironically, as we have seen, Shepstone, as an official of British colonial Natal, would make a similar proposal only a few years later.12 In 1843, after the British declared Natal to be under their jurisdiction but before they established a British administration, 50,000 refugees are said to have arrived in the colony from Zululand as a result of political disturbances in the kingdom.13 Brookes and Webb claim that this flood of refugees added to a steady stream coming before and after it. Although the trekkers saw the immigrants as “Zulus,” Brookes and Webb, picking up a theme that goes back at least to George McCall Theal in the late nineteenth century, argued that some were merely returning to areas from which the forces of Shaka’s Zulu kingdom had displaced them.14

Theal divided the Africans of Natal into three groups: those present “before the wars of Tshaka” who had never left, those driven out by Shaka who returned after the advent of white settlers in 1838, and “refugees” not from Natal who had arrived after 1838.15 The apparently uncontrolled immigration of Africans, combined with the colony’s initial failure to confirm title to trekker land claims, led to a steady out-migration of Dutch-speakers. Brookes and Webb go on to argue that Shepstone’s “locations” policy was the inevitable result of the large number of Africans in the colony, which they put at 100,000 in 1845, without citing sources for their estimate. Shepstone is said to have coaxed “from 80,000 to 100,000” of them into vaguely defined areas set aside as locations in 1847. For the next several years, much political discussion in Natal revolved around the size of the locations, which white settlers, new and old, saw as using labor they deemed rightfully theirs.16

Writing in 1971, just five years after Brookes and Webb, David Welsh emphasized the importance of these demographic questions, taking them up as the central issue of the short introduction to his book arguing that the system of native administration in Natal colony established the “roots of segregation” and apartheid in South Africa.17 Welsh summarizes the apparent history of the rapid growth of African population in Natal:

The Voortrekkers and most of the English colonists who came to Natal in the 1830s and 1840s believed that the territory contained only very few Africans who could legitimately claim to be aboriginal inhabitants. Numerous witnesses lent credence to this view. . . . In 1838, estimates of the African population of Natal varied from 5,000 to 11,000 [citing Shepstone’s evidence to the 1852–53 Commission]. In October 1839 Mpande revolted against the Zulu king, Dingane, and crossed the Tukela [sic] into Natalia “with fully half of the Zulu population.” Delegorgue estimated the number at 17,000 [citing the 1883 Native Laws Commission and John Bird]. By 1841 the African population of Natal was estimated at between 20,000 and 30,000, and by 1843, when the British Commissioner, Henry Cloete, commenced his investigation into land claims, at between 80,000 and 100,000.18

The implication of this summary is that there was a meteoric rise in the numbers of Africans in the colony between 1838 and 1843. However, it is not possible to glean from the evidence any firm conclusions about how many Africans lived in the area that became Natal at any particular moment in the nineteenth century. A census was not even attempted until the 1880s. Therefore, it is impossible to give precise parameters to white claims of rapid increase in that population in the early years of colonization, though officials collected what evidence they possessed in connection with a Select Committee considering “documentary tribal titles.”19 What evidence they had was self-serving and necessarily portrayed in round numbers. Though the numbers presented do not correspond precisely to actual people, they certainly indicate some movement of people. More important, they reflect colonial ambivalence about African subjects and neighbors.

As Welsh argues, the idea that most Africans in the colony were “refugees” without legitimate claims on the land was to have important ramifications for Natal’s land policies. A page later, however, Welsh asserts that the refugee premise was decisively refuted by later research in oral history by Shepstone. Shepstone’s evidence suggested that Natal had been “thickly inhabited” before Shakan times; warfare emanating from the Zulu kingdom had later depopulated the region. Shepstone concluded that the people flowing into Natal after the beginnings of substantial white settlement in 1838 were “aboriginal inhabitants” rather than alien refugees.20

