Selections from the Final Report of the Ad Hoc Tuskegee Syphilis Study Panel, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1973

April 28, 1973

Dr. Charles C. Edwards

Assistant Secretary for Health

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

Washington, D.C. 20202

Dear Doctor Edwards:

The final report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel is transmitted herewith. The Chairman specifically abstains from concurrence in this final report but recognizes his responsibility to submit it.

Sincerely yours,

Broadus N. Butler, Ph.D.

President

Dillard University

Charter

Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs

Purpose

The Ad Hoc Advisory Panel was convened by the U.S. Secretary for Health, Education and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services) to investigate the circumstances surrounding the study.

Originally published as Final Report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service, 1973), 1–3, 6–15, 23–24, 47.

To fulfill the public pledge of the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs to investigate the circumstances surrounding the Tuskegee, Alabama, study of untreated syphilis in the male Negro initiated by the United States Public Health Service in 1932.

Authority

The committee is established under the provisions of Section 222 of the Public Health Service Act, as amended, 42 US Code 217a, and in accordance with the provisions of Executive Order 11671, which sets forth standards for the formation and use of advisory committees.

Function

The committee will advise the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs on the following specific aspects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study:

Determine whether the study was justified in 1932 and whether it should have been continued when penicillin became generally available.

Recommend whether the study should be continued at this point in time, and if not, how it should be terminated in a way consistent with the rights and health needs of its remaining participants.

Determine whether existing policies to protect the rights of patients participating in health research conducted or supported by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare are adequate and effective and to recommend improvements in these policies, if needed.

Structure

The committee will consist of nine members, including the Chairman, not otherwise in the full-time employ of the Federal Government. Members will be selected by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs from citizens representing medicine, law, religion, labor, education, health administration, and public affairs.

The Panel members will be invited to serve for a period not to extend beyond December 31, 1972, unless an extension beyond that time is approved by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs. The Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific affairs will designate the Chairman.

Management and staff services will be provided by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs.

Meetings

Meetings will be held at the call of the Chairman, with the advance approval of a Government official who shall also approve the agenda. A Government official will be present at all meetings.

Meetings shall be conducted, and records of the proceedings kept as required by Executive Order 11671 and applicable Departmental regulations.

Compensation

Members who are not full-time Federal employees will be paid at the rate of $100 per day for time spent at meetings, plus per diem and travel expenses in accordance with Standard Government Travel Regulations.

Annual Cost Estimate

Estimated annual cost for operating the committee, including compensation and travel expenses of members but excluding staff support, is $74,000. Estimate of annual man years of staff support required is one year at an estimated annual cost of $16,000.

Report

A final report based on the committee’s investigation will be made to the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs. A copy of this report shall be provided to the Department Committee Management Officer.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs will terminate on December 31, 1972, unless extension beyond that date is requested an approved.

FORMAL DETERMINATION

By authority delegated to me by the Secretary on September 29, 1969, I hereby determine that the formation of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs is in the public interest in connection with the performance of duties imposed on the Department by law, and that such duties can best be performed through the advice and counsel of such a group.

8/28/72(sgd.) Merlin K. DuVal, M.D.

Date Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs

Charter

Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health

Purpose

To fulfill the public pledge of the Assistant Secretary for Health to investigate the circumstances surrounding the Tuskegee, Alabama, study of untreated syphilis in the male Negro initiated by the United States Public Health Service in 1932.

Authority

The committee is established under the provisions of Section 222 of the Public Health Service Act, as amended, 42 US Code 217a; the Panel is governed by provisions of Executive Order 11671, which sets forth standards for the formation and use of advisory committees.

Function

The committee will advise the Assistant Secretary for Health on the following specific aspects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study:

Determine whether the study was justified in 1932 and whether it should have been continued when penicillin became generally available.

Recommend whether the study should be continued at this point in time, and if not, how it should be terminated in a way consistent with the rights and health needs of its remaining participants.

Determine whether existing policies to protect the rights of patients participating in health research conducted or supported by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare are adequate and effective and to recommend improvements in these policies, if needed.

Structure

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health consists of nine members, including the Chairman, not otherwise in the full-time employ of the Federal Government. Members are selected by the Assistant Secretary for Health from citizens representing medicine, law, religion, labor, education, health administration, and public affairs. The Chairman is designated by the Assistant Secretary for Health.

The Panel members are invited to serve for a period not to extend beyond March 31, 1973, unless an extension beyond that time is approved by the Assistant Secretary for Health.

Management and staff services will be provided by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health which supplies the Executive Secretary.

Meetings

Meetings will be held at the call of the Chairman, with the advance approval of a Government official who shall also approve the agenda. A Government official will be present at all meetings.

Meetings are open to the public except as determined otherwise by the Secretary; notice of all meetings is given to the public.

Meetings shall be conducted, and records of the proceedings kept, as required by applicable laws and Departmental regulations.

Compensation

Members who are not full-time Federal employees will be paid at the rate of $100 per day for time spent at meetings, plus per diem and travel expenses in accordance with Standard Government Travel Regulations.

Annual Cost Estimate

Estimated annual cost for operating the Panel, including compensation and travel expenses of members but excluding staff support, is $74,000. Estimate of annual man years of staff support required is one year, at an estimated annual cost of $16,000.

Report

A final report based on the Panel’s investigation will be made to the Assistant Secretary for Health, not later than April 30, 1973, which contains as a minimum a list of members and their business addresses, the dates and places of meetings, and a summary of the Panel’s activities and recommendations. A copy of this report shall be provided to the Department Committee Management Officer.

Termination Date

Unless renewed by appropriate action prior to its expiration, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel to the Assistant Secretary for Health will terminate on March 31, 1973.

