8

From Groups to Multicellular Society

The human population on earth is approximately 7.6 billion individuals. These people are divided into nearly two hundred nations that are highly variable in how well they govern their affairs. Governance at the transnational scale (for example, NATO, the United Nations, the European Union) is extremely weak and nations are competing with giant corporations for global influence. Together with our domestic plants and animals, we are rapidly crowding out the rest of nature. Our collective impact on the planet and its atmosphere has given rise to the term “anthropocene,” a new geological age.1 Scientific estimates of global warming have been too conservative. The earth is heating even faster than we feared it would. Yet many of our decision-makers are still in denial, and even those who accept the grim truth don’t know what to do about it.

It is easy to conclude that the problems confronting us at the global scale are too large and complex to be solved, no matter what our theoretical perspective. But perceptions of size and complexity can be deceiving. Recall from past chapters that our bodies are composed of trillions of cells with billions being renewed daily, which serve as planets for a diverse ecosystem of thousands of other species. Yet, despite these huge numbers and complex interactions that we have only begun to fathom, our bodies, at least in health, function with a precision that puts a Swiss watch to shame.

Or consider that roughly ten thousand years ago, there were no large-scale human societies, only tribes of a few thousand individuals. Something happened in a wink of geological time that resulted in nations numbering in the millions and even billions of individuals. Transnational governance might be weak, but it would have been inconceivable two centuries ago. Compared to where we started ten thousand years ago, well-functioning governance at the scale of the whole earth seems just within reach.2

A single body is the gold standard for a well-functioning human society, as English words such as “corporation” that are derived from the Latin word for “body” (corpus) attest. Human societies have been metaphorically compared to single bodies since antiquity, from Aristotle’s Politics to Hobbes’s Leviathan, but only now has it become possible to place the metaphor on a firm scientific foundation. The first step toward viewing the whole planet as a single organism is to challenge the current orthodoxy and adopt the right theory.

THE INVISIBLE HAND IS DEAD

Arguably the most important concept in economics, from the origin of the profession to the present, is laissez-faire, which means “let it alone” in French.3 The first known appearance of the phrase in print was in 1751, and the context was exactly the same as when the phrase is used today—to argue against government restrictions on trade. At that time, government was absolute monarchist rule and Christianity was the unquestioned worldview. It made sense to argue that there was a natural order, that governments were disrupting the natural order, and that the solution was to return to the natural order by letting things alone with respect to the economy.

Other milestones in the history of the laissez-faire concept were Bernard Mandeville’s (1670–1733) Fable of the Bees, which fancifully compared human society to a beehive whose members are motivated entirely by greed,4 and Adam Smith’s (1723–1790) metaphor of an invisible hand, which guides selfish interests toward socially beneficial ends.5 These expressions differed from each other. Conventional religious thinkers were scandalized by The Fable of the Bees, and Smith was not an admirer of Mandeville. However, all expressions of the laissez-faire concept relied upon the concept of a natural order—a system that works well as a system, with each element unknowingly doing its part. Without the concept of a natural order, there can be no justification for the prescription to let it alone.

The next milestone in the history of the laissez-faire concept was the French economist Léon Walras (1834–1910), who was inspired by the emerging science of physics to create a “physics of social behavior.” It is easy to appreciate the allure of this goal. Isaac Newton and others had created mathematical equations that predicted such things as the motion of planets with astonishing accuracy. Wouldn’t it be amazing to derive a comparable set of equations for economic systems? Walras and others succeeded at this goal, but only by making lots of simplifying assumptions about the preferences and abilities of individuals and the social environment in which economic transactions take place. Their work became the foundation for the school of economic thought that today is variously (and confusingly) called “orthodox,” “neoclassical,” and “neoliberal.” The bundle of assumptions about human nature that is required for the mathematical equations to work is often called Homo economicus, as if it were a biological species.

All of this is pre-Darwinian. As we saw in chapter 4, Darwin’s theory challenged the concept of a natural order, which made it profoundly disturbing to the Christian worldview. Even Darwin took a long time to realize this implication of his own theory. At first, he thought that his principle of natural selection could explain all of the design in nature that had been attributed to a creator. Gradually it dawned upon him that his theory could only explain functional design at the level of individual organisms. Morally praiseworthy traits such as honesty, bravery, and charity are selectively disadvantageous, compared to more self-serving traits within the same group. The same evolutionary process that created functional order at the level of the individual created functional disorder at the level of a social group. Darwin solved the problem to a degree by developing the concept of between-group selection, but that only notches functional design a little higher up the scale of nature—a war of groups against groups, rather than a war of individuals against individuals within groups.

Few people realize the degree to which the modern economics profession rests upon a pre-Darwinian foundation. The very concept of a “physics of social behavior” is misconceived, no matter how alluring it was at the time. No amount of tinkering with the assumptions of Homo economicus can save the mathematical edifice that seems to give the economics profession such authority. The first steps taken in a Darwinian direction by figures such as Joseph Schumpeter and Friedrich Hayek and their followers are only the beginning, and the inferences drawn from them are often mistaken. The field of behavioral economics, which challenges orthodox economics on empirical grounds, is still far from adopting Tinbergen’s fully rounded four-question approach. In short, the concept of laissez-faire as we know it is dead as far as scientific justification is concerned, no matter how much it continues to influence political and economic policy.

LONG LIVE THE INVISIBLE HAND

In the days of absolute monarchs, the death of one and coronation of the next was sometimes announced with the words “The King Is Dead! Long Live the King!” In this spirit, I’m happy to herald a new concept of laissez-faire that can be justified by evolutionary theory. All that’s needed is to replace the concept of a natural order with the concept of a unit of selection.6

If by laissez-faire we mean a society that functions well without members of the society having its interest in mind, then nature is replete with examples. Take the fabled bees that Mandeville chose to compare with human society. He was right that a bee colony functions well as a unit. He was also right that individual bees don’t have the welfare of their colony in mind. After all, bees don’t even have minds in the human sense of the word. But Mandeville was hilariously wrong to portray individual bees as like selfish human knaves. Instead, individual bees take part in the economy of the hive in the same way that individual neurons take place in the economy of the brain.

