Four

THE LAST OF THE 11TH

AND THE END OF AN ERA

In 1940, two new camps were constructed in San Diego and Imperial Counties—Camp Seeley, near El Centro, and Camp Morena, near Campo. Camp Seeley was used for desert training, and Camp Morena was used for mountain and cold weather training.

By 1941, the two camps were combined into a larger single camp named Camp Lockett. Camp Lockett was named for James Lockett, who was awarded two Silver Stars for “gallantry in action against insurgent forces” in the Philippines and had been stationed there with the 11th Cavalry in 1918. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the 11th Cavalry and later the 10th Cavalry were stationed on the site. There was widespread fear that Japan would cross the Mexican border into California. The 11th Cavalry was led by Lt. Col. Frederick Herr.

San Diego was designated as a strategic location due to its location on the Pacific coast and the Mexican border. The decision to send horse-mounted cavalry instead of tanks was due to the rugged and mountainous terrain. Many of the hills, gorges, and valleys would have been too difficult for mechanized equipment to maneuver.

The 10th and 24th Cavalry Regiments were the last horse cavalries to be posted at Camp Lockett. San Diego’s Camp Lockett was the last designated mounted cavalry camp constructed and the last active horse cavalry. The entire camp was closed on April 30, 1946, and later was used as a veterans’ convalescent hospital and an Italian prisoner of war camp for over 300 people.

The shift in warfare operations from the horse to the tank was finalized by the end of World War II.

