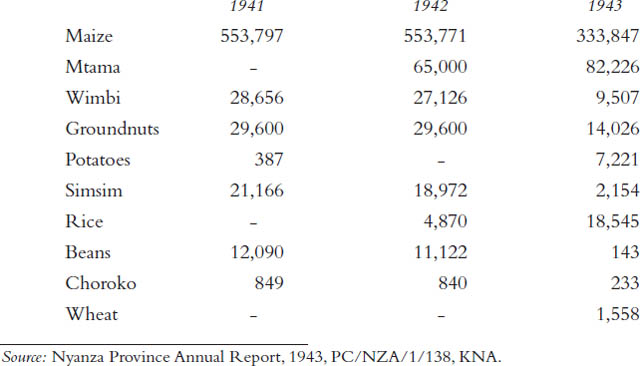

Table 6.1. Nyanza Province crop production, 1941–43 (in 200-pound bags)

When World War II broke out, colonial authorities in Kenya already had developed a plan to mobilize African labor for the military, and beyond that, they also had a military labor unit in place, just waiting to be given the green light to enter the war. That military unit was the Pioneer Corps. Due in large part to a pervasive colonial discourse that tended to regard Kenya, especially western Kenya, as a colony teeming with an inexhaustible supply of labor, the Pioneer Corps was created to channel African labor for military service in the war. But as the war began and African labor recruits started serving in the military, colonial assumptions about a teeming African population came under considerable strain. Labor shortages became common, and agricultural production declined in areas most affected by overzealous military recruitment. Colonial authorities realized that African labor in Kenya was not limitless after all. Complaints from conscientious colonial officials and African resistance forced them to review some of their assumptions. The limits of the Pioneer Corps led to a reassessment of some of the long-standing colonial views about African population and labor in colonial Kenya. It also demonstrated the need for colonial authorities to develop sound policies based on a concrete and realistic understanding of population dynamics in Kenya African societies.1

Colonial authorities started toying with ideas on how best to channel Kenya’s labor force into colonial development as soon as Kenya became a protectorate. Their objective when they took their posts in Kenya was to transform it into an independent entity capable of maintaining itself and paying for its own administration. They believed that an understanding of Kenya’s demographic characteristics would help them better plan for development and make the colony financially independent of the British government. Their major difficulty during those early years was that they did not have a very clear knowledge of the size of the population. Handicapped in this way, colonial authorities often resorted to rough estimates of Kenya’s population for planning purposes. Sir Gerald Portal was one of the first colonial administrators in East Africa to try to estimate the population of Kenya.2 In 1897, for instance, he put the population at 450,000.3 During the same year, A. H. Hardinge, the first commissioner and consul general for East Africa Protectorate, made a working guess of Kenya’s population as 2.5 million. This estimate was revised in 1902 to 4 million.4 The reason behind this dramatic rise in Kenya’s population was the redemarcation of the Kenya-Uganda boundary. The western boundary, which up to 1902 stood at Naivasha, was moved farther west to modern Busia, thus adding heavily populated sections of eastern Uganda to the Kenya Colony.

As Kenya gradually evolved into a full-fledged colony, colonial authorities continued to develop better census methods as they visualized ways in which the colony’s allegedly abundant population could be mobilized.5 In a bid to make the colony pay for itself, colonial authorities spent hours assiduously calculating the size, age, and distribution patterns of Kenya’s population. They commissioned studies on the colony’s demographic profile. Some of these studies, particularly those by administrators and anthropologists, concentrated on delineating the size of Kenya’s ethnic communities, together with their “habits” and traits.6 Others focused on projects, works, and activities within the various ethnic communities, essentially identifying how each could contribute to the colony’s development.

By the 1930s, colonial authorities had become adept at census exercises. A 1931 estimate put Kenya’s population size at 4.1 million, only 100,000 more than the population in 1902. This apparent stagnation in the population is puzzling. It may well be that the earlier estimates were not accurate, given that most of them were based on guesswork by colonial officials. However, scholars such as R. M. A. van Zwanenberg have argued that during the early twentieth century, East Africa’s population actually did decline. They have noted that this period was characterized by major challenges for East African people. The entire region was afflicted by wars. It was also plagued by diseases such as smallpox, dysentery, chicken pox, measles, poliomyelitis, plague, influenza, and whooping cough. Some of these diseases were old; others were just making “their appearance . . . by at least 1890.”7 Van Zwanenberg concludes that many people died.

This was a period of tumult, confusion, and uncertainty. World War I alone claimed more than 144,000 people in the region. Van Zwanenberg argues that, due to these challenges, “there seems to have been a downwards trend in the population from the 1890’s until the middle of the 1920’s.”8 Beginning in the 1920s, however, the region’s population, including that of Kenya, started recovering. Due in no small part to colonial medical programs to combat diseases, Kenya’s population started rising. By 1931, it had climbed to 4.1 million. In 1939, it stood at 4.8 million.9

Census methods continued to improve. By 1948, censuses were being conducted like “a military exercise.”10 And by this time, the population of Kenya was reportedly 5.7 million.11 Nyanza Province’s share of Kenya’s population throughout this period was believed to be substantial. The combined population of the Nyanza Province by 1940, including, at that time, the Nandi and the Kipsigis and some parts of the present-day western Kenya, was 1.25 million, or around one-quarter of the overall population by the beginning of the war.

