6

What All Groups Need

By now I hope you can see how an evolutionary worldview encompasses the length and breadth of human experience in addition to the biological sciences. This is something that Darwin appreciated from the beginning, but only now is the rest of the world catching on. “This View of Life,” as Darwin put it, is doubly exhilarating. First, it provides a new view of the big questions pondered by deep thinkers throughout the ages, such as the nature of morality. Second, it provides new insights for improving the quality of our lives in a practical sense, from our well-being as individuals, to the myriad groups that we join to get things done, to our governments, economies, and ultimately the entire planet.

I started to explore the practical insights over a decade ago by getting involved in my hometown of Binghamton, New York, and helping to start the Evolution Institute, the first think tank to formulate public policy from a modern evolutionary perspective.1 In the following chapters, I will recount my own experience in addition to reporting on the work of others.

You might think that the best way to report on individuals, groups, and large-scale society would be in that order. Starting at the smallest scale would make sense in the grand tradition of reductionism, which seeks to understand things by taking them apart. A version of reductionism common in the social sciences is called methodological individualism, a commitment to the belief that all social phenomena can and should be reduced to the motives and actions of individuals.2 A version of methodological individualism common in the economics profession is called Homo economicus, a portrayal of individuals as motivated entirely by self-interest, usually conceptualized as the pursuit of wealth.3

An evolutionary worldview provides a refreshing alternative to these reductionistic traditions. Multilevel selection theory tells us that analysis should be centered on the unit of selection. Imagine that you are a biologist studying a solitary insect such as a fruit fly. You would study individual flies in relation to their environment to address Tinbergen’s function and history questions. Then you would shift to lower levels such as organs, cells, and molecules to ask Tinbergen’s mechanism and development questions.

Now imagine that you are a biologist studying a social insect such as honeybees. Since the colony is the primary unit of selection, that is the unit that you would focus on to address Tinbergen’s function and history questions. You wouldn’t begin at the level of individual bees any more than the fruit fly biologist would begin at the level of the fly’s organs. This is a powerful refutation of methodological individualism, which states that individuals should always be the center of analysis.4

If it is true that we are a highly group-selected species, at the scale of small groups during our genetic evolution and progressively larger societies during our cultural evolution, then these groupings should be the center of our analysis, as surely as honeybee colonies are for the biologist. A sports analogy might help to make this intuitive. Suppose that you’re watching a football game. The ball snaps and one of the wide receivers takes off down the field, darting first to the left and then to the right before stopping. The quarterback has thrown the ball to one of the tight ends. The wide receiver played an important role by drawing attention away from the tight end, and could have received the ball if the tight end had been covered too closely, but his behavior is impossible to understand in isolation. It only makes sense in the context of a coordinated team effort.

This example is easy to understand because we know that a sports team is strongly selected to function well as a unit. Parenthetically, when a team doesn’t function well, it is often because of disruptive self-serving competition among members within the team. Coaches preach that there is no “I” in “TEAM” to suppress the temptation to strive for individual glory, which is felt more strongly by some team members than others. Research shows that too much disparity in the salaries of members of professional sports teams undermines their cohesion as a group.5 Conflicts between levels of selection are on full display in the sports world, but between-team selection is strong enough to result in the team-level coordination that we see.

Multilevel selection theory tells us that something similar to team-level selection took place in our species for thousands of generations, resulting in adaptations for teamwork that are baked into the genetic architecture of our minds.6 Absorbing this fact leads to the conclusion that small groups are a fundamental unit of human social organization. Individuals cannot be understood except in the context of small groups, and large-scale societies need to be seen as a kind of multicellular organism comprising small groups.

For this reason, the next three chapters are sequenced in the order groups, individuals, and large-scale societies. Groups need to come first in our analysis because well-functioning groups are required for both individual well-being and efficacious action at larger scales. If you’re not surrounded by nurturing others who know you by your actions, then it will be difficult for you to thrive as an individual. If you’re not part of a group that is committed to advancing a worthy cause, then you are unlikely to have the resolve and resources to advance the cause on your own.

Here are some stories that show what all groups need to function well, which is often obscured from other perspectives but makes great sense when we are equipped with the right theory.

LIN’S LEGACY

A life-changing experience for me, after deciding to apply evolutionary theory to the solution of real-world problems, was working with Elinor Ostrom, who received the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009. Lin, as she insisted everyone should call her, was a political scientist by training and largely unknown to economists at the time she won their most coveted honor. Steve Levitt, the University of Chicago economist and co-author of the bestseller Freakonomics, confessed that he had to look her up on Wikipedia and predicted that his colleagues would hate the prize going to her because it signified that “their” prize was becoming one for all of the social sciences.7 Economics was falling off its pedestal.

What did Lin do that was so important? She studied a problem called “the tragedy of the commons,” made famous by the ecologist Garrett Hardin in an article published in the journal Science in 1968.8 Hardin asked the reader to imagine a village with a common pasture that was available for all of the villagers to graze their cows. The pasture can support only so many cows, but each villager has an incentive to add more of his cows to the herd, resulting in the tragedy of an overgrazed pasture. Hardin’s example became a parable for the problem of managing common-pool resources of all sorts, such as pastures, forests, fisheries, irrigation systems, groundwater, and the atmosphere.

Economists have difficulty seeing the tragedy of the commons because of their firm belief that the pursuit of individual self-interest robustly benefits the common good. When they do acknowledge the problem posed by Hardin’s parable, their two main solutions are to privatize the common resource (if possible) or to impose top-down regulations.

A high point of my life was working with Elinor Ostrom, who received the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009.

Against this background, Lin’s work was indeed revolutionary.9 Unlike the orthodox economics establishment, which supports its ideas primarily with mathematical equations, Lin led an effort to compile and analyze a worldwide database of groups that attempt to manage common-pool resources. Some of these groups were capable of avoiding the tragedy of commons on their own, without privatization or top-down regulation. The economists were blind to something that was taking place in the real world.

An outstanding example was a group of about a hundred fishermen operating out of Turkey’s coastal city of Alanya. Before the 1970s, this fishery was largely unregulated. About half of the fishermen belonged to a local producers’ cooperative, but the other half could do as they pleased. Competition for the best fishing spots led to uneven use of the whole area, more uncertainty about any fisher’s catch, increased production costs, and hostilities that at times escalated to violence. All of these dysfunctions can be regarded as tragedies of the commons writ large, including but also going beyond depleting the fish population.

