The editors of the book introduce Nicole Hoenig de Locarnini who is a senior advisory member within one of the “Big Four” companies moving toward strategy consulting. To date, she has devoted her professional life to developing deep technical insurance/reinsurance expertise at a major global insurance company followed by a successful career in management consulting. Her work spans companies and business units within the financial services, life sciences, and producing industries.

Introduction and Link to Our Three-Pillar Model

Connectivity in large professional services firms: Unlocking the potential power of partnership—when individual leaders become an assembly of superpowers

As already mentioned in the general introduction to the book, the business world is changing both drastically and quickly. It is obvious that professional services organizations and here management consulting firms are both subjects and objects of this disruptive development. On the one hand, more than other industries, they must ensure that they are among the first to understand the direction, key content, and the opportunities and risks of the forthcoming changes so that they are able to support their clients as well as possible.

In terms of our three-pillar model, the sustainable purpose of management consulting firms is obvious: to serve their clients as well as possible in delivering expertise, knowledge, temporary project resources, and success in the clients’ key initiatives and helping them to meet their overarching enterprise targets.

This also includes special support—expertise, knowledge, and resources but also coaching and mentoring—for the clients’ journey, which means, in terms of our three-pillar model, professional support of the clients’ traveling organization. On the other hand, we will see that the management consulting firm itself is on a journey as a result of external factors (e.g., the changing business world) and internal factors (e.g., changing workforce demands/the high staff turnover)—so the term “traveling organization” has two meanings for a management consulting firm: it is something to cope with as an organization in its own right, and it is also something to help other organizations to cope with. This means, among other things, that management consulting firms and clients have some overlaps in their development journeys.

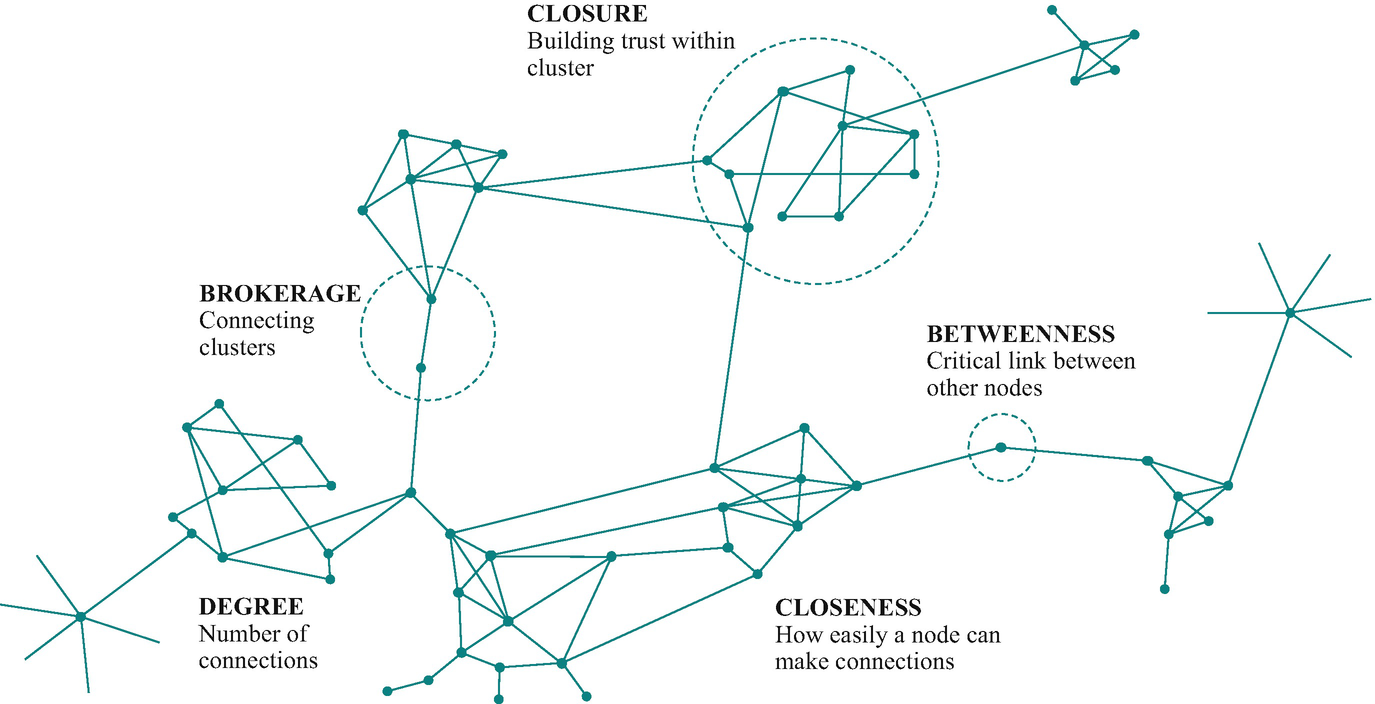

Under these circumstances, connectivity capabilities—connecting resources—are key because cooperation and managing interfaces are dominant in a knowledge-driven business as we will see below.