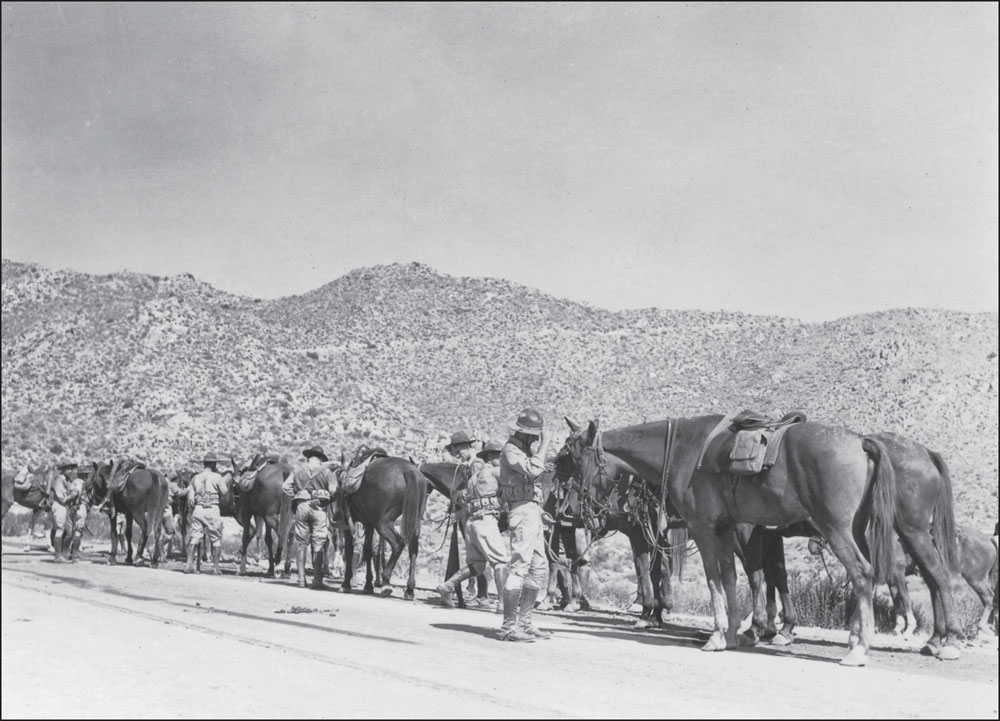

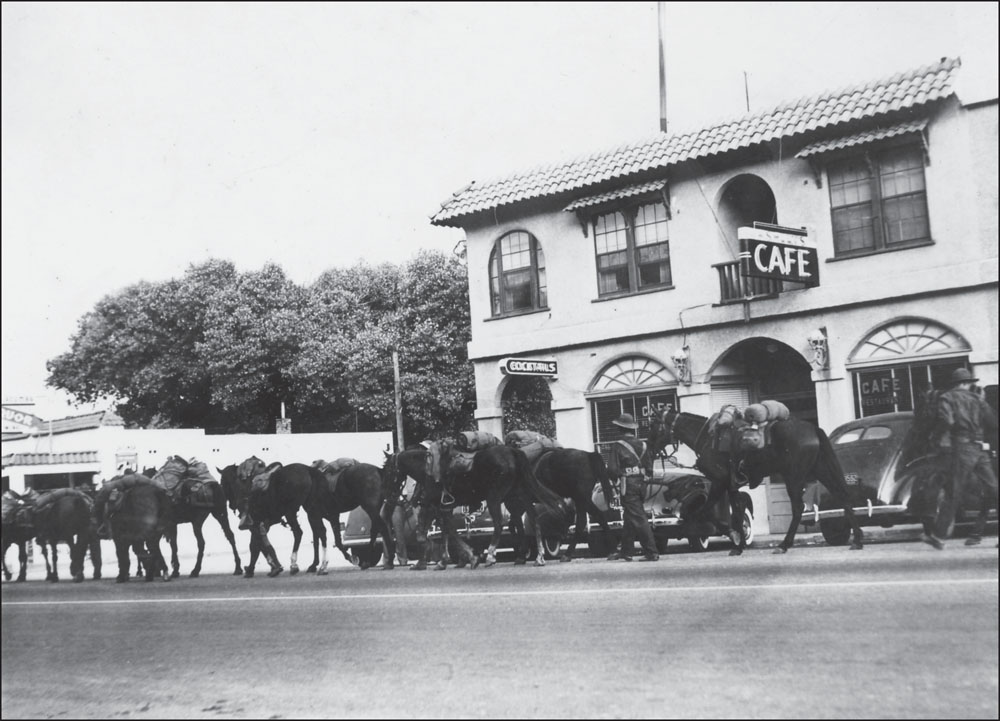

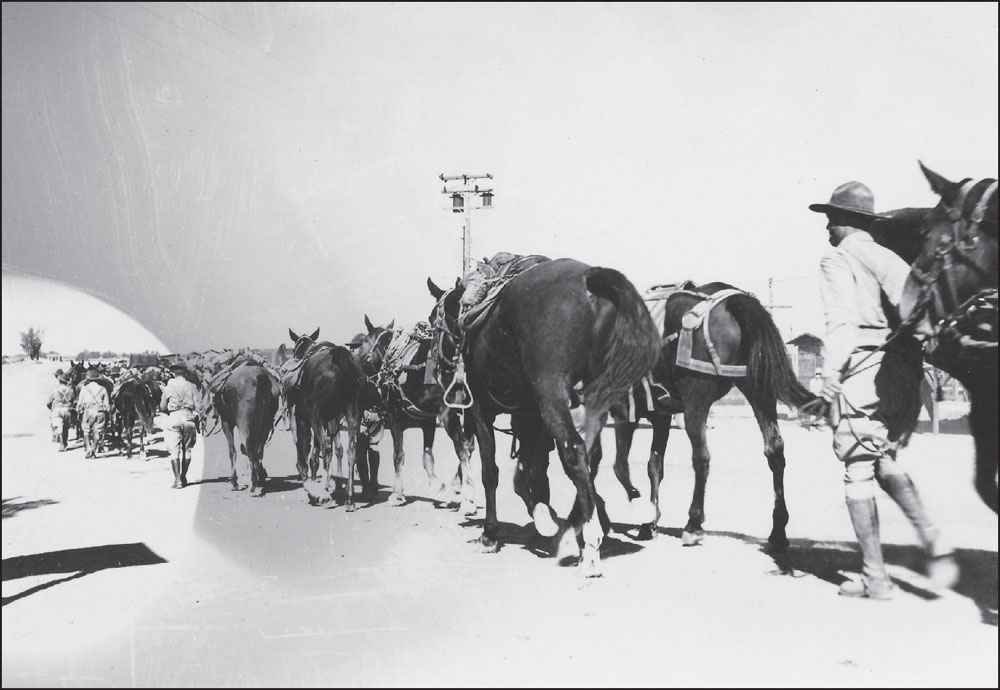

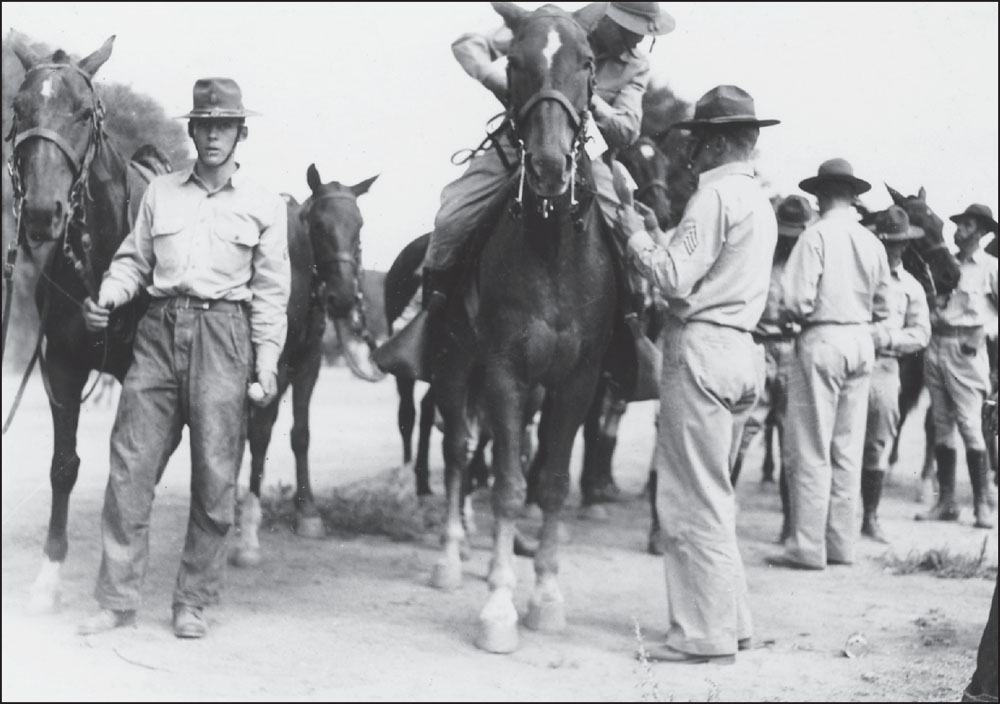

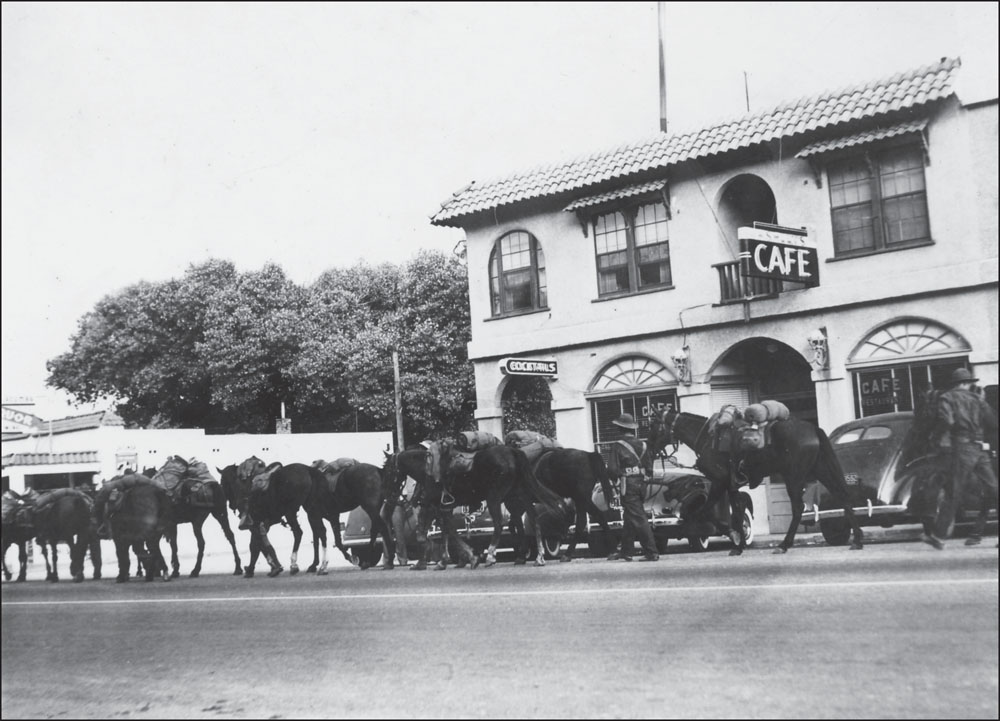

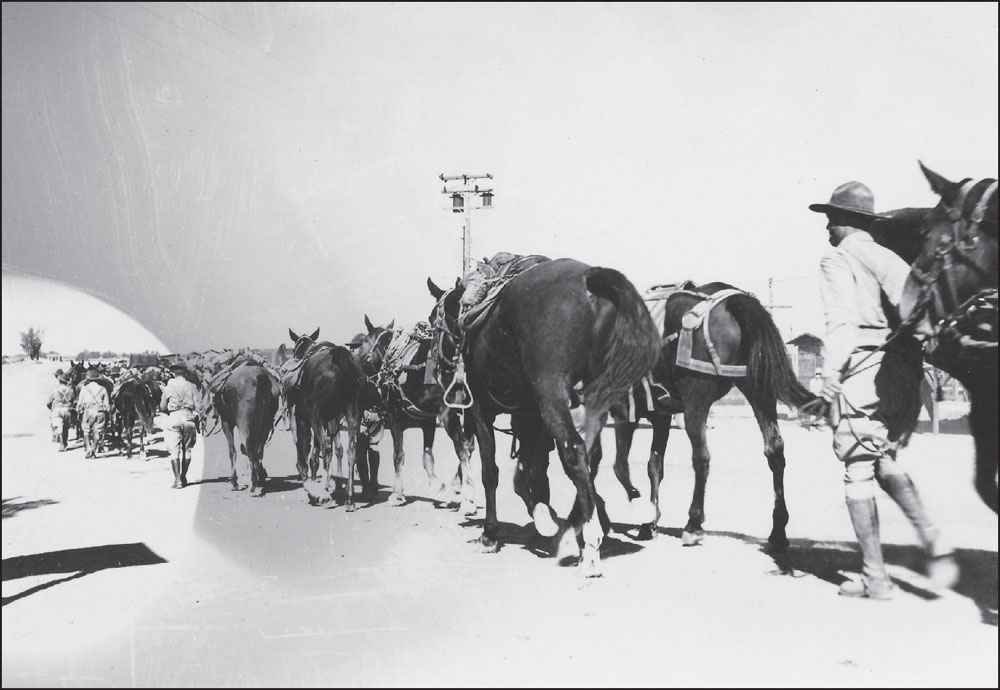

In this picture, horses and cars are used simultaneously; this was the last time horses would have such a significant role. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the 11th Cavalry Regiment moved quickly to Camp Lockett, arriving only two days later.

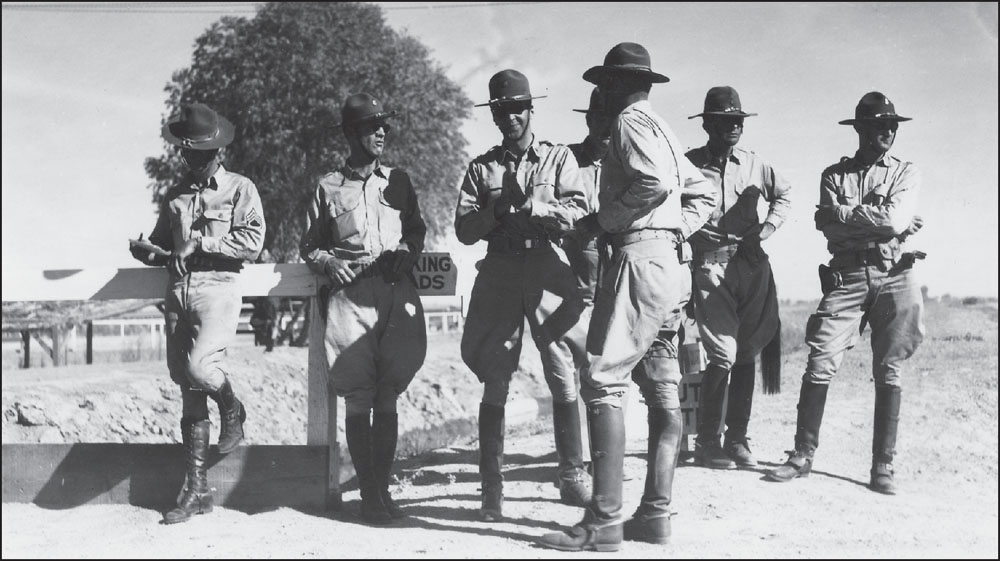

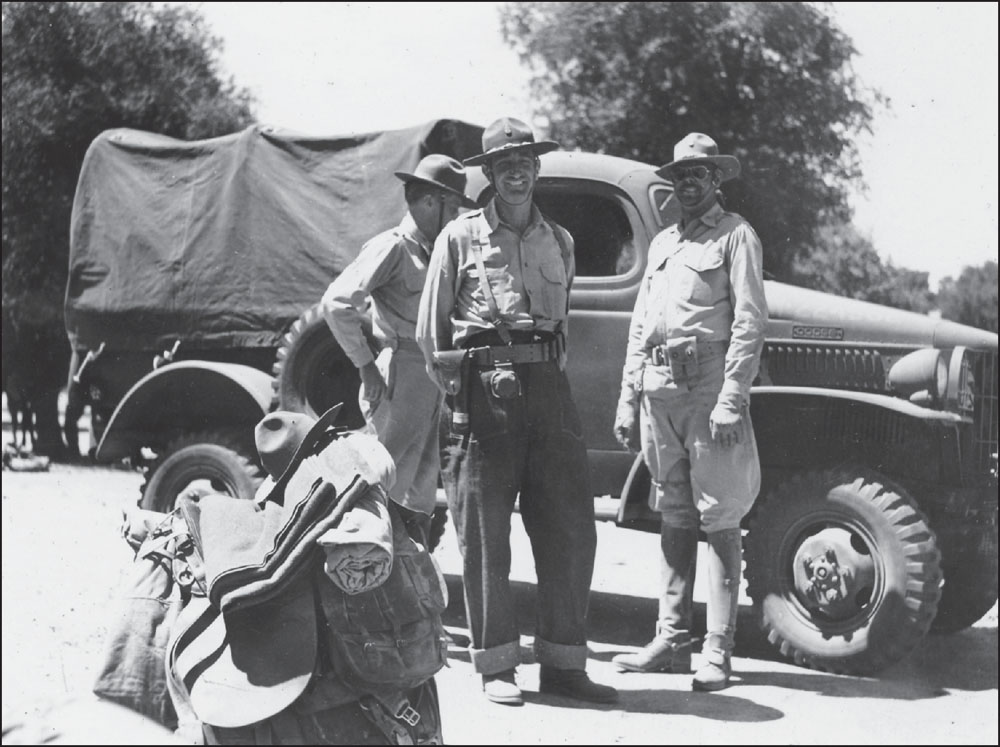

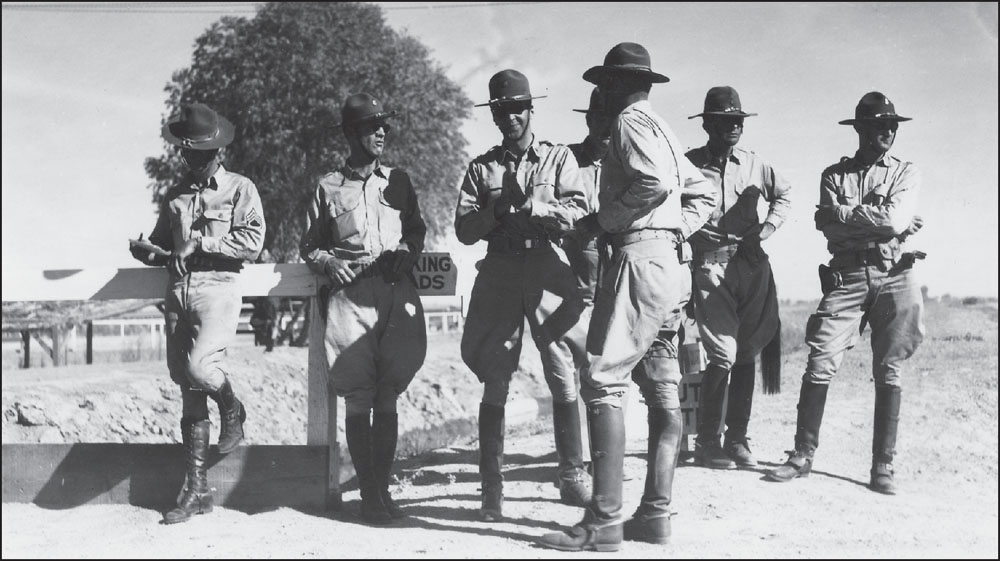

Camp Lockett, established in June 1941, was new for these officers of the 11th Cavalry, who arrived two day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

