TRADITIONS OF BELTAINE

Countries the world over celebrate the first of May with joyful festivals designed to drive away the chill winds of winter and welcome in the warm breath of spring. While the celebrations may be called by different names, they are all held in a similar fashion. Celebrants dance and sing around Maypoles or May bushes, leave offerings to Fairies and Gods in return for protection and prosperity, burn ritual fires in their homes and on hilltops, and enjoy great feasts of food and libation. But there are also many creative variations on how each country honors the season of fertility and new beginnings, and these are described below.

Traditional Beltaine Customs in Britain

I have heard it credibly reported by men of great gravity, credit and reputation; that of forty, threescore or a hundred maids going to the woods overnight, there have scarcely the third part of them returned home again undefiled.

PHILIP STUBBES, PURITAN WRITER

In England it was once the custom for the young men and females of the village to spend May Eve together in the woods. Later they would come home bearing blooming branches, especially of Hawthorn. Babies born of this event were called Jackson (son of Jack in the Green), Hodson (son of Hod, a woodland Spirit) or Robin (after Robin Goodfellow or Robin Hood, both aspects of the Green Man, a potent male Spirit of the vegetation).1

In Celtic Britain it was believed that on May Eve Witches and Fairies would transform into hares and travel the countryside to steal milk and the health of the herds. It was said that the only way to stop a Witch in hare’s form was to shoot her with a silver bullet.

As we know Witches are healers and midwives, which is why they may have been associated with hares, many parts of which were used for medicine: the gall for eye issues, the blood for skin conditions, and so on. According to the Welsh physicians of Myddfai the brains of a hare mixed with powdered Rosemary flowers and roasted was a sovereign remedy for vertigo and migraine.2

Witches wanting to do mischief on May Eve might hide secret objects under a cow’s tail or steal your cheese-making and churning implements, so the household butter and cheese had to be made before dawn to divert the Fairies’ attention and dairying equipment had to be well hidden on May Eve.3

Morris dancing and mummer’s plays are still performed on Beltaine today. Characters such as the hobby horse, a Green Man, a jester, a Betty (a man dressed as a woman), and a chimney sweep are featured. A ritual battle between the Oak King (summer) and Holly King (winter) is staged where the Oak King always triumphs. The May Queen, a veiled symbol of the Goddess, presides over the battle.

The Maypole is a well-known British tradition associated with May Day. The pole is a phallic symbol that fits snuggly inside a hole in the earth. Puritan writer, Philip Stubbes describes it as follows:

They have twenty or forty yoke of oxen, every ox having a sweet nosegay of flowers tied on the tip of his horns, and these oxen draw home this Maypole (this stinking idol rather) which is covered all over with flowers and greens, bound roundabout with ribbons from top to bottom, and sometimes painted with variable colors, with two or three hundred men and women and children following it with great devotion. And this being reared up with handkerchiefs and flags streaming on the top, they strew flowers on the ground, bind green boughs about it, and set up summer halls, bowers and arbors, hard by it. And then fall they to banquet and feast, to leap and dance about it as the Heathen people did at the dedication of their idols, whereof this is a perfect pattern, or rather the thing itself.4

Traditional Beltaine Customs in Ireland

While the English danced around their Maypoles, the Irish decorated a May Bush with yellow flowers such as Marsh Marigold, Buttercups, and Primroses along with yellow ribbons and egg shells dyed yellow to honor the sun.

The May Bush was often a Hawthorn, a Rowan, or a Sycamore. There were household bushes and public bushes, and these could be stationary or carried around the village. Towns competed to see which one produced the most beautiful tree and would even resort to stealing each other’s creations. After it was danced around the May Bush was left up for a month, then burned in a bonfire. The honoring of the bush was connected to the ancient Fairy faith and a way of bringing the blessings of the tree Spirits into the community.

Ferns and yellow flowers such as Furze were placed on doorsteps and windowsills to honor the sun and enchant the Fairies. The idea was that the Fairies would be so entranced by the Fern and Furze’s smell that they would ignore the inside of the house. Yellow flowers were also used to decorate wells as a form of protection from mischievous Spirits.

Gifts of food or milk were left on a doorstep or under a Fairy tree. Cattle were taken to Fairy forts and a small amount of blood was drawn and then poured on to the earth as an offering to protect the herd.