APPROVED:

1/4/73 (sgd.) Richard L. Seggel

Date Acting Assistant Secretary for Health

Panel Members

Chairman:

Broadus N. Butler, Ph.D.

President, Dillard University

2601 Gentilly Boulevard

New Orleans, Louisiana 70122

Members:

Mr. Ronald H. Brown

General Counsel

National Urban League

55 East 52nd Street

New York, New York 10022

Vernal Cave, M.D.

Director, Bureau of Venereal Disease Control

New York City Health Department

93 Worth Street

New York, New York 10013

Jean L. Harris, M.D., F.R.S.H.

Executive Director

National Medical Association Foundation, Inc.

1150 17th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Seward Hiltner, Ph.D., D.D.

Professor of Theology

Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

Jay Katz, M.D.

Professor (Adjunct) of Law and Psychiatry

Yale Law School

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

Jeanne C. Sinkford, D.D.S.

Associate Dean for Graduate and Postgraduate Affairs

College of Dentistry

Howard University

600 W Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Mr. Fred Speaker

Attorney at Law

2 North Market Square

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17108

Mr. Barney H. Weeks

President, Alabama Labor Council

AFL-CIO

1018 South 18th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35205

Final Report

Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad Hoc Advisory Panel

Report on Charge 1-A

Statement of Charge 1-A: Determine whether the study was justified in 1932

Background Data

The Tuskegee Study was one of several investigations that were taking place in the 1930’s with the ultimate objective of venereal disease control in the United States. Beginning in 1926, the United States Public Health Service, with the cooperation of other organizations, actively engaged in venereal disease control work.1 In 1929, the United States Public Health Service entered into a cooperative demonstration study with the Julius Rosenwald Fund and state and local departments of health in the control of venereal disease in six southern states:2 Mississippi (Bolivar County); Tennessee (Tipton County): Georgia (Glynn County); Alabama (Macon County); North Carolina (Pitt County); Virginia (Albermarle County). These syphilis control demonstrations took place from 1930–1932 and disclosed a high prevalence of syphilis (35%) in the Macon County survey. Macon County was 82.4% Negro. The cultural status of this Negro population was low and the illiteracy rate was high.

During the years 1928–1942 the Cooperative Clinical Studies in the Treatment of Syphilis3 were taking place in the syphilis clinics of Western Reserve University, Johns Hopkins University, Mayo Clinic, University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Michigan. The Division of Venereal Disease, USPHS provided statistical support, and financial support was provided by the USPHS and a grant from the Milbank Memorial Fund. These studies included a focus on effects of treatment in latent syphilis which had not been clinically documented before 1932. A report issued in 1932 indicated a satisfactory clinical outcome in 35% of untreated latent syphilitics.

The findings of Bruusgaard of Oslo on the results of untreated syphilis became available in 1929.4 The Oslo study was a classic retrospective study involving the analysis of 473 patients at three to forty years after infection. For the first time, as a result of the Oslo study, clinical data were available to suggest the probability of spontaneous cure, continued latency, or serious or fatal outcome. Of the 473 patients included in the Oslo study, 309 were living and examined and 164 were deceased. Among the 473 patients, 27.7 percent were clinically free from symptoms and Wassermann negative; 14.8 percent had no clinical symptoms with Wassermann positive; 14.1 percent had heart and vessel disease; 2.76 percent had general paresis and 1.27 percent had tabes dorsalis. Thus in 1932, as the Public Health Service put forth a major effort toward control and treatment much was still unknown regarding the latent stages of the disease especially pertaining to its natural course and the epidemiology of late and latent syphilis.

Facts and Documentation Pertaining to Charge 1-A

1. There is no protocol which documents the original intent of the study. None of the literature searches or interviews with participants in the study gave any evidence that a written protocol ever existed for this study. The theories postulated from time to time include the following purposes either by direct statement or implication:5–7

a. Study of the natural history of the disease.

b. Study of the course of treated and untreated syphilis (Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service of the United States 1935–36).

c. Study of the differences in histological and clinical course of the disease in black versus white subjects.

d. Study with an “acceptance” of the postulate that there was a benign course of the disease in later stages vis-a-vis the dangers of available therapy.

e. Short term study (6 months or longer) of the incidence and clinical course of late latent syphilis in the Negro male (From letter of correspondence from T. Clark, Assistant Surgeon General, to M. M. Davis of the Rosenwald Fund, October 29, 1932)—Original plan of procedure is stated herein.

f. A study which would provide valuable data for a syphilis control program for a rural impoverished community.

In the absence of an original protocol, it can only be assumed that between 1932 and 1936 (when the first report5 of the study was made) the decision was made to continue the study as a long-term study. The Annual Report of the Surgeon General for 1935–36 included the statement: “Plans for the continuation of this study are underway. During the last 12 months, success has been obtained in gaining permission for the performance of autopsies on 11/15 individuals who died.”

2. There is no evidence that informed consent was gained from the human participants in this study. Such consent would and should have included knowledge of the risk of human life for the involved parties and information re possible infections of innocent, non-participating parties such as friends and relatives. Reports such as “Only individuals giving a history of infection who submitted voluntarily to examination were included in the 399 cases” are the only ones that are documentable.5 Submitting voluntarily is not informed consent.

3. In 1932, there was a known risk to human life and transmission of the disease in latent and late syphilis* was believed to be possible. Moore3 1932 reported satisfactory clinical outcome in 85% of patients with latent syphilis that were treated in contrast to 35% if no treatment is given.

