21

A Tale in Three Parts

How Joron Woke

It was early, the scent of fish filled his nose and worked its way into his stomach, awakening the burgeoning nausea. His head ached and his hands trembled in a way that would only be stilled by the first cup of shipwine. Then the pain in his mind would fade as the thick liquid slithered down his gullet, warming his throat and guts. After the first cup would come the second and with that would come the numbness that told him he was on the way to deadening his mind the way his body was dead, or waiting to be. Then there would be a third cup and then a fourth and then a fifth and the day would be over and he would slip into darkness.

No.

That was not him. Once him, not him any longer.

That was Joron Twiner the lost, Joron Twiner before Meas, before Tide Child flew the sea, before he sang a legend to the aid of his ship with the gullaime. That was not Joron Twiner the deckkeeper, that was Joron Twiner the broken.

He was Joron Twiner the deckkeeper.

The deckkeeper, Joron Twiner, tried to open his eyes, experienced a moment of confusion when he realised that his eyes were already open. Oh, he thought. He closed his eyes. Opened them. It made no difference. All was darkness.

Panic.

What was this, some dream brought on by the medicine of the hagpriests? He tried to sit, choked, a rope around his neck. Ropes around his wrists, his midriff, his legs and his ankles. Walls, close on either side, a roof so near he could feel the warmth of his own breath bouncing off it as he gasped. He was in a box. Why was he in a box?

Struggling, pain. Pain in his throat. Bruising.

He tried to shout.

Nothing.

Only pain. A croak. That voice of his, that deep tenor his father had loved. The voice that sang up legend.

Gone. A creak, like a boneship catching the wind.

Light streaming in, blinding him, forcing his eyes shut. Some of that light still bleeding through. Forcing tears into his eyes. Blinding him.

“Joron.” He knew that voice. “I’m sorry about all this, Joron. Just following orders, you understand?”

He let his eyes open, ever so slowly. The light was not bright, not really, not full daylight. Only lamplight, flickering and dim. But it still hurt. The air smelled of outside, the melting gion, old fish. A shadow loomed above him. He tried to speak, only a croak came out.

“Don’t speak, my man was a little too rough with the garrotte, I am afraid. Don’t be rough with him, says I. Joron is a good fellow, says I, but they did not listen. I imagine your throat will be sore for quite some time, though to be fair, it is the least of your worries.”

“Gueste?” The name slipped out. His words both quiet and harsh, a rasp in his throat. “What?”

A finger on his lips. “Shhh, do not speak.”

In the light, now the tears had flowed from his eyes, he could make out Gueste’s face, sardonic, smiling still. The glimmer of Skearith’s Bones in the sky far above her. “In a story, Joron Twiner, I would slip an old nail or a blade in for you, and you could use it to escape.” A little light, a little hope because he was beginning to realise why he was in this box, there could only be one reason. He was to be sent aboard a brownbone to wherever those who were to be sacrificed in the cause of the boneships went.

To die, that he was ready for, had been ever since he was condemned. But to go into the foetid hold of one of those ships, in a box like this? No, that was more than he thought he could bear.

Gueste leaned in a little closer. “You Berncast fool,” she said, and all hope died. “Take comfort that though you are a traitor, you serve a greater purpose. Your Berncast blood can do some good now, rather than simply dirtying up the deck of a fleet ship’s rump. Even a dead ship deserves better than you.” Joron tried to speak but his throat burned, his lips betrayed him. “You really think you can simply sneak out without being seen? You think you can meddle without others being aware?”

How foolish he felt – that he had thought he shared some kinship to this woman, sat and talked with her as if they could be friends. Not even considered that she may be there to spy upon him and all those in the hagbower.

“If you had any idea how much you are hated, Twiner, a Berncast officer raised on the whim of a disgraced shipwife, you would never show your face in this town, ever.” She leaned in closer. “I know, you must be a little worried about your future, Joron. So let me give you a gift, a little positivity. I am born to the Bern, and born to the slate of a ship, and we guard our places jealously. There is nothing we hate more than an interloper, and putting you in this box has fixed more than a few bridges I may have previously burned. So, while you go to forward the cause of the Hundred Isles, in the best way for your kind, so shall I. I am to get my own ship.”