Then a system emerged from the cooperative, was perfected over a period of years, and largely solved these problems. All licensed fishers were eligible to join the system, not just members of the cooperative. The total area being fished was divided into a number of locations spaced far enough apart so that nets set in one area would not interfere with nets set in adjacent areas. Starting every September, eligible fishers drew lots and were assigned to the named fishing locations. At periodic intervals, they rotated their locations so that each fisher had equal access to the best areas over the long term.

This arrangement was so fair that it was easy for all of the fishers to agree to it, regardless of whether they belonged to the cooperative. It saved everyone the effort of searching and fighting over sites. It was also easy to monitor, because anyone who fished where they weren’t supposed to was caught out by the ones who were playing by the rules.

Not all of the groups in Lin’s database managed their resources so well. Some were failing, just as this particular group of Turkish fishers were failing prior to the 1970s. Lin’s great achievement was to derive eight core design principles (CDPs) that made the difference between success and failure. These were what all of the groups needed but only some of them had figured out for themselves.

Without further ado, here are the eight CDPs. As I list them, think about whether they might be relevant to the groups in your life.

-

CDP 1. STRONG GROUP IDENTITY AND UNDERSTANDING OF PURPOSE. The most successful groups knew the boundaries of their resource, who was entitled to use it, and the rights and obligations of being a group member. This was clearly the case for the Turkish fishers, who knew who was licensed and the area that they were authorized to fish.

-

CDP 2. PROPORTIONAL EQUIVALENCE BETWEEN BENEFITS AND COSTS. Having some members do all the work while others get the benefits is unsustainable over the long term. In the groups that functioned well, everyone did their fair share. When leaders were accorded special privileges, it was because they had special responsibilities for which they were held accountable. Unfair inequality poisons collective efforts. The system invented by the Turkish fishermen worked only because it was scrupulously fair.

-

CDP 3. FAIR AND INCLUSIVE DECISION-MAKING. In the groups that functioned well, everyone took part in the decision-making—if not by consensus, then by some other process recognized as fair. People hate being bossed around but will work hard to accomplish agreed-upon goals. In addition, the best decisions often require knowledge of local circumstances that group members possess and top-down regulators don’t. In the case of the Turkish fishers, everyone had to agree to the arrangement and only they were knowledgeable enough to divide the total area into its sectors. Also, years were required to perfect the system and only members of the group were in a position to know what needed adjusting.

-

CDP 4. MONITORING AGREED-UPON BEHAVIORS. Even when most members of a group are well meaning, the temptation to do less and take more than one’s share is always present and a few members might try to actively game the system. The most successful groups in Lin’s database were good at detecting lapses and transgressions, as we have seen for the Turkish fishers.

-

CDP 5. GRADUATED SANCTIONS. If someone isn’t doing their part, then a friendly reminder is usually sufficient to return them to solid citizen mode—but tougher measures such as punishment and exclusion must also be available when needed. One of Lin’s favorite examples of this and the other CDPs involved the lobster fishermen of Maine in the United States. Like the Turkish fishers, the lobstermen were organized into “gangs” that had exclusive use of sections of shoreline (CDP 1). Each lobsterman paints his buoys in a distinctive fashion so they can monitor each other’s trapping and detect the presence of outsiders (CDP 4). When an outsider sets traps in their area, the resident lobstermen begin the process of graduated sanctions by tying a bow around the buoys (CDP 5). Lin especially enjoyed telling this part of the story. “A bow!” She would laugh. “Can you imagine those big burly lobstermen tying bows around the interloper’s buoys!” Of course, tougher measures will follow if the interloper doesn’t take the hint and leave the area.

-

CDP 6. FAST AND FAIR CONFLICT RESOLUTION. Conflicts of interest are likely to arise in almost any group. The best groups in Lin’s database had ways to resolve them quickly in a manner that was regarded as fair by all parties. That is why an organization such as a cooperative is needed, although it need not rely on outside authority.

These picturesque buoys allow lobstermen to monitor each other’s trapping behavior and detect outsiders.

-

CDP 7. LOCAL AUTONOMY. When a group is nested within a larger society, then it must be given enough authority to create its own social organization and make its own decisions, as outlined by CDPs 1–6. This was clearly the case for the Turkish fishers. When other groups in Lin’s database failed to manage their common-pool resource, it was often because they weren’t provided the same kind of elbow room.

-

CDP 8. POLYCENTRIC GOVERNANCE. In large societies that consist of many groups, relationships among groups must embody the same principles as the relationships among individuals within groups. This means that the core design principles are scale-independent, a point that will become important when we turn our attention to large-scale societies in chapter 8. The Turkish fishers did rely on larger-scale governance (for example, the court system) for such things as licensing and extreme conflict resolution, but in a way that contributed to the implementation of the CDPs rather than disrupting them.

Unlike orthodox economics, which is math-rich and data-poor, the CDPs are based on the study of real-world groups such as Turkish fishers and the lobster gangs of Maine. They have been affirmed by subsequent research on common-pool resource groups that followed upon Lin’s pioneering studies.10 Hence, they are highly trustworthy. Let’s take a moment to reflect upon them. Notice how sensible they are. None of them are surprising, really. Another thing you might notice is how general they are likely to be. Why should they be restricted to common-pool resource groups? How about schools, neighborhoods, churches, volunteer organizations, businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies? In a sense, the very act of working together to achieve a common goal is a common-pool resource. Additional research will be required to confirm the generality of the CDPs, but intuitively it appears highly likely.

A third thing you might notice is that even though the CDPs make great sense for almost any kind of group, sadly they are not implemented by many groups. That’s what Lin found for the groups in her database. Only some did a good job managing their common-pool resources. Others succumbed to the tragedy of overuse and other failures of cooperation. If the CDPs are so sensible, beneficial, and general, then why aren’t they universally adopted?

Finally, even though the CDPs might seem obvious in retrospect, they weren’t at all obvious to the economics profession, which is why Lin merited their highest honor. Nothing is obvious all by itself. All policies “make sense” against the background of their assumptions, but the wrong assumptions can make people blind to the importance of the CDPs. Not only was this true for economic theory and policy, but it is true for other topic areas such as education, as we will see.

I met Lin for the first time in 2009, a few months before she was awarded the Nobel Prize. That was the year of Darwin—the 200th anniversary of his birth and 150th anniversary of the publication of Origin of Species. Events were being held all over the world, including a workshop titled “Do Institutions Evolve?” that both Lin and I attended. It took place in a villa in the hills of Tuscany, a short distance from Florence, Italy.11

Although Lin was largely invisible to the economics world, her work was well known to me and my colleagues interested in human social evolution. The title of her most influential book, published in 1990, was Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. She told me that her use of the word “evolution” was mostly colloquial at the time, but that over the years she had increasingly adopted a more formal evolutionary perspective.