For example, when foragers return with their load of nectar and pollen, they are genetically programmed to dance in a way that conveys information about the location of the flower patch that they visited, with the length of the dance proportional to the quality of the patch. Other workers are programmed to pick a dancing bee at random and go where she went. The fact that some dances are longer than others introduces a statistical bias, directing more bees to the best patches without any bee making a decision. In this fashion, little snippets of behaviors by individual bees combine to make the colony function well as a unit. But there are any number of other behaviors that would not be good for the colony. Luckily, those negative behaviors were left on the cutting-room floor of natural selection. In other words, colonies whose members responded to the cues of their local environments in the right way survived and reproduced better than colonies whose members responded to the cues of their local environments in the wrong way. The result is an outstanding example of laissez-faire—a society that functions well without members of the society having its welfare in mind. It would never have happened without colony-level selection. Colony-level selection is the invisible hand that promotes the individual-level behaviors that benefit the common good rather than the much larger set of individual-level behaviors that would harm the common good.

The same story can be told for the genes, cells, and organs of multicellular organisms, which are the gold standard for a well-functioning society. To call a multicellular organism a society of lower-level elements is no longer metaphorical. It is literally the case that we are groups of groups of groups and that we qualify as organisms only because of our degree of functional organization, which evolved by between-organism selection. Also, a close look reveals that the ideal organism does not exist. Even the gold standard is marred with impurities that we can clearly recognize in human terms as disruptive self-serving behaviors at the level of cellular and genetic interactions, such as the example of cancer recounted in chapter 4.

RETHINKING REGULATION

As soon as we replace the concept of a natural order with the concept of a unit of selection, then the concept of regulation appears in a new light. Try to forget how politicians and economists talk about regulation and focus on how biologists talk about it. To regulate something means keeping it within certain boundaries—not too high or too low. The temperature in your home is regulated by a thermostat, a heating device such as a furnace, and a cooling device such as an air conditioner. The thermostat monitors the temperature and turns on the furnace or air conditioner, depending upon which is required to keep the temperature within bounds.

The number of processes in your body that need to be regulated to keep you alive is mind-boggling. Your temperature. The levels of glucose and CO2 in your blood. Your blood pressure. Your sleep cycle. Your emotions. The list goes on and on. Each process has the equivalent of a thermostat, heater, and cooler. All of them have been provided to you by the process of between-organism selection, which favors the regulatory processes that work over processes that work less well or not at all.

In the bee colony, regulatory processes have been notched upward to include the social interactions among the bees in a colony. Social insect biologists even call these interactions “social physiology” to emphasize that they are orchestrated for the good of the colony as a whole. Take temperature regulation as an example. When the temperature in a beehive becomes too low, some workers start to vibrate their muscles to generate heat, just as we do when we shiver. When the temperature becomes too high, some workers fly away to collect water and return to spread it over the colony, in the same way that we sweat. The list of social regulatory processes in beehives and other social insect colonies goes on and on, like the list of physiological regulatory processes operating within each of us. A colony without regulation is a dead colony.

If human groups are to function like organisms, then they need to be regulated in the same way. What is the social physiology of small human groups that keeps our behaviors within bounds in the service of collective goals? And how have these regulatory mechanisms been scaled up during the last ten thousand years of human cultural evolution?

MY HALL OF SHAME

A trivial event in my own life illustrates the social physiology of small human groups. One day when my kids were small I decided to take them bowling. I seldom bowl, so I had forgotten that if someone in the lane next to you is about to bowl, it is customary to wait until they have finished before you take your turn. After violating this norm several times, an employee of the bowling alley discreetly and politely informed me about the right way. There could not be a more trivial incident, but my sense of shame was overpowering! I was physically incapacitated and left the bowling alley with my children as soon as I possibly could.

Here is another trivial episode from my personal Hall of Shame. When one of my kids started taking karate lessons, I decided to join her rather than just sitting on the sidelines waiting for the sessions to end like the other parents did. I soon became fascinated by the martial arts dojo. Several dozen people on the floor were managed by our single sensei, like the conductor of an orchestra. People paired up to perform the katas or to spar in a way that did not result in physical injury. Each person functioned as either a student or a teacher, depending upon how their skill level compared to that of their partner. Transitions from one activity to another were accomplished swiftly with rituals such as bowing. In this fashion, an extremely complex body of knowledge was being transmitted from one person to another.

At the end of each session, everyone lined up in front of the sensei to learn if they had graduated to the next skill level, symbolized by the coveted belt colors. If your name was called, you advanced to face the sensei, bowed, and stood on his left side to receive your new belt with a round of applause. When I earned my yellow belt, I thoughtlessly stood on his right side. Once again, I was sweetly shown the right way without any animosity, but I remember the shame burning in my ears to this day.

I know that I am not alone in my sensitivity to keeping in step with others in the dance of human life. It is part of what makes us human. We scarcely notice it most of the time because we are so practiced in our everyday lives. We have all earned our black belts in that regard. However, if you’re like me, then as soon as you try to do something new within your own culture or visit another culture, you become acutely aware of the need to keep in step.

Nobody taught us to feel and act in this way. It is part of the psychological equipment issued to us by genetic evolution, based on thousands of generations of living in small groups.7 Those who didn’t care about abiding by norms did not prevail in the competition for survival. Either they failed within their groups because of a negative reaction on the part of other group members, or their entire groups failed for lack of a coordinated response to life’s problems.

Life’s problems are highly contingent. If you’re an Inuit living in the Arctic, you need to coordinate your behavior in a different way than if you’re an Mbuti living in the African equatorial jungle. Our basic psychological equipment is not learned and is roughly the same the world around, but it enables us to learn, regulate, and transmit the enormously complex body of knowledge that is required to survive and reproduce in any particular time and place. You can’t have the learned knowledge without the genetically evolved psychological equipment.

