5

Theological Foundations: The Importance of Place and the Need to Belong

It is rootlessness and not meaninglessness that characterizes the current crisis. There can be no meanings apart from roots.

Walter Brueggemann, Old Testament scholar and theologian[1]

Arif is a Rohingya, who is now a refugee in Bangladesh.[2] He cannot recall when his family moved from their native Bangladesh to Burma. All he remembers is that his father and grandfather had always been in Burma, and he grew up in a small village in northwest Burma. It had always been home for him. Though he is a Muslim, he never thought of himself as anything but Burmese. His family lived in the village, and he had a small plot of land which he farmed. His family had some cows and bulls, and a herd of goats. What Arif and hundreds of thousands of Rohingya in Burma do not have, however, is nationality. They are stateless.

Some years ago Arif was recruited into the Burmese army. Instead of being a soldier, he was made to work carrying supplies through the jungle, often without food and water and in slave like conditions. Because his children were still small at the time, his family was unable to cope with their small farm. Without an adult male in the house, people started stealing their cattle, and the fields began to be neglected. The hardest part was when people in the village and the neighbouring town would shout abuses at them and tell them to get out since they were foreigners and not “real” Burmese.

Finally, Arif deserted from the army, gathered his family, and fled to Bangladesh. They walked for three days through the jungle until they reached a refugee camp in Bangladesh. That was fifteen years ago. Life in the camp is hard as the family can not find much work to do. One day, their teenage daughter was raped, and the authorities did nothing to find the perpetrator.

Being ethnically Rohingya, Arif and his family were denied Burmese citizenship. As refugees in Bangladesh, they are not entitled to Bangladeshi citizenship. They have no home and nowhere to go as they don’t have any travel documents.

Because of recent publicity of the plight of the Rohingya refugees, one of the UN agencies is working to try to resettle them in a third country. After all these years, Arif and his family hope they can rebuild their lives in another country. But they still dream of their home and little farm in Burma and wonder if they will ever be able to go back, because that was home for them.

The biblical narrative is rich with insights about people on the move. It tells the stories of individuals and entire nations who either flee from evil, are sent into exile, wander lost, or migrate to seek a better life. When they finally find a home and are settled in a place, they experience the peace and security of belonging.

Too often church ministries to refugees, migrants, and the stateless focus exclusively on addressing physical needs and cultural orientation – including housing, jobs, access to health care, food, schooling for children, language classes, and learning about the local culture. These are all critical for survival and should be part of a first response. But after these needs are met, many refugees and migrants still feel lost and unloved, as if they do not belong. This feeling is not due to ingratitude or a sense of entitlement for more. What displaced people need more than anything else is community and a place to belong. A refugee being helped by a church in Vienna, Austria, said, “When I left my home country, I lost all my friends and family. And now in this church, I have discovered a new family.”

Walter Brueggemann explains that physical places have meaning in the biblical narrative. He writes, “Land is never simply physical dirt but is always physical dirt freighted with social meanings derived from historical experience.”[3] Physical land in a specific place with all the familiar sights, sounds, smells, and memories is where people have their sense of belonging. It is this specific land which gives them life as they grow their own food or earn their living, where they raise their family and make their home, and where they set up places to worship and encounter spiritual reality. Brueggemann looks at the Old Testament narrative through the lens of land and suggests that the central problem in the Bible is about homelessness (anomie).[4] The New Testament affirms this narrative in the letter to the Hebrews which refers to certain Old Testament characters as “being strangers and exiles” and “seeking a homeland” (Heb 11:13–14 ESV). God responds to the problem of displacement and lack of home by bringing them into an eternal city, a new home, and a new identity in a heavenly country (v. 16), a kingdom which will last into eternity.

