The Indo-European homeland is like the Lost Dutchman’s Mine, a legend of the American West, discovered almost everywhere but confirmed nowhere. Anyone who claims to know its real location is thought to be just a little odd—or worse. Indo-European homelands have been identified in India, Pakistan, the Himalayas, the Altai Mountains, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, the Balkans, Turkey, Armenia, the North Caucasus, Syria/Lebanon, Germany, Scandinavia, the North Pole, and (of course) Atlantis. Some homelands seem to have been advanced just to provide a historical precedent for nationalist or racist claims to privileges and territory. Others are enthusiastically zany. The debate, alternately dryly academic, comically absurd, and brutally political, has continued for almost two hundred years.1

This chapter lays out the linguistic evidence for the location of the Proto-Indo-European homeland. The evidence will take us down a well-worn path to a familiar destination: the grasslands north of the Black and Caspian Seas in what is today Ukraine and southern Russia, also known as the Pontic-Caspian steppes (figure 5.1). Certain scholars, notably Marija Gimbutas and Jim Mallory, have argued persuasively for this homeland for the last thirty years, each using criteria that differ in some significant details but reaching the same end point for many of the same reasons.2 Recent discoveries have strengthened the Pontic-Caspian hypothesis so significantly, in my opinion, that we can reasonably go forward on the assumption that this was the homeland.

At the start I should acknowledge some fundamental problems. Many of my colleagues believe that it is impossible to identify any homeland for Proto-Indo-European, and the following are their three most serious concerns.

Figure 5.1 The Proto-Indo-European homeland between about 3500–3000 BCE.

Problem #1. Reconstructed Proto-Indo-European is merely a linguistic hypothesis, and hypotheses do not have homelands.

This criticism concerns the “reality” of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European, a subject on which linguists disagree. We should not imagine, some remind us, that reconstructed Proto-Indo-European was ever actually spoken anywhere. R.M.W. Dixon commented that if we cannot have “absolute certainty” about the grammatical type of a reconstructed language, it throws doubt over “every detail of the putative reconstruction.”3 But this is an extreme demand. The only field in which we can find absolute certainty is religion. In all other activities we must be content with the best (meaning both the simplest and the most data-inclusive) interpretation we can advance, given the data as they now stand. After we accept that this is true in all secular inquiries, the question of whether Proto-Indo-European can be thought of as “real” boils down to three sharper criticisms:

Reconstructed Proto-Indo-European is fragmentary (most of the language it represents never will be known).

The part that is reconstructed is homogenized, stripped of many of the peculiar sounds of its individual dialects, by the comparative method (although in reconstructed Proto-Indo-European some evidence of dialect survives).

Proto-Indo-European is not a snapshot of a moment in time but rather is “timeless”: it averages together centuries or even millennia of development. In that sense, it is an accurate picture of no single era in language history.

These seem to be serious criticisms. But if their effect is to make Proto-Indo-European a mere fantasy, then the English language as presented in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary is a fantasy, too. My dictionary contains the English word ombre (a card game popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) as well as hard disk (a phrase that first appeared in the 1978 edition). So its vocabulary averages together at least three hundred years of the language. And its phonology, the “proper” pronuciation it describes, is quite restricted. Only one pronunciation is given for hard disk, and it is not the Bostonian hard [haahd]. The English of Merriam-Webster has never been spoken in its entirety by any one person. Nevertheless we all find it useful as a guide to real spoken English. Reconstructed Proto-Indo-European is similar, a dictionary version of a language. It is not, in itself, a real language, but it certainly refers to one. And we should remember that Sumerian cuneiform documents and Egyptian hieroglyphs present exactly the same problems as reconstructed Proto-Indo-European: the written scripts do not clearly indicate every sound, so their phonology is uncertain; they contain only royal or priestly dialects; and they might preserve archaic linguistic forms, like Church Latin. They are not, in themselves, real languages; they only refer to real languages. Reconstructed Proto-Indo-European is not so different from cuneiform Sumerian.

If Proto-Indo-European is like a dictionary, then it cannot be “timeless.” A dictionary is easily dated by its most recent entries. A dictionary containing the term hard disk is dated after 1978 in just the way that the wagon terminology in Proto-Indo-European dates it to a time after about 4000–3500 BCE. It is more dangerous to use negative information as a dating tool, since many words that really existed in Proto-Indo-European will never be reconstructed, but it is at least interesting that Proto-Indo-European does not contain roots for items like spoke, iron, cotton, chariot, glass, or coffee—things that were invented after the evolution and dispersal of the daughter languages, or, in the metaphor we are using, after the dictionary was printed.