To summarize, regulation, as biologists use the word, is needed to coordinate our lives in small human groups, just as much as it is needed for bodies and beehives. One more point needs to be made before we begin scaling up to larger human societies and ultimately the whole planet. Bodies and beehives provide outstanding examples of the invisible hand because they function well even though lower-level units don’t have the whole’s interest in mind. We know this for sure because genes, cells, and bees don’t have minds in the human sense of the word. When we begin thinking about small human groups as units of selection in genetic evolution, we introduce the possibility that the lower-level units (individuals) could consciously behave to benefit the welfare of the higher-level unit (their group) because they do have minds. This is not required—people could be like genes, cells, and bees in this regard—but neither is it prohibited. It is easy to imagine a group whose members care only about the personal advantages that come with a good reputation and not the group as a whole. And such a group could work well if a good reputation requires behaving as a solid citizen. It is equally easy to imagine a group whose members do care about everyone’s welfare and not just their own reputations. And this group could also work well. Which type of group is most likely to result from a process of between-group selection? This is a question about the mechanisms that underlie group-level performance (Tinbergen’s mechanism question). If the mechanisms are functionally equivalent, what evolves might be a matter of historical contingency, like the different populations of E. coli that evolved to digest glucose in different ways (Tinbergen’s history question). Once an evolutionary worldview has become part of your intuition, then this interplay of Tinbergen’s four questions will be like second nature for you.

SCALING UP

Our capacity for rapid adaptation eventually led to a positive feedback loop in which the ability to produce food increased the size of human groups, which in turn enhanced the ability to produce more food. Paleoanthropology, archaeology, and recorded history provide a fossil record of this cultural evolutionary process. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of historians have concentrated primarily on the history question and paid scant attention to Tinbergen’s other three questions. An exception is the Harvard historian Daniel Lord Smail. In his book On Deep History and the Brain, Smail points out that most world histories begin about 4000 BC in the Middle East, which is suspiciously close to the time and location of the Garden of Eden according to biblical accounts.8 Most historians are not young earth creationists, of course, so shouldn’t they be extending their field of inquiry deeper in time and more widely in space? Shouldn’t they also know something about the brain as a product of genetic evolution, which determines how people act at all times and places in a mechanistic sense?

The person who has advanced this agenda more than any other is not a historian but a biologist named Peter Turchin, son of the Russian physicist and dissident Valentine Turchin.9 Peter immigrated to America with his father in 1978 and became a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, specializing in population dynamics. Many species in nature fluctuate in their numbers, with booms and busts that sometimes take the form of regular cycles and at other times are more chaotic. These fluctuations reflect complex interactions with other species in the community, along with exogenous factors such as climate. Using a combination of theoretical models and statistical tools for analyzing time series data, population biologists have become adept at explaining the booms and busts of species such as lemmings and bark beetles. Peter was among the best but when he reached midlife he decided that he needed a new challenge. He would apply his theoretical and statistical skills to the study of human history.

In a single stroke, Peter had isolated himself from almost everyone at his university and the wider world of academia. His colleagues in the Department of Ecology and Evolution never dreamt of studying human history and those in other departments who studied human history never dreamt of employing his theoretical and statistical toolkit. Indeed, so many attempts at grand historical narratives have come and gone (such as Marxism) that many historians have given up on the possibility of a unifying theoretical framework.

Undeterred, Peter announced the birth of a new field: cliodynamics, which combines the name of Clio, the muse of history in Greek mythology, with “dynamics,” the study of how things change over time. That was fifteen years ago, and by now Peter’s vision has fulfilled itself to a considerable degree. Thanks to him and a growing number of colleagues, we can begin to understand how cultural evolution favored ever-larger societies over the last ten thousand years, leading to the mega-societies of today. We can also zoom in on the United States of America as a boom-and-bust society, with periods of harmony that alternate with periods of discord over its 250-year history. Only when we understand history as part of evolution can we go beyond past efforts to improve national governance and work toward regulating our activities at a planetary scale.

THE LAST TEN THOUSAND YEARS

According to Peter’s analysis, cultural evolution is a multilevel process much like genetic evolution. A learned behavior can spread through a population by benefitting individuals compared to other individuals in the same group, or by benefitting the whole group compared to other groups in the vicinity.10 A learned behavior can even hop from head to head like a disease, at the expense of both individuals and groups, a possibility popularized by Richard Dawkins under the name “parasitic meme.”11

The regulatory mechanisms that operate in small human groups are pretty good at weeding out learned behaviors that are parasitic or benefit some individuals at the expense of others within the same group. However, these mechanisms were not designed to work on a larger scale. The first agricultural societies therefore became despotic, ironically more like many animal societies than small-scale human societies. Despotic human societies are organized to benefit a small group of elites at the expense of everyone else in the group. As a basic matter of trade-offs, what it takes to remain in power as a despot is different from what it takes to function well as a group. You can’t keep others under your thumb and then expect them to help you stay in power! Groups ruled by despots therefore tend to fare poorly in competition with more inclusive groups.

Between-group competition can take many forms, including but not restricted to direct warfare. Darwin stressed that nature is not always red in tooth and claw. A drought-resistant plant will outcompete a drought-susceptible plant in the desert, without the plants interacting with each other at all. The same goes for selection among human groups. A good example is the respect accorded to elders and deceased ancestors. Old people could easily be dominated by younger and stronger members of a group to the youngers’ relative advantage (within-group selection), but such groups would not benefit from the knowledge possessed by older people (between-group selection). The between-group advantage could take the form of remembering the location of water holes during a drought or recalling a winning strategy in direct between-group competition.

While direct conflict is not the only form that group selection takes, it is one of the major forms whenever there is something to fight over—which was increasingly the case with the advent of agriculture. Multilevel selection does not make everything nice. It is an inescapable fact that our admirable ability to cooperate within groups is due very largely to violent competition among groups. This is not something we want for the future, but it is a true statement about the past.