The apostle Peter uses this imagery when he urges the followers of Christ, “as foreigners and exiles, to abstain from sinful desires, which wage war against your soul” (1 Pet 2:11). As citizens of a new kingdom, we are no longer to dwell on what has been familiar to us – the sinful desires and passions that are in conflict with the values of God – but become strangers and exiles to the lifestyle we once knew. Hebrews 12:1–2 encourages Christians to follow the example of Jesus who bore the loss of everything so that he could be “home” at the right hand of the Father. The apostle Paul writing to the church in Philippi states, “Our citizenship is in heaven” (Phil 3:20).

While much has been written on why God cares for the poor,[5] there is very little on why God cares for the displaced and the vulnerable foreigner (other than the fact that he simply does). God’s concern for the displaced (the refugee, the stateless, and the migrant) proceeds from the simple truth that all people are created to belong to specific places, to have a home, and to belong. The apostle Paul in Athens said, “From one man [God] made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands” (Acts 17:26). While Paul talks about groups of people (the nations), the principle of belonging to a specific place at a specific time is just as valid for individuals. This theological dimension of the interaction between place and human beings needs to be understood. Philosopher and Christian mystic Simone Weil explains,

To be rooted is perhaps the most important need of the human soul. It is the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active, and natural participation in the life of the community, which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations of the future. . . . It is necessary for him to draw well-nigh the whole of his moral, intellectual, and spiritual life by way of the environment of which he form[s] a natural part.[6]

The Bible consistently affirms that having social and psychological roots in this world is a significant human need and that God is concerned that people experience rootedness. This biblical concept and its implications on displacement are revealed within a theology of place.

Displacement and a Theology of Place

The biblical narrative of being displaced and then finding a home is still being played out today. What the displaced need more than anything else are people and a place; an embracing community that fosters belonging and a place that provides security. These are by no means unique needs only for those suffering displacement but rather basic human needs of all people. The Bible throughout shows that one of a person’s greatest needs is to belong to a place. The tragedy of displacement is that it denies a sense of place in this world.

Place is a central aspect of the human experience. Where we are is directly tied to who we are and impacts the dynamics of our relationships at all levels. New Testament scholar Gary Burge writes, “Each of us wants a place that we can call home, a place we may think of as our own, where familiar things are available, where old stories may be retold, where we experience connection with a legacy that stretches out behind us.”[7] South African theologian Craig Bartholomew calls this human need for place implacement, the idea that existence itself is tied to having a place.[8] He writes that God “intends for humans to be at home, to indwell, in their places; place and implacement is a gift and provides the possibility for imagining God in his creation.”[9] Belonging to a place gives a person an identity. In many cultures, a person’s full name will include either the name of their ancestral home or the town or village in which their family has roots.[10] The crisis of displacement matters to God precisely because belonging to a place is important to people.

The plight of many displaced is more than a problem of emotions but also a matter of law since they possess no official claim to rightfully be where they are. Achieving legal status in the places they reside can be elusive and leave individuals in precarious states of legal limbo. This problem is often compounded by the persisting trauma of having been uprooted in violent ways, often fleeing horrors and confronting threats to their lives. Stateless individuals who are denied citizenship anywhere in this world constantly feel like outsiders wherever they are, like unwanted occupiers of another’s turf. Displacement is also particularly devastating for children. Their emotional, social, and spiritual growth is deeply affected by the instability they pass through, and the wounds may require a lifetime to heal. Jenny McGill writes about the impact of being displaced and dislocated.

The migratory experience away from what is familiar brings a valuable sense of disjointedness. This feeling of dislocation positions one to recognize one’s humanness and reminds the sojourner how easily one can become helpless. Without one’s usual social and physical support, one is jolted from what is normally taken as a given, and the process of migration affords an opportunity to experience change and loss. Far from glamorizing the migrant’s journey, these losses can be excruciatingly painful and life-threatening.[11]

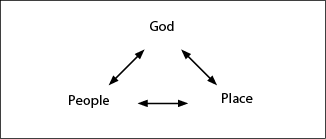

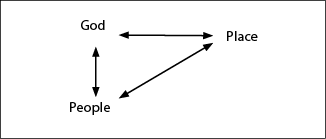

Anglican theologian John Inge argues that the Bible consistently demonstrates two theological principles concerning place: “first, that place is a fundamental category of human experience, and that, second, there is a threefold relationship between God, his people, and place.”[12]

Inge states that a general problem with modernity is the “notion that place is not integral to our experience of God or the world, but simply exists alongside us as an added extra.”