Of course, the dictionary of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European is much more tattered than my copy of Merriam-Webster’s. Many pages have been torn out, and those that survive are obscured by the passage of time. The problem of the missing pages bothers some linguists the most. A reconstructed proto-language can seem a disappointing skeleton with a lot of bones missing and the placement of others debated between experts. The complete language the skeleton once supported certainly is a theoretical construct. So is the flesh-and-blood image of any dinosaur. Nevertheless, like the paleontologist, I am happy to have even a fragmentary skeleton. I think of Proto-Indo-European as a partial grammar and a partial set of pronunciation rules attached to the abundant fragments of a very ancient dictionary. To some linguists, that might not add up to a “real” language. But to an archaeologist it is more valuable than a roomful of potsherds.

Problem #2. The entire concept of “reconstructed Proto-Indo-European” is a fantasy: the similarities between the Indo-European languages could just as well have come about by gradual convergence over thousands of years between languages that had very different origins.

This is a more radical criticism then the first one. It proposes that the comparative method is a rigged game that automatically produces a proto-language as its outcome. The comparative method is said to ignore the linguistic changes that result from inter-language borrowing and convergence. Gradual convergence between originally diverse tongues, these scholars claim, might have produced the similarities between the Indo-European languages.4 If this were true or even probable there would indeed be no reason to pursue a single parent of the Indo-European languages. But the Russian linguist who inspired this line of questioning, Nikolai S. Trubetzkoy, worked in the 1930s before linguists really had the tools to investigate his startling suggestion.

Since then, quite a few linguists have taken up the problem of convergence between languages. They have greatly increased our understanding of how convergence happens and what its linguistic effects are. Although they disagree strongly with one another on some subjects, all recent studies of convergence accept that the Indo-European languages owe their essential similarities to descent from a common ancestral language, and not to convergence.5 Of course, some convergence has occurred between neighboring Indo-European languages—it is not a question of all or nothing—but specialists agree that the basic structures that define the Indo-European language family can only be explained by common descent from a mother tongue.

There are three reasons for this unanimity. First, the Indo-European languages are the most thoroughly studied languages in the world—simply put, we know a lot about them. Second, linguists know of no language where bundled similarities of the kinds seen among the Indo-European languages have come about through borrowing or convergence between languages that were originally distinct. And, finally, the features known to typify creole languages—languages that are the product of convergence between two or more originally distinct languages—are not seen among the Indo-European languages. Creole languages are characterized by greatly reduced noun and pronoun inflections (no case or even single/plural markings); the use of pre-verbal particles to replace verb tenses (“we bin get” for “we got”); the general absence of tense, gender, and person inflections in verbs; a severely reduced set of prepositions; and the use of repeated forms to intensify adverbs and adjectives. In each of these features Proto-Indo-European was the opposite of a typical creole. It is not possible to classify Proto-Indo-European as a creole by any of the standards normally applied to creole languages.6

Nor do the Indo-European daughter languages display the telltale signs of creoles. This means that the Indo-European vocabularies and grammars replaced competing languages rather than creolizing with them. Of course, some back-and-forth borrowing occurred—it always does in cases of language contact—but superficial borrowing and creolization are very different things. Convergence simply cannot explain the similarities between the Indo-European languages. If we discard the mother tongue, we are left with no explanation for the regular correspondences in sound, morphology, and meaning that define the Indo-European language family.

Problem #3. Even if there was a homeland where Proto-Indo-European was spoken, you cannot use the reconstructed vocabulary to find it because the reconstructed vocabulary is full of anachronisms that never existed in Proto-Indo-European.

This criticism, like the last one, reflects concerns about recent inter-language borrowing, focused here on just the vocabulary. Of course, many borrowed words are known to have spread through the Indo-European daughter languages long after the period of the proto-language—recent examples are coffee (borrowed from Arabic through Turkish) and tobacco (from Carib). The words for these items sound alike and have the same meanings in the different Indo-European languages, but few linguists would mistake them for ancient inherited words. Their phonetics are non—Indo-European, and their forms in the daughter branches do not represent what would be expected from inherited roots.7 Terms like coffee are not a significant source of contamination.

