The “Tuskegee Study” of Syphilis

Analysis of Moral versus Methodologic Aspects

On July 26, 1972, an article was published in the New York Times entitled “Syphilis victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 years” [1]. Thirteen articles had been published since 1936 in seven major American medical journals about various aspects of this investigation, and the reporter did not imply that it had been conducted in secret [2–13]. However, her article was the instrument which began to focus attention on it outside of a rather small scientific community. Criticisms of the investigation were quickly aroused, particularly concerning ethical questions inherent in its conduct. Two weeks after the newspaper article appeared TIME magazine stated:

At the time the test began, treatment for syphilis was uncertain at best … but in the years following World War II, the PHS’s test became a matter of medical morality. Penicillin had been found to be almost totally effective against syphilis.… But the PHS did not use the drug on those participating in the study unless the patients asked for it. Such a failure seems almost beyond belief or human compassion [14].

In a publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People we read 8 months later:

Some 41 deliberately untreated victims of a carefully planned episode in human experimentation, together with a like number of heirs of those who failed to survive, have filed a complaint for 1.8 billion dollars in Alabama Federal Court. The plaintiffs were the survivors of the Tuskegee, Alabama syphilis experiment, in which 399 victims of the disease were left untreated and uninformed of the nature of their illness as part of a government-sponsored program [15].

A more general article about human experimentation stated that:

The wound to be avoided is human experimentation that offends the public’s sense of decency, such as the now notorious Tuskegee study, in which over 400 black men with syphilis went untreated for up to 40 years so that experimenters could study the natural course of the illness [16].

Dr. Thomas Benedek is a medical historian and professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Originally published in the Journal of Chronic Diseases 31 (1978): 35–50. Reprinted by permission of Elsevier Science.

These examples from the flurry of attacks on this investigation pertain entirely to its ethical implications and not to its scientific validity or value. This has been true of most of the criticisms. To review so protracted a medical undertaking fairly we must consider not only the research methodology that was prevalent at the inception of the investigation, but also the extent and reliability of the information about the subject to be investigated, as well as factual, methodologic and attitudinal changes which came about during its course.

Ethical and Methodologic Background

The clinical description of diseases was revolutionized in 1820–30 by Pierre C. A. Louis (1787–1872) in Paris when he introduced “the numerical method” to approach objectivity. Among the important principles of clinical investigation to which he called attention was that “we ought to know the natural progress of the disease, in all its degrees, when it is abandoned to itself” [17]. David W. Cheever (1831–1915), a Boston surgeon and a disciple of Louis in an essay on the applicability of statistics to the observation of diseases in 1860 formulated some of the philosophic problems which are central to the present article:

By the natural history of disease we mean the succession of phases which it exhibits when left to itself, uncomplicated by other morbid processes, and unmolested by active treatment.

Such knowledge (of the natural history) is, from the very nature of things, very difficult to acquire. The accumulated errors of the past, and the ever present obstacles of interest, prejudice and partiality, constantly impede our progress.… Most diseases are subjected to so active treatment, as must at once vitiate the result. The practitioner’s own conscientious scruples against leaving any cases to the care of Nature alone, from the fear, magnified by his previous teaching, that he might be injuring his patients: the non-perception of the utility of the knowledge to be so acquired, and the dread of being exposed to the charge of malpractice all operate against obtaining a knowledge of the natural history of disease [18].

Philosophically, Cheever proved to be nearly a century ahead of his time. With the possible exception of an earlier decline in treatment that is “so active” as to be more injurious than the disease, his cautions remained unheeded until the 1940s, when the importance of careful planning of clinical experiments so as to maximize the yield of interpretable results began to be recognized [19]. This resulted in the common use of “control groups” of subjects who received either nothing or a substance known to the investigator to be inert. The control groups permitted at least brief periods of the natural history of diseases to be observed in detail. However, one may conclude that the uninfluenced course of diseases has more often been recognized in retrospect, when it was realized that various treatments had been both innocuous and ineffective. The urge to treat and its potentially counterproductive consequences were first considered in some detail by Eugene Bleuler (1857–1939), a Swiss psychiatrist [20]. However, he also did not analyze the ethical implications of withholding therapy.

Recognition that there are ethical corollaries to the use of “control” subjects was not simultaneous with this advance in clinical experimentation. According to the report of the Judiciary Council of the American Medical Association of Dec. 10, 1946, experiments on human subjects, in order to conform to the ethics of the Association, must satisfy three requirements: (1) the voluntary consent of the person on whom the experiment is to be performed must be obtained, (2) the danger of each experiment must be previously investigated by animal experimentation, (3) the experiment must be performed under proper medical protection and management [21]. The implications of non-treatment were not considered.

The code of permissible medical experiments which was published in 1947 as an outcome of the Nuremberg war crimes trial states in the third of its ten paragraphs that “The experiment should be based upon … a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study” [22]. It also fails to concern itself with problems inherent in learning that natural history.

In 1948 A. C. Ivy reviewed the history and ethics of the use of human subjects in medical experiments [23]. He neither alluded to the Tuskegee Study or cited concepts that are more closely relevant to it than the foregoing opinion of the A.M.A. Judicial Council.

The notion that withholding treatment for the sake of the design of an experiment has ethical connotations was novel when A. B. Hill, a pioneer English biostatistician, discussed it in 1951. In commenting about the allocation of subjects to experimental groups, he stated that:

It should be noted that by non-treatment is not implied no treatment. Almost always, the question at issue is, does this particular form of treatment offer more than the usual orthodox treatment. The contrast is not, and usually cannot ethically be with no treatment [24].

Immediate Background of the Tuskegee Study

The foregoing brief citations demonstrate that there were virtually no philosophic guidelines in 1930 to influence the formulation of a prospective study of patients with an untreated chronic disease. Only one example existed. The history of this, including recognition of some of its shortcomings, was the theoretical basis from which the Public Health Service investigators began.

The story of this model started in 1890, not with an investigation, but with a policy change by Dr. Caesar Boeck (1845–1917), the professor of dermatology at the University of Oslo. He stopped using the mercury treatment of syphilis that had been employed since the 16th century. According to J. E. Bruusgaard (1869–1934), who then was one of the Boeck’s assistants, and eventually succeeded him, his attitude toward the treatment of syphilis had become that:

The specific measures, potassium iodide and mercury, have a good effect on the clinical symptoms. They are, however, unable to fully cure the disease, and disturb the regulating effect of the body as well as its own healing power. The disease takes an atypical course, which frequently has the consequence of serious visceral manifestations, especially in the central nervous system. Only when the patient is overcome in the battle against the syphilitic virus are the specific measures indicated and must then be given in “powerful” doses [25].