This idea that Natal had been depopulated by Zulu war parties forms a central premise of what John Wright has called the “mfecane stereotype” that pervaded southern African historiography until the mid-1990s.21 Norman Etherington’s recent Great Treks provides a useful summary of the unraveling of the idea of “the mfecane” as a result of the work of Wright, Julian Cobbing, and other historians.22 The mfecane debates have had two major implications. First, scholars have decentered the Zulu kingdom and an all-powerful Shaka as the motors of alleged massive violence and population displacements across early nineteenth-century southern Africa. Second, they have begun reintegrating colonial and African histories that had been segregated by apartheid conceptions of history and by an academic Africanist tradition dating from the 1960s that sought to valorize African agency and capacities for empire building. Leaving aside Etherington’s conclusions about the wider region in this period,23 his discussion of Natal shows that the idea of “devastation” resulted from the self-interested claims of white settlers, combined with a British assumption that disturbances in areas east of the Cape frontier resulted from people being driven south by Shaka. James Stuart’s Zulu informants, circa 1900, further reinforced these ideas. Heirs of both supporters and opponents of Shaka agreed that he was a fearsome and unprecedented warrior king. However, the evidence now suggests that there were large states in the region before Shakan times, showing that Shaka’s state was not unprecedented and that the effects of Zulu power in Natal were less severe and less direct than accounts such as those of the early settlers had indicated.24 Timothy Keegan argues that the British annexation of Natal itself points to the fallacy of the “empty land” idea: “Fears of destabilization grew out of the evident fact that large numbers of Africans inhabited the territory that the trekkers settled in, despite the self-serving myth that it was an empty land.”25

Many scholars have explored the notion of “empty” or “vacant” land as a foundational justification of colonialism in southern Africa. For instance, Julian Cobbing’s article that initiated the mfecane debates argues, in reference to the British traders at Port Natal, that “mendacious propaganda was insistently relayed back to the Colony that Natal had been totally depopulated by the Zulu.”26 In a broader sense, Cobbing argues that the idea of a depopulating series of wars—the mfecane—in the early nineteenth century provided convenient cover for white settlement and dominion over southern Africa. Clifton Crais points to the larger white “myth of the Vacant Land” asserting that whites and “Bantu-speaking Africans” arrived in South Africa about the same time.27 A text favored by the apartheid government in the 1970s promoted this idea quite directly. “The Afrikaner cattle-farmer advanced . . . until in 1770 at the Great Fish River he encountered the vanguard of the Black or Bantu peoples who, during the course of centuries, had been migrating slowly southwards on a broad trans-continental front.”28

Crais lays blame for this myth at the door of Theal, “the acknowledged grandfather of South African history.”29 Theal, however, drew on earlier settler constructions that emerged in the context of frontier wars and a growing discourse of black barbarism. At the time of the 1834–35 war on the Eastern Cape frontier, Crais argues, the settler press displaced the self-knowledge of an imperialist colonial society by asserting that African opponents were “an expansive, conquering and violent people,”30 which was, rather, an excellent description of colonial forces in southern Africa. Like Cobbing, Dan Wylie argues that the white pioneers of Natal engaged in similar displacements by asserting the idea of “depopulation” of the territory under Shaka. The empty-land claim of one such pioneer, the Port Natal trader Henry Francis Fynn,

is contradicted in his own and other accounts. He claims that the 225 miles between Port Natal and the Mpondo (a doubling of the actual distance) contained “no inhabitants” and that only north of the port could the marauding Zulus plunder grain. This is contradicted, for example, by James King’s account of the immediate vicinity of Port Natal . . . in which King notes that “Indian corn” was being grown there “in abundance.”31

Since Natal, both as a Boer settlement and as a British possession, was a political offshoot of the Cape Colony, myths of depopulation during the so-called wars of Shaka and a wider notion of supposedly empty land in southeast Africa were common currency by the time of the British annexation of Natal in the 1840s. The myths, enhanced as Etherington argues by faulty mapmaking in the 1820s and 1830s, carried over from two centuries of white settlement in the Cape Colony. They now circulated more rapidly through the nascent press of a self-consciously modern British colony and continued to be generated during the early decades of British rule by, for instance, the publication of Fynn’s heavily reedited diary.32