Executive Summary

In a more complex, connected world, the context of management consulting is changing. Globalization, digitalization, changing client demands and the impact of new ways of working requires a redefinition of the business model for management consulting, especially within the context of a “Big Four” company.

The differentiator for a successful organization in the future is a redefinition of the partnership in terms of its structure and of the role of the individual partners as connectors and shapers as well as the increased importance of individual development in this context.

Research conducted in 2016/2017 as part of an executive education program at Oxford Saïd Business School in collaboration with HEC Paris provides a modular framework for transformation across the three dimensions of the individual, the organizational, and the market context. The aim is to develop a lasting partnership as “aligned autonomy” in a network structure that is characterized by collaboration, with an emphasis on individual development, a redefinition of performance management and organizational learning. For reasons of confidentiality, the original dissertation is not accessible to the public but is available in a redacted version. Any references to interviewees within or outside of my firm have been removed. This chapter is based on some parts of this research with a short introduction to professional services firms, the changing situation of a global professional services firm, sustainable purpose, providing examples of organizational changes (the journey) as well as showcasing the need for connectivity in this complex environment.

Introduction to Professional Services Organizations

About 7 years ago, I began to explore opportunities for my next career move after 5 years in a large multinational insurance company. My mentor advised me to learn something that I had not learned before, so I decided to acquire some experience in a professional services firm (PSF): I opted for management consulting in the financial services sector at a “Big Four” company.

The “Big Four” are the four largest accounting firms and they handle accounting, tax, and advisory services for many public and private companies. The “Big Four” consist of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited (Deloitte), KPMG, and Ernst & Young (EY). The “Big Four” were formed in 2002 after a series of mergers reduced the original eight PSFs down to four. In 2015, the “Big Four” had a global revenue of USD125 billion across all service lines (audit, tax, advisory, legal) with about 838,000 employees. By comparison, the largest global company by revenue is Walmart with revenues of USD482 billion and 2.3 million employees in 2015. By way of comparison, Allianz Insurance had global revenues of USD123 billion in 2015 with “only” 142,000 employees.

When talking to some of my peers working in other “Big Four” firms or management consulting firms, I realized that many characteristics of the organizations and their partners are the same. It is not possible to make a generalization regarding what we do. The work experience depends to a great extent on the individual partners, who are responsible for the internal teams and the projects they can sell to clients.

From an academic and organizational point of view, Morris and Empson (1998) define a PSF as “an organization that trades mainly on the knowledge of its human capital, i.e., its employees and the producer-owners, to develop and deliver intangible solutions to client problems.” In “Managing the professional service firm,” Maister (1993) describes the two characteristics that make PSFs different from any other company. First, most of the work demands a high level of customization, and second, professionals engage in a great deal of personal client interaction. The Oxford Handbook of Professional Service Firms was published in 2015 by Empson et al. as a collection of articles about PSFs, including their context, their management, their organization, and their intercompany interactions. In publishing this handbook of up-to-date research, the editors want to legitimize PSFs as a relevant area for academic study. “Despite their empirical significance and theoretical distinctiveness, for many years, PSFs remained very much in the shadows of organizational research” (Empson et al. 2015). It is difficult, if not impossible, to gain holistic information about the size of the industry, as most organizations are privately owned and not legally required to disclose financial information. For example, financial information on non-“Big Four” consulting provided by strategy firms (McKinsey, BCG) or IT consulting (Accenture, IBM) was not included due to lack of information. Moreover, it is a challenge to decide which companies to include for the management consulting market, due to issues of confidentiality, size, and geographical coverage. Furthermore, the market itself cannot be clearly defined.

