1

Dispelling the Myth of Social Darwinism

Before an evolutionary worldview can be established in a positive sense, we must look at the troubled history of social Darwinism. If grave social injustices were committed in Darwin’s name, such as withholding welfare from the poor, forced sterilizations, racial discrimination, and outright genocide, then this is truly dangerous territory. But this rendering of social Darwinism is largely a myth and the true history is far more interesting and complex. Darwin’s theory, properly understood, is centered on cooperation, and Darwin and others were clear about this from the beginning.

NOW AND THEN

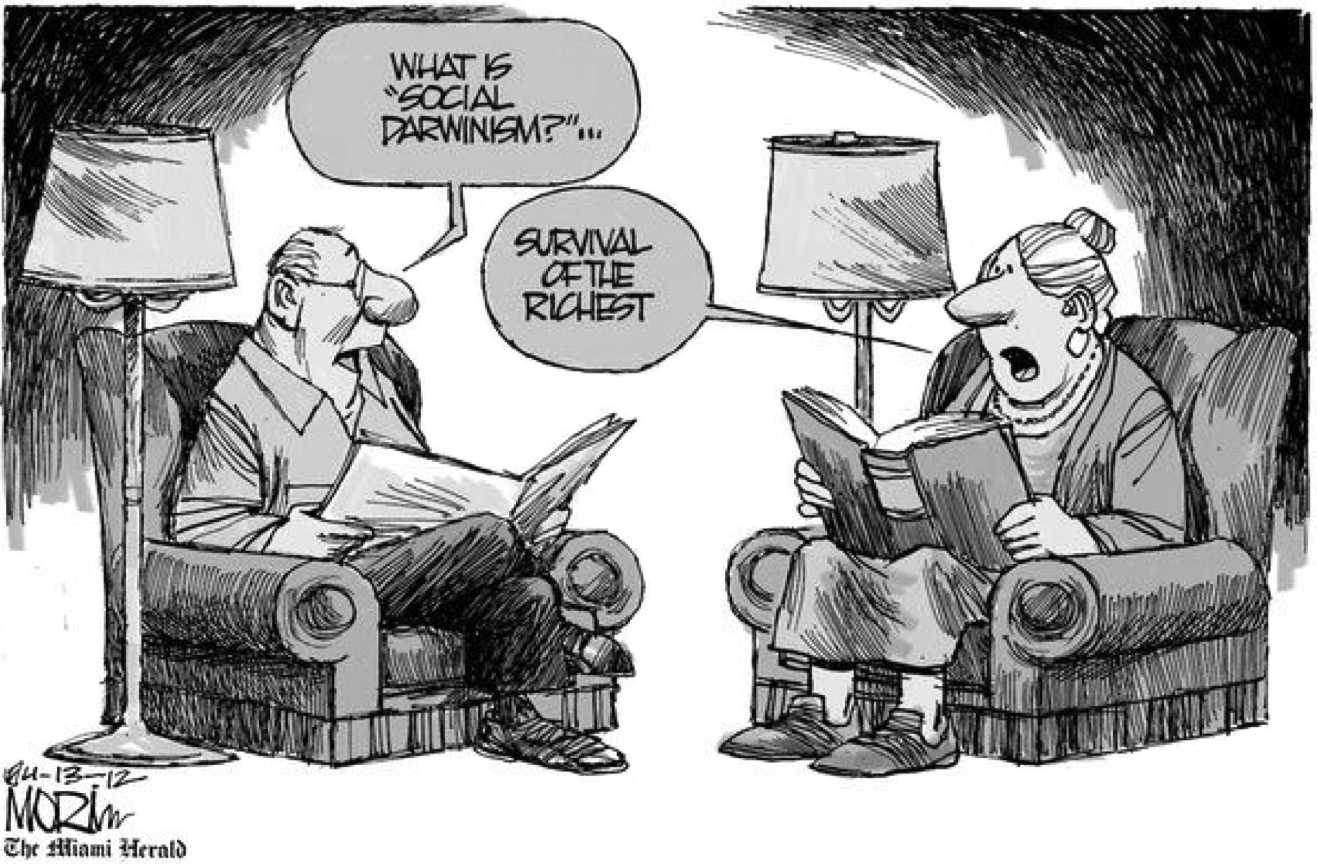

Let’s begin with the modern meaning of the phrase “social Darwinism.” Type it into your favorite search engine and you’ll see thousands of references to the strong gaining at the expense of the weak, as in this cartoon. Former U.S. president Barack Obama was fond of using the phrase in attacks on his Republican opponents, as in a 2012 speech when he called a budget proposed by the U.S. representative Paul Ryan “thinly veiled social Darwinism.”1

Two facts can quickly be established about these usages. First, the phrase “social Darwinism” (or “social Darwinist”) is almost always used as a pejorative to describe someone else’s position. People don’t call themselves social Darwinists. They are called social Darwinists by their opponents. Second, the people who are labeled social Darwinists seldom actually use Darwin’s theory of evolution to justify their position. The idea that Paul Ryan and his associates would use Darwin’s theory to argue in favor of their budget is downright funny, since a vocal portion of this constituency denies evolution altogether!

