A language homeland implies a bounded space of some kind. How can we define those boundaries? Can ancient linguistic frontiers be identified through archaeology?

Let us first define our terms. It would be helpful if anthropologists used the same vocabulary used in geography. According to geographers, the word border is neutral—it has no special or restricted meaning. A frontier is a specific kind of border—a transitional zone with some depth, porous to cross-border movement, and very possibly dynamic and moving. A frontier can be cultural, like the Western frontier of European settlement in North America, or ecological. An ecotone is an ecological frontier. Some ecotones are very subtle and small-scale—there are dozens of tiny ecotones in any suburban yard—and others are very large-scale, like the border between steppe and forest running east-west across central Eurasia. Finally, a sharply defined border that limits movement in some way is a boundary; for example, the political borders of modern nations are boundaries. But nation-like political and linguistic boundaries were unknown in the Pontic-Caspian region between 4500 and 2500 BCE. The cultures we are interested in were tribal societies.1

Archaeologists’ interpretations of premodern tribal borders have changed in the last forty years. Most pre-state tribal borders are now thought to have been porous and dynamic—frontiers, not boundaries. More important, most are thought to have been ephemeral. The tribes Europeans encountered in their colonial ventures in Africa, South Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas were at first assumed to have existed for a long time. They often claimed antiquity for themselves. But many tribes are now believed to have been transient political communities of the historical moment. Like the Ojibwa, some might have crystallized only after contact with European agents who wanted to deal with bounded groups to facilitate the negotiation of territorial treaties. And the same critical attitude toward bounded tribal territories is applied to European history. Ancient European tribal identities—Celt, Scythian, Cimbri, Teuton, and Pict—are now frequently seen as convenient names for chameleon-like political alliances that had no true ethnic identity, or as brief ethnic phenomena that were unable to persist for any length of time, or even as entirely imaginary later inventions.2

Pre-state language borders are thought to have been equally fluid, characterized by intergrading local dialects rather than sharp boundaries. Where language and material culture styles (house type, town type, economy, dress, etc.) did coincide geographically to create a tribal ethnolinguistic frontier, we should expect it to have been short-lived. Language and material culture can change at different speeds for different reasons, and so are thought to grow apart easily. Historians and sociologists from Eric Hobsbawm to Anthony Giddens have proposed that there were no really distinct and stable ethnolinguistic borders in Europe until the late eighteenth century, when the French Revolution ushered in the era of nation-states. In this view of the past only the state is accorded both the need and the power to warp ethnolinguistic identity into a stable and persistent phenomenon, like the state itself. So how can we hope to identify ephemeral language frontiers in 3500 BCE? Did they even exist long enough to be visible archaeologically?3

Unfortunately this problem is compounded by the shortcomings of archaeological methods. Most archaeologists would agree that we do not really know how to recognize tribal ethnolinguistic frontiers, even if they were stable. Pottery styles were often assumed by pre—World War II archaeologists to be an indicator of social identity. But we now know that no simple connection exists between pottery types and ethnicity; as noted in chapter 1, every modern archaeology student knows that “pots are not people.” The same problem applies to other kinds of material culture. Arrow-point types did seem to correlate with language families among the San hunter-gatherers of South Africa; however, among the Contact-period Native Americans in the northeastern U.S., the “Madison”-type arrow point was used by both Iroquoian and Algonkian speakers—its distribution had no connection to language. Almost any object could have been used to signal linguistic identity, or not. Archaeologists have therefore rejected the possibility that language and material culture are correlated in any predictable or recognizable way.4

But it seems that language and material culture are related in at least two ways. One is that tribal languages are generally more numerous in any long-settled region than tribal material cultures. Silver and Miller noticed, in 1997, that most tribal regions had more languages than material cultures. The Washo and Shoshone in the Great Basin had very different languages, of distinct language families, but similar material cultures; the Pueblo Indians had more languages than material cultures; the California Indians had more languages than stylistic groups; and the Indians of the central Amazon are well known for their amazing linguistic variety and broadly similar material cultures. A Chicago Field Museum study of language and material culture in northern New Guineau, the most detailed of its type, confirmed that regions defined by material culture were crisscrossed with numerous materially invisible language borders.5 But the opposite pattern seems to be rare: a homogeneous tribal language is rarely separated into two very distinct bundles of material culture. This regularity seems discouraging, as it guarantees that many prehistoric language borders must be archaeologically invisible, but it does help to decide such questions as whether one language could have covered all the varied material culture groups of Copper Age Europe (probably not; see chapter 4).

The second regularity is more important: language is correlated with material culture at very long-lasting, distinct material-culture borders.