Unfortunately, this distortion of the God, people, and land relational dynamic impedes our understanding of and our responses to the needs of refugees, migrants, and the stateless. Failing to recognize the spiritual impact that occurs when place is lost limits the ability to meaningfully minister to refugees. The displaced have suffered more than simply the loss of home, lifestyle, and community; they have lost an important component to knowing and relating to God.

It is important to clarify that the issue at hand is not space, since all displaced people can make some claim to a degree of space. Rather the problem is about place. Brueggemann writes, “Land is never simply physical dirt but is always physical dirt freighted with social meanings derived from historical experience.”[14] The displaced are therefore separated from their places of “historical meaning.” Instead of meaningful places, they have been subjected to spaces that are uncomfortable and often oppressive. While the image of the “suffering migrant” is not always accurate – migrants, refugees, and stateless persons do achieve relatively stable situations of protection and opportunity – many others find themselves in refugee camps, urban slums, or detention facilities where life becomes an ongoing fight for survival with little sense of belonging.

Brueggemann calls the sense of not belonging, “rootlessness.” He writes, “It is rootlessness and not meaninglessness that characterizes the current crises. There are no meanings apart from roots.”[15] While he describes rootlessness as a problem of modern society, it is especially descriptive of the reality of refugees, migrants, and the stateless. The tragedy of displacement is not that it denies space but that it denies place where roots can be established and deepened, and where life-giving identities can be formed. Facing the legal and physical perils of displacement can lead the displaced to ultimately feel as if they do not have a place in this world altogether.

Place as both a literal and symbolic concept permeates the Bible. The opening drama of Genesis presents a theology of place “in the context of a complex, dynamic understanding of creation as ordered by God,” where humanity is placed within, not above, the fabric of creation.[16] All things – plants, creatures, and most of all humans – were created to fit within a dynamic arrangement so as to foster and increase life. Our world – with all of its physical, social, and cultural dimensions – is the context within which God choses to bless human beings.

Yet it is easy to see that the current state of the world is not the way it was designed to be. Sin has devastated the entirety of the created world, not just human beings. In the Genesis account, God’s judgment of sin results in displacement of human beings from Eden, banishment from their home and all that was familiar. Ever since then “the challenge of implacement and the danger of displacement are a constant part of the human condition.”[17] The deep human need for belonging to a place and the impact of displacement directly leads to a crisis where individuals suffer the loss of identity and a diminished sense of self, all in addition to the threats against their physical well-being. Displacement dehumanizes its victims, yet our modern world often fails to recognize this. Brueggemann states that existentialists do not understand that there is a “human hunger for a sense of place.”[18] Unfortunately, many of those who are responding to the displaced do not appreciate this fundamental human need.

The lives of refugees and the stateless are dominated by their loss of home and their quest to achieve secure lives for themselves and their families. This quest is complicated by the challenges of accessing legal status within our global community of nation-states. The trauma of losing what is valuable to them (such as a home community, loved ones and friends, sentimental possessions, and dreams for the future) is compounded by the lack of legal protections and access to human rights. This situation leaves the displaced rootless within the political systems of our modern world. They have become a type of sojourner, a term that Brueggemann explains must be understood beyond the technical definition of “resident alien”:

[Sojourner] means to be in a place, perhaps for an extended time, to live there and take some roots, but always to be an outsider, never belonging, always without right, title, or voice in decisions that matter. Such a one is on turf but without title to the turf, having nothing sure but trusting in words spoken that will lead to a place.[19]

Today’s “displaced sojourners” face exclusion, restrictions, and mistrust while trying to forge new lives, or while simply trying to survive. Political theorist Hannah Arendt writes vividly about the massive displacement she personally experienced in Europe during the aftermath of World War II. Her observation rings eerily true to the phenomenon unfolding today: “Once they had left their homeland they remained homeless; once they had left their state they became stateless; once they had been deprived of their human rights they were rightless, the scum of the earth.”[20] All too often the current rhetoric is that the displaced are scum to be avoided rather than human beings to be protected.

