THEIR PRESENCE CHANGED THE WORLD

• • • • • • •

Global communications, global travel, global impact. The twentieth century was a time of great change, with no innovations more representative of the period than these three. As they did for commerce and politics, they affected the inner lives of people in unforeseen and profound ways that have yet to be fully understood.

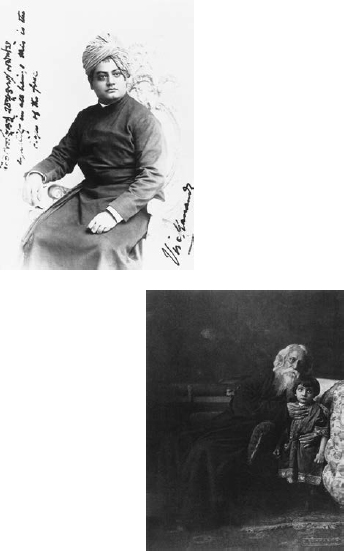

The advances began slowly—at least that is how it appears in hindsight, given the dizzying pace of change that marked the century’s waning decades. Swami Vivekananda, for example, died soon after the century began, and the extent of his impact seems, at first glance, limited. In fact, the appearance of this exponent of Hinduism’s Vedantic path at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1893 set the stage for the West’s broad acceptance of Eastern spirituality, which followed decades later.

Vivekananda’s work, it can be argued, also opened the way for the critical and popular acceptance afforded Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. Through Tagore the core values of Indian culture—peace, tolerance, unity, and divine love reflected in human love—gained appreciation in the West and were incorporated into the century’s utopian vision of a global village steadily progressing toward an idealized human society, which, it was assumed, would follow.

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s long-lasting impact was of another sort. As a theologian, teacher, and social activist, he helped restore a lost mysticism to mainstream American Judaism while leading his community into the modern era of interfaith dialogue and interracial social action.

In five short years Pope John XXIII set in motion changes within the Roman Catholic world that transformed the church beyond anything it has experienced in modern history. There has been no turning back from the Second Vatican Council convened by John, whose papacy was among the shortest of the twentieth century. Reform became the watchword, and the changes he initiated continue to convulse the Catholic world as it seeks to balance modernity and tradition.

John, then, was an unlikely spiritual revolutionary. The same might be said for Ram Dass, the middle-class son of acculturated American Judaism who was once a tenured professor at Harvard University named Richard Alpert. But just about all that John and Ram Dass have in common is the willingness to follow the spirit of experimentation, wherever it might lead, that so characterized the 1960s. For Ram Dass that spirit led to psychedelic drugs—and then to the path blazed by Vivekananda and Tagore, Eastern mysticism. And as John became an icon to a generation of liberal Catholics, Ram Dass became an icon to a generation turned on by recovery of a spirit it found lacking in contemporary Western society.

But when it comes to impact, none in the century approach Billy Graham, Tenzin Gyatso, better known as the fourteenth Dalai Lama, and Pope John Paul II. Each in his own way is an example of that unique late twentieth century’s creation: the spiritual leader as pop celebrity and commodity. Not since the rise of Islam, the newest of the world’s great religions, has a spiritual leader affected the global stage to such a degree.

Graham, confidant of presidents and kings, transformed the Protestant tent revival into a worldwide multimedia stadium extravaganza. The Dalai Lama employed a lighthearted touch to make Buddhism, the ornate Tibetan branch in particular, fashionable to non-Buddhists everywhere, including Hollywood celebrities. John Paul turned the papal Mass into the religious equivalent of a traveling rock tour, and the Vatican into a political powerhouse on issues of morality.

Of the three, the Dalai Lama is the youngest. But even he is no youngster. When these three pass from the scene, their legacies will endure for decades, if not longer. Take nothing away from their forceful personalities and indomitable spiritual strengths. But give a fair share of the credit for their international impact to the ease with which global communications and travel were made possible at the close of the twentieth century.

(1935–)

• • • • • • •

For the past half century, since he was forced to flee his Tibetan homeland, Tenzin Gyatso, better known as H. H. (His Holiness) the Dalai Lama, has inspired the world with his wisdom, compassion, and courage.

He was born to a peasant family, but when he was two, Buddhist lamas from Tibet’s capital city, Lhasa, were led to his remote house by special indicators, including images in their dreams. There they tested whether he could identify certain significant items left behind by the thirteenth Dalai Lama (literally, “Ocean [or Great] Teacher”), the spiritual leader of Tibet who had recently died. The infant Gyatso passed the tests and was declared the fourteenth Dalai Lama, a reincarnation of his predecessor. Three years later he was enthroned in his palace in Lhasa. His new role also made him de facto political head of the country.