Persistent cultural frontiers have been ignored, because, I believe, they were dismissed on theoretical grounds.6 They are not supposed to be there, since pre-state tribal borders are interpreted today as ephemeral and unstable. But archaeologists have documented a number of remarkably long-lasting, prehistoric, material-culture frontiers in settings that must have been tribal. A robust, persistent frontier separated Iroquoian and Algonkian speakers along the Hudson Valley, who displayed different styles of smoking pipes, subtle variations in ceramics, quite divergent house and settlement types, diverse economies, and very different languages for at least three centuries prior to European contact. Similarly the Linear Pottery/Lengyel farmers created a robust material-culture frontier between themselves and the indigenous foragers in northern Neolithic Europe, a moving border that persisted for at least a thousand years; the Criş/Tripolye cultures were utterly different from the Dnieper-Donets culture on a moving frontier between the Dniester and Dnieper Rivers in Ukraine for twenty-five hundred years during the Neolithic and Eneolithic; and the Jastorf and Halstatt cultures maintained distinct identities for centuries on either side of the lower Rhine in the Iron Age.7 In each of these cases cultural norms changed; house designs, decorative aesthetics, and religious rituals were not frozen in a single form on either side. It was the persistent opposition of bundles of customs that defined the frontier rather than any one artifact type.

Persistent frontiers need not be stable geographically—they can move, as the Romano-Celt/Anglo-Saxon material-culture frontier moved across Britain between 400 and 700 CE, or the Linear Pottery/forager frontier moved across northern Europe between 5400 and 5000 BCE. Some material-culture frontiers, described in the next chapters, survived for millennia, in a pre-state social world governed just by tribal politics—no border guards, no national press. Particularly clear examples defined the edges of the Pontic-Caspian steppes on the west (Tripolye/Dnieper), on the north (Russian forest forager/steppe herder), and on the east (Volga-Ural steppe herder/Kazakh steppe forager). These were the borders of the region that probably was the homeland of Proto-Indo-European. If ancient ethnicities were ephemeral and the borders between them short-lived, how do we understand premodern tribal material-culture frontiers that persisted for thousands of years? And can language be connected to them?

I think the answer is yes. Language is strongly associated with persistent material-culture frontiers that are defined by bundles of opposed customs, what I will call robust frontiers.8 The migrations and frontier formation processes that followed the collapse of the Roman Empire in western Europe provide the best setting to examine this association, because documents and place-names establish the linguistic identity of the migrants, the locations of newly formed frontiers, and their persistence over many centuries in political contexts where centralized state governments were weak or nonexistent. For example, the cultural frontier between the Welsh (Celtic branch) and the English (Germanic branch) has persisted since the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Romano-Celtic Britain during the sixth century. Additional conquests by Norman-English feudal barons after 1277 pushed the frontier back to the landsker, a named and overtly recognized ethnolinguistic frontier between Celtic Welsh-speaking and Germanic English-speaking populations that persisted to the present day. They spoke different languages (Welsh/English), built different kinds of churches (Celtic/Norman English), managed agriculture differently and with different tools, used diverse systems of land measurement, employed dissimilar standards of justice, and maintained a wide variety of distinctions in dress, food, and custom. For many centuries men rarely married across this border, maintaining a genetic difference between modern Welsh and English men (but not women) in traits located on the male Y chromosome.

Other post-Roman ethnolinguistic frontiers followed the same pattern. After the fall of Rome German speakers moved into the northern cantons of Switzerland, and the Gallic kingdom of Burgundy occupied what had been Gallo-Roman western Switzerland. The frontier between them still separates ecologically similar regions within a single modern state that differ in language (German-French), religion (Protestant-Catholic), architecture, the size and organization of landholdings, and the nature of the agricultural economy. Another post-Roman migration created the Breton/French frontier across the base of the peninsula of Brittany, after Romano-Celts migrated to Brittany from western Britain around 400–600 CE, fleeing the Anglo-Saxons. For more than fifteen hundred years the Celtic-speaking Bretons have remained distinct from their French-speaking neighbors in rituals, dress, music, and cuisine. Finally, migrations around 900–1000 CE brought German speakers into what is now northeastern Italy, where the persistent frontier between Germans and Romance speakers inside Italy was studied by Eric Wolf and John Cole in the 1960s. Although in this case both cultures were Catholic Christians, after a thousand years they still maintained different languages, house types, settlement organizations, land tenure and inheritance systems, attitudes toward authority and cooperation, and quite unfavorable stereotypes of each other. In all these cases documents and inscriptions show that the ethnolinguistic oppositions were not recent or invented but deeply historical and persistent.9

These examples suggest that most persistent, robust material-culture frontiers were ethnolinguistic. Robust, persistent, material-culture frontiers are not found everywhere, so only exceptional language frontiers can be identified. But that, of course, is better than nothing.

