MULE DEER—Where Have all the Mule Deer Gone?

The Great Days of Mule Deer Hunting are over, But there are Still Great Mule Deer… If You Know Where to Look.

Dark was falling quickly, but not as quickly as the freezing rain mixed with thick, wet snowflakes. I was driving through northern Utah, and I happened to glance to the left at a little stock tank nestled in a sagebrush coulee. Just on the far side of the tank was a huge mule deer, the kind you dream of—thick, dark antlers, spreading wide and with clean, deep forks. The Utah season had just ended, and I was glad to see this buck. Glad that he had survived, and glad that his classic mule deer habitat still held such bucks. Unfortunately great bucks like him are no longer common today—certainly not in the Rocky Mountain high country, the core of what has always been the most classic mule deer range.

It’s hard to define exactly what many like to refer to as “The Golden Age of Mule Deer Hunting”—but for darn sure I missed it. The best years varied with the area, and the downhill slide was almost imperceptible at first. The early 1960s were probably the peak for trophy mule deer hunting across most of the West, but some traditional trophy country remained fabulous well into the 1970s. I could have gotten in on the bonanza, but mule deer weren’t a big thing to me thirty years ago. I was much more interested in elk hunting and saving up for a first African hunt; I never even attempted to hunt trophy mule deer until it was much too late.

The perception back then was that all you needed to do to bag a heavy-beamed 30-inch mule deer was show up in the right area and look around a bit. Chances are it was never quite that easy, but there was some reality in this perception. The Rocky Mountain West, the core mule deer range, was lightly inhabited and lightly hunted back then. Ski slopes and condominiums were few, mineral exploration was light, and elk numbers were low. While management manipulations have kept overall numbers high in many areas, the percentage of mature and old bucks that existed just a few decades ago will never be seen again.

In those days serious mule deer hunters had it good—and many of them now in their fifties and sixties still have the big racks to prove it. Nonresident hunters in numbers were a new facet of a more affluent and mobile post-war America. Casinos all across Nevada hosted “big buck” contests (some still do), and merchants all through the Rockies welcomed the hordes of hunters from the East and West Coast. Even the game managers got in on a little free enterprise; Utah was not alone, but she was a prime example of selling her deer herd. During the Golden Age you could fill a tag and go buy another . . . and another.

The decline was not an avalanche, but a slow downhill slide that continues to this day across the heart of the Rockies. Season by season the mature mossy-horned bucks became ever more scarce—and in many areas overall numbers have followed suit.

The reasons are not altogether understood—and since the cause is uncertain, the solution is less so. Part of the problem, especially in the reduction of mature, trophy-class bucks, has been overhunting—but only part. Human development, whether mineral, recreational, or urban sprawl, has blocked or destroyed much critical winter range. Then there are various experts’ pet theories: sagebrush eradication, unchecked increases in predators, the elk population explosion. Sometimes disease is a factor, like the chronic wasting disease that is a serious current problem. All have validity, with the real reason probably resting in some combination of factors depending on the area. Add drought or a killer winter to several of these other factors and you have a disaster requiring years to recover from.

A large part of the problem is politics. Thanks to those long lines of out-of-state autos (whose occupants aren’t so welcome any more, but whose dollars are) that converge on mule deer country each fall, mule deer became a cash crop with politicians unwilling to do anything that might interrupt the cash flow. But ever so slowly the reins have tightened. Arizona was the first western state to institute across-the-board deer tags-by-drawing. Wyoming and Nevada followed. Idaho and Montana established quotas. Several years ago, in an extremely unpopular, downright courageous, and absolutely essential move, Utah went to across-the-board drawings. Colorado finally crossed this inevitable line as well.

Limited permits are the present and future of mule deer hunting. It is unlikely to ever get easier to get a tag—especially in a good area. Nor is it likely to get cheaper. The new wave is to make more expensive tags more available—and not only on private land. In a weak moment I paid $500 for a “sure thing” 1996 Montana deer license—which makes one wonder where it can go. At least the tag drawings are fair to all, and they work. Nevada’s trophy bucks were badly depleted when she went to tag drawings, but in just a few years bucks of “4x4” or better formed the majority of the harvest. Drought has had its impact recently, but Nevada—seldom considered a hotspot in the “Golden Age”—remains fine trophy country today. I expect much of the traditional trophy country in both Utah and Colorado to recover, at least to some degree, given time and a conservative buck harvest.