Historical linguists do not ignore borrowing between languages. An understanding of borrowing is essential. For example, subtle inconsistencies embedded within German, Greek, Celtic, and other languages, including such fleeting sounds as the word-initial [kn-] (knob) can be identified as phonetically uncharacteristic of Indo-European. These fragments from extinct non—Indo-European languages are preserved only because they were borrowed. They can help us create maps of pre—Indo-European place-names, like the places ending with [-ssos] or [-nthos] (Corinthos, Knossos, Parnassos), borrowed into Greek and thought to show the geographic distribution of the pre-Greek language(s) of the Aegean and western Anatolia. Borrowed non—Indo-European sounds also were used to reconstruct some aspects of the long-extinct non—Indo-European languages of northern and eastern Europe. All that is left of these tongues is an occasional word or sound in the Indo-European languages that replaced them. Yet we can still identify their fragments in words borrowed thousands of years ago.8

Another regular use of borrowing is the study of “areal” features like Sprachbunds. A Sprachbund is a region where several different languages are spoken interchangeably in different situations, leading to their extensive borrowing of features. The most famous Sprachbund is in southeastern Europe, where Albanian, Bulgarian, Serbo-Croat, and Greek share many features, with Greek as the dominant element, probably because of its association with the Greek Orthodox Church. Finally, borrowing is an ever-present factor in any study of “genetic” relatedness. Whenever a linguist tries to decide whether cognate terms in two daughter languages are inherited from a common source, one alternative that must be excluded is that one language borrowed the term from the other. Many of the methods of comparative linguistics depend on the accurate identification of borrowed words, sounds, and morphologies.

When a root of similar sound and similar meaning shows up in widely separated Indo-European languages (including an ancient language), and phonological comparison of its forms yields a single ancestral root, that root term can be assigned with some confidence to the Proto-Indo-European vocabulary. No single reconstructed root should be used as the basis for an elaborate theory about Proto-Indo-European culture, but we do not need to work with single roots; we have clusters of terms with related meanings. At least fifteen hundred unique Proto-Indo-European roots have been reconstructed, and many of these unique roots appear in multiple reconstructed Proto-Indo-European words, so the total count of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European terms is much greater than fifteen hundred. Borrowing is a specific problem that affects specific reconstructed roots, but it does not cancel the usefulness of a reconstructed vocabulary containing thousands of terms.

The Proto-Indo-European homeland is not a racist myth or a purely theoretical fantasy. A real language lies behind reconstructed Proto-Indo-European, just as a real language lies behind any dictionary. And that language is a guide to the thoughts, concerns, and material culture of real people who lived in a definite region between about 4500 and 2500 BCE. But where was that region?

Regardless of where they ended up, most investigators of the Indo-European problem all started out the same way. The first step is to identify roots in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European vocabulary referring to animal and plant species or technologies that existed only in certain places at particular times. The vocabulary itself should point to a homeland, at least within broad limits. For example, imagine that you were asked to identify the home of a group of people based only on the knowledge that a linguist had recorded these words in their normal daily speech:

You could identify them fairly confidently as residents of the American southwest, probably during the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries (six-gun and the absence of words for trucks, cars, and highways are the best chronological indicators). They probably were cowboys—or pretending to be. Looking closer, the combination of armadillo, sagebrush, and cactus would place them in west Texas, New Mexico, or Arizona.

Linguists have long tried to find animal or plant names in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European vocabulary referring to species that lived in just one part of the world. The reconstructed Proto-Indo-European term for salmon, *lók*s, was once famous as definite proof that the “Aryan” homeland lay in northern Europe. But animal and tree names seem to narrow and broaden in meaning easily. They are even reused and recycled when people move to a new environment, as English colonists used robin for a bird in the Americas that was a different species from the robin of England. The most specific meaning most linguists would now feel comfortable ascribing to the reconstructed term *lók*s- is “trout-like fish.” There are fish like that in the rivers across much of northern Eurasia, including the rivers flowing into the Black and Caspian Seas. The reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root for beech has a similar history. Because the copper beech, Fagus silvatica, did not grow east of Poland, the Proto-Indo-European root *bháo - was once used to support a northern or western European homeland. But in some Indo-European languages the same root refers to other tree species (oak or elder), and in any case the common beech (Fagus orientalis) grows also in the Caucasus, so its original meaning is unclear. Most linguists at least agree that the fauna and flora designated by the reconstructed vocabulary are temperate-zone types (birch, otter, beaver, lynx, bear, horse), not Mediterranean (no cypress, olive, or laurel) and not tropical (no monkey, elephant, palm, or papyrus). The roots for horse and bee are most helpful.

- was once used to support a northern or western European homeland. But in some Indo-European languages the same root refers to other tree species (oak or elder), and in any case the common beech (Fagus orientalis) grows also in the Caucasus, so its original meaning is unclear. Most linguists at least agree that the fauna and flora designated by the reconstructed vocabulary are temperate-zone types (birch, otter, beaver, lynx, bear, horse), not Mediterranean (no cypress, olive, or laurel) and not tropical (no monkey, elephant, palm, or papyrus). The roots for horse and bee are most helpful.