Other activities at Beltaine included paying and renewing rents, paying tithes, and going to regional fairs to look for employment. It was also a time to ritually protect boundaries by burying offerings at borders to ensure that ill-intentioned Witches and evil Spirits would not harm the farm. To ensure that the health and fertility of their land, farmers processed around the boundaries carrying grain seeds, farm tools, well water, and Vervain or Rowan, stopping in the north, east, south, and west of their properties to say a prayer and make an offering.5

Beltaine marked the portal between winter and summer, a liminal time of chaos and change when Spirits were about and human mischief was always possible. As Lora O’Brien describes in her article “Irish Pagan Magic—Piseoga”:

May Day morning, the turning of the year at Bealtaine from winter into summer, and so a time for changes. A malevolent person could go out on this particular morning and mix rotten produce into your farm—to try and turn your luck. This could be rotten meat in the haystacks, or rotten eggs in through the soil . . . either way the imagery is clear, and unless the foulness was found your luck would turn. Of course, the sensible farmer would have already taken precautions against this type of shenanigans and deployed one of the many available counter charms to turn aside ill intent in plenty of time for the big day.6

Milk was also thought to be strangely affected on Beltaine. In his book Superstitions of the Irish Country People, Padraic O’Farrell states:

The giving away of milk, always suspect, had further implications upon May Day for whoever got milk of a cow first on that day received the profit from that cow for the remainder of the year. . . . This belief was so strong that a court of law is said to have ruled in favor of a man who struck down an intruder in his byre on May Day, believing him to be after his milk A dying woman was refused milk on May Eve on one recorded occasion.7

Traditional Beltaine Customs in Scotland

In early May in Scotland the bothies—rough shelters built in the hills to accommodate the women and children who followed the cows—were repaired and then the whole community followed the herd to pastures in the hillsides, known as shielings. In general the men returned to the farms to tend the crops or set out to sea for the fishing while the rest of the clan stayed to tend the cows.

These activities were not necessarily done on May 1, however. The weather had to be warm enough on the mountainsides for the cows, the new calves, and the families who would tend them. One way to determine if the elements were favorable was to observe the blooming of the Hawthorn tree, as it only blooms when the danger of frost is over. This meant that the shieling season could start as early as March or as late as June. The blooming of the Hawthorn also signaled that the soil was warm enough for planting.

The procession to the summer grazing began at dawn when everyone gathered their belongings and flocks and began the trek. The sheep went first, then the cattle, then the goats and horses. Songs of protection were sung over the herds as a type of incantation. Following is an excerpt from a song called “An Saodachadh (The Driving)” from Alexander Carmichael’s nineteenth-century Carmina Gadelica.

The protection of Odhran the dun be yours,

The protection of Brigit the Nurse be yours,

The protection of Mary the Virgin be yours,

In marshes and in rocky ground,

In marshes and in rocky ground.

The keeping of Ciaran the swart be yours,

The keeping of Brianan the yellow be yours,

The keeping of Diarmaid the brown be yours,

A-sauntering the meadows,

A-sauntering the meadows.

The safeguard of Fionn mac Cumhall be yours,

The safeguard of Cormac the shapely be yours,

The safeguard of Conn and Cumhall be yours

From wolf and from bird-flock

From wolf and bird-flock . . .8

Another example is the following excerpt from a traditional Scottish Beltaine blessing also taken from Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica.

Bless, O Threefold true and bountiful,

Myself, my spouse, and my children,

My tender children and their beloved mother at their head.

On the fragrant plain, on the gay mountain sheiling,

On the fragrant plain, on the gay mountain sheiling.

Everything within my dwelling or in my possession,

All kine and crops, all flocks and corn,

From Hallow Eve to Beltane Eve,

With goodly progress and gentle blessing,

From sea to sea, and every river mouth,

From wave to wave, and base of waterfall . . .9

Other ritual activities included the offering of a caudle to the Land Spirits and the breaking of a large bannock into pieces, which were distributed to each family member, who then threw it over their shoulder as an offering for protection of the farm, as Thomas Pennant describes in A Tour in Scotland, and Voyage to the Hebrides 1772.