Keletso Atkins takes up the issue of the influx of “refugees” into Natal in connection with her investigation of labor in colonial Natal. Writing during the early stages of the mfecane debate, she notes the critique of the devastation theory but nevertheless seems to accept that there was a significant displacement of population from late precolonial Natal, repeating the main essentials of the story of population movements outlined in Brookes and Webb.33 She is more concerned, however, with what happened to people coming into Natal in the 1840s and 1850s. During the first two decades after the British annexation of Natal, she argues, “the central focus of foreign and domestic relations in the region consisted of attempts by both the English and [Zulu king] Mpande to staunch the outward surge of people and cattle from Zulu country.”34 In order to stem the flow of people, Natal’s officials agreed by the mid-1840s to restore to Zululand any cattle arriving with refugees. Implementing this plan, however, proved difficult. In 1854, the colony adopted a law that was uncomfortably similar to the disguised slavery practiced by the Boers in the name of “apprenticeship,” through which Boer communities had long absorbed orphaned or abducted Africans as dependent workers. The Natal policy required able male refugees entering the colony to labor for settlers for three years. The settlers hoped this policy would both reduce the volume of the refugee flow and help solve the perceived labor shortage in the colony. It would also have the convenient side effect of depressing wages. However, it turned out that the nascent colony lacked the coercive power to implement such an ordinance on a wide scale.35 The key question for Atkins is what drove the flow of refugees into Natal. She argues that although some were seeking asylum from persecution, a “great majority” were from communities that were bent on reestablishing themselves in Natal in the wake of the partial breaking up of Zulu power in the 1830s. This is a plausible argument, but the only evidence Atkins cites in support of it is an 1864 memorandum from Shepstone referring to the influx of a large number of men with Mpande during the Zulu kingdom’s “breaking of the rope” in 1839–40, and the citation makes it nearly impossible to find the referenced document.36 She also speculates extensively on efforts by immigrants from the Zulu kingdom to reconstitute family structures in Natal, arguing that the male-centric refugee regulations posed considerable difficulties in this process.37

Carolyn Hamilton’s book on Shaka and the “limits of historical invention” throws new light on the late precolonial and colonial histories of Natal and Zululand.38 Hamilton argues that white observers circulated both positive and negative stories about Shaka, drawing in both cases on indigenous discourses that offered contrasting accounts of Shaka’s rule as a source of order or a source of chaos. In order to demonstrate Shepstone’s reliance on various images of Shaka as models for his native administration, Hamilton discusses Shepstone’s research on “the historical grounds for African land claims in Natal.”39 Drawing on Wright’s doctoral dissertation,40 she contends that the two pieces produced by Shepstone in 1863–64 and published in the appendix to the Cape Native Laws Commission report relied on testimony given by about fourteen oral informants.41 These are apparently the memoranda that Welsh mentions, and one must be the source to which Atkins’s citation obliquely makes reference. Shepstone, according to Hamilton, used the Zulu discourses on order under the firm rule of Shaka, in contrast to Natalian chaos, as a justification for his own autocratic methods; in Shepstone’s usage, the geographic stereotype was reversed to assert order in the colony as contrasted with chaos in the Zulu kingdom. More important for present purposes, the Shepstone memoranda justified the indigeneity of Natal’s African population, though it consigned them to the less favorable land—the land that was to become locations. Shepstone put it as follows:

When the Boers arrived in what is now Natal in 1838, all the broken and bushy country, as well as all the forest country, was, as a rule, occupied by natives . . . and all the open country not; this was the natural result of the political condition of the inhabitants with regard to the Zulus; under such circumstances it will be obvious, that it is impossible to name all the localities occupied by different tribes, or to decide that any one locality was the only spot which any one Tribe occupied.42

So, in Shepstone’s view, most of the “tribes” living in colonial Natal had aboriginal rights to be there—but not to any particular piece of land and certainly not to the better-watered and richer-soiled agricultural land that lay along the road from Durban to the interior. More important, the scattered nature of aboriginal occupation of what became Natal precluded African claims against white, or state, ownership. In other words, his analysis, though careful and partially based on oral testimony, is a useful reflection of the ambiguity colonial authorities felt about the African populations in their midst and on their borders. He seems to be saying that these people are ours, we need them, and they have a long-standing right to be here, but they must now be present in a way that is useful to us, not disruptive of or threatening to our productive use and enjoyment of this land.