When the war broke out, it was therefore not surprising to find that colonial authorities had anticipated—and laid down nearly complete plans for—the appropriation of the colony’s labor for military service. Fears that war would break out in Europe were already rampant in Kenya by early 1939. As Europe moved toward war, colonial authorities in Kenya started preparing. In a critical move, the chair of the Manpower Committee of the Kenya Colony circulated a communiqué soliciting suggestions on the formation of a “Labour Corps.” The communiqué tellingly suggested that Nyanza Province should provisionally contribute 3,000 men.12 If Kenya was perceived in colonial discourses as a large labor reserve, Nyanza Province in particular and western Kenya as a whole were the focus of that perception.13 Colonial administrators based in Nyanza further enhanced and solidified this view. S. H. Fazan, the provincial commissioner, often noted that Nyanza teemed with labor, concluding that the establishment of a military labor corps would not be a major problem for the province. Fazan described himself quite proudly as “a Provincial Commissioner of a Province with a million and a quarter natives which in the war of 1914–18 in East Africa bore the brunt of the military and civil labor requirements.”14 Fazan’s enthusiasm and energy then not only transformed Nyanza Province into a labor reserve but also made it into the main base for intensive labor recruitment.15 Although the letter from the Manpower Committee sought ways of recruiting African labor, it did not provide the actual mechanism by which this could be done. It left implementation to colonial officials on the ground.

The details of drawing manpower into the war fell to Fazan.16 The “personal request,” Fazan was to recall later in the war, was for him “to write a memorandum” on military labor service. He began by collecting suggestions from his district commissioners and recommending the formation of a military labor unit. While writing his recommendations, Fazan admitted that “the subject of Manpower . . . is constantly in [my] mind.”17 Even by the normal standard of colonial obsession with labor in Kenya, Fazan was unusual. In reports issued while serving as the provincial commissioner of Nyanza, he claimed that he could not avoid commenting about the military because the views of civil administrators were also crucial to the conduct of the war. He claimed that there had already been occasions “when the civil Administration has foreseen the needs of the military before they were declared, and consequently has been able to meet them, with more expedition and less disturbance than would otherwise have been the case.”18 The fact that the provinces were required to conduct large-scale recruitment “at short notice,” Fazan observed on another occasion, “demand[ed], in my submission, that we should overhaul our recruiting organization and have it ready in advance, at least on paper and also, to some extent in the field.”19

Fazan often argued that, through vigorous enforcement of existing laws, labor could easily be channeled into military service. He became quite influential within military circles, and the military saw him as an ally. The governor of the colony praised him for “zeal and enthusiasm.” Indeed, it is no wonder that Fazan later relinquished his post in Nyanza to become a liaison officer with the military. After collecting views and opinions of colonial officials, he recommended the establishment of a military labor unit. That unit came to be called, euphemistically, the Pioneer Corps.

There were several major difficulties in getting the unit off the ground. Although many scholars characterize Kenyan recruits as having generally been willing to serve in the Pioneers, the evidence suggests otherwise—indicating that recruits were very reluctant because it reminded them of the ill-fated “Carrier Corps of the First World War and everything connected with it.”20 Geoffrey Hodges has estimated that upwards of 100,000 African men died during military service in the Carrier Corps—or Kariokor (as it was known locally)—in East Africa during World War I. That was nearly 10 percent of the total number of men serving in British military forces in East Africa, and no compensation was given to soldiers or their families for injuries or death that occurred during the war. Service in the Carrier Corps was almost synonymous with misery and death. Thus, because of the horrible experience of askaris (soldiers, in Swahili) in World War I and in other colonial military expeditions, military labor units were feared and loathed. In the words of Fazan, men had “not forgotten that in the last war there were many unrecorded casualties and many gratuities owing to the dependants of deceased carriers were not paid.”21 The men knew “that the Carrier Corps was alternatively known as the Labor Corps and its head as the Director of Military Labor. Any mention of a Labor Corps [was] undoubtedly . . . associated in their minds with the carrying of loads and all the hardships of the last war, and they will not engage in it voluntarily.” Askaris disliked military service, especially units associated with labor. The word labor, as in the “East African Labor Unit” or in the “Labor Corps,” then, induced images of suffering, fear, and death.

These problems were additionally complicated because the men who served in the units were often not issued rifles. “The great complaint among the men, who are otherwise keen and proud of themselves,” Fazan revealed, “is that their women will mock them if they are not armed.”22 Without rifles, the Pioneers felt ordinary, as ordinary as the despised jo Apida (employees of Public Works Department). As mere jo leba (laborers) in the army, potential recruits felt that they would not be as respected as “real” soldiers serving in, say, the Kings African Rifles.23 Fazan came to realize that the word labor would impede the creation of a successful military labor unit, so he proposed that the word be removed from the name of the organization. Upon receiving the communiqué from the chair of the Manpower Committee proposing to establish a “labor corps,” Fazan recalled that he and his committee immediately “headed him off the term ‘Labor Corps’ and chose ‘Pioneer Corps’ as likely to be more popular.”24

The term Pioneer was well chosen. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Pioneers was first used in the eighteenth century to refer to “an advance party of soldiers” whose task in eighteenth-century Western armies was “clearing and making roads.” Although it accurately revealed the kinds of tasks that the proposed unit would perform, the term was deliberately opaque. It was chosen to lure askaris into the army by making them believe that they were part of a bigger plan; implicit in the term was a suggestion that the unit would be a forerunner to a successor formed during wartime.25 By adopting the term Pioneers and dropping more accurate, albeit frightening, labels such as labor, the administration was dishonest. The term was willfully misleading and took advantage of askaris without seriously addressing their fears. And though the name change enabled the government to lure unsuspecting men into providing labor, it did not, in reality, represent a qualitative change in the nature of African military service. Like its eighteenth-century precursor, the unit had a simple mission: providing labor—clearing and building roads, among other things. Askaris would not be happy when they discovered the true mission of the Pioneer Corps because the colonial administration had failed to reveal the nature of service or address the reasons why aksaris hated labor-intensive units.