Following Peter, let’s drop in on two periods of human history, as revealed by written inscriptions on clay and stone tablets. The first is from Tiglath Pileser I, who ruled the Assyrian Empire from 1114 to 1076 BCE:

Then I went into the country of Comukha, which was disobedient and withheld the tribute and offerings due to Ashur my Lord: I conquered the whole country of Comukha. I plundered their movables, their wealth, and their valuables. Their cities I burnt with fire, I destroyed and ruined…Their fighting men, in the middle of the forests, like wild beasts, I smote. Their carcasses filled the Tigris, and the tops of the mountains…The heavy yoke of my empire I imposed on them.

And here is one from Ashoka the Great, who ruled the Mauryan Empire in the region of current-day India and Pakistan between 268 and 239 BCE:

Beloved-of-the-Gods speaks thus: This Dhamma edict was written twenty-six years after my coronation. My magistrates are working among the people, among many hundreds of thousands of people. The hearing of petitions and the administration of justice has been left to them so that they can do their duties confidently and fearlessly and so that they can work for the welfare, happiness and benefit of the people in the country. But they should remember what causes happiness and sorrow, and being themselves devoted to Dhamma, they should encourage the people in the country to do the same, that they may attain happiness in this world and the next.

Even adjusting for boastfulness in both emperors, what they chose to boast about speaks volumes about a brutal despotic culture on one hand and a more gentle inclusive culture on the other. What accounted for the flowering of social justice (relatively speaking), not just in the Mauryan Empire but throughout Eurasia during the same period? According to Peter, it was not the cessation of warfare but an increase in the scale of warfare.

The bullying tactics of despots who declare themselves to be gods don’t work above a certain scale. A relatively equitable society that holds even its kings accountable is required to achieve the next level of social organization; empires that span millions of square kilometers and include tens of millions of people. The religions, philosophies, and institutions that evolved during the so-called Axial Age (roughly the eighth to the third centuries BCE) provided the “social physiology” capable of holding such large societies together. This includes the spread of Buddhism in India, Taoism and Confucianism in China, and Christianity in the Roman Empire. They all emerged as different solutions to the problem of internal coordination required for successful between-group competition at a massive scale.

Between-group selection does not always prevail over within-group selection. A sufficiently fine-grained analysis of human history reveals both processes at work. Empires form in regions of chronic between-group warfare, which acts as a crucible for the cultural evolution of cooperative societies. Once one evolves that can coordinate action at a larger scale than its rivals, it expands to become an empire. Then cultural evolution takes place within the empire, favoring self-serving behaviors and factionalism in myriad forms. Eventually the empire collapses, like a cancer-ridden organism. According to Turchin, the centers of old empires become cultural wastelands for cooperation. New empires usually form at the edges of old empires, seldom at their centers. The increasing scale of society during the last ten thousand years has not been a smooth continuous curve. It has been a tug-of-war between levels of selection with a net gain for higher-level selection and many reversals along the way. The same tug-of-war operates in the present, with the evidence all around us once we know what to look for.

MULTILEVEL SELECTION AND CURRENT AFFAIRS

Ten thousand years of multilevel cultural evolution has led to the present moment, with roughly two hundred nations of various sizes, capable of regulating themselves for the common good to various degrees. Consider two small nations, Norway and Equatorial Guinea. Both are blessed with large oil reserves. Norway used its reserves to create the world’s largest pension fund for the benefit of its citizens (worth over a trillion dollars). Equatorial Guinea used its reserves to enrich the president, his family, and a small circle of elites. For the rest of the population, the life expectancy is fifty-one years, and 77 percent have an income of less than two U.S. dollars per day.

