6

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE STREET

In previous chapters, I argue that film noir occupies a liminal space somewhere between Europe and America, between high modernism and “blood melodrama,” and between low-budget crime movies and art cinema. As an idea in criticism and as a market category in mainstream entertainment, the term has a similar quality; it describes both action pictures and “women’s” melodramas, problematizing the usual generic or gendered distinctions. Still other kinds of liminality are depicted in the films themselves. The stories frequently involve characters who have an ambiguous social position between the law and the underworld, or who seem in danger of losing their respectability and falling into a world of crime or madness. The action sometimes moves back and forth between rich and poor areas of town, or it takes place on a borderland—as in Touch of Evil, where an unstable, confusing boundary between the United States and Mexico becomes the locus of hysterical violence between nationalities, social classes, races, and sexes. In such cases, noir offers its mostly white audiences the pleasure of “low” adventure, having little to do with the conquest of nature, the establishment of law and order, or the march of empire. The dangers that assail the protagonists arise from a modern, highly organized society, but a society that has been transformed into an almost mythical “bad place,” where the forces of rationality and progress seem vulnerable or corrupt, and where characters on the margins of the middle class encounter a variety of “others”: not savages, but criminals, sexually independent women, homosexuals, Asians, Latins, and black people.

Radical film critics have responded to this situation in mixed fashion. In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, Anglo-American feminists analyzed film noir in two important and interconnected ways: as an instance of what Laura Mulvey calls the patriarchal mechanisms of “visual pleasure” and as a reflection of male hostility toward women in the postwar economy. The Hitchcockian eroticism of classic suspense movies was shown to rest upon a sadistic gaze that could sometimes become troubled and ironically self-reflexive but that ultimately served a perversely masculine need for social and sexual control; meanwhile, the misogyny of hard-boiled, pop-Freudian scenarios was made vividly apparent. Interestingly, however, feminists have been unable to agree about film noir’s specific sexual politics. This conflict is especially apparent in E. Ann Kaplan’s introduction to the influential anthology Women in Film Noir (1978), which points out that the various contributors share no single position “on whether film noir as such is progressive or not.”1 The problem of arriving at a broad agreement has something to do with the impossibility of defining film noir “as such,” but it also has to do with the inherently contradictory nature of Hollywood entertainment and with the in-between-ness of the films in question. As Kaplan points out, women characters in film noir are often evil, but because they are “central to the intrigue,” they take part in an important “ideological work” normally assigned to males (2). Some of the best-known noir narratives involve displacement of the patriarchal family in favor of lone wolves and spider women. Although the noir femme fatale is usually punished, she remains a threat to the proper order of things, and in a few cases, the male protagonist is “simply destroyed” because he cannot resist her charms (3). Hence a picture like Double Indemnity, for all its evident misogyny, usually leaves feminist critics in a position of arguing about whether the ideological glass is half full or half empty.2 As a moderator for these arguments, the most Kaplan can say is that film noir provides an intriguing “interplay of the notion of independent women vis a vis patriarchy” (3).

An equally mixed set of responses can be found in critical discussions of masculinity and homosexuality in film noir. Despite the fact that the Production Code of the 1940s explicitly forbade the depiction of homosexuals, the repressed “returned” in genres such as the horror movie or the psychological thriller, where implicitly gay characters were treated with a mixture of contempt and fascination. The novels of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were filled with latently homosexual situations (such as the odd relationship between Philip Marlowe and “Red” Norgaard in Farewell, My Lovely), and veiled stereotypes of gays were everywhere apparent in the crime pictures derived from those novels. In The Maltese Falcon, for example, the band of criminals is rather like a gay family, and in The Big Sleep, Humphrey Bogart imitates a lisping bibliophile. In many films, such as The Big Heat, the villain was a homosexual type, though he was never openly acknowledged as such. One of the most curious instances of Hollywood’s attempt to conceal the obvious is Laura, an unusually feminist narrative for its day, which casts Clifton Webb as a Wildean aesthete named Waldo Lydecker, but which asks us to view the character as a murderously jealous heterosexual who suffers from a kind of Pygmalion complex. Here and in several other important noirs, a covert homophobia is linked with a populist attitude toward social class: the villainous Lydecker is depicted as a parasitic dandy, in contrast to the more proletarian tough guy who is the hero of the narrative. Notice, however, that Lydecker plays an important role, and at some points he seems like the hero’s double. Merely by acting as the villain, he is a much more complex and significant presence than the equally closeted homosexuals in the average Hollywood comedy.

It would appear that the ideology of mainstream melodrama is threatened when women, artistic intellectuals, and vaguely homosexual characters appear as villains, or when the action takes place in an excessively “abnormal” milieu. This phenomenon has led Richard Dyer and several other critics to argue that the noir category in general expresses “a certain anxiety over the existence and definition of masculinity and normality” (Kaplan, 91). As Dyer observes, film noir “abounds in colorful representations of decadence, perversion, aberration, etc.” (Kaplan, 92), and its typically rootless, unmarried heroes provide a somewhat tenuous standard of normative masculine behavior. In many cases, the noir protagonist’s ability to serve as a role model is undercut by his quasi-gay relationships with men, by his masochistic love affairs with women, and by his more general weakness of character (see Gilda, Double Indemnity, and Strangers on a Train). Given such protagonists, Frank Krutnick concludes that 1940s noir deals with “traumatized or castrated males” who cannot function as the fantasy objects of an ideal masculine ego. The noir form as a whole, he says, is devoted to a “dissonant and schismatic representation of masculinity” and is “perhaps” evidence of a “crisis of confidence” in the male-dominated culture.3

Whether or not one accepts Krutnick’s argument about American society in the 1940s, it seems clear that Hollywood thrillers of the period tended to center on both male and female characters who were morally flawed, neurotic, or psychologically “damaged.” In a general sense, these films were attempting to inflect melodrama with what I have elsewhere described as an air of modernist ambiguity and psychological determinism. Influenced by American fiction during the 1920s and 1930s, they injected a degree of irony, antiheroism, and perverse violence into adventure stories, thereby expressing what Dyer calls an “anxiety” about normality. This does not mean, however, that they were inherently homophobic or misogynistic: as we have seen, Richard Brooks’s novel The Brick Foxhole, which was filmed in 1947 under the title Crossfire, is an explicit attack on homophobia, and a few traces of the original theme remain in the adaptation. Notice also that the noir sensibility strongly affected various forms of domestic or “women’s” pictures in the 1940s, undercutting the usual formulas. As R. Barton Palmer observes, Possessed (1947) and Cause for Alarm (1947) are somewhat different from an equally “psychoanalytic” but less noirlike melodrama such as Now Voyager (1942), because they do not provide a “compromised yet satisfying wish fulfillment—that is, the heroine put back in her place but offered a different, rewarding life.”4

Even when film noir is openly hostile toward women or homosexuals, it solicits the psychoanalytic and potentially deconstructive critical discourse that has grown up around it. Moreover, like other Hollywood formulas, it has depended upon contributions by female or gay artists. The only important woman director of the 1940s, Ida Lupino, was responsible for several movies that could be classified as noir, as were women writers such as Daphne du Maurier, Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Leigh Brackett. One of the most prolific American writers of noir fiction, Cornell Woolrich, was a homosexual, as were directors George Cukor and Vincente Minnelli, who were frequently drawn to noir themes or motifs. In our own day, there have been many examples of hard-boiled detective novels with female, gay, or lesbian protagonists, as well as a number of films noirs directed by women. In the latter group are Maggie Greenwald’s Kill-Off (1990), Kathryn Bigelow’s Blue Steel (1990), and Lizzie Borden’s Love Crimes (1992). The Bigelow and Borden films are intriguing applications of the “exchange of guilt” formula to women characters, but unfortunately their social criticism is undercut by a cliched and overly deterministic psychology.5 A much more interesting exploration of a similar theme is Captives (1996), a British production directed by Angela Pope, which offers a complex study of a love affair between a middle-class woman who has separated from her husband and a prison convict who has killed his wife. On a different level, consider Claire Peploe’s lovely tribute to Out of the Past in the comic, magical-realist production of Rough Magic (1997).