4. The study as announced and continually described as involving “untreated” male Negro subjects was not a study of “untreated” subjects. Caldwell8 in 1971 reported that: All but one of the originally untreated syphilitics seen in 1968–1970 have received therapy, although heavy metals and/or antibiotics were given for a variety of reasons by many non-study physicians and not necessarily in doses considered curative for syphilis. Heller6 in 1946 reported “about one-fourth of the syphilitic individuals received treatment for their infection. Most of these, however, received no more than 1 or 2 arsenical injections; only 12 received as many as 10.” The “untreated” group in this study is therefore a group of treated and untreated male subjects.

*Vonderlehr to T. Clark—Memorandum—June 10, 1932.

5. There is evidence that control subjects who became syphilitic were transferred to the “untreated” group. This data is present in the patient files at the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta. Caldwell8 reports 12 original controls either acquired syphilis or were found to have reactive treponemal tests (unavailable prior to 1953). Heller,6 also, reported that “It is known that some of the control group have acquired syphilis although the exact number cannot be accurately determined at present.” Since this transfer of patients from the control group to the syphilitic group did occur, the study is not one of late latent syphilis. Also, it is not certain that this group of patients did in fact receive adequate therapy.

6. In the absence of a definitive protocol, there is no evidence or assurance that standardization of evaluative procedures, which are essential to the validity and reliability of a scientific study, existed at any time. This fact leaves open to question the true scientific merits of a longitudinal study of this nature. Standardization of evaluative procedures and clinical judgment of the investigators are considered essential to the valid interpretation of clinical data.9 It should be noted that, in 1932, orderly and well planned research related to latent syphilis was justifiable since a. Morbidity and mortality had not been documented for this population and the significance of the survey procedure had just been reported in findings of the prevalence studies for 6 southern counties;1 b. Epidemiologic knowledge of syphilis at the time had not produced facts so that it could be scientifically documented “just how and at what stage the disease is spread.”* c. There was a paucity of knowledge re clinical aspects and spontaneous cure in latent syphilis3 and the Oslo study4 had just reported spontaneous remission of the disease in 27.7% of the patients studied. If perhaps a higher “cure” rate could have been documented for the latent syphilitics, then the treatment priorities and recommendations may have been altered for this community where funds and medical services were already inadequate.

*Letter from L. Usilton, VD Program 1930–32 and memorandum from Vonderlehr to T. Clark (Assistant Surgeon General) June 10, 1932.

The retrospective summary of the “Scientific Contributions of the Tuskegee Study” from the Chief, Venereal Disease Branch, USPHS (dated November 21, 1972) includes the following merits of the study:

Knowledge already gained or potentially able to be gained from this study may be categorized as contributing to improvements in the following areas:

1. Care of the surviving participants,

2. Care of all persons with latent syphilis,

3. The operation of a national syphilis control program,

4. Understanding of the disease of syphilis,

5. Understanding of basic disease producing mechanisms.

Panel Judgments on Charge 1-A

1. In retrospect, the Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro in Macon County, Alabama, was ethically unjustified in 1932. This judgment made in 1973 about the conduct of the study in 1932 is made with the advantage of hindsight acutely sharpened over some forty years, concerning an activity in a different age with different social standards. Nevertheless one fundamental ethical rule is that a person should not be subjected to avoidable risk of death or physical harm unless he freely and intelligently consents. There is no evidence that such consent was obtained from the participants in this study.

2. Because of the paucity of information available today on the manner in which the study was conceived, designed and sustained, a scientific justification for a short term demonstration study cannot be ruled out. However, the conduct of the longitudinal study as initially reported in 1936 and through the years is judged to be scientifically unsound and its results are disproportionately meager compared with known risks to human subjects involved. Outstanding weaknesses of this study, supported by the lack of written protocol, include lack of validity and reliability assurances; lack of calibration of investigator responses; uncertain quality of clinical judgments between various investigators; questionable data base validity and questionable value of the experimental design for a long term study of this nature.

The position of the Panel must not be construed to be a general repudiation of scientific research with human subjects. It is possible that a scientific study in 1932 of untreated syphilis, properly conceived with a clear protocol and conducted with suitable subjects who fully understood the implications of their involvement, might have been justified in the pre-penicillin era. This is especially true when one considers the uncertain nature of the results of treatment of late latent syphilis and the highly toxic nature of therapeutic agents then available.

Report on Charge 1-B

Statement of Charge 1-B: Determine whether the study should have been continued when penicillin became generally available

Background Data

In 1932, treatment of syphilis in all stages was being provided through the use of a variety of chemotherapeutic agents including mercury, bismuth, arsphenamine, neoarsphenamine, iodides and various combinations thereof. Treatment procedures being used in the early 1930’s extended over long periods of time (up to two years) and were not without hazard to the patient.10 As of 1932, also, treatment was widely recommended and treatment schedules specifically for late latent syphilis were published and in use.3–10 The rationale for treatment at that time was based on the clinical judgment “that the latent syphilitic patient must be regarded as a potential carrier of the disease and should be treated for the sake of the Community’s health.”3 The aims of treatment in the treatment of latent syphilis were stated to be: 1) to increase the probability of “cure” or arrest, 2) to decrease the probability of progression or relapse over the probable result if no treatment were given and 3) the control of potential infectiousness from contact of the patient with adults of either sex, or in the case of women with latent syphilis, for unborn children.

According to Pfeiffer (1935),11 treatment of late syphilis is quite individualistic and requires the physician’s best judgment based upon sound fundamental knowledge of internal medicine and experience, and should not be undertaken as a routine procedure. Thus, treatment was being recommended in the United States for all stages of syphilis as of 1932 despite the “spontaneous” cure concept that was being justified by interpretations of the Oslo study, the potential hazards of treatment due to drug toxicity and to possible Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions in acute late syphilis.12

Documented reports of the effects of penicillin in the 1940’s and early 1950’s vary from outright support and endorsement of the use of penicillin in late and latent syphilis,13–15 to statements of possible little or no value,16–17 to expressions of doubts and uncertainty18–19 related to its value, the potency of penicillin, absence of control of the rate of absorption, and potential hazard related to severe Herxheimer effects.