Thus, Boeck did not act on a premise that mercury is entirely ineffective, but rather that it is undesirable because it interferes with what we would call immune mechanisms to a greater extent than it affects the pathogen. He continued to administer iron and quinine, which were employed as non-specific tonics for a host of complaints. Between January 1891 and December 1910, 2181 patients were diagnosed in Boeck’s department to have syphilis and were not given the standard treatment of the time. Ninety % of the patients were hospitalized, usually for several months. Most of the 20 yr collection period had passed before 1906, when the two principal methods of laboratory diagnosis, dark field microscopy to prove the etiology of the primary lesion, and the Wassermann reaction to identify the disease after the primary lesion had resolved, were discovered. In view of the vast experience of the physicians this defect probably invalidated very few of the records. The policy of non-treatment was ended a few months after arsphenamine was introduced, because Boeck quickly became convinced that a really effective therapeutic agent now was at hand.

The clinical records that were generated during those 20 yr constituted a resource in which the natural history of syphilis could be studied, particularly because the patient population was rather homogeneous and not very mobile. The potential research value of these records was recognized by Bruusgaard after he had succeeded Boeck. Between 1925 and ’27, 473 patients (21.6%) were selected for review. The selection tended to be weighted in favor of inclusion of the more severely affected, because they were more likely to have remained under medical care and therefore were easier to locate [26]. 164 patients had died (40 autopsies), and in 70% of these syphilis was not causally implicated in the deaths. Three hundred and nine patients were re-examined. It was particularly remarkable in view of the probable bias in the case selection that 65% of these, and 73% of the subgroup who had had syphilis for at least 20 yr, were free of symptoms. Furthermore, 66% of the asymptomatic cases had a negative Wassermann reaction. If the symptom-free, sero-negative cases are defined as having undergone “spontaneous cures,” then 43% of the 309 fell into this category [25].

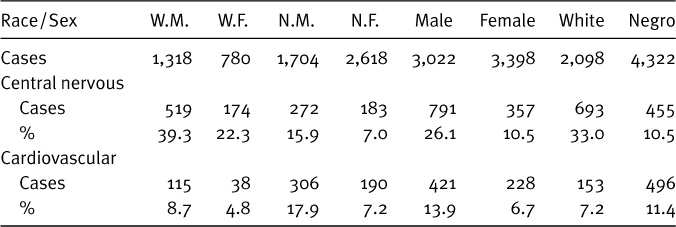

TABLE 1. Sex and Race Related Manifestations in 6,420 Cases of Late Syphilis

Adapted from Table 6. [26].

One other relevant piece of information about the natural history of syphilis was that there are definite sex-related and probable race-related differences in the occurrence of involvement of the central nervous and cardiovascular systems. Both kinds of tertiary manifestations occur more frequently in men than in women. However, syphilis of the central nervous system appears to be more prevalent among white than among Negro patients, while the opposite is true of cardiovascular involvement [27] (Table 1).

What was the state of anti-syphilitic therapy in the late 1920s? Arsphenamine had been introduced in 1910 [28], soon followed by related arsenical compounds which were hoped to be more stable and safer. In 1922 compounds of bismuth were introduced to supplement the arsenicals as well as the mercurials which, after more than four centuries of use, were not easily discarded [29, 30]. Most therapeutic regimens consisted of alternating periods of administration of an arsenical and a bismuth preparation, often also still using a mercurial. An expert opinion in 1926 was that:

The optimal amount of treatment for early syphilis with the plan advocated appears to be a full year of treatment after the serology of blood and spinal fluid have become and have remained negative, excepting only seronegative primary syphilis, in which a three course treatment, lasting 9 months, apparently produces satisfactory results [31].

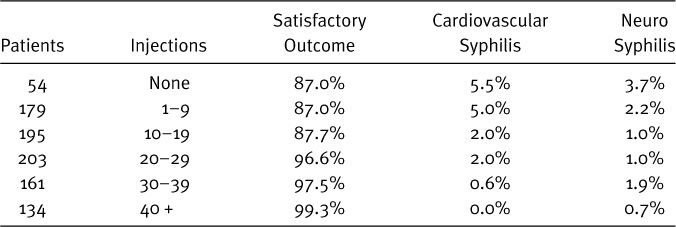

In 1939, 60 weeks of uninterrupted metallotherapy was recommended for early syphilis, and more complicated regimens to treat the tertiary manifestations [32]. Table 2 presents data which indicate that a shorter course of treatment would serve about as effectively and supports the opinion that was widely held that twenty injections of an arsenical provide the minimum amount of medication to affect the prognosis.

TABLE 2. Outcome of Syphilitic Patients Observed for 5 + Yr in Relation to Number of Arsenical Injections Received*

*Diagnosed as latent syphilis at Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1914–1934. Adapted from Tables 9 and 10. [33].

It also shows that only one syphilitic patient out of eight who was observed for 5 yr or more was healthier with “adequate” treatment than with little or no treatment [33].

Adverse reactions to the medications were the most commonly stated reason for failure to complete a course of treatment, followed by the inconvenience of the frequent visits that were required [34]. Toxic reactions occurred in about 15% of the patients, and the fatality rate from arsphenamine and neoarsphenamine was as high as 1% (12 of 1160 cases) [35, 36].

In 1930, when the decision was made in the U.S. Public Health Service to initiate another investigation of untreated syphilis, the paper Bruusgaard had published in 1929 constituted the only pertinent literature. It suggested that syphilis tends to run a rather benign course, but suffered from the lack of laboratory confirmation of the initial diagnosis and lack of randomisation of the patient sample that was traced. In view of the expense, hazards, and poor completion rate of treatment, a prospective investigation of the natural course of syphilis was determined to be desirable, in particular to develop a standard against which results of new forms of treatment could be compared.

Coincidentally, the Julius Rosenwald Fund in 1930 selected one rural county in each of six southern States in which to conduct demonstration venereal disease control projects. The highest prevalence of positive tests for syphilis among these six was found in Macon County, AL. Of 3684 Black inhabitants tested, 39.8% had a positive Wassermann reaction. Only 2% of the positive reactors gave a history of having received anti-syphilitic treatment, and as a result of the survey 95% were begun on therapy with neoarsphenamine and mercury [37].

The Tuskegee Study

The following review is based on the published reports of the investigators and on correspondence which is now preserved in the National Library of Medicine. NO comprehensive report has been published either by the sponsoring agency (Public Health Service) or by any of the participating investigators. Statistical information as published is not entirely consistent because of “different interpretations by various clinicians and analysis in regard to the criteria set up for the selection of study patients,” [10] and, therefore, a few compromise figures are used. The two principal events which occurred while the investigation was in progress that might have resulted in its revision or termination: the report of the Cooperating Clinical Group in 1934 and the discovery of the efficacy of penicillin in 1943, will be considered in their chronologic sequence.

The following factors, at least, need to be considered in planning a chronic investigation, and should be kept in mind in regard to the study under review.