In 1951 Communist troops from China invaded Tibet and reclaimed it as a Chinese territory for the first time in centuries. As part of subsequent truce negotiations, the Dalai Lama was formally made the head of the now regional Tibetan government. In 1959, after years of small, sporadic rebellions by native Tibetans, the Chinese launched a massive repression. Thousands of Tibetans were killed, hundreds of Buddhist temples and monasteries were destroyed, and the Dalai Lama felt compelled to go into exile. He settled just beyond Tibet’s southern, Himalayan border in the Indian city of Dharamsala, where he gradually attracted a community of displaced Tibetans and disciples that currently numbers more than one hundred thousand.

Forced into exile by the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the Dalai Lama has traveled extensively, acting as an advocate for conflict resolution by peaceful means.

During his years of exile, the Dalai Lama has traveled extensively, keeping the Tibetan cause alive on the international stage while spreading the Buddhist dharma (teachings) and acting as an advocate for conflict resolution by peaceful means. His engaging personality shines through in his books, several of which have been New York Times bestsellers. In 1989 he received the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts.

HIS WORDS

The more altruism we develop in a day, the more peaceful we find ourselves. Similarly, the more self-centered we remain, the more frustrations and trouble we encounter. All these reflections lead us to conclude that a good heart and an altruistic motivation are indeed true sources of happiness and are therefore genuine wish-granting jewels. —Path to Bliss, p. 18

A sad human being cannot influence reality. If you are sad or depressed, you cannot influence reality. When you face a so-called enemy, that enemy only exists on a relative level. Then, if you harbor hatred or ill feelings toward that person, the feeling itself does not hurt the enemy. It only harms your own peace of mind and eventually your own health.

—The Buddha Nature, p. 78

Books by the Dalai Lama

The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living. New York: Riverhead, 1998.

The Buddha Nature. Woodside, Calif.: Bluestone Communications, 1996.

The Buddhism of Tibet. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 1975.

Ethics for a New Millennium. New York: Penguin Putnam, 1999.

The Good Heart. Somerville, Mass.: Wisdom Publications, 1996.

Kindness, Clarity, and Insight. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 1984.

My Land and My People. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

An Open Heart: Practicing Compassion in Everyday Life. Edited by Nicholas Vreeland. Boston: Little, Brown, 2001.

Path to Bliss. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 1991.

A Policy of Kindness. Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications, 1990.

Books about the Dalai Lama

Avedon, John F. In Exile from the Land of Snows. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

Farrar-Halls, Gill. The World of the Dalai Lama: An Inside Look at His Life, His People, and His Vision. Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing, 1998.

Morgan, Tom, ed. A Simple Monk: Writings on His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Introduction by Robert Thurman. Photographs by Alison Wright. Novatoa, Calif.: New World Library, 2001.

Organization

Tibet Center, 359 Broadway, New York, NY 10013; phone and fax: 212-966-8504.

Other Resources

Web sites: www.tibet.com. Web site of the Government of Tibet in Exile.

www.savetibet.org. Web site of the International Campaign for Tibet.

Videotape: Compassion in Exile, documentary, Lemle Pictures, 1992; available from Direct Cinema Limited, P.O. Box 10003, Santa Monica, CA 90410; phone 310-396-4774.

Film/Videotape/DVD: Kundun, dramatization, Touchstone Pictures, directed by Martin Scorsese, 1997.

“The more altruism we develop in a day, the more peaceful we find ourselves.”

(1918–)

• • • • • • •

The foremost Protestant evangelist of the twentieth century, the Reverend Billy Graham has employed the latest in technology and marketing techniques to modernize the format and style of traditional revival meetings, attracting large audiences worldwide. Many of his contemporaries became associated solely with political conservatives, but Graham befriended and advised U.S. presidents of both major parties, while consistently preaching the need to make a personal decision to live for Jesus Christ. And at a time when many prominent religious figures were tainted by sexual or financial misdeeds, he remained free from scandal.

Born near Charlotte, North Carolina, Graham committed his life to Christ at a revival in 1934. He was ordained five years later by a Southern Baptist church, studied at the Florida Bible Institute (now Trinity College), and graduated from Wheaton College in Illinois in 1943. He joined Youth for Christ, which spread the Gospel to servicemen, and became a rising star in the world of evangelism. In 1949 his stardom was sealed by a Los Angeles crusade that extended more than five weeks past its original three-week target. Around the same time the media mogul William Randolph Hearst boosted Graham’s career by ordering that positive stories be written in his newspapers about the evangelist.

Graham’s first overseas crusade was held in 1954 in London. Three years later more than two million people attended a sixteen-week crusade at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Graham established the Hour of Decision radio show in 1950 and staged his first televised crusade in 1957. He has written a newspaper column and penned eighteen books, and his ministerial organization has produced numerous evangelistic films. His message has been consistent and simple: Surrender to Jesus and you will be saved. He talks little of hell, social or political concerns, intellectualized theology, or denominational concerns.