“Gueste,” he gasped out.

“Shh, shhh,” said Gueste, “save your energy for the journey, Twiner. You will need it. It is a kindness I do you, really, for I have seen the marks of the rot are already upon your skin.” And then she withdrew and the lid was shut, locking him back into darkness. Joron struggled, straining his muscles against his bonds and more than anything he wanted to give voice to his terror.

But he could not scream.

He. Could. Not. Scream.

What Mevans Did

Now Mevans was an old sea hand with all the experience and cunning such a thing brought. He knew many a thing, and one of those things he knew many things about was officers. He had particular, and very certain, beliefs about officers. He knew that when it came to directing a ship and directing a battle and formulating a tactic and such things, an officer was as fine as the Mother’s breasts, but he also knew that without a crew to look after them, an officer was often likely to trip over some Maidentrick as would never gull a sensible fellow like Mevans. And as such, it did not sit well with him to leave his deckkeeper behind to make his own way back to Tide Child, as Mevans believed it entirely likely that his deckkeeper would fall off a harbour or some other such foolishness.

Though he had been given an order.

But Mevans was an old sea hand with all the experience and cunning such a thing brought. He knew many a thing and one of the other things he knew many things about was orders. He had particular and certain beliefs about orders. Now an order was to be carried out to the letter, and he had been ordered to take the information he had back to Meas and to wait there for the d’keeper. To many, this would seem a right specific order but Mevans was not so sure, and he felt it important that before he return to the ship, he clarify with his fellows just what they thought this order meant in the most exact way.

“I say,” he said, drawing them into a dark alley by a small drinking hole that served the cheapest and fiercest shipwine in the whole of Bernshulme, “it does not sit right to leave the deckkeeper all alone in that place, not with knowing what it is we know.”

“What is it we know, Hatkeep?” said Farys. Oh, he liked her, she were a quick one, with all the savvy a good deckchild needed to get ahead and make sure the ship ran fleet.

“The truth is, Farys, I cannot rightly be telling anyone what it is we know and I am not so sure it is a thing I should know myself. But it is as foul as the Hag all hungover, worse maybe.”

“We was ordered though, by the deckkeeper,” said Anzir. “To go back.”

“That is indeed right and proper what we were ordered,” said Mevans, for as said, he had particular and certain beliefs. “But he did not say to us that we should do it with all speed.”

“Hatkeep,” said Farys. “If what it is you know, and cannot say as it is right terrible, will the shipwife not be put out if we tarry?”

“Maybe; that can happen and I will handle her if it does. See, I reckon, Farys, that he has said, we must take the message back to the Child, and wait for him. And I also reckon, that as long as we are the ones to set foot on the deck first, then we will have obeyed that order, to the letter.”

There was some chatter then, as Anzir, Hastir and Farys discussed the matter between themselves and Mevans, as the highest ranking, stepped away to let them talk.

“We have decided, Hatkeep,” said Farys at last.

“And what is it you have decided?”

“Well, Hastir, who was once an officer, says we have been given an order and should follow that order and though she knows the d’keeper did not specifically say go straight back, that is what he meant and it being so that is what we should do.”

“I see,” said Mevans, for he did.

“But now, Anzir, she says it sits bad with her to leave the d’keeper for she is honour bound if he may be in danger to help, and she says we should go and check on him.”

“I see,” said Mevans, for he did. “Well, Bowsell Farys,” said Mevans, “it appears you have the casting vote here.”

“Ey,” she said. “Well, though I have no doubt that Hastir is right and the d’keeper did mean us to go back, as it sounds like what it is you know is right important, I wondered if only one of us could go back?”

There were nods of agreement from Anzir and Hastir. But Mevans shook his head.