Interestingly, a theology of place helps explain why there are not more displaced individuals in the world. While millions have left their homes fleeing dangers and seeking the chance for life in new spaces, many millions choose not to leave. They willingly endure hardships and threats to their very lives by remaining in lands ravaged by war, poverty, human rights abuses, and insecurity. They do so because they intuitively know that life apart from their homes, places of history, and traditions and memories is not much of a life. It is not uncommon to hear, “Better to die in my own land than live in someone else’s.”

Amr al-Jabali lives in the Ashar neighbourhood of rebel-controlled East Aleppo. The 54-year-old is a painter and builder, and while there is plenty here which needs rebuilding and decoration, he doesn’t get much paid work these days.

He does, however, brave the bombs, the price hikes, and the electricity cuts of daily life in this part of the city, described by the UN as a “humanitarian catastrophe.”

But al-Jabali won’t leave. “I’ve never left Aleppo in my life, and by the grace of God I won’t ever leave,” he told The New Arab.

As many as 275,000 people remain in East Aleppo. They stay out of attachment to their homes, an inability to leave safely, for political reasons and others. These are the stories of a few of those who refuse to leave.

Al-Jabali is simply too attached to Aleppo, and has lived here since he was born more than a half century ago. Despite the current hardships, he even has hope for the future.[21]

Conclusion: Citizens of a Kingdom Above All Things

Despite historic levels of effort and resources being poured into aid and humanitarian relief, the present crises of refugees, migration, and statelessness continue to swell. Is there hope for those to whom displacement is an inescapable reality? The Bible answers with a triumphant, “Yes!” God is indeed concerned with “rootage” in our current world of political entities.

Various human rights’ conventions state that everyone should have a nationality and live securely in a nation-state. The displaced should be given every opportunity to not just find a space where they can rebuild their lives, but be encouraged to discover and create a place they can call home, create history, and find meaning. The humanitarian community needs to understand this and see it as the goal, whether it is achieved by refugee resettlement in a third country, by returning refugees to their home countries, or even while remaining stranded in their first country of refuge.

God, knowing the fragility of human existence and the corruption of social and political systems, moves beyond the physical, political, and social. His ultimate concern is for human placement within his eternal kingdom, a security that will last for eternity. In the Old Testament, God’s desire for his chosen people was to provide a preview of his kingdom to prepare the world for when it finally arrives in all its fullness. Prophetic Scripture paints a picture of a coming place where sorrows cease, pain is no more, and injustice is eliminated.[22] Jesus built on this tradition by proclaiming the arrival of God’s kingdom, and what a peculiar kingdom it is. Rather than establishing a realm, he declared that the reign of God is not limited to any physical parameters. The Gospels present a world where “sacred space is no longer defined simply in terms [that are physical] . . . but wherever Jesus is present with his followers.”[23]

The New Testament refers to certain Old Testament characters as “being strangers and exiles” who were “seeking a homeland” (Heb 11:13–14 ESV). It points to a new understanding of identity that is no longer tied to a specific physical location. “No longer is a geographical place a destination of religious faithfulness,”[24] nor can any form of earthly status grant a heavenly identity.

