Venereal Disease Control by Health Departments in the Past

Lessons for the Present

Introduction

As one reviews the history of public and professional responses to epidemic diseases before and after and discovery of effective methods of control, one realizes that the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) problem, while obviously new, has many parallels in the past. Throughout history civilization has been confronted with pandemics such as influenza, smallpox, plague, cholera, syphilis, and others, but only within the past century have there been specifics to deal with them. Even in recent history, we have experienced problems similar to AIDS, notably the spread of venereal disease (VD) during World Wars I and II. Thus patterns of programs for VD control developed during the past have relevance now.

Whatever approach may be taken in dealing with the AIDS problem, it must be, as learned from past experiences, both non-judgmental and non-moralistic if it is to be effective. There may be a classic parallel in our World War I and WWII handling of the problems associated with the explosive spread of venereal diseases in both the military and civilian populations and the resultant obstructions to the war effort. Because of the wartime needs in both the military and civilian populations, it was obvious and accepted that the problem had to be approached from a medical point of view rather than avoided because of value judgments. At that time, diagnostic and treatment procedures for syphilis and gonorrhea were complex, time-consuming, expensive, heavily dependent upon individual initiatives, and “primitive” according to today’s advances. However, the “public health” approach to control, utilizing existing knowledge and resources, proved to be highly effective in lowering incidence and prevalence rates.

Dr. John C. Cutler is emeritus professor of international health at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health. He was one of the Public Health Service physicians involved in the study. Dr. R. C. Arnold is a retired assistant surgeon general in the Public Health Service who worked on research on treatment of syphilis with penicillin.

Originally published in the American Journal of Public Health 78 (1988): 372–76.

Reprinted by permission of the American Public Health Association.

It should be noted with respect to AIDS that pathogenic agents evolve or mutate, and that resultant new challenges to the health community constantly appear. This may be illustrated by the pandemic of influenza of World War I, by frequent emergence of new strains of viruses and bacteriae, the development of chemotherapeutic and antibiotic resistance, as with the gonococcus. Such recurrent events calls for control efforts based upon earlier experience, existing knowledge about the agents, and evolution of new or modified control measures. In addition, there are continuing changes in the risk of disease transmission within various geographic, social, and age groups because of the changing patterns of transportation, food movement, travel and, in particular, changes in social behavior such as age at onset and patterns of sexual activity, patterns of marriage and break-up, public reaction to sexual behavior, etc. Over the decades, the public health sector has been able to respond to the impact of these various factors. Within the United States, continuing and/or evolving patterns of disease and disability, life expectancy, etc., reflect the successes and failures, as well as the constantly changing challenges to the health of the community.

A review of the response of all levels of government to the problem of syphilis might be useful in charting a course for control of AIDS today. There are remarkable parallels between the two diseases, including a long latency period before the disabling or fatal clinical symptoms become manifest. The challenges posed by syphilis to the medical/public health professions in developing patterns of cooperation in educational and research programs and in methods for securing and implementing effective public and professional involvement in the VD control effort, clearly have relevance to the problems posed today by AIDS.

The Impact of World War I

At the outset of World War I, when VD was a leading cause of incapacitation or rejection for active duty, public concern was sufficient to override the previous moralistic judgmental inhibitions against VD control efforts. In retrospect, these earlier attitudes seem once again to complicate a rational approach to the problems of the present AIDS epidemic. Because of the overriding concerns with the war effort it was possible under the leadership of the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) in 1917 to initiate a cooperative control program among state and local health departments and the private sector, including medical practitioners, the hospital system, and voluntary agencies. It was viewed by the public as necessary, in support of the war effort, to keep the military fit for duty rather than restricted or incapacitated by syphilis and gonorrhea and the scheduling requirements of existing treatment regimens. The essential elements of the WWIVD control effort included case reporting, widespread availability of testing (using the relatively costly and varied procedures then available), the provision of arsphenamine (for treatment of syphilis) at public expense, promotion of prophylaxis— both chemical and use of condoms by the military, in particular—establishment of treatment facilities, and a public education program, all basically centered in the state health departments.