On the first of May, the herdsmen of every village hold their Bel-tein, a rural sacrifice. They cut a square trench on the ground, leaving the turf in the middle; on that they make a fire of wood, on which they dress a large caudle*104 of eggs, butter, oatmeal and milk; and bring, besides the ingredients of the caudle, plenty of beer and whisky, for each of the company must contribute something. The rites begin with spilling some of the caudle on the ground, by way of libation: on that everyone takes a cake of oatmeal, upon which are raised nine square knobs, each are dedicated to some particular being, the supposed preserver of their flocks and herds or to some particular animal, the real destroyer of them: each then turns his face to the fire, breaks off a knob, and flinging it over his shoulders says ‘This I give to thee, preserve thou my horses; this to thee, preserve thou my sheep’; and so on. After that, they use the same ceremony to the noxious animals: ‘This I give to thee, O Fox! Spare thou my lambs; this to thee, O hooded Crow! this, O Eagle!’ When the ceremony is over, they dine on the caudle.10

Fire figured prominently in many of the Beltaine rituals. One example was the saining (ritual purification) of the herds by smoke.

The shepherds purified their flocks with the smoke of sulphur, juniper, boxwood, rosemary &c. They then made a large fire round which they danced, and offered to the goddess milk, cheese, eggs, &c. holding their faces towards the east and uttering ejaculations peculiar to the occasion.11

In another such ritual a fire was carefully constructed over which a younger member of the community would leap; the height of their jump would determine the height of the coming grain crop. Lots were cast to see who would jump. To do this, a bannock was broken into pieces and one piece was charred black. All the pieces were put into a hat, and whoever drew the charred section was required to jump the flames.

Also during Beltaine, household fires were relit from the communal fire, and all debts and rents had to be paid before the new home fire was kindled. Once the new fire was in the hearth a ritual feast was prepared that featured a male lamb, bannocks, a caudle, and a special May Day cheese made with ewe’s milk that was cured for 12 months and had to be eaten by sundown on May Day to keep ill-intentioned Fairies at bay for a full year.

Plate 49. Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia)

Plate 50. Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis)

Plate 51. Rue (Ruta graveolens)

Plate 52. Sage (Salvia spp.)

Plate 53. Saint John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Plate 54. Strawberry (Fragaria spp.)

Plate 54. Strawberry (Fragaria spp.)

Plate 56. Sweet Woodruff (Galium odoratum)

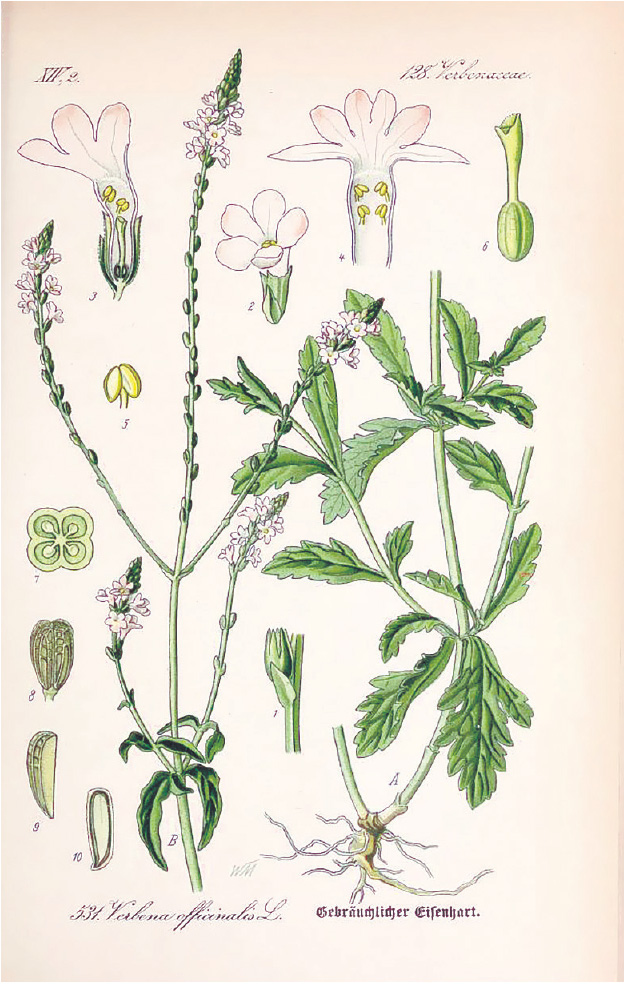

Plate 57. Vervain (Verbena officinalis)