Defining characteristics of a PSF as differentiator to other professions (Figure: from Author’s thesis at HEC Paris—Oxford Saïd Business School “Unlocking the potential power of partnership—when individual leaders become an assembly of superpowers”) [adapted by author from Empson et al. (2015)]

First, a PSF’s primary activity is the application of knowledge for the development of customized solutions to clients’ problems. Second, this knowledge comprises both specialist technical knowledge and in-depth knowledge about their clients. Third, a PSF’s governance is characterized by extensive individual autonomy and contingent managerial authority. Fourth, a PSF’s identity is shaped by its clients and other peers. Professionals within PSFs establish their reputation as experts in certain fields and are therefore recognized for these skills by their clients, who are willing to pay for these skills, and secondly by their peers both within and outside their organization.

The editors state that while “many organizations will possess some of these characteristics […] a PSF will possess all of them to varying degrees” (Empson et al. 2015, p. 9).

Integrative framework for analyzing PSFs (Figure: from Author’s thesis at HEC Paris—Oxford Saïd Business School “Unlocking the potential power of partnership—when individual leaders become an assembly of superpowers”) [adapted by author from Empson et al. (2015)]

PSFs are interconnected with their professionals who are directly responsible for the success of the PSF. Client demands need to be mapped with the PSFs’ abilities to conduct business. Competitors are directly competing for the most relevant resources. Following the idea of the traveling organization, PSFs will, with this “in mind,” be able to navigate this complexity whatever the market or competitors come up with.

Maister states that “professional services firms compete in two marketplaces; they compete for clients and they compete for staff” (1993, p. 189), which are both equally important and intertwined. Professional regulators, especially in the context of a “Big Four” organization, provide potential challenges to the PSF due to its multidisciplinary structure. “Big Four” organizations are based on the traditional audit business and are therefore potentially always in a conflict of independence with their management consulting service line(s). The auditor’s duty is to uphold the public interest, whereas the consultant’s duty is client satisfaction. The different elements of a PSF shape its organizational practice, but their demands can conflict. Many professional services firms are managed as partnerships. With the creation of the public corporation in the nineteenth century, the partnership developed as the predominant form of organizational governance (Greenwood and Empson 2003). Gage (2004) states that “the most exciting advantage of partnership is the potential it creates for synergy” (p. 7) and that partners should handle their work according to their individual strengths and preferences (p. 9). In his view, the key factor for a successful partnership is simple: “ask people in a successful partnership what makes it work so well and they are very likely to respond with ‘trust’” (p. 45). The concept of trust and psychological security was examined in great detail as part of this research but, owing to the narrower focus of this chapter, is not detailed here.

According to Maister (1993), every PSF has only three goals: “outstanding service to clients, satisfying careers for its people and financial success for its owners” (p. 223). When referring to owners in a PSF, in the “Big Four” and most management consulting firms, these are the partners. In Maister’s view, PSFs mirror medieval guild structures, which used a hierarchy of apprentices, journeymen, and masters. The company’s profitability drops significantly when senior people fail to delegate routine jobs to more junior people. He claims that “people do not join professional services firms for jobs but for careers” (p. 129). The turnover rates in organizations like my organization is about 15–20% on an annual basis. Some firms intentionally use a high turnover strategy to find and retain the best people. In this way, partners can make more money from junior people without the immediate prospect of promoting them. If a PSF has a good reputation, more people will want to join it and although they know that their chances of promotion might be small, they believe they can benefit from just being at the firm and having it on their resumé.

Today’s Challenges for Professional Services Firms: Redefining Business Models and Transforming Themselves

Today’s world is increasingly complex, due to a higher level of connectivity, a constant (over)flow of information, and the speed of transmission of all kinds of information. It is a VUCA world: a world of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, which has a significant impact both on individuals and on society in general. PSFs in the management consulting sector have experienced growth over the last few years, despite significant changes in terms of technology and legislation. This has put the industry in a good position, but there are still challenges, and like every professional services industry, management consulting is defined by the needs of its client’s—as they change, so too must the industry. For the upcoming journey, the focus of PSF must be on enhancing their operational processes and “doing more with less.” For many, the key to success lies in implementing a comprehensive transformation and digitalization within a newly embedded ecosystem.

The first being the ongoing war for talent. Competition is fierce, and many firms have been forced to do one of two things—either explore service and product offerings that do not rely on their ability to sell people or look outside the traditional talent recruitment pool of universities and focus more on skills than qualifications.