Within a year, the seriousness of the problem was sufficiently appreciated to result in enactment of the Chamberlain-Kahn Act in 1918 which established a formal basis for cooperative efforts within the federal government—specifically between the USPHS and the Army and Navy. In addition, the legislation provided for a VD Division within the Public Health Service, authorized grants to states for VD control programs, and provided specifically for VD research. The law was written so as to promote the establishment and implementation of minimum standards of program efficiency by the grantees. Because of the perceived significance of such a cooperative and interdependent control program in promoting the war effort, the program enjoyed wide public acceptance as long as the wartime conditions prevailed. This has been documented in fascinating detail by Brandt.1

With the winning of the war, the attitudes toward VD control changed. In light of the present public attitudes, a quotation from Vonderlehr and Heller2 is most relevant for it mirrors the importance of public and professional attitudes and the resultant government programs:

A change in the attitude of the people was observed with the return of the troops after World War I. This change was reflected in Congress. Once the Versailles Treaty was signed the people of the United States assumed that the Germans had been beaten for all time. When the U.S. Army was demobilized a similar assumption was made regarding the defeat of the spirochete and the gonococcus, and the VD problem was forgotten. In the third year of existence of the new Division of Venereal Diseases, the grant-in-aid program dwindled to $100,000 and thereafter was discontinued altogether. The activities of the Public Health Service in venereal disease control were reduced to research investigations. Venereal disease control was in the doldrums and remained there for about fifteen years.

An incident which portrays the prudish attitude once taken by the public and even by the medical profession toward the venereal diseases, occurred during the early experiences of one of our preeminent specialists. Thirty years ago, Dr. P. S. Pelouze read his first scientific paper on gonorrhea before a meeting of physicians. One of them rushed up to Dr. Pelouze and said: “Pelouze, you are making a grave mistake in letting yourself become known as one interested in gonorrhea; it will ruin you.”

Dr. Pelouze replied, “Do you mean that a doctor who shows an interest in a disease that afflicts millions of human beings and has been so badly neglected by our profession that our lack of knowledge upon it is our greatest medical blot, will be ruined?”

The physician replied, “Most assuredly.”

“Don’t you think, then,” said Dr. Pelouze, “that it is time a few of us were ruined?”

Most physicians felt as Dr. Pelouze’s colleague, and they reflected the attitude of the public generally. Most people would rather not have their family doctor, or a doctor related to them, associated with venereal disease.2

Renewed Interest in VD Control

By the mid-1930s the seriousness of the VD problem was beginning to come back in to the medical and public consciousness, primarily because of the leadership of Dr. Thomas Parran who became Surgeon General of the USPHS in 1936, a year in which the USPHS budget for VD control was $58,000. By then the serious problems of disability, death rates, and costs of long-term effects of syphilis alone were again evident nationwide. A gradual, well-planned move to reestablish a full-fledged national VD control program began. It is relevant to remind ourselves that the problems Dr. Parran faced then are sharply mirrored in the current public and professional attitudes about AIDS. For instance, because of the planned use of the word “syphilis” in a radio program to be broadcast nationally, the Surgeon General of the USPHS was denied permission to air a program. However, shortly after this episode, the Reader’s Digest was concerned and farsighted enough to publish an article entitled “Why Don’t We Stamp Out Syphilis?” which focused national attention on the extent of the problem. There was a highly supportive public response, matched by strong support from the medical and public health communities which were aware of the problem but had been unable to move effectively because of the lack of adequate financial and political support. It should be noted also, as is evident today, that in the period before the resurgence of public interest and availability of governmental funds for research and program implementation, the medical and public health schools and the voluntary agencies had been carrying out basic and clinical research on syphilis and gonorrhea as well as public health control studies. Support for such work came primarily from voluntary agencies, such as the Milbank Memorial Fund, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Rosenwald Foundation, the Reynolds Foundation, and others, showing their recognition of the significance of the problem and the need for action. As is often the case, this private sector interest paved the way for later governmental action. Much had been learned from these pioneering projects, but nationwide, applications of the knowledge that had been acquired could come only when there was widespread and active public support to provide the funding required.