Today’s meaning of social Darwinism

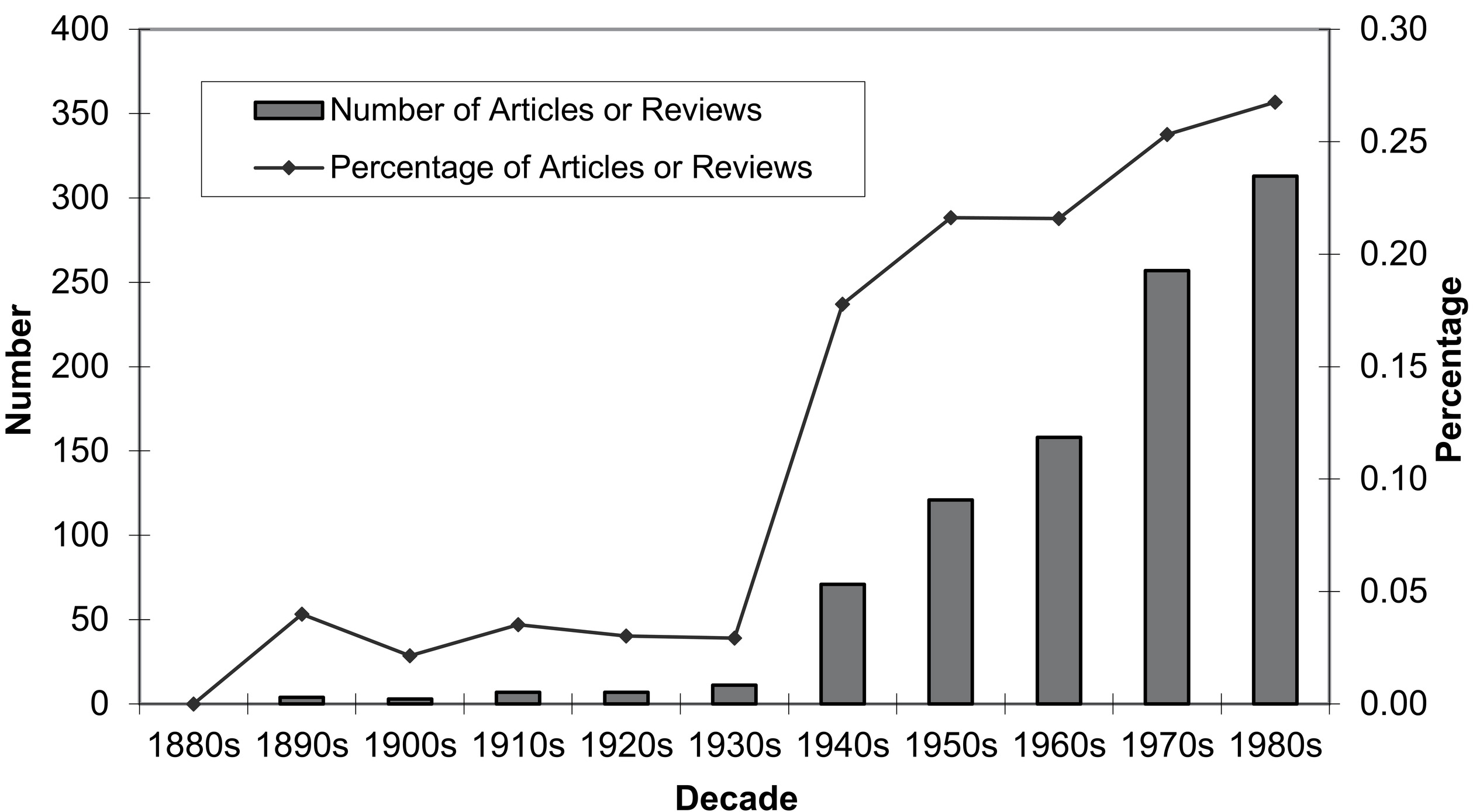

So many books and articles stretching back to the nineteenth century have been digitized that it is possible to comprehensively search for the phrase “social Darwinism” to trace its origins and history of use. Geoffrey M. Hodgson, a contemporary scholar of Darwinism in relation to human affairs, has performed the Herculean task of tracking down every usage of the phrase in JSTOR, an electronic database of academic journals.2 He shows that the phrase began to be used during the late nineteenth century and the context was exactly the same as in the present. As he puts it: “The label was used primarily by leftists to pin upon their opponents.”