Bee and honey are very strong reconstructions based on cognates in most Indo-European languages. A derivative of the term for honey, *medhu-, was also used for an intoxicating drink, mead, that probably played a prominent role in Proto-Indo-European rituals. Honeybees were not native east of the Ural Mountains, in Siberia, because the hardwood trees (lime and oak, particularly) that wild honeybees prefer as nesting sites were rare or absent east of the Urals. If bees and honey did not exist in Siberia, the homeland could not have been there. That removes all of Siberia and much of northeastern Eurasia from contention, including the Central Asian steppes of Kazakhstan. The horse, *ek*wo-, is solidly reconstructed and seems also to have been a potent symbol of divine power for the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Although horses lived in small, isolated pockets throughout prehistoric Europe, the Caucasus, and Anatolia between 4500 and 2500 BCE, they were rare or absent in the Near East, Iran, and the Indian subcontinent. They were numerous and economically important only in the Eurasian steppes. The term for horse removes the Near East, Iran, and the Indian subcontinent from serious contention, and encourages us to look closely at the Eurasian steppes. This leaves temperate Europe, including the steppes west of the Urals, and the temperate parts of Anatolia and the Caucasus Mountains.9

The speakers of Proto-Indo-European were farmers and stockbreeders: we can reconstruct words for bull, cow, ox, ram, ewe, lamb, pig, and piglet. They had many terms for milk and dairy foods, including sour milk, whey, and curds. When they led their cattle and sheep out to the field they walked with a faithful dog. They knew how to shear wool, which they used to weave textiles (probably on a horizontal band loom). They tilled the earth (or they knew people who did) with a scratch-plow, or ard, which was pulled by oxen wearing a yoke. There are terms for grain and chaff, and perhaps for furrow. They turned their grain into flour by grinding it with a hand pestle, and cooked their food in clay pots (the root is actually for cauldron, but that word in English has been narrowed to refer to a metal cooking vessel). They divided their possessions into two categories: movables and immovables; and the root for movable wealth (*peku-, the ancestor of such English words as pecuniary) became the term for herds in general.10 Finally, they were not averse to increasing their herds at their neighbors’ expense, as we can reconstruct verbs that meant “to drive cattle,” used in Celtic, Italic, and Indo-Iranian with the sense of cattle raiding or “rustling.”

What was social life like? The speakers of Proto-Indo-European lived in a world of tribal politics and social groups united through kinship and marriage. They lived in households (*dómha), containing one or more families (*génh1es-) organized into clans (*wei -), which were led by clan leaders, or chiefs (*weik-potis). They had no word for city. Households appear to have been male-centered. Judging from the reconstructed kin terms, the important named kin were predominantly on the father’s side, which suggests patrilocal marriages (brides moved into the husband’s household). A group identity above the level of the clan was probably tribe (*h4erós), a root that developed into Aryan in the Indo-Iranian branch.11

-), which were led by clan leaders, or chiefs (*weik-potis). They had no word for city. Households appear to have been male-centered. Judging from the reconstructed kin terms, the important named kin were predominantly on the father’s side, which suggests patrilocal marriages (brides moved into the husband’s household). A group identity above the level of the clan was probably tribe (*h4erós), a root that developed into Aryan in the Indo-Iranian branch.11

The most famous definition of the basic divisions in Proto-Indo-European society was the tripartite scheme of Georges Dumézil, who suggested that there was a fundamental three-part division between the ritual specialist or priest, the warrior, and the ordinary herder/cultivator. Colors might have been associated with these three roles: white for the priest, red for the warrior, and black or blue for the herder/cultivator; and each role might have been assigned a specific type of ritual/legal death: strangulation for the priest, cutting/stabbing for the warrior, and drowning for the herder/cultivator. A variety of other legal and ritual distinctions seem to have applied to these three identities. It is unlikely that Dumézil’s three divisions were groups with a limited membership. Probably they were something much less defined, like three age grades through which all males were expected to pass—perhaps herders (young), warriors (older), and lineage elders/ritual leaders (oldest), as among the Maasai in east Africa. The warrior category was regarded with considerable ambivalence, often represented in myth by a figure who alternated between a protector and a berserk murderer who killed his own father (Hercules, Indra, Thor). Poets occupied another respected social category. Spoken words, whether poems or oaths, were thought to have tremendous power. The poet’s praise was a mortal’s only hope for immortality.