(1) Are we certain that information we propose to seek does not already exist? (2) Are the questions posed in such a way that the results are likely to answer them? In other words, will the design of the experiment yield a maximum amount of information? (3) Can generalizations be made from information obtained from the experimental subjects, or do we know in advance that the data will largely be group specific? (4) Is new information likely to be obtained efficiently, and is it likely to be sufficiently important to justify the expenditures? (5) Is the proposed mechanism—availability of suitable subjects, staffing and funding—adequate to accomplish the experiment as it has been designed? (6) Has adequate consideration been given to potential hazards to the subjects and/or staff and have they been made aware of these and of their option not to participate in advance?

Because of the results of the Rosenwald Fund study, the Public Health Service chose Macon County, AL, in which to conduct a similar survey in 1931. This time 4400 Black residents who were at least 18 yr of age were tested. Two positive serologic tests for syphilis (Kolmer and Kahn) were found in 22.5% of the entire group and in 26.5% of the 1782 men who were at least 25 yr of age [8]. The difference between 39.8% and 22.5% probably is mainly explained by the exclusion from the second survey of a large number of children with congenital syphilis. According to the report of the Rosenwald Fund, the mean prevalence of congenital syphilis among those surveyed in the six counties was 28% with the unexplained greatest prevalence in Macon County—62%! Of the population of this county 82% was Black, and most were tenant farmers who were not likely to leave the area [8, 38]. In 1930 there were fifteen white physicians practicing medicine privately in the county [38], and in 1932 there were only nine [8], but at both times there was only one Black physician. The major landmark of the region was the Tuskegee Institute (founded in 1881), and this is why the investigation came to be called the Tuskegee study.

The starting date of the investigation was Jan. 1933. The subjects had been selected during that and the previous winter. All that can be concluded from the publications in regard to case selection is that 84.5% of the potential subjects who met the required criteria were entered into the Study. They initially comprised 399 men who were at least 25 yr of age, had two positive serologic tests for syphilis but no primary lesion, and gave no history of having received treatment. Tertiary syphilis was diagnosed in 11.5% of these subjects. Men who were found during the case selection process to have primary syphilis were begun on treatment and were excluded from the Study. The exclusion of women was not explained, but presumably was decided upon to avoid abetting the occurrence of congenital syphilis. Two series of control subjects were selected: 201 age-matched non-syphilitic men and 275 men who had received an inadequate number of arsphenamine injections during the first 2 yr after the diagnosis of syphilis had been made [2, 2a].

The only comment about the rationale of the investigation which the investigation ever published is the following:

As the result of surveys made a few years ago in southern rural areas it was learned that a considerable portion of the infected Negro population remained untreated during the entire course of syphilis. Such individuals seemed to offer an unusual opportunity to study the untreated syphilitic patients from the beginning of the disease to the death of the infected person. An opportunity was also offered to compare the syphilitic process uninfluenced by modern treatment with the results attained when treatment has been given [2, 2a].

A letter from the first director of the Study, Assistant Surgeon General R. A. Vonderlehr (1897–1973) to Dr. A. V. Deibert, to whom had been assigned the task of adding subjects to the Study, dated Dec. 5, 1938, reveals four attitudinal and factual elements about the Tuskegee Study which have not been published: that it was initiated without a long range plan, that the gathering of partially treated subjects had been fortuitous, why there had been more of these than untreated subjects, and why they were not deemed important to the Study:

when the study was started in the fall of 1932 no plans had been made for its continuation and a few patients were treated before we fully realized the need for continuing the project on a permanent basis. Second, it was difficult to hold the interest of the group of Negroes in Macon County unless some treatment was given. This was particularly true in the patients with early syphilis. In consequence, we treated practically all of the patients with early manifestations and many of the patients with latent syphilis.… I doubt the wisdom of bothering to examine the treated individuals carefully because we already have in the clinic of the Cooperative Clinical Group a considerable number of Negro males in the proper age groups who have received inadequate treatment and who are under observation [39].

Thus, the partially treated group of 275 men was not reported on after 1936. Whether an effort was made to have them complete their courses of treatment is unknown. It also is not clear when the decision was made to convert the data collection of 1932–33 into a chronic investigation. According to a report in 1953, “each of the patients was followed up with an annual blood test and, whenever the Public Health Service physicians came to Tuskegee, physical examinations were repeated” [6]. Twenty years later, another of the investigators construed that “At approximately 5-yr intervals, follow-up clinical and laboratory evaluations of these men have been conducted” [40]. Actually, clinical reexaminations, some of which were spread over 2 yr, were completed in 1939, ’48, ’52, ’54, ’63 and ’70. In 1956 it was stated that “since 1939 annual serologic examinations have been attempted” [11]. Data on the number of serologic examinations that were conducted are not available, but it is known that improved methods were introduced periodically, such as the T. pallidum immobilization test which the investigators began to use in 1952 [11]. Autopsies were performed at the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital and the tissues were sent to the Public Health Service laboratories in Washington, D.C. (later in Bethesda, MD) for microscopic examination.

The investigators never commented in a publication about budgetary constraints on their work. However, their correspondence reveals some of the consequences which must inevitably have resulted from the woefully inadequate total budgets of the Venereal Diseases Division of the Public Health Service. This deteriorated from its pre-1939 high of $1,000,000 in fiscal 1920 to a nadir of $58,808 in fiscal 1935, followed by an appropriation of $80,000 in each of the next 3 yr [41]. The more important of two examples pertains to the performance of autopsies. Whether or not an administrative procedure had been sought, none was found whereby the P.H.S. would pay for autopsies, which were a very important component of the total investigation. Therefore, financial support was requested at the outset from a private philanthropic organization, the Milbank Memorial fund, which then subsidized this segment of the Study throughout its course. Until 1952 the grant was $50 per autopsy, of which the pathologist,* at the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Hospital received $15. The remainder largely went to the undertaker [42]. For the next 13 yr the grant was increased to $100, of which the pathologist received $25. As recently as 1965 the chief of the Venereal Disease Division again begged that “Although I hesitate to presume on your generosity, I wonder if Milbank would consider increasing its allocation of $100.00 per autopsy to $175.00” [43].

*Dr. J. J. Peters performed the autopsies until 1963, when he retired. He was a diplomate of the American Board of Radiology.

Evidence that even expenditures of petty cash caused concern is shown in a letter in 1938 about the cost of mailing serum specimens from AL to the P.H.S. laboratory in New York:

Dr. Mahoney informs me that the blood sera is (sic) arriving in New York in a satisfactory condition. I was rather shocked at the cost involved in sending the sera by airmail and special delivery, this averaging about $1.50 per mailing tube containing the sera of 7 or 8 patients [44].