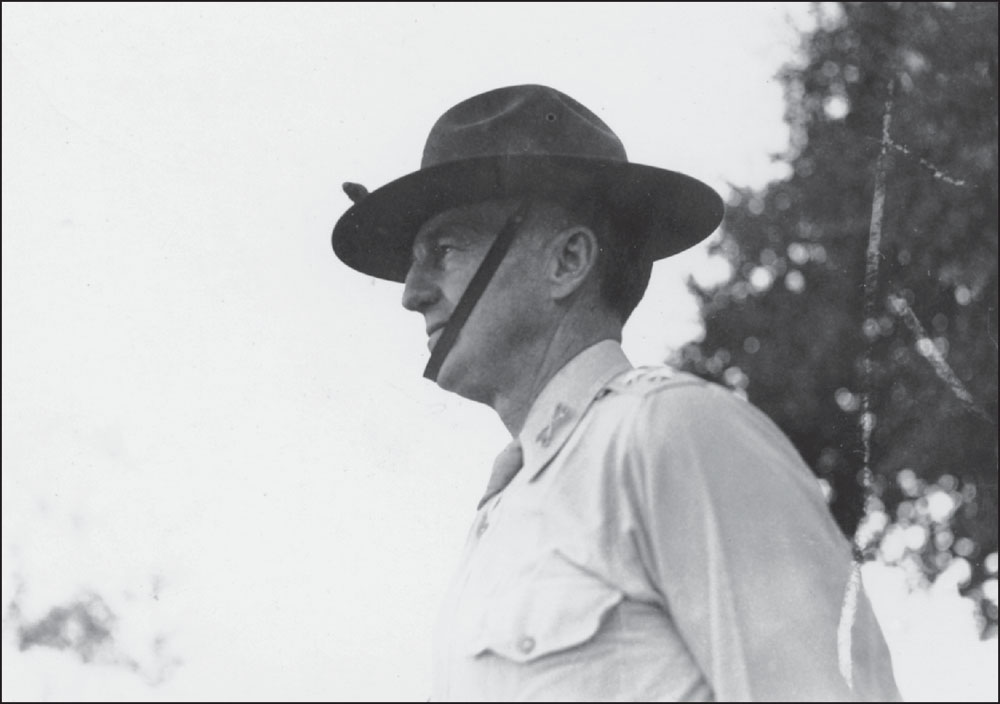

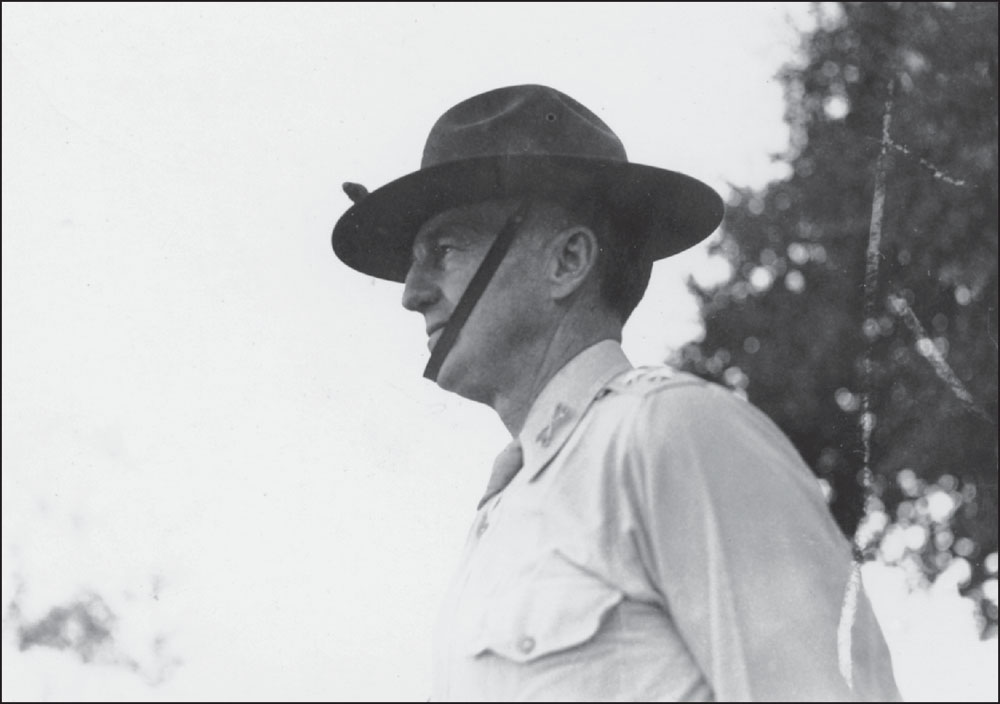

Lt. Col. Frederick Herr replaced Colonel Rayner as commander. Lucian K. Truscott Jr. in The Twilight of the US Cavalry, describes Herr as “tall, lean and rugged ... the picture of a Cavalryman. Active and energetic, he was a fine horseman and one of the Army’s best polo players. A magnetic and pleasing personality, he was greatly admired and respected on all sides.”

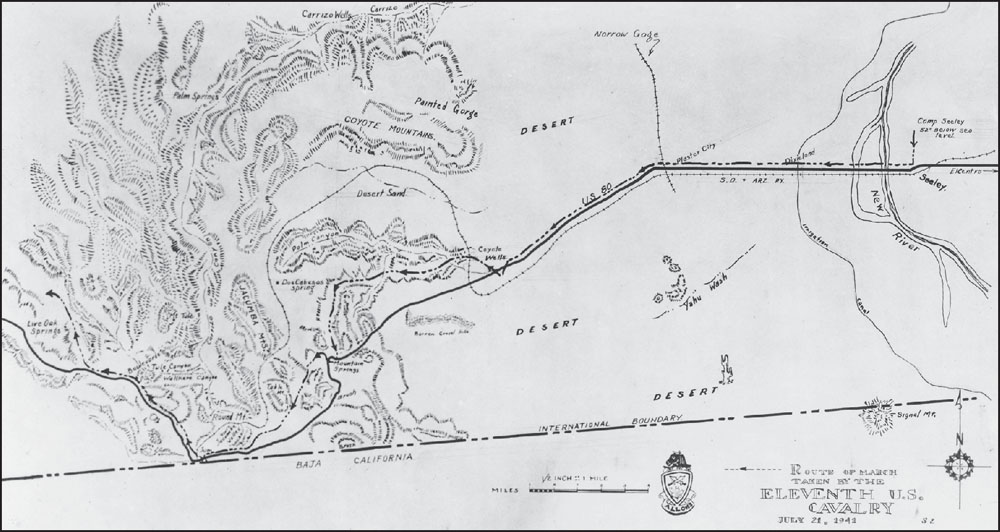

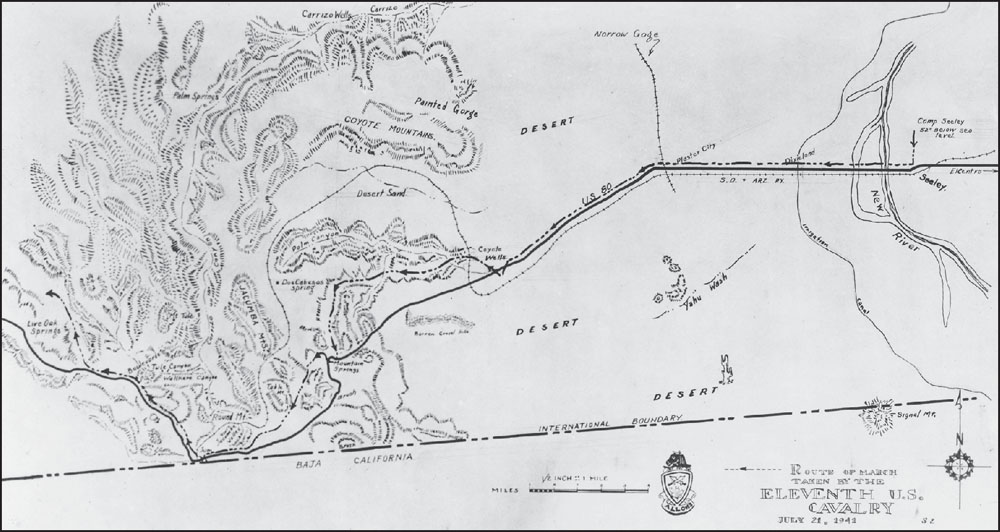

This map shows the route of the 11th Cavalry in a training operation, which became known as the Live Oak Springs Maneuver. On a hot July evening, the 11th Cavalry set out on a march from Seeley to Live Oak Springs. This area was and is the present-day home of the Campo Kumeyaay Nation.