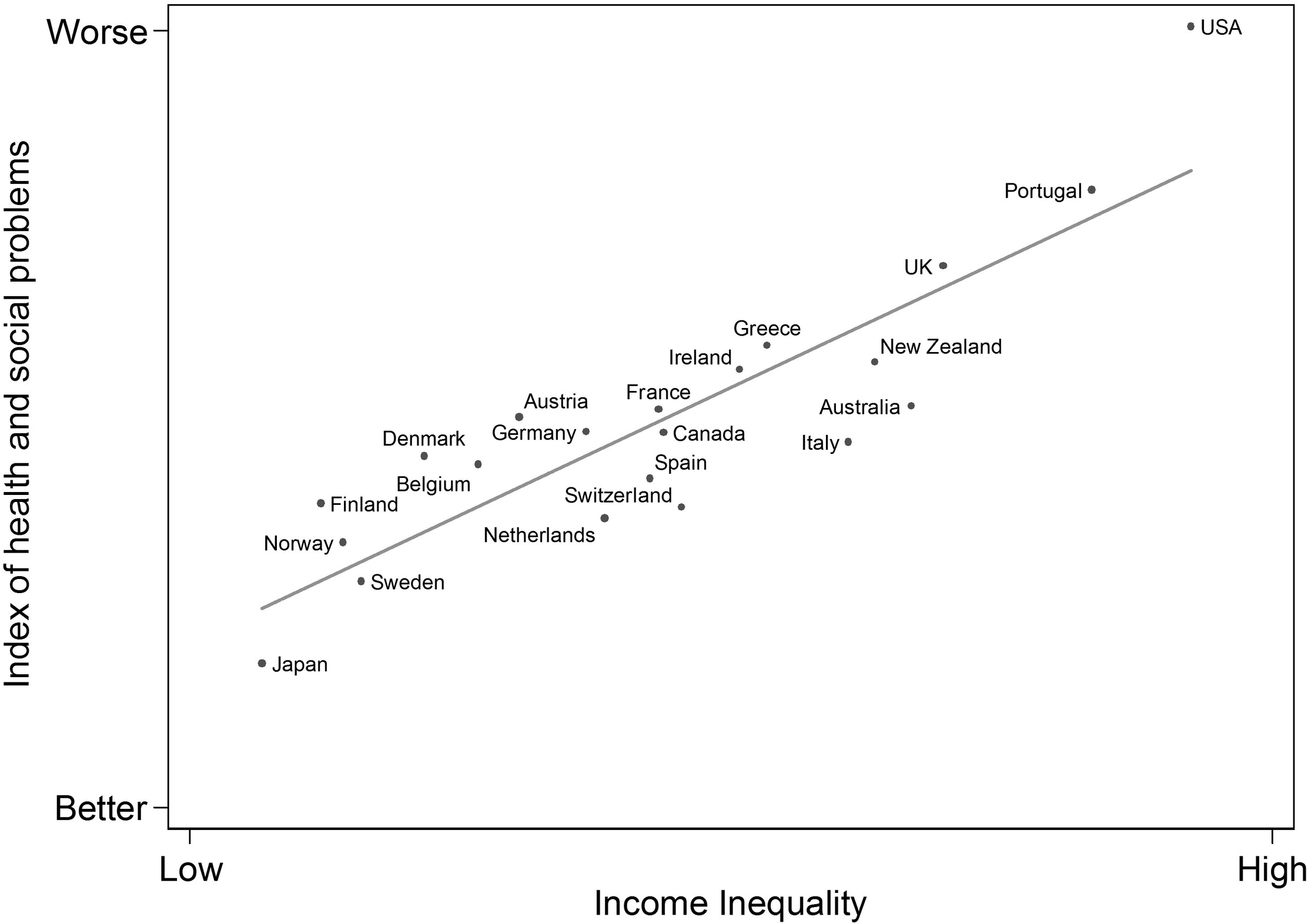

In this and many other ways, it is obvious that Norway qualifies as a corporate unit (a society that functions like an organism) much better than Equatorial Guinea.12 Books such as Why Nations Fail,13 by the political historians Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, and The Spirit Level,14 by the social scientists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, measure and diagnose variation among nations in their capacity to provide a high quality of life for their citizens. Here is one of many graphs from The Spirit Level, which relates an index of health and social problems to the degree of income inequality. The Nordic countries anchor the “better” end of the distribution, along with Japan, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. The U.K., Portugal, and the USA anchor the “worse” end of the distribution with the USA an outlier in both income inequality and health and social problems. According to the graph above and the more general diagnoses of these authors, the United States of America is doing a poor job regulating itself as a corporate unit.

Modern nations vary greatly in how well they function as corporate units.

These and related books have already been widely read and discussed in political and economic circles. The political economist Francis Fukuyama used the phrase “getting to Denmark” to pose the question of how any nation can work its way from the “worse” to the “better” end of graphs such as the one shown above.15 Defenders of American governance in its current form have a long list of reasons why America isn’t as badly off as the graph implies and why comparisons with the Nordic countries are inappropriate. They are so much smaller! They are more culturally homogeneous! Norway has oil (as if the USA doesn’t)!

An analysis based on Tinbergen’s four questions can add considerable value to these discussions, as all of the aforementioned authors are starting to appreciate. The history question acknowledges that cultural evolution, like all forms of evolution, can be highly path-dependent. Cultures don’t just change in any direction. Different histories mean that different mechanisms for regulating social processes are likely to have evolved (the mechanism question) and these mechanisms are likely to be transmitted across generations in different ways (the development question). If “nation building” is possible at all, it must be much more attentive to historical, mechanistic, and developmental questions than it has been in the past.

Despite formidable difficulties in “getting to Denmark,” Tinbergen’s function question provides a blueprint for all nations to follow. One way or another, all nations must be structured to suppress disruptive self-serving behaviors by individuals and subgroups. They also must be structured to coordinate the right behaviors in diverse contexts, even when cheating is not a problem. If a nation isn’t well regulated in the biological sense of the word, it will end up on the upper right side of graphs such as the one shown above.

Comparisons among nations are tricky because of their historical, mechanistic, and developmental differences. Perhaps the USA can never be like Norway or Denmark, but it doesn’t need to be. It merely needs to be like the USA at previous points in its own history.

AGES OF UNITY AND DISCORD IN AMERICA

The analysis of variation within a given nation at different points of its history circumvents many of the problems associated with comparisons among nations. America wasn’t always the land of inequality. It used to anchor the other end of the distribution, not once but twice during its 250-year history. In fact, the European colonization of the Americas provides a remarkable lesson in cultural multilevel selection, once we know what to look for.

As chronicled by Acemoglu and Robinson in Why Nations Fail, when the Spanish and Portuguese colonized Central and South America, they encountered societies that were already hierarchical and were able to become the new elite ruling class, governing for the benefit of themselves and not the population as a whole. This “extractive” social organization has continued to this day, illustrating just how entrenched extractive forms of governance can be. Most Central and South American nations function poorly as corporate units and always have. It is part of their cultural DNA.

The first British colonies in America, such as the Jamestown colony founded by the Virginia Company in 1607, also intended to rule over the Native Americans. When that didn’t work, they tried to re-create a European feudal society by importing British laborers, who were made to live in barracks and work for rations; they were executed if they attempted to escape, much like slaves. But the British laborers had other options in America. Despite threat of death, they could and frequently did leave to become frontiersmen. By 1618, the colony was forced to adopt a more equitable social organization in order to survive. Each male settler was granted his own plot of land and all adult men had a say in the laws and institutions governing the colony. A very intense period of cultural evolution at the scale of small groups transformed an extractive social organization into an inclusive social organization, at least for adult white landowners. This experience was repeated in each of the thirteen colonies that coalesced to become the United States of America. That’s why America grew to become a vibrant democracy (at least for white males), in contrast to the Central and South American nations.