Unlike the men of Wales and England, most people moved back and forth across persistent frontiers easily. A most interesting fact about stable ethnolinguistic frontiers is that they were not necessarily biological; they persisted for an extraordinarily long time despite people regularly moving across them. As Warren DeBoer described in his study of native pottery styles in the western Amazon basin, “ethnic boundaries in the Ucayali basin are highly permeable with respect to bodies, but almost inviolable with respect to style.”10 The back-and-forth movement of people is indeed the principal focus of most contemporary borderland studies. The persistence of the borders themselves has remained understudied, probably because modern nation-states insist that all borders are permanent and inviolable, and many nation-states, in an attempt to naturalize their borders, have tried to argue that they have persisted from ancient times. Anthropologists and historians alike dismiss this as a fiction; the borders I have discussed frequently persist within modern nation-states rather than corresponding to their modern boundaries. But I think we have failed to recognize that we have internalized the modern nation-state’s basic premise by insisting that ethnic borders must be inviolable boundaries or they did not really exist.

If people move across an ethno-linguistic frontier freely, then the frontier is often described in anthropology as, in some sense, a fiction. Is this just because it was not a boundary like that of a modern nation? Eric Wolf used this very argument to assert that the North American Iroquois did not exist as a distinct tribe during the Colonial period; he called them a multiethnic trading company. Why? Because their communities were full of captured and adopted non-Iroquois. But if biology is independent of language and culture, then the simple movement of Delaware and Nanticoke bodies into Iroquoian towns should not imply a dilution of Iroquoian culture. What matters is how the immigrants acted. Iroquoian adoptees were required to behave as Iroquois or they might be killed. The Iroquoian cultural identity remained distinct, and it was long established and persistent. The idea that European nation-states created the Iroquois “nation” in their own European image is particularly ironic in view of the fact that the five nations or tribes of the pre-European Northern Iroquois can be traced back archaeologically in their traditional five tribal territories to 1300 CE, more than 250 years before European contact. An Iroquois might argue that the borders of the original five nations of the Northern Iroquois were demonstrably older than those of many European nation-states at the end of the sixteenth century.11

Language frontiers in Europe are not generally strongly correlated with genetic frontiers; people mated across them. But persistent ethnolinguistic frontiers probably did originate in places where relatively few people moved between neighboring mating and migration networks. Dialect borders usually are correlated with borders between socioeconomic “functional zones,” as linguists call a region marked by a strong network of intra-migration and socioeconomic interdependence. (Cities usually are divided into several distinct socioeconomic-linguistic functional zones.) Labov, for example, showed that dialect borders in central Pennsylvania correlated with reduced cross-border traffic flow densities at the borders of functional zones. In some places, like the Welsh/English border, the cross-border flow of people was low enough to appear genetically as a contrast in gene pools, but at other persistent frontiers there was enough cross-border movement to blur genetic differences. What, then, maintained the frontier itself, the persistent sense of difference?12

Persistent, robust premodern ethnolinguistic frontiers seem to have survived for long periods under one or both of two conditions: at large-scale ecotones (forest/steppe, desert/savannah, mountain/river bottom, mountain/coast) and at places where long-distance migrants stopped migrating and formed a cultural frontier (England/Wales, Britanny/France, German Swiss/French Swiss). Persistent identity depended partly on the continuous confrontation with Others that was inherent in these kinds of borders, as Frederik Barth observed, but it also relied on a home culture behind the border, a font of imagined tradition that could continuously feed those contrasts, as Eric Wolf recognized in Italy.13 Let us briefly examine how these factors worked together to create and maintain persistent frontiers. We begin with borders created by long-distance migration.

During the 1970s and 1980s the very idea of folk migrations was avoided by Western archaeologists. Folk migrations seemed to represent the boiled-down essence of the discredited idea that ethnicity, language, and material culture were packaged into neatly bounded societies that careened across the landscape like self-contained billiard balls, in a famously dismissive simile. Internal causes of social change—shifts in production and the means of production, in climate, in economy, in access to wealth and prestige, in political structure, and in spiritual beliefs—all got a good long look by archaeologists during these decades. While archaeologists were ignoring migration, modern demographers became very good at picking apart the various causes, recruiting patterns, flow dynamics, and targets of modern migration streams. Migration models moved far beyond the billiard ball analogy. The acceptance of modern migration models in the archaeology of the U.S. Southwest and in Iroquoian archaeology in the Northeast during the 1990s added new texture to the interpretation of Anasazi/Pueblo and Iroquoian societies, but in most other parts of the world the archaeological database was simply not detailed enough to test the very specific behavioral predictions of modern migration theories.14 History, on the other hand, contains a very detailed record of the past, and among modern historians migration is accepted as a cause of persistent cultural frontiers.