Right now, however, and almost certainly for a long time to come, I consider a really large trophy mule deer—not necessarily a “book” deer, but a buck with mass, length, points, character, and class—the most difficult trophy in North America. It takes luck and persistence, but there are many places to bag a great whitetail. The way elk herds are exploding new elk hotspots are emerging every year. Sheep hunting generally means either an expensive hunt or beating the odds in a tough draw, but with enough money and/or a great tag wonderful sheep can be taken. Even with a great tag in the best remaining areas there are no assurances of a great mule deer.

And what are the best areas? Within “traditional” trophy mule deer country, roughly from the eastern front of the Rockies westward to the Sierras, there are very few hotspots. The remote Arizona Strip country, almost impossible to get into, still holds monsters among its few deer. Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau, though weather-dependent, continues to yield giants. Likewise Utah’s Paunsaugant Plateau, though perhaps it’s even more weather-sensitive. These are all permit areas, tough to draw (or, in the case of some Paunsaugant landowner tags, pricey).

New Mexico’s Jicarilla Apache Reservation, also expensive, continues to produce some giant mulies. Nevada shouldn’t be overlooked. Especially in western Nevada the buck/doe ratios are extremely high, genetics are superb, and the age class distribution is good. Southern Idaho was a real hotspot a few years ago. Notoriety and some bad winters have had impact, but good trophy potential remains.

Mind you, big mule deer are where you find them. The odd giant still turns up in western Colorado or western Wyoming, and that buck I saw in northern Utah was wonderful—but these days such bucks are increasingly few and far between. Fortunately the mule deer situation is a good deal brighter in many non-traditional and fringe areas. Perhaps only coincidentally, these are almost universally areas where elk are not a factor.

Mule deer are making and have made a wonderful comeback on the southern Great Plains, at least some of it due to carefully controlled permits. It’s a closely-guarded local secret, but western Kansas is producing some huge mule deer these days. Unfortunately this is mostly a playground for Kansas residents; the only nonresident tags in the best mule deer country are archery or muzzleloader.

Almost as good, and much more accessible, are the plains units in eastern Colorado. These are all draw units, with the best-known areas, such as the famed Purgatory in southern Colorado, requiring several preference points. But today you could encounter a monster mulie almost anywhere in eastern Colorado—and many of the units are a one-point or no-point draw.

I spent several falls both hunting and guiding in eastern Colorado, and it was very interesting. Our primary quarry was usually whitetail, but the mule deer were amazing. Many of us used to be concerned that whitetail would push the mule deer out—and this seemed to be happening in many areas. But at least in some of Colorado’s high plains the two species seem to be making peace with each other. One property we hunted is cut but by a winding north-south cottonwood-lined watercourse. Whitetails frequent the northern half, while the southern part of the drainage is almost all mule deer. Go figure!

It used to be that almost all hunting pressure in the region was on the more visible, more vulnerable mule deer. The current interest in trophy whitetails has actually taken a lot of pressure off the mule deer. On that particular ranch we posted a hunter overlooking a big hayfield one evening, and by last light he had 52 mule deer, including 14 bucks, in front of him!

An outfitter friend of mine, Mike Watkins, hunts country in northeastern Wyoming, southeastern Montana, and southwestern South Dakota. I’ve hunted with him a number of times—in all three states. All have an interesting mixture of whitetail and mule deer, but the mule deer are generally more numerous and there are good numbers of genuinely mature bucks throughout this region. Plains mule deer are typically smaller and lighter-antlered than the classic high country bucks, but given the chance to reach full maturity they can be exceptional. In the last few years I’ve seen great bucks by almost anyone’s standard. Perhaps more importantly, I’ve seen lots of nice, mature bucks that most of us would be very happy with.

Back in Colorado, but farther west along the foothills of the Rocky Mountain Front, the mule deer numbers are also very high. Much of this country is highly developed, a unique situation that I call “urban mule deer.” A friend of mine, Boulder attorney and outfitter Lad Shunneson, has leased and hunted a smallish ranch north of Boulder for many years. Houses have sprung up around and even on it, but that place remains the darndest buck funnel I’ve ever seen. Especially late in the season you can see big bucks—and different bucks—every morning and evening.

There are also some superb mule deer both north and south of what we think of as mule deer country. To the north, mule deer are coming back nicely in southwestern Alberta. This is undoubtedly due to limited outfitter permits and the current emphasis on whitetail hunting, but whatever the reason, given the chance to mature those Canadian mule deer grow huge.

