39

The Calling of Joron Twiner

His throat hurt.

His throat hurt and they were all going to die.

The forest creatures filled the air with song and noise and they were all going to die.

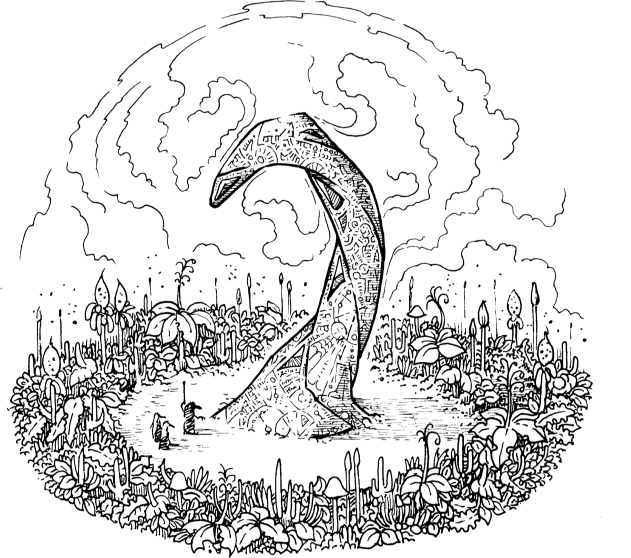

The air was full of the thick, sweet and earthy smell of the gion forest decaying, the life leaving the forest like the life had left his vocal cords. Dying the way all those around him would die, because he could not do what was needed. It did not matter that he was unsure of exactly how he had brought the tunir from the ground that day, because the only thing he actually knew was that he had used his voice, his beautiful lost voice, to open the ground. And his voice was gone, no matter how the song may sit within him; that twisting, winding, discordant and yet strangely pleasing song. The one fighting to escape from within him and join the throbbing chorus of the windspire. He did not have the tools to air it. Maybe the gullaime sang without vocal cords. Maybe it just did not understand how humans worked.

But he could not do it.

So they would die.

Farys would die.

Meas would die.

Berhof would die.

The gullaime would die.

Madorra would die.

He would die.

But what could he do? He was simply a damaged man among damaged people in a dying forest.

“Shipwife Barnt!” Meas’s voice. Louder than anything else as she stood balanced on the defences, despite the slipperiness of the gion stalks. “Shipwife, come to me! Talk terms to me!” She was buying him time, but what use was time to him? Joron rubbed his throat, as if the pressure of fingers, calloused with years of work on rope and wing, could force his vocal cords into working again. “Shipwife!” It was as if Meas’s shouts calmed and quietened the creatures of the dying forest, her last call echoing out into silence.

“What do you want of me, Meas?” A reply from the darkness. Joron squinted but could see no figure, became annoyed at this discourtesy, as discourtesy it was. To use her name rather than rank. And to remain hidden when a shipwife asked for terms was as much as saying you did not trust them, thought they may simply shoot you down if you appeared. It was to lump her in with raiders and brownbone shipwives.

“To talk,” she shouted. Joron felt a movement by him, saw Madorra had picked up the gullaime and was helping it shamble toward him.

“Why should I talk with you?” returned the voice.

“Terms, Shipwife,” replied Meas.

“Terms?” The tone amused, sardonic. “I think I need none. I think one more push and you are finished. The great Meas, beaten. And by a man at that.”

“Or not. I’m well known for turning the tide, have been doing it all my life.” Time, passing in the arrhythmic drips of the wilting forest. A figure emerged from the dark – tall and thin, well dressed in tight-fitting fishskin and a cloak of feathers.

“I think if you had some secret weapon or plan, you would already have used it.” Shipwife Barnt had a stick, a foolish affectation to drag through the forest. He also had Joron’s sword. “But I have heard rumours of your gullaime’s strength, and maybe that is why you try and delay my final push.” Joron rubbed on his throat as the man spoke. The gullaime and Madorra shuffled nearer to him. “I tell you what, Shipwife Meas,” said Barnt. “Bring me the head of your gullaime, and I will talk terms with you.”

“Our gullaime? But why? Such a creature is worth far more to you alive.”

“Do you think I hear nothing in Bernshulme, Lucky Meas?” He walked forward a step. “Do you think we know nothing of you?” Another step. “Do you think me a fool, Lucky Meas, the traitor?”

“I am no traitor. Our people are being taken to die and I would stop it.”

“Your people are being taken? Well, traitors deserve all they get.”