Fazan’s proposal targeted certain ethnic communities. He believed that the best communities for enlistment into the Pioneer Corps were the “Kavirondo,26 the Kamba and Meru, and some of the coast tribes [sic].”27 His recommendations reflected the pervasive view in British colonial circles that some communities were “warlike” or “martial” and therefore well suited for service in combat units, whereas others were only good for labor units.28 Assessing the suitability of various African communities for military service, Fazan noted that in terms of quality “for a Pioneer Corps . . . the Kavirondo are certainly among the best of the tribes [sic].”29 And among the Kavirondo, Fazan proposed that the Luo should be targeted first because “the Luo, no doubt, would yield with a fairly good grace to conscription; the Bantu would come in not readily and there would probably be some degree of disaffection in some of the more political locations.”30 Fazan argued that the communities needed to be convinced to join the Pioneer Corps, for otherwise, “they will not engage in it voluntarily.”31 He argued that if “it was made clear” to these communities that “the Pioneer Corps will not carry loads as part of their regular duties and that they will in fact be auxiliary troops who would receive some training and at least some proportion of whom would be armed, they would come forward for that readily enough” (emphasis added).32 A pledge was also made to the men, assuring them that joining the Pioneers would “not spoil their chances of getting into the KAR [the King’s African Rifles].”33 Most of these promises were never kept; when it came to joining the KAR, the Pioneers were given first preference—but usually, only the men from “martial communities” graduated from the Pioneers into the KAR. Without doubt, deception was being used to recruit unsuspecting askaris into the Pioneer Corps.

Having analyzed and prepared his recommendation on the establishment of the Pioneers, Fazan submitted it to the chair of the Manpower Committee in March 1939. In this report, Fazan also suggested the formation of an auxiliary corps. The Manpower Committee accepted the idea of establishing a Pioneer Corps but took no action on the larger proposal to establish an auxiliary corps “until after war broke out . . . but the principle to form a nucleus of ‘Pioneer Corps’ was approved.”34 At a subsequent meeting, held on 14 and 15 April 1939, a resolution was adopted calling for a rudimentary nucleus of the Pioneer Corps. According to Fazan: “It was agreed that the Provincial Commissioner of Nyanza, after consultation with the Provincial Commissioner, Central, and the Director of Public Works, should furnish a draft scheme for the formation of a such [sic] nucleus to be expanded to 1,000 strong if money was obtained for strategic roads.”35

This meeting, moreover, came up with recommendations on specific steps to form a future Pioneer Corps. The first batch of the Pioneers was supposed to consist of a peacetime nucleus of 1,000 men, which in wartime would be expanded to a force consisting of thousands of men. Other provinces, such as Central Province, were also required to establish “peace time nuclei in similar proportion to the quota required from them in wartime.”36 A list of names of potential recruits was to be drawn up, but authorities realized in time that “if we make a provisional list of names and warn the persons listed we shall simply start a pack of rumors and nervousness all over the reserve. Whatever we may say everybody will think he is down for the carrier corps and many of the persons listed would immediately seek the shelter of other work as far away from the reserve as possible.”37 Officials knew that some men might quit the Pioneers after finding out they were being misled, and so the government devised ways of recruiting and holding the men without making them aware that they would be serving with the military labor corps during the war.

To keep the men busy as war neared without alerting them as to their true mission, the government secured a grant for the construction of roads in Nyanza. While recruiting the men under the guise of constructing roads, care was to be taken to ensure that the number of recruits was “sufficient to form a nucleus . . . and [that the men were] employed on a six months’ contract or longer and that all superior staff [foremen, gangers, nyaparas (supervisors), and so forth] employed on the work [would] be carefully selected with a view to their eventually becoming warrant officers and NCO’s.”38 Another recommendation was that the “gangs should at first be treated as ordinary road gangs in all outward respects although more care would be given to the supervision and weeding out of undesirables, but as the time approached when precautionary measures need no longer be concealed they would begin to receive some degree of drill and special training, various skilled ranks such as carpenters could be added and a proper Pioneer Corps [would] begin to take shape.”39 Given the need to keep the men ignorant of their future work, the Pioneer Corps was to be “developed as part of the Public Works Department [Apida] and with officers, foremen, and gangers largely drawn [from] it but . . . as development is advanced it should become independent of the Public Works Department and form a military auxiliary unit [such] as a Pioneer Corps (R.E.) [Royal Engineers].”40 Other officials were to do the same thing in their provinces, and train the recruits “for a period which might extend to two months after which they should be moved as required for roads or other works of military importance.”41

The budget submitted in Fazan’s memorandum of 25 April 1939—for a corps of 2,000 men working for two months in Nyanza (and other provinces), including pay and rations, equipment, construction materials, and consumable stores—came in at £10,963; it was later discovered that the estimate had omitted tentage.42 Once the Pioneers left Nyanza and were employed by the military, the monthly cost of the company—the recurrent expenditure—was estimated at £1,889. At a maximum strength of 10,000 men, a colony-wide Pioneer Corps would cost £53,800 to establish, plus recurrent expenditures. The financial secretary accepted these recommendations and budget figures and called for the expenditure of £2,000, pending “a grant from the imperial government.”43 The grant was subsequently increased from £2,000 to £2,350, to cover the working cost of maintaining the corps for two months. The initial grant available to Nyanza was estimated to be enough for the maintenance of a peacetime nucleus of “1 Assistant engineer, 2 European foremen, 1 Time keeper and clerk, 2 Asiatic Gangers, 3 Masons, 1 Carpenter, 1 Blacksmith, 2 African Sergeants, 10 Corporals, and 300 men.”44

