Forests are complex ecological systems in which trees are the dominant life-form. Together, forests of all types cover nearly 30 percent of Earth’s land surface. Tree-dominated forests can occur wherever the temperatures rise above 10°C (50°F) in the warmest months and the annual precipitation is more than 200 mm (8 inches). They can develop under a variety of conditions within these climatic limits, and the kind of soil, plant, and animal life differs according to the extremes of environmental influences. In cool, high-latitude subpolar regions, forests are dominated by hardy conifers like pines, spruces, and larches. These taiga (boreal) forests have prolonged winters and between 250 and 500 mm (10 and 20 inches) of rainfall annually.

Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), such as this grazer looking for grass near Torinen, Sweden, are well adapted for life in taiga forests in northern Europe and Asia. Olivier Morin/AFP/Getty Images

In more temperate high-latitude climates, mixed forests of both conifers and broad-leaved deciduous trees predominate. Broad-leaved deciduous forests develop in middle-latitude climates, where there is an average temperature above 10 °C (50 °F) for at least six months every year and annual precipitation is above 400 mm (16 inches). A growing period of 100 to 200 days allows deciduous forests to be dominated by oaks, elms, birches, maples, beeches, and aspens. In the humid climates of the equatorial belt, tropical rainforests develop. There heavy rainfall supports evergreens that have broad leaves instead of needle leaves, as in cooler forests. In the lower latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, the temperate deciduous forest reappears.

Forest types are distinguished from each other according to species composition (which develops in part according to the age of the forest), the density of tree cover, types of soils found there, and the geologic history of the forest region.

Mixed evergreen and hardwood forest on the slopes of the Adirondack Mountains near Keene Valley, New York. Jerome Wyckoff

Soil conditions are distinguished according to depth, fertility, and the presence of perennial roots. Soil depth is important because it determines the extent to which roots can penetrate into the earth and, therefore, the amount of water and nutrients available to the trees. The soil of taiga forests is sandy and quickly drained. Deciduous forests have brown soil, richer than sand in nutrients, and less porous. Rainforests and savanna woodlands have a soil layer rich in iron or aluminum, which give the soils either a reddish or yellowish cast. The amount of water available to the soil, and therefore available for tree growth, depends on the amount of annual rainfall. Water may be lost by evaporation from the surface or by leaf transpiration. Evaporation and transpiration also control the temperature of the air in forests, which is always slightly warmer in cold months and cooler in warm months than the air in surrounding regions.

The density of tree cover influences the amount of both sunlight and rainfall reaching every forest layer. A full-canopied forest absorbs between 60 and 90 percent of available light, most of which is absorbed by the leaves for photosynthesis. The movement of rainfall into the forest is considerably influenced by leaf cover, which tends to slow the velocity of falling water, which penetrates down to the ground level by running down tree trunks or dripping from leaves. Water not absorbed by the tree roots for nutrition runs along root channels, so water erosion is therefore not a major factor in shaping forest topography.

Forests are among the most complex ecosystems in the world, and they exhibit extensive vertical stratification. Conifer forests have the simplest structure: a tree layer rising to about 30 metres (98 feet), a shrub layer that is spotty or even absent, and a ground layer covered with lichens, mosses, and liverworts. Deciduous forests are more complex; the tree canopy is divided into an upper and lower story, while rainforest canopies are divided into at least three strata. The forest floor in both of these forests consists of a layer of organic matter overlying mineral soil. The humus layer of tropical soils is affected by the high levels of heat and humidity, which quickly decompose whatever organic matter exists. Fungi on the soil surface play an important role in the availability and distribution of nutrients, particularly in the northern coniferous forests. Some species of fungi live in partnership with the tree roots, while others are parasitically destructive.

Animals that live in forests have highly developed hearing, and many are adapted for vertical movement through the environment. Because food other than ground plants is scarce, many ground-dwelling animals use forests only for shelter. In temperate forests, birds distribute plant seeds and insects aid in pollination, along with the wind. In tropical forests, fruit bats and birds effect pollination. The forest is nature’s most efficient ecosystem, with a high rate of photosynthesis affecting both plant and animal systems in a series of complex organic relationships.

A rainforest is a luxuriant forest, generally composed of tall, broad-leaved trees and usually found in wet tropical uplands and lowlands around the Equator.

Rainforests usually occur in regions where there is a high annual rainfall of generally more than 1,800 mm (70 inches) and a hot and steamy climate. The trees found in these regions are evergreen. Rainforests may also be found in areas of the tropics in which a dry season occurs, such as the “dry rainforests” of northeastern Australia. In these regions annual rainfall is between 800 and 1,800 mm (31 and 70 inches) and as many as 75 percent of the trees are deciduous.

Tropical rainforests are found primarily in South and Central America, West and Central Africa, Indonesia, parts of Southeast Asia, and tropical Australia. The climate in these regions is one of relatively high humidity with no marked seasonal variation. Temperatures remain high, usually about 30 °C (86 °F) during the day and 20 °C (68 °F) at night. Where altitude increases along the borders of equatorial rainforests, the vegetation is replaced by montane forests, as in the highlands of New Guinea, the Gotel Mountains of Cameroon, and in the Ruwenzori mass of Central Africa. Tropical deciduous forests are located mainly in eastern Brazil, southeastern Africa, northern Australia, and parts of Southeast Asia.

Other kinds of rainforests include the monsoon forests, most like the popular image of jungles, with a marked dry season and a vegetation dominated by deciduous trees such as teak, thickets of bamboo, and a dense undergrowth. Mangrove forests occur along estuaries and deltas on tropical coasts. Temperate rainforests filled with evergreen and laurel trees are lower and less dense than other kinds of rainforests because the climate is more equable, with a moderate temperature range and well-distributed annual rainfall.

The topography of rainforests varies considerably, from flat lowland plains marked by small rock hills to highland valleys crisscrossed by streams. Volcanoes that produce rich soils are fairly common in the humid tropical forests.

Soil conditions vary with location and climate, although most rainforest soils tend to be permanently moist and soggy. The presence of iron gives the soils a reddish or yellowish colour and develops them into two types of soils: extremely porous tropical red loams, which can be easily tilled; and lateritic soils, which occur in well-marked layers that are rich in different minerals. Chemical weathering of rock and soil in the equatorial forests is intense, and in rainforests weathering produces soil mantles up to 100 metres (330 feet) deep. Although these soils are rich in aluminum, iron oxides, hydroxides, and kaolinite, other minerals are washed out of the soil by leaching and erosion. The soils are not very fertile, either, because the hot, humid weather causes organic matter to decompose rapidly and to be quickly absorbed by tree roots and fungi.

Rainforests exhibit a highly vertical stratification in plant and animal development. The highest plant layer, or tree canopy, extends to heights between 30 and 50 metres (98 to 164 feet). Most of the trees are dicotyledons, with thick leathery leaves and shallow root systems. The nutritive, food-gathering roots are usually no more than a few centimetres deep. Rain falling on the forests drips down from the leaves and trickles down tree trunks to the ground, although a great deal of water is lost to leaf transpiration.

Most of the herbaceous food for animals is found among the leaves and branches of the canopy, where a variety of animals have developed swinging, climbing, gliding, and leaping movements to seek food and escape predators. Monkeys, flying squirrels, and sharp-clawed woodpeckers are some of the animals that inhabit the treetops. They rarely need to come down to ground level.

The next lowest layer of the rainforest is filled with small trees, lianas, and epiphytes, such as orchids, bromeliads, and ferns. Some of these are parasitic, strangling their host’s trunks; others use the trees simply for support.

Above the ground surface the space is occupied by tree branches, twigs, and foliage. Many species of animals run, flutter, hop, and climb in the undergrowth. Most of these animals live on insects and fruit, although a few are carnivorous. They tend to communicate more by sound than by sight in this dense forest strata.