The second factor is the need for collaboration. As specialist and disruptor firms appear it becomes more apparent that, to succeed, PSF firms will need to partner with each other in order to meet the full breadth of client demands—within their own organization (as dispersed local firms and regions) and outside their own organization. This does not solely mean a large firm partnering with, or acquiring, various start-ups—more and more it is about a firm partnering with technology or academic partners to widen the scope of potential client experience.

The third factor is the consideration on how to move away from traditional “body-selling”’ business models to an output-focused model that shares risks and rewards with clients. Today’s client requirements have changed in the sense that traditional consulting no longer works with “out-of-the-box solutions” that just have to be “plugged in” to the clients’ organization. Increasingly, there is a demand for co-creation and co-design as neither the client nor the consulting firm has done exactly this project before; yet there is the trust that, somewhere in an organization of 250,000 consultants, someone might have conducted a similar project where the knowledge can be applied to this new client situation. This is the core strength of an international PSF when done well—connectivity.

For our clients, one of the biggest challenges is industry convergence. There is a need to be connected so as to cross-leverage and understand “connectors.” Industry convergence is largely the outcome of evolutions in technology and consumer behavior. The disruption caused by digitalization and hyper-connectivity creates a business landscape where previously distinct or separate industries begin to converge—changing their traditional services and methods of operation because of competition from new, digitally enabled business models. We are seeing a new wave of industries being redefined as supplier and customer relationships continue to be challenged. Healthcare, energy, and financial services are prime examples of industries that were traditionally ruled by a few corporations but have seen new entrants from other sectors and start-ups. Industry disruption and convergence are happening at an unprecedented pace. Convergence is not only blurring the lines between industries, it is also creating new markets and new opportunities for companies or governments to grow and compete in a world where everything is connected. One of the most significant symptoms of convergence is ecosystems. Companies used to compete within one core industry; however, as issues become more complex and technology allows new entrants, ecosystem collaboration is becoming the new normal. Several large companies are investing in other entities to give them the opportunity to experiment with more agile processes, risky new propositions and cutting-edge technology. This is particularly prevalent in the healthcare industry where a lot of R&D is now being undertaken through alliances. The role of the management consultants, who have a holistic market overview, is to act as facilitators and connectors to create the “right” connections—thinking with, for, and one step ahead of our clients—through the different market perspectives and insights we get from our numerous projects. Various examples can be observed in merging, e.g., insurance and life sciences companies or bringing quantitative models used in the financial services industry to the producing industry with great success thanks to the increased use of data and predictive analytics.

Management Consulting as a Context for Constant Change: Being Continuously on a Journey

In his article, “Consulting on the cusp of disruption” in the Harvard Business Review (2013), Christensen highlights that a disruption of the management consulting industry is inevitable. Yet, many consultants interviewed stated the difficulty of “getting large partnerships to agree on revolutionary strategies” (p. 10). He stated that the primary assets of management consulting “are human capital and their fixed investments are minimal” (p. 5). The only asset or “product” the companies possess is their employees. These employees are directly linked to the company’s performance measurement. The management consulting industry has a constantly high influx of new, highly motivated young talent. People are usually hired at the lower ranks of the organization. Internal growth opportunities are then provided by the organization and the “organizational pyramid” is maintained. A constant number of people also drop out of these organizations due to, for example, a change in lifestyle or because they receive other offers (Maister 1993). Consulting still has an “up or out” mentality, although this is currently changing with the ambition to attract diverse talent (from normal business management to strong IT skills) and to provide different career paths with more flexibility. Newer talent has different expectations and organizations increasingly struggle to attract exceptional talent as the organizational set-up is still very hierarchical and linear in terms of promotion. In his article “When McKinsey met Uber: the gig economy comes to consulting” (2016), Hill describes the rise of young freelancers that have been trained in large consulting companies and are changing the consulting market. According to his survey of 100 independent consultants, 59% stated a career change, higher flexibility and working with clients in a different way as main drivers for independence. In terms of future workforce planning, different engagement models need to be considered.

The average annual staff turnover rate in the management consulting industry is about 15–20% (Batchelor 2011). Every fifth or sixth person hired will leave the organization within a year. Management consulting organizations are trying to overcome this fact by establishing a unique “culture” for the members of the organization. My own organization recently rebranded its mission statement to “EY—Building a better working world.” This statement is meant to express a common understanding that is built on shared assumptions and beliefs, and on the norms and interpretations of what EY is. Furthermore, it means that a person knows what they can expect when they work with another person from EY anywhere in the world. With increasingly complex activities and working across regional boundaries, the individual’s contribution to the team success is hard to measure. “The more people collaborate, the harder it becomes to determine who contributed what to the ultimate solution” (Morieux and Tollman 2014, p. 14). Furthermore, new business models in consulting arise with the emergence of alternative PSFs working with (senior) freelancers on talent platforms that are often required to work with an existing project team (Christensen et al. 2013).