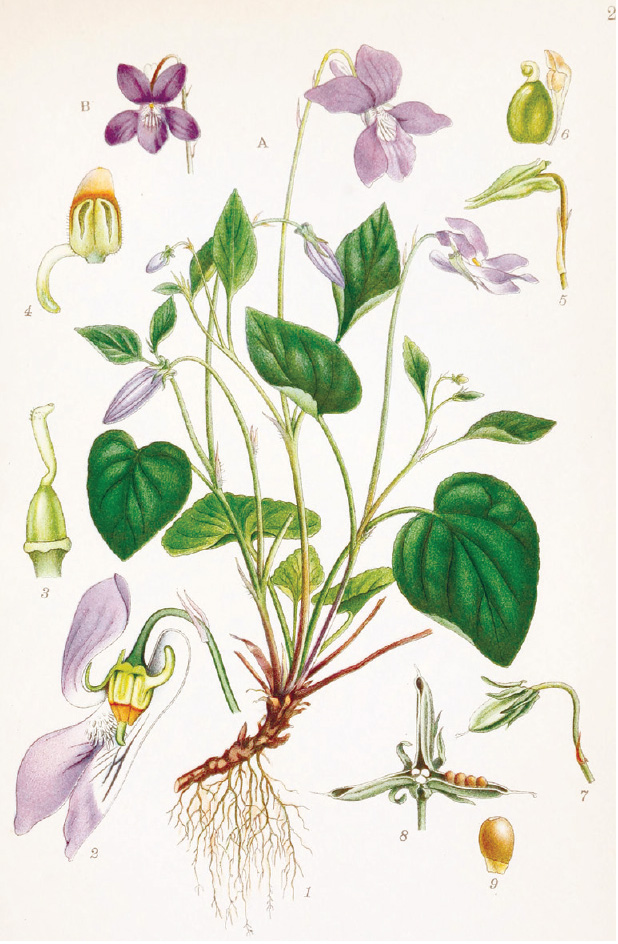

Plate 58. Violets (Viola spp.)

Plate 58. Violets (Viola spp.)

Plate 60. White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

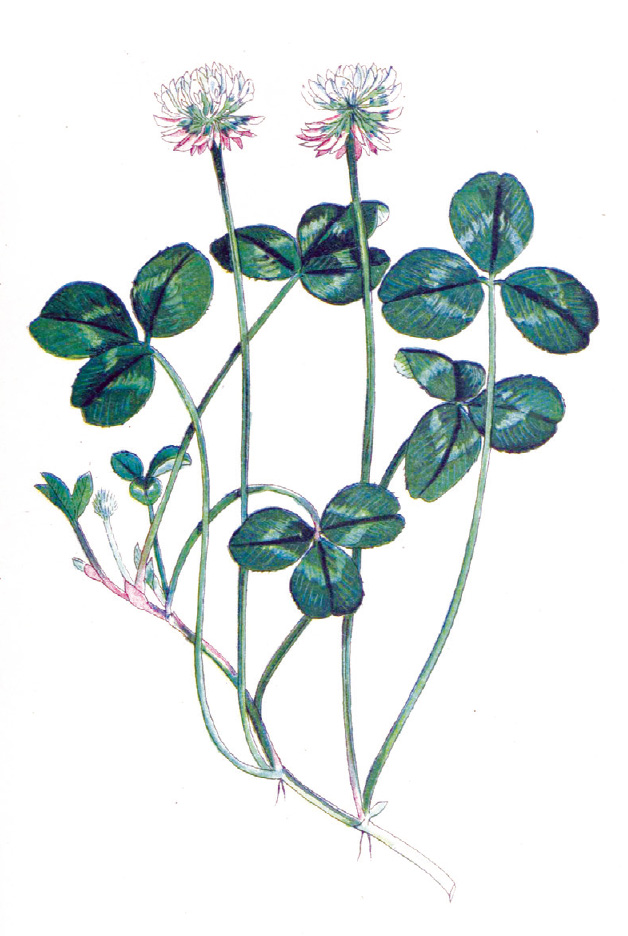

Plate 61. White Clover (Trifolium repens)