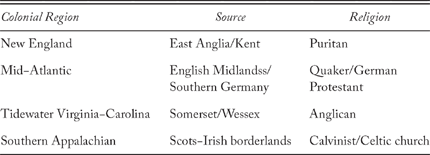

The colonization of North America by English speakers is one prominent example of a well-studied, historical connection between migration and ethnolinguistic frontier formation. Decades of historical research have shown, surprisingly, that while the borders separating Europeans and Native Americans were important, those that separated different British cultures were just as significant. Eastern North America was colonized by four distinct migration streams that originated in four different parts of the British Isles. When they touched down in eastern North America, they created four clearly bounded ethnolinguistic regions between about 1620 and 1750. The Yankee dialect was spoken in New England. The same region also had a distinctive form of domestic architecture—the salt-box clapboard house—as well as its own barn and church architecture, a distinctive town type (houses clustered around a common grazing green), a peculiar cuisine (often baked, like Boston baked beans), distinct fashions in clothing, a famous style of gravestones, and a fiercely legalistic approach to politics and power. The geographic boundaries of the New England folk-culture region, drawn by folklorists on the basis of these traits, and the Yankee dialect region, drawn by linguists, coincide almost exactly. The Yankee dialect was a variant of the dialect of East Anglia, the region from which most of the early Pilgrim migrants came; and New England folk culture was a simplified version of East Anglian folk culture. The other three regions also exhibited strongly correlated dialects and folk cultures, as defined by houses, barn types, fence types, the frequency of towns and their organization, food preferences, clothing styles, and religion. One was the mid-Atlantic region (Pennsylvania Quakers from the English Midlands), the third was the Virginia coast (Royalist Anglican tobacco planters from southern England, largely Somerset and Wessex), and the last was the interior Appalachians (borderlanders from the Scotch-Irish borders). Both dialect and folk culture are traceable in each case to a particular region in the British Isles from which the first effective European settlers came.15

The four ethnolinguistic regions of Colonial eastern North America were created by four separate migration streams that imported people with distinctive ethnolinguistic identities into four different regions where simplified versions of their original linguistic and material differences were established, elaborated, and persisted for centuries (table 6.1). In some ways, including modern presidential voting patterns, the remnants of these four regions survive even today. But can modern migration patterns be applied to the past, or do modern migrations have purely modern causes?

TABLE 6.1

Migration Streams to Colonial North America

Many archaeologists think that modern migrations are fueled principally by overpopulation and the peculiar boundaries of modern nation-states, neither of which affected the prehistoric world, making modern migration studies largely irrelevant to prehistoric societies.16 But migrations have many causes besides overpopulation within state borders. People do not migrate, even in today’s crowded world, simply because there are too many at home. Crowding would be called a “push” factor by modern demographers, a negative condition at home. But there are other kinds of “push” factors—war, disease, crop failure, climate change, institutionalized raiding for loot, high bride-prices, the laws of primogeniture, religious intolerance, banishment, humiliation, or simple annoyance with the neighbors. Many causes of today’s migrations and those in the past were social, not demographic. In ancient Rome, feudal Europe, and many parts of modern Africa, inheritance rules favored older siblings, condemning the younger ones to find their own lands or clients, a strong motive for them to migrate.17 Pushes could be even more subtle. The persistent outward migrations and conquests of the pre-Colonial East African Nuer were caused, according to Raymond Kelley, not by overpopulation within Nuerland but rather by a cultural system of bride-price regulations that made it very expensive for young Nuer men to obtain a socially desirable bride. A bride-price was a payment made by the groom to the bride’s family to compensate for the loss of her labor. Escalation in bride-prices encouraged Nuer men to raid their non-Nuer neighbors for cattle (and pastures to support them) that could be used to pay the elevated bride-price for a high-status marriage. Tribal status rivalries supported by high brideprices in an arid, low-productivity environment led to out-migration and the rapid territorial expansion of the Nuer.18 Grassland migrations among tribal pastoralists can be “pushed” by many things other than absolute resource shortages.