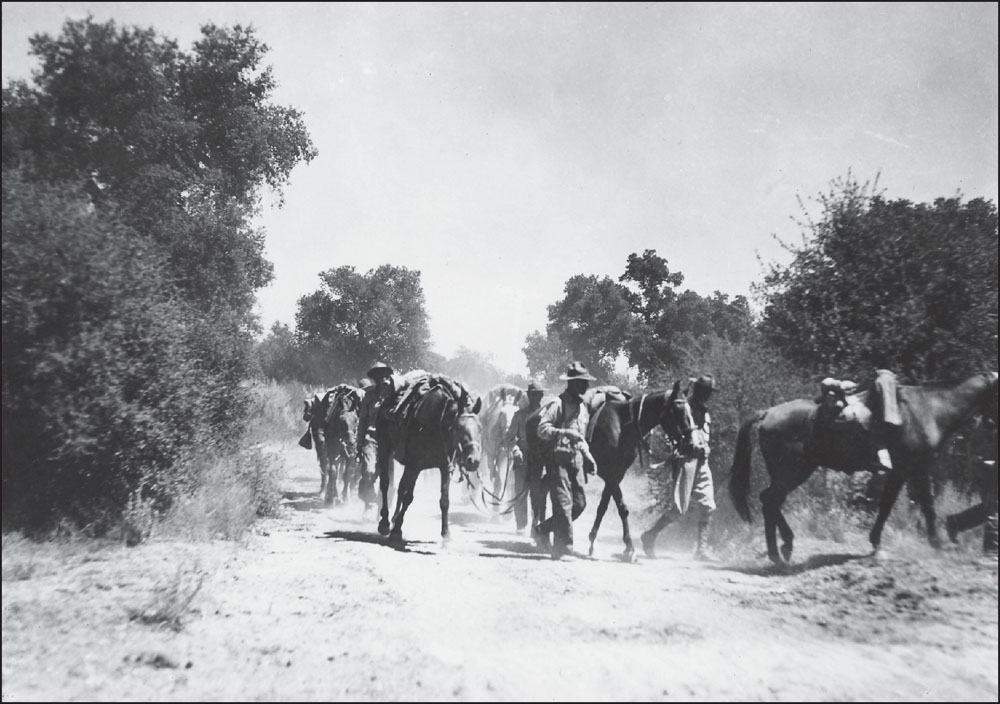

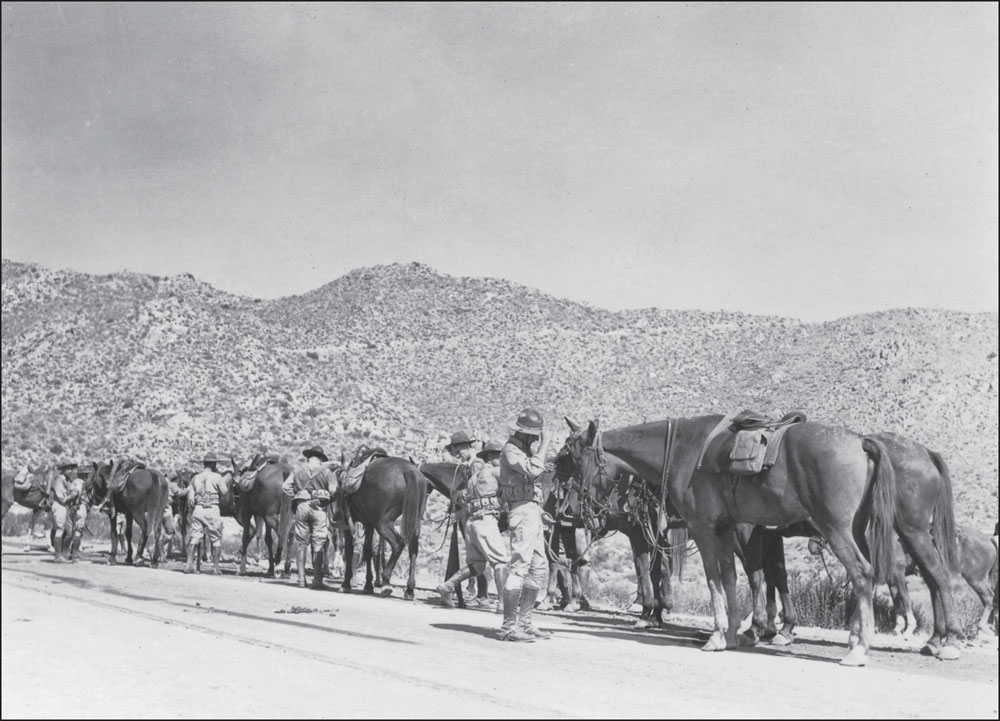

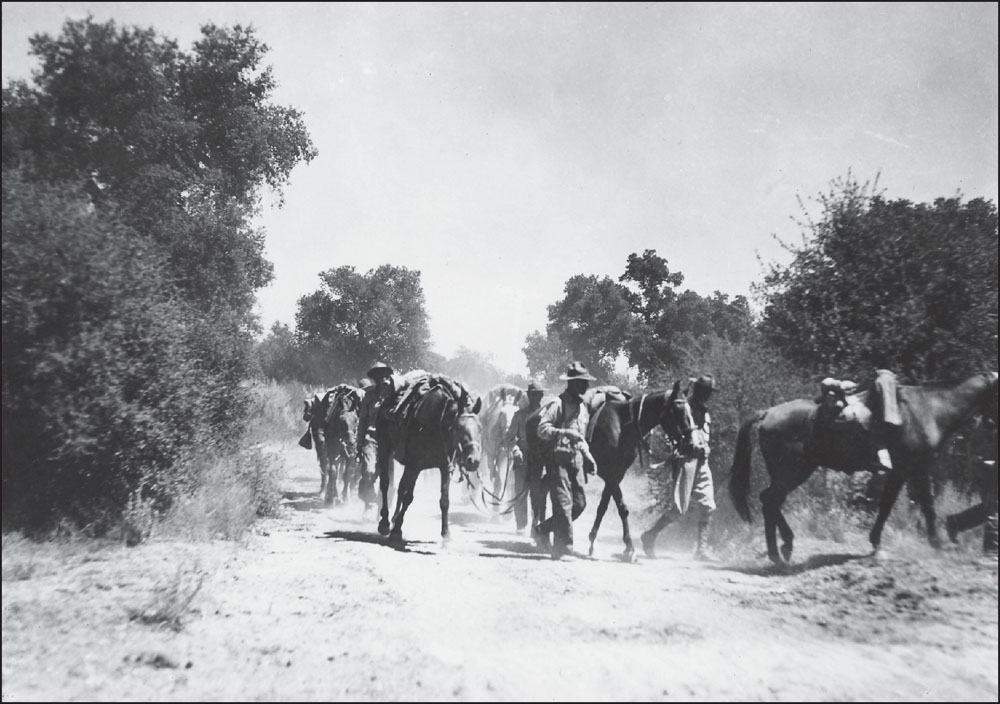

Capt. H.J. Rosenberg recounts one particular hazardous crossing through the mountains on the way to Live Oak Springs where “the men leading pack horses with short halter shanks had to lean backwards in their saddles.”

Colonel Rayner led the Live Oak Springs Maneuver, a desert march through the mountains of thick chaparral. Many of the cavalry recall the hazardous and challenging conditions of the march before reaching Jacumba, where they were able to rest before their final practice assault on Live Oak Springs.

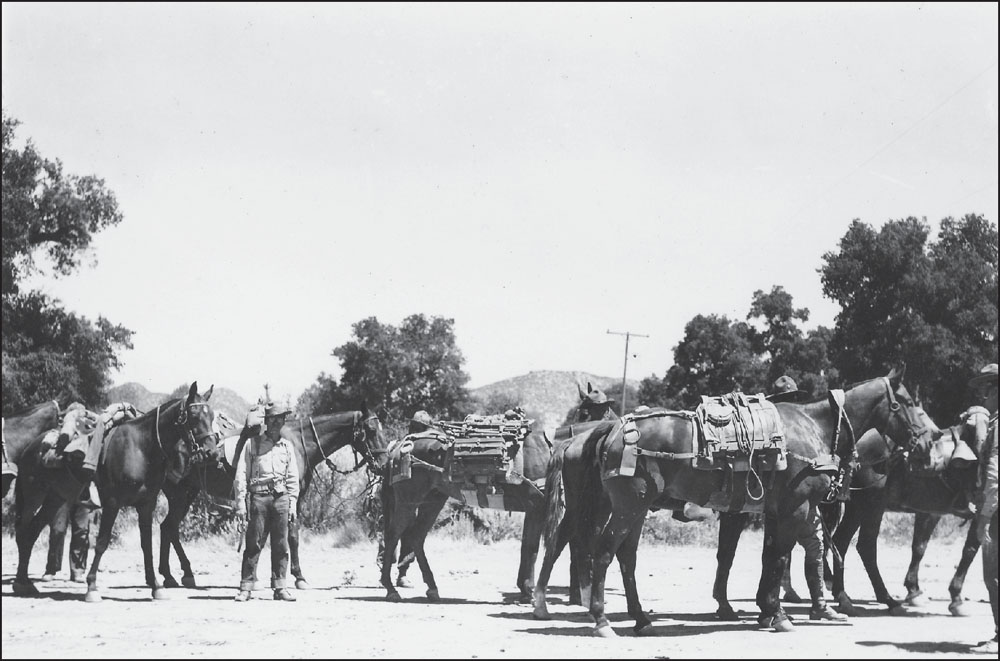

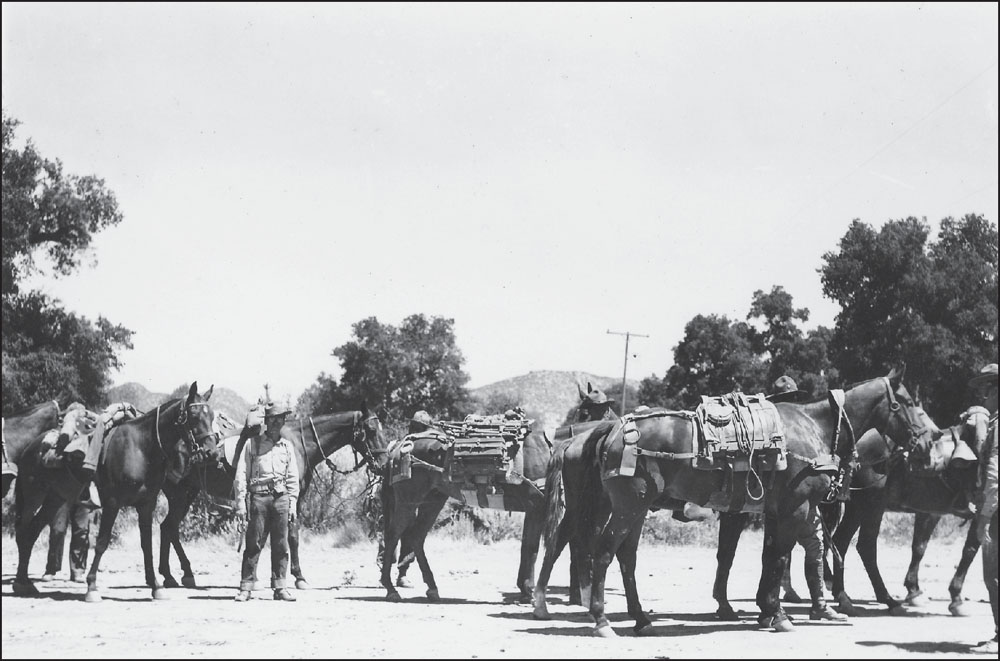

The personnel and items on the march to Live Oak Springs, according to Capt. H.J, Rosenberg, included “Six scout cars bristling with machine guns, 684 mounted men armed with pistols and rifles, thirty officers, three cyclists armed with submachine guns, pack horses bearing machine guns, mortars and special weapons, seventeen trucks, a semitrailer truck, a sedan, a pickup, two sidecars, and two reconnaissance cars.”

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, San Diego was seen as a vulnerable location. Ports and borders were reinforced and guarded. The US Cavalry in California was sent to protect the Mexican border. The cavalry was different from past cavalries in that there were equal parts machines and horses.

An important job was keeping the horses fed and watered. An enormous amount of grain and hay was needed to feed the horses and mules daily. At times, the amount could easily be 800,000 pounds a day, roughly 400 wagonloads. If needed, pasturage was used as a supplement for short periods.

These troops are making a few sandwiches. Making numerous sandwiches at a time was not an easy task.

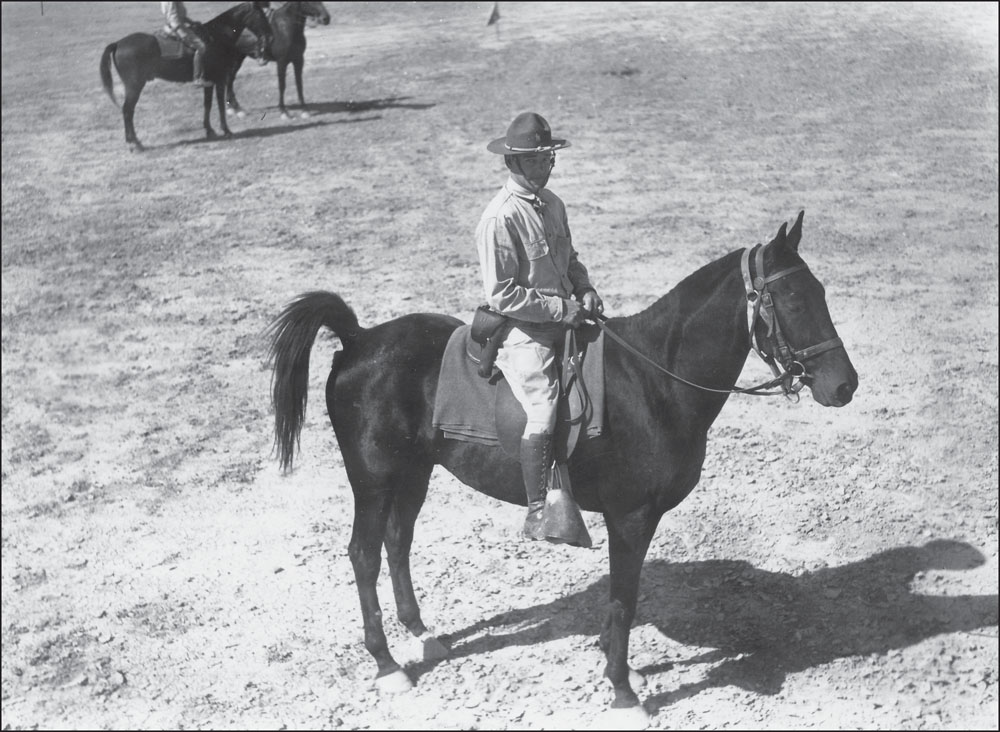

Valerie Read, daughter of Myron A. Thom, recalls that Lt. Col. Frederick Herr was easy to spot, with his erect posture and his beautiful black horse.

