Prologue

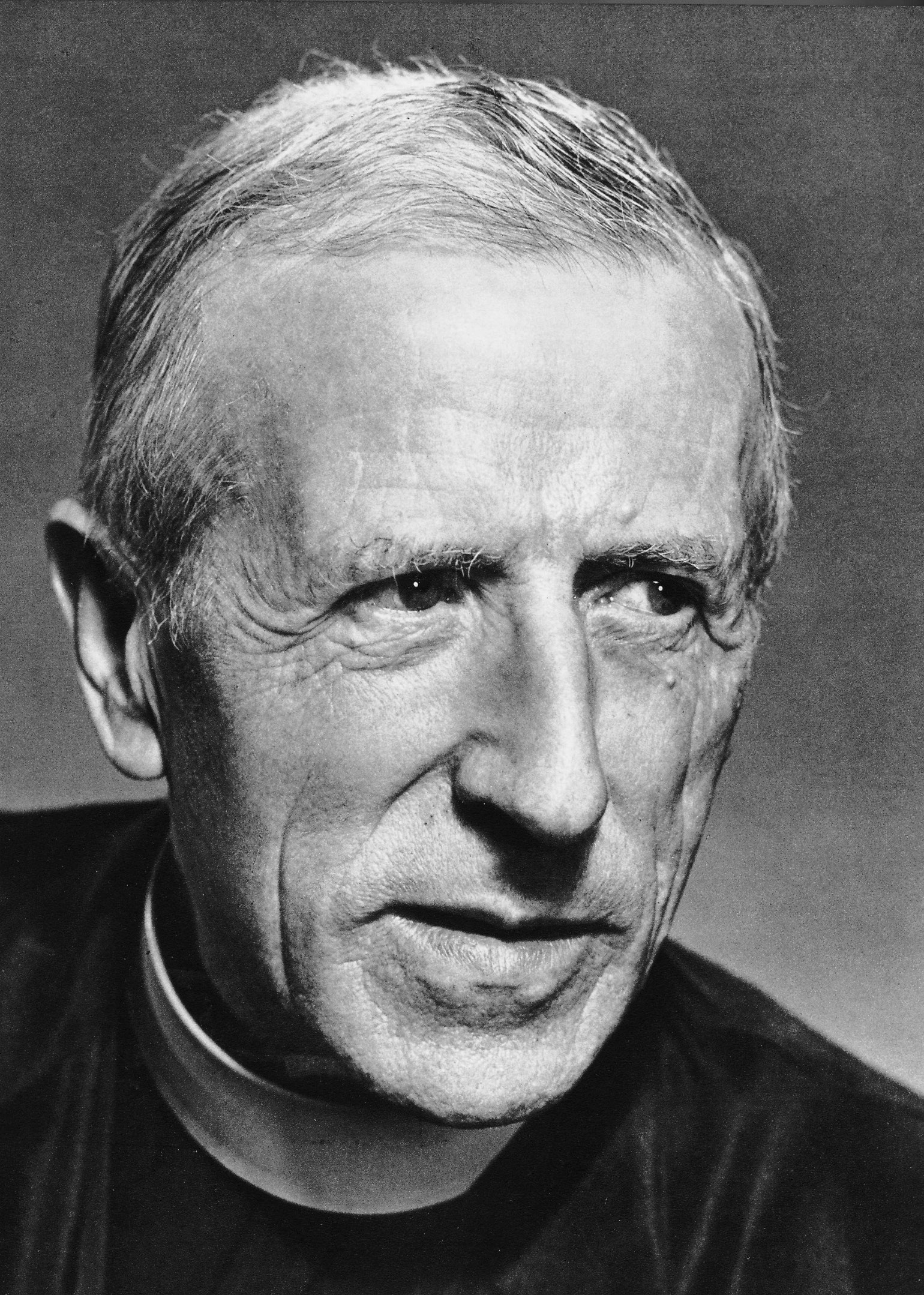

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), a scientist and Jesuit priest, made an observation about humankind that departed from both Christian doctrine and the scientific wisdom of his day: In some respects we are just another species, a member of the Great Ape family, but in other respects we are a new evolutionary process. That makes the origin of our species as significant, in its own way, as the origin of life.