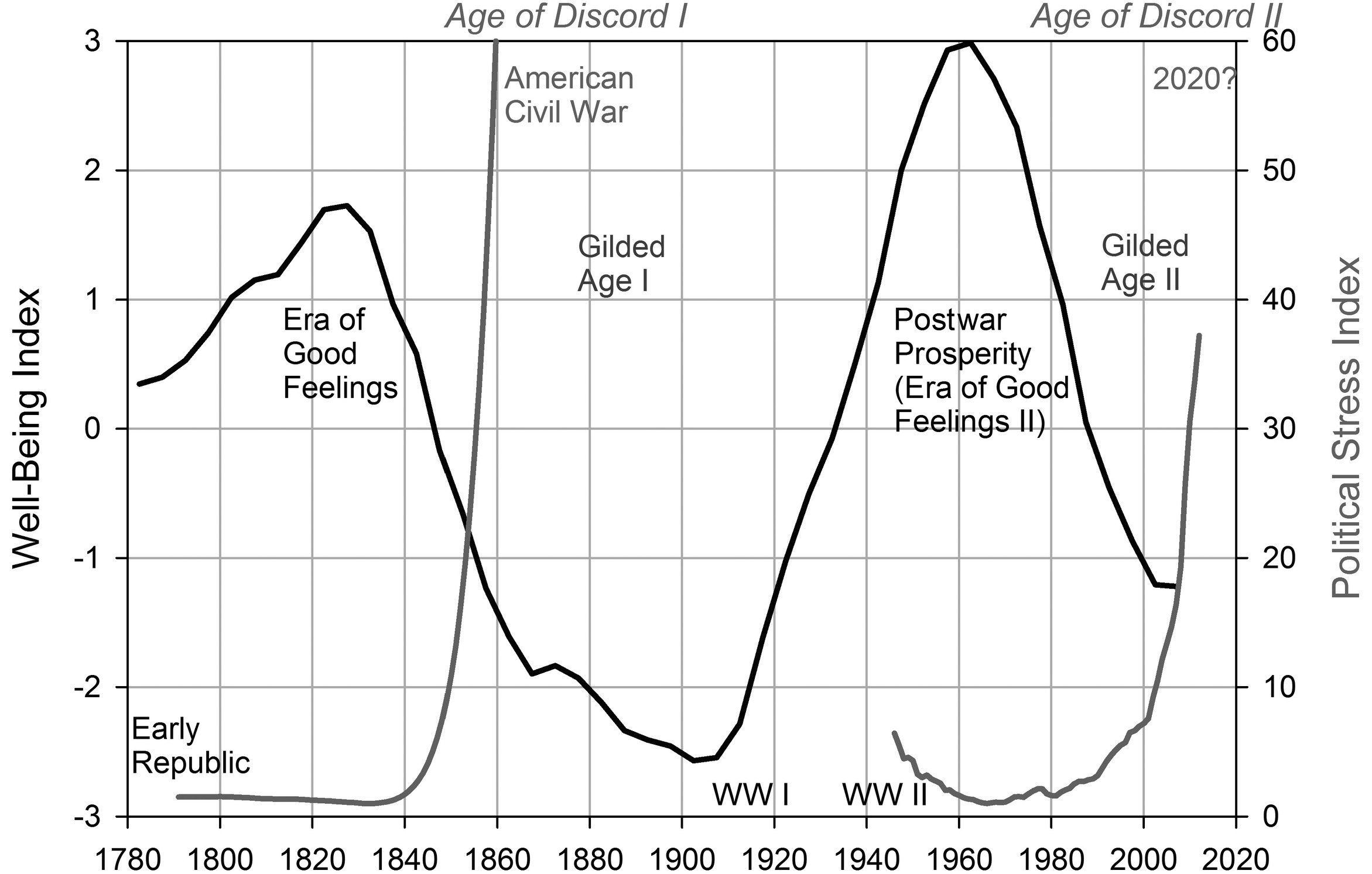

Unfortunately, the checks and balances of the American Constitution did not entirely protect the fledgling nation from social processes that benefitted some people at the expense of others and the nation as a whole. To get the clearest view of America’s swing toward inequality, it is best to turn from narrative historical accounts, such as the one offered by Acemoglu and Robinson in Why Nations Fail, to Peter Turchin’s cliodynamic approach. The graph on page 189 is from Peter’s newest book, Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History. The solid line is an index of well-being, similar to the y-axis of the graph from The Spirit Level shown on page 186 (but with the poles reversed). It starts out high and rises to a peak in the 1830s. This is described as “the Era of Good Feelings” by historians and was immortalized by the French diplomat and social theorist Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, which he wrote based on his travels during 1831.

History as science. Well-being in America has swung like a pendulum during its history and is currently at a low point.

Then the index of well-being starts to decline. The America of 1900, dubbed “the Gilded Age” by historians, was no longer the America of the 1830s described by de Tocqueville. Notice that the Civil War took place at the halfway point of the decline. Oddly, this cataclysmic event in American history neither caused the decline nor seemed to have had much of an effect on the index of well-being.

Like a pendulum moved by hidden forces, the index of well-being begins to rise again, reaching a peak during the 1960s. The Great Depression, another convulsive event in American history, occurs partway up this slope. Like the Civil War, it seems neither to have caused nor to have had much of an effect on the pendulum swing. The next decline begins in the 1970s. The election of Ronald Reagan, which is regarded as a watershed in American political history, occurs partway down this slope, more like a symptom than a cause.

Graphs such as the two that I have presented are so common that we tend to either accept or reject them on faith, trusting or distrusting the experts who made them, without making our own examination. It is therefore worth spending a bit more time describing Peter’s methods as a master evolutionary scientist at work. The kind of census data that Wilkinson and Pickett use in The Spirit Level doesn’t extend very far back in time. To create a well-being curve for the entire span of American history, Peter used four proxies that could be assembled from historical records. The first is an index of relative wages, or income inequality. The second is physical stature (height at adulthood). The third is average age of marriage. The fourth is average life expectancy. Three of the four proxies are hard biological measures of well-being. If you didn’t have enough food to grow as tall as you might have, if you had to wait longer to get married than you might have, and if you flat-out died sooner than you might have, then your well-being was comparatively low.