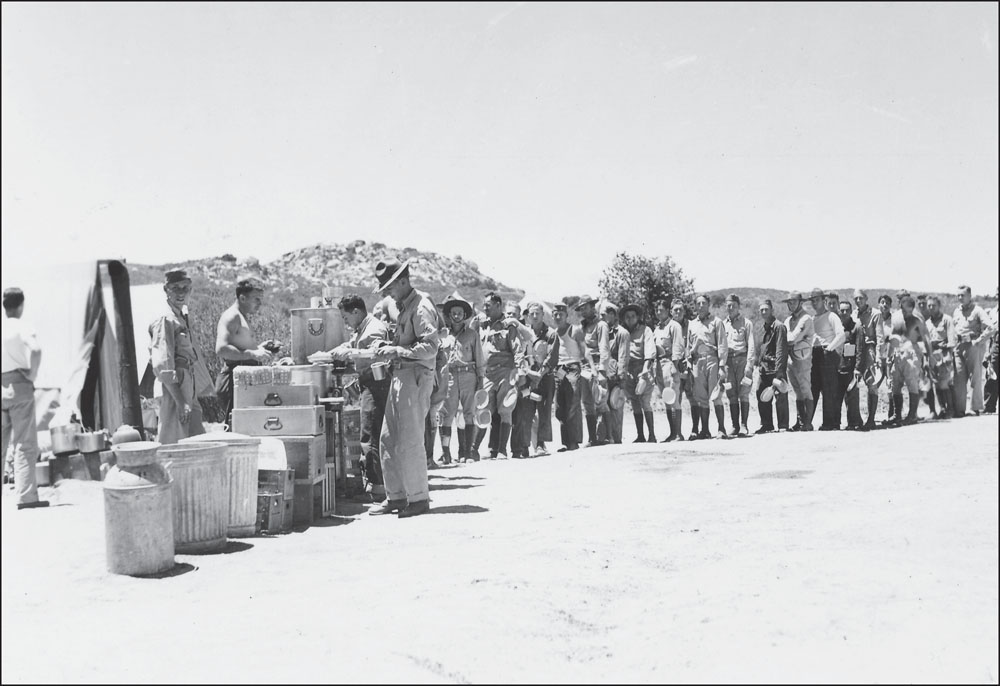

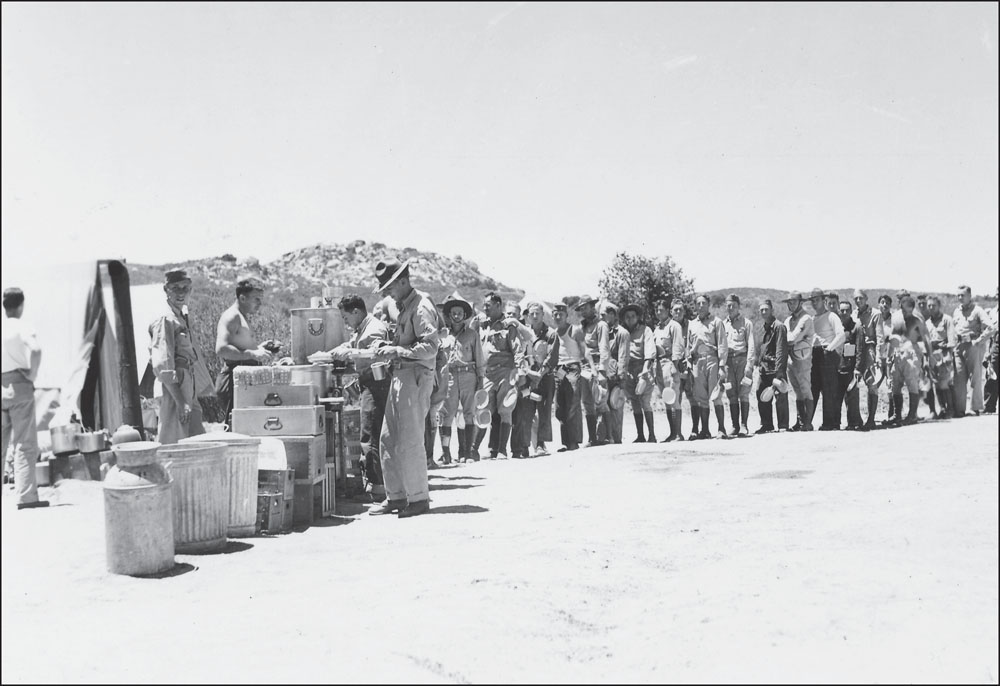

Food lines were almost as long as payday lines. A cavalry custom for many years was waiting in line for chow. Some recall that the food was not necessarily very good, but it was always very welcomed.

Soldiers were trained to lay flat on the ground when firing; this allowed for visibility of targets while not being a target oneself. Horses were also trained to lay down.

Lines were long for dinner, and every member of the regiment was happy when he finally arrived at the pot.

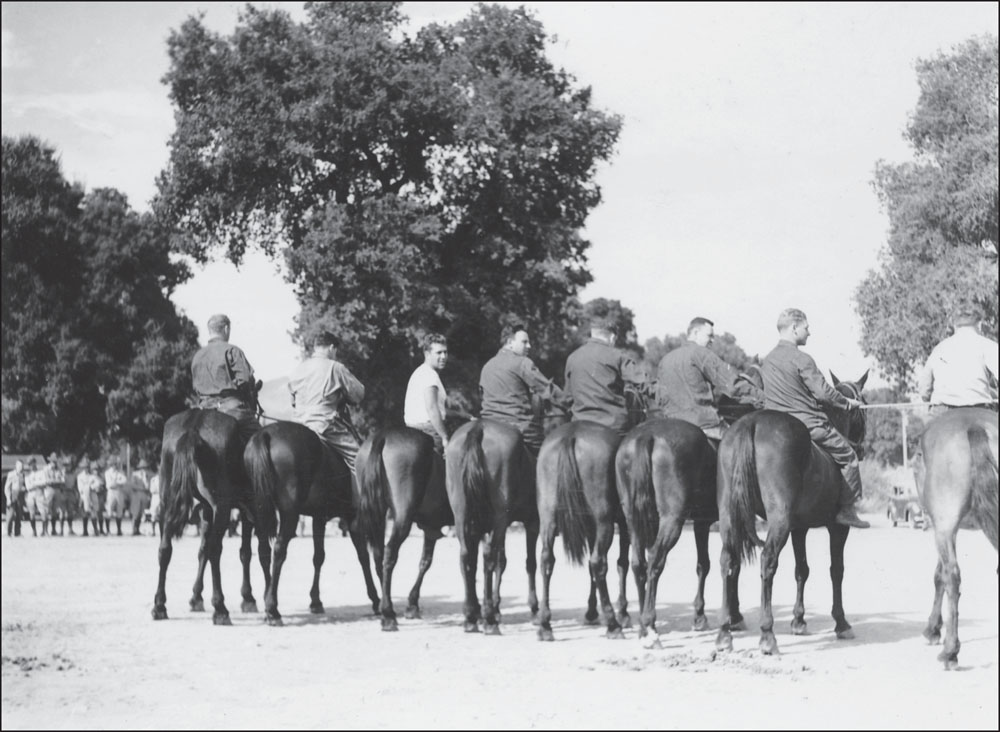

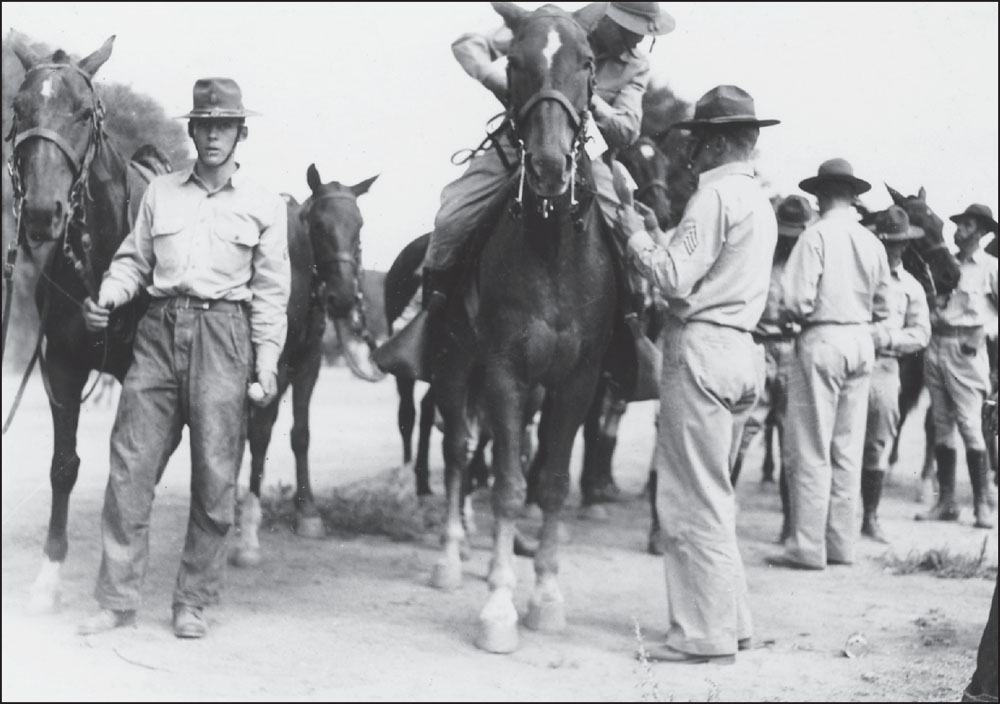

Here, soldiers pose with their horses in the area that was originally home to the Kumeyaay Nation. The Kumeyaay Nation owned the coastal area south of the San Luis Rey River to Punta Santo Thomas and east from the Salton Sea into Ensenada.

With the completion of the newly built Camp Lockett and the immediate influx of cavalry personnel after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the once-quiet border town became a busy and active military post.