Hodgson also discovered that the phrase was hardly used at all until popularized by Social Darwinism in America, a book published by the historian Richard Hofstadter in 1944. This means that during the period when many of the abuses associated with social Darwinism occurred, such as eugenics policies in the United States and Britain and Nazi policies leading to the Holocaust in World War II, the term “social Darwinism” was rarely used by either proponents or opponents of the policies.

To summarize, from the very beginning and throughout its history, the term “social Darwinism” has been used as a pejorative to describe policies that justify the strong taking from the weak in various forms. People hardly ever call themselves social Darwinists and those who are accused almost never actually use Darwin’s theory to justify their position. To a remarkable extent, Darwin’s theory stands falsely accused.

Since the term “social Darwinism” proves to be such an unreliable guide, let’s look back on some of the major protagonists of early evolutionary theory to see what they thought about the role of competition in the betterment of society, including some of Darwin’s predecessors, Darwin himself, and those who were influenced by him.

The term “social Darwinism” was scarcely used at all until the 1940s.

THE CLERIC

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834) was a British cleric and scholar, whose essay on population growth helped both Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace to independently formulate their theories of natural selection.3 Malthus observed that populations will inevitably grow to exceed the capacity of resources available to sustain them and therefore will be checked by famine and disease. As a cleric, he concluded that this situation must be divinely imposed to teach virtuous behavior. Misery was part of God’s plan and should not be impeded by well-meaning but shortsighted attempts to improve the lot of the poor. God’s plan should be allowed to take its course. Needless to say, this was a departure from traditional Christian doctrine, which mandates extending charity to the poor.

Malthus was not totally heartless in the development of his thesis. For example, he thought that moral constraint on the part of the poor was superior to famine and disease, but in either case he argued against the Poor Laws, which was the government’s social welfare system at the time. Malthus’s work, in addition to inspiring the theory of natural selection, influenced the early development of economic theory.

Malthus thought that misery was part of God’s plan to teach virtuous behavior.