Recruitment for the first unit began in late May 1939. In June, some 180 men presented themselves for service in the Pioneer Corps, but when they learned of the provisional terms of service, many quit and returned home. Out of the 180 men who initially joined the Pioneers, 110 went home and 70 remained.45 The low pay and long duration of service provoked the departure of most of the first recruits.46 But the government soldiered on looking for men. By the first week of June 1939, training began and the number of recruits in the Pioneers increased to 80.

There were other complaints. Some askaris suffered from an outbreak of typhoid fever, which afflicted the camp due to “bad water supply” and the rocky nature of the ground. These conditions had led to the building of shallow trench latrines, which allowed fly breeding. When 300 recruits who were going to join the Pioneers were rejected on medical grounds and turned over to the Public Works Department at a wage of Kshs. 16/- and Kshs. 4/- for posho (maize meal), on better terms than the Pioneers were offered, “the incident rankled.”47 Some recruits, such as Okumu Aulo and Oyaga Ogola, fled the Pioneer Corps camp, and an order was issued: “Mshike hawa watu wenye kutoroka katika Pioneer Corps, mlete hapa kwa mara moja” (Arrest these people who fled the Pioneer Corps, and bring them here at once).48 Other recruits complained about the lack of rifles. During recruitment drives, the men had been promised rifles, but they never received them. When they heard that they would not be issued rifles, many refused to enlist, and others, upon enlisting, demanded firearms. Some men even went on “strike” over the lack of rifles, and “a few malcontents were discharged.”49

After its formation, the Pioneer Corps camped about three and a half miles beyond Ahero on the projected new route between Kisumu and Muhoroni. The officer in charge of the camp was R. Southby, reportedly an ex-officer of the Yeomanry with extensive campaigning experience.50 Things at the camp generally seemed to be running as planned by the government. A telegram from camp officials to Nairobi reported, for example: “60 recruits expected tomorrow and full strength will be reached very shortly. Recruiting now working smoothly. . . . Men responding excellently to drill and discipline and showing pride in corps.”51 During their time with the Pioneers at the Ahero camp, the recruits constructed 18.5 miles of one road and shaped and hard-surfaced 3 miles of another. By the time they finished constructing the Ahero-Muhoroni road, the Pioneers had shortened “the distance of the Kisumu-Muhoroni section of the main road to Nairobi from 54 miles to 37 miles, besides cutting out many awkward bends and drifts.”52

But it was soon discovered that Pioneers were spending too much time on extraneous activities such as road building, which took them away from their primary duty of training for military service in the corps. The training level of the unit at Ahero camp was found wanting. When an untrained detachment was sent to Nairobi for urgent duty in the first few days of the war, it was “not very satisfactory and returned crestfallen for further training.”53 In terms of technical skills, the corps was classified as unskilled, but there was a “fair sprinkling of technicians in its ranks and (some) can look forward to becoming semi-skilled.”54 In the latter half of October 1939, 125 Pioneers were chosen for deployment into the Royal Engineers (RE). This was a loss to the Pioneers, but those who left were “replaced by new recruits . . . [who] are equally good material.”55 As the recruits gradually adjusted to their mission in the Pioneers, they were issued safari shirts, belts and buckles, shorts, macduff shirts, caps, belt webbing coils with buckles, water bottles (charguls), haversacks, blankets, “messing utensils,” kit bags, and sandals, locally manufactured at Nakuru Tannery. To retain their service, members of the EAMLS (East African Military Labor Service) were promised that whenever KAR recruiters visited the province on recruitment exercise, the KAR would give the Pioneers first preference, taking “likely men from the Pioneer Corps before proceeding to recruit elsewhere in the districts.”56 Thus, besides serving as the nucleus for a future unit, the Pioneer Corps also served as a source of recruits for other military units.

The Pioneer Corps put the colony on a war footing, in addition to getting some roads constructed. It placed men at the ready for war instead of waiting to recruit them hurriedly in case of an emergency. By the time war broke out, these men were expected to “have some degree of training in advance together with their N.C.O.’s and Warrant Officers.”57 Recruitment into the corps was facilitated by older members of the Pioneers, who visited rural homes looking for recruits. When the war broke out, for instance, a party of sixty Pioneers was sent out to various parts of Nyanza to recruit men for the army. The number of recruits steadily increased at the camp, reaching 350 by 31 July 1939, where it remained until further orders were issued.

As the military situation in Europe deteriorated, an order was sent on 24 August 1939 to reorganize and streamline the Pioneers. European officers selected for military service whom the Manpower Committee had already alerted arrived at the camp for duty. Some of these officers were later released for urgent civil work, but others went on to lead newly formed battalions of the Pioneers. The First Battalion was led by Major C. C. Dawson Currie and the Second Battalion by Major E. H. Tapson. The acting and founding officer of the Ahero Depot, Major R. Southby, retired before the end of September 1939. His place was taken up by Captain W. Truro Norris, who became the new officer in charge of the depot.