The only adjustment in the composition of the two groups of men who remained under observation was made in 1938, during the first reevaluation. At that time 43% of the syphilitic patients who were reexamined had received at least one injection of an anti-syphilitic drug. Twelve had received ten or more injections and were therefore removed from the Study [4]. Fourteen men who had latent syphilis and had not been examined before 1933 were added.

How many control subjects contracted syphilis during the course of the investigation, or even before its inception, never was clarified. In August 1942 Deibert wrote to Dr. M. Smith, another P.H.S. Physician:

During the reevaluation of the study in 1939 there were approximately fifteen of the control cases who were found to have either clinical or serologic evidence of a syphilitic infection. The discovery of these cases was largely due to the increased sensitivity of laboratory tests performed at that time. I would prefer that these cases remain untreated. Patients in the control group who were infected after 1939 should be treated [45].

In the preceding week Vonderlehr had in part overruled Deibert, having instructed Smith that all control subjects who had acquired syphilis since the Study began should be given appropriate treatment [46]. The number of these cases was not revealed. The only published statement was that “Also, a small number of patients who were included in the original non-syphilitic control group acquired syphilis during the period between the two examinations,” (i.e. 1938 and 1946) [4].

The Relation of the Cooperating Clinical Group Report to the Tuskegee Study

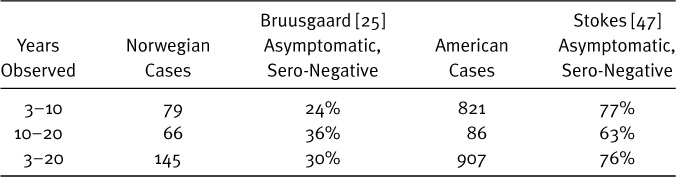

In 1934, the year after the Tuskegee Study was begun, a group of American syphilologists organized as the ‘Cooperating Clinical Group,’ published their findings from a multicenter study of the effectiveness of the treatment of early syphilis. The data of Bruusgaard were used for comparisons. Only 20% of this composite group of patients remained under observation for as long as 2 yr, and only 4% were available 5–10 yr after the diagnosis had been made. Even though the regimens of metallo-therapy that were employed by the several participants varied considerably, Table 3 shows clearly that the cure rate exceeded the rate of spontaneous resolutions among the Oslo cases. The greater proportion of “satisfactory outcome” without adequate treatment shown in Table 2 (87%), than in the untreated (24%, or treated cases 77%), in Table 3 is attributable to differences in criteria. The former study required absence of clinical progression of symptoms for at least 5 yr and normal spinal fluid, but not necessarily a negative serologic status of the blood [33], while the latter two required negative serologic blood tests. Clinical findings of syphilitic involvement of the nervous system were about three times as frequent, and skin or skeletal involvement were twenty times as common in the untreated subjects in Oslo as in the treated American patients, albeit after a much longer time. No difference was found in the occurrence of heart disease, which was infrequent in both groups. The authors concluded that

TABLE 3. Comparison of Spontaneous “Cure” Rate of Norwegian Syphilitics and Response of American Syphilitics to Metallo-Therapy

While the relative benignity of many aspects of untreated syphilis is conceded, the results … fully justify adequate and systematic modern treatment for early syphilis [47].

The Tuskegee investigators only once alluded to any of the data that were published by the Cooperating Clinical Group [3]. They did not discuss whether the therapeutic results bore any relevance to the ethical question of withholding therapy. However, it must be remembered that the C.C.G. demonstrated that various treatment programs were superior to no treatment specifically when they were initiated during an early phase of the disease, preferably within the first month, and at least in the first half year. That investigation was not designed to determine the effect of treatment when it is begun as late in the course of syphilis as all of the Tuskegee subjects were. Based on the reevaluation of 534 patients at least 5 yr after the completion of some form of metallo-therapy (mean follow-up 10.8 yr) at one of the Cooperating Clinics (Johns Hopkins Hospital), P. Padget in 1940 partially disagreed with the conclusion of the C.C.G. report. He concluded that “The palpable inferiority of irregular and intermittent treatment strongly suggests that, if continuous treatment cannot be given, no treatment is the desideratum” [48].

A study of the mortality of syphilitic patients, based on data from the C.C.G. study was published in 1937 [49]. The Tuskegee investigators could also have cited this to support the continuation of their project, but did not. In the five clinics whose patients had been under treatment or observation for at least 6 months there was a mean decrease of life expectancy between the ages of 30–60 yr of 7.1 yr for Negroes and 4.8 yr for white men with syphilis, equivalent to 30.5% and 17.3% of their respective life expectancies. The mortality data of the Tuskegee Study during its first 12 yr showed a decrease of the life expectancy in the same age group of Negro men with syphilis of only 4.6 yr or 20% [3]. Thus, a smaller detrimental effect was found in the presumptively untreated Tuskegee subjects than in a similar group of patients who had been at least partially treated.

The Tuskegee Study: Social and Legal Aspects

The most persistently made criticism of the Tuskegee Study has been that the subjects did not consent to participate on the basis of having been provided with adequate information. This attitude is expressed twice in the report of the panel which was appointed by the Secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1972 to evaluate the project. To wit:

The most fundamental reason for condemning the Tuskegee Study at its inception and throughout its continuation is not that all the subjects should have been treated, but rather that they were never fairly consulted about the research project, its consequences for them, and the alternatives available to them. Those who for reasons of intellectual incapacity could not have been so consulted should not have been invited to participate in the study [50a].

If the requirement of informed consent is to be taken seriously, should impoverished and uneducated Blacks from rural Alabama have been selected as subjects in the first place? Or should a concerted effort have been made to find subjects from among the most educated within the population at large, or at least to select from the given subgroup those subjects most capable of giving “informed consent?” Put more generally … One should look for subjects among the most highly motivated; the most highly educated, and the least ‘captive’ members of the community [50b].

The investigators made only two brief comments about effects of the psychosocial status of the subjects on the Study. In the first publication it was mentioned that

We had considerable difficulty in taking the histories of syphilitic Negro males. The average Negro is a most congenial person and he has a tendency to agree with almost anything that one wishes him to agree with. We spent an hour or more getting each one of these histories [2a].

The attempt to please someone who is perceived as an authoritarian figure is a common reaction under most circumstances. I doubt that the responses would have differed much had the interviews been conducted by Black physicians, since they too would have appeared as figures of authority. However, the rather good success in maintaining contact with the subjects during the first two decades of the Study has been credited to the work of one Black nurse, a graduate of the Tuskegee Institute [6]. In this social context the problem of obtaining a reliable history was the same as the problem of obtaining a considered decision whether to participate in a program which promised little inconvenience and some rewards. While these may appear pathetically modest to us, they were significant in this society.