THE POLYMATH

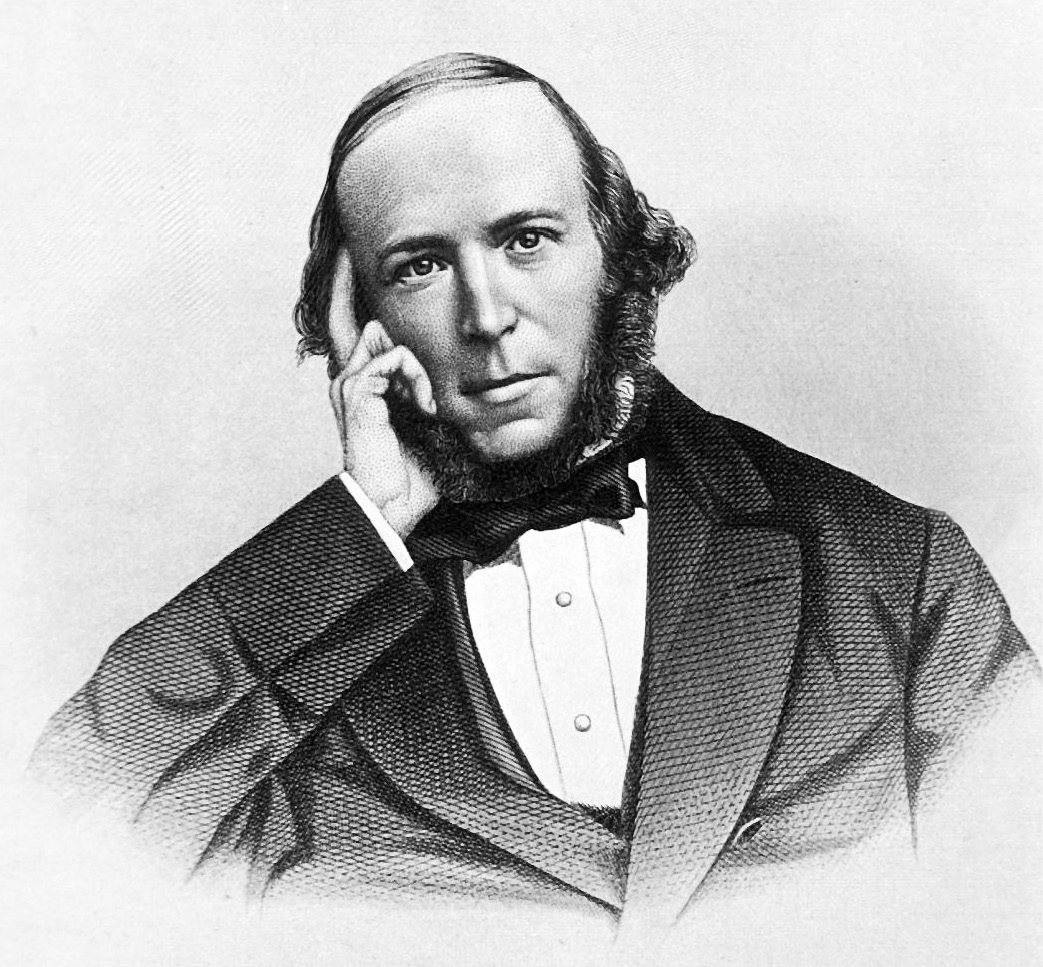

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was regarded as an intellectual giant during Darwin’s day and had his own theory of evolution that preceded Darwin’s.4 Today his star has almost completely faded and none of his ideas about evolution are taken seriously. To understand such a spectacular rise and fall, we must appreciate what Spencer meant to his peers. He represented an effort to create an all-embracing cosmology that could explain everything on the basis of natural laws and could be discovered by scientific investigation. In short, Spencer was offering a substitute for conventional religion that was centered on science. The French philosopher and polymath Auguste Comte (1798–1857) had the same expansive goal to create a “Religion of Man,” but Spencer attempted to organize his cosmology around a single law of progressive development that he called the principle of evolution, which could be applied to all branches of knowledge. It is easy to imagine the appeal of this project for Enlightenment thinkers, however doomed its prospects were over the long term.

Spencer championed women’s rights and opposed imperialism, but he also opposed welfare for the poor.

Spencer was a political radical as a young man, although he became more conservative as he aged. He was against the power of the aristocracy and in favor of a voting privilege for women and even children. He opposed British imperialism and military conquest throughout his life. Nevertheless, his “progressive” views led him to oppose extending social welfare to the poor, along with most other state-controlled activities. For Spencer, humanity was evolving toward perfection without the help of governments, which only got in the way. There is a clear family resemblance between Spencer’s views and the laissez-faire economic policies of today. Spencer departed from Malthus in centering his cosmology on science rather than religion, but he shared Malthus’s view that “survival of the fittest” (a phrase that Spencer coined) played an essential role in the perfection of humanity and therefore should not be impeded by humanitarian impulses and especially not by state-controlled programs.

THE FOUNTAINHEAD

Now we are in a position to consider Darwin’s views on the role of “survival of the fittest” in human society.5 He was progressive by the standards of his day but still very much a product of Victorian culture. He was vehemently against slavery and regarded all races as part of a single human species, but he also regarded European culture as superior and could not conceal his distaste for some of the people that he encountered on his voyage on the Beagle. He took it for granted that men were intellectually superior to women. On eugenics, he assumed that selective breeding practices would work for humans as well as for domesticated plants and animals, but nevertheless counseled against human eugenics because dictating who could breed would violate feelings of sympathy, which he regarded as the glue that holds human society together. As he put it: “Selfish and contentious people will not cohere and without coherence nothing can be effected.”6 Clearly, Darwin placed the emphasis on cooperation rather than competition.

Darwin was passionately against slavery but still regarded European culture as superior, along with almost all other Europeans at the time.

When the term “social Darwinism” began to be used, it did not refer to Darwin’s own views but to the laissez-faire views associated with Spencer and Malthus that were already in place before Darwin made the scene. The epithet bore Darwin’s name because his theory of evolution was the most widely accepted and Spencer’s had fallen out of fashion. The few people who used the phrase weren’t as concerned about making scholarly distinctions between Darwin and Spencer as they were about stigmatizing an opponent.

It was inevitable that others would speculate about the implications of Darwin’s theory for public policy, even if Darwin remained circumspect. Three notables were Francis Galton, Thomas Huxley, and Peter Kropotkin.