Each proxy for well-being is based on historical information of variable quality. Even though the data is noisy, when you chart the four proxies separately on a graph, they line up fairly well with each other. When you estimate something in four different ways using different sources of information and they all line up, something is going on that isn’t likely to be attributed to measurement error. The more you examine Peter’s methods of gathering historical time series data, the more you trust that the pendulum swings shown in the figure are real.

That’s only half of what Peter accomplishes in Ages of Discord. The other half is a model of the social forces that cause the pendulum of well-being to swing. The model includes four major compartments and their interrelations: (1) The State (Size, Revenues, Expenditures, Debt Legitimacy); (2) The Population (Numbers, Age Structure, Urbanization, Incomes, Social Optimism); (3) The Elites (Numbers, Composition, Incomes and Wealth, Conspicuous Consumption, Social Cooperation Norms, Intra-elite Competition/Conflict); and (4) Forces of Instability (Radical Ideologies, Terrorism and Riots, Revolution and Civil War). In addition to his index of well-being, Peter has estimated all of these other variables with historical data, which he uses to build computer simulations—virtual Americas to compare with the real America.

If all of this sounds dauntingly complex, it is no more so than modeling the pendulum swings of bark beetle populations, forest fires, and epidemics, which was Peter’s previous line of work. In other words, the complexity does not prevent us from making solid scientific progress. For example, models of disease transmission often divide the host population into three compartments: susceptible individuals, infected individuals, and individuals that have recovered and become immune. Peter uses the same models, virtually unchanged, to examine the cultural transmission of radical political ideologies.

The gray lines in Peter’s graph are a political stress index, which is based on the voting records of the two major political parties in the United States Congress (currently the Democratic and Republican parties). The ideological differences between the two parties were minor up to the 1840s and then spiked upward just prior to the Civil War. Alarmingly, the same trend is occurring today. We seem to be on the brink of a new Age of Discord. It probably won’t take the form of a civil war, but it might take the form of riots, terrorist acts, and social chaos. Worse, other nations seem to be on the brink of their own Ages of Discord. In the tug-of-war between levels of selection, disruptive within-group competition appears to be winning.

Thankfully, the situation is not hopeless. Human history is not like a mechanical pendulum. It responds to human agency. By taking the right kind of collective action, we can pull back from the brink. This is not just a conjecture about the future; it is a statement that we can make about our own past.

Let’s return to the last nadir of well-being in American history, the early 1900s. Income inequality was at an all-time high. The rich were never richer and the poor were working for starvation wages. The economy was collapsing. Riots and terrorist events were on the rise and communism was threatening to upset the entire world order. The situation was so dire that some of the elites of America began to formulate policy with the welfare of the whole nation in mind, even at their own relative expense. Put another way, they realized that if they didn’t subordinate their own well-being to the well-being of the nation, they might well go down with the ship. Their decision was like the decision of the Virginia Company that its tiny colony on the banks of the James River must become more inclusive to survive.

Thanks to this collective decision, America pulled back from the brink and the well-being of the average American started to rise. They didn’t just bring home a larger paycheck—they grew taller, married earlier, and lived longer. What could have become the Era of Total Collapse turned into the New Deal, which Peter has dubbed the Second Era of Good Feelings, to stress its similarity to the previous one.

John D. Rockefeller is one of the corporate giants who had a change of heart. Previously a believer that his money was a sign from God and that industrial paternalism (power concentrated in the hands of people like himself) was best for the nation, he made this statement in 1919: “Representation is a principle which is fundamentally just and vital to the successful conduct of industry…Surely it is not consistent for us as Americans to demand democracy in government and practice autocracy in industry…With the developments of industry what they are today there is sure to come a progressive evolution from autocratic single control, whether by capital, labor, or the state, to democratic cooperative control by all three.”

And so there was. Labor unions became strong, the state played an active role in social welfare and industrial development, and the tax rate on the top income bracket rose to a level comparable to that in the Nordic countries today. These changes were not forced upon the elites—they were accomplished by the elites based on a political philosophy that stressed the welfare of the whole nation, or the whole organism, as necessary for their own long-term welfare. But alas, people have a way of forgetting the lessons of history, especially when they can profit by their forgetfulness over the short term. Selfish interests and ideologies that justified individual and corporate greed as good for the whole group began to spread, leading to our decline in well-being and increase in political discord to the present moment, as Peter’s graph shows.

THE FINAL RUNG

If ever there was a case of a wrong theory blinding us to reality, it is the current “greed is good” ethos of orthodox economic theory. However, you can’t discard an old theory without adopting a new one. An evolutionary worldview provides a robust alternative that is remarkably simple to envision. We merely need to replace the pre-Darwinian concept of a natural order with the Darwinian concept of a unit of selection. Multilevel selection theory provides a framework for understanding the design of small groups, the increase in the scale of society over the last ten thousand years, and the current frontiers of human social organization, which can either advance to achieve a global scale or disintegrate into smaller corporate units that make life miserable for each other.

One conclusion is that for any group to function as a corporate unit, the potential for disruptive self-serving behaviors within the group must be suppressed. This conclusion is so basic that it applies to nonhuman species in addition to human groups of any size. It is remarkable that the core problem confronting America in the early twentieth century and today is the same problem that confronted the tiny Jamestown colony in the early 1600s: an extractive social organization that allows some to gain at the expense of others and the group as a whole. This is the human societal equivalent of cancer.

It is important to stress that disruptive self-serving behaviors need to be judged by actions, not intentions. Consider Alan Greenspan, the economist who served as the U.S. Federal Reserve Board chairman from 1987 to 2006. By all accounts he was a well-intentioned man who thought he was improving the welfare of the nation and the world, but he was a major player in the decisions that led to the decline of well-being in America during this period. A well-intentioned person blinded by the wrong theory is little better than a person driven by selfish impulses. As the novelist and existential philosopher Albert Camus wrote: “The evil of the world comes almost always from ignorance, and goodwill can cause as much damage as ill-will if it is not enlightened…There is no true goodness or fine love without the greatest possible degree of clear-sightedness.”