As we talked in the idyllic setting, I began to realize how much Lin’s CDP approach dovetailed with multilevel selection theory and the saga of human genetic and cultural evolution that I have related in the last two chapters. In groups that strongly implement the CDPs, it is difficult for members to benefit themselves at the expense of each other, so that the only way to succeed is as a group. Those are the same conditions required for a major evolutionary transition, which converts a group of organisms into an organism in its own right. Lin’s work didn’t just follow from her school of thought within political science and her study of common-pool resource groups. It was far more general than that. It followed from the evolutionary dynamics of cooperation in all species and our own history as a highly cooperative species.

Multilevel selection theory helps to explain why the CDPs are not more widely adopted by groups. They probably would be if selection took place only at the group level, but there is always the temptation to benefit oneself at the expense of others or the group as a whole, which results in subversion of the CDPs. These efforts might be conscious or unconscious. They might even be well intentioned, as when someone feels certain that they know what’s best for the group and tries to override the opinions of others (a violation of CDP 3). Externally, the core design principles can be violated by other groups (violating CDPs 7 and 8). The CDPs must be implemented strongly enough to withstand these internal and external pressures, which doesn’t always happen.

Lin and I worked together for the next three years, and with her postdoctoral associate Michael Cox (now a faculty member at Dartmouth University), we wrote an academic article titled “Generalizing the Core Design Principles for the Efficacy of Groups,” which placed her work on a more solid evolutionary foundation than ever before.12

The generalized version of the CDPs affirms the likelihood that they are needed by nearly any human group whose members are trying to work together to achieve common goals. However, this does not mean that they are sufficient. Almost all groups need the CDPs because they all need to cooperate in one way or another, but they might also need additional design principles to accomplish their particular objectives or to manage particular constraints. These can be called auxiliary design principles (ADPs), and they are as important for the groups that need them as the CDPs. For example, there are dozens of student groups at my university and all of them must be organized with a high turnover of their members in mind, since this is a fact of life for student groups. Not so for many common-pool resource groups, which can be designed with much lower turnover of their members.

Another important point that Lin stressed in her own work is the difference between a functional design principle and its implementation. Take monitoring (CDP 4) as an example. Every group needs to monitor agreed-upon behavior, but there are many different ways to monitor and some might be easier to implement than others for a given group. The fact that each principle can be implemented in different ways is similar to the interplay between Tinbergen’s function and mechanism questions. In Lenski’s E. coli experiment, each population functionally achieved the same outcome by processing glucose more efficiently, but each population achieved this by means of a different mechanism. Similarly, nearly all human groups can benefit from the CDPs (and the appropriate ADPs), but each group must find the best implementations, which can depend critically on local knowledge. This means that the design principles cannot be implemented in a cookie-cutter fashion.

Placing Lin’s work on a general evolutionary foundation has profound implications for public policy. It provides a functional blueprint for any group, anywhere in the world, whose members need to work together to achieve common goals. Think of the groups in your life—your neighborhood, your school, your workplace, your church, the informal groups that you form with your friends and associates to get things done. All of them can be expected to vary in how well they accomplish their objectives, and most of them can be improved by more strongly implementing the core (and auxiliary) design principles. It is not an exaggeration to say that widespread implementation of this approach can make the world a better place—although it is important to add that relationships among groups (CDPs 7–8) must be managed in the same way as relationships among individuals within groups (CDPs 1–6). Otherwise, we are faced with the specter of groups that function well for themselves but at the expense of other groups and the larger-scale society as a whole.

Ever since my collaboration with Lin, I have been promoting the generalized core design principles approach in two ways: first, by analyzing existing information for different types of groups, similar to Lin’s analysis of common-pool resource groups; and second, by working with real-world groups to improve their efficacy. Let’s begin with schools, a particular kind of group tasked with educating our children.

SCHOOLS

Soon after I started working with Lin, the Binghamton City School District asked me to advise them in the creation of a “school within a school” for at-risk ninth and tenth graders that would be called the Regents Academy. I eagerly accepted their invitation as an opportunity to employ the design principles approach in my own hometown. Like many American public high schools, the Binghamton High School attempts to provide a quality education for several thousand students, succeeding better for some than for others. My own two children fell on each side of the divide. My older daughter, Katie, graduated with top honors and went on to a top college. My younger daughter, Tamar, became so unhappy in middle school that we home-schooled her for a year and a half and then enrolled her in a Quaker boarding school in Pennsylvania, where she thrived and then went on to a top college.

Of course, many people don’t have the luxury of sending their children who struggle in public school to a boarding school. And children born on the wrong side of the tracks have a very different experience than more privileged children. The “school within a school” was an attempt to help ninth and tenth graders who had failed at least three of their courses during the previous year and were very likely to drop out if nothing was done.

It was strange to review my parental experience through the lens of the core design principles. Even without making a formal study of it, I could see that the Quaker boarding school scored high. First and foremost, it was small enough for the teachers and students to know each other as individuals (CDP 1). The students were held to high standards, but they were recognized for their contributions (CDP 2). The Quaker religion is famously egalitarian and I was moved the first time I entered the 200-year-old meeting house, with the pews arranged in concentric squares around an empty central space (CDP 3). Student performance was closely monitored, and other forms of monitoring could easily take place in a small residential community (CDP 4). Misbehaviors were flagged early and dealt with in a compassionate fashion, but persistent deviance was more severely punished and cases of expulsion were known (CDP 5). There were well-oiled conflict resolution procedures borrowed from the Quaker tradition (CDP 6). As its own independent entity, the school had maximum authority to govern its own affairs (CDP 7), and most of its relationships with other organizations appeared to be collaborative and benign (CDP 8). No wonder that Tamar blossomed there!

Many schools are sadly lacking in the core design principles, especially for at-risk students.

In contrast, the Binghamton High School appeared lacking in many of the same principles. It was too big to function as a single group where everyone knows each other. Some students had strong school spirit, but many others didn’t identify with the school at all (CDP 1). There was little sense that costs and benefits were fairly distributed (CDP 2) or that students had a say in decision-making (CDP 3). Behavior was poorly monitored (CDP 4), the response to rule-breaking was inconsistent (CDP 5), and conflict resolution was anything but fast and fair (CDP 6). Authority to self-govern was compromised at all levels, from the single classroom to the entire school district (CDP 7), and relations with other groups were often dysfunctional and adversarial (CDP 8). Some activities that took place within the school, such as team sports, music, drama, and after-school clubs, did a better job at implementing the CDPs, but these were the very programs that were being cut by tight school budgets and obsessive focus on meeting state standards. I knew that in some respects Katie and her friends thrived despite the Binghamton High School and not because of it. She got a civics education when she tried to fight a top-down edict about wearing hats, for example.