“No, that cannot be,” he said. “For that is as good as saying we know what we was ordered to do and decided not to do it. No, it is an all-or-nothing deal, the interpretation of an order by a deckchild, see.”

Farys gave him a short, sharp nod. She did indeed see.

“Well then, Hatkeep Mevans,” she said, “I cannot in good conscience . . .” He felt a deep disappointment within at those words, that Farys was not made of the stuff he thought. But he had thought too soon. “I say,” she continued, “I cannot leave the d’keeper if he may be in trouble.” Mevans’ disappointment immediately turned to elation.

“Shall we go and speak to the hagpriest then, Hatkeep?” said Anzir. “She will take us to Twiner.”

“I fear she will not, good Anzir, not at all, for she has taken a right dislike to us. We must go in the back, through the bay where they bring in and out the goods. I am sure a few rough fellows like us will be right at home there.”

“Can we not go back to Meas, and tell her we think the d’keeper is in trouble?” said Hastir.

“Ey, we could,” said Mevans, although he knew, for him, even knowing what he knew, that he could not do that, for he had come to right like the new deckkeeper. And more, he had seen a brownbone drawing into the harbour under the cover of night, and had a terrible feeling – not a knowledge, just a deckchilder’s feeling, the same way he knew a storm may be over the horizon – that he knew what that brownbone meant for those within the hagbower.

So they made their way, not to Tide Child as the deckkeeper had instructed them, but back to the hagbower which, although it appeared to vanish into the mountain did no such thing. It snaked its way around beneath the earth and emerged further down the mountain on the other side, in a small yard at the end of a long road which eventually ended at the harbour. Mevans, in the way he believed any good deckchilder should if they wanted to as much as call themselves fleet, had reconnoitred the area on the first day when his deckkeeper had not shown his face. And, in the way he believed any good deckchilder should if they wanted to as much as call themselves fleet, he had picked out places from which they could watch the small courtyard and all the comings and goings of the women and men who serviced the hagbower.

He led them through the town and out of it, until they found the rear of the hagbower and a vantage point in the vegetation above the loading bay behind. The first thing that Mevans noticed was that the place below was peculiar in its set-up. He took for granted that those with him also noticed, for they had not just walked off the stone and onto the deck of a ship that day and, truthfully, would he, Mevans, Hatkeep to none other than Lucky Meas herself, bring anyone with him who did not know their business?

No, he would not.

“There is a lot going on down there, but not many people doing it, Hatkeep,” said Farys.

“Ey,” he said, and oh, she was a clever one.

“Makes me think what is going on is secret,” she said, and oh yes, she would go far.

“Ey,” said Mevans.

“Is it not odd, Hatkeep,” said Hastir, “that they are loading up something heavy, but not unloading nothing heavy from those wagons?

“Ey,” said Mevans, and it was. Wagons, drawn by tall

gillybirds, were coming up the hill and rather than unloading barrels of food and drink for the sick they unloaded long, low boxes. As Hastir had pointed out, the boxes were clearly empty. The women and men carrying them did a poor job of pretending they were weighty as they took them in to the rear of the hagbower, but they were far more convincing when they brought them back out, stacking them two across two in little towers.

All except one box. Which was on its own to one side.

And it was this box that Mevans was most interested in. Not only was it stacked separately, but he’d seen a right stonebound-looking type, despite their fleet uniform, all full of her own swagger and of the type Mevans would have soon as thrown off a deck as trust on one, peering into that box for what was a peculiarly long time. Now, Mevans well knew how deckchilder became obsessed by the strangest of things: money, bone carvings, weapons; he’d even known a woman who collected the false legs of those she had killed. But something of that fellow’s demeanour struck Mevans as right conversational. And he did not think a woman dressed like a cockbird in its best plumage was likely to talk to an empty box, or one full of weapons or bone carvings or money or even false legs. Though he knew it may have been a little bit of a stretch, he was willing to bet his own favoured stinker coat, the one that he would let no other wear, that his deckkeeper was – for whatever reason, no doubt a bad one– in that box.