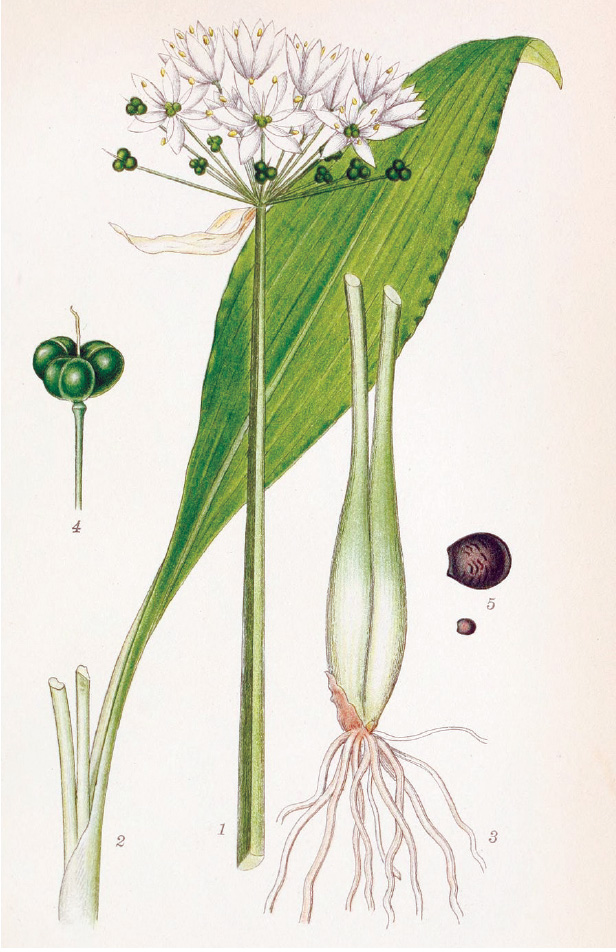

Plate 62. Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum)

Plate 63. Wild Thyme (Thymus serpyllum)

Plate 64. Willow (Salix spp.)

Plate 65. Wisteria (Wisteria sinensis)

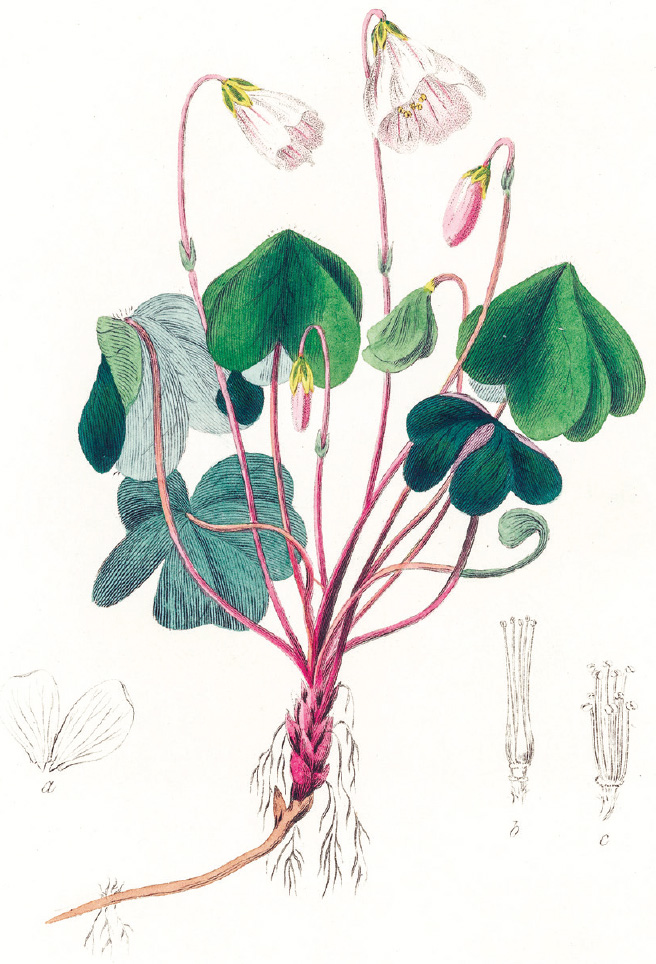

Plate 66. Wood Sorrel (Oxalis acetosella)