As a result of the growing public concern and interest, a national conference was called by Surgeon General Parran in December 1936, which put forward plans for a revitalized national VDL control program. The VD control program was restarted the same fiscal year when funds became available through Title VI of the Social Security Act. This is best summarized by a quote from the History of the USPHS.3

The Social Security Act of 1935 marked the beginning of an important public health era in the United States. Included in the Act was Title VI which authorized general health grants to States by the Public Health Service. . . .

Under Title VI of the Social Security Act the Public Health Service was authorized to allot $8,000,000 annually in grants-in-aid to State health departments. The appropriation of $2,000,000 annually for scientific research was also authorized. The law further provided that the distribution of funds to the States should be based proportionately upon population, financial need, and the existence of special health problems. These funds were not given without what may legally be termed a consideration, as the States were required to match dollar for dollar the sums appropriated for general health services and special health problems. A part of the grant-in-aid appropriation was reserved for the training of State and local health personnel. Funds allotted for training, however, did not have to be matched. Regulations for the administration of grants-in-aid funds under Title VI of the Social Security Act were promulgated by the Public Health Service after conference with the State and Territorial health authorities. Funds authorized by the Social Security Act first became available on February 1, 1936, when Congress appropriated $3,333,000 for the remaining five months of that fiscal year.

Thus, for the first time in the history of the United States, the Federal government entered into a partnership with the States and Territories for the protection and promotion of the health of the people. For the first time the Public Health Service was under legal authority cast in the role which it had so long wished to play, that of partner, adviser, and practical assistant to the State health departments, and through them to municipal and local health services to be accomplished with Federal aid, and to leave the administration of these activities to the States. Consultant and technical services have been provided for the States in the planning of both general and specific programs. Personnel of the Public Health Service frequently have been assigned to the States upon request to administer health programs.

In 1938 the Lafayette-Bulwinkle Act, approved May 24, implemented the attack upon syphilis and gonorrhea through grants-in-aid to the States and expansion of research specifically upon these diseases by the Public Health Service. In 1939 amendments to the Social Security act raised the ceiling of grants-in-aid to the States under Title VI to $11,000,000, with provision that the increases should be utilized in the States for special health problems. The National Health Conference in 1938, in which the Public Health Service participated, proposed not only an expansion of public health services but also the construction of hospitals and studies of methods, needs, and resources of public medical care for the indigent.3

The program, inaugurated by Dr. Parran, was based upon the nine basic principles of public health control of syphilis which he had formulated:

• A trained public-health staff;

• Case finding and case holding;

• Premarital and prenatal serodiagnostic testing;

• Diagnostic services available;

• Treatment facilities available;

• Distribution of drugs for treatment;

• Routine serodiagnostic testing;

• A scientific information program;

• Public education.

It should be noted that concurrent with the public health concerns about syphilis and the resultant political and public health program responses there had been a highly active and productive research program carried out both nationally through cooperative efforts within the university community and the USPHS and, internationally, through the Health Organization of the League of Nations. Through these efforts, new arsenical preparations were developed and treatment programs worked out which cut treatment time from the previous 18–24 months to as few as five days. All of these new treatment procedures had a high rate of toxic reactions, and rare fatalities, but they were accepted realistically then in light of the long-term effects of the untreated disease and the accompanying social and economic costs.

In spite of treatment modalities that were complex and toxic by today’s standards, the well-planned and coordinated national program made real headway. Through cooperative programs made possible by increased funding from both federal, state, and local government, a massive national VD control program was mounted thanks to the Social Security Act of 1935 and the leadership of the national public health community.