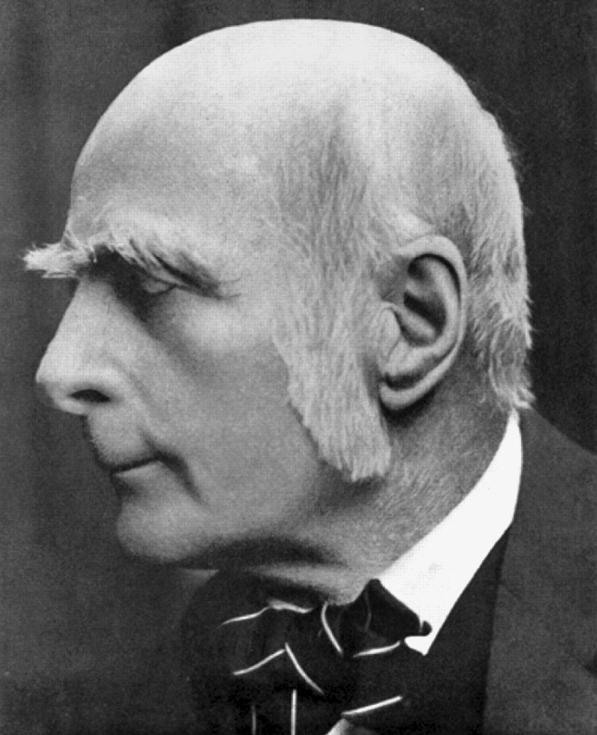

THE COUSIN

Francis Galton (1822–1911) was Darwin’s half cousin and a prolific scientist in his own right.7 He contributed to the early study of statistics in addition to other achievements. He was politically progressive for his day, and his scientific orientation toward all topics led him to study the efficacy of prayer by comparing the longevity of clerics with men of other professions (there was no difference).8 He is the person who coined the word “eugenics” to promote selective breeding for the improvement of humans, using the same principles that had been employed for generations to improve domesticated plants and animals.

By his own account, Galton was inspired by Darwin’s Origin of Species to investigate the heritability of human traits, including everything from fingerprints and facial morphology to mental attributes. His book Hereditary Genius, published in 1869, claimed to provide evidence for the inheritance of human abilities. It made sense to Galton for government to implement programs that favored the reproduction of people with abilities. The particular plan that he advocated was by today’s standards a bizarre mosaic of liberal and conservative ideas. Everyone should receive a first-class education and entrance to professional life. Income should be derived from work rather than inheritance so that everyone has a chance to demonstrate their innate abilities. After the state has provided a level playing field, it should provide unisex monasteries for the weak to live out their lives in comfort without reproducing. Immigrants should be screened for their abilities and the best should be naturalized.

Galton favored a strict meritocracy, arguing against hereditary privilege and for accepting talented immigrants.

THE BULLDOG

Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895) was born into a middle-class family that fell upon hard times.9 He had only two years of formal schooling but nevertheless educated himself to become one of the foremost biologists of his day, specializing in comparative anatomy. Like Darwin, he embarked upon a sea voyage as a young man (as a surgeon’s mate on the HMS Rattlesnake) and made biological investigations that earned him a reputation back home. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society at the age of twenty-six. He was skeptical about the evolutionary theories that preceded Darwin but became convinced about the fact of evolution by On the Origin of Species, even though he remained less certain about the centrality of natural selection (in general, the concept of identity by descent was accepted more quickly by Darwin’s peers than natural selection as the driving force of evolution).10 Combative, eloquent, and extroverted, Huxley described himself as “Darwin’s bulldog” in defending Darwin against his critics.

Huxley ridiculed eugenics as a “pigeon fancier’s polity.”

Huxley’s views on evolution in relation to human affairs were expressed in “Evolution and Ethics,” an essay written a few years before his death and still in print today. Huxley rejected Galton’s eugenic vision, lampooning it as a “pigeon fancier’s polity,” because no one is smart enough to identify the abilities of people, especially at a young age. Huxley must have had in mind his own experience as someone who was not born into privileged society when he wrote: “I doubt whether even the keenest judge of character, if he had before him a hundred boys and girls under fourteen, could pick out, with the least chance of success, those who should be kept, as certain to be serviceable members of the polity, and those who should be chloroformed, as equally sure to be stupid, idle, or vicious.”11

Nevertheless, Huxley thought that some kind of selection was required to create a moral society. The natural world is not moral and human society left unmanaged isn’t either. Our evolved passion for pursuing our own self-interest would lead to the destruction of society unless somehow constrained. Fortunately, in addition to our self-aggrandizing instincts, we also have instincts that can be used to create a moral society, not least our passion to maintain a good reputation: “I doubt if the philosopher lives, or ever has lived, who could know himself to be heartily despised by a street boy without some irritation.”12 We therefore need to work with what evolution has provided us to cultivate a moral society that works for the benefit of all, in the same way that we cultivate a garden.