Against this background, the idea that we might be able to help the kids who had flunked three or more of their classes the previous year might seem like a difficult proposition. Viewed through the lens of the core design principles, however, there were reasons for hope. The Regents Academy could accommodate about sixty students. It would have its own physical location and its own small staff consisting of a principal, four teachers, and one secretary. Although the basic school curriculum would be taught and the students would be taking the statewide Regents exams at the end of the year, the design of the school was otherwise up to us. This put us in a surprisingly good position to implement the core design principles needed for any group to function well, plus two auxiliary principles that we thought were needed in an educational context.

The first auxiliary principle was the need for a safe and secure social environment. Fear is good for escaping a dangerous situation, but it is not a state of mind conducive to long-term learning. We needed to create an atmosphere that was relaxed and playful. The second auxiliary principle was the need for long-term learning objectives to be rewarding over the short term. Nobody learns much when all the costs are in the present (e.g., boring classes) and all the benefits are in the far future (e.g., getting into college). Even gifted students fail to develop their talents if they don’t enjoy what they are doing on a day-to-day basis.13

Guided by these ten design principles, we set about creating the best school that we could with the resources at hand. I was lucky to have one of my graduate students, Rick Kauffman, become involved with the project. He had experience as a public school teacher. I was also lucky that one of the four teachers, Carolyn Wilczynski, was a former student of mine and a good friend who was thoroughly at home with the application of evolutionary theory. Finally, the principal, Miriam Purdy, had a combination of passion, compassion, and strictness that was perfect for her role.

In addition to designing the school, we also designed a way to scientifically assess our results. Instead of recruiting 60 students for the Regents Academy, we identified 120 students who qualified (by flunking three or more classes the previous year) and randomly selected 60 of these to enter the program, while tracking the other 60 as they experienced the normal high school routine. This is called a randomized control trial and it is the gold standard for assessment. If the Regents Academy students did better than the comparison group, then we could say with confidence that our design principles approach was working. We also had access to information enabling us to compare both groups to the average Binghamton High School student.

It was easy to see why these students were struggling in school. In most cases, their lives out of school were woefully lacking in stability or nurturance. It seemed our task would be an uphill battle.

As we hoped, the students responded like hardy plants responding to water, sun, and nutrients. By the first marking quarter, they were performing much better than the comparison group. Definitive proof came at the end of the year when all of the students took the same state-mandated Regents exams. Not only did the Regents Academy students greatly outperform the comparison group, but they performed on a par with the average Binghamton High School student. By this metric, the deficits of years had been erased. All sex and ethnic categories posted equal gains. Everyone benefitted from the social environment that we had provided. This was only one group, but for me it was a powerful affirmation of the design principles approach.

In addition to improving academic performance, the Regents Academy rubbed off on other aspects of the students’ lives. Our students had a greater sense of individual well-being and reported a greater amount of family support than the comparison group, in part because we made a point of praising the children to their parents. Most parents receive a phone call only when their kids are in trouble, but we called to say how well they were doing. The randomized control trial assured that these differences were the result of the Regents Academy, as opposed to differences that existed prior to the Regents Academy. Our students also reported liking school not only much better than the comparison group, but also better than the average Binghamton High School student. This is an important indication that all students can benefit from the core and auxiliary design principles, not just at-risk students. After all, we had merely attempted to achieve with our meager resources what Tamar’s Quaker boarding school had achieved more comprehensively.

More about the Regents Academy is provided in the endnotes to this chapter.14 Now let’s expand the view to include the entire world of childhood education. A major theme of this book is “the theory decides what we can observe.” Most educational practices have rationales that make sense against the background of their assumptions. It is efficient to group children into classes by age. If our kids aren’t learning well enough, it makes sense to extend the school day and year and to eliminate “frills” such as recess and art. Teachers should be held strictly accountable for the learning outcomes of their students. All schools should conform to a common set of standards. No-touch rules can help to prevent physical and sexual abuse. All of these educational policies “make sense,” but somehow they add up to a public educational system that massively violates the core design principles.

Like hardy plants, Regents Academy students responded to a nurturing social environment designed with the core design principles in mind.

Evolutionary theory doesn’t just suggest new educational experiments, such as the Regents Academy. It can also be used to evaluate the vast literature on past and current educational practices, in the same way that Lin Ostrom analyzed the literature on common-pool resource groups. Consider the Good Behavior Game (GBG), a classroom management practice that was invented in the 1960s and has been extensively studied over a period of decades.15 The children in a class are asked to nominate appropriate and inappropriate behaviors, which are then displayed prominently on the classroom walls. The lists are typically much the same as what the teacher might write—even kids who act up know what it means to be good—but it makes a big difference for the students to regard the list as theirs, rather than imposed upon them. In other words, CDP 3 (decision-making by consensus or a process otherwise recognized as fair) has been satisfied rather than violated.

Next, the class is divided into a number of groups that compete to be good while doing their class work. The competition is “soft,” which means that any group can be a winner by remaining below a certain number of bad behaviors. The reward for winning can be trivial, such as picking from a prize bowl, singing a song, or even being allowed to act up for a few minutes. At first the game is played for brief periods that are announced beforehand. Gradually the duration of the game is extended and it is played unannounced until it becomes the culture of the classroom. The soft competition among groups establishes a number of the other design principles, such as a group identity (CDP 1), monitoring (CDP 4), and graduated sanctions (CDP 5). Part of the genius of the game is that the children monitor and sanction each other to make sure that their group wins the game, in addition to being monitored and sanctioned by the teacher.

Our evolutionary prediction is that all groups need the CDPs because they all need to solve the basic problems of cooperation. That goes for a class of first graders, no less than for a school for at-risk teenagers, Turkish fishers, or the lobstermen of Maine. It doesn’t matter how a group comes by the CDPs. They need not be consciously designed, and most groups certainly don’t have evolution in mind. They merely need to be implemented and a well-functioning group will result.