Contrary to popular belief, the rainforest floor is not impassable. The ground surface is bare, except for a thin layer of humus and fallen leaves. The animals inhabiting this strata, such as rhinoceroses, chimpanzees, gorillas, elephants, deer, leopards, and bears, are adapted to walking and climbing short distances. Below the soil surface, burrowing animals, such as armadillos and caecilians, are found, as are microorganisms that help decompose and free much of the organic litter accumulated by other plants and animals from all strata.

The climate of the ground layer is unusually stable. The upper stories of tree canopies and the lower branches filter sunlight and heat radiation, as well as reduce wind speeds, so that the temperatures remain fairly even throughout the day and night.

Virtually every group of animals except fishes is represented in the rainforest ecosystem. Many invertebrates are very large, such as giant snails and butterflies. The breeding seasons for most animals tend to be coordinated with the availability of food, which, although generally abundant, does vary seasonally from region to region. Climatic variations, however, are slight and thus affect animal behaviour very little. Those animals that do not have highly developed modes of quick locomotion are concealed from predators by camouflage or become nocturnal feeders.

Although similar to temperate rainforests, tropical rainforests are found in wet tropical uplands and lowlands around the Equator.

Rainforests are vegetation types dominated by broad-leaved trees that form a dense upper canopy (layer of foliage) and contain a diverse array of vegetation. Contrary to common thinking, not all rainforests occur in places with high, constant rainfall; for example, in the so-called “dry rainforests” of northeastern Australia the climate is punctuated by a dry season, which reduces the annual precipitation. Nor are all forests in areas that receive large amounts of rainfall true rainforests; the conifer-dominated forests in the extremely wet coastal areas of the American Pacific Northwest are temperate evergreen forest ecosystems. Therefore, to avoid conveying misleading climatic information, the term rainforest is now preferred over rain forest.

This section covers only the richest of rainforests—the tropical rainforests of the ever-wet tropics.

Tropical rainforests represent the oldest major vegetation type still present on the terrestrial Earth. Like all vegetation, however, that of the rainforest continues to evolve and change, so that modern tropical rainforests are not identical with rainforests of the geologic past.

Rainforest vegetation along the northern coast of Ecuador. © Victor Englebert

Tropical rainforests grow mainly in three regions: the Malesian botanical subkingdom, which extends from Myanmar (Burma) to Fiji and includes the whole of Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu and parts of Indochina and tropical Australia; tropical South and Central America, especially the Amazon basin; and West and Central Africa. Smaller areas of tropical rainforest occur elsewhere in the tropics wherever climate is suitable. The principal areas of tropical deciduous forest are in India, the Myanmar–Vietnam–southern coastal China region, and eastern Brazil, with smaller areas in South and Central America north of the Equator, the West Indies, southeastern Africa, and northern Australia.

The flowering plants (angiosperms) first evolved and diversified during the Cretaceous Period about 100 million years ago, during which time global climatic conditions were warmer and wetter than those of the present. The vegetation types that evolved were the first tropical rainforests, which blanketed most of the Earth’s land surfaces at that time. Only later—during the middle of the Paleogene Period, about 40 million years ago—did cooler, drier climates develop, leading to the development across large areas of other vegetation types.

It is no surprise, therefore, to find the greatest diversity of flowering plants today in the tropical rainforests where they first evolved. Of particular interest is the fact that the majority of flowering plants displaying the most primitive characteristics are found in rainforests (especially tropical rainforests) in parts of the Southern Hemisphere, particularly South America, northern Australia and adjacent regions of Southeast Asia, and some larger South Pacific islands. Of the 13 angiosperm families generally recognized as the most primitive, all but two—Magnoliaceae and Winteraceae—are overwhelmingly tropical in their present distribution. Three families—Illiciaceae, Magnoliaceae, and Schisandraceae—are found predominantly in Northern Hemisphere rainforests. Five families—Amborellaceae, Austrobaileyaceae, Degeneriaceae, Eupomatiaceae, and Himantandraceae—are restricted to rainforests in the tropical Australasian region. Members of the Winteraceae are shared between this latter region and South America; those of the Lactoridaceae grow only on the southeast Pacific islands of Juan Fernández; members of the Canellaceae are shared between South America and Africa; and two families—Annonaceae and Myristicaceae—generally occur in tropical regions. This has led some authorities to suggest that the original cradle of angiosperm evolution might lie in Gondwanaland, a supercontinent of the Southern Hemisphere thought to have existed in the Mesozoic Era (251 to 65.5 million years ago) that consisted of Africa, South America, Australia, peninsular India, and Antarctica. An alternative explanation for this geographic pattern is that in the Southern Hemisphere, especially on islands, there are more refugia—that is, isolated areas whose climates remained unaltered while those of the surrounding areas changed, enabling archaic life-forms to persist.

The first angiosperms are thought to have been massive, woody plants appropriate for a rainforest habitat. Most of the smaller, more delicate plants that are so widespread in the world today evolved later, ultimately from tropical rainforest ancestors. While it is possible that even earlier forms existed that await discovery, the oldest angiosperm fossils—leaves, wood, fruits, and flowers derived from trees—support the view that the earliest angiosperms were rainforest trees. Further evidence comes from the growth forms of the most primitive surviving angiosperms: all 13 of the most primitive angiosperm families consist of woody plants, most of which are large trees.

As the world climate cooled in the middle of the Cenozoic, it also became drier. This is because cooler temperatures led to a reduction in the rate of evaporation of water from, in particular, the surface of the oceans, which led in turn to less cloud formation and less precipitation. The entire hydrologic cycle slowed, and tropical rainforests—which depend on both warmth and consistently high rainfall—became increasingly restricted to equatorial latitudes. Within those regions rainforests were limited further to coastal and hilly areas where abundant rain still fell at all seasons. In the middle latitudes of both hemispheres, belts of atmospheric high pressure developed. Within these belts, especially in continental interiors, deserts formed. In regions lying between the wet tropics and the deserts, climatic zones developed in which rainfall adequate for luxuriant plant growth was experienced for only a part of the year. In these areas new plant forms evolved from tropical rainforest ancestors to cope with seasonally dry weather, forming tropical deciduous forests. In the drier and more fire-prone places, savannas and tropical grasslands developed.

Retreat of the rainforests was particularly rapid during the period beginning 5 million years ago leading up to and including the Pleistocene Ice Ages, or glacial intervals, that occurred between 2.6 million and 11,700 years ago. Climates fluctuated throughout this time, forcing vegetation in all parts of the world to repeatedly migrate, by seed dispersal, to reach areas of suitable climate. Not all plants were able to do this equally well because some had less-effective means of seed dispersal than others. Many extinctions resulted. During the most extreme periods (the glacial maxima, when climates were at their coldest and, in most places, also driest), the range of tropical rainforests shrank to its smallest extent, becoming restricted to relatively small refugia. Alternating intervals of climatic amelioration led to repeated range expansion, most recently from the close of the last glacial period about 10,000 years ago. Today large areas of tropical rainforest, such as Amazonia, have developed as a result of this relatively recent expansion. Within them it is possible to recognize “hot spots” of plant and animal diversity that have been interpreted as glacial refugia.

Tropical rainforests today represent a treasure trove of biological heritage. They not only retain many primitive plant and animal species but also are communities that exhibit unparalleled biodiversity and a great variety of ecological interactions. The tropical rainforest of Africa was the habitat in which the ancestors of humans evolved, and it is where the nearest surviving human relatives—chimpanzees and gorillas—live still. Tropical rainforests supplied a rich variety of food and other resources to indigenous peoples, who, for the most part, exploited this bounty without degrading the vegetation or reducing its range to any significant degree. However, in some regions a long history of forest burning by the inhabitants is thought to have caused extensive replacement of tropical rainforest and tropical deciduous forest with savanna.

