ROCKY MOUNTAIN GOAT—Lord of the Crags

The Short-Horned, Long-Haired Lord of The Crags is One of Our Most Under-Rated Big Game Animals!

This business of writing about hunting and guns isn’t all that easy. There are, after all, only so many ways to hunt deer and so many things to be said about the .30-06. Therefore I suppose we writers can be forgiven occasional flights of fancy in developing catchy titles and offbeat slants for what really are “business as usual” stories. I, of course, have been equally guilty.

However, over the years I’ve seen a number of writers (and/or helpful editors) try to stir up additional interest in a story about hunting the Rocky Mountain goat by calling it “the poor man’s sheep hunt.”

This offends me. It is true, thank goodness, that hunting our mountain goat on a guided hunt basis is far less expensive than sheep hunting. But does the phrase mean that the mountain goat is worthy of only a working hunter’s attention? That there is more worthy quarry for the wealthy? Or does it mean that the mountain goat is some sort of backward cousin to the more noble sheep? These premises and any extensions thereof are simply preposterous, and are a great disservice to both a superb game animal and those who might pursue him. Serious goat hunters—and there are a few—got a huge boost in 2001 when two British Columbian hunters were awarded Boone and Crockett’s highest award, the Sagamore Hill trophy, for taking the new World’s Record Rocky Mountain goat on a difficult and grueling self-guided hunt. This may create a bit more interest in hunting this beautiful animal!

Our unique Rocky Mountain goat is not a cousin to any sheep, backward or otherwise. He is a majestic and challenging trophy in his own right, and I consider it a blessing, not an indictment, that he can be pursued for a fraction of the cost of a sheep hunt. Unfortunately, since both Rocky Mountain goats and our American wild sheep are high country animals, some parallels must be drawn. In this regard, goat hunting is both more difficult and much easier than sheep hunting.

In good country goats are extremely prolific and can become quite plentiful. They are normally found above timberline and are relatively sedentary in their habits. Their year-’round white coats make them extremely prominent in the ledges and crags they prefer. These facts combine to make Rocky Mountain goats relatively easy to locate at long range, certainly easier than any sheep excepting Dall’s sheep before the snow flies.

It is also much easier to shoot a goat than it is to shoot a sheep—provided your goal is simply to shoot a goat. With goats there are no 3/4-curl or full-curl minimums nor a requirement to count annual rings. Under most circumstances both billies and nannies are legal game. This is probably because the horns of both sexes are quite similar; those of the nannies tend to be long and slender, while a billy’s horns are thicker. Both genders, however, carry short black daggers that curve back and slightly out from bases just above the ears. A difference in length of just two inches can separate mediocre from outstanding. Thus, if your desire is to simply shoot a goat, in decent country you can do this in a day or two of hard hunting and be done with goat hunting.

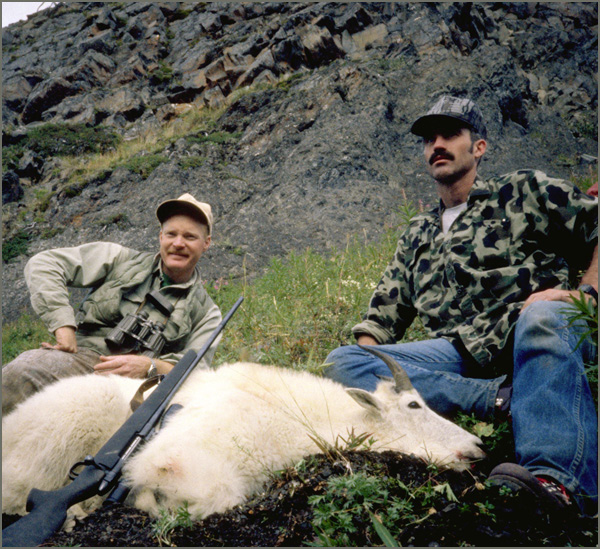

Such was my first experience with the Rocky Mountain goat nearly thirty years ago. The goat was part of a mixed-bag hunt in northern B.C. When it was time to get a goat we simply climbed up and got one. Mind you, it wasn’t all that easy. In fact, it was probably the most physically demanding day I’d spent hunting up to that point in my career—and I was young and in great shape, fresh out of Marine Corps officer candidate school.

This was in late August, when the goats’ pelage is short, patchy, and ugly. The result of that day was a particularly long-horned nanny goat. Despite the poor hide and the sex of the trophy, that remains a memorable day and its result a prized trophy. But many years passed before I really understood what goat hunting was all about.

If you want to hunt goats, and just perhaps take a fine goat—rather than just shoot a goat—the game changes dramatically. Goat hunting is then no longer just a difficult physical exercise, but a gruelling mental challenge as well. Here’s where goat hunting becomes more difficult than sheep hunting.

While it’s often far easier to locate goats, it’s usually more difficult to get to them. It’s axiomatic but true that goats live in rougher country than sheep. In fact, goats often live quite happily in country so rocky, steep, and treacherous that sheep will not—perhaps cannot—tread. Horses are a limited advantage in most sheep hunting; sooner or later you must leave them and eventually you must come back to them. In goat hunting that “sooner” is often much sooner!