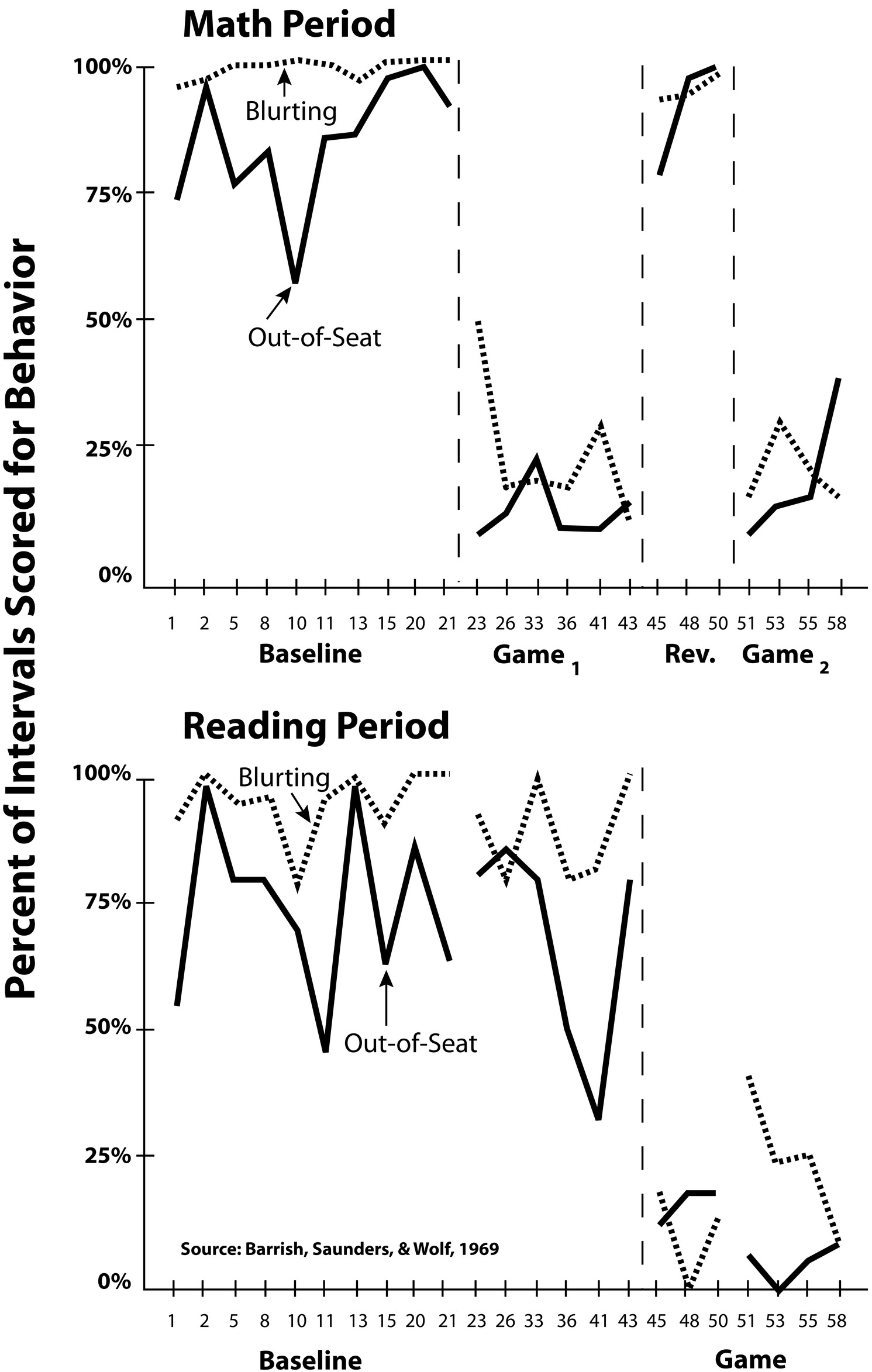

As it happens, the GBG was informed by evolution to a degree because its inventors came from the tradition of behaviorism described in the previous chapter. For the same reason, the efficacy of the game has been scientifically assessed better than almost any other classroom management technique. The figure on page 130 is from one of the first trials published in 1969.16 Adult observers in the classroom monitored two bad behaviors that could be easily measured: “out of seat” and “blurting.” During the baseline period (time interval 1–21), the class was essentially in chaos with these behaviors being expressed between 75 percent and 100 percent of the time. When the GBG was played during the math period but not the reading period (time interval 22–44), the bad behaviors plummeted for the former but not the latter. Then the GBG was played during the reading period but not the math period (time interval 44–50), and the expression of bad behaviors flipped. Finally, when the GBG was played during both the math and reading periods (time interval 51–58), the students were well behaved in both cases. This is a good example of how scientific methods can be employed in real-world situations. Is any more proof needed that the GBG “turned on” good behavior in this particular classroom?

The Good Behavior Game “turns on” good behavior almost as easily as turning on a light.

Unsurprisingly, a lot more learning takes place in classrooms where this technique has been implemented. More surprising is the lifetime benefits for the students. For this result we have a randomized control trial to thank that dwarfs my effort with the Regents Academy. In the 1980s, Shep Kellam, a psychiatrist at the Johns Hopkins University, persuaded the Baltimore City School District to randomly assign first- and second-grade teachers to classrooms and then to randomly assign the classrooms to one of three conditions: the GBG, another evidence-based teaching strategy called mastery learning, or no special intervention.17 A total of 1,240 African-American students participated in the study and those who were assigned to the experimental group spent only one year in a GBG classroom (i.e., either the first or second grade but not both). The scope of this randomized control trial is impressive. Even more impressive, Kellam and his team of researchers continued to track the students into their adulthood. In fact, the study is still in progress with the participants in their midthirties.

In the two control conditions (mastery learning and no special intervention), some teachers were able to keep their class under control, but chaos reigned in the other classrooms. What good is a pedagogical method such as mastery learning when no learning of any kind is taking place? In the classes that played the GBG, the students were on task and cooperative, as expected from previous research in different locations.

You might think that the beneficial effects of the GBG would evaporate when the students went on to other classes that did not play the game. Instead, the kids built upon the social skills that they acquired during that single year. By the sixth grade, the GBG kids were less likely to face arrest or become smokers. As young adults, they were more likely to be in college or gainfully employed, less likely to be incarcerated or addicted to drugs, and less likely to commit suicide. An economic analysis conducted by an independent party estimated that for every dollar spent on the GBG, eighty-four dollars were saved through reduced special education, health care, and criminal justice costs.

An 84-to-1 benefit/cost ratio is mighty impressive. You might think that the use of the method would spread rapidly on the strength of such evidence. As it happens, the GBG is spreading worldwide,18 but not nearly as fast as you might expect. After all, it has now been over fifty years since the game was invented. In the meantime, other educational practices have spread that flagrantly violate the core design principles because they “make sense” on the basis of other rationales. There is no evidence that modern education as a whole is gravitating toward the core design principles and no reason to expect it to, until it is viewed through the lens of the right theory. Now let’s train the same lens on another kind of group.