Not until the past century, however, has widespread destruction of tropical forests occurred. Regrettably, tropical rainforests and tropical deciduous forests are now being destroyed at a rapid rate in order to provide resources such as timber and to create land that can be used for other purposes, such as cattle grazing. Today tropical forests, more than any other ecosystem, are experiencing habitat alteration and species extinction on a greater scale and at a more rapid pace than at any time in their history—at least since the major extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, some 65.5 million years ago.

The equatorial latitude of tropical rainforests and tropical deciduous forests keeps day length and mean temperature fairly constant throughout the year. The sun rises daily to a near-vertical position at noon, ensuring a high level of incoming radiant energy at all seasons. Although there is no cold season during which plants experience unfavourable temperatures that prohibit growth, there are many local variations in climate that result from topography, and these variations influence and restrict rainforest distribution within the tropics.

Tropical rainforests occur in regions of the tropics where temperatures are always high and where rainfall exceeds about 1,800 to 2,500 mm (about 70 to 100 inches) annually and occurs fairly evenly throughout the year. Similar hot climates in which annual rainfall lies between about 800 and 1,800 mm and in which a pronounced season of low rainfall occurs typically support tropical deciduous forests—that is, rainforests in which up to about three-quarters of the trees lose their leaves in the dry season. The principal determining climatic factor for the distribution of rainforests in lowland regions of the tropics, therefore, is rainfall, both the total amount and the seasonal variation. Soil, human disturbance, and other factors also can be important controlling influences.

The climate is always hot and wet in most parts of the equatorial belt, but in regions to its north and south seasonal rainfall is experienced. During the summer months of the Northern Hemisphere—June to August—weather systems shift northward, bringing rain to regions in the northern parts of the tropics, as do the monsoon rains of India and Myanmar. Conversely, during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, weather systems move southward, bringing rain from December to February to places such as northern Australia. In these hot, seasonally wet areas grow tropical deciduous forests, such as the teak forests of Myanmar and Thailand. In other locations where conditions are similar but rainfall is not so reliable or burning has been a factor, savannas are found.

Topographic factors influence rainfall and consequently affect rainforest distribution within a region. For example, coastal regions where prevailing winds blow onshore are likely to have a wetter climate than coasts that experience primarily offshore winds. The west coasts of tropical Australia and South America south of the Equator experience offshore winds, and these dry regions can support rainforests only in very small areas. This contrasts with the more extensively rainforest-clad, east-facing coasts of these same continents at the same latitudes. The same phenomenon is apparent on a smaller scale where the orientation of coastlines is parallel to, rather than perpendicular to, wind direction. For example, in the Townsville area of northeastern Australia and in Benin in West Africa, gaps in otherwise fairly continuous tracts of tropical rainforest occur where the prevailing winds blow along the coast rather than across it.

Mean temperatures in tropical rainforest regions are between 20 and 29 °C (68 and 84 °F), and in no month is the mean temperature below 18 °C (64 °F). Temperatures become critical with increasing altitude; in the wet tropics temperatures fall by about 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) for every 100 metres (328 feet) climbed. Vegetation change across altitudinal gradients tends to be gradual and variable and is interpreted variously by different authorities. For example, in Uganda tropical rainforest grows to an altitude of 1,100 to 1,300 metres (3,600 to 4,300 feet) and has been described as giving way, via a transition forest zone, to montane rainforest above 1,650 to 1,750 metres (5,400 to 5,700 feet), which continues to 2,300 to 3,400 metres (7,500 to 11,200 feet). In New Guinea, lowland tropical rainforest reaches 1,000 to 1,200 metres (3,300 to 3,900 feet), above which montane rainforests extend, with altitudinal variation, to 3,900 metres (12,800 feet). In Peru, lowland rainforest extends upward to 1,200 to 1,500 metres (3,900 to 4,900 feet), with transitional forest giving way to montane rainforest above 1,800 to 2,000 metres (5,900 to 6,600 feet), which continues to 3,400 to 4,000 metres (11,200 to 13,100 feet). These limits are comparable and reflect the similarities of climate in all regions where tropical rainforests occur. Plant species, however, are often quite different among regions.

Although the climate supporting tropical rainforests is perpetually hot, temperatures never reach the high values regularly recorded in drier places to the north and south of the equatorial belt. This is partly due to high levels of cloud cover, which limit the mean number of sunshine hours per day to between four and six. In hilly areas where air masses rise and cool because of the topography, the hours of sunlight may be even fewer. Nevertheless, the heat may seem extreme owing to the high levels of atmospheric humidity, which usually exceed 50 percent by day and approach 100 percent at night. Exacerbating the discomfort is the fact that winds are usually light; mean wind speeds are generally less than 10 km (6.2 miles) per hour and less than 5 km (3.1 miles) per hour in many areas. Devastating hurricanes (cyclones and typhoons) occur periodically in some coastal regions toward the margins of the equatorial belt, such as in the West Indies and in parts of the western Pacific region. Although relatively infrequent, such storms have an important effect on forest structure and regeneration.

The climate within any vegetation (microclimate) is moderated by the presence of plant parts that reduce incoming solar radiation and circulation of air. This is particularly true in tropical rainforests, which are structurally more dense and complex than other vegetation. Within the forest, temperature range and wind speed are reduced and humidity is increased relative to the climate above the tree canopy or in nearby clearings. The amount of rain reaching the ground is also reduced—by as much as 90 percent in some cases—as rainwater is absorbed by epiphytes (plants that grow on the surface of other plants but that derive nutrients and water from the air) and by tree bark or is caught by foliage and evaporates directly back to the atmosphere.

Soils in tropical rainforests are typically deep but not very fertile, partly because large proportions of some mineral nutrients are bound up at any one time within the vegetation itself rather than free in the soil. The moist, hot climatic conditions lead to deep weathering of rock and the development of deep, typically reddish soil profiles rich in insoluble sesquioxides of iron and aluminum, commonly referred to as tropical red earths. Because precipitation in tropical rainforest regions exceeds evapotranspiration at almost all times, a nearly permanent surplus of water exists in the soil and moves downward through the soil into streams and rivers in valley floors. Through this process nutrients are leached out of the soil, leaving it relatively infertile. Most roots, including those of trees, are concentrated in the uppermost soil layers where nutrients become available from the decomposition of fallen dead leaves and other organic litter. Sandy soils, particularly, become thoroughly leached of nutrients and support stunted rainforests of peculiar composition. A high proportion of plants in this environment have small leaves that contain high levels of toxic or unpalatable substances. A variant of the tropical rainforest, the mangrove forest, is found along estuaries and on sheltered sea coasts in tidally inundated, muddy soils.

Epiphytic orchids (Dendrobium). E.R. Degginger

Even within the same area, however, there are likely to be significant variations in soil related to topographic position and to bedrock differences, and these variations are reflected in forest composition and structure. For example, as altitude increases—even within the same area and on the same bedrock—soil depth decreases markedly and its organic content increases in association with changes in forest composition and structure.

Only a minority of plant and animal species in tropical rainforests and tropical deciduous forests have been described formally and named. Therefore, only a rough estimate can be given of the total number of species contained in these ecosystems, as well as the number that are becoming extinct as a result of forest clearance. Nevertheless, it is quite clear that these vegetation types are the most diverse of all, containing more species than any other ecosystem. This is particularly so in regions in which tropical rainforests not only are widespread but also are separated into many small areas by geographic barriers, as in the island-studded Indonesian region. In this area different but related species often are found throughout various groups of islands, adding to the total regional diversity. Exceptionally large numbers of species also occur in areas of diverse habitat, such as in topographically or geologically complex regions and in places that are believed to have acted as refugia throughout the climatic fluctuations of the past few million years. According to some informed estimates, more than a hundred species of rainforest fauna and flora become extinct every week as a result of widespread clearing of forests by humans. Insects are believed to constitute the greatest percentage of disappearing species.