This brings me back to Welsh. Despite the fundamental ahistoricism of his argument that the Shepstone methods of native administration in Natal constituted the “roots of segregation” in the vastly different circumstances of twentieth-century South Africa,43 Welsh is on to a critical issue. As he puts it, “The belief that the large majority of Africans in Natal were ‘refugees’ with no legitimate claim to land rights profoundly affected the final land settlement, and, indeed, became an important element in the colonists’ ‘social charter.’”44 Mahmood Mamdani raises a similar concern in analyzing the way that ascribed indigeneity was a necessary condition of full citizenship in postcolonial Central Africa and became a concept with murderous results.45 The irony, of course, is that in a colonial situation, it was only English- and Dutch-speaking whites—immigrants and descendants of immigrants—who were entitled to full citizenship. However, the idea that most Africans in the colony were also recent arrivals enabled settlers and officials to fantasize that they had arrived in an empty land. Shepstone was more pragmatic as well as somewhat more protective of the Africans he hoped to civilize. He therefore marshaled evidence of indigeneity, even while being careful to assert that it did not invalidate any white claims to land. His proposal to remove up to half of Natal’s African population was not directed at any particular subgroup of Africans resident in Natal. The eagerness with which the settler-dominated commission of 1852–53 latched on to this proposal, however, again reflected the widespread white belief that blacks in the colony were interlopers, there primarily to serve white masters. This was unfortunately a belief that reappeared in the mid-twentieth century, under the direction of a powerful white supremacist state that possessed at least temporary power to deliver “surplus” people “back” to the areas from which they were deemed to have strayed.46

The evidence suggests that there may well have been a large rise in the African population of the territory in the early years of white settlement, due to a variety of causes. First, a significant number of people crossed into Natal during the Zulu kingdom’s “breaking of the rope.” Second, others continued to cross the river as “refugees,” spurred no doubt by a variety of economic, affective, and political motives.47 And with the threat of raiding and tribute collection erased within the colonized territory, people no doubt took up residence in more open areas, where their presence was more noticeable to white officials. In addition, much of the idea of “vacant” land in African colonial history rests on white misunderstanding—however willful—about African sovereignty and land use. Land that appeared empty from an exclusive title or commercial farming point of view often consisted of fallow fields connected to a community’s long rotation through shifting cultivation or grazing land that was being used seasonally through transhumance practices.48 Ironically, later white cattle farmers adopted the practice of seasonally moving cattle between higher and lower elevations in Natal, giving much of their land an appearance of emptiness, and large amounts of white-owned farmland remained underused for decades.49

Much of the perception of a black population increase probably amounted to a slow dawning on white officials of the real nature of the situation into which they had plunged—ruling a large and fragmented African population while catering to the perceived needs of a small but vocal white population. White settlers and colonial administrators felt a rising anxiety in the face of a large and apparently growing population of Africans whose political organization, land use patterns, and relationship to powerful African neighbors were largely mysterious. Would a thinly populated white colony be able to monopolize land and political power in the face of a rapidly growing black population, with many of these people apparently returning to a region from which they had recently departed? Would a thin administrative presence be able to render the colonized population “legible” to the state for purposes of implementing taxation and indirect rule?50 As Donald Moore paraphrases Marx and Engels in reference to Zimbabwe, a spectre was haunting Natal, “the spectre of racialized dispossession.”51 That spectre triggered recurring anxiety about the presence, and number, of black inhabitants of the colony.

Drawing borders—creating new maps on top of old ones—has the effect of redefining rights of inclusion and exclusion. I was somewhat shocked several years ago when an otherwise progressive South African woman giving a presentation at the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) argued that many of postapartheid South Africa’s ills could be attributed to a spiraling influx of illegal aliens. While we in the audience listened politely, it was all but certain that undocumented foreign nationals were trimming hedges and blowing leaves within a short distance of where we sat.

This was my first introduction to South Africa’s postapartheid politics of indigeneity. That political development, though unfortunate, is hardly surprising in a country with astronomical unemployment and searing poverty that is nevertheless relatively wealthy by contrast to its neighbors. Hawkers from Mozambique, Congo, and Zimbabwe crowd Johannesburg’s pavements while upscale immigrants from Nigeria and beyond compete for professional positions. At the same time, the politics of “black empowerment” enable the rapid economic rise of a select few, leading to a more equitable distribution of wealth across racial boundaries at the higher end of the scale, even as the poor and hopeless remain disproportionately black. Middle-class whites, the beneficiaries of apartheid’s distributive mechanisms, continue to prosper but argue that they are no longer considered truly South African under the new dispensation. A racial politics of indigeneity has developed, with some people asserting rights based on “first people” status, others arguing for blackness as the marker of belonging, and some whites still cling to notions of objectively defined merit while conveniently ignoring the sordid histories that delivered their superior levels of education.52