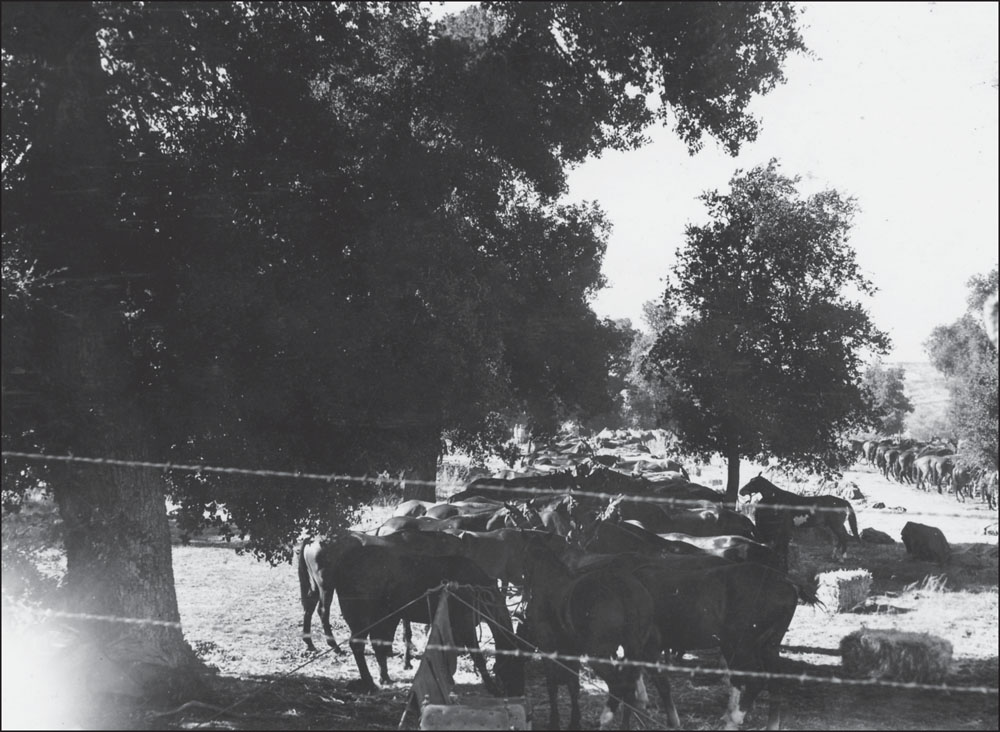

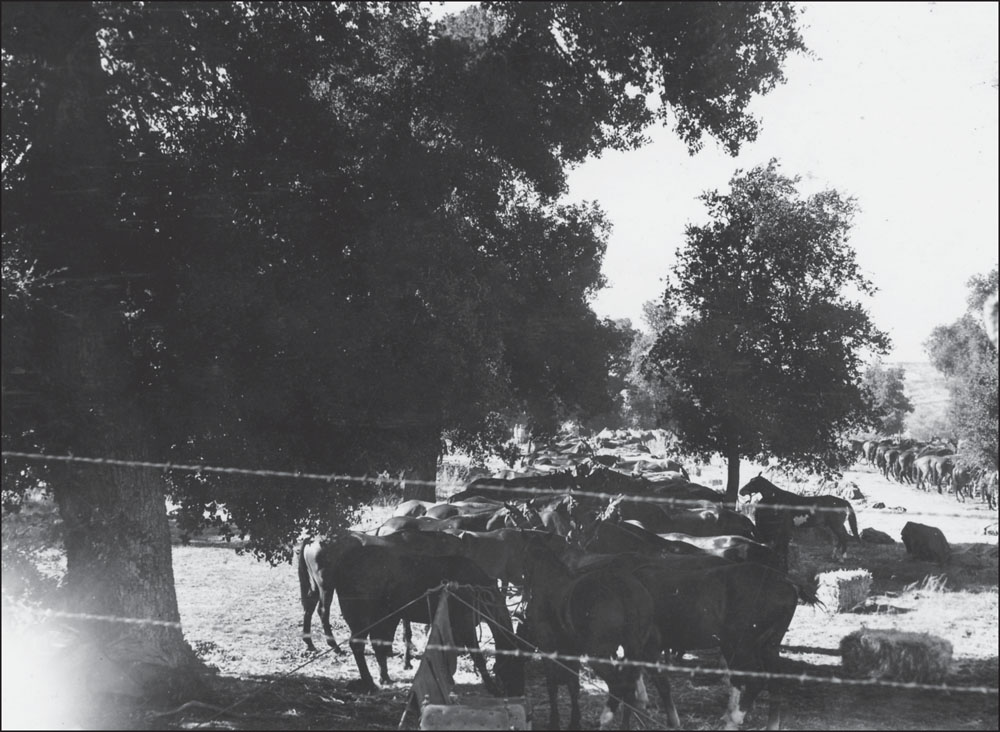

A corral has been quickly made with the help of barbed wire. The invention of barbed wire in the late 1880s changed land, grazing, and usage rights almost overnight. Many Native nations were restricted from normal land use by barbed wire. The mounted cavalry used it as a fast, cheap way to control people and horses.

Camp Lockett was built as a horse cavalry camp. The hills, valleys, and desert chaparral provided the perfect environment to practice drill for the horses, the soldiers, and the new mechanical cars and weaponry.

Here, packhorses carry artillery and supplies. Horses were soldiers too, and their riders knew it was important to work together. Often, horses could sense the enemy before their riders did.

A saddled horse and a packhorse walk side by side. The cavalry first occupied this site in 1878 when 16 troopers camped for several months. Then, in 1918, Troop E of the 11th Cavalry was stationed while en route from San Diego to Yuma.

On field maneuvers, the woody underbrush, rocky outcroppings, and many small streams were excellent conditions for troopers to practice battle strategies, horse and military tactics, and basic instruction.

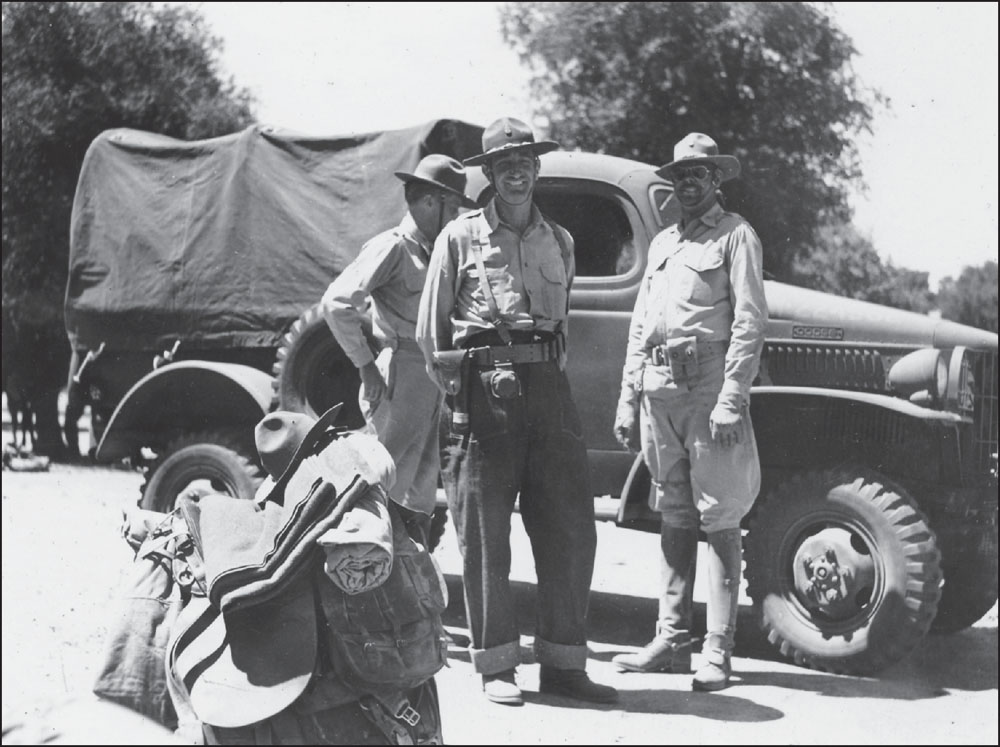

In a prophetic image, three cavalrymen pose with a saddle pack in front of them and a covered truck behind them; it is a scene of things to come.