NEIGHBORHOODS

A neighborhood is a group of people living in close proximity to each other. Neighborhoods are less important than they used to be, since it is so easy to travel beyond their boundaries, but they are still very important for child development and a high quality of adult life.19 We know from common experience that neighborhoods vary greatly in quality, but how much of this variation can be explained by the presence and absence of the core design principles? I invite you to reflect upon this question for the neighborhoods in your own life.

One of Lin’s former PhD students, Roy Oakerson, and his own student, Jer Clifton, made a study of a neighborhood association in Buffalo, New York, that was doing an excellent job implementing the CDPs.20 Located in a run-down section of Buffalo’s West Side, the West Side Community Collaborative (WSCC) began by creating small units called block clubs, where residents of a single block could meet regularly, enjoy each other’s company, and accomplish manageable goals such as cleaning up vacant lots and putting in gardens. Residents identified more strongly with their block clubs than with the WSCC or the city as a whole (CDP 1). Being organized into small units meant that block club members benefitted from their own efforts (CDP 2). True, residents of a given block who did not join the club also benefitted to a degree, but they also became the target of sanctioning if they were part of the problem, such as being the owner of a derelict property. Consensus decision-making was spontaneous in very small groups that met regularly (CDP 3). The block clubs could monitor compliance with building codes much more closely than city code officers (CDP 4). When dealing with the owner of a derelict property, block club members began with friendly persuasion, but if that didn’t work then city inspectors were called in (CDP 5). Mild disagreements could be discussed and settled during block club meetings or on the block. More serious disagreements could be discussed in Housing Court, which provided an independent, authoritative third party for conflict resolution (CDP 6). The block clubs were officially recognized by the City Hall’s Board of Block Clubs and were free to manage their own affairs as long as they followed the general rules for frequency of meetings, election of leaders, and adoption of bylaws (CDP 7). The relationships between the block clubs and other groups, such as the WSCC and various branches of the Buffalo city government, were primarily helpful (CDP 8). Indeed, the block clubs required a larger scale of social organization (Housing Courts, code officers, and City Hall) to implement critical features of the core design principles such as graduated sanctions and conflict resolution.

I have toured the WSCC neighborhoods with Roy Oakerson and was inspired by them. There was not a randomized control trial in this case, but the brightly colored houses and profusion of flower gardens offered their own kind of proof. These neighborhoods had improved, not by an influx of money from outside the community, but by the residents empowering themselves with assistance from the city at strategically chosen moments.

Turning to the academic literature on neighborhoods, if you read classic books such as Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities or Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone,21 the core design principles leap out of almost every page. Outstanding research led by the Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson has identified collective efficacy—the ability of residents to monitor and informally police their neighborhoods (CDPs 4 and 5)—as one of the strongest predictors of neighborhood success. It is likely that a systematic review will provide strong support for all of the CDPs. Yet this does not mean that the CDPs are obvious to everyone or that more and more neighborhoods are using them over time. On the contrary, Jacobs and Putnam wrote their books because the trends were going the other way. Efforts to “develop” cities were tearing neighborhoods apart, and group activities of all sorts were becoming much less frequent than during our parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Thus, there is tremendous opportunity for both academic investigation and practical improvement of real-world neighborhoods by adopting the CDP approach.

Notice that in all of my examples so far, the core design principles are both old and new, familiar and ignored. They are adopted by some groups but not others and showcased by some academic schools of thought but not others. Major figures such as Lin Ostrom or Robert Putnam are famous within their academic circles but otherwise largely unknown, as we saw with Lin’s invisibility to the economics profession. One of the main contributions of evolutionary theory is to establish the generality of the CDPs as fundamental to all cooperative endeavors and therefore to predict that they are needed by all groups whose members must cooperate to achieve shared goals. This bold prediction goes beyond any previous school of thought that already recognizes the importance of the core design principles within a smaller domain. Now let’s see if our prediction holds for another kind of group: religious congregations.

RELIGIOUS GROUPS

If you had a religious upbringing, you might regard your congregation as among the most important groups in your life. Or you might have left your congregation behind as soon as you were able to act upon your own decisions. Religious congregations vary in how well they function for their members. Can their success or failure be explained on the basis of the same CDPs that work for common-pool resource groups, schools, and neighborhoods?

Religions would not persist if they didn’t provide something for the average believer on a day-to-day basis.22 That “something” includes a sense of meaning provided by a relationship with the divine and a supportive community of people united by the religion. These two things are closely connected. One’s relationship with the divine informs one’s relationships with other people. As a gospel song puts it, “If you don’t love your neighbor, then you don’t love God.”

So a religion can do a great job creating a strong group identity and sense of purpose, which is the first CDP, but that’s not enough. A religious group is faced with the same challenges as any other kind of group—a distribution of costs and benefits, decisions to be made, rules to be monitored and enforced, conflicts to be resolved, and relationships with other groups to be negotiated. If a religious group can’t do these things well, then it will fall apart or be abandoned by its members for some other kind of group, which might be religious or secular.

This kind of competition is taking place all around us. My city of Binghamton includes approximately a hundred active religious congregations. Some are growing while others are shrinking. Many have folded altogether. Others are colonizing the area from elsewhere and even being invented de novo. Two major religious denominations, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Seventh-day Adventists, originated in little towns in New York State during the nineteenth century and now have millions of adherents worldwide. Christianity and Islam, which each have billions of adherents, had the same kind of humble origins. In short, religions are great bushy trees that evolved, and continue to evolve, by cultural evolution.

The origin of Calvinism, which emerged in the city of Geneva during the Protestant Reformation, provides a great example of how the core design principles contributed to its survival and spread.23 Although John Calvin (1509–1564) is sometimes portrayed as a religious dictator, the Ecclesiastical Ordinances that he drafted in 1541 were strongly egalitarian (CDP 3). The head of the church was not Calvin but a group of twelve pastors (including Calvin) who functioned as equals. When they couldn’t agree, the decision-making circle was widened, not narrowed (CDP 6). The duty of attending to dying plague victims provides an example of how the pastors solved problems in a fair manner using mechanisms that were difficult to subvert (CDP 2). This life-threatening task was decided by lottery. Calvin was exempted from the lottery by a group decision because his death would have had a greater negative impact on the fate of the church than the death of another pastor. Thus, Calvin was recognized as a leader, but he did not have the authority to exempt himself from the lottery.

The city of Geneva was too large for everyone to know each other (although it was a mere town by modern standards) so it was divided into sectors. Each sector was overseen by an elder, whose role was to “have oversight over the life of everyone (CDP 4), to admonish amicably those whom they see to be erring or to be living a disordered life, and, where it is required, to enjoin fraternal corrections themselves and along with others (CDP 5).” Crucially, elders had to be accepted by the people being overseen (CDP 3), as well as by the church leaders and the city government (CDP 8). No wonder that the city functioned so much better after the implementation of these rules! Geneva became known as “the City on the Hill” and its social organization was widely admired and copied by other Protestant reformers.