Although the mechanism of action of penicillin is not clear from available scientific reports of late latent syphilis, the therapeutic benefits were clinically documented by the early 1950’s and have been widely reported from the mid 1950’s to the present. In fact, the Center for Disease Control of the USPHS has reported treatment of syphilitic mothers in all stages of infection with penicillin as of 195320 and has demonstrated that penicillin is the most effective treatment yet known for neurosyphilis (1960).21

Facts and Documentation re Charge 1-B

1. Treatment schedules recommending the use of arsenicals and bismuth in the treatment of late latent syphilis were available in 1932.3 Penicillin therapy was recommended for treatment of late latent syphilis in the late 1940’s14–15 which was before it became readily available for public use (estimated to have been 1952–53).

2. It was “known as early as 1932 that 85% of patients treated in late latent syphilis would enjoy prolonged maintenance of good health and freedom from disease as opposed to 35 percent if left untreated.”3 Scientists in this study,5 reported in 1936, that morbidity in male Negroes with untreated syphilis far exceeds that in a comparable nonsyphilitic group and that cardiovascular and central nervous system involvements were two or three times as common. Moreover, Wenger,22 in 1950, reported: “We know now, where we could only surmise before, that we have contributed to their ailments and shortened their lives. I think the least we can say is that we have a high moral obligation to those that have died to make this the best study possible.” The effect of syphilis in shortening life was published from observations made by Usilton et al. in 1937.23 The study by Rosahn24 at Yale in 1947 reported strong clinical evidence that syphilis ran a more fatal course in Negroes than in Caucasians.

3. Reports regarding the withholding of treatment from patients in this study are varied and are still subject to controversy. Statements received from personal interviews conducted by Panel members with participants in this study cannot be considered as conclusive since there are varied opinions concerning what actually happened. In written letters and in open interviews, the panel received reports that treatment was deliberately withheld on the one hand and on the other, we were told that individuals seeking treatment were not denied treatment (in transcript and correspondence documents).

What is clearly documentable (in a series of letters between Vonderlehr and Health officials in Tuskegee taking place between February 1941 and August 1942) is that known seropositive, untreated males under 45 years of age from the Tuskegee Study had been called for army duty and rejected on account of a positive blood. The local board was furnished with a list of 256 names of men under 45 years of age and asked that these men be excluded from the list of draftees needing treatment! According to the letters, the board agreed with this arrangement in order to make it possible to continue this study on an effective basis. It should be noted that some of these patients had already received notices from the Local Selective Service Board “to begin their antisyphilitic treatment immediately.”

According to Wenger,22 the patients in the study “received no treatment on our recommendation.” At the present time, we know that most of the participants in this study received some form of treatment with heavy metals and/or antibiotics.8 Although the adequacy of treatment received is not known, it is clear that the treatment received was provided by physicians who were not a part of the study and who were individually sought by the individual patients related to their own medical symptoms and pursuit of treatment.

4. The five survey periods in this study occurred in 1932, 1938–39, 1948, 1952–53 and 1968–70.8–25 This study lacks continuity except through the public health nurse and at these isolated survey periods. In 1969 an Ad Hoc Committee reviewed the Tuskegee Study with the purpose: to examine data from the Tuskegee Study and offer advice on continuance of this study.

Participants of the February 6, 1969 meeting included:

Committee Members:

Dr. Gene Stollerman

Chairman, Dept. of Medicine

University of Tennessee, Memphis

Dr. Johannes Ipsen, Jr.

Professor

Dept. of Community Medicine

University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Dr. Ira Myers

State Health Officer

Montgomery

Dr. J. Lawton Smith

Associate Professor of Ophthalmology

University of Miami

Dr. Clyde Kaiser

Senior Member Technical Staff

Milbank Memorial Fund

New York City

Resource Persons:

Dr. Bobby C. Brown, VDRL, NCDC

Mrs. Eleanor V. Price, VD Branch, NCDC

Dr. Joseph Caldwell, VD Branch, NCDC

Dr. Paul Cohen, VDRL, NCDC

Dr. Sidney Olansky

Professor of Medicine

Dept. of Internal Medicine

Emory University Clinic, Atlanta

Recorders:

Dr. Leslie Norins

Chief, VDRL, NCDC

Mrs. Doris J. Smith

Secretary to Dr. Norins, VDRL, NCDC

Attending:

Dr. David J. Sencer

Director, NCDC

Dr. William J. Brown

Chief, VD Branch, NCDC

Dr. U. S. G. Kuhn, III, VDRL, NCDC

Miss Genevieve W. Stout, VDRL, NCDC

Dr. H. Bruce Dull

Assistant Director, NCDC

The meeting was convened at 1:00 p.m. and adjourned at 4:10 p.m.

A summary report of the meeting includes the following:

The purpose of the meeting was to determine if the Tuskegee Study should be terminated or continued.

Considerations were:

1. How the study was setup in 1932

2. Are the participants all available

3. How are the survivors faring

At the time of this study there were only seven patients whose primary cause of death was ascribed to syphilis.

It was determined that benefits to be achieved from the study at this time were:

1. Relationship of serology to morbidity from syphilis

2. Relationship of known pathology to syphilis

3. Various epidemiological considerations

Full treatment of the survivors was also considered and the following liabilities listed.

Danger of late Herxheimer’s reaction which would worsen or possibly kill those syphilitic patients suffering from cardiovascular or neurological conditions.

At this time it was mentioned that both Macon County Health Department and Tuskegee Institute were cognizant of the study.

The meeting was terminated with several salient points.