In tent meetings and revivals for over fifty years, Graham’s message has been consistent and simple: Surrender to Jesus and you will be saved.

Throughout his career Graham has consulted with and advised U.S. presidents. Although Harry Truman dubbed him a counterfeit, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and Bill Clinton all met with him. He offered the prayer at Nixon’s 1968 inaugural and in 1991 appeared on television alongside President George H. W. Bush—who called him America’s pastor—at the start of the Persian Gulf War.

In his mid-eighties, Graham, slowed by age and illness, turned much of his ministry over to his son Franklin while still preaching. Franklin Graham continues the family tradition of advising American presidents; he is a confidant of President George W. Bush. Billy Graham has preached to more than 210 million people in over 185 countries and territories.

HIS WORDS

At the loneliest moments in your life you have looked at other men and women and wondered if they too were seeking—something they couldn’t describe but knew they wanted and needed. Some of them seemed to have found fulfillment in marriage and family living. Others went off to achieve fame and fortune in other parts of the world. Still others stayed at home and prospered, and looking at them you may have thought: “These people are not on the Great Quest. These people have found their way. They knew what they wanted and have been able to grasp it. It is only I who travel this path that leads to nowhere. It is only I who goes asking, seeking, stumbling along this dark and despairing road that has no guideposts.” But you are not alone. All mankind is traveling with you, for all mankind is on this same quest. All humanity is seeking the answer to the confusion, the moral sickness, the spiritual emptiness that oppresses the world. All mankind is crying out for guidance, for comfort, for peace.

—Peace with God, pp. 1–2

Billy Graham: The Inspirational Writings: Peace with God, The Secret of Happiness, Answers to Life’s Problems. n.p.: Budget Book Service, 2000.

How to Be Born Again. Dallas: Word Publishing, 1989.

Just as I Am: The Autobiography of Billy Graham. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1997.

For a more complete list of books by Billy Graham, see Just as I Am, pp. 741–742.

Books about Billy Graham

Drummond, Lewis, and John R. W. Stott. The Evangelist. Nashville: W Publishing, 2001.

McLoughlin, William G., Jr. Billy Graham: Revivalist in a Secular Age. New York: Ronald Press, 1960.

Paul, Ronald C. Billy Graham: Prophet of Hope. New York: Ballantine Books, 1978.

Walker, Jay. Billy Graham: A Life in Word and Deed. New York: Avon Books, 1998.

Wooten, Sara McIntosh. Billy Graham: World-Famous Evangelist (People to Know). Berkeley Heights, N.J.: Enslow Publishers, 2001.

Organization

Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, P.O. Box 779, Minneapolis, MN 55440; phone: 877-2GRAHAM. (In November 2001, Graham announced that the ministry’s headquarters would relocate to his native Charlotte, North Carolina, to a building on a street named for him.)

Other Resources

Web site: www.billygraham.org. Official web site of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Periodical: Decision, magazine founded in 1960, published by the BGEA, which features Graham’s messages.

“All humanity is seeking the answer to the confusion, the moral sickness, the spiritual emptiness that oppresses the world. All mankind is crying out for guidance, for comfort, for peace.”

(1907–1972)

• • • • • • •

Theologian, teacher, and social activist, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel profoundly influenced Jewish thinking in the late twentieth century. His writing expounded on Jewish mysticism and prophecy, and his fusion of Jewish scholarship with involvement in the civil rights movement made him a patron saint to legions of Jews who drew their spiritual inspiration from his example. He was also influential in improving Catholic-Jewish ties in the Vatican II era.

Born into a Hasidic dynasty in Warsaw, Poland, Heschel earned a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Berlin, an unusual foray into secular culture for someone with his background. He taught in Berlin and Frankfurt before leaving Nazi Germany for the United States, where in 1940 he joined the faculty of Hebrew Union College, a Reform Jewish seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio. But he never fit in religiously at the liberal school and five years later moved to the Jewish Theological Seminary, a Conservative Jewish school in New York, where he remained a professor of Jewish ethics and mysticism until his death.

Heschel’s belief that scholarship must be twinned with action led him to march with the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and photographs of the two walking arm in arm remain an indelible image from the era.

Heschel’s writings span an array of languages—German, Hebrew, Yiddish, and a lyrically beautiful English he acquired only late in life. In his books, both academic and spiritual, he formulated a philosophy of Judaism uniquely suited to his time while drawing on and encouraging the piety, spontaneity, and emotion of the Hasidism of his youth. He posited a God who yearns for human companionship as much as humans yearn for God, an “ineffable” divinity who suffers whenever his creations suffer and is deeply saddened when they sin. Heschel’s short work on the Jewish Sabbath, in which he called the seventh day a “palace in time,” remains a classic and much-read volume.