The order for reorganizing and restructuring the Pioneers also saw the expansion of the corps because it called for the recruitment of more men in preparation for the war. Most of these recruits were already in service and were “by this time becom[ing] used to the Corps and the conditions of service.”58 Two days after the call for men, on 26 August 1939, Major Tapson of the Second Battalion went out on a recruitment drive. Many Kenyans heeded the call for recruits and “join[ed] in large numbers.” According to S. H. Fazan, “Volunteers had already begun to arrive in numbers.”59 By the time recruitment was suspended on 6 September 1939, the number in the Pioneer Corps stood at 1,900, and Fazan remarked that “the response of the natives [had] been truly amazing.”60 Most of these recruits came from Nyanza Province. This was in line with the first memorandum of the chair of the Manpower Committee, which had stated that Nyanza should “provide as many as 3,000 men” to the unit.61 And so, by November 1939, the two battalions created by the orders of the War Office consisted almost “exclusively” of recruits from Nyanza Province.62 Colonel Michael Blundell’s First East African Pioneer Battalion, for example, was “98% Nyanza” and predominantly made up of the Luo.63 “[The first] Rifles Engineers Company formed in Kenya and the two Pioneer Battalions wholly, in respect of their African ranks, were from Nyanza natives.”64 Blundell, whose battalion served in the Northern Frontier District and in Abyssinia, later observed in his memoir that it was composed of “men . . . [who] had all been recruited in Nyanza Province by the Provincial Commissioner.”65 Lieutenant Colonel W. H. A. Bishop wrote a letter to Fazan and thanked him “for all the trouble you have expended on these units from the outset.”66 When Italian aircraft bombed the Pioneers at Abu Haggag in 1942, Captain H. E. Humphrey-Moore, the commanding officer of 1808 Company, also underscored the origins of his troops: “Bar 40, the rest [280] of the company come from Nyanza Province.”67

The evolution of the Pioneer Corps reached an important stage when it was officially designated by the military as a combat unit and its askaris as combatants toward the end of 1939. On 11 November 1939, the newly classified combatants of the Pioneers left Nyanza for what Fazan described as “a more active field.” Their departure, he would later confess, made him “feel lonely without them.”68 Two days later, a company of the Second Battalion left. Finally, on 29 November, the remainder of the two battalions departed and were now “somewhere in Kenya, taking with them the good wishes of the provinces.”69

Among the Luo of Nyanza, the Pioneer Corps was known simply as Panyako, a corruption of the name Pioneer Corps. It was envisaged as a better replacement for the earlier, unpopular military unit, the Carrier Corps, or Kariokor.70 But all that buildup proved to be deceptive. The promises made to recruits when the corp was created—even its very name—simply skirted around people’s reluctance to serve in labor units, without dealing with their grievances. To be sure, the unit enabled the government to take advantage of the supposedly abundant labor of Nyanza in particular and Kenya in general during World War II. But the government lied. The East African Standard and the Nakuru Weekly News, for instance, noted in their editorial analyses that “the Pioneers were misled as to their terms of service.”71

The emergence of the Pioneers grew out of colonial assumptions about the inexhaustibility of the labor supply in western Kenya, yet it also demonstrated the limits of those assumptions. As the colonial administration established the Pioneer Corps and recruited men from western Kenya for the war effort, it contributed to severe labor shortages that affected food production. Africans and even some colonial officials complained about the ruthless conscription of men into the Pioneers and other colonial military units without regard to the impact on local societies. By the end of 1940, the provincial commissioner of Nyanza estimated that 82,820 Nyanza inhabitants worked for the military, government, and private European concerns. He observed in 1940 that “the provision of men for the army has been the most marked of our war contributions.”72 The number of men from Nyanza in the army and civil work climbed to 93,212 by the end of 1941; at that point, the number of Nyanza men in the army alone stood at “more than twenty thousand.”73 By January 1942, one document showed that there were 19,620 men from Nyanza in the army and 98,700 in various other labor services in the colony. Thus, more than 118,320 men from Nyanza worked for the military and the government. The contribution of the province to the military and particularly to the Pioneer Corps was very large.

To a substantial extent, this was due to the long-standing colonial views with regard to Nyanza Province and to the campaigns of Fazan himself, who often explained how labor in Nyanza and the colony as a whole could be mobilized and conveyed into military and civil duty.74 Indeed, during the early days of the Pioneers, he boasted that “Nyanza Province is quite capable of raising and training 5 Pioneer Battalions and also of recruiting drafts for five Auxiliary Transport Battalions.”75 To justify the channeling of western Kenya’s labor into the military, Fazan claimed during the early years of the war that Nyanza’s population was actually higher than commonly thought—“almost exactly 40% that of Kenya.”76 When it was estimated in mid-1941 that, in spite of the alleged abundant labor in Nyanza, only .5 percent of the province’s population was away on military and civil duty, Fazan proposed that the labor supply from Nyanza Province be increased to 1.5 percent because “it would have no adverse effects on the supply of labor for essential industry.”77 By 1942, the number of Nyanza recruits in the army had climbed to “nearly 30,000 men . . . and further [to] approximately 110,000 in civil employment outside of the reserve.”78 Thus, only 262,000 adult males remained in the reserves, and of them, even the colonial officials admitted, 60,274 were “totally ineffective by reason of ill-health and disablement, and the remainder are capable of agriculture.”79 By the end of 1942, the existing intensive policy of recruitment of men from Nyanza Province was therefore creating uneasiness among some colonial officials.80