As we might expect, film noir’s treatment of race leads us to similar conclusions, for if noir is preoccupied with femmes fatales and homosexuals, it is equally preoccupied—and for many of the same reasons— with people of color. I have previously observed that movies of the type often depict Anglo protagonists who visit “exotic” places like Latin America and Asia or who frequent Harlem jazz clubs, the Casbah, and Chinatown. But film noir is not merely an occasion for whites to engage in racist fantasies. Noir flourished in America during the period between World War II and the beginnings of the civil rights movement, when a number of liberal and left-wing filmmakers were attempting to make pictures about racial prejudice and lynchings; moreover, when noir is viewed in a larger historical and cultural perspective, it is not exclusively the product of a white imagination. Virtually every national cinema in the world has made at least a few movies that fall into the category, and in the United States, many African-American writers have specialized in noir fiction. In recent years especially, African-American stars and directors have shown an interest in noirish conventions, thereby broadening the implications of the form and opening up the possibility for what Manthia Diawara has called “new and urbanized black images on the screen.”6

These racial, ethnic, or national issues have received comparatively little attention from critics, and I want to emphasize them here. Unfortunately, because the topic is so large, I shall need to limit myself to a few relevant motifs, gesturing toward the need for further work by other writers. In the following pages, I offer a brief historical survey of Asian and Latin themes in film noir and devote most of my critical attention to pictures that involve black people. I try to give a fairly comprehensive treatment of the topics I discuss, but I avoid theoretical speculation about the political or racial “unconscious” of noir. I merely want to observe several recurring patterns or themes, chart relatively obvious social changes, and offer a glancing commentary on the ways in which America’s dark cinema has both repressed and openly confronted the most profound tensions in the society at large. Although my remarks emphasize the racism and national insularity of Hollywood, my chief purpose is to show that noir, like the popular cinema in general, has a potential for hybridity or “crossing over”—a potential enhanced by noir’s tendency to create styles out of the mixed racial or national identities in the metropolis. The pictures by African Americans strike me as particularly good illustrations of this effect. By appropriating certain traditional formulas, such movies also reveal one of the most important and seldom recognized implications of the term film noir.

ASIA

The Shanghai Gesture, The Lady from Shanghai, Macao, The House of Bamboo, The Crimson Kimono, The Manchurian Candidate, Chinatown, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, The China Lake Murders, China Moon—these and other well-known titles would appear to suggest that film noir has a deep affinity with the Far East.7 The Asian theme can in fact be traced back to Dashiell Hammett’s earliest hard-boiled stories for Black Mask, which are saturated with a low brow Orientalism reminiscent of the Yellow Peril years before and after World War I. In “The House in Turk Street,” the Continental Op encounters a gang of killers led by Tai Choon Tau, a wily Chinese man who wears British clothes and speaks with a refined English accent. According to the Op, “The Chinese are a thorough people; when one of them carries a gun he usually carries two or three or more,” and when he shoots, “he keeps on until his gun is empty” (The Continental Op, 105). In “Dead Yellow Women,” the Op finds himself trapped on a stairway in the secret passageway of a house in Chinatown; below him is a beautiful girl with a “red flower of a mouth” and four Tong warriors reaching for their automatics; above him is a Chinese wrestler with “a foot of thin steel in his paw.”8

The Maltese Falcon involves a search for an Orientalist object, and the 1932 film adaptation contains a scene in which Sam Spade receives an important clue to the mystery of who killed Miles Archer from a resident of Chinatown. There is no equivalent scene in John Huston’s remake of 1941; but in the next year, Huston filmed Across the Pacific, a Falcon spin-off, in which Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor battle Japanese spies in Panama. This film was, of course, produced during World War II, when images of deceitful and violent Asians from earlier pulp fiction were easily incorporated into anti-Japanese propaganda. (The popular Charlie Chan series of B movies, featuring Anglo performers, remained in production throughout these years, but the Mr. Moto series, starring Peter Lorre, dropped from sight. The Moto pictures had been quite noirlike in their visual style; in fact, when Orson Welles saw Thank You, Mr. Moto [1937], he hired the film’s director, Norman Foster, to work on Journey into Fear [1942].)

If the Far East was repeatedly associated in film noir with enigmatic and criminal behavior, it was also depicted as a kind of aestheticized bordello, where one could experience all sorts of forbidden pleasures. Thus when Philip Marlowe visits an exclusive Hollywood nightclub in Chandler’s 1942 novel, The High Window, he notices a “check girl in peach-bloom Chinese pajamas,” who has “eyes like strange sins” (Stories and Early Novels, 1083). Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Gesture (1940), which Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton regard as a key work in the emerging noir “series,” is specifically about this theme of forbidden pleasure. The film was derived from a 1925 Broadway play that took place in a Chinese house of prostitution. To avoid problems with censors, Sternberg shifted the action to a gambling casino, but he intensified the atmosphere of exotic perversity, casting Gene Tierney and Victor Mature as Poppy and Omar, a pair of half-caste lovers who become connoisseurs of vice. Orson Welles’s Lady from Shanghai, which the director himself described as “an exercise in eroticism,” had a similar effect. A delirious mixture of misogynistic romance and dark social satire, the film stars Welles’s ex-wife Rita Hayworth as the Sternbergian temptress Elsa Bannister, who was born in Macao (“the wickedest city in the world”) and exerts control over a band of gangsters in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Propaganda images of sadistic Asians persisted through the cold-war decades, when China became communist and America became involved in a series of military adventures throughout the Asian Pacific. In The Manchurian Candidate, Henry Silva plays the evil Chunjin, a North Korean spy masquerading as a houseboy, who infiltrates the highest levels of Georgetown society and engages in a vicious karate fight with Frank Sinatra (a fight later parodied by Blake Edwards in the Pink Panther films). During the same period, however, the United States also wanted to put a human face on its Asian allies. American soldiers stationed abroad were marrying Asian women, and at home the civil rights movement was under way. As a result, Hollywood addressed the themes of interracial romance and marriage in such big-budget productions as Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955), Sayonara (1957), and South Pacific (1958). At almost the same time, low-budget auteur Samuel Fuller made a series of tough, unorthodox films involving Asian themes—among them, The Crimson Kimono (1959), a noirlike police melodrama that was far more daring than any of the pictures listed so far. The plot of The Crimson Kimono involves Los Angeles police detective Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta), who feels uneasy about his Nisei background and wants to assimilate into modern American life. During an investigation into the murder of a stripper, Joe and his partner, Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett), meet a beautiful young artist (Victoria Shaw), to whom they are both attracted. When the woman gravitates toward Joe, Charlie grows jealous, and the two men fight one another in traditional Kindo style. Throughout, Fuller plays interesting variations on the stereotype of Asian inscrutability, showing how all the characters fail to “read” one another. The personal story and the murder investigation are linked through the theme of sexual jealousy, and both problems are resolved after a documentary-style chase through the streets of Little Toyko at the peak of the Japanese New Year celebration. The film ends strikingly, with a kiss between Joe and his Caucasian lover.9

By this point, the moody Orientalism of the 1940s seemed passé and did not resurface in any significant form until Robert Towne and Roman Polanski’s retro-styled Chinatown, which once again associated the Asian district of an American city with mystery, violence, and perverse sex. However, one of Chinatown’s distinctions lay in the fact that it treated the old-fashioned motifs ironically, as a kind of white projection. The Chinatown street at the end of the film is not a center of evil but an oppressed ghetto controlled by the Los Angeles Police Department and the city’s ruling class; the story’s true perversity originates elsewhere— mostly in the dark heart of Noah Cross, who ultimately enters the Chinese community to kill off one of his children and to enclose another in his creepy embrace. Unfortunately, Chinatown’s many imitators tended to employ Asian titles or motifs merely to create an exotic atmosphere. During the 1980s, the most ambitious attempt to explore a Chinatown setting in the context of a thriller was Michael Cimino’s Year of the Dragon (1985)—a neogangster film starring Mickey Rourke, which offered a contemporary version of the old-fashioned Tong wars. By the end of the decade, as Tokyo became an economic rival of the United States, old stereotypes began to reappear in thrillers such as Black Rain (1989) and Rising Sun (1990), which reproduced the classic images of mystery and Eastern decadence, clothing them in sleek postmodern dress and giving them an air of liberalism by virtue of multiracial casts.