All major groups of terrestrial organisms are represented abundantly in tropical rainforests. Among the higher plants, angiosperms are particularly diverse and include many primitive forms and many families not found in the vegetation of other ecosystem types. Many flowering plants are large trees, of which there is an unparalleled diversity. For example, in one area of 23 hectares (57 acres) in Malaysia, 375 different tree species with trunk diameters greater than 91 cm (35.8 inches) have been recorded, and in a 50-hectare (124-acre) area in Panama, 7,614 trees belonging to 186 species had trunk diameters greater than 20 cm (7.8 inches). New species of plants—even those as conspicuously large as trees—are found every year. Relatively few gymnosperms (conifers and their relatives), however, are found in rainforests; instead, they occur more frequently at the drier and cooler extremes of the range of climates in which tropical rainforests grow. Some plant families, such as Arecaceae (palms), are typically abundant in all tropical rainforest regions, although different species occur from region to region. Other families are more restricted geographically. The family Dipterocarpaceae (dipterocarps) includes many massive trees that are among the most abundant and valuable species in the majority of tropical rainforests in western Malesia; the family, however, is uncommon in New Guinea and Africa and absent from South and Central America and Australia. The Bromeliaceae (bromeliads), a large family consisting mainly of rainforest epiphytes and to which the pineapple belongs, is entirely restricted to the New World.

Tropical rainforests, which contain many different types of trees, seldom are dominated by a single species. A species can predominate, however, if particular soil conditions favour this occurrence or minimal disturbance occurs for several tree generations. Tropical deciduous forests are less diverse and often are dominated by only one or two tree species. The extensive deciduous forests of Myanmar, for example, cover wide areas and are dominated by only one or two tree species—teak (Tectona grandis) and the smaller leguminous tree Xylia xylocarpa. In Thailand and Indochina deciduous forests are dominated by members of the Dipterocarpaceae family, Dipterocarpus tuberculatus, Pentacme suavis, and Shorea obtusa.

Ferns, mosses, liverworts, lichens, and algae are also abundant and diverse, although not as well studied and cataloged as the higher plants. Many are epiphytic and are found attached to the stems and sometimes the leaves of larger plants, especially in the wettest and most humid places. Fungi and other saprophytic plants (vegetation growing on dead or decaying matter) are similarly diverse. Some perform a vital role in decomposing dead organic matter on the forest floor and thereby releasing mineral nutrients, which then become available to roots in the surface layers of the soil. Other fungi enter into symbiotic relationships with tree roots (mycorrhizae).

Interacting with and dependent upon this vast array of plants are similarly numerous animals. Like the plants, most animal species are limited to only one or a few types of tropical rainforest within an area, with the result that the overall number of species is substantially greater than it is in a single forest type. For example, a study of insects in the canopy of four different types of tropical rainforest in Brazil revealed 1,080 species of beetle, of which 83 percent were found in only one forest type, 14 percent in two, and only 3 percent in three or four types. While the larger, more conspicuous vertebrates (mammals, birds, and to a lesser degree amphibians and reptiles) are well known, only a small minority of the far more diverse invertebrates (particularly insects) have ever been collected, let alone described and named.

As with the plants, some animal groups occur in all tropical rainforest regions. A variety of fruit-eating parrots, pigeons, and seed-eating weevil beetles, for example, can be expected to occur in any tropical rainforest. Other groups are more restricted. Monkeys, while typical of tropical rainforests in both the New and the Old World, are entirely absent from New Guinea and areas to its east and south. Tree kangaroos inhabit tropical rainforest canopies only in Australia and New Guinea, and birds of paradise are restricted to the same areas.

To a large extent these geographic variations in tropical rainforest biota reflect the long-term geologic histories of these ancient ecosystems. This is most clearly demonstrated in the Malesian phytogeographic subkingdom, which has existed as a single entity only since continental movements brought Australia and New Guinea northward into juxtaposition with Southeast Asia about 15 million years ago. Before that time the two parts were separated by a wide expanse of ocean and experienced separate evolution of their biota. Only a relatively small sea gap lies between them today; Java, Bali, and Borneo are on one side, and Timor and New Guinea are on the other, with islands such as Celebes and the Moluccas forming an intermediate region between. The gap is marked by a change in flora and, especially, fauna and is known as Wallace’s Line. The contrast is particularly stark with respect to mammals. To the west the rainforests are populated—or were populated until recently—by monkeys, deer, pigs, cats, elephants, and rhinoceroses, while those to the east have marsupial mammals, including opossums, cuscuses, dasyurids, tree kangaroos, and bandicoots. Only a few groups such as bats and rodents have migrated across the line to become common in both areas. Similar contrasts, albeit less pronounced, can be seen in many other animal and plant groups across the same divide.

Tropical rainforests are distinguished not only by a remarkable richness of biota but also by the complexity of the interrelationships of all the plant and animal inhabitants that have been evolving together throughout many millions of years. As in all ecosystems, but particularly in the complex tropical rainforest community, the removal of one species threatens the survival of others with which it interacts. Some interactions are mentioned below, but many have yet to be revealed.

Plants with similar stature and life-form can be grouped into categories called synusiae, which make up distinct layers of vegetation. In tropical rainforests the synusiae are more numerous than in other ecosystem types. They include not only mechanically independent forms, whose stems are self-supporting, and saprophytic plants but also mechanically dependent synusiae such as climbers, stranglers, epiphytes, and parasitic plants. An unusual mix of trees of different sizes is found in the tropical rainforest, and those trees form several canopies below the uppermost layer, although they are not always recognizably separate layers. The upper canopy of the tropical rainforest is typically greater than 40 metres (131 feet) above ground.

The tropical rainforest is structurally very complex. Its varied vegetation illustrates the intense competition for light that goes on in this environment in which other climatic factors are not limiting at any time of year and the vegetation is thus allowed to achieve an unequaled luxuriance and biomass. The amount of sunlight filtering through the many layers of foliage in a tropical rainforest is small; only about 1 percent of the light received at the top of the canopy reaches the ground. Most plants depend on light for their energy requirements, converting it into chemical energy in the form of carbohydrates by the process of photosynthesis in their chlorophyll-containing green tissues. Few plants can persist in the gloomy environment at ground level, and the surface is marked by a layer of rapidly decomposing dead leaves rather than of small herbaceous plants. Mosses grow on tree butts, and there are a few forbs such as ferns and gingers, but generally the ground is bare of living plants, and even shrubs are rare. However, tree seedlings and saplings are abundant; their straight stems reach toward the light but receive too little energy to grow tall enough before food reserves from their seeds are exhausted. Their chance to grow into maturity comes only if overhanging vegetation is at least partially removed through tree death or damage by wind. Such an occurrence permits more solar radiation to reach their level and initiates rapid growth and competition between saplings as to which will become a part of the well-lit canopy.

Gaps in the canopy of a tropical rainforest provide temporarily well-illuminated places at ground level and are vital to the regeneration of most of the forest’s constituent plants. Few plants in the forest can successfully regenerate in the deep shade of an unbroken canopy; many tree species are represented there only as a population of slender, slow-growing seedlings or saplings that have no chance of growing to the well-lit canopy unless a gap forms. Other species are present, invisibly, as dormant seeds in the soil. When a gap is created, seedlings and saplings accelerate their growth in the increased light and are joined by new seedlings sprouting from seeds stored in the soil that have been stimulated to germinate by light or by temperature fluctuations resulting from the sun’s shining directly on the soil surface. Other seeds arrive by various seed-dispersal processes. A thicket of regrowth rapidly develops, with the fastest-growing shrubs and trees quickly shading out opportunistic, light-demanding, low-growing herbaceous plants and becoming festooned with lianas. Through it all slower-growing, more shade-tolerant but longer-lived trees eventually emerge and restore the full forest canopy. The trees that initially fill in the gap in the canopy live approximately one century, whereas the slower-growing trees that ultimately replace them may live for 200 to 500 years or, in extreme cases, even longer. Detailed mapping of the trees in a tropical rainforest can reveal the locations of previous gaps through identification of clumps of the quicker-growing, more light-demanding species, which have yet to be replaced by trees in the final stage of successional recovery. Local, natural disturbances of this sort are vital to the maintenance of the full biotic diversity of the tropical rainforest.