Huxley was among the most gifted writers of his age, and his critique of the “survival of the fittest” worldviews of Malthus, Spencer, and Galton (bearing in mind that each of these men formulated different versions, as we have seen) is worth savoring.

It strikes me that men who are accustomed to contemplate the active or passive extirpation of the weak, the unfortunate, and the superfluous; who justify that conduct on the ground that it has the sanction of the cosmic process, and is the only way of ensuring the progress of the race; who, if they are consistent, must rank medicine among the black arts and count the physician as mischievous preserver of the unfit; on whose matrimonial undertakings the principles of the stud have the chief influence; whose whole lives, therefore, are an education in the noble art of suppressing natural affection and sympathy, are not likely to have any large stock of these commodities left. But, without them, there is no conscience, nor any restraint on the conduct of men, except the calculation of self-interest….13

Huxley’s views were similar to Darwin’s on this point, but far more forcefully expressed. The bulldog indeed had a fierce bite.

THE ANARCHIST

Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) was a Russian prince who became a prominent anarchist, arguing for a communist society free from central government.14 Kropotkin’s father owned large tracts of land inhabited by over a thousand serfs. The son’s proclivities toward equality emerged early, and at the age of twelve he stopped using his princely title. Like Darwin and Huxley, Kropotkin traveled widely (although by land instead of sea) and conducted scientific investigations, centered on geology but including observations of animals and the many indigenous cultures making up the Russian Empire. He was imprisoned repeatedly for his revolutionary activities and also spent periods in exile in Britain, Switzerland, and France. He returned to Russia as a hero in 1917 but became disillusioned when the Bolsheviks seized power.

Kropotkin’s main contribution to evolutionary theory was his book Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution, which was published in 1902. He argued that the emphasis on competition among individuals was misplaced and an artifact of British capitalism. In reality, most species live in groups whose members provide mutual aid to each other in their common struggle against the environment. Kropotkin also claimed that indigenous human societies were primarily cooperative and that this form of cooperation could provide a model for modern society without the need for a strong central government. It is interesting how the views of Kropotkin converge with those of Spencer on this libertarian point, despite profound differences in other respects.

Kropotkin regarded mutual aid as the main survival tool of humans and other animals.

A RAIN FOREST OF OPINIONS

Six major theorists—Malthus, Spencer, Darwin, Galton, Huxley, and Kropotkin—each with their own views on the role of competition in the betterment of human society. Malthus justified his views in terms of religion and Spencer in terms of a secular cosmology that used the word “evolution” but otherwise bore little resemblance to Darwin’s theory. Spencer’s views on social welfare fit the stereotype of social Darwinism, but not his views on aristocracy, imperialism, and military conquest. Galton’s views on eugenics fit the stereotype of social Darwinism but not his views on providing a level playing field. Malthus, Spencer, and Kropotkin argued against “big government” while Galton expected his eugenic utopia to be orchestrated by the state. Malthus, Spencer, and Galton saw competition as a source of societal improvement, but Darwin, Huxley, and Kropotkin emphasized the corrosive effects of unbridled self-interest and the essential role of cooperation.

What are we to make of all this variety? Evolutionary theory meant different things to different people, which is only to be expected when an important new idea starts to interact with one’s current worldview. As for these six major figures, so also for thousands of other people as Darwin’s theory started to become known and discussed around the world.15 There was a veritable rain forest of opinions in the discussions surrounding early evolutionary theory. Decades would be required to sort among them, just as decades were required to sort out the implications of Darwin’s theory for the biological world. But with respect to human society, that process was largely halted by the false view that Darwin’s theory leads to nothing but pernicious outcomes.

HITLER AND DARWIN

One of the most common claims about Darwinism is that it contributed to the genocidal horrors of Nazi Germany. Before examining the evidence, what should we conclude if this claim turns out to be true? Would it mean that we should avoid evolutionary theory in the formulation of public policy?

Even a brief reflection should convince you that the answer to this question is “no.” Almost anything that can be used as a tool can also be used as a weapon. Do we avoid physics because it can lead to the atomic bomb? Do we avoid chemistry because the Nazis used chemicals in their gas chambers? Do we blame Mendel for misuses of genetics? The entire concept of making a scientific theory and its originator morally culpable for misuses of the theory is deeply misguided.