When we actually cross over to the perspective of films directed by the “other,” we can find plenty of noirlike elements but no Asian exoticism. The best examples of film noir in the Japanese art cinema have been two pictures by Akira Kurosawa: The Bad Sleep Well (1960), which fuses Hamlet with a Warner-style crime movie, and High and Low (1962), an adaptation of an Ed McBain policier, which makes brilliant use of wide-screen, black-and-white photography. At an entirely different level, the Japanese pop cinema is filled with cathartically violent genre pictures that have noirish settings or themes. One of the most flamboyant auteurs in this field is Seijun Suzuki, a B-movie contract director for Nikkatsu Pictures in Tokyo during the period between 1956 and 1967, who made bizarrely stylized movies about prostitutes and contract killers, somewhat comparable to the tabloid thrillers of Samuel Fuller (see, for example, Toyko Drifter [1966] and Branded to Kill [1967]).

In America, the Chinese-American director Wayne Wang’s Slamdance (1987) is filled with visual references to noir classics such as Rear Window and The Lady from Shanghai, although it has no specifically Asian themes. A much more interesting picture along these lines is Wang’s earlier, low-budget Chan Is Missing (1981), which employs an investigative plot structure and a style reminiscent of the early New Wave in order to depict a Chinese-American community from the “inside.”10 Peter Feng has described this picture as a “revisionist Charlie Chan film,” although he points out that Wang skillfully eludes any attempt to be pinned down with the usual terminology of generic classification, commercial categorization, or ethnic essentialism. Ironically, the success of Chan Is Missing in both art houses and video stores led Hollywood producers to offer Wang the chance to remake In a Lonely Place, a project he eventually rejected because the script contained “all American characters, except for one Asian.”11

More recently, Hong Kong cinema has been in vogue on the American market. One of the most artistically complex of these pictures is Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express (1995), which seems to be inflected by the French New Wave’s fascination with noir. Far more influential, at least in commercial terms, are the films of action director John Woo, who describes himself as “un-Chinese,” and who has become a major cult success. Woo’s highly stylized productions, such as The Killer (1989), synthesize generic conventions from Hollywood thrillers (especially the crime story motivated by revenge, guilt, or male bonding) with over-the-top flourishes from martial arts movies and Far Eastern musicals. I suspect that many of his youthful fans in America, not unlike Dashiell Hammett’s early readers, are indulging in fin de siecle Orientalism. In any case, his work in Hollywood has been largely confined to hard-body action films suitable to stars like Jean-Claude Van Damme, or to adventure spectaculars such as Broken Arrow (1995), which are designed for a worldwide market. Unfortunately, except in the karate-style fight sequences, these movies suggest very little Asian influence; the violence is less bloody than in the Hong Kong productions, and the action centers on the sort of swashbuckling trial by combat that Borde and Chaumeton regard as the antithesis of noir. Even in Face/Off (1997), where Woo employs many of the signature elements of his Hong Kong thrillers, the effect is relatively conventional. As Julian Stringer has pointed out, Woo’s non-Hollywood films are strongly affected by the recent history of China and are filled with an unusually melodramatic, “weeping” style of mas-culinity.12 Neither of these qualities can be seen in Face/Off, which transforms the noirlike theme of the “double” into a high concept for a pair of macho white male stars and weighs down the big-budget actions with clumsy, implausible exposition. At best, the picture appears to have been shot and edited by a mainstream director who was imitating John Woo.

LATIN AMERICA

Significantly, Woo’s Killer ends in a scene of melodramatic excess, involving fireworks and a bloodbath in and around a bizarre Christian church. The Christian symbolism in an Asian setting seems weirdly exotic, but in one sense it is merely an appropriation and reversal of the cultural semiotics in the typical Hollywood thriller. Notice how Chinatown employs a traditional Asian enclave to create a baroque, carnivalistic ending, in which the characters’ repressed passions come to the surface. A similar technique can be seen in many other Hollywood noirs involving Asian themes—for example, in the Chinese theater at the end of The Lady from Shanghai, in the amusement-park shootout at the end of House of Bamboo, and in the Japanese New Year at the end of The Crimson Kimono. But the atmosphere of carnival is not limited to Orientalist settings. Where noir is concerned, almost anywhere will do—the suburban U.S. town in Strangers on a Train, where Guy and Bruno fight one another on a runaway carousel, or even postwar Vienna, where Holly Martins and Harry Lime confront one another on a Ferris wheel. The point is to find a relatively festive locale that symbolizes the Place of the Unconscious or of psychological catharsis and gives the director sufficient opportunity to stage a spectacle. In Hollywood pictures, Latin American cities and villages have been especially useful for such purposes, because they can be so easily associated with baroque celebration. Hence we have the Day of the Dead parade and the tiovivo carousel in Ride the Pink Horse (1947) and the eroticized, Sternbergian carnival in Gilda.

During the 1940s, noir characters visited Latin America more often than any other foreign locale, usually because they wanted to find relief from repression. This phenomenon was no doubt overdetermined by various geographic, political, and economic factors: California’s proximity to Mexico; Hollywood’s support for the Roosevelt government’s “Good Neighbor” policy; the postwar topicality of stories about Nazi refugees in Argentina; the RKO-Rockefeller interests in Western Hemisphere oil fields; the general importance of Latin America as an export market; and so on. But it also had to do with the purely symbolic value of south-of-the-border settings, which provided a visual counterpoint to the Germanic lighting and modernist architecture in most varieties of dark cinema. In The Lady from Shanghai, for example, Latin America becomes the “bright, guilty place,” contrasting vividly with the dark skyline of Manhattan and the murky avenues of Central Park at the beginning of the story. And in Out of the Past, Jeff Bailey’s pursuit of Kathie Moffat takes him to a series of sun-baked Mexican towns that offer a temporary escape from the forbidding shadows of a northern metropolis.

The Latin backgrounds in classic films noirs take a variety of forms, ranging from the sleazy border crossings in Where Danger Lives (1950) and Touch of Evil to the sophisticated capitals and resorts in Notorious (1946) and His Kind of Woman (1950). Sometimes Latin America is indirectly evoked through California’s mission-style architecture, as in In a Lonely Place (“Sorta hacienda-like, huh?” a hatcheck girl remarks when she sees Bogart’s apartment). Sometimes it is suggested in nightclub scenes, as in Mildred Pierce, when a singer imitates Carmen Miranda. In the darkly claustrophobic Double Indemnity, it hovers about the edges of the narrative like the perfume that Phyllis Dietrichson tells Walter Neff she bought in Ensenada, where people drink “pink wine” instead of bourbon. No matter how the Latin world is represented, however, it is nearly always associated with a frustrated desire for romance and freedom; again and again, it holds out the elusive, ironic promise of a warmth and color that will countervail the dark mise-en-scène and the taut, restricted coolness of the average noir protagonist. In Double Indemnity, Fred Mac-Murray almost escapes to Mexico; in Raw Deal, Dennis O’Keefe tries unsuccessfully to escape to Panama; in In a Lonely Place, some of Humphrey Bogart’s most disturbing scenes with Gloria Grahame are set off against a framed reproduction of a Diego Rivera painting; and in Ride the Pink Horse, the embittered war veteran played by Robert Montgomery finds brief refuge by hiding in the tiovivo carousel.