World War II and After

With the beginning of World War II, the need for large scale application of the shortened, intensive arsenical-based treatments requiring up to 10 weeks in hospitals was recognized: the increased patient mobility in civilian as well as military populations due to wartime needs caused problems in completing therapy. Starting in 1942, so-called Rapid Treatment Centers (RTCS) were begun and by 1946 had been established in 35 states and the District of Columbia, most of them under state health department management but with federal financial support and strong professional cooperation. By 1946 the USPHS had been given congressional responsibility for national administration of the program; $5 million was appropriated to subsidize the centers and to pay the local general hospitals which were also important resources for treatment—usually local-government administered. A total of 59 projects in 37 states—50 state or locally operated and nine projects USPHS operated—were in existence. In 1945, of the 183,000 cases of syphilis reported nation-wide, 52,000 (29 per cent) were treated in the RTCS.

The entry of the us into WWII had served as a catalyst to the national program, again because of the high rates of rejection of draftees due to syphilis and because of the high rates of absence from duty of military manpower resulting from syphilis and gonorrhea. As in WWI, cooperative agreements were set up between the USPHS and the military. In the same fashion, working through the Conference of State and Territorial Health Officers, plans were made for the nationwide program to protect the national well-being and health. In so doing, the classic approach was taken: case finding through screening of hospital admissions, etc. The system of contact interviewing and tracing was developed, utilizing well-trained personnel, designated as VD investigators or epidemiologists. This represented a break with past tradition that had held that only a professional such as a physician, nurse, or social worker could interview and do contact tracing. In addition, the significance of the voluntary organization in the total public health program was fully recognized, and the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA), now called American Social Health Association, played a very important role in community program operations, education, and building community support.

The importance of the federal-state cooperative effort was fully recognized and further implemented through the assignment of USPHS personnel to state and local health departments so as to assure the availability of necessary professional staff. The significance of and need for research was also recognized and resulted in increased federal support of a number of highly productive academic centers as well as several existing USPHS centers. One of the latter, the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) at the Marine Hospital at Staten Island, NY had the clinical resources of the large population of merchant seamen. Here, Mahoney, Arnold, and Harris had made the discovery of penicillin therapy for syphilis and developed the VDRL test for syphilis.4

It was understood that research was of no value unless its findings could be put to use, so that with federal VD funds a number of university programs were supported which not only conducted basic and applied research but also provided training for the physicians, nurses, laboratory personnel, and administrators needed at the various levels of control programs. At the same time, within the USPHS, there was a highly productive ongoing program that assigned commissioned officers to universities for advanced training in VD control, research, etc.

World War II brought about national recognition of the adverse effects of VD, particularly syphilis, and permitted the plans that leaders such as Parran and others had developed to be realized. Public antipathy to the VD patient and to control programs was dissipated to a large extent and the health professional, financial, and administrative resources needed to establish an effective national program were made available. This is best summarized by a quote from the Military History of World War II which epitomizes the complexity and the interdependence of the public health program for the control of a disease.5

The relationship between the us Public Health Service and the Army from 1940 to 1945 was highly satisfactory and mutually advantageous. To a varying extent, every activity of the Venereal Disease Control Division of the Public Health Service during World War II affected the Army’s program. Only the history of that division’s activities (in the files of the us Public Service) can tell the complete story of that collaboration and assistance. The success of the Army venereal disease control program in the Zone of Interior was due in no small measure to the active support and cooperation provided by the Public Health Service. The program of the Public Health Service constituted one of the most valuable contributions to venereal disease control during World War II. Important phases of this program were liaison activities at service command headquarters; cooperation in the contact and separation programs; support of State and local control programs by allocation of funds and assignments of personnel; distribution of educational literature, films, and posters; analysis of statistical data; support of legislation; establishment of rapid treatment centers; organization of public meetings; and extensive research activities.5