The other oddball option is to the south, technically in desert mule deer country (subspecies Odocoileus hemionus crooki). Desert mule deer are smaller in body, but they can grow huge antlers depending on local food and genetics, and whether they’re left alone long enough. The situation is uneven, but I’ve seen great bucks in southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, and in west Texas as far east as Midland. Without question, however, the biggest desert mule deer—and some of the biggest mule deer currently available to hunters—come out of Sonora in Old Mexico.

Due to high demand and increasingly limited permits, this is an expensive deer hunt today, on a par with the Jicarilla or a private Paunsaugant permit. It is also not a sure thing; there aren’t many deer and the shooting is difficult. But the potential is fabulous. One of my best mule deer in terms of score came out of Sonora in the early nineties, and in January 2002 I took my first mule deer that achieved the magical “30-inch spread” that we all dream about.

This is a tracking hunt, and the Mexican cowboys are the best trackers I’ve ever seen—even better than the rightfully legendary African trackers. The desert floor, where the deer live, is brushy; the shooting is fast and quick decisions are essential. The trackers are great, but usually don’t speak much English—so you must be prepared to make up your own mind. Quickly. If you’re lucky you’ll shoot your buck in his bed—but more likely you’ll shoot him, or shoot at him, as he bobs and weaves through mesquite and cholla. Expect a chance at one great buck in a week’s hard hunting.

Like most great hunts this is not a sure thing. Hunting with various outfitters, I’ve taken three bucks in Sonora out of five hunts. This is pretty good, actually. In January 2002, hunting with Ernesto Zaragoza’s Solimar Safaris, we had six hunters in camp and we took seven mule deer (tags are private land tags, and a second buck is legal if tags are available) and two Coues deer. One buck, taken by Dwight Van Brunt, was spectacular. My 30-inch buck was good, and three other bucks were fully mature, heavy-antlered “keepers.” There were two mistakes, medium-sized bucks that should have been allowed to grow up—but things happen fast in the brushy desert, and sometimes you don’t get as good a look as you need.

Many hunters have concerns about travel in Mexico, but generally without justification. If you book with a good outfitter and follow his advice you should have no trouble. I’ve made many trips down there for both mule deer and Coues’ deer, and I’ve never had any problems.

We’ve covered my spin on the “where” of big mule deer today, but what is a big buck? Mule deer hunters, like moose hunters, talk about spread, but this is just one measurement. My 2002 Sonora buck was a typical four-by-four with eyeguards, decent points, good beam length, medium mass, and an outside spread of 31 inches. You wouldn’t pass him anywhere—but my buddy Dwight Van Brunt’s buck, taken on the same trip, was much better in almost all ways. His buck had more massive antlers, longer beams, and deeper forks; his buck makes the typical B&C minimum of 190 quite easily. Mine doesn’t come close—but my buck is a “30-incher,” while his has a spread of “only” 28 inches. Take your pick.

Thirty-inch bucks exist, but they aren’t common—and spread isn’t necessarily the most important factor if you’re into record book score. Mass and tine length count more, score-wise, and to my eye are more impressive. But the wonderful thing about trophy deer is that no two racks are alike, and beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Whether you’re a “spread freak” or not, the 30-inch mule deer is scarce nowadays—as are bucks that are big in all the other dimensions. These days a mature buck of 4 1/2 years or more with good mass, reasonable points, and a spread of 24 to 26 inches is a very fine buck. The chances are so slim today for a buck that will reach the Boone & Crockett minimum that I consider it foolish to even hunt for such a beast—unless you’re prepared for lots of disappointment, and of course unless you gain access to one of the few magical, mystical, and almost mythical hotspots.

Keep in mind that the vast majority of mule deer that do reach that wondrous score of 190 fall short of the 30-inch mark. Only two of the current “top 10” mule deer in the Boone and Crockett record book have an inside spread exceeding 30 inches—and the Number 8 typical mule deer, taken by Wesley Brock in Grand County, Colorado (in 1963, clearly a “Golden Age” buck), has an inside spread of just 21 4/8 inches!

But regardless of how they get there, mule deer that grow 190-plus inches of antler are both awesome and rare—whether you speak of gross or net. Unless you already have very nice mule deer trophies, an unlimited budget, an aversion to venison, or you like punishment, set your sights 10 to 20 inches lower today—and hope Lady Luck smiles.