Interestingly, many of the classic films noirs were made during a time of increased racial tensions in the Latin communities of Los Angeles. The Sleepy Lagoon case of 1943, in which a group of Chicanos were framed for the “Lover’s Lane” murder of a white couple, may have been an indirect influence on Joseph Losey’s postwar, social-realist thriller, The Lawless, and later on Welles’s Touch of Evil. For most filmmakers, however, the Latin world was imagined as a place located on the other side of the country’s borders. Notice also that when classic Hollywood’s noir characters traveled to Latin America, they took all their neuroses with them, and in a sense they never really left home. (This effect was heightened by the fact that Hollywood movies tended to use foreign settings merely as decor, staging most of the action on studio sets.) In Notorious, the Rio enclave of Nazis and U.S. spies is situated apart from the city, which is glimpsed in a few postcard views and functions as a sensual backdrop for a network of jealous obsessions among foreigners. In Gilda, the Buenos Aires casino is owned by a Nazi, and it bears a strong resemblance to the European-U.S. nightclub in Casablanca. In His Kind of Woman, Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell find themselves in a Baja California resort that looks as if it had been designed by Frank Lloyd Wright; the resort functions as a playground for rich Yankees, and the Mexicans themselves are in evidence only as strolling musicians or bumbling cops. And in Out of the Past, there is a moment when a corner of Mexico suddenly becomes New York: “There’s a little cantina down the street called Pablo’s,” Jane Greer says. “It’s nice and quiet. A man there plays American music for a dollar. You can shut your eyes, sip bourbon, and imagine you’re on 59th Street.”

These half-seen, barely experienced Latin locales give a picturesque quality to the films and perpetuate stereotypical images of passionate lovers and quaint peasants. In at least two cases, the Latin background heightens the sexy aura of Rita Hayworth, whose real name was Margarita Carmen Cansino. It also enhances the feeling of sophistication in films that are already imbued with an urban sensibility; the 1940s were, after all, a period when Latin and Afro-Caribbean motifs were all the rage in café-society nightspots like the Mocambo and the Trocadero, and when dances like the samba and the rumba were popular among the upper classes. Hollywood’s vision of Latin America was therefore largely confined to a melange of sentimental pastoralism and chic primitivism. Even so, the movies were careful not to associate the ownership of casinos and nightclubs with Latin Americans (usually the owner is a fascist émigré or a deported gangster), and they occasionally hinted at Yankee imperialism. Welles’s Lady from Shanghai and Touch of Evil are especially notable for the way they show rich northerners using the Latin world as a kind of brothel and for their brief glimpses of poverty on the Mexican streets—a theme that was much more evident before Columbia reedited the first picture.

In the 1960s and 1970s, when Latin America became a battleground between socialist revolutionaries and the CIA, some of the more romantic imagery of Latin countries began to temporarily disappear from U.S. screens. At the same time, urban life in the United States was being increasingly Latinized. Los Angeles in the years between 1920 and 1960 had the highest proportion of native-born white Protestants of any major city in the country; but after 1960, there was a great influx of Latino and Chicano Catholics. This phenomenon was repeated in other metropolitan centers of the Southwest and Florida, to the point where certain politicians demanded that a wall be built around the southern U.S. border and that English be established as the official U.S. language. Perhaps Hollywood was equally nervous about the population change. The new demographics are barely noticeable in the original release print of the futuristic Blade Runner (1982), which is set mostly in L.A.’s Chinatown and expresses a deep ambivalence about aliens or hybrids. (As Rolando J. Romero points out, the prerelease version featured a character played by Edward James Olmos, who provided a kind of synecdoche for the Chicano population.)13

The population growth in certain cities of North America eventually led to new kinds of noir settings. One of the most significant developments was the emergence of “Miami noir,” a term that applies equally well to Body Heat, the Miami Vice TV show, and Blood and Wine (1997). Unfortunately, few pictures in this vein have made significant use of Latin characters. Almost the same thing might be said of the Miami-based, hard-boiled fiction of Charles Willeford and Elmore Leonard, who have not been adapted as often as one might expect. During the 1980s, Jonathan Demme and Fred Ward produced an intelligent film version of Willeford’s Miami Blues, and Jackie Brown, Quentin Tarantino’s adaptation of Leonard’s Rum Punch, was released as this book went to press. So far, the best movie derived from Leonard’s Florida novels is the lightly comic and not terribly noirlike Get Shorty (1996). (The protagonist of this last film is a Miami gangster named “Chili” Palmer, but he is played by John Travolta. Other important details are treated in similarly cavalier fashion; when Palmer makes a charming and admiring speech about Touch of Evil, he gets most of the facts wrong.)

The situation today is all the more ironic because, as I note in chapter 1, Latin America has a strong tradition of film noir: consider, as only two examples of many that could be listed, Julio Bracho’s Distinto amanecer (Mexico, 1943) and Jorge Ileli’s Mulheres e Milhões (Brazil, 1961), the last of which has many things in common with The Asphalt Jungle and Rififi. Such pictures usually represent the Latin world as a dark metropolis rather than as a baroque, vaguely pastoral refuge from modernity, and as a result, they indirectly reveal a mythology at work in Hollywood. Two of the more effective recent examples include Foreign Land (1995), a Brazilian-Portuguese coproduction directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, and Deep Crimson (1997), a Mexican remake of The Honeymoon Killers (1970), directed by Arturo Ripstein. Both of these films are sharply attuned to the noirlike themes of moral culpability and doomed love, and have more poetic resonance than most of the neo-noir features from Hollywood. Unfortunately, we have no Latino versions of such North American “border” films noirs as Border Incident, Touch of Evil, The Border (1982), and Lone Star (1996), all of which center on racism and economic exploitation in the Southwest. The closest approximation is Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi (1992), a comic, “wrong-man” thriller, in which everyone except the Anglo villain speaks Spanish.

Meanwhile, the classic implications of the Latin world have tended to reappear with little modification in Hollywood neo-noir. In Body Heat, the sultry femme fatale is last seen on a beach in Rio, reclining next to her Latin lover. In The Wrong Man (1994), repressed sexual tensions break out among a group of North Americans traveling in Mexico. In The Juror (1996), a chase begins in New York and ends in a remote Guatemalan village during a carnival; the concluding scene shows the heroine (a single mom who designs postmodern art) gunning down the psychotic bad guy (a Mafia hit man with sophisticated artistic taste) inside an ancient Mayan temple, assisted by villagers wearing carnival masks. Elsewhere, especially in gangster movies, the South American drug lord now rivals the Italian mobster as a favorite villain—a trend established by the remake of Scarface (1983), which smoothes the transition from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean by casting Al Pacino in the role of a Cuban. In such pictures, Latin America continues to be represented in the form of a garish nightclub. The only difference is that the place is filled with colored light and is supposed to be owned by the Latins themselves.

AFRICA

The first private eye of the pulps, Carroll John Daly’s “Race” Williams, made his debut in a story called “Knights of the Open Palm,” which was published in a special Ku Klux Klan issue of Black Mask. (Lee Server points out that Daly, who was a relatively clumsy writer, at least had the distinction of authoring one of the anti-Klan entries.) Notice also that one of Raymond Chandler’s earliest stories, “Noon Street Nemesis,” originally published in Detective Fiction Weekly in May 1936, is set almost entirely in a black section of Los Angeles. When the story first appeared, the editors of the journal deleted all references to the race of the characters, but Chandler made sure that the deletions were restored for the reprinted version, “Pickup on Noon Street,” in The Simple Art of Murder.