The speakers of Proto-Indo-European were tribal farmers and stockbreeders. Societies like this lived across much of Europe, Anatolia, and the Caucasus Mountains after 6000 BCE. But regions where hunting and gathering economies persisted until after 2500 BCE are eliminated as possible homelands, because Proto-Indo-European was a dead language by 2500 BCE. The northern temperate forests of Europe and Siberia are excluded by this stockbreeders-before-2500 BCE rule, which cuts away one more piece of the map. The Kazakh steppes east of the Ural Mountains are excluded as well. In fact, this rule, combined with the exclusion of tropical regions and the presence of honeybees, makes a homeland anywhere east of the Ural Mountains unlikely.

The possible homeland locations can be narrowed further by identifying the neighbors. The neighbors of the speakers of Proto-Indo-European can be identified through words and morphologies borrowed between Proto-Indo-European and other language families. It is a bit risky to discuss borrowing between reconstructed proto-languages—first, we have to reconstruct a phonological system for each of the proto-languages, then identify roots of similar form and meaning in both proto-languages, and finally see if the root in one proto-language meets all the expectations of a root borrowed from the other. If neighboring proto-languages have the same roots, reconstructed independently, and one root can be explained as a predictable outcome of borrowing from the other, then we have a strong case for borrowing. So who borrowed words from, or loaned words into, Proto-Indo-European? Which language families exhibit evidence of early contact and interchange with Proto-Indo-European?

By far the strongest linkages can be seen with Uralic. The Uralic languages are spoken today in northern Europe and Siberia, with one southern off-shoot, Magyar, in Hungary, which was conquered by Magyar-speaking invaders in the tenth century. Uralic, like Indo-European, is a broad language family; its daughter languages are spoken across the northern forests of Eurasia from the Pacific shores of northeastern Siberia (Nganasan, spoken by tundra reindeer herders) to the Atlantic and Baltic coasts (Finnish, Estonian, Saami, Karelian, Vepsian, and Votian). Most linguists divide the family at the root into two super-branches, Finno-Ugric (the western branch) and Samoyedic (the eastern), although Salminen has argued that this binary division is based more on tradition than on solid linguistic evidence. His alternative is a “flat” division of the language family into nine branches, with Samoyedic just one of the nine.12

The homeland of Proto-Uralic probably was in the forest zone centered on the southern flanks of the Ural Mountains. Many argue for a homeland west of the Urals and others argue for the east side, but almost all Uralic linguists and Ural-region archaeologists would agree that Proto-Uralic was spoken somewhere in the birch-pine forests between the Oka River on the west (around modern Gorky) and the Irtysh River on the east (around modern Omsk). Today the Uralic languages spoken in this core region include, from west to east, Mordvin, Mari, Udmurt, Komi, and Mansi, of which two (Udmurt and Komi) are stems on the same branch (Permian). Some linguists have proposed homelands located farther east (the Yenisei River) or farther west (the Baltic), but the evidence for these extremes has not convinced many.13

The reconstructed Proto-Uralic vocabulary suggests that its speakers lived far from the sea in a forest environment. They were foragers who hunted and fished but possessed no domesticated plants or animals except the dog. This correlates well with the archaeological evidence. In the region between the Oka and the Urals, the Lyalovo culture was a center of cultural influences and interchanges among forest-zone forager cultures, with inter-cultural connections extending from the Baltic to the eastern slopes of the Urals during approximately the right period, 4500–3000 BCE.

The Uralic languages show evidence of very early contact with Indo-European languages. How that contact is interpreted is a subject of debate. There are three basic positions. First, the Indo-Uralic hypothesis suggests that the morphological linkages between the two families are so deep (shared pronouns), and the kinds of shared vocabulary so fundamental (words for water and name), that Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic must have inherited these shared elements from some very ancient common linguistic parent—perhaps we might call it a “grandmother-tongue.” The second position, the early loan hypothesis, argues that the forms of the shared proto-roots for terms like name and water, as reconstructed in the vocabularies of both Proto-Uralic and Proto-Indo-European, are much too similar to reflect such an ancient inheritance. Inherited roots should have undergone sound shifts in each developing family over a long period, but these roots are so similar that they can only be explained as loans from one proto-language into the other—and, in all cases, the loans went from Proto-Indo-European into Proto-Uralic.14 The third position, the late loan hypothesis, is the one perhaps encountered most frequently in the general literature. It claims that there is little or no convincing evidence for borrowings even as old as the respective proto-languages; instead, the oldest well-documented loans should be assigned to contacts between Indo-Iranian and late Proto-Uralic, long after the Proto-Indo-European period. Contacts with Indo-Iranian could not be used to locate the Proto-Indo-European homeland.