Plate 67. Wych Elm (Ulmus glabra)

Plate 68. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Plate 69. Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

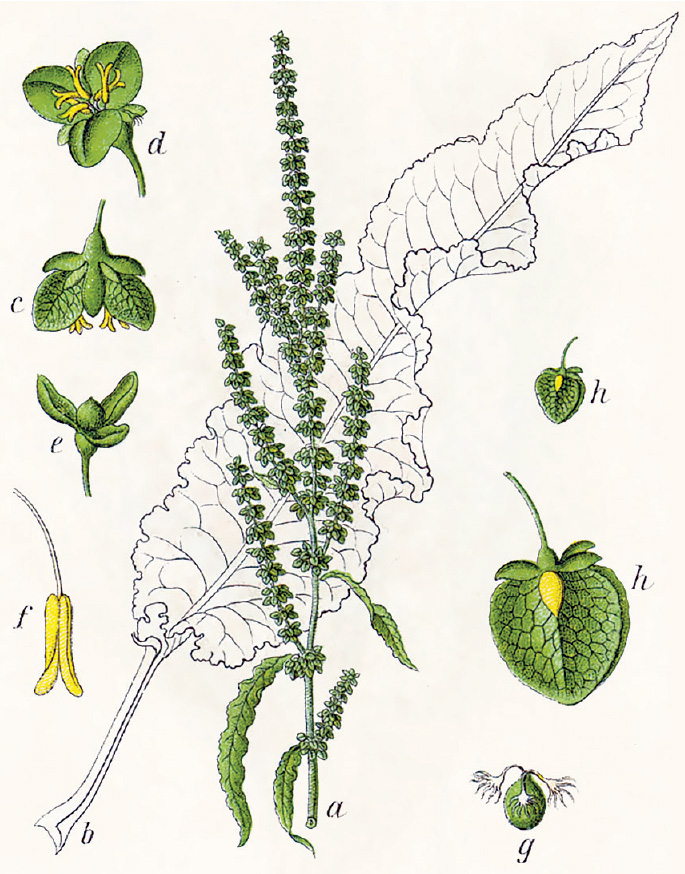

Plate 70. Yellow Dock (Rumex crispus)

Plate 71. Yew (Taxus baccata)

Each family member had their own bannock, which had been named for them as it was being made. Blessings were spoken over each individual bannock as it was formed, specifically for the person for whom it was named. If the bannock broke that meant bad luck for the intended recipient.12 Below is a recipe for an oatmeal bannock.

Oatmeal Bannock*105

Oatmeal Bannock*105

1 cup organic oatmeal

¼ cup plain organic flour

¼ teaspoon sea salt

1 teaspoon baking soda

½ cup buttermilk†106

Preheat your gridle. It is hot enough when flour sprinkled on it takes only a few seconds to brown.

Put the oatmeal, flour, and salt into a large bowl and mix well.

Put the buttermilk into a small bowl, add the teaspoon of baking soda, and mix briskly.

Add the buttermilk mixture to the dry ingredients and bring together into a soft dough. Work quickly, as the baking soda will be activated by the buttermilk. Be careful not to overwork the mixture.

Roll the mixture out on a lightly floured surface to a thickness of about ½ inch. Cut it into a round (cut around a suitably sized plate).

Dust the gridle with a small amount of flour and put on the round of dough to cook. Turn the bannock over when the underside starts to brown.

You need take care when baking bannocks because the Fairy folk may come into your house if you are not careful. To prevent this from happening put a hole in the last cake or break a piece off it or put a live coal on top of it. If you don’t do these things the Fairy folk will sing the following:

Little cake

Without gap or fissure,

Rise and let us in!13

. . . and they will be in!

Following is a recipe for making a caudle from Eliza Smith’s Compleat Housewife, 1742.