The Self in Management Consulting: Emotional Intelligence as Enabler for Connectivity

Runde (2016) claims in a Harvard Business Review article that the critical distinguishing factor for advancing in professional services is emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence is the ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions and to use this information to guide thinking and related behavior. Goleman wrote in 1998 that “without it, a person can have the best training in the world, an incisive, analytical mind and an endless supply of smart ideas but he still won’t make a great leader.” In today’s more complex and global business environment, stronger communication across multiple boundaries is required. Emotional intelligence is described by Runde as a combination of adaptability (relationship with self—self-awareness), collegiality (relations with colleagues—collaboration), and empathy (relationship with clients). Self-awareness is the ability to understand strengths and weaknesses and to recognize emotions and how they affect thoughts and behaviors. In the management consulting environment, self-awareness helps one to adapt to several different supervisors, colleagues, clients, and working styles, which is inherently built into the management consulting working model consisting as it does of varying projects and project teams. Collaboration is essential in management consulting, as most of the work is done in teams, regardless of the rank of the individual. Teams are becoming global and diverse and the workplace itself is becoming more virtual. Teams are also becoming larger as they attempt to solve complex client problems that span functions and sometimes even industries. It is important for team members to respect each other’s ability and perspectives. Goleman states that empathy is understanding what others are feeling. “Empathy allows you to build trust with your clients—and this is the most challenging and underappreciated part of any job in the professional services industry” (Runde, p. 3).

In management consulting, the challenge is to encourage the client to tell you their actual problem. From his perspective, similar to Maister, “the key to winning business is getting the client to trust or like you enough that they will tell you what issues are worrying them” (Maister 1993, p. 3). Runde (2016) considers the ability to listen the most important capability and he distinguishes two types—those who listen to respond (“encyclopedia”) and those who listen to listen (“empathizer”). The encyclopedia listens to provide the client with his knowledge, whereas the empathizer listens to understand the issues and then asks the right questions. These are skills that can be learned, and they are an important success factor for partners in management consulting. In the past, “the lone wolf” was a common pattern for highly successful partners, yet today “hunting in a wolf pack” is required as large scale, and complex problem-solving skills are not the remit of just one partner but rather of teams of subject matter experts covering all angles of client issues. In the research, the partnership in a PSF was compared to a football (soccer) team. In the past, the German football team, for example, would have had two or three stars, and the rest of the team would have comprised good yet run-of-the-mill players. In today’s national team, every single player in each position is a highly trained, excellent star in his own right. Yet, the common team purpose is aligned around winning the match.

Partners are co-owners of the organization, and following various statements by key managing partners from my own, but also other management consulting organizations, the partnership is still viewed as the best possible company model since it provides a key sense of ownership and responsibility among the individual partners. This influence is much higher than in a normal corporation and provides a high degree of flexibility and agility.

From my perspective, there is often not yet enough leadership and understanding of the new era of complexity. This is especially evidenced by the fact that partners are often not yet able to think in network and collaboration structures and have old belief systems rooted in “hard” facts, such as their own incentivization. Empson et al. (2015) highlight that PSFs present distinctive leadership challenges given the professionals’ traditional expectation of liberation from organizational constraints. It is argued that leadership in PSFs manifests itself “explicitly through professional expertise, discretely through political interaction, and implicitly through personal embodiment” (p. 19). However, they state that these traits are “rarely combined in single individuals, which gives rise to the prevalence of collective forms of leadership supported by embedded mechanism[s] of social control” (p. 19).

The connected company—[Figure: adapted by author from Gray and Vander Wal (2012)]—It shows a general architecture of a connected enterprise. This architecture must be concretized and tailored for each industry, and even each enterprise, to make it operational

I do not intend to go into too much detail here (as this would be an entire new chapter) yet the mainly dominant individual performance management system for partners in the management consulting industry was highlighted in the interviews as being one of the main inhibitors for collaboration as well as a lack of lack of long-term business focus as the incentive scheme is based on an annual result basis. Different metrics and objectives must be developed between different roles (sales roles, delivery roles, development roles) as one cannot exist without the other (and not all skills are usually found in one individual partner) and the interplay is crucial, creating reciprocity.