“Right, my crew,” he said. “That box down there, I reckon has our precious fellow in it, so before Skearith’s Eye is fully risen it’ll be bone knives at the ready and we shall go and get him. Do not be seen, do not raise so much as a chirp. Cut-throats is what we are tonight, and that will be our business.” The faces that greeted him were all smiles, for his girls and boys knew their business and their business was getting the deckkeeper back. “Now, Anzir, I count four round those big doors that go into the hill. You and Hastir will deal with them and then shut and bar the doors while Farys and I find the two who are roaming around those carts.”

So it was that four deckchilder, used to violence and danger and with all the skills that brings, tracked six women and men who were used to guarding carts and who were unaware that the pitiless gaze of the Hag had been turned upon them. And if the deaths were bloody, it can be said they were at least quick, for Mevans, Farys, Anzir and Hastir held no hate for these people; in fact, each was aware that given a twist of their tale by the Maiden it could have been them that guarded these carts. But they wished to see their deckkeeper put back in his proper place and would let no one stand between them. So knives were drawn, and flesh was neatly parted and the blood flowed.

When the deed was done the four deckchilder gathered around the box which Mevans had marked out.

“Well,” said the jaunty hatkeep, “shall we see what lies within our chest of treasure?”

And Joron Woke Again

There was no time within the box. No way of telling of the passage of Skearith’s Eye except the slowly growing pressure in his bladder. He had tried to listen for signs of others, that someone may come to help, but the more he listened the louder became the sound of his own breathing until it filled his world and he could feel the edges of panic gnawing at his mind. With every bump and scuffle he heard outside he imagined it was those who would carry him to his berth on a brownbone, from then to go in misery and confinement to his death. His imagination magnified every sound into nightmares until he resolved to listen no more. He simply lay, trying to push his mind from his body into some other place, somewhere that was not dark and hot and miserable and sure to end in death.

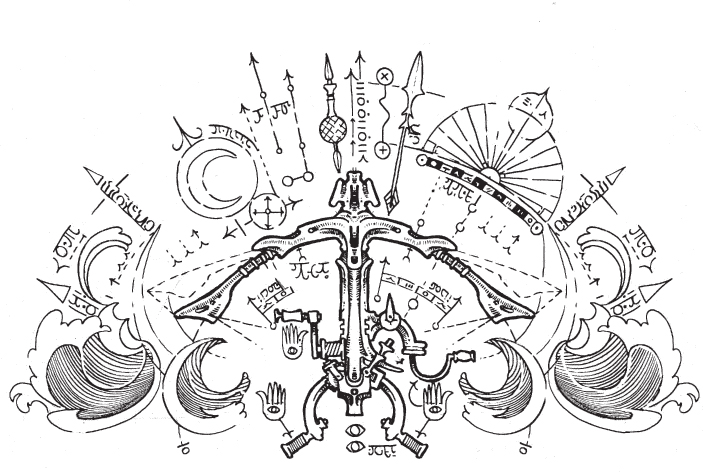

He did not quite know when the visions started, as they crawled in around the edges of his consciousness in subtle incursion. Nothing concrete, not at first, simply flashes of white light in the foreground of his closed eyes. Then the light took on colours, and the colours resolved themselves into shapes and he saw the vast and terrifying shape of Skearith the godbird as the Golden Door opened in the storms that walled the world and it came to rest upon a mountain. He heard the songs that had been with him since he had taken the gullaime to the windspire, but different, louder and stronger, vast and twisting. He saw these images as scrimshaw, moving scrimshaw carved into the bones of his mind. He saw visions of the Maiden, the Mother and the Hag, massive and awe-inspiring, hovering above the thousands of islands of the archipelago, and every line of these figures was in constant motion, as if being endlessly carved anew, lines of white on yellow bone, and he could not shake the feeling that all three felt nothing but pity for their people, scurrying about heedless of those below. He thought he heard the Mother speak – though she spoke with a voice that sounded uncomfortably like Meas – “They threw the spear that killed a god, and have learned nothing since.” He was overwhelmed by sorrow, the voice so loud and full of presence that it was forcing him from his own mind, crushing him away from sanity. He saw Hassith, who killed the godbird and shamed all men, as he threw his spear which pierced the eye of Skearith, loosing all sorrow.