A fine Caudle: Take a Pint of Milk, turn it with Sack;*107 then strain it, and when ’tis cold, put it in a Skillet, with Mac,†108 Nutmeg, and some white Bread sliced; let all these boil, then beat the Yolks of four or five Eggs, the Whites of two, and thicken your Caudle, stirring it all one Way for fear it curdle; let it warm together, then take it off, and sweeten it to your Taste.14

Traditional Beltaine Customs in Other Countries

The people of the British Isles are not the only ones to hold celebrations on the last evening of April or the first day of May. Many other countries throughout the world have their own customs and purposes for performing spring rites at this time.

May Eve in Germany

Walpurgisnacht is the German name for Beltaine Eve, April 30, named for Saint Walpurga, the Saxon Christian woman whose name was grafted onto the Witches’ spring festival of Hexennacht. The niece of Saint Boniface, who missionized the Frankish empire, Walpurga was sent to Mainz as a missionary and was later named abbess of a convent in Heidenheim, where she baptized converted Pagans.

Walpurgisnacht is the night when Witches fly in from all over Germany on a goat, pitchfork, or broomstick to a summit in the Harz mountains to dance around bonfires. The place where they convene is called the “Hexentanzplatz” (dancing place of the Witches) at Blocksberg Hill, a high peak that is often shrouded in clouds.

In pre-Christian times these spring rituals were joyful festivals. In later Christian times they morphed into rites designed to scare away the evil Spirits and Witches and the forces of cold weather, snow, and darkness that were trying to stop the Queen of Spring from entering the land. Loud noise was said to do the trick, so starting at twilight men and boys would bang away on pots and pans and shoot gunfire into the sky. Chanting loudly and banging boards against houses added to the cacophony. Huge bonfires were lit to keep Witches away.

Offerings of bread, butter, and honey were left in the fields as offerings for phantom hounds. Cowbells were blessed and stable doors locked and hung with three crosses for extra protection. Billy goats and broomsticks had to be hidden so that Witches would not steal and ride them. Socks were left in a cross formation on children’s beds. Pentagrams were placed over entrances, and salt was spread along thresholds. Rue and Saint John’s Wort were burned to protect the house from sorcery.

Old brooms and household objects were burned in bonfires as were straw men, symbolic of bad luck, sickness, and disease. Children gathered bunches of Juniper, Hawthorn, Ash, and Elder to hang around the house and barn as protective charms. At dawn the women would bathe their faces in dew from a Hawthorn tree.15

As with Samhain/Halloween this was a “mischief night” when children and teenagers liked to play tricks. This has continued into modern times. Nowadays children and teenagers may ring doorbells and run off; spread mustard on door handles; hide floor mats, flower pots, and trash cans that have been left out; remove garden gates; or wrap cars in toilet paper. The more ambitious might even hide drainage covers from roads or move street signs.

Rain on May Eve was considered a very good omen, and on the morning of May 1 a Fir tree with its lower branches removed was hung with ribbons, sausages, pretzels, and wooden figures depicting various trades and the community’s hope for a prosperous spring.16

As with many other Pagan festivals, once the church took over and reconstituted the ancient observance, the people were able to simultaneously celebrate both the Christian and Pagan holy day without fear of persecution. They could dance the bonfires on the feast day of Saint Walpurga, just as their Pagan ancestors had always done.

May Eve in Sweden

The Swedish observance of Walpurga’s Night is called “Valborgsmässoafton.” In medieval times the fiscal year ended on April 30, giving merchants and craftsmen a reason to party. Today local groups organize celebrations in villages with bonfires and singing. Large bonfires are also lit on hills, which was originally done to scare off predators as the herds were brought up to their summer pastures.

Young people gather greenery at dusk to decorate houses and are paid in eggs. Exams are finished and students sing songs to welcome spring. May Day breakfast includes champagne and strawberries, and families gather in parks to picnic and enjoy alcoholic drinks.17

May Eve in Finland

In Finland the spring festival is called “Vappu” (First of May) and involves drinking sparkling wine and picnics with the family. A drink called sima, a type of mead, is also popular on the day. A carnival-like atmosphere prevails, especially among students.18

Green Week in Poland

Green Week (Zielone Swiatki), or Birch Week, takes place from mid-May to early June in Poland. It is a pre-Christian, Slavic spring rite that celebrates the newborn vegetation and honors the return of green leaves to the tree branches.