Because of the low educational status of the majority of the patients, it was impossible to appeal to them from a purely scientific approach. Therefore, various methods were used to maintain and stimulate their interest. Free medicines,* burial assistance or insurance, free hot meals on the days of examination, transportation to and from the hospital, and an opportunity to stop in town on the return trip … all helped [6].

The investigators sought to take advantage of a deprived socio-economic situation, which included a paucity of medical care. They did not attempt to take from the subjects of their investigation any medical care of which they might ordinarily avail themselves. However, in order to preserve the investigation so far as possible they did take one step to prevent the systematic provision of anti-syphilitic therapy. This is documented in correspondence which was exchanged between local officials and P.H.S. physicians from April 27 until August 11, 1942. In the first of these letters Assistant Surgeon General Vonderlehr was informed that some of the syphilitic subjects were being called for examination for induction into the Armed Forces and were rejected because of a positive serologic test for syphilis. They were then directed to undergo treatment. Vonderlehr, who 10 yr earlier had no plans for a chronic investigation, now was of the opinion that:

The present study of untreated syphilis is of great importance from a scientific standpoint. It represents one of the last opportunities which the science of medicine will have to conduct an investigation of this kind [52].

*The subjects were denied surgery at the expense of the Public Health Service. (Letter from Vonderlehr to subject [51].)

Therefore, the Macon County Selective Service Board was furnished “a list containing 256 names of men under 45 yr of age who are to be excluded from their list of draftees needing treatment” [53]. In June the Board agreed to exclude these men. Two months later it was found that:

Some of the Control cases who have developed syphilis are getting notices from the draft boards to take treatment. So far, we are keeping the known positive patients from getting treatment. Is a control case of any value to the study if he has contracted syphilis? Shall we withhold treatment from a control case who has developed syphilis? (M. Smith to Vonderlehr, [54]).

Vonderlehr responded to this inquiry by recommending that the infected control subjects should receive “appropriate treatment,” as cited before [46].

Since the minimum age for admission to the Study was 25 yr in 1932, all except the fourteen subjects who were added in 1938 must have been at least 35 yr of age at the time of this correspondence. Since men who were more than 38 yr of age ordinarily were not inducted, it is unlikely that many of the subjects would have been directed to treatment as a consequence of contact with the Selective Service Board. However, the officials who were responsible for the Study chose to prevent the loss from the Study of that portion.

The Alabama legislature in 1927 enacted a venereal disease control law which stated that:

The county health officer shall require persons infected with venereal disease to report for treatment to a reputable physician and continue treatment until such disease, in the judgement of the attending physician is no longer communicable [55].

Consequently, for the Study to be carried out in AL one of its laws had to be ignored by officials of a Federal agency, the Public Health Service. In 1942 officials of a second Federal agency, Selective Service, cooperated in the circumvention.

Despite the published acknowledgement that “a small number” of control subjects contracted syphilis during the first 5 yr of the Study [4, 45] and the unpublished comment on this matter after another 5 yr [54], the control subjects were presumed to remain non-syphilitic and, therefore, suitable for comparisons. Even without evidence to the contrary, such a supposition would be quite unlikely in a society which is known to have a high prevalence of this infectious disease. One of the investigators also informed me that some men did develop syphilis, but that since the policy had always been to treat primary syphilis, such infections did not affect the Study [56]. This assessment is not realistic either, because the clinical surveys were conducted far too infrequently for the investigators to routinely detect the primary or even the secondary lesions. Such cases would have had to be detected by serologic testing. This was said to have been carried out at each examination, but results have not been published.

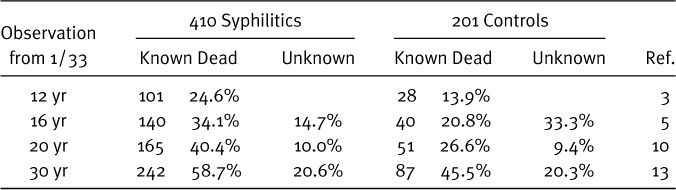

TABLE 4. Survival of Participants in Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The family status of the subjects was commented on only as it was found in the reevaluation of 1951–’52. Virtually all subjects were or had been married. A larger proportion of the subjects who had had syphilis was widowed (9.8% versus 5.8%). They had had an average of 5.2 children, of whom 57.3% were living, while the control subjects had an average of 6.3 children, of whom 70.1% were alive [8]. No information was reported as to whether the difference in the survival of wives or of children was attributable to syphilis. Indeed, it was concluded that “the syphilitic and non-syphilitic groups interviewed are quite similar according to family status” [8].

Up to about 55 yr of age the subjects who initially had syphilis exceeded the control subjects in the number of their ailments, not necessarily related to syphilis. Thereafter, symptoms of ageing supervened in both groups and differences in symptomatology diminished. On Table 4 the mortality rates of the two groups are compared from the 12th to 30th yr of the Study. The mortality rate of the diseased subjects persistently was greater, but this difference also diminished with age. The extent to which treatment of syphilis was a factor in the reduction of the disparity is uncertain.

The Tuskegee Study and the Introduction of Penicillin Therapy

The modern era of anti-syphilitic therapy began in 1943, when penicillin was first administered to patients with primary syphilis [57]. The great efficiency of penicillin in this stage of the disease was recognized at once, but reliance on it alone to treat later stages took a decade to be fully accepted. This brings us to the question whether, indeed, the syphilitic subjects are likely to have been harmed, as has been alleged, because they were not systematically given a therapeutic course of penicillin soon after this drug became available. Secondly, to what extent was the Study affected by the non-systematic administration of penicillin?

Syphilologists in the 1940s had difficulty in drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of penicillin in late syphilis for two main reasons: (1) optimal dosage schedules had to be established and this was complicated by the successful efforts to produce new preparations which are excreted more slowly. When several penicillin products became available before a dosage schedule was established for one, it took longer to gather sufficient results to evaluate any one regimen. (2) Despite the optimism that was engendered by the response to penicillin of primary syphilis, there was no rapid way to determine whether the long term effect of penicillin on tertiary forms of the disease would be superior to that of metallo-therapy. Optimal penicillin dosages to treat the various phases of syphilis had at last become standardized by 1960, the 27th yr of the Tuskegee Study, when a Public Health Service guide stated that “Arsenicals have no place in modern syphilis therapy. There is also little, if any, indication for the use of bismuth” [58].

A typical comment about the treatment of visceral lesions in 1948 was:

There is no good evidence that the rate of healing is more or less rapid following penicillin (than metallotherapy).… Sufficient evidence is at hand to show that a single course of penicillin therapy will not induce prompt healing or prevent gummatous recurrence in all patients with cutaneous and/or mucous membrane gummas [59].