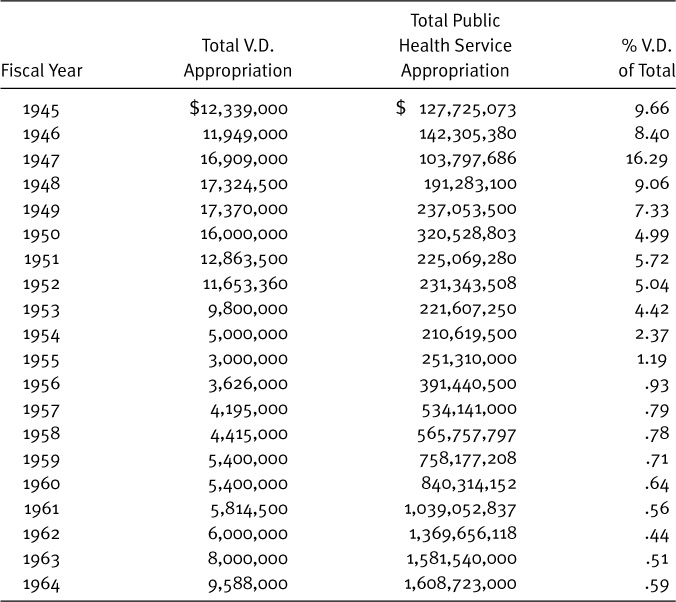

Paradoxically, the aftermath of the successes of WWII and the advances in penicillin therapy which permitted a single-injection cure of syphilis as well as of gonorrhea was the loss of both public concern about and medical and political interest in VD. The feeling in Congress was that since there existed a “single-shot” cure for syphilis there was no longer any need for the support of the full-scale public health approach which had been so successful. Appropriations for VD control were cut sharply (Table 1).6

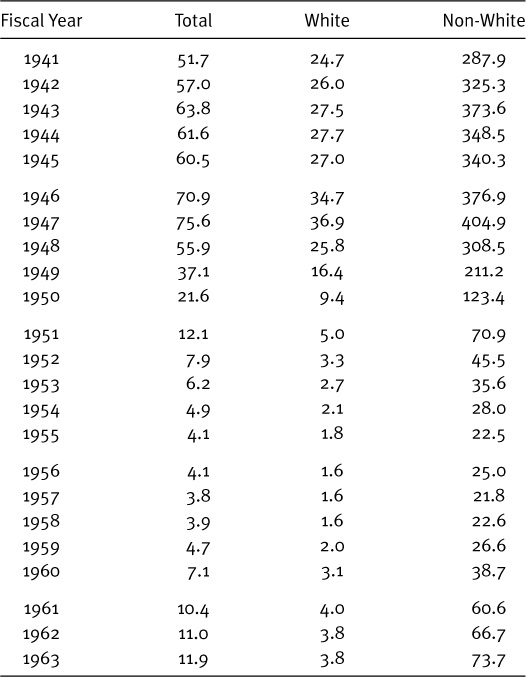

The authors have a very personal reaction to these budgetary cuts. For we well remember that during the 1955 budget hearings the Director of the USPHS VD Division, who was requesting funding so as to make further advances, was asked, “Doctor, why do you need all this money; haven’t you heard that it is now possible to cure syphilis with a single shot of penicillin?” This comment was the result of a report from the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory of the USPHS widely quoted in the press just before the hearings which showed the effectiveness of a single injection with long-acting penicillin. In spite of the subsequent explanations and discussions, Congress took the approach that the total control program was no longer needed. Starting in 1958, the budget cuts were reflected in the rise in rates of reported syphilis resulting from the fact that at state and local levels the VD control programs were forced to curtail the comprehensive approach (Tables 1 and 2).6

TABLE 1. Federal Appropriations for Venereal Disease Control, 1945–64, and VD Appropriations as a Percent of Total Public Health Service Appropriations

Sources: V.D. Appropriations obtained from the Venereal Disease Branch, Communicable Disease Center, U.S. Public Health Service. Public Health Service Appropriations obtained from U.S. Public Health Service. Background material concerning the Mission and Organization of the Public Health Service, prepared for the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, House of Representatives, April, 1963. Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office, 1963.

TABLE 2. Civilian Case Rates per 100,000 Population for Primary and Secondary Syphilis by Race, United States Summary (known military cases excluded), Fiscal Years 1941–63

Source: U.S. Public Health Service. V.D. Statistical Letter Supplement: Trends in Morbidity and Epidemiological Activity, December 1963. Table 1b.