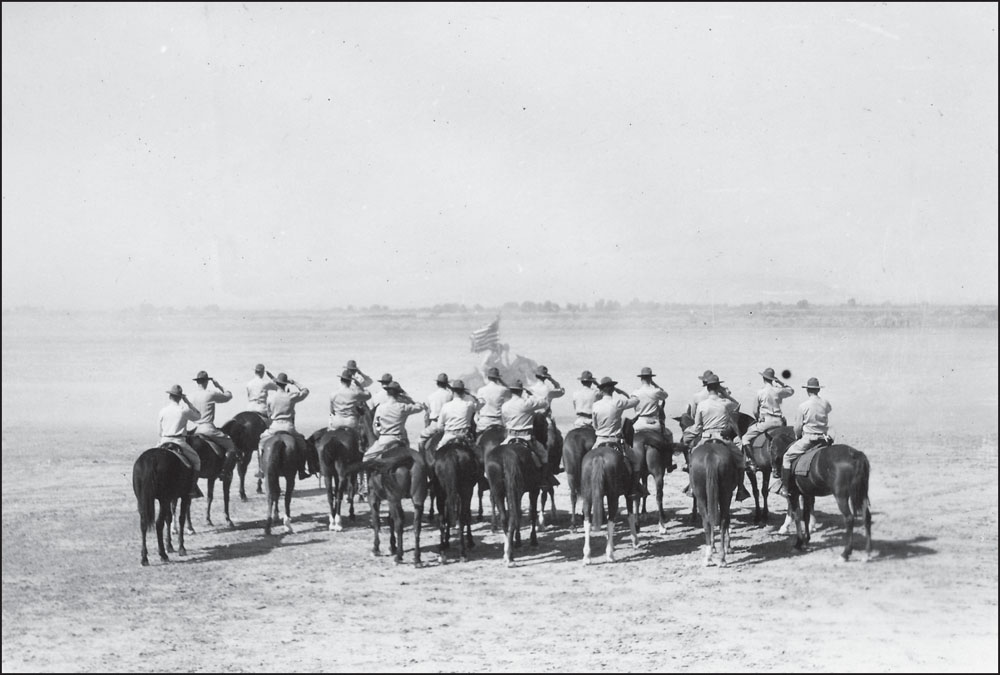

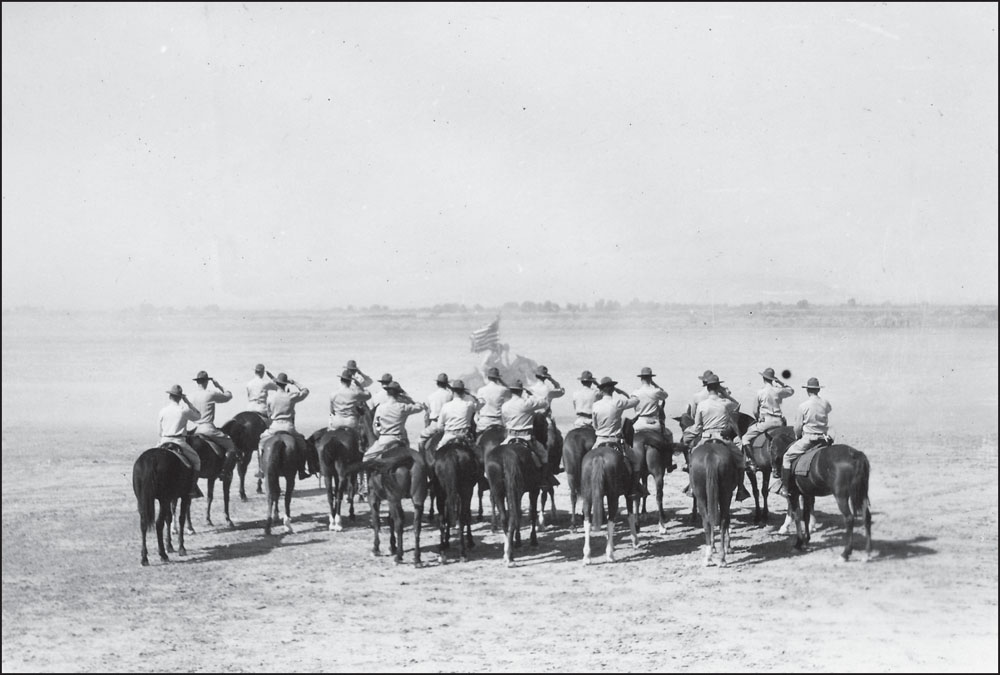

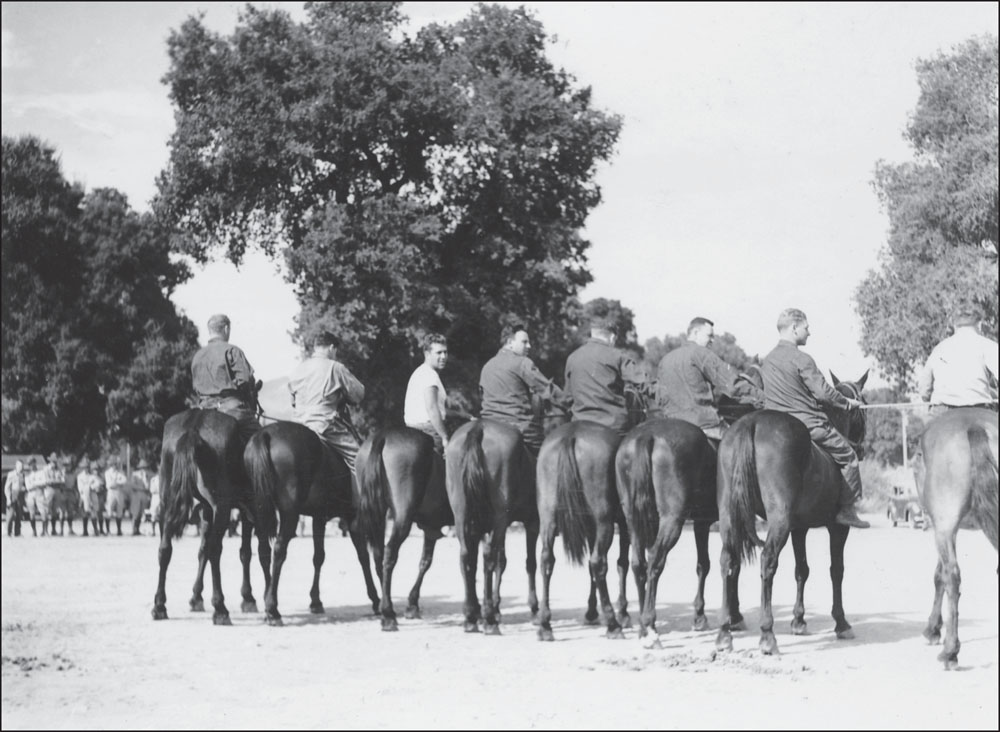

Saluting the colors, these men are either getting ready for review or for the field day events. The color guard presents the colors before important formal events.

Pictured are horses being tethered together. Troopers and horses had to contend with extreme climate changes. Often, the days could heat up to 110 degrees, while the night temperatures could drop drastically to 50 degrees.

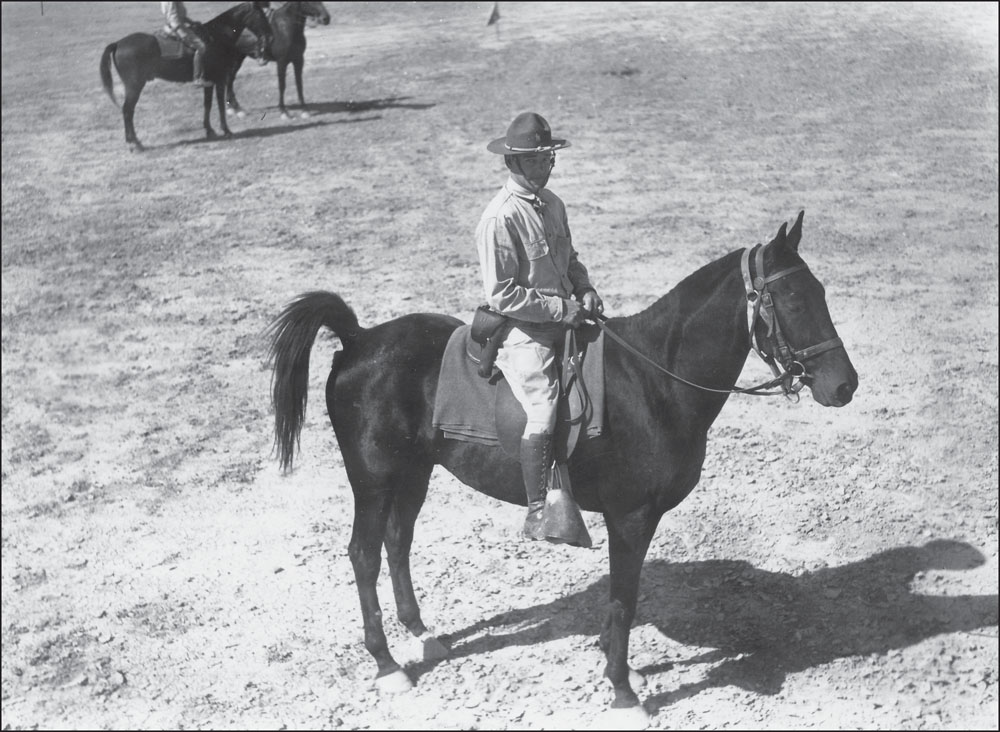

Lt. Col. Frederick Herr is seen here on his horse. Herr was the “last chief of the cavalry,” according to Lucian K. Truscott Jr. in The Twilight of the US Cavalry. Herr fought to reinstate the branch in large numbers and fought so strongly for reinstatement that he was in constant conflict with the war department.

When the 11th Cavalry arrived, members were greeted with new permanent barracks, a commissary, post office, horse stables, a hospital and veterinary building, officers’ quarters, mess hall, blacksmith shops, hay sheds, recreation buildings, and a chapel.

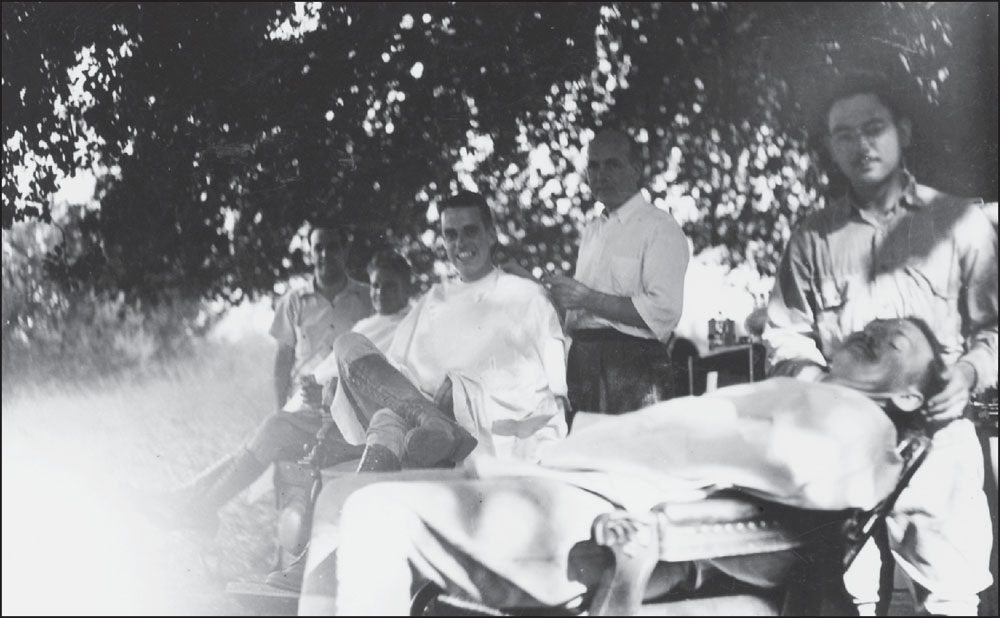

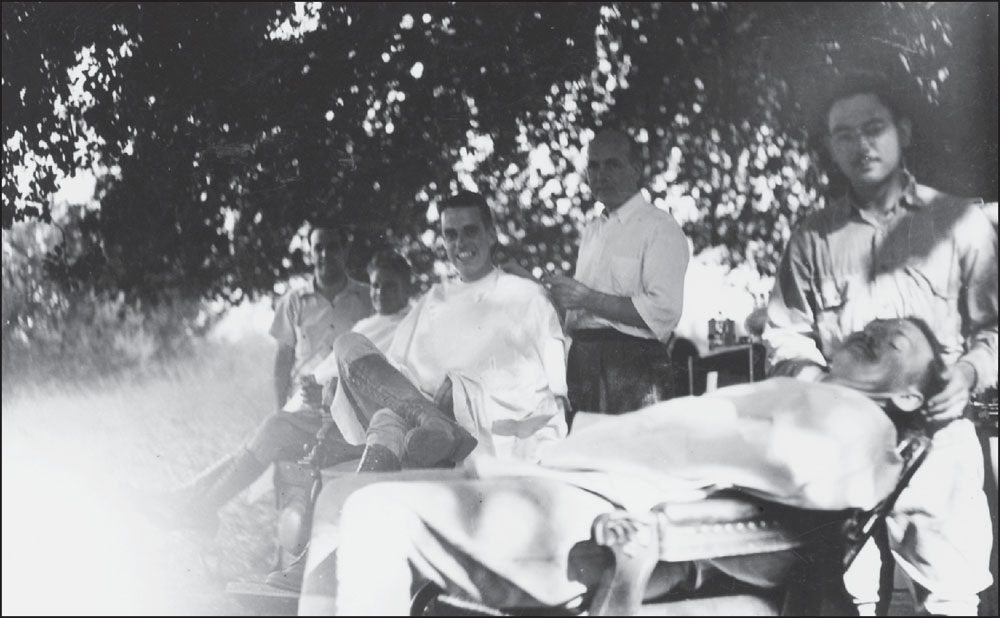

These soldiers are getting shaved in the shade. When on field maneuvers or on marches, temporary housing, kitchens, mess halls, and even barbershops had to be set up.

The mounted cavalry has a long history of camp dogs. Some pets were acquired on the way and were taken care of by one solider or often the entire troop. Dogs had been used in the military for centuries, and in World War II, they were trained to find trip wires, mines, and traps. Dogs also served as sentries.