Teilhard lived at a time when the Catholic Church still regarded science as a legitimate path to God. Like his predecessor, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), he was both authorized to study the natural world and restricted when his inquiry began to threaten religious dogma. Whereas Galileo gazed at the heavens, Teilhard dug in the earth for fossils. He was a paleontologist and part of the team that discovered Peking Man (now classified as Homo erectus), one of the first fossil skulls that provided a “missing link” between us and our more apelike ancestors. Whereas Galileo was threatened with torture, Teilhard was blocked from accepting prestigious academic positions and forbidden to publish his work. His best-known book, The Phenomenon of Man, was written in the 1930s and Teilhard waited patiently until the end of his life before privately arranging for it to be published posthumously.1

In this panoramic work, he describes earth before the origin of life as just another barren planet shaped by physical processes. Then, living organisms began to spread over its surface like a kind of skin. They too were “just” a physical process. Teilhard resisted the temptation to invoke a divine spark to explain the origin of life. But living organisms differ from non-living physical processes in their capacity to replicate and diversify into “endless forms most beautiful,” as Darwin wrote in the final passage of On the Origin of Species. Over immense periods of time, living processes began to rival non-living physical processes in shaping the planet and atmosphere, giving earth the unique appearance of a multicolored jewel when viewed from space. Using a word coined by the geologist Eduard Suess in 1875, Teilhard called the influence of life on the planet earth the biosphere.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: Scientist and Priest

Next, Teilhard asks us to imagine one species, located on one twig of the tree of life, that begins to proliferate and diversify much more rapidly than the other twigs. In an astonishingly short period of time, a new skin spreads over the earth, rivaling other living processes and non-living physical processes in shaping the planet and atmosphere. That species was Homo sapiens, and Teilhard coined a new word, the noosphere, to describe the second skin.

This word is derived from the Greek word for “mind” (nous), signifying that the new skin has a mental dimension in addition to a physical dimension. Teilhard described consciousness as a process of evolution reflecting upon itself. He portrayed the human colonization of the planet as starting with “tiny grains of thought” that would eventually merge with each other to form a global consciousness and self-regulating superorganism called the Omega Point.

The idea that we are part of something larger than ourselves, which could be considered an organism in its own right, has been expressed a thousand different ways in cultures around the world. So too has the idea that the “something” is expanding—or at least needs to—ultimately embracing all of humankind and the planet earth. Sometimes these ideas are given a religious and spiritual formulation, but they also lie behind practical efforts to create good governments and economies and to expand their scales. From a purely secular perspective, Teilhard’s Omega Point corresponds to the vision of a world where governments work together for the good of their citizens and live in balance with the rest of life on earth. We seldom associate politics and economics with religion and spirituality, and in many ways we feel the need to keep them apart, as with the separation of church and state. Nevertheless, words such as “corporation” (derived from the Latin for “body”) and phrases such as “body politic” signify that whatever we mean by the word “organism” can be applied to entities that are larger than organisms, such as a human society or a biological ecosystem.

Teilhard’s cosmology was new, compared to his Christian faith and all other previous cosmologies, because it was based on Darwin’s theory of evolution. As a scientist, he could claim the authority of the best factual knowledge of his day. As a priest, his writing had an inspirational quality that went beyond a purely scientific treatise. Alone, science only tells us what is and not what ought to be. To get from “is” to “ought,” we must combine facts with values. It is a fact that torture causes pain, but we need the value that causing pain is wrong before we can conclude that we ought not to torture. Teilhard described the Omega Point as not just a theoretical possibility but a sort of heaven on earth worth pursuing with one’s heart and soul.

Today, over half a century after his death, Teilhard remains widely read for his spiritual quality but has been largely forgotten by scientists. That’s a pity, because The Phenomenon of Man was scientifically prophetic in many ways. Living processes indeed rival non-living physical processes in shaping the planet earth and its atmosphere. As we are increasingly coming to realize, our species does represent a new evolutionary process—cultural evolution—that far surpasses cultural traditions in other species. This capacity for cultural evolution enabled our ancestors to spread over the globe, inhabiting all climatic zones and dozens of ecological niches. Then small-scale societies—“tiny grains of thought”—coalesced into larger and larger societies over the past ten thousand years. Human activities now rival other living processes and non-living physical processes in shaping the earth and atmosphere, exactly as Teilhard said. It’s even true that the Internet and other technological marvels are capable of furnishing the earth with a planetary brain.

This book can be seen as an updated version of The Phenomenon of Man. It is fully scientific, based on the best of our current knowledge about evolution, which has grown vastly more sophisticated since Teilhard’s day. It also unabashedly goes beyond what is to provide a blueprint for what ought to become. Modern evolutionary theory shows that what Teilhard meant by the Omega Point is achievable in the foreseeable future. However, the same theory shows that its achievement is by no means certain. The reason is that evolution is both the solution and the problem. The harmony and order that we associate with the word “organism” indeed has a movable boundary that can be expanded to include biological ecosystems, human societies, and conceivably the entire earth. Special conditions are required, however, and when these conditions are not met, evolution takes us where we don’t want to go. There is no master navigator for our journey. We must be the navigators, consciously evolving our collective future, and without the compass provided by evolutionary theory, we will surely be lost.