Just as tropical rainforest plants compete intensely for light above ground, below ground they vie for mineral nutrients. The process of decomposition of dead materials is of crucial importance to the continued health of the forest because plants depend on rapid recycling of mineral nutrients. Bacteria and fungi are primarily responsible for this process. Some saprophytic flowering plants that occur in tropical rainforests rely on decomposing material for their energy requirements and in the process use and later release minerals. Some animals are important in the decomposition process; for example, in Malaysia termites have been shown to be responsible for the decomposition of as much as 16 percent of all litter, particularly wood. Most trees in the tropical rainforest form symbiotic mycorrhizal associations with fungi that grow in intimate contact with their roots; the fungi obtain energy from the tree and in turn provide the tree with phosphorus and other nutrients, which they absorb from the soil very efficiently. A mat of plant roots explores the humus beneath the rapidly decomposing surface layer of dead leaves and twigs, and even rotting logs are invaded by roots from below. Because nutrients are typically scarce at depth but, along with moisture, are readily available in surface layers, few roots penetrate very deeply into the soil. This shallow rooting pattern increases the likelihood of tree falls during storms, despite the support that many trees receive from flangelike plank buttresses growing radially outward from their trunk bases. When large trees fall, they may take with them other trees against which they collapse or to which they are tied by a web of lianas and thereby create gaps in the canopy.

An earthstar (Geastrum) puffball, growing on moist soil among mosses. Larry West—The National Audubon Society/Photo Researchers

Tree growth requires substantial energy investment in trunk development, which some plants avoid by depending on the stems of other plants for support. Perhaps the most obvious adaptation of this sort is seen in plants that climb from the ground to the uppermost canopy along other plants by using devices that resemble grapnel-like hooks. Lianas are climbers that are abundant and diverse in tropical rainforests; they are massive woody plants whose mature stems often loop through hundreds of metres of forest, sending shoots into new tree crowns as successive supporting trees die and decay. Climbing palms or rattans (Calamus) are prominent lianas in Asian rainforests, where the stems, which are used to make cane furniture, provide a valuable economic resource.

Lianas in a tropical rainforest. The vascular tissues of lianas are modified primarily for water conduction, which leaves these tall plants dependent on other plants for support. © Gary Braasch

Epiphytes are particularly diverse and include large plants such as orchids, aroids, bromeliads, and ferns in addition to smaller plants such as algae, mosses, and lichens. In tropical rainforests epiphytes are often so abundant that their weight fells trees. Epiphytes that grow near the upper canopy of the forest have access to bright sunlight but must survive without root contact with the soil. They depend on rain washing over them to provide water and mineral nutrients. During periods of drought, epiphytes undergo stress as water stored within their tissues becomes depleted. The diversity of epiphytes in tropical deciduous forests is much less than that of tropical rainforests because of the annual dry season.

Parasitic flowering plants also occur. Hemiparasitic mistletoes attached to tree branches extract water and minerals from their hosts but carry out their own photosynthesis. Plants that are completely parasitic also are found in tropical rainforests. Rafflesia, in Southeast Asia, parasitizes the roots of certain lianas and produces no aboveground parts until it flowers; its large orange and yellow blooms, nearly 1 metre (3.28 feet) in diameter, are the largest flowers of any plant.

Stranglers make up a type of synusia virtually restricted to tropical rainforests. In this group are strangler figs (Ficus), which begin life as epiphytes, growing from seeds left on high tree branches by birds or fruit bats. As they grow, they develop long roots that descend along the trunk of the host tree, eventually reaching the ground and entering the soil. Several roots usually do this, and they become grafted together as they crisscross each other to form a lattice, ultimately creating a nearly complete sheath around the trunk. The host tree’s canopy becomes shaded by the thick fig foliage, its trunk constricted by the surrounding root sheath and its own root system forced to compete with that of the strangling fig. The host tree is also much older than the strangler and eventually dies and rots away, leaving a giant fig “tree” whose apparent “trunk” is actually a cylinder of roots, full of large hollows that provide shelter and breeding sites for bats, birds, and other animals. Stranglers may also develop roots from their branches, which, when they touch the ground, grow into the soil, thicken, and become additional “trunks.” In this way stranglers grow outward to become large patches of fig forest that consist of a single plant with many interconnected trunks.

Some of the tallest trees and lianas, and the epiphytes they support, bear flowers and fruits at the top of the rainforest canopy, where the air moves unfettered by vegetation. They are able to depend on the wind for dispersal of pollen from flower to flower, as well as for the spreading of fruits and seeds away from the immediate environment of the parent plant. Ferns, mosses, and other lower plants also exploit the wind to carry their minute spores. However, a great many flowering plants, including many that grow in the nearly windless environment of the understory, depend on animals to perform these functions. They are as dependent on animals for reproductive success as the animals are on them for food—one example of the mutual dependence between plants and animals.

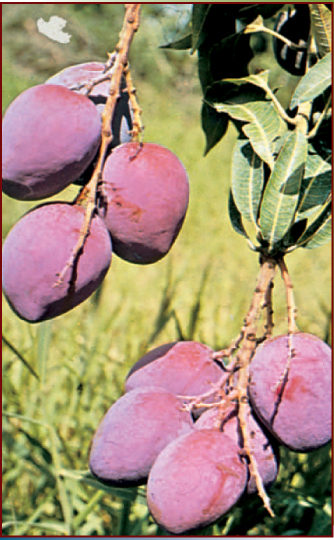

Many rainforest trees have sizable seeds from which large seedlings emerge and thrust their way through the thick mat of dead leaves on the dark forest floor. They develop tall stems, using food reserves in the seed without having to rely on sunlight, which is usually too dim, to meet their energy requirements. Because large seeds cannot be dispersed by the wind, these plants depend on a variety of animals to perform this function and have evolved many adaptations to encourage them to do so. Fruit bats are attracted by fragrant, sweet fruits typically borne conspicuously and conveniently on the outer parts of the tree canopy; the mango (Mangifera indica), native to the rainforests of India, provides a good example. The bats not only feed on fruits as they hang from the trees but also may carry a fruit away to another perch, where they eat the flesh and drop the seed. Smaller fruits may be swallowed whole, the seeds passing through the gut intact and being voided at a distance. The ground beneath trees used by fruit bats as a roost is commonly thick with seedlings of fleshy, fruit-bearing trees.

A variety of birds eat fleshy fruits also, voiding or regurgitating the unharmed seeds. Birds of different sizes are typically attracted to similarly scaled fruits, which are carried on stems of appropriate thickness and strength. For example, large pigeons in New Guinea feed preferentially on larger fruits borne on thicker stems that can bear not only the weight of the fruit but also the weight of the large bird; smaller pigeons tend to feed on smaller fruits borne on thinner twigs. In such a manner, the diverse plant community is matched by a similarly diverse animal community in interdependence.

Terrestrial mammals also help to disperse seeds. In many cases this has favoured the positioning of flowers and fruits beneath the canopy on the trunks of trees accessible to animals unable to climb or fly, an adaptation called cauliflory. In some cases fruits are grown in the canopy but drop as they ripen, opening only after they fall to attract ground-dwelling animals that will carry them away from the parent tree. The durian fruit (Durio zibethinus) of Southeast Asian rainforests is an example; its fruits are eaten and its seeds dispersed by a range of mammals, including pigs, elephants, and even tigers.