Regardless of how “pushes” are defined, no migration can be adequately explained by “pushes” alone. Every migration is affected as well by “pull” factors (the alleged attractions of the destination, regardless of whether they are true), by communication networks that bring information to potential migrants, and by transport costs. Changes in any of these factors will raise or lower the threshold at which migration becomes an attractive option. Migrants weigh these dynamics, for far from being an instinctive response to overcrowding, migration is often a conscious social strategy meant to improve the migrant’s position in competition for status and riches. If possible, migrants recruit clients and followers among the people at home, convincing them also to migrate, as Julius Caesar described the recruitment speeches of the chiefs of the Helvetii prior to their migration from Switzerland into Gaul. Recruitment in the homeland by potential and already departed migrants has been a continuous pattern in the expansion and reproduction of West African clans and lineages, as Igor Kopytoff noted. There is every reason to believe that similar social calculations have inspired migrations since humans evolved.

Large, sustained migrations, particularly those that moved a long distance from one cultural setting into a very different one, or folk migrations, can be identified archaeologically. Emile Haury knew most of what to look for already in his excavations in Arizona in the 1950s: (1) the sudden appearance of a new material culture that has no local antecedents or prototypes; (2) a simultaneous shift in skeletal types (biology); (3) a neighboring territory where the intrusive culture evolved earlier; and (4) (a sign not recognized by Haury) the introduction of new ways of making things, new technological styles, which we now know are more “fundamental” (like the core vocabulary in linguistics) than decorative styles.

Smaller-scale migrations by specialists, mercenaries, skilled craft workers, and so on, are more difficult to identify. This is partly because archaeologists have generally stopped with the four simple criteria just described and neglected to analyze the internal workings even of folk migrations. To really understand why and how folk migrations occurred, and to have any hope of identifying small-scale migrations, archaeologists have to study the internal structure of long-distance migration streams, both large and small. The organization of migrating groups depends on the identity and social connections of the scouts (who select the target destination); the social organization of information sharing (which determines who gets access to the scouts’ information); transportation technology (cheaper and more effective transport makes migration easier); the targeting of destinations (whether they are many or few); the identity of the first effective settlers (also called the “charter group”); return migration (most migrations have a counterflow going back home); and changes in the goals and identities of migrants who join the stream later. If we look for all these factors we can better understand why and how migrations happened. Sustained migrations, particularly by pioneers looking to settle in new homes, can create very long-lasting, persistent ethnolinguistic frontiers.

Access to the scouts’ information defines the pool of potential migrants. Studies have found that the first 10% of new migrants into a region is an accurate predictor of the social makeup of the population that will follow them. This restriction on information at the source produces two common behaviors: leapfrogging and chain migration. In leapfrogging, migrants go only to those places about which they have heard good things, skipping over other possible destinations, sometimes moving long distances in one leap. In chain migration, migrants follow kin and co-residents to familiar places with social support, not to the objectively “best” place. They jump to places where they can rely on people they know, from point to targeted point. Recruitment usually is relatively restricted, and this is clearly audible in their speech.

Colonist speech generally is more homogeneous than the language of the homeland they left behind. Dialectical differences were fewer among Colonial-era English speakers in North America than they were in the British Isles. The Spanish dialects of Colonial South America were more homogeneous than the dialects of Southern Spain, the home region of most of the original colonists. Linguistic simplification has three causes. One is chain migration, where colonists tend to recruit family and friends from the same places and social groups that the colonists came from. Simplification also is a normal linguistic outcome of mixing between dialects in a contact situation at the destination.19 Finally, simplification is encouraged among long-distance migrants by the social influence of the charter group.

The first group to establish a viable social system in a new place is called the charter group, or the first effective settlers.20 They generally get the best land. They might claim rights to perform the highest-status rituals, as among the Maya of Central America or the Pueblo Indians of the American Southwest. In some cases, for example, Puritan New England, their councils choose who is permitted to join them. Among Hispanic migrants in the U.S. Southwest, charter groups were called apex families because of their structural position in local prestige hierarchies. Many later migrants were indebted to or dependent on the charter group, whose dialect and material culture provided the cultural capital for a new group identity. Charter groups leave an inordinate cultural imprint on later generations, as the latter copy the charter group’s behavior, at least publicly. This explains why the English language, English house forms, and English settlement types were retained in nineteenth-century Ohio, although the overwhelming majority of later immigrants was German. The charter group, already established when the Germans arrived, was English. It also explains why East Anglian English traits, typical of the earliest Puritan immigrants, continued to typify New England dialectical speech and domestic architecture long after the majority of later immigrants arrived from other parts of England or Ireland. As a font of tradition and success in a new land, the charter group exercised a kind of historical cultural hegemony over later generations. Their genes, however, could easily be swamped by later migrants, which is why it is often futile to pursue a genetic fingerprint associated with a particular language.