The organs which are most commonly affected in advanced syphilis are the central nervous system and the proximal portion of the aorta. In an uncontrolled study published in 1948 the results of penicillin treatment of 274 patients with general paresis who were observed for at least 1 yr following the treatment showed improvement in 62% [60]. A more recent investigation of 100 patients with central nervous system syphilis who were observed for an average of 21 yr after treatment failed to show superiority of penicillin therapy. Seventeen per cent of 36 patients who had received treatment other than penicillin, 56% of 34 patients who had received both penicillin and other treatment, and 20% of 30 patients who had been treated with penicillin alone suffered progressive deterioration of the nervous system. Of those who received penicillin, irrespective of the dosage, 39% were at least partial treatment failures [61].

Syphilitic involvement of the heart or aorta can not be diagnosed until an anatomic deformity of the aortic valve or adjacent structures has occurred. On the average, this takes place in about 10% of persons with untreated syphilis and begins 15–20 yr after the primary infection. By then the fundamental structural damage has taken place and further deterioration results from abnormalities of the heart action and blood flow, irrespective of the presence of absence of the pathogen [62]. At the time the subjects entered the Tuskegee Study they had had syphilis for from 3 to more than 30 yr. Thus, the 70 subjects who were examined in 1948 already had been diseased for at least 18 yr. At that examination 10% of the syphilitic and 2.4% of the control subjects had findings which could have been due to syphilitic cardiovascular disease [5]. The medical literature gave little impetus to the initiation of penicillin therapy in this circumstance. According to C. K. Friedberg in 1949: “The dosage of penicillin has not yet been standardized and its usefulness in cardiovascular syphilis cannot be properly evaluated until many years have elapsed” [63]. At last examination, in 1969, 2 of 76 syphilitic and 2 of 51 control subjects had findings consistent with those of cardiovascular syphilis [40].

Aside from the episode in 1942 when exemption from pre-military examinations was obtained for a minority of the subjects, the repeated assertion of the investigators that no efforts were made to prevent them from obtaining treatment probably was accurate. This might have been treatment specifically for syphilis, or since the advent of penicillin, also treatment for other infections which could incidentally have been anti-syphilitic. Of 160 diseased men who were examined in the 20th yr of the Study 64.0% had received some anti-syphilitic therapy. 27.5% of these 160, and 32.6% of 105 control subjects had received penicillin. Only 7.5% of the originally syphilitic subjects were considered to have received adequate treatment, all with penicillin [10]. At the 30 yr mark 96% of the 90 subjects who were examined had been treated, and treatment was considered “probably adequate” in 22% [13].

Aftermath and Analysis

On Nov. 16, 1972, 4 months after the Tuskegee Study began to become notorious, C. Weinberger, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, officially terminated it. Eight months after this a class action suit against the Public Health Service and some of the individual investigators was filed. Indemnity of 3 million dollars per participant was asked because of deaths, mental and physical suffering, and abnormalities in children of subjects due to congenital syphilis [15].

Let us look at the probability of survival to the time of the suit. At the inception of the Study 44% of the subjects were 25–39 yr of age and 56% were between the ages of 40–78 yr [2, 2a]. The life expectancy of a non-syphilitic Negro male in the Study area was such in 1933 that someone who was 30 yr old could expect to live until 1971, and if he were 50 yr of age in 1933 he could anticipate living until 1954 [7, 64]. The survivors who were examined in 1968 had a mean age of 69 yr and a maximum of 91 yr [40]. Consequently, virtually all subjects who were alive in 1973 had outlived the life expectancy of their non-syphilitic peers!

A tentative out-of-court settlement of the suit was reached on Dec. 13, 1974 and this was finalized with minor modifications on Sept. 18, 1975. It was agreed that U.S.A. would pay $37,500 to each surviving participant who initially had syphilis and $15,000 to each surviving control subject. The estate of a “syphilitic” who died before July 23, 1973, the date the suit was filed, shall receive $16,000 and the estate of control subjects who died before that date shall receive $5000. The sum to be paid to 36 “syphilitics” and to 8 “controls” who could not be located at the time of the adjudication or to their estates, shall depend on documentation whether or not they were living on July 23, 1973 [65].

Now that most of the principal facts have been presented, how does the Study stand up against the general principles of research which were outlined at the beginning?

(1) I believe that knowledge of the natural course of syphilis was sufficiently uncertain in 1930 and therapeutic problems were great enough that the undertaking of such an investigation was justified. The reports of the Cooperating Clinical Group [47–49] did not diminish the justification.

(2) We do not know to which specific questions answers were to be sought, either at the outset of the Study or at the uncertain time when it became longitudinal, because no protocol ever was published or alluded to. If, indeed, no comprehensive plan existed the probability that the quality of the information that would be obtained would justify the risks and expenses diminished greatly. We do know that two unknowns were being compared throughout the investigation: a diseased group which received uncertain amounts of treatment, and an originally unaffected group in whom the development of the disease under investigation was not adequately documented. While the investigators have been roundly criticized for having withheld treatment, their results were in part obscured by the fact that access to treatment was not restricted. From the available data we can only infer that many questions were not posed in a way whereby the maximum amount of information could be gathered.

(3) The limitation of the investigative subjects to Black men did not of itself diminish the potential general value of the data very much. Only syphilitic involvement of the central nervous system occurs less frequently in this racial group than in a Caucasian population, and one may therefore expect that a somewhat deficient amount of information about this group of manifestations could have been collected.

(4) The most glaring gap in the data is the lack of any investigation of the effect of syphilis on the family. What was the serologic status of the wives and children? How prevalent were signs of congenital syphilis? Blood could easily have been obtained to test for paternity at the time it was obtained to test for syphilis. What were the results of the serologic tests of the control subjects over the years? Other opportunities were missed as well. Since a group of inadequately treated syphilitic men was selected in the beginning, their course could profitably have been compared with that of the supposedly untreated subjects, the studies of the Cooperating Clinical Group not withstanding. The importance of some of the questions which were dominant in 1930 diminished when the much safer and more efficient penicillin therapy became available. However, a new question could have been considered: What effect does penicillin have on late syphilis? This could have been addressed by randomly selecting a portion of the subjects and administering a presumably therapeutic course of penicillin to them, the others remaining as controls. It is unknown whether ethical, fiscal or other considerations prevented this course of action.

(5) Since the clinical ramifications of a disease are studied most efficiently in the environment in which it is prevalent, and the environment in this sense is both geographic and socio-economic, the site of the Study was appropriate. In view of the grossly inadequate budget of the Venereal Diseases Division of the P.H.S. during the early years of the Study one may question whether an investigation of this magnitude should have been attempted. It seems plausible that some aspects of the Tuskegee Study would have been improved by more adequate funding. The mean annual budget of the Venereal Diseases Division during the decade 1946–1955 had increased to $12,187,000 [41], and therefore the possibility for more adequate funding of the Study came to exist. Unfortunately, it is impossible to estimate how significant the improvements might have been since we lack knowledge of what procedural deficiencies the investigators recognized and considered remediable.