Mango (Mangifera indica). Robert C. Hermes from the National Audubon Society Collection/Photo Researchers—EB Inc.

Many other animals, from ants to apes, are involved in seed dispersal. In the Amazon basin of Brazil, where large areas of tropical rainforest are seasonally flooded, many trees produce fruit attractive to fish, which swallow them whole and void the seeds. Squirrels are also important seed dispersers in parts of South America. In the tropical rainforests of northeastern Australia, cassowaries are responsible for generating mixed clumps of tree seedlings of several species that grow from their dung sites.

It is important for seeds to be spread away from parent plants, both to allow seedlings to escape competition with the parent and to expand the range of the species. Another capacity important to seed survival, particularly in the diverse tropical rainforest community, involves the evasion of seed predators. Many different beetles and other insects are specialized to feed on particular types of seed. Seeds concentrated beneath a parent plant are easy for seed predators to locate. Seeds that are carried away to areas occupied by different plant species—and different seed predators—are more likely to survive.

In addition to dispersing seeds, animals are vital to tropical rainforest reproduction through flower pollination. Many insects such as bees, moths, flies, and beetles as well as birds and bats carry out this activity. Birds such as the hummingbirds of South and Central America and the flower-peckers of Asia have adaptations that allow them to sip nectar from flowers. In the process they inadvertently become dusted with pollen, which they subsequently transport to other flowers, pollinating them. The plants involved also show special adaptations in flower structure and colour. Most flowers pollinated by birds are red, a colour highly visible to these animals, whereas flowers pollinated by night-flying moths are white or pink, and those pollinated by insects that fly during the day are often yellow or orange. Bats are important pollinators of certain pale, fragrant flowers that open in the evening in Asian rainforests.

When two or more species in an ecosystem interact to each other’s benefit, the relationship is said to be mutualistic. The production of Brazil nuts and the regeneration of the trees that produce them provide an example of mutualism, and in this case the interaction also illustrates the importance of plant and animal ecology in maintaining a rainforest ecosystem.

Euglossine bees (most often the females) are the only creatures regularly able to gain entrance to the Brazil nut tree’s flowers, which have lids on them. The bees enter to feed on nectar, and in the process they pollinate the flower. Pollination is necessary to initiate the production of nuts by the tree. Thus, the Brazil nut tree depends on female euglossine bees for pollination.

Male euglossines have a different role in this ecological process. To reproduce, the males must first prove themselves to the females. The males accomplish this by visiting orchids for the single purpose of gathering fragrant chemicals from the flowers. These fragrances are a necessary precondition of euglossine mating. Without the orchids of the surrounding rainforest, the euglossine population cannot sustain itself, and the Brazil nut trees do not get pollinated. For this reason, Brazil nuts used for human consumption must be collected from the rainforest; they cannot be produced on plantations.

Once the Brazil nut pods are formed, the tree then depends on the agouti, a rodent, to distribute and actually plant the seeds. The agouti is one of the few animals capable of chewing through the very hard pod to reach the nuts inside. Agoutis scatter and bury the nuts for future consumption, but some nuts manage to sprout and grow into mature trees.

Of all vegetation types, tropical rainforests grow in climatic conditions that are least limiting to plant growth. It is to be expected that the growth and productivity (total amount of organic matter produced per unit area per unit time) of tropical rainforests would be higher than that of other vegetation, provided that other factors such as soil fertility or consumption by herbivorous animals are not extremely low or high.

Various methods are employed to assess productivity. Gross primary productivity is the amount of carbon fixed during photosynthesis by all producers in the ecosystem. However, a large part of the harnessed energy is used up by the metabolic processes of the producers (respiration). The amount of fixed carbon not used by plants is called net primary productivity, and it is this remainder that is available to various consumers in the ecosystem—such as the herbivores, decomposers, and carnivores. Of course, in any stable ecosystem there is neither an accumulation nor a diminution in the total amount of organic matter present, so that overall there is a balance between the gross primary productivity and the total consumption. The amount of organic matter in the system at any point in time, the total mass of all the organisms present, is called the biomass.

The biomass of tropical rainforests is larger than that of other vegetation. It is not an easy quantity to measure, involving the destructive sampling of all the plants in an area (including their underground parts), with estimates made of the mass of other organisms belonging to the ecosystem such as animals. Measurements show that tropical rainforests typically have biomass values on the order of 400 to 700 metric tons per hectare, greater than most temperate forests and substantially more than other vegetation with fewer or no trees. A measurement of biomass in a tropical deciduous forest in Thailand yielded a value of about 340 metric tons per hectare.

Increase in biomass over the period of a year at one rainforest site in Malaysia was estimated at 7 metric tons per hectare, while total litter fall was 14 metric tons, estimated mass of sloughed roots was 4 metric tons, and total live plant matter eaten by herbivorous animals (both invertebrate and vertebrate) was about 5 metric tons per hectare per year. These values add up to a total net production of 30 metric tons per hectare per year. Respiration by the vegetation itself was estimated at 50 metric tons, so that gross primary productivity was about 80 metric tons per hectare per year. Compared with temperate forests, these values are approximately 2.5 times higher for net productivity and 4 times higher for gross productivity, the difference being that the respiration rate at the tropical site was 5 times that of temperate forests.

Despite the overall high rates of productivity and biomass in tropical rainforests, the growth rates of their timber trees are not unusually fast; in fact, some temperate trees and many smaller herbaceous plants grow more rapidly. The high productivity of tropical rainforests instead results in their high biomass and year-round growth. They also have particularly high levels of consumption by herbivores, litter production, and especially plant respiration.

As recently as the 19th century tropical forests covered approximately 20 percent of the dry land area on Earth. By the end of the 20th century this figure had dropped to less than 7 percent. The factors contributing to deforestation are numerous, complex, and often international in scope. Mechanization in the form of chain saws, bulldozers, transportation, and wood processing has enabled far larger areas to be deforested than was previously possible. Burning is also a significant and dramatic method of deforestation. At the same time, more damage is being done to the land that is the foundation of tropical forest ecosystems: heavy equipment compacts the soil, making regrowth difficult; dams flood untouched tracts of wilderness to produce power; and mills use wood pulp and chips of many tree species, rather than a select few, to produce paper and other wood products consumed primarily by the world’s industrialized nations. Although political, scientific, and management efforts are under way to determine means of slowing the destruction of tropical forests, the world’s remaining acreage continues to shrink rapidly as demand for wood and land continues to rise.

The implications of forest loss extend far beyond the borders of the states in which the forests grow. The role that rainforests play at the global level in weather, climatic change, oxygen production, and carbon cycling, while significant, is only just beginning to be appreciated. For instance, tropical rainforests play an important role in the exchange of gases between the biosphere and atmosphere. Significant amounts of nitrous oxide, carbon monoxide, and methane are released into the atmosphere from these forests. This metabolism is being changed by human activity. More than half the carbon monoxide derived from tropical forests comes from their clearing and burning, which are reducing the size of such forests around the world.

Another consequence of deforestation must be examined. In the upper Amazon River basin of South America, the rainforest recycles rains brought primarily by easterly trade winds. Indeed, surface transpiration and evaporation supply about half the rainfall for the entire region, and in basins of dense forest far from the ocean such local processes can account for most of the local rainfall. Should the Amazon Rainforest, which accounts for 30 percent of the land area in the equatorial belt, disappear, drought would likely follow, and the global energy balance might well be affected.