These officials produced reports suggesting that recruits from Nyanza made up the majority of those men serving with the army. Thus, a district officer in Central Kavirondo District observed that most of the recruits in the army were from Nyanza.81 The district commissioner of Kisumu-Londiani believed that the number of Nyanza recruits “employed by the military is in excess of [the Nyanza provincial commissioner’s] estimates,” and he went to the extent of suggesting that an “expert statistician” should be hired to help calculate the number of Nyanza recruits in the army.82 Many of these men were recruited through conscription—a policy that began in 1942.83 Conscription was quite unpopular, but it was one of the ways by which the administration tried to make up for labor shortages in military labor units such as the East African Military Service Corps and the Pioneer Corps. By 1943, excessive recruitment began to have an effect on the province. Local administrators, among them D. Storr-Fox, the district commissioner of South Kavirondo, complained about the large outflow of recruits from Nyanza into the army and various civilian projects, which he believed affected food production. The district commissioners of Central and North Kavirondo even petitioned the government for a pause in conscription in February 1943, requesting that “in the interests of increased production . . . [the government should] arrange a respite of one month during February so that there may be concerted effort on cultivation.”84 This, they argued, would augment the “number of men who would be thus home during that month to help plant up.”85

A village elder from Alego, Siaya District, complained about overrecruitment and the exploitation of labor by the government in his home area. Expressing his objections with diplomatic metaphor, he said, “If an elephant is killed, everyone sets to the flesh with their knives, and the supply of meat seems inexhaustible. Nevertheless, there comes a time when the bones though not yet laid bare at last begin to appear.”86

Frustrated by the extent of government exploitation of labor in Nyanza, Storrs-Fox, the district commissioner of South Kavirondo, asked the authorities to relieve him of his duties in the civil service or transfer him elsewhere. Accusing the government of establishing a system that was taking advantage of the “poor and weak people for the benefit of those who consider themselves to be ‘Herrenvolk’ or ‘master race,’”87 he asked his superiors to “be so kind as to consider relieving me of my present appointment as District Commissioner, South Kavirondo”; he added that should the government “decide not to dispense with my services altogether, I would be willing and glad to continue to serve in any district or colony and in any capacity where I might be required.”88

The problems, brought about by excessive recruitment of labor from Nyanza, were exacerbated by drought, leading to a fall in food production in the early 1940s.89 Colonial reports for the period 1941 to 1943 show a considerable decline in the yields of food crops from Nyanza Province because of the lack of labor and rain (see table 6.1). Only rice and potatoes recorded significant increases.

When the government realized that agricultural production was dropping in Nyanza, it tried to ameliorate the problem by changing the recruitment policies that had created the Pioneers. For example, although the colonial military had earlier used a policy of ethnic-based recruitment, with each military unit recruiting from particular communities, this policy had changed by 1942. A policy of “tribal mixing” brought men from different ethnic communities together in the same military units—“martial” and “nonmartial” peoples working together.90 Colonel A. J. Knott argued that the new policy came into being because the military had realized that “a particular tribal failing is less likely to manifest itself in a mixed unit.”91 In reality, this new policy appears to have been occasioned at least in part by the emerging awareness within the colonial administration of the negative impact of overrecruitment in areas previously designated as “teeming” with inexhaustible supplies of labor. It gradually dawned on the administration that overrecruitment for military units such as the Pioneer Corps in western Kenya and other areas took labor away from food production and led to food shortages. By “mixing” men in military units irrespective of their ethnicity, the colonial authorities hoped to give these exhausted areas a chance to recover, as they targeted other regions to make up for any shortfall in recruitment.

Thus, the creation of the Pioneer Corps shows how demography influenced colonial policy in Kenya. It further demonstrates the limits of those policies. Western Kenya, in particular, was viewed as the source of an inexhaustible supply of labor. This perception led to the formation of the Pioneer Corps during World War II. But as men were enlisted by the government into the Pioneers and other military units, their departure led to labor shortages in agriculture. Famine became common. There were protests even among the colonial officials themselves over the excessive exploitation of African labor in western Kenya. The government was forced to address these problems by changing some of its policies and by reexamining some of its demographic assumptions. These assumptions about demography in western Kenya were tested to the limit by the creation of the Pioneers and other military units. In the end, the government was left with no alternative but to readjust its assumptions to meet the realities of wartime colonial Kenya.

1. As important as it is, the history of the Pioneer Corps and its connection to Kenya’s demographic and colonial labor policies has not been fully told, with the exception of memoirs such as that of Michael Blundell, a commander of a battalion of the First Pioneer Company. See Blundell, A Love Affair with the Sun: A Memoir of Seventy Years in Kenya (Nairobi: Kenway Publications, 1994). Blundell’s memoir is limited in scope in the sense that it is based solely on his own experiences as a European military officer whose level of interaction with the ordinary soldiers was circumscribed by military regulations and seriously limited by the racial hierarchy in colonial Kenya. Geoffrey Hodge’s work, The Carrier Corps: Military Labor in the East African Campaigns, 1914–1918 (New York: Greenwood, 1986), comes the closest to comprehending African military units and labor policies, but it deals with World War I. For British colonial Africa and labor exploitation for military service in general, see David Killingray, “Labour Exploitation for Military Campaigns in British Colonial Africa, 1870–1945,” Journal of Contemporary History 24, no. 3 (July 1989): 483–501.

2. Sir Gerald Herbet Portal was an administrator in East Africa between 1892 and 1893.

3. R. M. A. van Zwanenberg, with Anne King, An Economic History of Kenya and Uganda (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1975), 7.