(6) Finally, was enough attention devoted to the hazards of the subjects? Criticisms of the lack of their informed consent are anachronistic, since this topic only began to receive much discussion following publication of the code for permissible medical experiments by the tribunal of the Nuremberg war crimes trial, some 16 yr after the Study had begun [22]. The P.H.S. did not adopt a policy definition of informed consent until 1966 [66]. The very critical report of the Advisory Panel which analyzed the Tuskegee Study referred to the cooperation of the local Selective Service Board with the Study director to exempt subjects from military conscription and thereby from one route to compulsory anti-syphilitic therapy [67]. Surprisingly, this report did not even mention the AL venereal disease control act. Because of their relatively high ages few subjects would have been lost from the Study had the Selective service procedure not been interfered with. In 1941 serologic evidence of syphilis was detected in 22.7% of the Black AL military recruits, a figure that is remarkably similar to the 26.5% found 10 yr earlier in the somewhat older Macon County population [68]. However, evidence that the Venereal Disease Control Act was having little impact can not be considered as justification to disregard it.

Virtually everyone would agree that it is unethical to withhold unequivocally efficaceous treatment from patients who have a potentially fatal disease. One problem with which we have been struggling is whether the investigators absolved themselves from this conflict by restricting participation in their investigation to persons who were in a phase of the disease in which the treatment was much less efficaceous than when it is administered soon after the onset. The available treatment might have exerted a definitely beneficial effect on the prognosis of only 12.5% of the subjects [33]. While this is not negligible, it is the reason why I have emphasized the breach of law (legal ethics) over the breach of medical ethics, both as revealed in the conception of the investigation and in the negotiations with the Selective Service Board.

Conclusion

The importance to the practice of medicine of learning the natural history of diseases had been propounded for a century when the Tuskegee Study of the natural history of syphilis was undertaken. However, methodology for efficient clinical investigation which took into account ethical concomitants which are now important had not been developed. The Tuskegee Study had been in progress for 12 yr when the possibility of a dramatic improvement of treatment appeared, for 16 yr when new insights into the ethical implications of research began to be advocated, and was 39 yr old when it abruptly became the subject of severe criticism for ethical deficiencies. The author’s thesis has been that ethical and methodological attributes must be evaluated separately first and the consequences of their interactions thereafter. In reference to a chronic investigation changes in ethics and in methodology must be viewed in their historical contexts. The righteousness of the ethical critics fails to take into account that in the context of the 1930s thoughtful physicians could detect no ethical dilemma in an investigation such as the Tuskegee Study, and also refuses to accept the evidence that very little would have been accomplished therapeutically by initiating penicillin treatment in the 1950s. Actually, if the investigators did perceive an ethical problem when they began their investigation, the results of the treatment of late syphilis which were reported during the first decade of the Study could have reassured them (e.g. [48, 49]).

At the other extreme from the criticism of ethics, Gjestland, in the monograph in which he reevaluated the data of Boeck and Bruusgaard, commented that “there is little doubt that the ‘Alabama Study’ is the best controlled experiment ever undertaken in this particular field” [69]. Since the Tuskegee Study was initiated without a comprehensive plan, this view is difficult to support. What is most regrettable is that, while ethical problems may have been historically unavoidable, methodologic defects, many of which were probably surmountable, precluded as much knowledge from being obtained as the participants could have made available.

As it turned out, Vonderlehr was correct when he wrote in 1942 that “The present study of untreated syphilis … represents one of the last opportunities which the science of medicine will have to conduct an investigation of this kind” [52]. In 1970 W. J. Brown, a successor as chief of venereal disease control in the P.H.S., used almost the same words, changing only the tense:

Since today it is both undesirable and impossible to study the effects of untreated syphilis on a large and homogeneous population group, the Boeck-Bruusgaard and Tuskegee studies are possibly the best information on the long-term course of untreated syphilis we shall ever have [70].

For this reason, as well as in compensation for the participation of more than 600 citizens of Macon County, AL the Tuskegee Study deserves to be fully documented in a monograph which is based on all of the data which are in the files of the Public Health Service.

REFERENCES

1. Heller J: Syphilis victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 yr. New York Times pp. 1, 8. July 26, 1972.

2. Vonderlehr RA, Clark T, Wenger OC et al.: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Ven Dis Inform 17:260–265, 1936.

2a. Same as 2, plus discussion: JAMA 107:856–860, 1936.

3. Heller JR, Bruyere PT: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. II. Mortality during 12 yr of observation. J Ven Dis Inform 27:34–38, 1946.

4. Deibert AV, Bruyere MD: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro—3. Evidence of cardiovascular abnormalities and other forms of morbidity. J Ven Dis Inform 27:301–314, 1946.

5. Pesare PJ, Bauer TJ, Gleeson GA: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Observation of abnormalities over 16 yr. Am J Syph 34:201–213, 1950.

6. Rivers E, Schuman SH, Simpson L et al.: Twenty yr of follow-up experience in a long-range medical study. Publ Hlth Rep 68:391–395, 1953.

7. Shafer JK, Usilton LJ, Gleeson GA: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: Prospective study of effect on life expectancy. Publ Hlth Rep, 684–690, 1954.

8. Olansky S, Simpson L, Schuman SH: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: Environmental factors in the Tuskegee Study. Publ Hlth Rep 69:691–698, 1954.

9. Peters JJ, Peers JH, Olansky S et al.: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: Pathologic findings in syphilitic and non-syphilitic patients. J Chron Dis 1:127–148, 1955.

10. Schuman SH, Olansky S, Rivers E et al.: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: Background and current status of patients in the Tuskegee Study. J Chron Dis 2:543–558, 1955.

11. Olansky S, Cutler JC, Price EV: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. Twenty-two yr of serologic observation in a selected syphilis study group. Archs Dermat 73:516–522, 1956.

12. Olansky S, Schuman SH, Peters JJ et al.: Untreated syphilis in the male Negro. X. Twenty yr of clinical observation of untreated syphilitic and presumably nonsyphilitic groups. J Chron Dis 4:177–185, 1956.

13. Rockwell DH, Yobs AR, Moore MB: The Tuskegee Study of untreated syphilis. The 30th year of observation. Archs Int Med 114:792–798, 1964.

14. Anonymous: A matter of morality. Time, p. 54. Aug 7, 1972.

15. Anonymous: Black victims of syphilis experiment file class action suit for $1.8 billion. Equal Justice (publication of NAACP), 3:2, 1972.

16. Anonymous: Weighing Medicine’s need to know against the individual’s rights and safety in ‘human experimentation.’ Med Wld News 37, Passim. June 8, 1973.

17. Louis PCA: Essay on Clinical Instruction. Trans. by P. Martin. London: S Highley 1834, p. 27. (Original publication, Paris 1831).