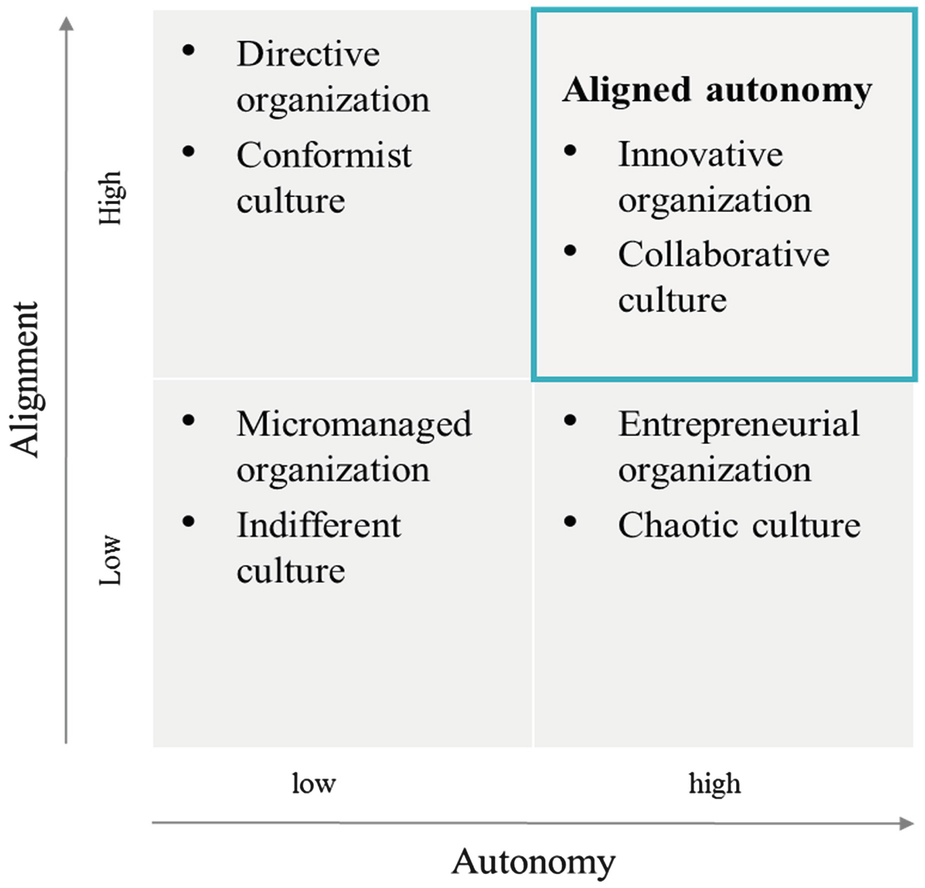

Organizational implications of autonomy and alignment [Figure: adapted by author from Kniberg (2016)]

An organization with low autonomy and low alignment is a micromanaged organization with an indifferent culture. High autonomy and low alignment lead to an entrepreneurial organization with a chaotic culture due to the lack of clear direction. Low autonomy and high alignment form an authoritative organization and lead to a conformist culture. High autonomy and high alignment—in short, aligned autonomy—lead to an innovative organization with a collaborative culture aiming for a common goal.

Full autonomy in any organization can lead to a duplication of tasks. Therefore, appropriate communication and knowledge-sharing mechanisms need to be in place to ensure organizational learning without sacrificing too much autonomy in the organization.

The disruption of management consulting is not hypothetical despite having already undergone periods of change on all sides by competitors and new technologies. Management consultants have maintained status and growth through prestige, branding, and long-time client relationships but, ultimately, they are no more immune to the forces of disruption than any other industry especially because of the forces relating to the future of work and various emerging facilitated networks of well-trained and specialized freelance consultants. Every day, there are more ex-consultants pursuing a more balanced lifestyle who are ready to share their expertise. Every day, the tools that companies can use to form their strategy improve and become more advanced. And every day, consulting firms need to prove that they can be relevant in this new world—and not simply because of their prestigious name. With a sustainable purpose, with the understanding that the organization is on a continuous journey in pursuit of the optimum outcome and finally with better ways of connecting available resources within and outside the organization, I believe that PSFs are nowadays well equipped to play a redefined role in today’s exponentially changing world.