After the “where” and “what” we should discuss “how.” This has not changed much. Excepting special circumstances like heavy oak brush or Sonora’s mesquite desert, mule deer are far more visible than their whitetail cousins. Glassing is generally the best technique, with early morning and late evening the most active periods. Mule deer are not as difficult to hunt as whitetails. The problem with big mule deer today isn’t that they’ve gotten more wary—it’s that there simply aren’t as many! However, the survivors, the ones that have lived to full maturity and grown those legendary antlers, aren’t exactly the pushovers of the 1960s. And, no, they don’t always stop to look back…

A couple of years ago outfitter Mike Watkins and I drove into a new ranch that was supposed to have some great deer. At dawn, enroute to the ranch house to “check in,” we passed a hayfield that was full of mule deer—mostly bucks. There were several “keepers,” nice plains deer, but we weren’t too excited—until we glassed a big-bodied buck at the far end of the field.

Oh, my! He was well outside his ears, very high, and very heavy. He was looking right at us, so we couldn’t count points. I assume he was a 4x4 plus eyeguards (which we could see), but he might have had small kickers. Whatever he was, he was a mid-180s frame, minimum, and if he had deep forks he was 10 inches better at least. He was the best mule deer I’d seen in quite a long time, and he was mine.

He was about 450 yards, but I had a laser range finder and a .300 Weatherby that would reach him. We never considered this most obvious option. We also never considered one of us staying to watch him. We had permission, so we could have done either. Instead, at my insistence, we played the game properly and went on to the house, said our “hello’s,” and launched a stalk around the back side of the field—which should have brought us to within 200 yards of the buck’s last known location.

We made the circle with the wind good, then crept up to the ridge overlooking the field. About the time we got there deer started to trickle out of the field, finished with their morning feeding. We viewed the procession for an hour—but the big buck was not among them. Non-plussed, we climbed to a high ridge that overlooked the field and system of sagebrush draws beyond. We had no trouble picking out the bedded forms of numerous deer, or recognizing deer we’d seen in the field and leaving the field. But the big boy was simply gone, and we never saw him again. So much for stupid mule deer.

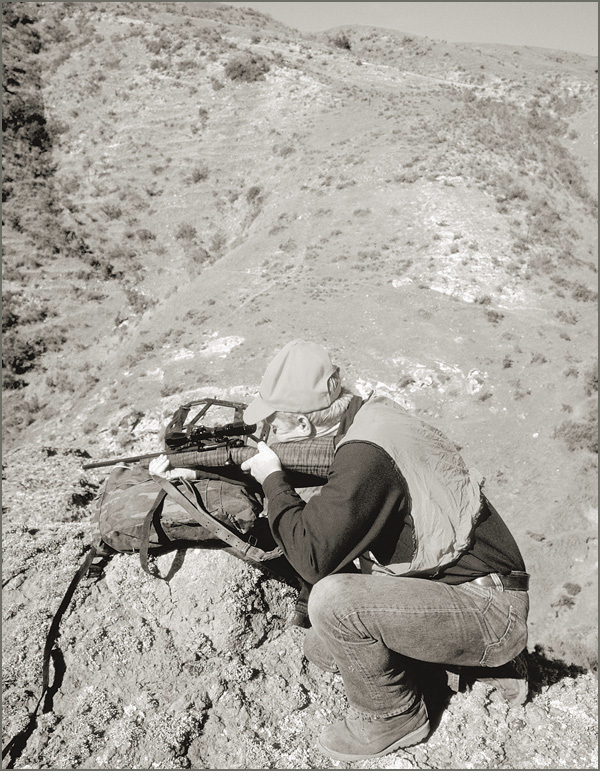

The best technique for mule deer is to get high and get comfortable and spend your time glassing with good optics. At any time of the season this is the best technique to locate a big buck. Obviously the chances are best during the rut, when even the older, more sedentary bucks are far more active and visible. In fact, a trick the late Jerry Hughes, a great Nevada outfitter, taught me is that during the rut you don’t even worry about finding bucks. Glass up a group of does and stay with them—for days if necessary. Sooner or later a big buck will show up. By the way, if the country is such that glassing is not an option, then the rut is not necessarily the best time to hunt. In Mexico, for instance, the cowboys can pick up good tracks at any time during the season—but during the rut the bucks are travelling, and they will generally have to follow them much farther. In tracking, the longer you must follow a track before the buck beds, the better the chance of losing the track. Even without tracking, prior to the rut bucks are much more habitual and easier to figure out—if you can find them—but when the rut occurs all bets are off.

Mexico and some of the thick oak-brush country are exceptions. In the main mule deer are open-country animals, generally visible and usually fairly vulnerable. If you can find them. The trick is to hunt where they are, meaning where the kind of buck you desire is present. Hunt patiently and with good optics and reasonable expectations. When you see something you like, move in decisively with cover between you and the animal and the wind in your favor. And don’t expect him to look back!