The combination of chain migration, which restricted the pool of potential migrants at home, and the influence of the charter group, which encouraged conformity at the destination, produced a leveling of differences among many colonists. Simplification (fewer variants than in the home region) and leveling (the tendency toward a standardized form) affected both dialect and material culture. In material culture, domestic architecture and settlement organization—the external form and construction of the house and the layout of the settlement—particularly tended toward standardization, as these were the most visible signals of identity in any social landscape.21 Those who wished to declare their membership in the mainstream culture adopted its external domestic forms, whereas those who retained their old house and barn styles (as did some Germans in Ohio) became political, as well as architectural and linguistic, minorities. Linguistic and cultural homogeneity among long-distance migrants facilitated stereotyping by Others, and strengthened the illusion of shared interests and origins among the migrants.

Franz Boas, the father of American anthropology, found that the borders of American Indian tribes rarely correlated with geographic borders. Boas decided to study the diffusion of cultural ideas and customs across borders. But a certain amount of agreement between ecology and culture is not at all surprising, particularly among people who were farmers and animal herders, which Boas’s North American tribes generally were not. The length of the frost-free growing season, precipitation, soil fertility, and topography affect many aspects of daily life and custom among farmers: herding systems, crop cultivation, house types, the size and arrangement of settlements, favorite foods, sacred foods, the size of food surpluses, and the timing and richness of public feasts. At large-scale ecotones these basic differences in economic organization, diet, and social life can blossom into oppositional ethnic identities, which sometimes are complementary and mutually supportive, sometimes are hostile, and often are both. Frederick Barth, after working among the societies of Iran and Afghanistan, was among the first anthropologists to argue that ethnic identity was continuously created, even invented, at frontiers, rather than residing in the genes or being passively inherited from the ancestors. Oppositional politics crystallize who we are not, even if we are uncertain who we are, and therefore play a large role in the definition of ethnic identities. Ecotones were places where contrasting identities were likely to be reproduced and maintained for long periods because of structural differences in how politics and economics were played.22

Ecotones coincide with ethnolinguistic frontiers at many places. In France the Mediterranean provinces of the South and the Atlantic provinces of the North have been divided by an ethnolinguistic border for at least eight hundred years; the earliest written reference to it dates to 1284. The flat, tiled roofs of the South sheltered people who spoke the langue d’oc, whereas the steeply pitched roofs of the North were home to people who spoke the langue d’oil. They had different cropping systems, and different legal systems as well until they were forced to conform to a national legal standard. In Kenya the Nilotic-speaking pastoralist Maasai maintained a purely cattle-herding economy (or at least that was their ideal) in the dry plains and plateaus, whereas Bantu-speaking farmers occupied moister environments on the forested slopes of the mountains or in low wetlands. Probably the most famous anthropological example of this type was described by Sir Edmund Leach in his classic Political Systems of Highland Burma. The upland Kachin forest farmers, who lived in the hills of Burma (Myanmar), were distinct linguistically, and also in many aspects of ritual and material culture, from the Thai-speaking Shan paddy farmers who occupied the rich bottomlands in the river valleys. Some Kachin leaders adopted Shan identities on certain occasions, moving back and forth between the two systems. But the broader distinction between the two cultures, Kachin and Shan, persisted, a distinction rooted in different ecologies, for example, the contrasting reliability and predictability of crop surpluses, the resulting different potentials for surplus wealth, and the dissimilar social organizations required for upland forest and lowland paddy farming. Cultural frontiers rooted in ecological differences could survive for a long time, even with people regularly moving across them.23

Why do some language frontiers follow ecological borders? Does language just ride on the coattails of economy? Or is there an independent relationship between ecology and the way people speak? The linguists Daniel Nettle at Oxford University and Jane Hill at the University of Arizona proposed, in 1996 (independently, or at least without citing each other), that the geography of language reflects an underlying ecology of social relationships.24

Social ties require a lot of effort to establish and maintain, especially across long distances, and people are unlikely to expend all that energy unless they think they need to. People who are self-sufficient and fairly sure of their economic future tend to maintain strong social ties with a small number of people, usually people very much like themselves. Jane Hill calls this a localist strategy. Their own language, the one they grew up with, gets them everything they need, and so they tend to speak only that language—and often only one dialect of that language. (Most college-educated North Americans fit nicely in this category.) Secure people like this tend to live in places with productive natural ecologies or at least secure access to pockets of high productivity. Nettles showed that the average size of language groups in West Africa is inversely correlated with agricultural productivity: the richer and more productive the farmland, the smaller the language territory. This is one reason why a single pan-European Proto-Indo-European language during the Neolithic is so improbable.