That said, there is no evidence that Hitler or his associates were influenced by Darwin, either directly or indirectly through Darwin’s German colleague and friend, Ernst Haeckel. The distinguished historian of science Robert Richards has clearly demonstrated this point in his essay “Was Hitler a Darwinian?”16

Focusing on Darwin ignores the deep roots of racism in general and anti-Semitism in particular in European thought. It’s hard to find a major figure who didn’t arrange humans into a hierarchy of races with Europeans at the top. Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778), the great classifier of plants and animals, divided Homo sapiens into four categories, each with their own temperaments: American (copper-colored, choleric, regulated by custom), Asiatic (sooty, melancholic, and governed by opinions), African (black, phlegmatic, governed by caprice), and European (fair, sanguine, and governed by laws). Since Linnaeus was a creationist, he assumed that these differences were divinely ordained.

Darwin, himself, took a hierarchy of races for granted but wrote almost nothing about Jews. Haeckel did include Jews in his racial hierarchy but ranked them at the same level as Germans and other Europeans. In an interview conducted in the 1890s, Haeckel stated: “I hold these refined and noble Jews to be important elements in German culture. One should not forget that they have always stood bravely for enlightenment and freedom.”17 So much for Haeckel’s influence on Hitler!

Hitler and his associates drew upon books such as the four-volume Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, by Joseph Arthur, comte de Gobineau (1816–1882), and The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, by Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), who was part of a cult that formed around the composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883). Gobineau developed his thesis that race mixing was responsible for the decline of human societies prior to Darwin and disdainfully dismissed Darwin’s theory. Chamberlain dismissed as “pseudo-scientific fantasy” Darwin and Haeckel’s argument that humans were descended from apelike ancestors.

The connection between Hitler and Chamberlain is plain to see. Hitler read Chamberlain’s book sometime between 1919 and 1921. They met when Hitler visited Wagner’s home and shrine in 1923. Chamberlain was among the first of Hitler’s supporters, and Hitler attended Chamberlain’s funeral in 1927. In contrast, the historical record includes no mention of Hitler discussing Darwin’s theory of evolution until 1942, when he said: “Whence have we the right to believe that man was not from the very beginning what he is today? A glance at nature informs us that in the realm of plants and animals alterations and further formation occur, but nothing indicates that development within a species has occurred of a considerable leap of the sort that man would have to have made to transform himself from an apelike condition to his present state.”

As Richards remarks after quoting this passage, could any statement rejecting Darwin’s theory of evolution for the human case be more explicit? Elsewhere in his essay, Richards compares the search for connecting Darwin to Hitler as similar to seeing animal shapes in clouds or the game of six degrees of separation, which could equally be played to connect Hitler to Aristotle or Jesus. When it comes to influencing the genocidal horrors of Nazi Germany, Darwin’s theory is clearly not responsible.

DEWEY AND DARWIN

If a contest were to be held for the opposite of the stereotypic social Darwinist, the winner might well be John Dewey (1859–1952), the American philosopher, psychologist, educator, and social reformer.18 Yet, Darwin’s influence on Dewey is as plain to see as Chamberlain’s influence on Hitler. The reason that no one calls Dewey a social Darwinist is because the term is used entirely as a pejorative, giving the misleading impression that anyone who falls under the spell of Darwin is going to end up thinking like Hitler.

Dewey represented the philosophical tradition of Pragmatism, which originated during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries among a small group of American intellectuals, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charles Sanders Peirce, and William James. Their stories are beautifully told by Louis Menand in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book The Metaphysical Club. They realized that if the human mind is a product of natural selection, then knowledge must be based on its practical consequences rather than a God-given apprehension of objective reality. This was a radical new approach to epistemology, the branch of philosophy devoted to understanding the nature of knowledge.

By the time John Dewey attended college at the University of Vermont and graduate school at Johns Hopkins University, Darwin, Spencer, and the Pragmatists were part of his education. Although Spencer is remembered today for his laissez-faire attitudes toward the poor, his broader philosophical view emphasized the intimate relationship between organisms and their environments. In fact, the word “environment” was seldom used prior to the mid-nineteenth century, as strange as this might seem to us today. It was Spencer, not Darwin, who popularized its use. Darwin used terms such as “conditions” and “circumstances” and didn’t start using the term “environment” until late in his career.