Heschel retained traditional Jewish observance throughout his life as he broke new ground in interfaith relations and social activism. A meeting with Pope Paul VI helped pave the way for Vatican II’s positive statements on Jews and Judaism, and in 1965 Heschel became the first Jew appointed to the faculty of Union Theological Seminary, the liberal Protestant seminary in New York. His belief that scholarship must be twinned with action led him to march with the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and photographs of the two walking arm in arm remain an indelible image from the era. Of his participation in the civil rights movement, Heschel said, “When I march in Selma, my feet are praying.”

Since his death in 1972, Heschel has grown in popularity among Jews and others seeking greater connectedness between spirituality and social action.

HIS WORDS

Time is like a wasteland. It has grandeur but no beauty. Its strange, frightful power is always feared but rarely cheered. Then we arrive at the seventh day, and the Sabbath is endowed with a felicity which enraptures the soul, which glides into our thoughts with a healing sympathy. It is a day on which hours do not oust one another. It is a day that can soothe all sadness away.

—The Sabbath, p. 20

Resorting to the divine invested in us, we do not have to bewail the fact of His shore being so far away. In our sincere compliance with His commands, the distance disappears. It is not in our power to force the beyond to become here; but we can transport the here into the beyond.

—Man Is Not Alone, p. 131

Books by Abraham Joshua Heschel

Between God and Man: An Interpretation of Judaism. New York: Free Press, 1997.

The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in Eastern Europe. Woodstock, Vt.: Jewish Lights, 1995.

Israel: An Echo of Eternity. Woodstock, Vt.: Jewish Lights, 1995.

Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion. New York: Noonday Press, 1997.

A Passion for Truth. Woodstock, Vt.: Jewish Lights, 1995.

The Sabbath. New York: Noonday Press, 1996.

Books about Abraham Joshua Heschel

Kaplan, Edward K., and Samuel H. Dresner. Abraham Joshua Heschel: Prophetic Witness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Moore, Donald J. The Human and the Holy: The Spirituality of Abraham Joshua Heschel. New York: Fordham University Press, 1989.

For a more complete list of books by and about Abraham Heschel, see Between God and Man, pp. 275–298.

Organization

Shalom Center, 6711 Lincoln Dr., Philadelphia, PA 19119; phone: 215-844-8494. Founded by Rabbi Arthur Waskow, the center reflects Heschel’s values and propagates his message. Articles on its web site (www.shalomctr.org) reflect on his legacy, and the center has set up a council to commemorate the annual anniversary of his death.

“It is not in our power to force the beyond to become here; but we can transport the here into the beyond.”

(1881–1963)

• • • • • • •

Although his papacy was among the shortest of the twentieth century, the impact of Pope John XXIII is still felt throughout the Roman Catholic world and beyond. The first pope in centuries to admit that the church was in need of reform, he convened the Second Vatican Council, setting in motion and supporting a major overhaul of Catholic life and worship. Vatican II substituted the vernacular for Latin in the Catholic Mass, improved interfaith and ecumenical relations, and generally revolutionized the church.

Born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli on November 25, 1881, he grew up the son of sharecroppers in Sotto il Monte, Italy, and entered a seminary at twelve. After a hiatus to serve in the Italian army, he was ordained in 1904 and was appointed secretary to the bishop of Bergamo. Following service as a military chaplain in World War I, he was appointed spiritual director of the seminary he had attended and was called to the Vatican in 1921 to reorganize the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. He then served the Vatican in a variety of roles around Europe before being named cardinal-patriarch of Venice in 1953.

His 1958 election as pope was a surprise. He was a compromise choice, winning on the twelfth ballot, his age, seventy-six, having made him attractive as a transitional leader whose papacy would be relatively short. He was expected to be a caretaker who would continue the policies of the long-serving Pius XII, but such was not the case.

Three months into Pope John XXIII’s papacy, he called for an ecumenical council—the first in over a century—to meet in Rome in 1962 and “bring the church up to date.”

Although it lasted only five years, the papacy of John XXIII was a busy and monumental one. Three months into his papacy he called for an ecumenical council—the first in over a century—to meet in Rome in 1962 and “bring the church up to date.” Vatican II radically changed the face of the church, internally and externally, and John imagined it a “New Pentecost,” or outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

Pope John XXIII was a strong voice for world peace and ecumenical relations. His encyclical Pacem in terris, “Peace on Earth,” was addressed to all of humankind. It reflected the fears of living in the nuclear age and called human freedom the basis of world peace. He created the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity and appointed the Vatican’s first representative to the Assembly of the World Council of Churches held in New Delhi. He traveled more than his predecessors and worked to depoliticize—and demystify—the papacy. He removed from the liturgy words offensive to Jews and on at least one occasion greeted Jewish visitors with the biblical quote “I am Joseph, your brother.”