Perhaps more importantly, the complex plot of Chandler’s 1940 novel, Farewell, My Lovely, is set in motion by ex-con Moose Malloy’s killing of a black man in an all-black bar on L.A.’s Central Avenue. The investigation of the crime is assigned to a worn-out white policeman named Nulty, who does nothing. Even Philip Marlowe, who twice uses the word nigger in casual conversation, seems resigned to the fact that the murder of black people is of no concern to the legal system. As the novel proceeds, other corpses (belonging to the white race) pile up quickly, and it is easy for most readers to forget the first death. In a sense, however, the neglect of the black man is precisely the point. Chandler’s major theme is that “law is where you buy it,” and the novel as a whole is designed to illustrate that crime is treated differently in different areas of town. During a period when high-modernist fiction was usually centered on the isolated consciousness of middle-class characters, Chandler used the lowly private-eye formula to map an entire society; and in Farewell, My Lovely, he shows that crime on the lowest social level of Los Angeles is on a single continuum with crime on the highest level. Hence the evocative opening chapters of the book, which give us closely observed pictures of a black community on Central Avenue, are linked by cause and effect to the later chapters, which take us to Jessie Florian’s decrepit house on West 54th Street, to Lindsay Marriot’s smart residence above the Coast Highway, and to Lewin Lockridge Grayle’s stately mansion near the ocean. We also meet a series of detectives who represent different constituencies: the ineffectual, incompetent Nulty, who works in the poorest district; the sinister Blaine and his dull-witted partner “Hemingway,” who are the hired minions of the gangsters and con men in Bay City; and the intelligent, persistent Randall, who investigates crimes for Central Homicide.

This social geography was not entirely lost in the Scott-Dmytryk-Paxton film adaptation of the novel, entitled Murder, My Sweet. Indeed the Scott unit at RKO had been established for the purpose of making social-realist movies. However, given the Hollywood censorship code and the racial climate of 1944, it was impossible for RKO to show the police as corrupt or to put Chandler’s original opening on the screen. The film therefore devises a sinister scene in a police station, which looks vaguely like a third-degree interrogation, and it shows Moose Malloy breaking up a working-class bar filled with white men in hard hats. Not until 1975, in the Dick Richards version of Farewell, My Lovely, did the movies attempt a reasonably faithful reproduction of what Chandler had written, but even then, Hollywood seemed nervous about the tone of Chandler’s work. The Richards film is only mildly critical of the cops, and it insists that Moose Malloy killed the black man in “self-defense.” It also turns Philip Marlowe into an overt liberal who befriends an interracial couple and their small son.14

The idea that blacks and whites might be brothers under the skin had already been suggested more indirectly on the first page of The High Window, the novel Raymond Chandler wrote immediately after Farewell, My Lovely. Marlowe encounters a lawn ornament in front of Elizabeth Bright Murdock’s pretentious house in the Oak Knoll section of Pasadena: “a little painted Negro in white riding breeches and a green jacket and a red cap,” who looks a bit sad, as if he were becoming “discouraged” from waiting so long. Each time Marlowe enters or exits the house, he pats the ornament on the head, and occasionally he speaks to it. During his initial visit, he turns to the figure and says “Brother, you and me both” (Stories and Early Novels, 988). On his way out after first meeting Mrs. Murdock, he mutters, “Brother, it’s even worse than I expected” (1002). At the end of the novel, one of his last gestures is to give the ornament a farewell pat.

For some readers today, a joke of this kind may seem condescending; but the lawn ornament tells us everything we need to know about the ruthless, repressive Mrs. Murdock, and it helps to establish Marlowe’s class position as a paid servant of the vulgar rich. (For a manifestly racist treatment of black people in hard-boiled literature of the period, see the novels of Chandler’s contemporary Jonathan Latimer.) Furthermore, there is an intriguing historical circumstance that makes the comparison between Marlowe and a black man not entirely inappropriate. The heyday of tough-guy realism, which produced Chandler, James M. Cain, Horace McCoy, and the other white writers whom Edmund Wilson describes as “poets of the tabloid murder,” was also a major period of social-protest literature by African Americans, and the black social-protest novelists— especially Richard Wright and Chester Himes—were intensely and necessarily preoccupied with murder and mean streets. Wright’s Native Son and The Outsider were plotted like thrillers, and so was Himes’s If He Hollers, Let Him Go; in fact, as Mike Davis points out, Himes’s skillfully crafted early work could be placed among the finest examples of Los Angeles noir, offering a “brilliant and disturbing analysis of the psychotic dynamics of racism in the land of sunshine” (43).

Himes was rarely discussed in such terms during his lifetime, but at the suggestion of Marcel Duhamel, editor of Gallimard’s Série noire, he eventually became a successful writer of tough detective fiction. In the years after the war, French critics saw a connection between the white tough guys and the black protest writers, who could be assimilated into a left-existentialism that Jean-Paul Sartre and many of his followers believed was at the very heart of the American novel. Hence both groups were given a cultural acceptance in France that they had not fully received in the United States. Significantly, Wright himself was living in Paris, and The Outsider, which he wrote during those years, has a good deal in common with Sartre’s own novel about crime, Les jeux sont faits. Himes, too, moved to Paris in the early 1950s, and most of his early crime novels were first published in French; his most commercial work was done for the Série noire, and he was the first non-French author to receive the Grand Prix de la literature policiere, which was awarded in 1958 for La reine des pommes ( A Rage in Harlem).

It would be wrong to fully equate either the hard-boiled school or the black social-protest novelists with European existentialism. The overwhelming sense of alienation, entrapment, and paranoia in Wright’s and Himes’s fiction rises out of a relentless social fact rather than a Kafkaesque abstraction, and the somewhat similar themes in the white writers can be traced back to the main tradition of naturalism and social realism in the American novel. But even though the three distinct cultural formations have separate histories, they share a common ground. The tough school of literature and film is filled with motifs that can be explained in vaguely existentialist terms; and as Roger Rosenblatt observes, the single place where “modern black and white heroes come closest to each other in terms of common atmosphere and situations is in the literature of the existentialists.”15 Wright and Himes therefore might have had as much to contribute to the French discourse on film noir as Chandler and Graham Greene.16 If they did not, the reason is that Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s did not adapt black novelists, or even show many black characters on the screen.

Most films noirs of the 1940s are staged in artificially white settings, with occasional black figures as extras in the backgrounds. The African-American writer Wanda Coleman has commented on this phenomenon in an article for The Los Angeles Times Magazine (17 October 1993), in which she also admits that she loves to watch old thrillers on TV. “Nothing cinematic excites me more than film noir,” she remarks; even so, there often comes a moment when her suspension of disbelief is shattered. The black Pullman porters, musicians, shoeshine boys, janitors, maids, and nightclub singers in these films are created out of a narrow range of stereotypes, and they painfully remind Coleman that, “like murder, the cultural subtext will out”: “My husband groans and my son laughs. Someone black has suddenly appeared onscreen. My stomach tightens and I feel the rage start to rise.…To enjoy that sentimental journey back to yesteryear, I have to pretend I live in a perfect world.…I have to force myself back through the door, back into the movie” (6).