Dewey found it easy to embrace Spencer’s emphasis on an organism-environment relationship while rejecting his laissez-faire attitude toward the poor. For Dewey, pragmatism meant “the applied and experimental habit of mind.” In what he called an “evolutionary method,” any given moral norm or mode of reasoning is “treated as an instrument of adjustment or adaptation to a particular environing situation.” In other words, Dewey thought about evolution as a process taking place among beliefs and practices in the present, not just selection among genes that took place in the ancient past. This placed him close to Teilhard de Chardin and the modern concept of “niche construction” that will be discussed in this book.

Dewey represents the philosophical tradition of Pragmatism, which was heavily influenced by Darwin.

Dewey’s experimental approach led him to found the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago, which is still going strong. The idea that a school might serve as a laboratory for evolving best educational practices was a radical innovation at the time. He also worked closely with other second-generation Pragmatists such as Jane Addams, George Herbert Mead, and W. E. B. Du Bois, who are beloved as social reformers and champions of democracy and therefore never associated with the term social Darwinism.

Here is what Dewey had to say about Darwin in the title essay of his 1910 book, The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy:

In laying hands upon the sacred ark of absolute permanency, in treating the forms that had been regarded as types of fixity and perfection as originating and passing away, the “Origin of Species” introduced a mode of thinking that in the end was bound to transform the logic of knowledge, and hence the treatment of morals, politics, and religion.19

For Dewey, “evolution” meant “change,” with human agency having an essential role in the construction of a moral society.

THE CREATION OF A BOGEYMAN

As we have seen from Geoffrey Hodgson’s meticulous analysis, the phrase “social Darwinism” was seldom used before it was popularized by the historian Richard Hofstadter (1916–1970) in his 1944 book Social Darwinism in American Thought. World War II was not a time for dispassionate scholarly analysis. As Hodgson puts it, “The skills of a great historian were deployed in the ideological war effort against fascism and genocide.” Any view that promoted racism, nationalism, or competitive strife qualified as social Darwinism in Hofstadter’s book.

Other forces were at work that created a separation between Darwin’s theory in the biological sciences and the same theory in relation to human affairs. Darwin knew nothing about genes and formulated his theory in terms of variation, selection, and heredity—a resemblance between parents and offspring due to any mechanism. Once the science of genetics was born in the early twentieth century, however, genes came to be treated as the only mechanism of inheritance, as if there were no other way for offspring to resemble their parents. This is patently false, but the study of cultural inheritance mechanisms did not re-emerge within the biological sciences until the 1970s.20

Sociologists, for their part, had their own reasons for declaring independence from biology, and those reasons had nothing to do with the supposed evils of social Darwinism. In order to establish the study of society as a separate field of inquiry, they had to assert that it couldn’t be “reduced” to biological or even psychological facts. The American sociologist Talcott Parsons used the term “social Darwinism” in this way, to refer to strictly biological influences, not including the kind of social constructivism that Dewey was happy to call evolutionary.21

In this fashion, evolution became widely regarded as a powerful theory for explaining the rest of life, the physical human body, and a few basic survival instincts—while having nothing to say about our rich behavioral and cultural diversity. Along the way, evolution and “biology” became associated with an incapacity for change (being stuck with our genes), with our capacity for change somehow residing outside the orbit of evolution.

The term “social Darwinism” helps to buttress this bizarre configuration of ideas in ways that are almost childish, once they are seen clearly. Here is how Geoffrey Hodgson puts it:

The woods can be dangerous. So we might tell children stories of woodland beasts or bogeymen, to warn them away from the forest. Similarly, prevailing accounts of “Social Darwinism” have been invented as bogeyman stories, to warn all social scientists away from the darkened woodland of biology. We are told that any use of ideas or analogies from biology in the social sciences is unsafe. We are warned not to stray into that biological zone, for terrible things will happen, as they surely happened before. But scientists should not be treated as children…Let us stop telling false histories, and henceforth call things by their proper names.

THE BIGGEST VICTIMS

Darwin’s theory can and has been misused by some people. However, the same can be said for any theory and indeed for almost any tool of any sort. There is no evidence that Darwin’s theory is especially prone to misuse, so using the term “social Darwinism” as a bogeyman has no place in serious scholarship or science. It’s clear that policies classically considered social Darwinism actually have almost nothing to do with a proper reading and understanding of Darwin’s theory.

Who are the biggest victims of this stigmatization? All of us. Evolutionary theory has made enormous progress within the biological sciences while remaining almost entirely excluded from the many branches of the human social sciences and humanities and their practical applications. Now that we have dispelled the myth of social Darwinism as a bogeyman, we can begin to explore how an evolutionary worldview can function in a positive sense to consciously evolve our collective future.