He died on June 3, 1963, and was remembered fondly in the world media for his jovial nature and rotund figure, as well as for his accomplishments, even though the work of Vatican II was far from completed. In September 2000, Pope John XXIII was beatified, the second of three steps toward being declared a saint in the Roman Catholic Church.

HIS WORDS

The Council now beginning rises in the Church like daybreak, a forerunner of most splendid light. It is now only dawn. And already at this first announcement of the rising day, how much sweetness fills our heart. Everything here breathes sanctity and arouses great joy. Let us contemplate the stars, which with their brightness augment the majesty of this temple.

—Opening speech to Vatican II, in Documents of Vatican II

All must realize that there is no hope of putting an end to the building up of armaments, nor of reducing the present stocks, nor, still less—and this is the main point—of abolishing them altogether, unless the process is complete and thorough and unless it proceeds from inner conviction.

—Pacem in terris

Encyclicals and Other Messages of John XXIII. Washington: TPS Press, 1964. Includes Pacem in terris and Mater et magistra, his two most influential encyclicals.

Journal of a Soul. 1980. Reprint, Garden City, N.Y.: Image Books, 1999.

Books about Pope John XXIII

Feldman, Christian. Pope John XXIII: A Spiritual Biography. New York: Crossroad, 2000.

Johnson, Paul. Pope John XXIII. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974.

O’Brien, David, and Thomas Shannon. Catholic Social Thought: The Documentary Heritage. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1998.

For a more complete list of books by and about John XXIII, see Johnson, Pope John XXIII, p. 245.

Other Resources

Web sites: www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_ council/index.htm. The Vatican web site’s section on Vatican II. www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_xxiii/index.htm. The Vatican web site’s section on Pope John XXIII.

Grave: Basilica of St. Peter, in the Vatican. Has become a major pilgrimage site.

“The Council now beginning rises in the Church like daybreak, a forerunner of most splendid light.”

(1920–)

• • • • • • •

The first non-Italian pontiff in 456 years, Pope John Paul II has built bridges between the Roman Catholic Church and other religions even as he has reinforced his church’s traditional positions on controversial sexuality and gender issues, and the authority of the papacy.

Born Karol Jóƶef Wojtyła in Wadowice, Poland, he was an actor before being ordained a priest in 1946. By the time he became archbishop of Kraków in 1963, he was widely known for speaking out against Poland’s Communist government. In 1978 he was elected pontiff after the death of Pope John Paul I. He is the most widely traveled pope in history, having made multiple visits to the Americas, Australia and the Pacific islands, Europe, Africa, and Asia. In March 2000 he made a historic trip to the Holy Land, visiting both Israelis and Palestinians within borders the two groups dispute.

More than any other pope, John Paul II has fostered dialogue with non-Christians, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and members of various tribal religions. In his first year as pope he visited Auschwitz, the notorious Nazi concentration camp in his native Poland, in a gesture of outreach to Jews. In 1986 he became the first pope to pray in a synagogue, during a meeting with Roman Jews, and he later issued a pastoral letter condemning anti-Semitism as a sin. He has also reached out to non-Catholic Christian groups, notably meeting with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, titular leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which split with the Roman Catholic Church in 1054. The most overtly political modern pope, John Paul II has met with over five hundred heads of state and frequently comments on international issues, always urging justice and reconciliation. His staunch anti-Communism is credited with aiding Lech Wałesa’s Solidarity movement in Poland and helping to cause the Soviet Union’s collapse.

More than any other pope, John Paul II fostered dialogue with non-Christians, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and members of various tribal religions.

Under his leadership the church has also staunchly opposed abortion, the ordination of women, sexual promiscuity, birth control, and divorce while insisting upon priestly celibacy and the primacy of Rome’s authority in acceptable Catholic teaching. Yet John Paul II has steadfastly spoken for the poor and oppressed, and against capital punishment, moral ambiguity, and the excesses of capitalism and consumerism. He survived an assassination attempt in 1981 and continues to travel, offering himself as a sort of chaplain to the world despite his age and steadily deteriorating health.

HIS WORDS

The first and fundamental structure for a “human ecology” is the family, founded on marriage, in which the mutual gift of self as husband and wife creates an environment in which children can be born and grow up. Too often life is considered to be a series of sensations rather than as something to be accomplished. The result is a lack of freedom to commit oneself to another person and bring children into this world. The family is sacred; it is the sanctuary of life. It is life’s heart and culture. It is the opposite of the culture of death, the destruction of life by abortion.

—Centesimus annus, in John Paul II: The Encyclicals in Everyday Language, p. 190

The Church of Christ discovers her “bond” with Judaism by “searching into her own mystery.” The Jewish religion is not “extrinsic” to us, but in a certain way is “intrinsic” to our own religion. With Judaism, therefore, we have a relationship which we do not have with any other religion. You are our dearly beloved brothers, and, in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.