4. Ibid. In this revised estimate, Uganda’s population was given as 3.5 million.

5. Kenya was known as the East Africa Protectorate between 1895 and 1920. As the protectorate expanded and its administrative structures developed, it was declared a Crown Colony and renamed Kenya in 1920.

6. Many of these publications are well summarized in B. A. Ogot, “History, Anthropology and Social Change: The Kenya Case,” in The Challenges of History and Leadership in Africa: The Essays in Honor of Betthwell Allan Ogot, ed. Toyin Falola and Atieno Odhiambo (Trenton, NJ: African World Press, 2002): 511–23. See also Charles W. Hobley, “British East Africa: Kikuyu Customs and Beliefs—Thahu and Its Connection to Circumcision Rites,” Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 40 (July–December 1910): 428–52; Charles W. Hobely, Bantu Beliefs and Magic (London: Frank Cass, 1967); G. St. J. Orde Browne, The Vanishing Tribes of Kenya (London: Seeley, Service, 1925); G. W. B. Huntingford, “Miscellaneous Records Relating to the Nandi and Kony Tribes,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 57 (July–December 1927): 417–61; and J. A. Massam, The Cliff Dwellers of Kenya (London: Frank Cass, 1968).

7. Van Zwanenberg, Economic History of Kenya and Uganda, 9.

8. Ibid., 10.

9. Ibid., 12. Van Zwanenberg and King project Kenya’s population backward to conclude that the population was 3.7 million in 1921, 4.1 million in 1931, and 4.8 million in 1939.

10. Ibid., 14.

11. The census of 1948 pegged Kenya’s population at 5.7 million. See van Zwanenberg, Economic History of Kenya and Uganda, 12, and F. F. Ojany and R. B. Ogendo, Kenya: A Study in Physical and Human Geography (Nairobi: Longman Kenya, 1973), 110.

12. S. H. Fazan, Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, to the Chairman of Man Power Committee, letter, 21 March 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, Kenya National Archives, Nairobi, hereafter cited as KNA.

13. See, for example, Ojany and Ogendo, Kenya; Anthony Clayton and Donald C. Savage, Government and Labor in Kenya, 1895–1963 (London: Frank Cass, 1974); and van Zwanenberg, Economic History of Kenya and Uganda.

14. S. H. Fazan, “The Pioneers: A Memorandum,” 14 September 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA; Fazan, “A Memorandum on Military Recruitment, 5 May 1941,” Recruitment of Africans for the Military, PC/NZA/2/3/67, KNA. For more on Fazan’s career, see David Anderson, Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 143–45.

15. For more of this discourse, see Ojany and Ogendo, Kenya; Clayton and Savage, Government and Labor in Kenya; and van Zwanenberg, Economic History of Kenya and Uganda.

16. Even before he arrived in Nyanza Province, Fazan was prodigiously computing the demographic patterns of Central Province, where he served as a district officer during the 1930s; see van Zwanenberg, Economic History of Kenya and Uganda, 10.

17. Fazan, “Memorandum on Military Recruitment,” 31 May 1941, Recruitment of Africans for the Military, PC/NZA/2/3/67, KNA.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Geoffrey Hodges, Kariokor: Carrier Corps (Nairobi: Nairobi University Press, 1999).

21. Fazan, “The Pioneers: A Memorandum on Certain Points Outstanding, 25 September 1939,” The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

22. Ibid.

23. Oketch Oyugi Aton, who served with the King’s African Rifles from 1941 to 1964, interview by the author, 19 December 2000. He said during the interview that African men hated the labor units. This view was shared by many other interviewees.

24. Fazan, letter, 6 July 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

25. The word pioneer literally means “forerunner” or “precursor,” suggestive of the fact that the unit would be the nucleus of a bigger unit, which the administration intended to form during wartime. The name “Pioneer” was meant to help reduce the stigma associated with military labor units, which frustrated government efforts at enlisting men because it embarrassed and agitated those slated to serve or already serving in them. Removing the label “Labor” and replacing it with “Pioneer” also allowed the government to claim that the unit was different from earlier military labor units.

26. The origins and meaning of the term Kavirondo is complex. It appears to have been coined by Arab-Swahili traders who, during the nineteenth century, used it to refer to communities in western Kenya such as the Luo and Abaluhya but mainly the Luo.

27. Fazan, “East African Pioneer Corps: Memorandum on the Cost of Training a Nucleus in Peace Time,” The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

28. For more detailed analysis of this issue, see Timothy Parsons, The African Rank-and-File: Social Implications of Colonial Military Service in the King’s African Rifles, 1902–1964 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1999), esp. chap. 3.

29. Fazan, Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, memorandum entitled “Labor Corps,” The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

30. Ibid. These kinds of colonial stereotypes about African ethnic groups should not have been very surprising. In the colonial period, many stereotypes circulated about African peoples. A large number of these stereotypes, as already indicated in this essay, were supposedly based on colonial and anthropological studies of African communities in Kenya.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Fazan, “The Pioneers: A Memorandum.”

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Fazan, “East African Pioneer Corps.”

37. Fazan, memorandum entitled “Labor Corps.”

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Fazan, “East African Pioneer Corps.”

42. See Public Works Department Office to Chief Native Commissioner, letter, 5 May 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

43. Fazan, “East African Pioneer Corps.”

44. Ibid.

45. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, “The Pioneer Corps: Historical Record—Preliminary Recruitment and Training,” in “History of War Report,” 6 March 1940, History of War, 1939–48, PC/NZA/2/3/61, KNA.