Some black players in the 1940s were treated in relatively dignified ways, in part because the movie industry and the U.S. government were attempting to liberalize race relations during World War II. But in the era before the full-scale civil rights movement, film noir made no overt attempt to criticize the segregated society, and it never presented anything from a black point of view. Even a breakthrough actor like Canada Lee, who gave impressive but rather Uncle Tomish performances in Lifeboat (1944) and Body and Soul (1947), was never allowed to appear in a film version of his greatest stage role, as Bigger Thomas in Orson Welles’s 1940 production of Native Son.17 Welles, in fact, was the one white director in the period who might have made racial blackness more consistently and disturbingly present for white audiences. His incomplete documentary, It’s All True (1942), was abandoned by RKO largely because it paid too much attention to the black population in Brazil.18 At about the same time, he wanted to produce a film based on Native Son, but the project was much too controversial for the studios. For similar reasons, he was forced to put aside his fascinating adaptation of Heart of Darkness—which, had it been produced in 1940, would probably be regarded today as the first example of American film noir.

As we have seen, Conrad’s novella was already a kind of roman noir, and it served as an inspiration for Graham Greene’s thrillers, especially The Third Man. Welles’s screen version would have updated the African materials in the original text, placing the opening narration against the background of a sound montage and a series of dissolves that took the viewer through contemporary Manhattan at night, ending with a Harlem jazz club. When the action moved to the Congo, the exploitation and murder of the black population would have been carried out by modern-day fascists. “This shouldn’t surprise you,” one of them says. “You’ve seen this kind of thing on city streets.”19 RKO executive George Schae-fer wrote to Welles that the script “[lost] something” because of these references to contemporary politics, but Welles’s proposed method of shooting the film was equally troubling.20 He intended to use an expensive, mobile camera equipped with a gyroscope, and he organized his technically detailed, camera-specific screenplay in terms of long takes representing Marlow’s point of view.21 Where the politics of spectatorship were concerned, the technique was especially controversial, because it so often brought the viewer and Marlow into face-to-face contact with black characters.

To fully appreciate what Welles’s screenplay achieves, we need to understand that he did not plan to make a mere recording of what the narrator sees, as in Robert Montgomery’s unintentionally comic Lady in the Lake (1947), or as in the opening sequences of Delmer Daves’s Dark Passage (1947). The camera he describes is impressionistic and subjective in a more complete sense, often showing us what Marlow thinks or feels. Like Conrad’s prose, it is capable of shifting its focalization within a single take, moving from literal point-of-view shots to poetic omniscience—as when it suddenly tracks backward out of the manager’s office in the Congo Station, tilts down to look at a sick man on the floor, passes through the front entrance, cranes over the roof to show the jungle beyond, and then tilts up to a starry sky. Ultimately, it creates a kind of white dream or hallucination about blackness, and one of the many reasons why it might have been effective on the screen (contrary to what most people have said) is that, unlike Chandler’s Marlowe in Lady in the Lake, Conrad’s Marlow is a relatively passive and highly imaginative witness. Welles never treats the camera as an action hero who is periodically socked in the jaw by a gangster or kissed by a gorgeous woman; instead, he gives us an eerie narrative presence who stands by and watches, occasionally being confronted by grotesque sights and sounds. His script describes a bewildering variety of characters who bob in and out of the frame, and it is filled with precise instructions for a delirious, overlapping dialogue that helps to convey Marlow’s mounting confusion and disorientation. The uncanny effect would have been enhanced by a sophisticated, expressionistic use of process screens, showing bizarre images of the journey downriver toward the Central Station. On a more immediate level, however, the camera would have administered mild shocks in the form of characters who sometimes look back at the lens, arresting Marlow’s attention and making both him and the ordinary white viewer feel slightly uncomfortable or self-aware. These characters would have included not only the dictator, Kurtz, and his minions, but also the Africans themselves. Soon after Marlow’s arrival at the Outer Station, for example, the script tells us that he sees a “big, ridiculous hole in the face of [a] mud bank. In it, frying in the sun, are about thirty-five dying savages and a lot of broken drain pipes. Into some of these pipes the natives have crawled, the better to expire.…As Marlow looks down, CAMERA PANS DOWN for a moment, registering a MED. CLOSEUP of a negro face, the eyes staring up at the lens. The CAMERA PANS UP AND AWAY.”

According to Frank Brady, Welles planned to hire three thousand “very black” extras, and he resisted all of RKO’s suggestions that he save time and expense by putting greasepainted figures in the distant background. Two of the black characters would have been especially significant: a solitary, “half-breed” employee of the European ivory traders (scheduled to be played by Jack Carter, the star of Welles’s Harlem stage production of Macbeth), and an extremely dark-skinned woman who is Kurtz’s lover at the Central Station. The half-breed is described as “an expatriate, tragic exile who can’t remember the sound of his own language,” and he is repeatedly given the opportunity to look Marlow in the eye. The dark woman is seen only once, near the end, when she stands on the bank of the river, looking toward Marlow and stretching out her arms in grief. Here and elsewhere, relatively marginalized black people provide important dramatic moments—as when one of them looks at the camera and makes the famous announcement, “Mister Kurtz, he dead.”

All of the black characters in Welles’s film are racial stereotypes, and the script as a whole never escapes from the ideological contradictions at the heart of Conrad’s story. As Patrick Brantlinger observes, the original novella “offers a powerful critique of at least certain manifestations of imperialism and racism, at the same time that it presents that critique in ways that can only be characterized as imperialist and racist.”22 Where the film is concerned, Welles’s liberalism is frequently undercut by his use of primitivist and racist fantasies. Notice, too, that his camera would have represented a mixture of three exclusively white subjectivities: an “average” male in the audience; the fictional Marlow; and Welles himself, who not only plays Marlow but also, in the manner of Citizen Kane, fills the story with autobiographical details. Even so, Heart of Darkness would have been unique, providing the only occasion in the history of classic Hollywood when the white gaze was troubled by a returning black gaze and the imaginary spectator was made sharply conscious of racial difference.

By comparison, the ordinary run of films noirs in the 1940s made black people almost invisible, like the briefly glimpsed figures who carry Walter Neff’s bags or wash his car in Double Indemnity.23 Close-ups of these figures were especially rare, except in brief scenes involving jazz in such pictures as Out of the Past, D.O.A., and In a Lonely Place. There were, however, occasional attempts to give brief speaking roles to black people, and a conscious effort was made to avoid depicting them as the minstrel-show caricatures or comic illiterates of the 1930s. One scene in Out of the Past illustrates the new trend: Jeff Bailey visits a black dance club, where he locates Kathie Moffat’s former maid, Eunice, and asks her if she knows anything about Kathie’s whereabouts. The role of Eunice is acted by Theresa Harris, who had previously given a fine, unstereotypical performance in Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1942). She responds to Jeff’s questions without a trace of subservience, all the while conveying a wry intelligence. Her male companion (Caleb Peterson) is an unusually dignified presence—unsmiling, silent, and slightly on guard. The scene as a whole is played without condescension, and whether it intends to or not, it makes a comment on racial segregation.

FIGURE 58. Theresa Harris and Caleb Peterson in Out of the Past (1947).

Here and in several other films of the kind, black extras or bit players also give the protagonist an aura of “cool,” so that he resembles what Norman Mailer once described as the “White Negro.” This effect is especially apparent in Robert Aldrich’s 1956 adaptation of Kiss Me Deadly, which, as I indicate in chapter 4, seems to have a divided and somewhat incoherent attitude toward Mike Hammer. In some respects Aldrich criticizes Mickey Spillane’s hero, but in others he slightly revises the character, making him a relatively sympathetic embodiment of urban liberalism. Thus when we first meet Hammer, he is listening to Nat Cole on the radio; later, we discover that he is a regular customer at an all-black jazz club, where his friendship with a black singer (Madi Comfort) and a black bartender (Art Loggins) helps to indicate his essential hipness.