At a conference dedicated to these subjects held at the University of Helsinki in 1999, not one linguist argued for a strong version of the late-loan hypothesis. Recent research on the earliest loans has reinforced the case for an early period of contact at least as early as the level of the proto-languages. This is well reflected in vocabulary loans. Koivulehto discussed at least thirteen words that are probable loans from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) into Proto-Uralic (P-U):

to give or to sell; P-U *mexe from PIE *h2mey-gw- ‘to change’, ‘exchange’

to bring, lead, or draw; P-U *wetä- from PIE *wedh-e/o- ‘to lead’, ‘to marry’, ‘to wed’

to wash; P-U *mośke- from PIE *mozg-eye/o- ‘to wash’, ‘to submerge’

to fear; P-U *pele- from PIE *pelh1- ‘to shake’, ‘cause to tremble’

to plait, to spin; P-U *puna- from PIE *pn.H-e/o- ‘to plait’, ‘to spin’

to walk, wander, go; P-U *kulke- from PIE *kwelH-e/o- ‘it/he/she walks around’, ‘wanders’

to drill, to bore; P-U *pura- from PIE *bh H- ‘to bore’, ‘to drill’

H- ‘to bore’, ‘to drill’

shall, must, to have to; P-U *kelke- from PIE *skelH- ‘to be guilty’, ‘shall’, ‘must’

long thin pole; P-U *śalka- from PIE *ghalgho- ‘well-pole’, ‘gallows’, ‘long pole’

merchandise, price; P-U *wosa from PIE *wosā ‘merchandise’, ‘to buy’

water; P-U *wete from PIE *wed-er/en, ‘water’, ‘river’

sinew; P-U *sōne from PIE *sneH(u)- ‘sinew’

name; P-U *nime- from PIE *h3neh3mn- ‘name’

Another thirty-six words were borrowed from differentiated Indo-European daughter tongues into early forms of Uralic prior to the emergence of differentiated Indic and Iranian—before 1700–1500 BCE at the latest. These later words included such terms as bread, dough, beer, to winnow, and piglet, which might have been borrowed when the speakers of Uralic languages began to adopt agriculture from neighboring Indo-European—speaking farmers and herders. But the loans between the proto-languages are the important ones bearing on the location of the Proto-Indo-European homeland. And that they are so similar in form does suggest that they were loans rather than inheritances from some very ancient common ancestor.

This does not mean that there is no evidence for an older level of shared ancestry. Inherited similarities, reflected in shared pronoun forms and some noun endings, might have been retained from such a common ancestor. The pronoun and inflection forms shared by Indo-European and Uralic are the following:

| Proto-Uralic | Proto-Indo-European | |

|---|---|---|

| *te-nä | (thou) | *ti (?) |

| *te | (you) | *ti (clitic dative) |

| *me-nä | (I) | *mi |

| *tä-/to- | (this/that) | *te-/to- |

| *ke-, ku- | (who, what) | *kwe/o- |

| *-m | (accusative sing.) | *-m* |

| *-n | (genitive plural) | *-om |

These parallels suggest that Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic shared two kinds of linkages.15 One kind, revealed in pronouns, noun endings, and shared basic vocabulary, could be ancestral: the two proto-languages shared some quite ancient common ancestor, perhaps a broadly related set of intergrading dialects spoken by hunters roaming between the Carpathians and the Urals at the end of the last Ice Age. The relationship is so remote, however, that it can barely be detected. Johanna Nichols has called this kind of very deep, apparently genetic grouping a “quasistock.”16 Joseph Greenberg saw Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic as particularly close cousins within a broader set of such language stocks that he called “Eurasiatic.”

The other link between Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Uralic seems cultural: some Proto-Indo-European words were borrowed by the speakers of Proto-Uralic. Although they seem odd words to borrow, the terms to wash, price, and to give or to sell might have been borrowed through a trade jargon used between Proto-Uralic and Proto-Indo-European speakers. These two kinds of linguistic relationship—a possible common ancestral origin and inter-language borrowings—suggest that the Proto-Indo-European homeland was situated near the homeland of Proto-Uralic, in the vicinty of the southern Ural Mountains. We also know that the speakers of Proto-Indo-European were farmers and herders whose language had disappeared by 2500 BCE. The people living east of the Urals did not adopt domesticated animals until after 2500 BC. Proto-Indo-European must therefore have been spoken somewhere to the south and west of the Urals, the only region close to the Urals where farming and herding was regularly practiced before 2500 BCE.