18. Cheever DW: The value and the fallacy of statistics in the observation of disease. Boston: D Clapp, 1861, pp. 415. Also in Boston Med Surg J, 63, 1861.

19. Hill AB: Medical ethics and controlled trials. Brit Med J 1:1043–1049, 1963.

20. Bleuler E: Das autistisch-undisziplinierte Denken in der Medizin und seine Überwindung. 3rd edition Berlin: J Springer, 72–82, 1922.

21. Anonymous: Supplementary report of the Judicial Council, Am Med Ass JAMA 132:1090, 1946.

22. Nuremberg Military Tribunals: Trials of war criminals (The medical case). US Gov Printing Office 2:181–184, 1974. Reprinted in Shimkin MB: The problem of experimentation on human beings—I. The research worker’s point of view. Science NY 117:205–207, 1953.

23. Ivy AC: The history and ethics of the use of human subjects in medical experiments. Science NY 108:1–5, 1948.

24. Hill AB: The clinical trial. Brit Med Bull 7:278–282, 1951.

25. Bruusgaard JE: Über das Schicksal der nicht spezifisch behandelten Luetiker. Archs f Dermat u Syph 157:309–322, 1929.

26. Sowder WT: An interpretation of Bruusgaard’s paper on the fate of untreated syphilitics. Am J Syph 24:684–691, 1940.

27. Turner TB: The race and sex distribution of the lesions of syphilis in 10,000 cases. Bull J Hopkins Hosp 46:159–184, 1930.

28. Ehrlich P. Ueber die Behandlung der Syphilis mit Dioxydiamido arsenobenzol. Klin-ther Wchnschr Berlin 17:1005–1018, 1910.

29. Sazerac R, Levaditi C: Emploi du bismuth dans la prophylaxie de la syphilis. Comp rendu Acad Sci Paris 174:128–131, 1922.

30. Wright CS: Mercury in the treatment of syphilis. Am J Syph 20:660–680, 1936.

31. Moore JE, Kemp JE: The treatment of early syphilis—2. Clinical results in 402 patients. Bull J Hopkins Hosp 39:16–35, 1926.

32. Stokes JH: Some problems in the control of syphilis as a disease. Am J Syph 23:549–576, 1939.

33. Diseker TH, Clark EG, Moore JE: Long-term results in the treatment of latent syphilis. Am J Syph 28:1–26, 1944.

34. Pugh JH, Stokes JH, Brown LA et al.: A study based on personal follow-up results in a syphilis clinic of the patient’s reasons for lapse of treatment. Am J Syph 14:438–450, 1930.

35. Cole HN, DeWolf H, McCluskey JM et al.: Toxic effects following use of arsphenamines. JAMA 97:897–904, 1931.

36. Clark T: The control of syphilis in southern rural areas p. 44 Chicago: Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1932.

37.Op cit No. 36, pp. 27–35.

38.Op cit No. 36, pp. 17–19.

39. Letter from Vonderlehr RA to Deibert AV, Dec. 5, 1938.

40. Caldwell JG, Price EV, Schroeter AL et al.: Aortic regurgitation in the Tuskegee Study of untreated syphilis. J Chron Dis 26:187–194, 1973.

41. Anderson OW: Syphilis and society. Problems of control in the United States 1912–1964. Chicago: Hlth Inf Fdn, Res Ser 22, 6, 53, 1965.

42. Letter from Isaacs L (Treasurer, Milbank Memorial Fund) to Vonderlehr RA, Apr 23, 1940.

43. Letter from Brown WJ to Robertson A (Executive Director, Milbank Memorial Fund), Aug 18, 1965.

44. Letter from Deibert AV to Vonderlehr RA, Nov. 7, 1938.

45. Letter from Deibert AV to Smith M, Aug 22, 1942.

46. Letter from Vonderlehr RA to Smith M, Aug 11, 1942.

47. Stokes JH, Usilton LJ, Cole HN et al.: What treatment in early syphilis accomplishes. Am J Med Sci 188:660–684, 1934.

48. Padget P: Long-term results in the treatment of early syphilis. Am J Syph 24:692–731, 1940.

49. Usilton LJ, Miner JR: A tentative death curve for acquired syphilis in white and colored males in the United States. J Ven Dis Inf 18:231–239, 1937.

50. Butler BN, Chairman, Tuskegee Syphilis Study ad hoc Advisory Panel: Final Report. US Dep’t of HEW, PHS, (a) p. 14; (b) p. 29, Apr 28, 1973.

51. Letter from Vonderlehr RA to subject of Tuskegee Study, Apr 11, 1941.

52. Letter from Vonderlehr RA to Smith M, Apr 30, 1942.

53. Letter from Smith M to Vonderlehr RA, June 8, 1942.

54. Letter from Smith M to Vonderlehr RA, Aug 6, 1942.

55.General laws of the legislature of Alabama. Session of 1927. Montgomery: Brown p. 716, 1927.

56. Olansky S: Personal communication, Nov. 19, 1973.

57. Mahoney JF, Arnold RC, Harris A: Penicillin treatment of early syphilis: a preliminary report. Am J Publ Hlth 33:1387–1391, 1943.

58. Publ Hlth Ser Publ No. 743: Syphilis. Modern diagnosis and management. Washington: US Gov Printing Office, p. 12, 1960.

59. Tucker HA: Penicillin in benign late and visceral syphilis. Am J Med 5:702–708, 1948.

60. Kopp I, Rose AS, Solomon HC: The treatment of late symptomatic neurosyphilis at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital. Am J Syph 32:509–520, 1948.

61. Wilner E, Brody JA: Prognosis of general paresis after treatment. Lancet 2:1370–1371, 1968.

62. Webster B, Rich C, Densen PM et al.: Studies in cardiovascular syphilis. III. The natural history of syphilitic aortic insufficiency. Am Heart J 46:117–145, 1953.

63. Friedberg CK: Diseases of the Heart. Philadelphia: W B Saunders Co, p. 830, 1949.

64. Linder FE, Grove RD: Vital statistics in the U.S.A. 1900–1940. Washington: Gov Printing Office p. 150, 1943.

65. USDC, Mid Dist AL, Civil Action No 4126-N, Sept 18, 1975.

66. Epstein LC, Lasagna L: Obtaining informed consent. Archs Int Med 123:682–688, 1969.

67.Op cit No. 50, pp. 9–10.

68. Vonderlehr RA, Usilton LJ: Syphilis among men of draft age in the U.S.A. JAMA 120:1369–1371, 1942.

69. Gjestland T: The Oslo study of untreated syphilis. Acta Derm-Ven, 35, suppl 34, p. 31, 1955.

70. Brown WJ, Donohue JF, Axnick NW et al.: Syphilis and other venereal diseases. Cambridge: Harvard Univ Press, pp. 20–21, 1970.