—Speech to representatives of the Jewish community in Rome, April 13, 1986, in John Paul II and Interreligious Dialogue, p. 72

The religiosity of the Muslims deserves respect. It is impossible not to admire, for example, their fidelity to prayer. The image of believers in Allah who, without caring about time or place, fall to their knees and immerse themselves in prayer remains a model for all those who invoke the true God, in particular for those Christians who, having deserted their magnificent cathedrals, pray only a little or not at all.

—Crossing the Threshold of Hope

Books by John Paul II

Crossing the Threshold of Hope. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

The Encyclicals of John Paul II. Edited by J. Michael Miller. Huntington, Ind.: Our Sunday Visitor, 1996.

The Place Within: The Poetry of Pope John Paul II. New York: Random House, 1994.

The Wisdom of John Paul II: The Pope on Life’s Most Vital Questions. New York: Vintage Books, 2001.

Books about John Paul II

Cornwell, John. Breaking the Faith: The Pope, the People, and the Fate of Catholicism. New York: Viking Press, 2001.

Sherwin, Byron L., and Harold Kasimow, eds. John Paul II and Interreligious Dialogue. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1999.

Shivanandan, Mary. Crossing the Threshold of Love: A New Vision of Marriage in the Light of John Paul II’s Anthropology. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press of America, 1999.

Willey, David. God’s Politician: Pope John Paul II, the Catholic Church, and the New World Order. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Other Resources

Web site: www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/index.htm. Official Vatican web site on John Paul II.

“The first and fundamental structure for a ‘human ecology’ is the family.”

(1931–)

• • • • • • •

Born Richard Alpert to middleclass Jewish parents, Ram Dass is an iconic teacher of Eastern religious traditions, especially as they are practiced in the West. He is widely credited with imparting Eastern religious philosophy and the practice of yoga to the generation of spiritually hungry young Americans that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s.

Born in Boston, Alpert earned a Ph.D. in psychology from Stanford University and by the late 1950s was one of the youngest tenured professors at Harvard University. But the direction of his life changed forever when Timothy Leary, a Harvard colleague, introduced Alpert to psilocybin and other hallucinogens. They saw drugs as a means of mind expansion and publicized their views widely. Alpert, in particular, equated his drug-induced trips with a kind of religious experience. He later wrote that while high on psilocybin he came to recognize the difference between his ego and what he called “that which was I beyond Life and Death.” Still later he dubbed this the “soul nature” and taught others to find it through meditation and study.

Ram Dass came to recognize the difference between his ego and what he called “that which was I beyond Life and Death.” He dubbed this the “soul nature” and taught others to find it through meditation and study.

In 1963, as an experiment, Leary and Alpert administered psychedelic drugs to some students and were subsequently fired by Harvard. This censure set Alpert on a spiritual quest. He was increasingly frustrated with “coming down” from the semireligious highs he felt with psychedelics and wanted something more permanent. In 1967 he went to India and met Neem Karoli Baba, a Hindu holy man who became his guru. Baba, known as Maharajji to his followers, renamed Alpert “Ram Dass,” which means “servant of God.”

Ram Dass returned to the United States and, in 1971, wrote his classic, Be Here Now. Part memoir, part meditation, the book describes his religious philosophy, combining Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and even some Christianity. It sold over 2 million copies and is often credited with launching the New Age movement. In subsequent years Ram Dass founded or helped found the Hanuman Foundation, which fosters spiritually directed social action in the West; the Prison Ashram Project, which teaches inmates spiritual values through service projects; the Seva Foundation, which promotes health care in developing nations, and the Dying Project, which attempts to instill spiritual meaning in end-of-life experiences.

In 1997 Ram Dass suffered a massive stroke that he said gave him a new understanding of suffering, patience, and acceptance of death. He called the stroke, which slurred his speech and put him in a wheelchair, a “gift” from Maharajji, who died in 1973. Three years after his stroke, he wrote Still Here: Embracing Aging, Changing, and Dying, in which he tried to guide readers to a spiritually rich maturity. Ram Dass continues to write, lecture, and teach around the world.

HIS WORDS

This is the place of pure being. That inner place where you dwell, you just be. There is nothing to be done in that place. From that place, then, it all happens, it manifests in perfect harmony with the universe. Because you are the laws of the universe. You are the laws of the universe! This is what man’s journey into consciousness is all about. This is Om (home). It’s going Om, this is the place! Becoming one with God, returning. It’s the return to the roots that the Tao talks about.… It’s Buddha consciousness, it’s Christ consciousness. Jesus says: I and my Father are One. When Buddha says: You give up attachment and you finish with the illusion. This is the place!”