Proto-Indo-European also had contact with the languages of the Caucasus Mountains, primarily those now classified as South Caucasian or Kartvelian, the family that produced modern Georgian. These connections have suggested to some that the Proto-Indo-European homeland should be placed in the Caucasus near Armenia or perhaps in nearby eastern Anatolia. The links between Proto-Indo-European and Kartvelian are said to appear in both phonetics and vocabulary, although the phonetic link is controversial. It depends on a brilliant but still problematic revision of the phonology of Proto-Indo-European proposed by the linguists T. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov, known as the glottalic theory.17 The glottalic theory made Proto-Indo-European phonology sound somewhat similar to that of Kartvelian, and even to the Semitic languages (Assyrian, Hebrew, Arabic) of the ancient Near East. This opened the possibility that Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Kartvelian, and Proto-Semitic might have evolved in a region where they shared certain areal phonological features. But by itself the glottalic phonology cannot prove a homeland in the Caucasus, even if it is accepted. And the glottalic phonology still has failed to convince many Indo-European linguists.18

Gamkrelidze and Ivanov have also suggested that Proto-Indo-European contained terms for panther, lion, and elephant, and for southern tree species. These animals and trees could be used to exclude a northern homeland. They also compiled an impressive list of loan words which they said were borrowed from Proto-Kartvelian and the Semitic languages into Proto-Indo-European. These relationships suggested to them that Proto-Indo-European had evolved in a place where it was in close contact with both the Semitic languages and the languages of the Southern Caucasus. They suggested Armenia as the most probable Indo-European homeland. Several archaeologists, prominently Colin Renfrew and Robert Drews, have followed their general lead, borrowing some of their linguistic arguments but placing the Indo-European homeland a little farther west, in central or western Anatolia.

But the evidence for a Caucasian or Anatolian homeland is weak. Many of the terms suggested as loans from Semitic into Proto-Indo-European have been rejected by other linguists. The few Semitic-to-Proto-Indo-European loan words that are widely accepted, words for items like silver and bull, might be words that were carried along trade and migration routes far from the Semites’ Near Eastern homeland. Johanna Nichols has shown from the phonology of the loans that the Proto-Indo-European/Proto-Kartvelian/Proto-Semitic contacts were indirect—all the loan words passed through unknown intermediaries between the known three. One intermediary is required by chronology, as Proto-Kartvelian is generally thought to have existed after Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Semitic.19

The Semitic and Caucasian vocabulary that was borrowed into Proto-Indo-European through Kartvelian therefore contains roots that belonged to some Pre-Kartvelian or Proto-Kartvelian language in the Caucasus. This language had relations, through unrecorded intermediaries, with Proto-Indo-European on one side and Proto-Semitic on the other. That is not a particularly close lexical relationship. If Proto-Kartvelian was spoken on the south side of the North Caucasus Mountain range, as seems likely, it might have been spoken by people associated with the Early Transcaucasian Culture (also known as the Kura-Araxes culture), dated about 3500–2200 BCE. They could have had indirect relations with the speakers of Proto-Indo-European through the Maikop culture of the North Caucasus region. Many experts agree that Proto-Indo-European shared some features with a language ancestral to Kartvelian but not necessarily through a direct face-to-face link. Relations with the speakers of Proto-Uralic were closer.

So who were the neighbors? Proto-Indo-European exhibits strong links with Proto-Uralic and weaker links with a language ancestral to Proto-Kartvelian. The speakers of Proto-Indo-European lived somewhere between the Caucasus and Ural Mountains but had deeper linguistic relationships with the people who lived around the Urals.

The speakers of Proto-Indo-European were tribal farmers who cultivated grain, herded cattle and sheep, collected honey from honeybees, drove wagons, made wool or felt textiles, plowed fields at least occasionally or knew people who did, sacrificed sheep, cattle, and horses to a troublesome array of sky gods, and fully expected the gods to reciprocate the favor. These traits guide us to a specific kind of material culture—one with wagons, domesticated sheep and cattle, cultivated grains, and sacrificial deposits with the bones of sheep, cattle, and horses. We should also look for a specific kind of ideology. In the reciprocal exchange of gifts and favors between their patrons, the gods, and human clients, humans offered a portion of their herds through sacrifice, accompanied by well-crafted verses of praise; and the gods in return provided protection from disease and misfortune, and the blessings of power and prosperity. Patron-client reciprocity of this kind is common among chiefdoms, societies with institutionalized differences in prestige and power, where some clans or lineages claim a right of patronage over others, usually on grounds of holiness or historical priority in a given territory.