Jean and John Comaroff called attention to South Africa’s new politics of indigeneity in an article on the controversy over “alien” and “invasive” plant species in the Cape.53 They argued that the rhetoric deployed in relation to the problem of alien species in a fragile ecosystem merges seamlessly into the rhetoric of national rights and exclusivity raised against the makwerekwere—the neologism for African foreigners, especially undocumented ones—in South Africa.54 There is some poetic justice in the rise of nativity as a supreme value in a land formerly ruled through a racial hierarchy that placed white immigrants and their descendants at the pinnacle. Nevertheless, there are disturbing aspects of this trend. Mahmood Mamdani has argued persuasively that the genocidal politics of recent Central African history grows out of understanding some people as indigenous and hence first-class citizens and others as latecomers and hence second-class pseudocitizens.55 Similar issues have arisen in various parts of the continent, often with tragic results.56

Mamdani’s compelling argument, combined with the Comaroffs’ discussion of the rhetoric of nationhood in South Africa, helps point to the importance of this aspect of early colonial history in Natal. A finding of indigeneity or its absence was the key to the colony’s attitude toward its subjects, though no degree of indigeneity would trump the superior racial claims of whites. The officials of this young colonial state were faced with an apparently growing and clearly alien subject population. They were surrounded by independent African states with the capacity to resist imperial aggression and, it was feared, to threaten colonial security. The colony at this stage lacked the means to render its subject population legible through such measures as census taking and regulation of marriage practices, practices it was only to initiate in 1869.57 Its officials found themselves befuddled by the recent and disorderly historical movements of their new subjects. As a result, the colony sought to define them—or at least a preponderance of them—as outsiders with limited rights to the land or to the protection of the government. Shepstone, whose protective urges were driven by the fear of revolt and balanced by his urge to legitimate exploitation, used African testimony to conclude that even those African communities that had considerable ties to the land could not claim any particular parcel of land. As a result, Africans could not interfere with the broad civilizing project of early Victorian colonialism, which focused on taming and transforming the land to make it commercially productive, even if Africans’ own transformation was not yet its direct object.

1. Philip Curtin, The Rise and Fall of the Plantation Complex: Essays in Atlantic History, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 14–15.

2. John Lambert, Betrayed Trust: Africans and the State in Colonial Natal (Scottsville, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 1995).

3. John Bird, The Annals of Natal, 1495–1845 (1888; repr., Cape Town: C. Struik, 1965), 2:165–68, 299–300, 465–66. These boundaries corresponded roughly to the area the Zulu kingdom had ceded to the Boer settlers in 1839.

4. Ibid., 1:536–40.

5. Dan Wylie, Savage Delight: White Myths of Shaka (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 2000), 91–94; Charles Rawden Maclean, The Natal Papers of “John Ross”: Loss of the Brig “Mary” at Natal with Early Recollections of That Settlement and among the Caffres, ed. Stephen Gray (Durban, South Africa: Killie Campbell Africana Library, 1992), 153.

6. See, e.g., Bird, Annals of Natal, 1:624–25, 635–39; Keletso Atkins, The Moon Is Dead! Give Us Our Money! The Cultural Origins of an African Work Ethic in Natal, South Africa, 1843–1900 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1993), 16.

7. Bird, Annals of Natal, 644–45. It is notable that the resolution in support of this plan claimed that most “Kaffirs” then in Natal (in 1842) were from elsewhere and “had no right or claim to any part of the country, they having only come amongst us after the emigrants had come hither, with a view of being protected by us.”

8. Testimony of Henry Cloete, Recorder, to Native Affairs Commission, 3 November 1852 (emphasis added); see also testimony of Rev. Louis Grout in the same file, SNA 2/1/2, Pietermaritzburg Archives Repository (hereafter cited as PAR).

9. Natal Native Affairs Commission, 1852–53, 41, PAR; Thomas McClendon, “The Man Who Would Be Inkosi: Civilising Missions in Shepstone’s Early Career,” Journal of Southern African Studies 30, no. 2 (2004): 251–70.