“You call me traitor,” she said. “When you side with those who take the weak and sick from the streets, and the hagbowers.”

Joron felt a pulling on his sleeve.

“A traitor,” Shipwife Barnt raised his voice, “will say anything. Don’t listen to her poison, my boys and girls. Sharpen your blades. Ready yourselves for the killing time.”

Joron looked down, saw his gullaime, its painted mask angled up at him.

“Wait!” shouted Meas. “Do you not want me alive, to take back to my mother?”

“Right enough, a fine prize you would make.” Barnt grinned. “But I have heard enough stories of you to know you would be nothing but trouble, Meas Gilbryn, so I’ll settle for your head. Much simpler all round.”

Joron listened while staring down into the masked face of the gullaime. It looked old, bent and frail, and it was clear that every movement hurt it. It reached up to him with a wingclaw.

“Very well,” said Meas. “My fate is sealed, and every woman and man who follows me knows what you do with traitors now, so they will not give up. The fight will be hard and to the last.”

“Life is hard and to the last, Shipwife Meas,” Barnt replied.

“Ey, that is true,” she said. “May we sing, one last time, Shipwife Barnt? May I lead my crew in song, for they have been loyal to me, and they deserve one last moment of joy.”

Barnt stared at her, then smiled and gave a small nod.

“What can one song hurt?” he said. And at that moment the gullaime’s wingclaw touched Joron’s chest.

“Song here,” it said. “Sing, Joron Twiner. Sing for her.”

And Meas lifted her shining sword and began to sing, a slow and low lament.

For every one who left

My dear

For every one who flew

For all aboard the ships

My dear

Lost, like me and you

And the crew joined in on the chorus:

The Hag she knows no pity

And the Maiden knows no love

And the Mother only duty

So I will be your warmth

The crew’s voices fell away, leaving Meas’s voice, loud and pure, to echo through the night.

To each who met the water

My dear

For every one who flew

To each who slowly sank

My dear

Lost, like me and you

And each and every crewmember stepped forward. To join their shipwife. And Joron felt a pain in his chest, a sharp wingclaw that pierced his shirt and cut into his flesh.

“Sing!” hissed the gullaime.

And Joron, with nothing left and no real hope of finding the tune, opened his mouth and tried. And what came out was not a tune, not a song. A single harsh cry. Like lone skeer flying over a stack of stone as the sea slowly beats away its base, inching it toward the moment it finally toppled into the sea and smashed apart in a last act of unwitnessed violence.

The Hag she knows no pity

And the Maiden knows no love

And the Mother only duty

So I will be your warmth

For the last verse no voices fell away but Joron’s. What had come from his mouth had been a blow to him – worse, in so many ways, than what he had expected. Barely even human. He closed his mouth. Only to feel that sharp pain in his chest again.

“Sing!” hissed the gullaime. He stared at it. “Sing!”

And he did. Though it pained him, and forced tears from his eyes, he found himself unable to disobey. He sang.

For all who man a bow

My dear

For every one who flew

For who dies upon the slate

My dear

Lost, like me and you

“Sing, Joron Twiner.” And was the gullaime’s voice, deeper, louder, stranger and stronger than he had ever heard it before? Did it echo like they stood alone in a cave? Did it surround him like he was entombed in rock? It did and it did not and he felt dizzy and pained. He felt strong and weak. He opened his mouth and he sang once more.

The Hag she knows no pity

And the Maiden knows no love

And the Mother only duty

So I will be your warmth

The song ended and they were left in silence, looking to one another. The lament had affected Joron the same way it had affected every other in this filthy, muddy, smelly clearing around the windspire. How sad it was to die here, having come so far for such a grand purpose, to save lives. How terrible for those taken from Safeharbour, who must dream that Meas and the Tide Child would come for them, but that dream would die here and they would never know how hard they had been fought for.

“A good song, Shipwife Meas,” said Shipwife Barnt. “An excellent choice for your last words, and I hope the Hag heard them.” He paused, as if he heard something in the gion.

A shiver passed through the melting tops of the giant plants.

A huge leaf came down with a crash and the animals of the forest set up such a cacophony Joron could barely hear himself think, never mind hear what the enemy shipwife was shouting.

Was the man commanding a charge?

The ground shifted.

Joron almost thrown from his feet by the sudden and violent movement. This was not like when he and the gullaime had called the tunir. This was something altogether stranger, stronger. Something bigger was happening.

The ground shook again, staggering all those in the clearing and shaking the forest around them.

“Run!” Meas’s voice. “All of you, run!”