1. This type of study would never be repeated.

2. There were certain medical facts to be learned by continuing the present study.

3. Treatment for these patients was not indicated unless they had signs of active syphilitic disease.

4. More contact should be established between PHS and Macon County Health Department and Medical Society so they would cooperate in the continuance of the study.

It should be noted that the Committee was eminently represented from the medical community. However, legal representatives and others from the nonmedical community of scholars were not adequately represented for so sensitive a study. This is especially true since the Tuskegee Study was being continued at a time when Department of Health, Education, and Welfare guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects were being widely disseminated for compliance by all institutions receiving grant support. The three hours and ten minutes were not adequate for in-depth study of the broad issues, implications and ramifications of this study.

In 1970, Drs. Anne Yobs and Arnold L. Schroeter in separate memoranda (to the Director, Center for Disease Control and to the Chief, Venereal Disease Branch) recommended procedures for orderly termination of this study. Dr. James Lucas, Assistant Chief of the Venereal Disease Branch, in a memorandum to the Chief of the Venereal Disease Branch dated September 10, 1970 states: It must be fully realized that the remaining contribution from this study will be largely of historical interest. Nothing learned will prevent, find, or cure a single case of infectious syphilis or bring us closer to our basic mission of controlling venereal disease in the United States.

5. There is a crucial absence of evidence that patients were given a “choice” of continuing in the study once penicillin became readily available. This fact serves to amplify the magnitude of encroachment on the human lives and well-being of the participants in this study. This is especially significant when there is uncertainty as to the whole issue of “consent” of the participants.

Panel Judgments on Charge 1-B

The ethical, legal and scientific implications which are evoked from the facts presented in the previous section led the Panel to the following judgment:

That penicillin therapy should have been made available to the participants in this study especially as of 1953 when penicillin became generally available.

Withholding of penicillin, after it became generally available, amplified the injustice to which this group of human beings had already been subjected. The scientific merits of the Tuskegee Study are vastly overshadowed by the violation of basic ethical principles pertaining to human dignity and human life imposed on the experimental subjects.

Report on Charge 1

Summary

This section of the Advisory Panel’s report deals specifically with Charge Codes 1-A and 1-B.

Statement of Charge Codes

Charge 1-A. Determine whether the study was justified in 1932, and Charge 1-B. Determine whether it should have been continued when penicillin became generally available.

Introduction

The Background Paper on the Tuskegee Study, prepared by the Venereal Disease Branch of the Center for Disease Control, July 27, 1972, included the following statements:

“Because of the lack of knowledge of the pathogenesis of syphilis, a long-term study of untreated syphilis was considered desirable in establishing a more knowledgeable syphilis control program.”

“A prospective study was begun late in 1932 in Macon County, Alabama, a rural area with a static population and a high rate of untreated syphilis. An untreated population such as this offered an unusual opportunity to follow and study the disease over a long period of time. In 1932, a total of 26 percent of the male population tested, who were 25 years of age or older, were serologically reactive for syphilis by at least two tests, usually on two occasions. The original study group was composed of 399 of these men who had received no therapy and who gave historical and laboratory evidence of syphilis which had progressed beyond the infectious stages. A total of 201 men comparable in age and environments and judged by serology, history, and physical examination to be free of syphilis were selected to be the control group.”

Panel Conclusions re Charge 1-A and 1-B of the Tuskegee Study

After extensive review of the available documents, interviews with associated parties and pursuit of various other avenues of documentation, the Panel concludes that:

1. In retrospect, the Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro in Macon county, Alabama was ethically unjustified in 1932.

2. Because of the paucity of information available today on the manner in which the study was conceived, designed and sustained, scientific justification for a short-term demonstration study in 1932 cannot be ruled out. However, the conduct of the longitudinal study as initially reported in 1936 and through the years is judged to be scientifically unsound and its results are disproportionately meager compared with known risks to the human subjects involved.

3. Penicillin therapy should have been made available to the participants in this study not later than 1953.

The Panel qualifies its conclusions with several position statements summarized as follows:

a. The judgments in 1973 about the conduct of the Tuskegee Study in 1932 are made with the advantage of hindsight, acutely sharpened over some forty years concerning an activity in a different age with different social standards. Nevertheless one fundamental ethical rule is that a person should not be subjected to avoidable risk of death or physical harm unless he freely and intelligently consents. There was no evidence that such consent was obtained from the participants in this study.

b. History has shown that certain people under psychological, social or economic duress are particularly acquiescent. These are the young, the mentally impaired, the institutionalized, the poor and persons of racial minority and other disadvantaged groups. These are the people who may be selected for human experimentation and who, because of their station in life, may not have an equal chance to withhold consent.

c. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, placed in the perspective of its early years, is not an isolated event in terms of the generally accepted conditions and practices that prevailed in the 1930’s.

d. The position of the Panel must not be construed to be a general repudiation of scientific research with human subjects. It is possible that a scientific study in 1932 of untreated syphilis, properly conceived with a clear protocol and conducted with suitable subjects who fully understood the implications of their involvement, might have been justified in the pre-penicillin era because of the uncertain nature of results of treatment of late latent syphilis with the highly toxic therapeutic agents then available.

REFERENCES

1. Clark, T. The Control of Syphilis in Southern Rural Areas. Julius Rosenwald Fund, Chicago, 1932, p. 27.

2. Ibid., pp. 6–36.

3. Moore, Joseph Earle. Latent Syphilis Cooperative Clinical Studies in the Treatment of Syphilis. Reprint No. 45 from Venereal Disease Information, Vol. XIII, Nos. 8–12, 1932 and Vol. XIV, No. 1, 1933, pp. 1–56.

4. Bruusgaard, E. The Fate of Syphilitics Who are not Given Specific Treatment. Archiv tur Dermatologie und Syphilis 1929, 157, p. 309.