He saw the hatching of the Maiden, Mother and Hag from the four eggs, saw the gift of the gullaime hatch from the fourth and something in him screamed that this was all wrong, and the song grew and grew in his mind until he felt sure he must go mad. The sore spots on his arms, legs and shoulders screamed into the night, linked through a burning fiery pain. Ghostly arakeesians carved in a white so bright they hurt his closed eyes now swum through the infinite darkness of his tight prison, burning their images onto the whorls of his brain and he knew no time nor awareness. He felt his mouth move, though he heard none of the words as he raved within his box, whispering words beyond understanding. He felt the cold of Garriya’s knife against his neck, and thought he saw some truth but it was fleeting and lost to him before he understood it. Meas talked of change, and yet he had never believed that, only followed her. But now, here, and too late, he had heard the words of the Mother and knew change was needed.

Or was that just the desperation of the doomed?

Light flooded in. Unready for it, he turned his head away, so he did not see the smiling face of Mevans, and as he had resolved not to listen he did not hear the shout of joy from Farys and Anzir when he was uncovered.

“Deckkeeper! Are you drugged, Deckkeeper?”

What was this, some new hallucination? But this one lacked the bright colours, lacked the squirming lines of knife on bone. He found words, forced them past the rawness of his throat and, though he meant to say the name of the man who stood above him, he did not.

“Water,” he croaked.

“Of course, D’keeper,” and Mevans had it already, the liquid caressed Joron’s lips, cooling his throat. Then it stopped. “Anzir, lift him from the box.” She did, huge, strong and gentle arms reaching in, first to cut the ropes that bound him, then to lift him from the wooden coffin and lay him on the ground as feeling and pain flooded back into hands and feet denied blood for hours on end. Joron found himself growling, an involuntary action to ward away the pain.

“Ride it,” said Mevans, “ride it Deckkeeper and listen to my voice.” Mevans’ hand took his, skin as hard as horn from hauling on ropes. Joron squeezed the hand tight as a wave of pain washed over him. “We must get you back to the Child,” he said, “Anzir and Hastir will carry you. If any ask, we will say you have had too much anhir, so act thus, ey?”

“I told you,” said Joron between sharp breaths, “to go back to the ship.”

“Ey,” said Mevans, his eyes opening wide in all innocence, “and we was indeed on our way when we happened to pass here and see a cock-fellow putting you into this box. And I said to Farys, we cannot be having that, can we. Farys?”

“No, said I, D’keeper,” added Farys.

“Well you see, and with these other two, being of the lower ranks on the ship, well, Mother bless ’em, they ’ad no choice but to do as they was told, right?” Joron closed his eyes, gathered his strength.

“Thank you,” he said. “Thank you.” Raised his arm. “Others . . .”

“Tsk,” said Mevans, “is only what is our job, you would have done the same. But, I am afraid time is not on our side, and well, we have made rather a mess so it is best we get away. Can you walk, enough to play drunk?”

“Others,” said Joron again quietly. Mevans stared into his eye. “The other boxes.”

“We are only four, D’keeper,” he said. “Truly, I am sorry, but we must leave.”

Joron nodded, knowing what they said was right, and breaking a little inside at the thought of any others trapped in the boxes stacked behind the hagbower. His little crew guided him through Bernshulme, apologising for their drunken friend all the way. The only odd thing that happened was as they went up the gangplank to Tide Child, Joron noticed that Farys, Anzir and Hastir hung back while supporting him, as if they wanted to ensure that Mevans was the first back aboard and Joron could not, for the life of him, work out why.