The primary forces causing tropical deforestation and forest degradation can be tied to economic growth and globalization and to population growth. Population growth drives deforestation in several ways, but subsistence agriculture is the most direct in that the people clearing the land are the same people who make use of it. Rural populations must produce what food they can from the land around them, and in the rainforest this is most often accomplished via slash-and-burn agriculture. Forest is cleared, the cuttings are burned, and crops are planted for local consumption. However, the infertile tropical soils are productive for only a few years, and so it is soon necessary to repeat the process elsewhere. This form of shifting agriculture has been practiced sustainably among aboriginal cultures worldwide for centuries. Small patches of forest are cleared and abandoned when they become unproductive. The community then settles another isolated part of the forest, thus allowing previously settled land to regenerate.

However, in areas throughout the tropics larger populations than before now live at the forest margins. As subsistence agriculture progresses onto adjacent land, there is no opportunity for regeneration, especially if the shifting population is increasing. In some regions lowland forests have already been exhausted, and upland forests have been cleared. Land located on the slopes of hills and mountains is particularly susceptible to erosion and, therefore, to loss of the topsoil needed to sustain vegetation—arboreal or agricultural. Lowland tropical forests are not immune to erosion, however, as the heavy rainfall washes away unprotected soils.

Another subsistence-related factor in deforestation is demand for fuelwood, which is the main source of energy for 40 percent of the world’s population. As population increases, this demand exerts significant and growing pressure on tropical forests, particularly in Africa.

Urban population growth has led to the establishment of resettlement programs in several countries. Governments have made land available to poor families in overcrowded cities, who then have attempted to begin new lives from cleared forest. In Brazil the Transamazonian highway system was begun in the 1960s to enable development and settlement of the Amazon Rainforest. Part of the Transamazonian highway, called BR 364, penetrates the remote state of Rondônia in west-central Brazil. Since the highway’s construction, this region has undergone significant deforestation. Main roads are cut into the forest, and parallel sets of access roads allow access to individual plots of land that are settled by farmers. This method of settlement results in a characteristic “fishbone” pattern when the land is viewed from above.

Small farms line the slopes in the highlands of Burundi, one of the most densely populated regions in Central Africa. Dr. Nigel Smith/The Hutchison Library

Brazil’s resettlement program, while extensive, is by no means the largest. Population resettlement to provide agricultural employment and access to land is also important in some Southeast Asian countries, notably Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam. By far the largest program has been conducted in Indonesia, where more than four million people have been voluntarily resettled from Java and Bali to the less-populated islands, especially to the province of Irian Jaya on the island of New Guinea. Despite considerable success, the program has been plagued by such problems as improper site selection, environmental deterioration, migrant adjustment, land conflicts, and inadequate financing. A program in Malaysia has been quite successful, in part because it set much smaller settlement targets and was better funded. Vietnamese development policy also utilized the resettlement of people in an effort to revitalize areas outside the major population centres.

While resettlement in Malaysia or Indonesia entails sea travel to isolated islands, roads connect South American population centres to the Amazon, where frontier cities draw both unsuccessful farmers from rural areas and migrants from established cities. The Amazon basin has long been relatively uninhabited, but improved diets and sanitation and the greater ease of transportation are making it more attractive for human settlement. From the mid-1940s onward, a number of “penetration roads” have been built from the populous highlands of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia into Amazonia, often in conjunction with Brazil’s Transamazonian highway. These roads have funneled untold numbers of landless peasants into the lowlands. Its vast area notwithstanding, the Amazon basin by the late 20th century had a predominantly urban population. Almost one-third of the estimated nine million Brazilians living in the 4.9 million-square-km (1.9 million-square-mile) area officially designated as Legal Amazonia were concentrated in Belém and Manaus, each with more than one million inhabitants, and in Santarém. These cities, which are logistic bases of operations for cattle ranching, mining, timber, and agroforestry projects, are still growing rapidly, with modern residential towers and shantytowns standing side by side. Even frontier trading centres in the interior, such as Marabá, Pôrto Velho, and Rio Branco, have 100,000 or more inhabitants. In the upper reaches of the drainage area, places such as Florencia in Colombia, Iquitos and Pucallpa in Peru, and Santa Cruz in Bolivia have become significant urban centres.

This map shows Brazil and its extensive river systems. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Most of those who come to the Amazon in resettlement programs are ill-prepared to become frontier farmers in an environment so naturally unsuitable to field agriculture, and the plots are soon abandoned. But the forest does not often reclaim the land; it is usually taken over by cattle ranchers first. In the Amazon and Central America the single largest use of cleared land is beef production—most of it for export. Cattle ranching thus illustrates how economic growth and globalization drive deforestation; other examples include logging and mining.

Tropical forests throughout the world often grow atop rich mineral deposits that are most easily mined by first clearing away the forest. The minerals are then extracted and sold in the global marketplace by the governmental or corporate enterprises involved. Even small tropical islands such as Fiji and New Caledonia have not been immune to deforestation by mining. In addition to clearing forests to gain access to deposits, mining also adds to deforestation by taking wood from the surrounding forest for ore processing. Such is the case in the Carajás region of Brazil, where tropical forest trees fuel iron smelters.

Gold deposits have been found in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, as well as in the tropical forests north and south of the Amazon River. The resulting Amazon “gold rush” has brought as many as a half million transient miners (garimpeireos) equipped with picks, shovels, and sluice boxes to search for the mineral in alluvial deposits. Brazil’s annual production peaked in 1987 at nearly 90 tons, declining thereafter. Meanwhile, the mercury used in extracting the gold polluted waterways, causing the fish that are so important in the local diet to become inedible. On the Madeira River teams operating from rafts pump auriferous sediments from the riverbed; the sediments are subjected to a similar treatment.

Ostensibly, countries possessing tropical forests seek sources of trade, such as mining and logging, and income to raise their populations’ standard of living. It is often argued, however, that the underlying cause of economic dilemmas facing these governments is that control of resources is too concentrated among a wealthy few. Furthermore, these decision makers are not always from the developing countries, as multinational corporations can wield substantial influence on developing or unstable economies.

A common denominator in the destruction of tropical forests worldwide has been the pursuit of short-term gains at the expense of long-term prospects, both economic and environmental. By the end of the 20th century the importance of tropical forests had been realized, and conservation had become a subject of international politics. The institutional arrangements controlling tropical forests began to change significantly as the roles of environmental and other nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) at local, national, and international levels expanded. Recent changes have resulted in some measure of progress: development projects have been halted; sustainable management programs have become a focus of research; developing countries have established governmental departments to oversee the use of natural resources; and a broader range of interest groups, such as indigenous tribal peoples, are being considered. Protected areas are being set aside throughout the world as cooperation between institutions at the international level is realized. In 1997, for example, Brazil established 57,000 square km (22,000 square miles) of land as protected rainforest in the state of Amazonas, creating the world’s largest rainforest reserve.

Large iron mine in the Serra dos Carajás, Pará state, Brazil. © Tony Morrison/South American Pictures

The recent emergence of the ecotourism industry is a phenomenon that relies on the cooperation of various groups with interests in tropical forests. Ecotourism is recreational travel for the purposes of observing and experiencing natural environments. Rainforests are popular destinations, and these sites are often jointly operated by a combination of governmental, private, environmental, and indigenous groups. Ecotourism facilities also serve as biological research stations, and vice versa. In this way ecotourism can be seen as contributing to conservation efforts.

Such changes, while encouraging, are only beginning to work against the continuing decrease in acreage. International agreements among governments and businesses are highly dependent on the cooperation and commitment of the parties involved. Enforcement of policies at all levels of government, both within and between countries, is problematic. The record extent of fires in Amazonia and Indonesia in 1997–98 underscored profound problems in spite of recent progress. The relationships between oftentimes competing groups—local, national, and international; economic and environmental; governmental and nongovernmental—are what will determine the future of the planet’s tropical forests.