Conclusion

The levels of public and professional interest in and support of the VD control activities at all levels of government are mirrored in federal, state, and local budgets, university training and research activities, public attitudes toward VD education and control programs promoting prophylaxis and condom usage. Thus the present public and health-community reaction to AIDS reproduces a pattern which has been well demonstrated in the past: increased federal funding in support of research and treatment, promotion of self-protective sexual behavior and practices such as condom usage and discrimination in patterns of sexual behavior, and the attempt by public health professionals to approach the problem as one of health and related economic costs, rather than to assume a judgmental, moralistic attitude. In light of past experience with syphilis and successes even before the advent of simple penicillin therapy, this approach to AIDS management, if implemented, may be expected to slow the spread of the disease. Eventually, as such an approach is strengthened and modified, as more is learned about cause and therapy, it can be expected to begin to bring the disease under control. We use the word “control” guardedly. For it is to be noted that even with simple curative therapy for syphilis and gonorrhea, the rates have fluctuated greatly, reflecting public attitudes and resultant control program changes. In the light of past experience, “control” not eradication, is the most that can be expected. The public health approach must be modified to integrate new discoveries in diagnosis, treatment, and prophylaxis as they are made, but must once again be developed to deal with the current judgmental and even panic-like reactions of the public and some health professionals to the patient needing care or the individual at risk of infection. In so doing, it must be recognized that involvement of all levels of government, the community at large, and the medical, educational, industrial, and social work sectors is essential for success.

In conclusion, we feel that a quotation from the presentation made by Dr. Raymond A. Vonderlehr, Chief of the VD Division of the USPHS, during a critically important period of progress is highly relevant with respect to AIDS, just as it was with respect to syphilis. At the World Forum of Syphilis and Other Treponamatisos in 1962 he made the following statement:

And, finally, as a senior citizen and one who has spent the great majority of his professional career in this struggle against syphilis, I feel it appropriate that I sound a word of warning. It is a well understood precept in a free society that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance. And, if we in our time are to free this nation of syphilis infection, we must remain ever steadfast in our will and determination to see this current struggle through to a successful conclusion. If we have learned anything from the past, it is the fact that syphilis will not just go away because we would wish it so. We should now be aware and ever remain aware that this highly contagious disease will require our eternal vigilance and vigorous effort when the trend line of syphilis incidence inevitably approaches the end point of eradication. For it will be in this critical period that pressures will develop from many quarters to cease and desist the great impetus that is now being built up. Unless there is raw courage, rare determination, and a united will, the forces of reaction and complacency will gain the upper hand and history will again be repeated. This must not happen in a civilized society. I am firmly convinced that you assembled here, your associates at home and the people everywhere will stand up and be counted to the very end—no matter what the cost nor how great the effort must be—so that this generation can say with justifiable pride, “Syphilis we have no more. . . .

The philosophy expressed by Dr. Vonderlehr is one which can serve as a guide to the public health professions as they move forward to deal with AIDS as well as with the many other sexually transmitted diseases.

REFERENCES

1. Brandt AM: No Magic Bullet: A Social History of VD in the us since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

2. Vonderlehr RA, Heller JR Jr: The Control of Venereal Disease. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946; 5–8.

3. Williams RC: The United States Public Health Services 1798–1950: Commissioned Officers Association of the USPHS. Bethesda, MD USPHS, 1951; 154–156.

4. Mahoney JF, Arnold RC, Harris A: Penicillin treatment of early syphilis: A preliminary report. Vener Dis Inform 1943; 24:355–357.

5. US Army Medical Dept: Preventive Medicine in World War II, Communicable Diseases. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, Dept of the Army, 1960; 158.

6. Anderson OW: Syphilis and Society—Problems of Control in the United States 1912–1964. Chicago, IL: Center for Health Administration Studies, Health Information Foundation, Research Series 22, 1965.