10. Charles Ballard, “Traders, Trekkers and Colonists,” in Natal and Zululand from Earliest Times to 1910: A New History, ed. Andrew Duminy and Bill Guest (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 1989), 126.

11. McClendon, “Man Who Would Be Inkosi.”

12. Edgar Brookes and Colin de B. Webb, A History of Natal (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 1965), 37–38, 45–46; McClendon, “Man Who Would Be Inkosi.”

13. Brookes and Webb, History of Natal, 47–50.

14. Ibid., 50.

15. George McCall Theal, History of South Africa, vol. 3, 3rd ed. (London: Allen and Unwin, 1916), 229.

16. Brookes and Webb, History of Natal, 52, 59, 65, 69–70. Much of this reiterates evidence and conclusions given in Edgar Brookes and N. Hurvitz, The Native Reserves of Natal (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1957), 1–4.

17. David Welsh, The Roots of Segregation: Native Policy in Natal, 1845–1910 (Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1971), 2–5.

18. Ibid., 2, citing Bird, Annals of Natal, 2:311.

19. Welsh, Roots of Segregation, 2.

20. Ibid., 3–4.

21. John Wright, “Political Mythology and the Making of Natal’s Mfecane,” Canadian Journal of African Studies 23, no. 2 (1989): 272–91.

22. Norman Etherington, The Great Treks: The Transformation of Southern Africa, 1815–1854 (New York: Pearson Longman, 2001), 329–49. For a useful collection of interventions into the Mfecane debates, see Carolyn Hamilton, ed., The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 1995).

23. In another piece, Etherington has suggested that the idea of empty land in the southern African interior resulted from poor mapping practices in the early nineteenth century. Norman Etherington, “A False Emptiness: How Historians May Have Been Misled by Early Nineteenth Century Maps of Southern Africa,” Imago Mundi 56, no. 1 (2004): 67–86. My thanks to Karl Ittmann for bringing this piece to my attention.

24. On large states, see Etherington, Great Treks, 31–35. For Zulu power in Natal, see Wright, “Political Mythology.”

25. Timothy Keegan, Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order (Cape Town: David Philip, 1996), 343n15.

26. Julian Cobbing, “The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo,” Journal of African History 29, no. 3 (1988): 487–519. In fact, the source Cobbing cites, at 509–10n111, suggests that not only what became Natal but also in fact the entire territory from Pondoland (south of Natal) to Delagoa Bay had been “conquered and laid waste” by the Zulu king Shaka. George Thompson, Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa, vol. 2, ed. Vernon S. Forbes (1827; repr., Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1968), 249.

27. Clifton Crais, “The Vacant Land: The Mythology of British Expansion in the Eastern Cape, South Africa,” Journal of Social History 25, no. 2 (1991): 256. Archaeological evidence shows that farming communities were well distributed in South Africa, including the area that became Natal, from the first millennium CE. Peter Mitchell and Gavin Whitelaw, “The Archaeology of Southernmost Africa from c. 2000 BP to the Early 1800s: A Review of Recent Research,” Journal of African History 46, no. 2 (2005): 209–41. Nevertheless, I have heard the old myth repeated by a well-educated and politically liberal white South African as recently as 2006.

28. W. J. de Kock, History of South Africa (Pretoria: Government Printer for the Department of Information, 1971), 11. My thanks to Dennis Cordell for providing this quote.

29. Crais, “The Vacant Land,” 266–67.

30. Ibid., 266.

31. Dan Wylie, “‘Proprietor of Natal:’ Henry Francis Fynn and the Mythography of Shaka,” History in Africa 22 (1995): 414; cf. Bird, Annals of Natal, 1:73–76 (paper written by Fynn between 1834 and 1838, in which Fynn calls Natal “totally depopulated”), and Bird, Annals of Natal, 1:103. Shepstone, by contrast, argues in an 1875 paper that although “wave after wave of desolation” had “swept over the land,” the region was not depopulated. Rather, “many thousands” remained but were reduced to a “hopeless and wretched” condition. Bird, Annals of Natal, 1:158–59.