Another conclusion is that for any group to function as a corporate unit, it must be well regulated in the biological sense of the word. Countless processes must be kept within bounds to meet the challenges of survival and reproduction. What is true for a multicellular organism or a social insect colony is also true for a human society. Whenever I hear talk of regulations as categorically bad, I feel like shouting “An unregulated organism is a dead organism!”

Yet it is also absurd to think that all regulations are good. Regulations are like mutations—for every one that works well for a group, there are many that work poorly. Also, it is a mistake to associate regulation exclusively with government controls and centralized planning. Most regulatory systems in the biological world are decentralized and self-organizing. Much of the regulation in small-scale human groups takes place spontaneously and beneath conscious awareness, thanks to our genetically evolved psychological mechanisms. The biological concept of regulation does not map onto any current political ideology. That’s why an evolutionary worldview is in a position to provide new solutions that can appeal across the political spectrum.

A third conclusion follows directly from multilevel selection theory. Adaptation at any level of a multi-tier hierarchy requires a process of selection at that level. The whole cannot be optimized by separately optimizing the parts. That’s why the concept of the invisible hand in orthodox economic theory, which pretends that the pursuit of lower-level self-interest robustly benefits the common good, is so deeply flawed.

As an example, consider so-called “smart city” movements that are taking place around the world. To say that a city can be smart is to say that it can have something analogous to a nervous system and brain, which receives and processes information in a way that leads to effective action. This can include a technological component, such as electronic sensors that monitor traffic flow, but it also can include a human component, such as 311, a three-digit number that residents of a city can call to communicate a problem such as a pothole, a fallen tree, or a failure to pick up garbage.16 The use of the number originated as a “cultural mutation” in Baltimore, Maryland, in the 1990s to process calls that were being inappropriately made to 911, which is designed to handle urgent matters. Soon the potential of 311 to turn residents into the “eyes and ears” of a city began to become apparent, with cities such as Boston taking the lead. When Hurricane Irene struck the East Coast of the United States in 2011, the city of Boston received 1,045 reports of “tree emergencies” during a forty-eight-hour period through its 311 system, enabling it to decide how to deploy its maintenance crews without needing to gather the information in other ways. Currently the city receives about 175,000 calls to 311 annually, and similar systems have been implemented in over four hundred American cities.

The metaphorical description of 311 as the “eyes and ears of the city,” along with catchphrases such as “the pulse of the city,” indicates the intuitive appeal of thinking of a city as a single organism with a “social physiology” that receives and processes information in a way that leads to effective action. These processes seem “automatic,” “effortless,” and “self-organizing” in single organisms. We see and hear without needing to think about it—but only thanks to enormously complex mechanisms that evolved by natural selection at the level of single organisms. If something similar is going to evolve at the scale of a city, it will need to be selected as a whole system. Systems engineers have known this for a long time, but only recently have they started thinking of what they do as a highly managed form of cultural group selection.17

It is useful to make a distinction between “natural” and “artificial” cultural group selection, similar to the distinction between natural and artificial selection in the biological sciences. The shape and coloration of a moth that exactly resembles a leaf is a product of natural selection, based on the removal of more conspicuous moths by predators. The shape and coloration of the flowers in your garden are a product of artificial selection, based on the removal of plants with less showy flowers by humans. The same basic principles of evolution are at play in both cases. Also, the distinction between natural and artificial selection is not always clear-cut. In many species of animals, members of one sex (usually but not always the males) are highly ornamented because they were selected as mates by members of the opposite sex, much like human gardeners selecting showy flowers. The domestication of dogs probably began with the natural selection of wolves that began to hang around human habitations, not the deliberate selection of these wolves by people.

In human cultural evolution, the line between artificial and natural selection is even more blurred. Human cultural change is intentionally guided to some extent but it is also a product of many inadvertent social experiments, some that hang together and others that fall apart. The Protestant Reformation provides an excellent example. Reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin were very deliberative in the construction of their theologies and social ordinances, but the consequences of their intentional efforts were highly variable, based on unforeseen consequences. Calvinism in Geneva was not the sole product of Calvin but a complex interaction between Calvin’s efforts and many other people and events. The fact that this complex interaction resulted in a city that functioned well, compared to the efforts of other reformers such as Huldrych Zwingli in the city of Zurich, would have been impossible to predict beforehand. Intentional actions are often converted into chance actions when they collide with each other!

The most important conclusion for our purposes is that cultural group selection must become more intentional and deliberative than ever before. We can’t wait decades and centuries for our inadvertently successful social experiments to spread. We must learn to function in two capacities: as designers of social systems and as participants in the social systems that we design. As designers, we must have the welfare of the whole system in mind, such as the welfare of a city in the construction of a 311 telephone system. The invisible hand concept does not apply. As participants, we can only have our own local concerns in mind, such as punching three digits into our smartphones when there is a problem in our neighborhood. The invisible hand concept does apply. In short, system-level selection is the invisible hand that causes local actions to benefit the common good. The invisible hand must be constructed, which is a contradiction of terms according to the concept of laissez-faire.

Finally, even if we succeeded at creating smart cities or smart nations, that would not solve the problems of coordination at larger scales. The conclusion is inescapable: To solve problems at the planetary scale, we must formulate policies with the welfare of the whole planet in mind. “Me first,” “Our corporation first,” and “Our nation first” are not good enough. It must be “Our world first.” The lower-level units don’t disappear. On the contrary, their welfare is paramount, but in the process of thriving they must contribute to rather than undermine the higher-level common good. A multicellular organism can’t be healthy without its cells and organ systems being healthy—but there is still a difference between a healthy normal cell and a healthy cancer cell. Even a nation such as Norway, which works so well at the national scale, must regulate its behavior (such as the global investment strategy of its pension fund) to avoid becoming part of the problem at the planetary scale.18

The challenges of getting all nations to function as well as Norway (or Denmark) are daunting, not to speak of ascending the final rung to become a worldwide corporate unit, but at least we have the right theory to guide us.