The need to divide Geneva into smaller sectors illustrates one of the major themes of this chapter: the small group as a fundamental unit of human social organization. Living in small groups has been baked into our psyches by thousands of generations of genetic evolution, and small groups need to remain “cells” in the cultural evolution of larger-scale societies. One of the newest products of religious cultural evolution, the “cell ministry,” illustrates the same principle. It was invented by a Korean evangelical pastor, Dr. David Yonggi Cho (he would say that it came from God), who was trying to grow his congregation and had come to the limits of his own time and effort.24 He decided to create “cells,” small groups that meet in people’s homes in addition to attending the large church services. The result was so successful that his Yoido Full Gospel Church became the largest in the world, with over 730,000 members organized into more than 25,000 cell groups—a veritable multicellular organism!

Dr. Cho is a creationist, but his writing is full of biological metaphors and dovetails perfectly with an evolutionary worldview. The main power of a cell is its small size, which enables members to know each other on a face-to-face basis, just as our ancestors did in their small groups throughout our history as a species. This is in contrast to even a moderate-size church congregation, which is too large for such personal interactions. Dr. Cho has decided that fifteen families are an optimal size for a cell group. When a cell becomes larger than this, it is instructed to split.

Cell group members regard each other as family and provide the same kind of material benefits that friends and family members provide for each other, including help with the daily round of life and support during difficult times such as illness, marital problems, or losing one’s job. Cell group members also provide important social and psychological benefits to each other. Dr. Cho identifies physical touching, recognition for the role that one plays, praise for exceptional contributions, and love as the most important ingredients that cell groups are exceptionally good at providing. They are also excellent for monitoring commitment to the group and conformance to agreed-upon behaviors (CDP 4). If someone doesn’t attend a large church service, nothing is done about it. If someone doesn’t attend a cell group meeting, there is an immediate effort to find out why and extend help if necessary.

Also, cell groups are excellent for recruiting new members. This is a good example of an auxiliary design principle, needed by some groups and not others. For most of our evolutionary history as a species, we lived in culturally homogeneous groups that did not recruit new members from other cultures. Judaism for most of its history is an example of such a cultural religious tradition. An evangelizing religion such as Christianity and Islam was a cultural innovation that changed the course of world history, creating strong and unified groups that grow not only by biological reproduction (they tend to do a good job at that too) but also by converting adults from other faiths. Today, in the modern landscape of religion, an auxiliary design principle such as the need to evangelize is as important as the core design principles. Cell groups can recruit new members from their immediate vicinity such as their neighborhoods, apartment buildings, and businesses, which is far more effective than revival meetings or knocking on doors. Some cell group leaders are so zealous that they ride up and down the elevators of their apartment complexes in an effort to recruit new members. Just as Calvinism was widely copied during the Protestant Reformation, cell group ministries have spread around the world, including some of the religious congregations in Binghamton. One Internet meme shows a smiley face surrounded by the hexagonal array of a honeycomb with the words “What the cell is to the body…the small group is to the church.” If only religious believers knew how much their biological metaphors can be affirmed by current evolutionary science!

To summarize, our prediction that all groups need the CDPs can be extended to religious congregations, in addition to common-pool resource groups, schools, and neighborhoods. How about our workplaces?

BUSINESS GROUPS

A business, or firm, is a group of people with the shared endeavor of manufacturing a product or providing a service. It goes without saying that members of a business group must cooperate to accomplish their goals. In addition, between-group competition is fiercer in the business world than in most other walks of life. It therefore stands to reason that if the CDPs are required for groups to function well, they should have become standard business practice in the same way that they have become standard religious practice.

Yet this is very far from the truth. Instead, there is a widespread perception that the game of business hardball is played by a different set of rules, symbolized by the fictional character Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street. Greed is good, your value to society is measured by your wealth, and the only responsibility of a business is to maximize profits for its shareholders. Conventional morality isn’t needed because the invisible hand of the market ensures that everything will come out right.

This worldview has become so pervasive that we have grown accustomed to it, as if it must be true, no matter how much we might wish otherwise. In reality, it is a very idiosyncratic view that has its roots in the nineteenth century but didn’t become prominent until the mid-twentieth century. It is based on the particular form of reductionism known as Homo economicus, which imagines people as entirely self-regarding agents operating in a frictionless market.25 Here is how the economist Herbert Gintis describes the influence of Homo economicus on the business world:

After World War II, business schools blossomed all over the United States. All the major universities set up business schools. Before that, businessmen were just businessmen. They didn’t go to college, or if they did they didn’t learn anything about business. But these new business schools were very professional. When they wanted to teach economics, they simply borrowed from the economics discipline. In economics it’s called Homo economicus. Homo economicus is not that popular any more but it certainly was after World War II. Homo economicus has no emotions. He’s totally interested in maximizing his wealth and income. He really doesn’t care about other people, although he does care about leisure. Leisure, income, and wealth are the only things. When they taught this to business school students it obviously followed that if you’re a good businessman you should just maximize your material wealth. This is greedy. Being greedy is human, it’s good to do, and the more greedy you are the more successful you’ll be.26

It would be hard to imagine a more consequential case of the theory deciding what we can observe. If economists say that personal greed is the way to do business, then so it must be. Just as many educational practices that make sense against the background of their assumptions end up being disastrous for our kids, business practices that make sense against the background of Homo economicus end up being disastrous for our businesses and economies. That, at least, is the prediction that emerges from multilevel selection theory.

Fortunately, no matter how much the business community has been blinded by the Homo economicus worldview, there is a large academic literature on business performance that can be analyzed in the same way that Lin Ostrom analyzed the literature on common-pool resource groups. Once we employ the right theory, we can see that the game of business hardball is no different from any other game requiring cooperation to accomplish shared goals. Here are some highlights.27

In his book The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First,28 the Stanford Business School professor Jeffrey Pfeffer amasses a mountain of evidence that businesses can be profitable by taking good care of their employees (CDP 2). One study reported by Pfeffer followed the fate of 136 companies over a five-year period, starting from the time that they initiated their public offering on the U.S. stock market. The management practices of the companies were coded using information from their offering prospectuses, which were publicly available. Statistically controlling for other factors, companies that placed a high value on human resources and sharing profits with employees had a much higher survival rate over the five-year period than companies that treated their employees as expendable.29 This provides solid evidence that companies depend upon CDP 2 for their very survival.