32. Wylie, “‘Proprietor of Natal’”; Etherington, “False Emptiness.”

33. Atkins, The Moon Is Dead! 9–13. The critique of the devastation theory is made at 147n3.

34. Ibid., 13.

35. Ibid., 17–22.

36. Ibid., 22.

37. Ibid., 18–54.

38. Carolyn Hamilton, Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

39. Ibid., 90.

40. John B. Wright, “The Dynamics of Power and Conflict in the Thukela-Mzimkhulu Region in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries: A Critical Reconstruction” (PhD diss., University of the Witwatersrand, 1989).

41. Cape of Good Hope, Report and Proceedings of the Government Commission on Native Laws and Customs, 1883, pts. 1 and 2 (Shannon: Irish University Press, 1970), 415–26.

42. Theophilus Shepstone, “Historic Sketch of the Tribes Anciently Inhabiting the Colony of Natal, as at Present Bounded, and Zululand,” 1864, Report of Select Committee (7 November 1862) on Granting Natives Documentary Tribal Titles to Land, in Colenso Papers A204, v. 144, c. 1280/9, PAR.

43. I am grateful to John Wright for alerting me to the ahistoricism in Welsh’s argument.

44. Welsh, Roots of Segregation, 2–3.

45. Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism and the Genocide in Rwanda (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002).

46. Surplus People Project, Forced Removals in South Africa: The Surplus People Project Report, vols. 1–5 (Cape Town: Surplus People Project, 1983).

47. Although contemporary officials tended to stress political motivations, Atkins, in The Moon Is Dead!, emphasizes the role of affective motivations such as marriage and the reconstitution of families.

48. See, e.g., Donald S. Moore, Suffering for Territory: Race, Place and Power in Zimbabwe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 166–68; Robin Palmer and Neil Parsons, eds., The Roots of Rural Poverty in Central and Southern Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 6–8.

49. Thomas V. McClendon, Genders and Generations Apart: Labor Tenants and Customary Law in Segregation-Era South Africa, 1920s to 1940s (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2002), 24; Moore, Suffering for Territory, 131; Palmer and Parsons, Roots of Rural Poverty, 7–9.

50. For legibility, see James Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999).

51. Moore, Suffering for Territory, ix.

52. See the discussion of immigration and a new South African identity in Lauren B. Landau, “Transplants and Transients: Idioms of Belonging and Dislocation in Inner-City Johannesburg,” African Studies Review 49, no. 2 (September 2006): 125–45.

53. Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff, “Naturing the Nation: Aliens, Apocalypse and the Postcolonial State,” Journal of Southern African Studies 27, no. 3 (2001): 627–51. Other pieces discussing xenophobia and nationalism in southern Africa include: Gerhard Mare, “Race, Nation, Democracy: Questioning Patriotism in the New South Africa,” Social Research 72, no. 3 (2005): 501–30; Francis B. Nyamnjoh, “Local Attitudes towards Citizenship and Foreigners in Botswana: An Appraisal of Recent Press Stories,” Journal of Southern African Studies 28, no. 4 (2002): 755–75; and Jonathan Crush and David A. McDonald, eds., “Special Issue: Transnationalism, African Immigration and New Migrant Spaces in South Africa,” Canadian Journal of African Studies 34, no. 1 (2000). A recent news item suggests that in Nigeria, people often suffer discrimination on the basis of being “foreign” to a given region within the country. Alex Last, “Nigeria Discrimination Condemned,” BBC News, 25 April 2006, available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4943700.stm, accessed 25 April 2006.

54. The term is said to be based on what foreigners’ speech patterns sound like to South African ears. Gerhard Mare, “Race, Nation, Democracy,” 507 and 507n1. See also Phaswane Mpe, Welcome to Our Hillbrow (Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press, 2001).

55. Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers.

56. Peter Geschiere and Stephen Jackson, “Autochthony and the Crisis of Citizenship: Democratization, Decentralization, and the Politics of Belonging,” African Studies Review 49, no. 2 (September 2006): 1–14.

57. In 1869, the colony imposed regulations on marriage designed to raise new revenue while simultaneously limiting polygyny and protecting against forced marriage. Thomas McClendon, “Coercion and Conversation: African Voices in the Making of Customary Law in Natal,” in The Culture of Power in Southern Africa: Essays on State Formation and the Political Imagination, ed. Clifton Crais (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003), 49–63.