But people who are moderately uncertain of their economic future, who live in less-productive territories and have to rely on multiple sources of income (like the Kachin in Burma or most middle-class families with two income earners), maintain numerous weak ties with a wider variety of people. They often learn two or more languages or dialects, because they need a wider network to feel secure. They pick up new linguistic habits very rapidly; they are innovators. In Jane Hill’s study of the Papago Indians in Arizona, she found that communities living in rich, productive environments adopted a “localist” strategy in both their language and social relations. They spoke just one homogeneous, small-territory Papago dialect. But communities living in more arid environments knew many different dialects, and combined them in a variety of nonstandard ways. They adopted a “distributed” strategy, one that distributed alliances of various kinds, linguistic and economic, across a varied social and ecological terrain. She proposed that arid, uncertain environments were natural “spread zones,” where new languages and dialects would spread quickly between communities that relied on diverse social ties and readily picked up new dialects from an assortment of people. The Eurasian steppes had earlier been described by the linguist Johanna Nichols as the prototypical linguistic spread zone; Hill explained why. Thus the association between language and ecological frontiers is not a case of language passively following culture; instead, there are independent socio-linguistic reasons why language frontiers tend to break along ecological frontiers.25

Language frontiers did not universally coincide with ecological frontiers or natural geographic barriers, even in the tribal world, because migration and all the other forms of language expansion prevented that. But the heterogeneity of languages—the number of languages per 1,000 km2— certainly was affected by ecology. Where an ecological frontier separated a predictable and productive environment from one that was unpredictable and unproductive, societies could not be organized the same way on both sides. Localized languages and small language territories were found among settled farmers in ecologically productive territories. More variable languages, fuzzier dialect boundaries, and larger language territories appeared among mobile hunter-gatherers and pastoralists occupying territories where farming was difficult or impossible. In the Eurasian steppes the ecological frontier between the steppe (unproductive, unpredictable, occupied principally by hunters or herders) and the neighboring agricultural lands (extremely productive and reliable, occupied by rich farmers) was a linguistic frontier through recorded history. Its persistence was one of the guiding factors in the history of China at one end of the steppes and of eastern Europe at the other.26

Persistent ecological and migration-related frontiers surrounded the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the Pontic-Caspian steppes. But the spread of the Indo-European languages beyond that homeland probably did not happen principally through chain-type folk migrations. A folk movement is not required to establish a new language in a strange land. Language change flows in the direction of accents that are admired and emulated by large numbers of people. Ritual and political elites often introduce and popularize new ways of speaking. Small elite groups can encourage widespread language shift toward their language, even in tribal contexts, in places where they succeed at introducing a new religion or political ideology or both while taking control of key territories and trade commodities. An ethnohistorical study of such a case in Africa among the Acholi illustrates how the introduction of a new ideology and control over trade can result in language spread even where the initial migrants were few in number.27

The Acholi are an ethnolinguistic group in northern Uganda and southern Sudan. They speak Luo, a Western Nilotic language. In about 1675, when Luo-speaking chiefs first migrated into northern Uganda from the south, the overwhelming majority of people living in the area spoke Central Sudanic or Eastern Nilotic languages—Luo was very much a minority language. But the Luo chiefs imported symbols and regalia of royalty (drums, stools) that they had adopted from Bantu kingdoms to the south. They also imported a new ideology of chiefly religious power, accompanied by demands for tribute service. Between about 1675 and 1725 thirteen new chiefdoms were formed, none larger than five villages. In these islands of chiefly authority the Luo-speaking chiefs recruited clients from among the lineage elders of the egalitarian local populations, offering them positions of prestige in the new hierarchy. Their numbers grew through marriage alliances with the locals, displays of wealth and generosity, assistance for local families in difficulty, threats of violence, and, most important, control over the inter-regional trade in iron prestige objects used to pay bride-prices. The Luo language spread slowly through recruitment.28 Then an external stress, a severe drought beginning in 1790–1800, affected the region. One ecologically favored Lou chiefdom—an old one, founded by one of the first Luo charter groups—rose to paramount status as its wealth was maintained through the crisis. The Luo language then spread rapidly. When European traders arrived from Egypt in the 1850s they designated the local people by the name of this widely spoken language, which they called Shooli, which became Achooli. The paramount chiefs acquired so much wealth through trade with the Europeans that they quickly became an aristocracy. By 1872 the British recorded a single Luo-speaking tribe called the Acholi, an inter-regional ethnic identity that had not existed two hundred years earlier.