If you can reach them and, preferably, get above them, then goats are usually not all that difficult to approach. Among their high crags they are confident in their security and a close stalk is likely. But that’s a big “if.”

Goats subsist on much rougher forage than sheep. They don’t need the grassy basins and can make do nicely on the sparse but nutritious grasses and forbs that grow among the rocks. Especially the older billies may spend virtually all of their time on narrow benches or ledges, never revealing even a clue as to how they got there or how—if—they ever leave their sanctuary. Two factors must be considered in planning a stalk on a goat. First, how to get there safely. Second, how to recover the goat safely. Sometimes the first condition is impossible to meet; the second often is.

In the summer, when the rocks are dry, goat country is steep and treacherous. Later, when the pelts are most prime, those rocks are frozen and deadly. Common sense and sound judgement must be applied when planning a stalk, and it must be thought through all the way. Sometimes you can approach to shooting range, but if you shoot the goat you can’t get to it. And if you can get to it, can you get yourselves and goat back out? Often you have to walk away. Or, rather, you have to climb away, for only rarely are the obstacles so obviously insurmountable that no stalk is attempted.

If it doesn’t work one way, perhaps you can try a different approach. Or perhaps you can wait in the hopes the goat will move to a more accessible spot. Sometimes they will, but often you’re better off looking for a goat you can reach!

Whichever, only common sense can mitigate the very real dangers of goat hunting. Never go it alone, especially in an unguided situation, and don’t let goat fever push you past your mountaineering capabilities. I’ve been stuck for long, horrifying minutes, unable to go up or down—and I’ve felt my feet slide on icy rocks with nothingness inches away. I always carry an ice axe on mountain hunts these days, and on late hunts crampons make sense—but it’s far better to stay out of situations where you might need either, let alone climbing ropes and pitons.

That’s getting to the goat. The next, and possibly larger question, is exactly what kind of goat you’re getting to. Oreamnos americanus, the Rocky Mountain goat, is a unique genus and species found only in the mountains of western North America, naturally from the northern Rockies and coastal ranges on north to southern Alaska. He has been transplanted, and has done very well, as far south as Colorado and Nevada, equally well on Kodiak Island. The heart of his range and the bulk of his population is found in British Columbia’s mountains and adjacent southeast Alaska, but northern B.C. seems the limit of the goat’s ability to withstand northern winters. Just a few extend up into the Yukon and the Mackenzie Mountains of Northwest Territories.

The mountain goat is not a true goat of the Capra genus, but rather a rupacaprine, or goat-antelope, somewhat similar to Old World animals such as the European chamois and the goral and serow of the Himalayas. Note, however, that he occupies his own unique genus with just one species; like the American pronghorn, he has no close relative on this or any other continent.

There is a great disparity in physical size among individual goats, but a large billy can exceed 300 pounds and will seem much larger in his flowing winter coat. The horns are small, which probably accounts for his second-rate status among trophy hunters. A billy with eight-inch horns is minimally acceptable. A nine-inch billy is perfectly shootable. A ten-inch billy is fabulous. And of course the nannies have horns as well, and virtually all goats have horns in relation to body size. These factors combine to make the Rocky Mountain goat the most difficult of all North American animals to judge. I’d be lying if I said I was good at it—and so is anyone who claims to be foolproof at judging goats!

The charm—and heartbreak—of goat hunting is you must get close to be certain. There are, of course, long-range indicators of sex and size. Herds, especially with young ones, are unlikely to have trophy billies among them—but if there is a big billy temporarily in a family herd he will dwarf the rest. In general, though, mature billies are likely to be in twos or threes or solitary, and they’re likely to be in higher, rougher, more inaccessible crags than the nanny herds. Typically a billy will have a slightly off-white, yellowish cast to his coat, and the billies will come into long winter coats well ahead of the nannies.

These clues will make you climb a mountain for a closer look, but they aren’t definitive. The horns are, of course, but the horns are the very devil to judge. Yes, the billies have heavier bases—but heavier in comparison to what when you’re looking at a lone animal of unknown size from several hundred yards away?

When push comes to shove, you must be very close to be certain both of sex and size. The best way to be 100 percent certain is to see the black, pad-like glands at the base of the horns. Both males and females have this gland, supposedly used to mark territories. However, the gland is much more prominent in billies and, at close range, will be visible—whereas, in nannies, the horn glands are concealed by hair. To see this feature you need patience and good optics—and you’d better be close.

With most open-country game, certainly with sheep, you can make a sound shoot/don’t shoot decision long before you’re in rifle range. On a calm day with a decent spotting scope you might decide that a ram meets your standards from a mile away, but certainly at a half-mile. The selection is made and the stalk is simply closing the deal; when you reach your shooting position, be it 30 or 300 yards, all that remains is a last-minute check to make sure you have the right animal. This is not so with goats. At distance you will have subtle indicators of size and sex, but it’s a mistake to anticipate a shot at the end of a stalk. First you have to get close. Once you’ve closed in and you can see the black pads at the horn bases then it’s time to get serious about final evaluation of the horns.