Knowing that we are looking for a society with a specific list of material culture items and institutionalized power distinctions is a great help in locating the Proto-Indo-European homeland. We can exclude all regions where hunter-gatherer economies survived up to 2500 BCE. That eliminates the northern forest zone of Eurasia and the Kazakh steppes east of the Ural Mountains. The absence of honeybees east of the Urals eliminates any part of Siberia. The temperate-zone flora and fauna in the reconstructed vocabulary, and the absence of shared roots for Mediterranean or tropical flora and fauna, eliminate the tropics, the Mediterranean, and the Near East. Proto-Indo-European exhibits some very ancient links with the Uralic languages, overlaid by more recent lexical borrowings into Proto-Uralic from Proto-Indo-European; and it exhibits less clear linkages to some Pre— or Proto-Kartvelian language of the Caucasus region. All these requirements would be met by a Proto-Indo-European homeland placed west of the Ural Mountains, between the Urals and the Caucasus, in the steppes of eastern Ukraine and Russia. The internal coherence of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European—the absence of evidence for radical internal variation in grammar and phonology—indicates that the period of language history it reflects was less than two thousand years, probably less than one thousand. The heart of the Proto-Indo-European period probably fell between 4000 and 3000 BCE, with an early phase that might go back to 4500 BCE and a late phase that ended by 2500 BCE.

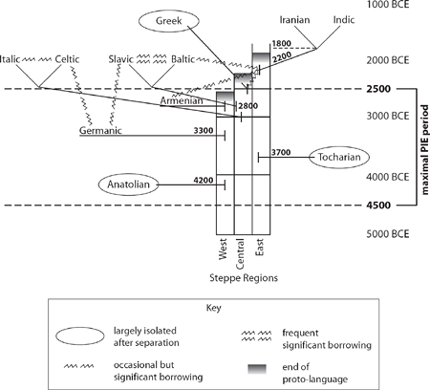

What does archaeology tell us about the steppe region between the Caucasus and the Urals, north of the Black and Caspian Seas—the Pontic-Caspian region—during this period? First, archaeology reveals a set of cultures that fits all the requirements of the reconstructed vocabulary: they sacrificed domesticated horses, cattle, and sheep, cultivated grain at least occasionally, drove wagons, and expressed institutionalized status distinctions in their funeral rituals. They occupied a part of the world—the steppes—where the sky is by far the most striking and magnificent part of the landscape, a fitting environment for people who believed that all their most important deities lived in the sky. Archaeological evidence for migrations from this region into neighboring regions, both to the west and to the east, is well established. The sequence and direction of these movements matches the sequence and direction suggested by Indo-European linguistics and geography (figure 5.2). The first identifiable migration out of the Pontic-Caspian steppes was a movement toward the west about 4200–3900 BCE that could represent the detachment of the Pre-Anatolian branch, at a time before wheeled vehicles were introduced to the steppes (see chapter 4). This was followed by a movement toward the east (about 3700–3300 BCE) that could represent the detachment of the Tocharian branch. The next visible migration out of the steppes flowed toward the west. Its earliest phase might have separated the Pre-Germanic branch, and its later, more visible phase detached the Pre-Italic and Pre-Celtic dialects. This was followed by movements to the north and east that probably established the Baltic-Slavic and Indo-Iranian tongues. The remarkable match between the archaeologically documented pattern of movements out of the steppes and that expected from linguistics is fascinating, but it has absorbed, for too long, most of the attention and debate that is directed at the archaeology of Indo-European origins. Archaeology also adds substantially to our cultural and economic understanding of the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Once the homeland has been located with linguistic evidence, the archaeology of that region provides a wholly new kind of information, a new window onto the lives of the people who spoke Proto-Indo-European and the process by which it became established and began to spread.

Figure 5.2 A diagram of the sequence and approximate dates of splits in early Indo-European as proposed in this book, with the maximal window for Proto-Indo-European indicated by the dashed lines. The dates of splits are determined by archaeological events described in chapters 11 (Anatolian) through 16 (Iranian and Indic).

Before we step into the archaeology, however, we should pause and think for a moment about the gap we are stepping across, the void between linguistics and archaeology, a chasm most Western archaeologists feel cannot be crossed. Many would say that language and material culture are completely unrelated, or are related in such changeable and complicated ways that it is impossible to use material culture to identify language groups or boundaries. If that is true, then even if we can identify the place and time of the Indo-European homeland using the reconstructed vocabulary, the link to archaeology is impossible. We cannot expect any correlation with material culture. But is such pessimism warranted? Is there no predictable, regular link between language and material culture?