At about this time, Hollywood began to produce films that involved a full-scale “buddy” relationship between male blacks and whites, thus allowing the black actors to become true characters. The phenomenon originated as early as Casablanca, but it became a formula after the 1950s, influencing such postclassical, quasi-noir pictures as In the Heat of the Night (1967), Lethal Weapon (1987), and The Last Boy Scout (1991), all of which are instances of what Thomas Bogle identifies as the “huckfinn fixation.” Bogle remarks that, traditionally, “darkness and mystery have been attached to the American Negro, and it appears that the white grows in stature from his association with the dusty black.” Thus in the classic huckfinn scenario of the 1950s, a white male’s companionship with black people signifies his opposition to the corruption and pretense of bourgeois society and enables him to acquire a measure of “soul”; the important qualification, as Bogle observes, is that the black character “never competes with the white man,” functioning instead as a kind of “ego padder.”24 At first glance, the situation in Lethal Weapon is a bit more complicated, because the black character is portrayed as a middle-class suburbanite and the white character as a social outcast. The film reverses the usual structure of racial patriarchy, showing an alienated white man who is restored to health by a black father-figure; meanwhile, it depicts the black family in the utopian style of a television sitcom, surrounded by commodities and enjoying the comforts of the American dream. Notice, however, that the white male emerges as the true phallic hero—the “lethal weapon” who saves the black bourgeoise and maintains a traditional ideology. As Robyn Wiegman remarks, the film “allows the white figure to be healed by the same familial unit that he himself is responsible for preserving.”25

A much more intriguing reversal of the huckfinn relationship can be seen in Robert Wise’s much earlier, independently produced noir classic, Odds against Tomorrow (1959), written without credit by the blacklisted Abraham Polonsky. Operating on one level as an allegory about racial conflict, the film explores the deadly tensions that break out between three bank robbers: an aging ex-con (Ed Begley), a southern racist (Robert Ryan), and a black jazz musician who is also a compulsive gambler (Harry Belafonte). These last two figures are unwillingly bound together by the crime, but they never learn to cooperate with one another. Throughout, Wise and his collaborators are unsentimental in depicting the wounds of race and social class, and they create a number of impressively unorthodox minor characters—including a homosexual thug (Will Kuluva) and a sex-starved, pathetically masochistic woman who lives upstairs in Ryan’s apartment building (Gloria Grahame). At the end of the film, during the brief, failed bank robbery, Begley is killed, and the picture climaxes with a gun battle between Ryan and Belafonte, who chase one another across a series of oil storage tanks. When the tanks explode in a fashion reminiscent of White Heat (1949), the two men’s bodies are so broken and charred that an investigating fireman asks a police officer, “Which is which?”

FIGURE 59. The private eye as “White Negro.” Ralph Meeker, Madi Comfort, and Art Loggins in Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

In the years following the civil rights movement, films made by black people became more widely visible. Significantly, the first important commercial breakthrough by a black director in Hollywood was Ossie Davis’s Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), an adaptation of the Chester Himes’s roman noir about Harlem police detectives Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnston. In place of Himes’s sinister, subversive irony, Davis employs an old-fashioned ethnic humor, in much the same way that Hollywood in the 1930s tried to play Hammett and Chandler in broadly comic style. Partly as a result of Cotton Comes to Harlem, however, a truly radical transformation of black images suddenly appeared in 1971, when a pair of low-budget crime pictures directed by black men became surprise hits. Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song and Gordon Parks’s Shaft were grounded respectively in the themes of criminal adventure and private-eye fiction, but they gave new life to old forms by turning the black male into a sexually potent hero. Both had crossover appeal for young white audiences of the Vietnam era, and both were symptomatic of a broad countercultural reaction against liberal stereotypes. Of the two, the independently produced Sweet Sweetback was by all odds the most threatening; it gave full vent to separatist black rage, allowing its criminal protagonist (Van Peebles) to fulfill every nightmare of white society and to emerge unconquered. Shaft, which was produced at MGM, was a straightforward entertainment, accepting the legal establishment in the qualified manner of a typical private-eye movie. Its eponymous hero (Richard Roundtree) laughed at the law but was unwilling to join a group of black-power revolutionaries; he was also mildly cooperative with the one white policeman in New York who seemed not to be a racist.

FIGURE 60. Harry Belafonte in Odds against Tomorrow (1959).

One of the striking differences between these last two films and the standard noir thrillers of the 1940s was their refusal to depict the male hero as in any way flawed, compromised, or even vulnerable. Responding to decades of emasculated or nearly invisible black people on the screen, Van Peebles and Parks created black supermen, and they spawned a brief series of low-budget imitations that can be listed among the most phallocentric pictures this side of Mickey Spillane or James Bond. In one of the Shaft sequels, the hero tries to resist being typed as a sybaritic stud: “I’m not James Bond,” he insists. “I’m Sam Spade.” He nevertheless remains a Bond-like, leather-coated warrior who lives in a sophisticated Village pad and is irresistible to women. The hero of Sweetback is not only sexually prodigious but also downright ruthless, and he was clearly an influence on Gordon Parks’s next film, Superfly (1972), a highly successful criminal adventure featuring a slick cocaine dealer who dresses and behaves like a Harlem pimp.

Thomas Bogle observes that Van Peebles and Parks “assiduously sought to avoid the stereotype of the asexual tom,” but in doing so, they reproduced an equally old and distorted image of the “wildly sexual” black hedonist (240). They also tended to glamorize the dark side of town. Parks was especially good at photographing downtrodden New York locales, such as the porn movie theaters along 42nd Street and the gloomy alleys of Amsterdam Avenue, in ways that made the urban ghetto look pregnant with adventure. In fact, his neorealist color photography and night-for-night chase sequences had a strong influence on Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, thereby helping to establish a visual style for American neo-noir as a whole. Despite their broad influence and their escapist fantasies, however, Van Peebles and Parks could not be completely absorbed into the mainstream; their early work still seems refreshingly different from Hollywood, if only because of its rough, documentary texture and its unusually angry, rebellious tone.

By the 1990s, the black middle class had grown sufficiently to provide greater opportunities for black stars and directors; nevertheless, various forms of de facto segregation still existed, and the black underclass in the cities had reached crisis proportions. In the face of these circumstances, the urban thriller or policier emerged (for better or worse) as the form of popular movie entertainment that most consistently dealt with black issues. The two white directors who were most influenced by black film noir in the 1970s—Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino—showed an interest not only in black themes but also in the most powerful word in the English language. In Scorsese’s case, the term nigger is often spoken by Italian working-class characters who suffer from a racial inferiority complex and feel a compulsive need to identify themselves as white. In Tarantino’s, the effect is somewhat different. The gangsters and tough guys in Pulp Fiction use the term over and over again (along with bitch), while at the same time the film tries to protect itself against charges of racism by means of the plot and the casting: John Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson are linked together like Huck and Jim; Bruce Willis saves a black man from being raped by a couple of white southern racists; and Tarantino himself plays a gangster’s accomplice who is married to a black woman. Audiences probably respond to the racial epithets in mixed ways, much as they once responded to Archie Bunker on TV. Some liberal viewers may regard the repeated nigger as a daringly realistic gesture, or as an attempt to divest a repressed word of its ugly power; racist viewers, however, are likely to experience a secret thrill.