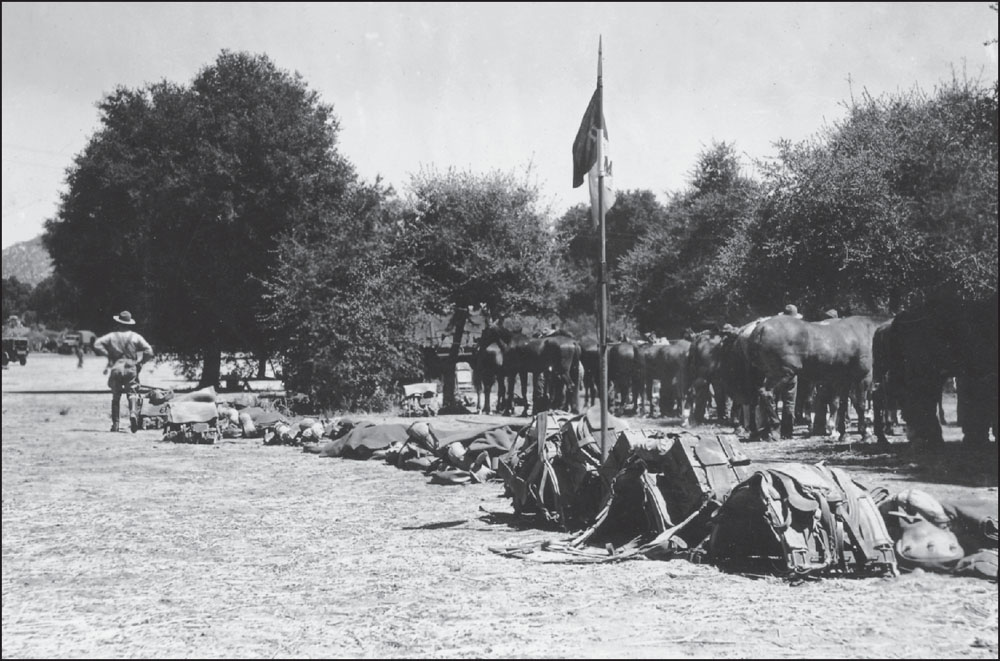

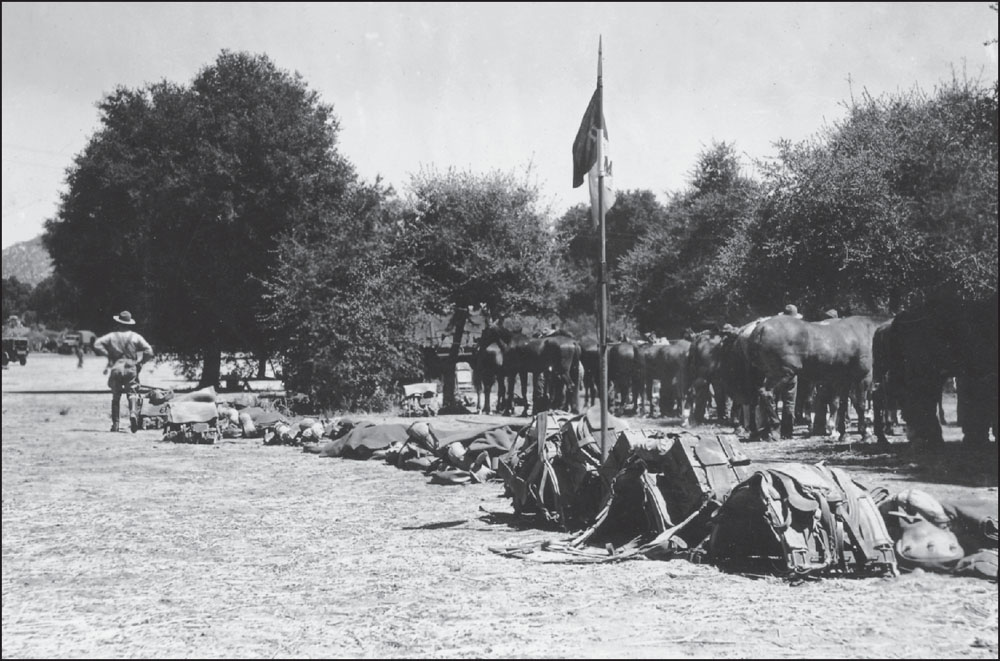

These horses are taking a break; their saddles are in a row behind them. The saddles and packsaddles could be quite heavy. Maneuvers often meant trotting and galloping with rider and supplies.

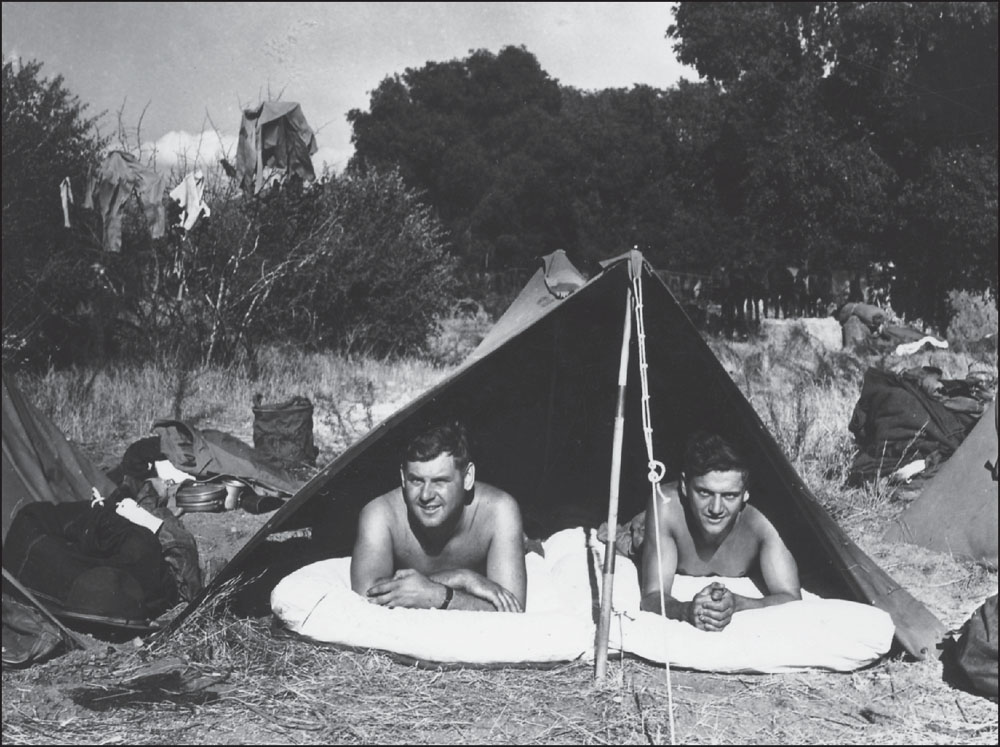

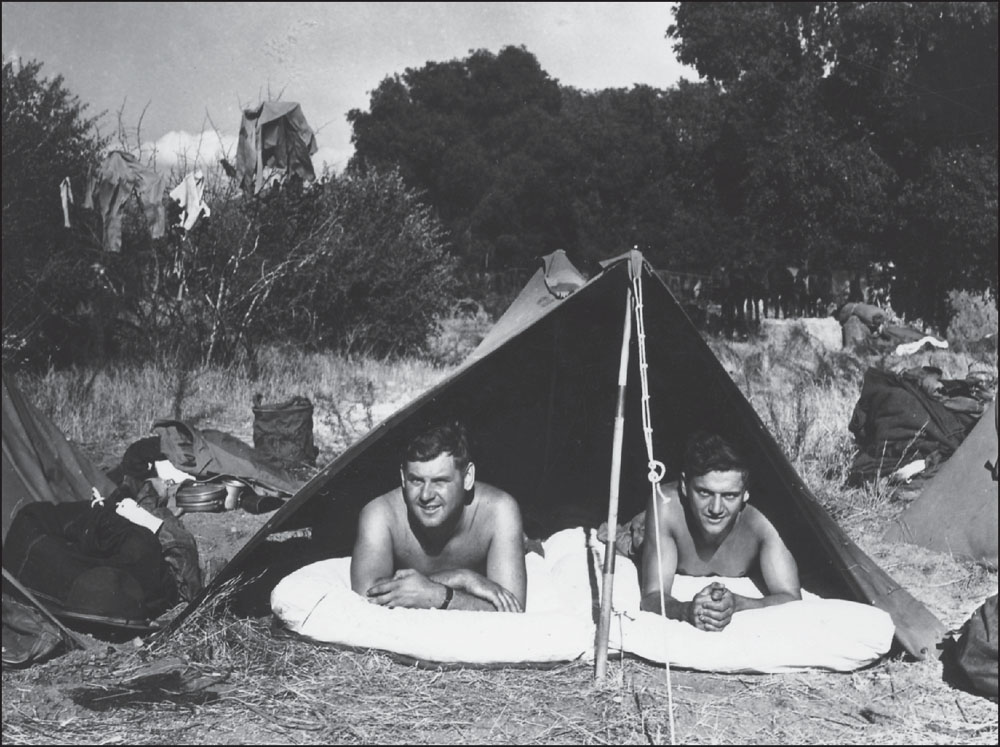

These two soldiers are trying out the tent while on drill training.

Horses were required to respond to various commands and cues. The horses were also trained not to respond to loud noises such as gunfire.

Water for the horses was required every day when on the march, and a group was sent ahead to locate some. If the water was far from camp, the horses were sent to water in groups, which could put the regiment at a strategic disadvantage.

Practice reconnaissance missions were performed with various scenarios.

Here, men appear to be conferring and checking their maps. Sometimes going off the road required another look at the map.

Resting the horses was important too.

By 1942, the 10th Cavalry replaced the 11th Cavalry, and a year later, the 28th joined the 10th and formed the 4th Cavalry Brigade of the 2nd Cavalry Division.

Training exercises and special events became more common as the threat of imminent danger from Japan subsided. Here, the colors are presented before a review of a riding and shooting competition between troops.

During the Civil War, the cavalry horses were carefully bred Morgans and Thoroughbreds. After the westward expansion, the horses were bought from local dealers. The cavalry of the westward expansion had to find horses that could compete with the Mustang of the plains.

Water was scarce in this area, and so as part of the planning phase, the Army petitioned the San Diego City Council for permission to use water from the Morena Reservoir six miles northwest of Campo. The request was approved, and as part of the contract, the “expense of installing and operating the necessary pipeline, meter, pumps, and treatment facilities shall be borne by the government.”

The man on the left is checking the time. Camps, even temporary ones, were run on precision timing. Meals, drills, and feeding and watering horses were all scheduled for thousands of men.

Mealtime means finally sitting down to eat. Meals generally included bread and various types of beans, along with bacon, beef, hardtack, eggs, and sugar.

The horse would carry the trooper’s spare clothing, toiletries, rations, mess gear, horse grooming equipment, ammunition, and personal items in the saddlebags; added to that is the rolled feed bag attached to the pommel with a grain bag enclosed within.

This trooper is practicing with a machine gun on a tripod. The trooper wore the .45-caliber pistol, gas mask, and basic ammunition load; the M1 rifle was carried on the horse.

The 11th Cavalry horses are pictured around 1942 beginning their march through Campo. The town, which was close to the border, had a customs house and immigration office along with a general store, hotel, and cafe.

Myron A. Thom, in the center, holds a found cat. Myron Thom was the veterinarian of the camp, and although most of his patients were equine, a few others slipped into his office.

In The 1862 US Cavalry Tactics, Philip St. George Cooke emphasizes the importance of choosing a temporary campsite with the horses in mind, stating that “it is sometimes necessary to encamp without water, chiefly with view to grass.”

Myron A. Thom is seen jumping his horse. Thom was the veterinarian for the 11th Cavalry. He received his doctorate of veterinary medicine from Washington State University and was deployed, along with the rest of the 11th, two days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Here, Lt. Col. Frederick Herr jumps his horse. Herr was the last chief of the cavalry; he fought hard to keep the full mounted cavalry as a branch of the Army, but mechanization proved to be the downfall of the horse and the mounted cavalryman.

This was the end of an era. The last of the mounted US Cavalry served in World War II, both in America and abroad, but not in the same numbers as it had in the past. With postwar development of mechanical weapons, the US Army eliminated horses entirely from service. The last surviving tactical cavalry horse, Chief, remained on government rolls until 1968.