How close you must get depends on optics, terrain, weather conditions, and of course how particular you are. A goat hunt is one of the very best places for a variable-power spotting scope with an upper range of 40 or 45X. Twenty power really isn’t enough past a couple hundred yards—but in the mountains it’s a rare day when it’s calm enough to really use extreme magnification. The approach is to plan a stalk that will bring you within 200 yards—all the while understanding that then and only then will you make the final judgement and decide whether to shoot or walk away.

That’s the hard part. Reaching that decision point can be an agonizing ordeal, so much so that you can’t imagine doing it again the next day—or walking away without shooting. All too often the difficulty of the stalk takes over and a decision is reached long before you really see the goat. That can work out okay; a lone, seemingly big-bodied, yellowish-hued goat will probably be a good trophy. But not always. Been there, done that. Get close, make sure—and regardless of how hard the stalk, retain the mental toughness to walk away if you aren’t sure. You’ll be glad you did.

There are, of course, worse things than walking away or shooting a goat with an inch less horn than you’d hoped for. One morning, from our camp in a sheltered valley, we glassed two billies moving along just below a big face literally miles above us. They were moving along the mountain in our direction, so we planned an intercept. After six hours of climbing we had them in sight, bedded on a little knife-edge ridge 500 yards below us. Both goats looked big, and in retrospect I’m sure both were Boone and Crockett quality. One was slightly bigger than the other. There was little cover, so I inched my way down alone, slipping through deep snow. At 300 yards one billy spotted me. They both stood up, ready to bolt into thick cover below. Exhausted and winded, I sat down in the snow and just plain missed the larger goat.

A half-hour later, after I’d climbed back up to my guide’s perch, I threw up. Me with my normally cast-iron stomach. Whether it was over-exertion, something bad in a sandwich, or sheer frustration I’ll never know. I was deathly ill all that day and all through the night. The next day, pale and unsteady, I climbed the same mountain and shot a fine billy.

Ten inches of horn isn’t much for all that effort, but with a goat you have a lot more than just the horn. The coat is spectacular, especially if you hunt later when the winter coat is coming on. In fact, the winter coat of a big billy is a trophy at least equal to whatever horns he happened to grow. The long neck ruff accented by black horns and nose makes a stunning shoulder mount, but more so than any sheep I admire a lifesize or half-life mount of a Rocky Mountain goat. I’ve even seen them done as a stunning rug mount, head attached—but not for the floor. I wouldn’t want to trip and fall on those horns!

There is a down side to old Oreamnos americanus: his flesh is, well, “chewy but flavorful” is about the best I can do. A nanny can be pretty good, but a billie is just plain tough. Goat is edible, especially if well-marinated. But it sure doesn’t compare with mountain mutton!

Not only is their meat tough, but the goats are just plain tough critters. They also have a disastrous habit of heading for the ever-present precipice upon being threatened—including upon receiving a bullet. It’s important to anchor a goat in his tracks, and you simply should not shoot if he’s near a serious drop-off.

Goats are slab-sided creatures, and their toughness isn’t so much physiological as mental. The answer is not hard bullets for extra penetration. Just the opposite, in fact; goats require bullets of appropriate deer/sheep calibers that are heavy enough to break bone but soft enough to expand readily and do damage. Shoot for the shoulder and don’t hesitate to shoot again. If he can, a goat will dive for the nearest cliff with the last of his strength. At best he’ll make recovery more difficult. At worst he’ll ruin the horns and cape—or, worse yet, drop into a chasm where recovery is impossible. I’ve had two goats that were perfectly well-hit drop into chutes, but was lucky in that both hung up with no damage after short drops.

Something goat hunting has in common with sheep hunting is that it’s classic mountain hunting offering a fine excuse to wander through some of the prettiest country on Earth. But goat hunting somehow lacks the snob appeal of sheep hunting. This means, whether for good reasons or bad, you needn’t mortgage your home to hunt goats.

In the Lower 48 populations permits are limited enough that drawing a tag is every bit as difficult as getting a sheep permit. There are exceptions; both Washington and Montana have a lot of goats, and some units aren’t that hard to draw. But to plan a goat hunt without winning a permit draw you need to look farther north.

In both British Columbia and Alaska nonresidents are obligated to hire a guide, which increases costs considerably. However, there’s good news and more good news. First, due to inexplicably limited demand, guided goat hunts are quite reasonable, having escaped the runaway inflation of guided sheep hunts. Second, throughout most of B.C.’s mountain ranges and virtually all of southeast Alaska goats are an underhunted resource. Great billies die of old age each year—many, I suspect, without ever seeing a hunter. I hope it stays that way, for goat hunting is something I’d like to do more of while I’ve still got the legs and lungs for it. And not because it’s a poor man’s sheep hunt, but because the goat offers great hunting in his own right!