—Be Here Now, pp. 85–87

Books by Ram Dass

Be Here Now. San Cristobol, N.M.: Lama Foundation, 1971, distributed by Crown Publishing, New York, 1971.

Grist for the Mill. With Stephen Levine. Santa Cruz, Calif.: Unity Press, 1977.

How Can I Help? Stories and Reflections on Service. With Paul Gorman. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Journey of Awakening: A Meditator’s Guidebook. New York: Bantam Books, 1990.

The Meditative Mind: Varieties of Meditative Experience. With Daniel P. Goleman. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher, 1996.

Miracle of Love: Stories about Neem Karoli Baba. New York: Button Books, 1979.

The Only Dance There Is: Talks Given at the Menninger Foundation. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press, 1974.

The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. As Richard Alpert, with Timothy Leary and Ralph Metzner. New Hyde Park, N.Y.: University Books, 1964.

Still Here: Embracing Aging, Changing, and Dying. New York: Riverhead Books, 2000.

Organizations

Human Kindness Foundation (Prison Ashram Project), P.O. Box 61619, Durham, NC 27715; phone: 919-304-2220; web site: www.humankindness.org.

Seva Foundation, 1786 Fifth St., Berkeley, CA 94710; phone: 800-223-7382; web site: www.seva.org.

Other Resources

Web site: www.ramdasstapes.org. The Ram Dass Tape Library Foundation’s nonprofit web site offering tapes of Ram Dass’s lectures with updates about his health and speaking schedule.

Videotapes: Evolution of a Yogi. Hartley Film Foundation, 1970; Fierce Grace, Lemle Pictures, 2001; available at lemlepix@worldnet.att.net.

Audiotape: Promises and Pitfalls of the Spiritual Path, Hanuman Foundation Tape Library, 1988.

“This is Om (home). It’s going Om, this is the place! Becoming one with God, returning.”

(1861–1941)

• • • • • • •

The great Hindu poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore was the first Asian writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. Through the popular medium of verse, Tagore conveyed to the world the beauty of India’s mystical ideal of divine love, with its poignant echoes in the realm of human love. He became the voice of India’s sacred and artistic heritage, and through him the fundamental values of Indian culture became more widely known outside of his homeland—despite the fact that only a fraction of his vast output has been translated from his native Bengali into other languages. The spread of these values—peace, tolerance, and unity—contributed to the century’s movement toward a new world culture founded on diversity and universality.

Tagore was born in Calcutta to a celebrated Brahmin family; his father, Debendranath Tagore, was a mystic and a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious reform movement. Although Rabindranath was also a playwright, novelist, and author of short stories and essays, he is chiefly known for his lyrical poetry, influenced by the love poems of the Bengali Vaishnavas (worshipers of Lord Vishnu), the mystical songs of the tantric Baul sect of Bengal, and the medieval North Indian poet-saint Kabir. Tagore’s Gitanjali (Song Offerings), published in 1912 in England and the United States, was his first English translation of his own work. Championed by famous poets of the day, including W. B. Yeats and Ezra Pound, it won him the 1913 Nobel Prize. Yeats wrote in his introduction to the published work that Gitanjali “stirred my blood as nothing has for years.” Tagore was knighted in 1915 but gave up the title in 1919 in protest against the infamous Amritsar massacre of four hundred Indian demonstrators by British troops. His poetry in English enjoyed great popularity in the West, and in 1930 he went on a world tour that included meetings with Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Frost, and other eminent people of the day.

Tagore’s reputation in Bengal to this day is akin to that of Shakespeare in the English-speaking world. He is the only person ever to author the national anthems of two different nations: Bangladesh and India.

Tagore’s verse reflects his belief in the oneness of God, nature, and humanity—a concept he wrote about directly in books such as Sadhana, Creative Unity, and The Religion of Man. Among his bestknown works are The Gardener, The Crescent Moon, his translation Songs of Kabir, Cycle of Spring, Fireflies, Sheaves, and the plays The Post Office and Chitra. He was also a much-admired painter and a composer of songs as well as a reformer and critic of colonialism, nationalism, and the Indian caste system. Shantiniketan (Abode of Peace), a school he founded in Bolpur in 1901, was inspired by traditional Hindu ideals of education; in 1921 it became the internationally attended Visva-Bharati University. In the 1960s some of Tagore’s hauntingly beautiful fiction was brought to the screen by the internationally known Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray.

HIS WORDS

That I want thee, only thee—let my heart repeat without end. All desires that distract me, day and night, are false and empty to the core.

As the night keeps hidden in its gloom the petition for light, even thus in the depth of my unconsciousness rings the cry—I want thee, only thee.

As the storm still seeks its end in peace when it strikes against peace with all its might, even thus my rebellion strikes against thy love and still its cry is—I want thee, only thee.

—Gitanjali, vol. 38

The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures.

It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers.