46. For more of this, see Fazan, “East African Pioneer Corps.”

47. Fazan to the General Staff Officer, letter, 7 November 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

48. District Commissioner, Central Kavirondo, to Chief Elija Bonyo, Sakwa, letter, 15 November 1939, Military Recruitment, DC/KSM/1/22/18, KNA.

49. Fazan to Chief Secretary, confidential letter, 22 January 1939[?], The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

50. Ibid.

51. Divisional Engineer, telegram, 12 June 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

52. Fazan, letter, 6 July 1939.

53. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, “The Pioneer Corps.”

54. Ibid.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Fazan, memorandum entitled “Labor Corps.”

58. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, “The Pioneer Corps.”

59. Report on History of the War, 9 March 1940, History of War, 1939–48, PC/NZA/2/3/61, KNA.

60. Fazan, “The Pioneers: A Memorandum.”

61. Fazan to the Chairman of Man Power Committee.

62. Fazan, letter, “The Pioneer Corps: Band Fund,” 3 November 1939, Military Recruitment, DC/KSM/1/22/18, KNA.

63. Fazan, Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, to Chief Secretary, letter, 29 December 1942, Recruitment of Africans for the Military, PC/NZA/2/3/67, KNA; see also Blundell, Love Affair with the Sun.

64. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner to his District Commissioners, letter, 27 December 1940, History of War, 1939–48, PC/NZA/2/3/61, KNA.

65. Blundell, Love Affair with the Sun, 49.

66. Lt. Col. Bishop to Fazan, letter, 12 December 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

67. Capt. H. E. Humphrey-Moore, Officer-Commanding, 1808 Company, to Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, letter, 7 March 1942, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

68. Fazan to Lt. Col. Bishop, letter, 1 December 1939, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

69. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, “Pioneer Corps.”

70. For detailed analysis of the East African Campaign of 1914–18, some aspects of colonial policies, and how they led to labor shortages, see Hodges, Kariokor; Charles Miller, Battle for the Bundu (New York: Macmillan, 1974); Parson, African Rank-and–File; Melvin E. Page, ed., Africa and the First World War (New York: Macmillan, 1987); Gregory Maddox, “Njaa: Food Shortages and Famines in Tanzania between the Wars,” International Journal of African Historical Studies 19, no. 1 (1986): 17–34; John Overton, “The Origins of the Kikuyu Land Problem: Land Alienation and Land Use in Kiambu, Kenya, 1895–1920,” African Studies Review 31, no. 2 (September 1988): 109–26; B. J. Berman and J. M. Lonsdale, “Crises of Accumulation, Coercion and the Colonial State: The Development of the Labor Control System in Kenya, 1919–1929,” Canadian Journal of African Studies 14, no. 1 (1980): 55–81.

71. Fazan, quoting the two papers and complaining about their editorial in a confidential rejoinder to the chief secretary, letter, 22 January 1940, The Pioneers, 1939–42, PC/NZA/2/3/21, KNA.

72. Nyanza Province Annual Report, 1940, PC/NZA/1/1/35, KNA.

73. Nyanza Province Annual Report, 1941, PC/NZA/1/1/36, KNA.

74. Archival documents show that Fazan commented on virtually every subject of military nature in the colony during the war.

75. Fazan, “The Pioneers: A Memorandum.”

76. Fazan, “Supplementary Notes to Memorandum on the Subject of Military Recruitment,” 11 May 1941, Recruitment of Africans for the Military, PC/NZA/2/3/67, KNA.

77. Fazan, “Memorandum on Military Recruitment,” 31 May 1941.

78. Nyanza Province Annual Report, 1942, PC/NZA/1/1/37, KNA.

79. Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, Nyanza Province Annual Report, 1942, PC/NZA/1/1/37, KNA.

80. The population of adult males in Nyanza Province, according to colonial reports, kept fluctuating. Per the Nyanza Annual Report for 1942, the population of adult males in the province stood at 398,338. However, the “Statistical Notes on Nyanza Native Manpower,” another document authored by colonial administrators, puts the number of males eighteen and above at 394,917 in 1941–42.

81. District Officer, Central Kavirondo, to the District Commissioner, Central Kavirondo, letter, 22 August 1942, Institutions and Associations, 1942–45, PC/NZA/3/1/358, KNA.

82. J. D. McKean, District Commissioner, Kisumu-Londiani to Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, confidential letter, 25 February 1942, Confidential Circulars, 1940, DC/KSM/1/36/47, KNA.

83. Parsons, African Rank-and-File, 82.

84. Acting Nyanza Provincial Commissioner to the Chief Secretary, letter, 9 January 1943, Labor Recruitment, 1943, DC/KSM/1/17/19, KNA.

85. Ibid.

86. Nyanza Province Annual Report, 1942.

87. D. Storrs-Fox, District Commissioner, South Kavirondo, to Nyanza Provincial Commissioner, confidential letter, 20 October 1941, Confidential Circulars, 1940, DC/KSM/1/36/47, KNA.

88. Ibid.

89. See Robert Maxon, “‘Fantastic Prices’ in the Midst of ‘An Acute Food Shortage’: Market, Environment, and the Colonial State in the 1943 Vihiga (Western Kenya) Famine,” African Economic History 28 (2000): 27–52, for a discussion of this issue elsewhere in the colony.

90. Chief Secretary to Provincial Commissioners, letter, 2 November 1942, Recruitment of Africans for the Military, PC/NZA/2/3/67, KNA.

91. Ibid.