The Birch tree is seen as a female symbol of youth and the fires of life. Houses and shrines are decorated with Birch leaves, herbs, and flowers and ritually swept with a Birch branch, and Sweet Flag is scattered on floors as protection from evil influences.

Cattle are crowned with wreaths of flowers and purified with incense. Eggs are rolled on the sides of cows and of people to promote fertility. Bonfires are built and attended with singing and dancing, and the boundaries of the farm are walked with burning torches as a form of ritual purification.

Another old name for this celebration is the Stado (herd) festival, a feast in honor of the ancestors and the old Slavic Gods and Goddesses featuring singing, dancing, and sport competitions. A swiatki is a wooden sculpture placed in outdoor shrines, in the hollow of a tree, or at a crossroad. Crossroads were once known as places of power where divinations and invocations took place. In former days the statues would have depicted the ancient Slavic Gods; these days the statues are most often of Jesus or Mary and are decorated with greenery for the duration of the celebrations.

During Green Week a gaik, which is a small Pine tree or a symbolic tree made of Pine branches and decorated with ribbons, flowers, bells and other meaningful trinkets, is held by a girl or a woman who walks around the neighborhood singing about the arrival of spring.

Gaik is a diminutive of the word gaj, meaning “grove,” and refers to the sacred Pagan groves of ancient times. By circling the neighborhood with a gaik, the woman is bringing the blessings of the tree Spirits and the sacred grove to the village.19

May Eve in Other European Areas

The Czechs, Dutch, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Slovenians all celebrate May Eve with bonfires and dancing to drive away the cold of winter and to welcome spring. This night of Witches festival is called Heksennacht in the Netherlands and Volbriöö in Estonia.20

In Lithuania and Latvia it is known as Walpurga’s Night—or “Valpurgijos naktis” and “Valpurģi,” respectively—and in the Czech Republic it is called either “Čarodějnice” (Witches’ Night) or “Valpuržina noc” (Walpurga’s Night).21

The Czechs light huge bonfires on hilltops, and a large plume of smoke is seen as a good omen as it signifies a Witch flying away. May 1 is also a day dedicated to lovers, and women are kissed under a blooming Cherry tree.

Estonians like to dress as Witches for the day and wander the streets in celebration.

May Day in Puritan New England

We have a May Day tradition here in New England, thanks to Thomas Morton of Devonshire, England, a man with delightfully Pagan sensibilities. Morton was a well-educated lawyer and freethinker who arrived in the colonies in 1624 as part of a company that traded with Native Americans for furs.

Morton reported that there were two kinds of people in the colony: Christians and infidels. He found the infidels to be “most full of humanity and more friendly.”22

Morton battled with the Puritans of Plymouth Plantation for twenty years and eventually founded his own community called Mount Wollaston. But in 1626 he left Wollaston because he disagreed with their practice of selling indentured servants into slavery. Organizing a rebellion of the remaining indentured servants, he went on to create yet another new community called Merrymount.

The Puritans were disgusted to learn that the inhabitants of Merrymount lived in peaceful harmony with the local Algonquian and that they were even cohabiting with Native American females. To make matters worse, some Puritans fled the strictness and starvation of Plymouth Plantation to join Morton.

On May 1, 1627, Merrymount held a huge May Day celebration, one that Morton hoped would bring in more Native brides. There was plentiful beer and a Maypole, which enraged the Puritans.

The next year a second May Day celebration was held, and this time Myles Standish, the English military adviser for the Plymouth colony, captured Morton and put him in chains. There was little resistance; Morton said it was because his people at Merrymount were so peaceful, while Governor Bradford said it was because they were too drunk to fight back.

Morton was shipped back to England and that winter desperate and hungry Puritans raided Merrymount’s food stores and chopped up the infamous Maypole.

Morton returned to Merrymount in 1629 and found that most of the Natives had died from disease. In 1630 the Puritans arrested him again and burned what was left of Merrymount. Morton went back to England. In later years other rebels and freethinkers returned to Merrymount, which was renamed Wollaston and still exists to this day as a neighborhood in the city of Quincy, Massachusetts.23

Imagine how different the history of the United States might have been if we had adopted the friendly and cooperative philosophy of Thomas Morton instead of the hardline religion and racism of the Puritans!