It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and death, in ebb and in flow.

I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages dancing in my blood this moment.

—Gitanjali, vol. 69

Books by Rabindranath Tagore

Gitanjali: A Collection of Indian Songs. Introduction by W. B. Yeats. 1912. Reprint, New York: Dover, 2000. Prose versions translated by the author from the original Bengali.

Reminiscences. 1917. Reprint, Madras: Macmillan India, 1987.

Selected Poems. Translated by William Radice. New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

Selected Short Stories. Translated by William Radice. New York: Penguin Books, 1994.

Songs of Kabir. Translated by Rabindranath Tagore. 1915. Reprint, York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1995.

A Tagore Reader. Edited by Amiya Chakravarty. Boston: Beacon Press, 1971.

Books about Rabindranath Tagore

Dutta, Krishna, and Andrew Robinson. Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man. London: Bloomsbury, 1997.

Hudson, Yeager. Emerson and Tagore: The Poet as Philosopher (Asia and the Wider World Series, vol. 1). South Bend, Ind.: Cross Cultural Publications, 1988.

Other Resources

Films/Videotape: Two Daughters, directed by Satyajit Ray, 1961, available on videotape; The Home and the World, directed by Satyajit Ray, 1984.

Audiotape: The Crescent Moon: Prose Poems, narrated by Deepak Chopra, Amber-Allen, 1996.

“The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures.”

(1863–1902)

• • • • • • •

Swami Vivekananda became the first teacher from the Hindu tradition to bring to a large Western audience the teachings of Vedanta, a philosophy of the divine nature of all things, based on the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita, and other Indian scriptures.

As a child named Narendranath Datta, Vivekananda was fascinated by the wandering monks who were a regular feature of the Indian countryside, and he would sometimes try to imitate their meditation. He was a bright student in school and university, specializing in Western philosophy and logic, and he came to be very skeptical about the Hindu beliefs in which he had been raised, placing his faith solely in reason and logic. Then he met the God-intoxicated sage Ramakrishna, and everything changed for him. Ramakrishna was no intellectual, yet he radiated an atmosphere Vivekananda had never experienced before, and the young skeptic’s faith was restored. Vivekananda was convinced beyond any doubt that God-realization is the most important thing in life, and he became one of Ramakrishna’s disciples.

After Ramakrishna’s death in 1886, Vivekananda decided it was necessary to take Vedanta to the West—a revolutionary idea at the time. In 1893 he traveled to the United States to be present at the first Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, where his teaching generated great interest—and some commotion among conservative Christians. The New York Herald called him “undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him, we feel foolish to send missionaries to this learned nation.” Following the parliament, Vivekananda traveled throughout the United States and England for four years, lecturing and teaching. A number of his talks were recorded and collected into books.

Vivekananda’s teaching formed the foundation for the much larger Western interest in Hindu philosophy that arose in the second half of the twentieth century.

Vivekananda spent the rest of his relatively brief life in India, where he founded the Ramakrishna Mission and Order and began a series of educational, philanthropic, and health-care concerns aimed at improving material and spiritual conditions among his countrymen. He was able to make one further teaching trip to the United States in 1899 and died at the age of thirty-nine. His Ramakrishna Order continues to flourish both inside and outside India, and his teaching formed the foundation for the much larger Western interest in Hindu philosophy that arose in the second half of the twentieth century.

HIS WORDS

This is the gist of all worship—to be pure and to do good to others. He who sees Śiva in the poor, in the weak, and in the diseased, really worships Śiva and if he sees Śiva only in the image, his worship is but preliminary He who has served and helped one poor man seeing Śiva in him, without thinking of his caste, creed, or race, or anything, with him Śiva is more pleased than with the man who sees Him only in temples.

—The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, vol. 3, p. 141

It is impossible to find God outside of ourselves. Our own souls contribute all of the divinity that is outside of us. We are the greatest temple. The objectification is only a faint imitation of what we see within ourselves.

—The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, vol. 7, p. 59

Books by Swami Vivekananda

The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1985.

Jnana-Yoga. New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1980.

Karma-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga. New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1980.

Living at the Source: Yoga Teachings of Vivekananda. Edited by Ann Myren and Dorothy Madison. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1996.

Raja-Yoga. New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1980.

Books about Swami Vivekananda

Chetanananda, Swami. Vivekananda: East Meets West: A Pictorial Biography. St. Louis: Vedanta Society, 1995.

Nikhilananda, Swami. Vivekananda: A Biography. New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1989.

Organization

Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York, 17 East Ninety-fourth St., New York, NY 10128-0611; phone: 212-534-9445; fax: 212-828-1618; e-mail: rvcnewyork@worldnet.att.net; web site: www.ramakrishna.org.

“We are responsible for what we are, and whatever we wish ourselves to be, we have the power to make ourselves.”