5. Vonderlehr, R. A., et al. Untreated Syphilis in the Male Negro. Venereal Disease Information 17:260–265, 1936.

6. Heller, J. R. and Bruyere, P.T.: Untreated Syphilis in Male Negro: II. Mortality During 12 Years of Observation. Venereal Disease Information 27: 34–38, 1946.

7. Shafer, J. K., Usilton, L. J., and Gleason, G. A. Untreated Syphilis in Male Negro: Prospective Study of Effect on Life Expectancy. Public Health Reports 69:684–690, 1954; Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 32:262–274, July 1954.

8. Caldwell, J. G., Price, E. V., Shroeter, A. L., and Fletcher, G. F. Aortic Regurgitation in a Study of Aged Males with Previous Syphilis. Presented in part at American Venereal Disease Association Annual Meeting, 22 June 1971.

9. Feinstein, A. R. Clinical Judgment. Baltimore, William and Wilkins Co., 1967, pp. 45–48.

10. Gaupin, C. E. The Treatment of Latent Syphilis. Kentucky Medical Journal 30: 74–77, February 1932.

11. Pfeiffer, A. Medical Aspects in the Prevention and Management of Late and Latent Syphilis. Psychiatric Quarterly 9: 185–193, April 1935.

12. Greenbaum, S. C. The “Bismuth Approach” in the Treatment of Acute (Late) Syphilis. Journal of Chemotherapy 13: 5–8, April 1936.

13. Stokes, J. H., et al. The Action of Penicillin in Late Syphilis. J.A.M.A. 126: 73–79, September 1944.

14. Dexter, D. C. and Tucker, H. A. Penicillin Treatment of Benign Late Gummatous Syphilis, Report of Twenty-one Cases. American Journal of Syphilis, Gonorrhea, and Venereal Disease 30: 211–226, May 1946.

15. Committee on Medical Research: The Changing Character of Commercial Penicillin with Suggestions as to the Use of Penicillin in Syphilis. U.S. Health Service and Food and Drug Administration. J.A.M.A. 131: 271–275, May 1946.

16. Barnett, C. W. The Public Health Aspects of Late Latent Syphilis. Stanford Medical Bulletin 10: 152–156, August 1952.

17. Reynolds, F. W. Treatment Failures Following the Use of Penicillin in Late Syphilis. American Journal of Syphilis, Gonorrhea, and Venereal Disease 32: 233–242, May 1948.

18. McElligott, G. L. M. The Management of Late and Latent Syphilis. British Medical Journal 1: 829–830, April 1953.

19. Barnett, C. W., Epstein, N. J., Brewer, A. F. et al. Effect of Treatment in Late Latent Syphilis. Arch Dermat Syph 69: 91–99, January 1954.

20. VD Fact Sheet, No. 10. U.S. Public Health Service Publication, December 1953, p. 20

21. VD Fact Sheet, No. 17. U.S. Public Health Service Publication, December 1960, p. 19.

22. Wenger, O. C. Untreated Syphilis in Negro Male. Hot Springs Seminar, 9-18-50 (From CDC Files).

23. Usilton, L. et al. A Tentative Death Curve for Acquired Syphilis in White and Colored Males in the United States. Venereal Disease Information 18: pp. 231–234, 1937.

24. Rosahn, P. D. Autopsy Studies in Syphilis. Journal of Venereal Disease Information 28: Supplement No. 21, pp. 32–39, 1949.

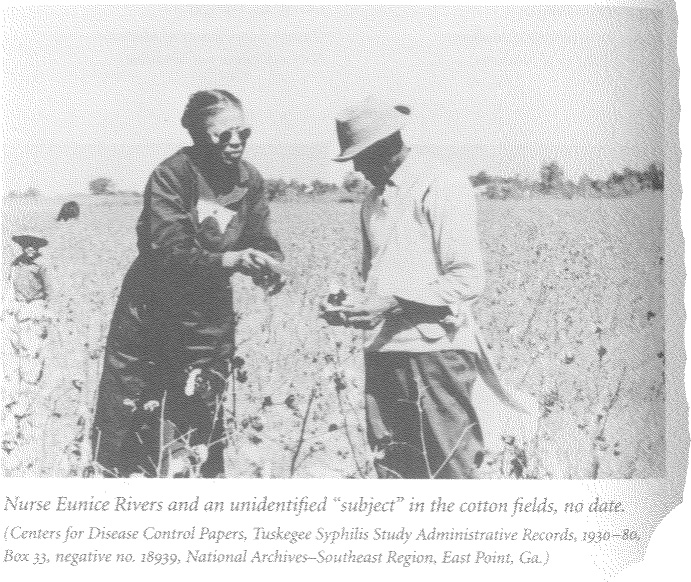

25. Rivers, E., Schuman, S., Simpson, L., and Olansky, S. Twenty Years of Follow-up Experience in a Long-Range Medical Study. Public Health Reports 68: (4), 391–395, April 1953.

Respectfully Submitted,

Ronald H. Brown

Jean L. Harris, M.D.

Seward Hiltner, Ph.D., D.D.

Jeanne C. Sinkford, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Fred Speaker

Barney H. Weeks

Approval with Reservations:

(See addendum for reservation statement)

Jay Katz, M.D.

Vernal Cave, M.D.

Abstention:

Broadus N. Butler, Ph.D.

Yale Law School, New Haven, Connecticut 06520

TO: THE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR HEALTH AND SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS

FROM: JAY KATZ, M.D.