Indo-European languages probably spread in a similar way among the tribal societies of prehistoric Europe. Out-migrating Indo-European chiefs probably carried with them an ideology of political clientage like that of the Acholi chiefs, becoming patrons of their new clients among the local population; and they introduced a new ritual system in which they, in imitation of the gods, provided the animals for public sacrifices and feasts, and were in turn rewarded with the recitation of praise poetry—all solidly reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European culture, and all effective public recruiting activities. Later Proto-Indo-European migrations also introduced a new, mobile kind of pastoral economy made possible by the combination of ox-drawn wagons and horseback riding. Expansion beyond a few islands of authority might have waited until the new chiefdoms successfully responded to external stresses, climatic or political. Then the original chiefly core became the foundation for the development of a new regional ethnic identity. Renfrew has called this mode of language shift elite dominance but elite recruitment is probably a better term. The Normans conquered England and the Celtic Galatians conquered central Anatolia, but both failed to establish their languages among the local populations they dominated. Immigrant elite languages are adopted only where an elite status system is not only dominant but is also open to recruitment and alliance. For people to change to a new language, the shift must provide a key to integration within the new system, and those who join the system must see an opportunity to rise within it.29

A good example of how an open social system can encourage recruitment and language shift, cited long ago by Mallory, was described by Frederik Barth in eastern Afghanistan. Among the Pathans (today usually called Pashtun) on the Kandahar plateau, status depended on agricultural surpluses that came from circumscribed river-bottom fields. Pathan landowners competed for power in local councils (jirga) where no man admitted to being subservient and all appeals were phrased as requests among equals. The Baluch, a neighboring ethnic group, lived in the arid mountains and were, of necessity, pastoral herders. Although poor, the Baluch had an openly hierarchical political system, unlike the Pathan. The Pathan had more weapons than the Baluch, more people, more wealth, and generally more power and status. Yet, at the Baluch-Pathan frontier, many dispossessed Pathans crossed over to a new life as clients of Baluchi chiefs. Because Pathan status was tied to land ownership, Pathans who had lost their land in feuds were doomed to menial and peripheral lives. But Baluchi status was linked to herds, which could grow rapidly if the herder was lucky; and to political alliances, not to land. All Baluchi chiefs were the clients of more powerful chiefs, up to the office of sardar, the highest Baluchi authority, who himself owed allegiance to the khan of Kalat. Among the Baluch there was no shame in being the client of a powerful chief, and the possibilities for rapid economic and political improvement were great. So, in a situation of chronic low-level warfare at the Pathan-Baluch frontier, former agricultural refugees tended to flow toward the pastoral Baluch, and the Baluchi language thus gained new speakers. Chronic tribal warfare might generally favor pastoral over sedentary economies as herds can be defended by moving them, whereas agricultural fields are an immobile target.

Folk migrations by pioneer farmers brought the first herding-and-farming economies to the edge of the Pontic-Caspian steppes about 5800 BCE. In the forest-steppe ecological zone northwest of the Black Sea the incoming pioneer farmers established a cultural frontier between themselves and the native foragers. This frontier was robust, defined by bundles of cultural and economic differences, and it persisted for about twenty-five hundred years. If I am right about persistent frontiers and language, it was a linguistic frontier; if the other arguments in the preceding chapters are correct, the incoming pioneers spoke a non—Indo-European language, and the foragers spoke a Pre-Proto-Indo-European language. Selected aspects of the new farming economy (a little cattle herding, a little grain cultivation) were adopted by the foragers who lived on the frontier, but away from the frontier the local foragers kept hunting and fishing for many centuries. At the frontier both societies could reach back to very different sources of tradition in the lower Danube valley or in the steppes, providing a continuously renewed source of contrast and opposition.

Eventually, around 5200–5000 BCE, the new herding economy was adopted by a few key forager groups on the Dnieper River, and it then diffused very rapidly across most of the Pontic-Caspian steppes as far east as the Volga and Ural rivers. This was a revolutionary event that transformed not just the economy but also the rituals and politics of steppe societies. A new set of dialects and languages probably spread across the Pontic-Caspian steppes with the new economic and ritual-political system. These dialects were the ancestors of Proto-Indo-European.

With a clearer idea of how language and material culture are connected, and with specific models indicating how migrations work and how they might be connected with language shifts, we can now begin to examine the archaeology of Indo-European origins.