“Don’t let them escape!” shouted Barnt.

Joron scooped up the gullaime and ran for the edge of the clearing. Women and men had been scattered by the sudden tremor and many had fallen – another tremor came as they tried to stand and it was all Joron could do to keep his balance as he ran. A woman tried to stop him and Madorra flew at her, sharp claw taking out her throat in a shower of blood. A man came at him from the right and Berhof was there, taking his blow on his shield and lashing out. Joron did not see if the blow landed, for he was running, slipping and sliding into the brown vegetation at the edge of the clearing. Concentrating on going forward. Another woman before him and he heard Cwell shout, “Seaward!” He swerved in that direction. A knife flew past and took the woman in the chest. Then he was in among the dying gion, pushing through slimy vegetation. Glancing up, just by luck, or fate, he saw the huge gion Meas had made them all memorise, black against a sky smeared with the sparkling wash of Skearith’s bones.

He paused.

Took a deep breath. Sounds of pursuit all around him. Bodies crashing through brush. Screams. Shouts.

He whistled. Heard answering whistles. Knew them for his people and he set off running again.

Beneath him the ground shivered and shook once more, as if trying to pull his feet from under him, making him stagger. He would have fallen but he had his crew now. Farys on one side, Berhof on the other, Cwell behind him and they steadied him, would not let him fall.

Shouting, all around them. The enemy. He glanced back and saw them, running pell-mell through the leaves, bashing them aside, whooping and screaming. There was joy in them. This was the killing time when your enemy were routed, when you cut them down from behind and lost yourself in blood and triumph.

“This way,” shouted Farys, and led him landward, using her small body to push aside the brown vegetation.

Leaves lashing his face, vines slippery underfoot. They broke into a clearing. Five enemy deckchilder there who had somehow got ahead of them. They smiled, raised weapons. He stopped. There was nothing he could do. The gullaime filled his arms. No time to drop it and draw his weapon. Then pushed aside, violently. Cwell, a fury of lashing blades and screaming anger as she ran past him, crashing into the group. Berhof joining her, Farys next and the enemy were down.

“Run on,” shouted Cwell. “I will guard your back.”

They ran, on and on until they burst through into the clearing before the entrance to the cave. Found a fight. Not a big one – most had been drawn away from here by the battle at the windspire. Berhof, Farys and Madorra ran for the fight while Joron hung back. He stood in the middle of the clearing, the gullaime comatose in his hands, fighting to keep his footing as the shuddering of the island increased, the rock moaning and creaking like a boneship caught in a storm. He turned, saw Cwell standing at the clearing’s edge. As the cave mouth was cleared of its few defenders her gaze slid to the dark hole in the island. Then to Joron. She shifted her weight from one foot to the other, as if deep in consideration.

“Come on,” he said, as more of Tide Child’s crew broke into the clearing. She stared at him. Held his gaze. Then shook her head and turned away, running back into the forest.

Hag curse her. He had almost started to believe she had changed. Well the Hag could take her then, and Hag pity her if he ever found her in a fight.

“Joron!” Meas’s voice, calling from the cave entrance, flanked by Coughlin and Berhof. He ran, passing between them among the stream of Tide Child’s deckchilder. Watching Meas as she counted heads.

“How many made it?” he said.

“Not as many as I would like.” She glanced over his shoulder and into the clearing and he turned. Saw enemy deckchilder emerging from the forest.

“Go,” said Berhof. “With all this the movement of the island, I reckon I can bring down this entrance.” He nodded at the lintel of cured varisk, now splintered and fragile-looking. The island rumbled and shifted again and the lintel creaked.

“It will crush you,” said Meas.

“We can hold this passage you and I, Seaguard,” said Coughlin.

Berhof smiled and moved the arm that covered his midriff, exposing a wound, and the oozing flesh beneath. Joron could smell the acid of Berhof’s stomach, the sickly-sweet smell of ruptured guts, and knew it a killing wound.

“You go. I think I will stay.” A smile crept onto Berhof’s face. “Be glad not to get back on that Hag-cursed ship,” he said. The smile fell away, replaced by lines of pain. “It has been a good fight, Coughlin.”

“Aye,” said Coughlin and he stepped forward, grasped Berhof by the forearm, and pulled him into an embrace. Joron heard quietly spoken words. “I will see you at the fire, my friend.” Then they turned and were running again, down the tunnel beyond, into the island, and Joron did not know if the rumble he heard from behind was Berhof bringing the entrance down on himself or the island moving once more.