TOPIC: RESERVATIONS ABOUT THE PANEL REPORT ON CHARGE 1

I should like to add the following findings and observations to the majority opinion:

(1) There is ample evidence in the records available to us that the consent to participation was not obtained from the Tuskegee Syphilis Study subjects, but that instead they were exploited, manipulated, and deceived. They were treated not as human subjects but as objects of research. The most fundamental reason for condemning the Tuskegee Study at its inception and throughout its continuation is not that all the subjects should have been treated, for some might not have wished to be treated, but rather that they were never fairly consulted about the research project, its consequences for them, and the alternatives available to them. Those who for reasons of intellectual incapacity could not have been so consulted should not have been invited to participate in the study in the first place.

(2) It was already known before the Tuskegee Syphilis Study was begun, and reconfirmed by the study itself, that persons with untreated syphilis have a higher death rate than those who have been treated. The life expectancy of at least forty subjects in the study was markedly decreased for lack of treatment.

(3) In addition, the untreated and the “inadvertently” (using the word frequently employed by the investigators) but inadequately treated subjects suffered many complications which could have been ameliorated with treatment. This fact was noted on occasion in the published reports of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and as late as 1971. However the subjects were not apprised of this possibility.

(4) One of the senior investigators wrote in 1936 that since “a considerable portion of the infected Negro population remained untreated during the entire course of syphilis . . . an unusual opportunity (arose) to study the untreated syphilitic patient from the beginning of the disease to the death of the infected person.” Throughout, the investigators seem to have confused the study with an “experiment in nature.” But syphilis was not a condition for which no beneficial treatment was available, calling for experimentation to learn more about the condition in the hope of finding a remedy. The persistence of the syphilitic disease from which the victims of the Tuskegee Study suffered resulted from the unwillingness or incapacity of society to mobilize the necessary resources for treatment. The investigators, the USPHS, and the private foundations who gave support to this study should not have exploited this situation in the fashion they did. Unless they could have guaranteed knowledgeable participation by the subjects, they all should have disappeared from the research scene or else utilized their limited research resources for therapeutic ends. Instead, the investigators believed that the persons involved in the Tuskegee Study would never seek out treatment; a completely unwarranted assumption which ultimately led the investigators deliberately to obstruct the opportunity for treatment of a number of the participants.

(5) In theory if not in practice, it has long been “a principle of medical and surgical morality (never to perform) on man an experiment which might be harmful to him to any extent, even though the result might be highly advantageous to science” (Claude Bernard 1865), at least without the knowledgeable consent of the subject. This was one basis on which the German physicians who had conducted medical experiments in concentration camps were tried by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal for crimes against humanity. Testimony at their trial by official representatives of the American Medical Association clearly suggested that research like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study would have been intolerable in this country or anywhere in the civilized world. Yet the Tuskegee study was continued after the Nuremberg findings and the Nuremberg Code had been widely disseminated to the medical community. Moreover, the study was not reviewed in 1966 after the Surgeon General of the USPHS promulgated his guidelines for the ethical conduct of research, even though this study was carried on within the purview of his department.

(6) The Tuskegee Syphilis Study finally was reviewed in 1969. A lengthier transcript of the proceedings, not quoted by the majority, reveals that one of the five members of the reviewing committee repeatedly emphasized that a moral obligation existed to provide treatment for the “patients.” His plea remained unheeded. Instead the Committee, which was in part concerned with the possibility of adverse criticism, seemed to be reassured by the observation that “if we established good liaison with the local medical society, there would be no need to answer criticism.”

(7) The controversy over the effectiveness and the dangers of arsenic and heavy metal treatment in 1932 and of penicillin treatment when it was introduced as a method of therapy is beside the point. For the real issue is that the participants in this study were never informed of the availability of treatment because the investigators were never in favor of such treatment. Throughout the study the responsibility rested heavily on the shoulders of the investigators to make every effort to apprise the subjects of what could be done for them if they so wished. In 1937 the then Surgeon General of the USPHS wrote: “(f) or late syphilis no blanket prescription can be written. Each patient is a law unto himself. For every syphilis patient, late and early, a careful physical examination is necessary before starting treatment and should be repeated frequently during its course.” Even prior to that, in 1932, ranking USPHS physicians stated in a series of articles that adequate treatment “will afford a practical, if not complete guaranty of freedom from the development of any late lesions.”

In conclusion, I note sadly that the medical profession, through its national association, its many individual societies, and its journals, has on the whole not reacted to this study except by ignoring it. One lengthy editorial appeared in the October 1972 issue of the Southern Medical Journal which exonerated the study and chastised the “irresponsible press” for bringing it to public attention. When will we take seriously our responsibilities, particularly to the disadvantaged in our midst who so consistently throughout history have been the first to be selected for human research?

Respectfully submitted,

(sgd.) Jay Katz, M.D.

II. Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations

A. Evaluation of Current DHEW Policies for the Protection of Human Research Subjects

1. No uniform Departmental policy for the protection of research subjects exists. Instead one policy governs “extramural” research—research supported by DHEW grants or contracts to institutions outside the Federal Government and conducted by private researchers—and another policy governs “intramural” research—research conducted by personnel of the Public Health Service. Furthermore, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations promulgated to protect subjects in drug research, whether or not supported by DHEW or conducted by the PHS, incorporate variations of their own. The lack of uniformity in DHEW policies creates confusion, and denies some subjects the protection they deserve.

Moving to the next higher level, no uniform Federal policies exist for the protection of subjects in Government-sponsored research. Other agencies wholly separate from DHEW—most notably, the Department of Defense—support or conduct human research. DHEW policies do not govern such research. Here too, the Federal Government’s failure to develop a uniform policy has been detrimental to the welfare of research subjects.

2. Under current DHEW policies for the protection of research subjects, regulation of research practices is largely left to the biomedical professions. Since the conduct of human experimentation raises important issues of social policy, greater participation in decision-making by representatives of other professions and of the general public is required.