Multilevel selection theory predicts that firms lacking the CDPs will become crippled by the disruptive self-serving strategies of employees and subunits within the organization. The sociologist Robert Jackall provides a detailed ethnography of a crippled firm in his book Moral Mazes: The World of Corporate Managers, which was published in 1988 and reissued in 2009 because of its relevance to the Great Recession.30 As the jacket description puts it: “Robert Jackall takes the reader inside a topsy-turvy world where hard work does not necessarily lead to success, but sharp talk, self-promotion, powerful patrons, and sheer luck might.” In this unprotected social environment, employees with higher ethical standards are either washed out of the system or learn to change their ways. Fortunately, this is not a statement about all corporations but only corporations lacking in the CDPs. As New York University’s Stern Business School professor Jonathan Haidt has stressed, the entire system must be ethical for individuals to be ethical within the system.31 The way to create an ethical system is to implement the CDPs.

In his 2013 book Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Business School professor Adam Grant identifies three broad social strategies—giving, matching, and taking.32 Givers freely help others, matchers give only when they expect to get, and takers try to get without giving whenever possible. The “greed is good” mentality suggests that givers can’t possibly survive in the business world. Grant blends authoritative studies with entertaining biographies to show that givers do the best and the worst. They are spectacularly successful when they manage to combine forces with other givers, but they become chumps and doormats when surrounded by takers—exactly as expected from multilevel selection theory. A company that implements the CDPs is likely to become a mecca for giving, while taking is likely to accumulate in companies that lack the CDPs.

A 2012 British government report documented that employee-owned companies compared very favorably with conventional companies, especially during the 2008–2009 economic downturn.33 Advantages of employee-owned companies include a higher degree of engagement and commitment, greater psychological well-being, and lower staff turnover, all of which make sense in terms of the CDPs. The report also identified barriers to employee ownership. These included (a) lack of awareness of the very concept; (b) lack of resources available to support employee ownership; and (c) legal, tax, and other regulatory barriers to employee ownership. In other words, employee-owned companies thrive even in a business environment that is stacked against them. How well would they do in a business environment that was stacked in their favor?

There are numerous movements to make corporations more socially responsible. One of these is B Lab (B stands for Benefit), which has established itself as a certifying organization, similar to the LEED certification for buildings.34 Companies submit information to B Lab on their social responsibility practices in four areas: governance, workers, community, and environment. B Lab calculates a score based on this information. If it is high enough, then the company can advertise itself as a B Corp. Over 2,000 companies from over fifty nations have become B Corps, including household names such as Etsy and Patagonia. Conventional business wisdom suggests that every dollar spent on social responsibility is a dollar taken away from the bottom line. If this were true, then B Corps should be losers in the marketplace, much as we might wish otherwise. But it’s not true. A 2014 study by Thomas F. Kelly and Xuijian Chen shows that B Corps are as profitable or more profitable than a matched sample of conventional businesses.35

Tom and Xuijian (known as Jerry to his American friends) happen to be on the faculty of my university’s School of Management, providing an opportunity for me to team up with them and engage one of my graduate students, Mel Philips, to study B Corps in more detail. With the help of B Lab CEO Jay Coen Gilbert, we made site visits to five B Corps in the New York City area, where we met separately with the CEOs and groups of employees.

I must confess that before the site visits, even I was brainwashed into thinking that a genuine commitment to socially responsible goals must handicap a company in its struggle for existence against other companies. Only after talking with the employees and CEOs did I fully appreciate how B Corps became stronger, not weaker, by looking beyond their short-term profit statements. Employees were proud and often passionate about their work (CDP 1) as opposed to regarding it as “just a job.” They felt that they were financially and socially recognized for their contributions and benefitted from policies such as good health care, the ability to work at home, parental leave, and participation in communitarian activities while on the job, which enabled them to achieve a work-life balance (CDP 2). They were often included in making important company decisions (CDP 3). One reason that CEOs valued the B Corp certification process was not only to advertise their commitment to social responsibility, but also to monitor their company’s performance in each of the four areas (CDP 4). Their commitment to employee welfare led to humane policies for enforcing agreed-upon behaviors (CDP 5), resolving conflicts (CDP 6), and giving employees elbow room in how they did their jobs (CDP 7). Finally, the companies were joining forces with other like-minded agents of the larger economic ecosystem—suppliers, customers, shareholders, competitors, and regulatory agencies—to implement the same principles at a larger scale (CDP 8), a point to which I will return in the chapter on multicellular society.

These policies are no more difficult to implement by a business corporation than any other policy—for example, a review of practices that can increase the four components of the B score, becoming inclusive about making major decisions, or implementing a work-at-home policy in which the effects on productivity are appropriately monitored. It is mostly a matter of seeing that they make sense, figuring out the best implementations, and monitoring the results. By the time we returned from our final site visit, I was personally convinced that the CDPs are needed by business groups as much as by any other kind of group. Blindness to this fact has resulted in tremendous harm at all scales, from exploited workers to an unstable worldwide economy and collateral damage to the environment. That’s the bad news. The good news is the room for improvement when we view the business world through the lens of the right theory.

FROM GROUPS TO INDIVIDUALS AND THE WORLD

The bold prediction of multilevel selection theory is that all groups requiring cooperation to achieve shared goals need the same core design principles. Whether this was already obvious to you depends on how you were looking at it, either informally on the basis of your experience, or through the lens of a more formal worldview such as orthodox economic theory. As we have seen repeatedly, nothing is obvious all by itself. For every worldview that makes the CDPs appear sensible, there are others that make them appear wrongheaded or downright invisible. Hence, it is an accomplishment to establish the generality of the CDPs by showing that they follow from the evolutionary dynamics of cooperation in all species and our own history as a highly cooperative species, mostly at the scale of small groups.

No theory leads directly to the right answer, which is why predictions must be put to the test with information from the real world. Testing the prediction that what Lin showed for common-pool resource groups also holds for all other kinds of groups will occupy scholars and scientists for decades to come. My current assessment, based on my own research and review of the literature, is that the prediction is strongly supported.

But please don’t wait for the experts. You can start thinking about the CDPs for the groups in your life right away. Use your own judgment and if you think that a given group can do a better job implementing the CDPs and appropriate ADPs, give it a try and see what happens. Of course, this must be done in collaboration with other members, since acting unilaterally would itself be a violation of the principles. If you would like some assistance implementing the CDPs and monitoring the results of your efforts, then visit www.prosocial.world, where you can learn more on your own and engage with a trained facilitator if you like. I will say more about this worldwide framework for working with groups in the final chapter. For now, it is important to show how strengthening your groups can help you to thrive as an individual and have a greater impact on the larger world.