The displaced understand Brueggemann’s statement that “our lives are set between expulsion and anticipation, of losing and expecting, of being uprooted and re-rooted, of being dislocated because of impertinence and being relocated in trust.”[25] In many ways they epitomize the struggle of existing “between” as they suffer the most severe of our modern world’s flux and threats. Yet the Bible objects to any conclusion that the tragedy of displacement be the end of anyone’s story. The enduring message of Scripture is clear: True human placement cannot be found in any physical place in the world, but rather in God who calls us out into a new consciousness.[26] The ultimate hope for the displaced, and for all of us, is that “the anticipation, the promise, is of landedness, a place which is rooted in the word of God.”[27]

The revelation of the kingdom of God causes us to rethink the very status of the displaced. By positioning the true meaning of place and belonging within the person of Christ and his kingdom rather than in any physical place, Scripture suggests that the displaced actually occupy a spiritually privileged position within the arrangement of God’s kingdom. Lebanese scholar Martin Accad argues such a dynamic in his reading of 1 Peter 2:9–10: “But you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s special possession, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light. Once you were not a people, but now you are the people of God; once you had not received mercy, but now you have mercy.” He writes, “In the Bible’s perspective, it is the stateless first, the non-citizens, the refugees and immigrants – before those of us who are complacently ‘stateful.’”[28] Drawing the displaced into firm placement within himself is indeed at the very heart of what God has done and is doing throughout his work of salvation in this world.

McGill writes that God uses migration, even forced displacement, to reshape human identity.[29] The intent of God is therefore a type of dual citizenship where people are securely established citizens of this world (with all the status, rights, and privileges it exhibits) and citizens of God’s kingdom. In this dual identity an earthly sense of belonging to a particular place and a heavenly citizenship to an eternal homeland are intertwined. Unless people are able to understand and experience what it means to physically, socially, and psychologically belong here on earth, they will have a hard time understanding what it means to belong in a heavenly kingdom. At the same time, as painful and heart-wrenching as the experience of losing everything and being displaced is, the good news is that the loss of an earthly home by no means disqualifies the refugee, the migrant, and the stateless from receiving a heavenly and everlasting citizenship, if they choose to accept the gift God offers. We should not be surprised to discover that in their desperate hunger for a home, God is bringing the displaced, those rejected by this world, into his kingdom. McGill writes, “In using migration . . . God seems to teach God’s people that dwelling is more about an identity of being than a location.”[30]

While the narrative of displacement is often (rightfully) a narrative of pain, struggle, and misery, those who truly engage the lives of the displaced are often inspired by what they witness. In the midst of unthinkable hardships and loss, many millions are protesting against defeat and clinging to hope for the future. Rather than giving up on life, they continue with life. They grow from adolescence to adulthood, fall in love, get married, raise families, carry on traditions, seek to forge livelihoods, and wait for the time when their fortunes will change and their human rights and dignity will be restored. Many who have engaged compassionately with the displaced find the experience transformative; they are inspired by examples of individual faith that testify to God’s nourishing presence in the wilderness and hope that a promised land is to come. If viewed with spiritual eyes, one will see among the “strangers in the kingdom” countless declarations of what Inge identifies as one of Scripture’s enduring messages of hope for all people:

The ultimate importance of the material that the Christian faith declares, is something to which sacramental encounters in the church and the world point. They point towards our ultimate destiny which is to be implaced, where the nature of the places in which we will find ourselves will be a transfigured version of the places here and now.[31]

McGill in her research with migrants found that they were in “a heightened position to search for God and seek his help. The challenges of migration offer them the precarious opportunity to rely on God through dependence on others. This means the placing of trust in fellow humans while placing ultimate dependence on God.”[32] While migration and displacement are destructive to individuals and families, God uses these situations to draw people into a deeper relationship with him. Joseph the patriarch, reflecting on his forced migration from his family and home and being trafficked into the humiliation and degradation of slavery, in retrospect could say with confidence to his oppressors, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good” (Gen 50:20).

Questions for Reflection and Discussion

1. When you think about your home, what is it about that place that gives you a sense of home? How would you feel if you were away from it – or how did you feel when your home was taken from you?

2. The issue of identity is complex. What are the different dimensions of your identity? How do you describe/identify who you are?

3. Displaced individuals have lost or been denied so much. What are some ways you can help them create a new home and become part of a community?

4. While respecting their faith (which may be different than yours), what are some ways you can reveal what the kingdom of God is like and share with them the God you worship?