3. The present reliance by DHEW on the institutional review committee as the primary mechanism for the protection of research subjects was an important advance in the continuing effort to guarantee ethical experimentation. Prior peer review of research protocols is a requirement which should be retained.

4. The existing review committee system suffers from basic defects which seriously undermine the accomplishment of the task assigned to the committees:

a. The governing standards promulgated by DHEW which are intended to guide review committee decisions in specific cases are vague and overly general.

b. No provisions are made for the dissemination or publication of review committee decisions. Their low level of visibility hampers efforts to evaluate and learn from committee attempts to resolve the complex problems of human research.

c. Although the informed consent of the research subject is one of the most important requirements of research ethics, DHEW policies for obtaining consent are poorly drafted and contain critical loopholes. As a result, one crucial task of institutional review committees—the implementation of the informed consent requirement—is commonly performed inadequately. In particular, consent is far too often obtained in form alone and not in substance.

d. DHEW policies do not give sufficient attention to the protection of such special research subjects as children, prisoners and the mentally incompetent. The use of these subjects in human experimentation presents grave dangers of abuse.

e. The obligation of institutional review committees to conduct continuing review of research projects after their initial approval is undefined and as a consequence often neglected.

f. Inefficient utilization of institutional review committees contributes to their ineffectiveness. Committees are overburdened with a variety of separate functions, and could operate best if their tasks were narrowly defined to encompass mainly the implementation of research policies adequately formulated by others.

g. Effective procedures for enforcing DHEW policies, when those policies are disregarded, have not been devised.

5. No policy for the compensation of research subjects harmed as a consequence of their participation in research has been formulated, despite the fact that no matter how careful investigators may be, unavoidable injury to a few is the price society must pay for the privilege of engaging in research which ultimately benefits the many. Remitting injured subjects to the uncertainties of the law court is not a solution.

B. Policy Recommendations

1. Congress should establish a permanent body with the authority to regulate at least all Federally supported research involving human subjects, whether it is conducted in intramural or extramural settings, or sponsored by DHEW or other government agencies, such as the Department of Defense. Ideally, the authority of this body should extend to all research activities, even those not Federally supported. But such a proposal may raise major jurisdictional problems. This body could be called the National Human Investigation Board. The Board should be independent of DHEW, for we do not believe that the agency which both conducts a great deal of research itself and supports much of the research that is carried on elsewhere is a position to carry out dispassionately the functions we have in mind. The members of the Board should be appointed from diverse professional and scientific disciplines, and should include representatives from the public at large.

2. The primary responsibility of the National Human Investigation Board should be to formulate research policies, in much greater detail and with much more clarity than is presently the case. The Board must promulgate detailed procedures to govern the implementation of its policies by institutional review committees. It must also promulgate procedures for the review of research decisions and their consequences. In particular, this Board should establish procedures for the publication of important institutional committee and Board decisions. Publication of such decisions would permit their intensive study both inside and outside the medical profession and would be a first step toward the case-by-case development of policies governing human experimentation. We regard such a development, analogous to the experience of the common law, as the best hope for ultimately providing workable standards for the regulation of the human experimentation process.

3. The National Human Investigation Board should develop appeals procedures for the adjudication of disagreements between investigators and the institutional review committees.

4. The National Human Investigation Board should also develop a “no fault” clinical research insurance plan to assure compensation for subjects harmed as a result of their participation in research. Institutions which sponsor Federally supported research activities should be required to participate in such a plan.

5. With the establishment of adequate policy formulation and review mechanisms, the structure and functions of the institutional review committee should be altered to enhance the effectiveness of prior review. In place of the amorphous institutional review committee as it now exists, we propose the creation of an Institutional Human Investigation Committee (IHIC) with two distinct subcommittees. The IHIC should be the direct link between the institution and the National Human Investigation Board, and should establish local regulations consistent with national policies. The IHIC should also assume an educational role in its institutions, informing participants in the research enterprise of their rights and obligations. The implementation of research polices should be left to the two subcommittees of the IHIC:

a. A Protocol Review Group (PRG) should be responsible for the prior review of research protocols. The PRG should be composed mainly of competent biomedical professionals.

b. A Subject Advisory Group (SAG) should be responsible for aiding subjects in their decision-making whenever they request its services. Subject must be made aware of the existence of the SAG. The primary concern of the SAG should be with procedures for obtaining consent, and with the quality of consents obtained. The SAG should be composed of both professionals and laymen.

Conclusion

Human experimentation reflects the recurrent societal dilemma of reconciling respect for human rights and individual dignity with the felt needs of society to overrule individual autonomy for the common good. Throughout this report we have expressed our concern for the lack of attention which has been given to the protection of the rights and welfare of human subjects in research. Society can no longer afford to leave the balancing of individual rights against scientific progress to the scientific community alone. The revelations of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study once again dramatically confirmed this conclusion.

We offer our far-reaching proposals in the hope that the decision-making process for human research will become more open and more effectively regulated. We have amply documented the need for implementing this most basic recommendation. Precise rules and efficient procedures, however, are not by themselves proof against a repetition of Tuskegee. For, however well designed the system of regulation, the danger of token adherence to ethical standards and evasion in the guise of flexibility will persist. Ultimately, the spirit in which an aware society undertakes to use human beings for research ends will determine the protection which those human beings will receive. Therefore, we have urged throughout a greater participation by society in the decisions which affect so many human lives.

Respectfully submitted,

Ronald H. Brown

Vernal Cave, M.D.

Jean L. Harris, M.D.

Seward Hiltner, Ph.D., D.D.

Jay Katz, M.D.

Jeanne C. Sinkford, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Fred Speaker

Barney H. Weeks

Abstention:

Broadus N. Butler, Ph.D.