A temperate forest is a vegetation type with a more or less continuous canopy of broad-leaved trees. Such forests occur between approximately 25° and 50° latitude in both hemispheres. Toward the polar regions they grade into boreal forests, which are dominated by evergreen conifers, so that mixed forests containing both deciduous and coniferous trees occupy intermediate areas. Temperate forests usually are classified into two main groups: deciduous and evergreen.

Deciduous forests are found in regions of the Northern Hemisphere that have moist, warm summers and frosty winters—primarily eastern North America, eastern Asia, and western Europe. In contrast, evergreen forests—excepting boreal forests, which are covered in boreal forest—typically grow in areas with mild, nearly frost-free winters. They fall into two subcategories: broad-leaved forests and sclerophyllous forests. (Sclerophyllous vegetation has small, hard, thick leaves.) The former grow in regions that have reliably high, year-round rainfall; the latter occur in areas with lower, more erratic rainfall. Broad-leaved forests dominate the natural vegetation of New Zealand; they are significantly represented in South America, eastern Australia, southern China, Korea, and Japan; and they occur in less well-developed form in small areas of southeastern North America and southern Africa. Sclerophyllous forests occur particularly in Australia and in the Mediterranean region.

Temperate forests originated during the period of cooling of world climate that began at the start of the Cenozoic Era (65.5 million years ago). As global climates cooled, climatic gradients steepened with increasing latitude, and areas with a hot, wet climate became restricted to equatorial regions. At temperate latitudes, climates became progressively cooler, drier, and more seasonal. Many plant lineages that were unable to adapt to new conditions became extinct, but others evolved in response to the climatic changes, eventually dominating the new temperate forests. In areas that differed least from the previously tropical environments—where temperate evergreen forests now grow—the greatest numbers of plant and animal species survived in forms most similar to those of their tropical ancestors. Where conditions remained relatively moist but temperatures dropped in winter, deciduous trees evolved from evergreen rainforest ancestors. In areas that became much more dry—though not to the extent that tree development was inhibited and only scrubland or desert environments were favoured—sclerophyllous trees evolved.

During the rapid climatic fluctuations of the past two million years in which conditions alternated between dry, cold glacial states—the ice ages of some northern temperate regions—and warmer, moister interglacial intervals, tree species of temperate forests had to migrate repeatedly to remain within climates suitable for their survival. Such migration was carried out by seed dispersal, and trees that were able to disperse their seeds the farthest had an advantage. In the North American and European regions where ice-sheet development during glacial intervals was most extensive, the distances that had to be traversed were greatest, and many species simply died out. Extinctions occurred not only where migration distances were great but also where mountains or seas provided barriers to dispersal, as in southern Europe. Thus, many trees that were formerly part of the European temperate forests have become extinct in the floristically impoverished forest regions of western Europe and are restricted to small refuge areas such as the Balkans and the Caucasus. For example, buckeye (Aesculus) and sweet gum (Liquidambar) are two trees that no longer occur naturally in most parts of Europe, having disappeared during the climatic turmoil of the past two million years.

Human activities have had pronounced effects on the nature and extent of modern temperate forests. As long ago as 8,000 years, most sclerophyllous forests of the Mediterranean region had been cut over for timber or cleared to make space for agricultural pursuits. By 4,000 years ago in China the same process led to the removal of most broad-leaved and deciduous forests. In Europe of 500 years ago the original deciduous forests had disappeared, although they are remembered in nursery tales and other folklore as the deep, wild woods in which children and princesses became lost and in which dwarfs and wild animals lived.

The deciduous forests of North America had been cleared almost completely by the end of the 19th century. Australia and New Zealand experienced similar deforestation about the same time, although the earlier activities of pre-European peoples had substantial impacts. The character of the Australian sclerophyllous forests changed in response to more than 38,000 years of burning by the Aboriginal people, and the range of these forests was expanded at the expense of broad-leaved forests. In New Zealand about half the forested area, which previously had covered almost the entire country, was destroyed by fire brought to the island by the Polynesian inhabitants who arrived 1,000 years before the Europeans.

Winter in the temperate latitudes can present extremely stressful conditions that greatly affect the vegetation. The days are shorter and temperatures are low, so much so that in many places leaves are unable to function for long periods and are susceptible to damage from freezing. These conditions reduce the photosynthetic activity of the trees. In regions where winter temperatures regularly fall well below the freezing point and where soil moisture and nutrients are not in short supply, many trees have evolved a type of leaf that is relatively delicate and thin with a life span of a single growing season. Because such deciduous leaves do not require a large input of chemical energy, it is not too wasteful for the plant to shed them after a single growing season.

The “throwaway” leaves of temperate deciduous trees are shed as the days shorten in autumn and are replaced by new leaves in the spring. The forests dominated by these trees, therefore, have extremely pronounced seasonal changes in appearance, function, and climate. Most trees in temperate deciduous forests follow this habit, although some evergreen species usually are scattered among them. In particular, several broad-leaved evergreen shrubs are found in the understory of temperate deciduous forests that have less delicate, longer-lasting leaves than their deciduous neighbours; these leaves have adaptations that allow them to survive the freezing winter temperatures, and they can carry out photosynthesis for more than a single summer.

In areas where milder conditions prevail, however, photosynthesis may be possible at any season without need for protective mechanisms against frost damage. In these relatively unstressful circumstances most trees may benefit from retaining their leaves throughout the year, and heavy use of resources through frequent leaf replacement is thereby avoided. In environments such as these that also have a sufficient supply of moisture, temperate broad-leaved forests are found.

In mild but drier temperate environments, moisture shortage necessitates that trees develop thickened leaves. These leaves often have a reduced surface area or they dangle pendulously from limbs, two strategies employed to slow the loss of water (transpiration). High levels of energy and nutrients are needed to produce these thick leaves, which, therefore, cannot be replaced easily at annual intervals, an added reason for sclerophyllous trees to retain their leaves throughout the year. With foliage perennially present, these trees can carry out photosynthesis whenever moisture becomes available, provided temperatures are warm enough; this characteristic is advantageous where rainfall is infrequent and unpredictable.

Soils in temperate sclerophyllous forests are frequently poor in mineral nutrients. This poverty of nutrients accounts in part for the nature of the vegetation, because the annual production of leaves or the development of a dense broad-leaved canopy requires a significant input of nutrients. In contrast, soils in regions of deciduous and broad-leaved evergreen forest are generally fertile. (The forests that occupied the best soils in most regions, however, have been cleared almost completely to make way for agriculture.) Typical temperate deciduous forest soils are mull soils, which have a high level of organic matter especially close to the surface that is well mixed with mineral matter. Variations in soil materials and fertility have a strong influence on the types of trees that will dominate the forest. For example, in northwestern Europe, the European beech (Fagus sylvatica) dominates deciduous forests on shallow soils that overlie chalk, while oak (Quercus) is dominant on deeper, clay soils. The richness of the ground flora beneath the trees generally increases with soil fertility.

Intimate associations, or mycorrhizae, between tree roots and fungi are important and occur in most tree species. Although important in all forest types, these interactions have been studied more thoroughly in temperate deciduous forests. The fungal component of this symbiotic partnership grows on or in the fine roots of trees and benefits by obtaining nutrition in the form of carbohydrates from the tree root; the tree, in turn, is better nourished because a mycorrhizal root is more efficient at absorbing dissolved mineral nutrients from the soil than is an uninfected root.

Waterlogging of soils in temperate deciduous woodlands commonly occurs in regions with higher rainfall and humidity in late winter and spring, such as the British Isles. This occurs not only because in winter rainfall is higher and evaporation lower but also because the trees, barren of foliage, transpire a minimal amount of moisture. Areas subject to waterlogging include clay-rich soils, places that have low slope angles, depressions, and spots along watercourses. These places tend to have a richer ground flora but a less luxuriant tree canopy, which consists of only a few species that are tolerant of wet soils.