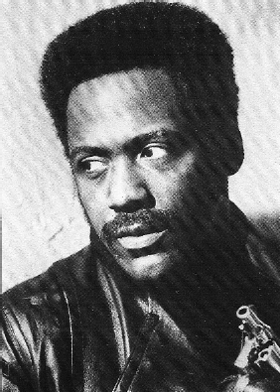

FIGURE 61. Richard Roundtree in Shaft (1971). (Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

If many of the old images of blackness persist in Hollywood noir, there is also a new kind of African-American presence. A wide range of hip-hop or “gangsta” films directed by African Americans depict a black criminal milieu in a fashion similar to traditional rogue-cop or caper movies, and the black actor Larry Fishburne has performed impressively in a series of ambiguous roles derived from classic noir—most notably as the undercover narcotics agent who is drawn to crime in Deep Cover (1992) and as the ex-CIA operative in Bad Company (1994). This chapter cannot do justice to all the recent “noirs by noirs,” and for that reason among others, I recommend Manthia Diawara’s essay on the topic in Shades of Noir (1993). Diawara uses Chester Himes as a paradigmatic African-American author of noir fiction, and he makes an important distinction between two types of crime movies by African-American directors: on the one hand are more-or-less-traditional romance narratives and gangster films such as A Rage in Harlem (1991) and New Jack City (1991); and on the other hand are realist, socially critical pictures such as Boyz N the Hood (1991), Juice (1992), and Clockers (1995). Both types combine noir motifs with rap music, but the socially critical pictures tend to appropriate the highly commodified youth culture and its associated black nationalism on behalf of “an ideology of black progress and modernism.”26

For my own part, I would note that two of the most impressive African-American movies about crime—Charles Burnett’s Glass Shield (1995) and Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress (1995)—avoid black nationalism and the new music almost completely. In most respects, these pictures are quite different from one another: The Glass Shield is a low-budget feature based on the true story of the first black sheriff’s officer in L.A. county’s notorious Edgemar station; Devil in a Blue Dress is a twenty-million-dollar adaptation of Walter Mosley’s best-selling 1990 private-eye novel, featuring star-performer Denzel Washington, who co-produced the film with the assistance of Jonathan Demme and other important Hollywood names. What the two movies have in common is a high degree of artistry, plus a tendency to refigure or transform the familiar patterns of noir. Both did relatively poor business in their initial theatrical release, but they remain worthy of serious attention.

The Glass Shield reverses the rogue-cop formula by centering on an idealistic young officer who is assigned to a rogue unit. The basic plot situation recalls Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973), but Burnett’s approach is expressionistic, bringing us much closer to the look of historical noir. The Glass Shield also has something in common with Mike Figgis’s entirely fictional Internal Affairs (1990), which pits a group of honest police detectives—a Latino, a lesbian, and a black man—against a corrupt white officer and his well-armed colleagues. Internal Affairs, however, is a slickly produced “psychological” thriller dealing with kinky sex and an exchange of guilt between a Latino good guy and a white bad guy. The Glass Shield shows no interest in doppelgängers, and it never indulges in subtly pornographic “entertainment values.” Moreover, its austere, beautifully controlled technique makes Figgis’s far more expensive production seem as empty as a magazine ad.

Burnett’s protagonist, John Johnson (Michael Boatman), is a token black policeman who undertakes his job at Edgemar with a youthful ardor. Even so, his colleagues treat him coolly or contemptuously. His only friend is Deputy Fields (Lori Petty), a former law student from Minnesota, who encounters abuse not only from the other officers but also from people on the street. Johnson and Fields quickly become disillusioned, and at virtually the same moment they realize that the station as a whole is guilty of excessive violence. The uniformed patrol unit, known as the “Rough Riders,” has a reputation for beating criminals; two officers are being sued for wrongful death in a recent case; and when Johnson is called to the scene of a robbery, he is ordered to stand outside a building while a group of club-wielding police and their attack dogs converge on an unarmed suspect in an empty room. Johnson himself participates in the dubious arrest of Teddy Woods (Ice Cube), a young black man who is stopped and searched without probable cause. and Johnson’s involvement in this case leads ironically to his expulsion from the force. In the film’s closing shot, we see him standing outside a courthouse with his fiancee, bashing a fist through his car window in frustration.

The Glass Shield nevertheless holds out some hope for justice. Moreover, unlike many examples of classical film noir, it treats Johnson’s family not as a locus of repression but as a relatively calm center of love and dignity. In a 1989 essay, “Inner City Blues,” Burnett places strong emphasis on this theme, denouncing entertainment movies—including movies by black directors—that deal with gangsters and “the worst of human behavior.” What America needs, he argues, is a socially conscious cinema that can give black audiences a sense of community and offer what he calls (not unlike Raymond Chandler) “an element of redemption.”27 The Glass Shield is therefore designed to suggest the familial, religious, and legal structure of a black neighborhood, showing how Johnson’s career isolates him from the people he most loves or respects—including his mother, his father, his fiancée, and the black priest and lawyer who struggle against white officialdom. Meanwhile, Burnett also depicts a diverse gallery of whites in complex terms: the intense Deputy Fields, who remains on her job a bit too long; the sallow-faced, expressionless Mr. Greenspan, who has probably murdered his wife; the sleazy yet somehow pathetic “Rough Riders,” who gather each week for a bowling game; the racist station commander, who breaks into tears when his unit gives him a deep-sea fishing rod for his birthday; the aging plainclothes detective in the Woods case, who continues to frame people even while he is dying of cancer; the slick young prosecutor, who expertly coaches the police on how to disguise their racism; the decent but frightened desk sergeant, who ultimately turns against his colleagues; and the woman judge at the Woods trial, who adopts a black child.

In these and many other ways, The Glass Shield is an impressive social commentary, but it would not be such a memorable film if it lacked Burnett’s subtly measured and dreamlike style. The opening shots, for example, juxtapose a comic-strip fantasy of Johnson’s life as a policeman with a flat soundtrack composed entirely of sirens and traffic noises. A series of drawings shows Johnson and Fields chasing down a couple of white thugs, with dialogue and gunshots rendered in bold lettering: “There’s no way out!” “Don’t try to be a hero!” “Kapow!” Johnson is wounded, and as the medics arrive, Fields holds him in her arms and announces, “You proved yourself. Your shield is made of GOLD!” From this panel, we dissolve to a live-action shot of an adventure comic pinned to the door of Johnson’s police academy locker. The camera pans to Johnson’s ecstatic face as he listens to an overhead loudspeaker calling his name and ordering him to report to Edgemar station. He seems euphoric, but the shot is photographed in slow motion, and it creates a bizarre effect: in the background, we can see an out-of-focus police cadet who is dreamily juggling a pair of nightsticks.

Occasionally, Burnett and photographer Elliot Davis employ the “mystery” imagery of classical noir. For example, in the scene in which Edgemar detectives question Teddy Woods, we see venetian blind shadows on the walls, and everything is shot from an extremely low level with a wide-angle lens. Elsewhere, the film makes use of tilted, Third Man camera angles—as when Johnson steps outside his front door and is presented with a subpoena by the sheriff’s department. In most cases, however, a sense of isolation and fear is created through relatively unorthodox means. The scenes in the Edgemar station seem eerie because the pace of the acting is calm and deliberate, and because the rooms look unusually empty. Here and in the courtroom, the background music is understated, and the soundtrack is cleverly mixed to create a dimly heard ambience of random, institutional, and ghostly chatter. In exterior scenes, the mise-en-scène is even more strange. Night-for-night sequences are bathed patterns of orange and blue light, and the city streets are weirdly deserted. Crimes occur in antiseptically empty spaces: clean but underpopulated strip malls, lonely gas stations, vacant warehouses, abandoned houses, and streets devoid of cars. Each time Johnson and Fields are called to investigate, they find themselves in a quiet, deserted spot, where the silence is suddenly broken by a swarm of black-and-white police cars and uniformed troopers arriving en masse. In scenes such as these, Burnett takes advantage of his low budget to create an oppressive void, a neo-Kafkaesque vision of fascist repression and racist brutality. He seems to have no particular model in mind, but on a relatively subtle level, his work has something in common with a classic social-problem picture such as Crossfire.

In contrast, Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress invites direct comparison with Chinatown and the tradition of hard-boiled private-eye literature. Like Walter Mosley’s novel, the film begins in 1948 Los Angeles, near the spot on Central Avenue where Raymond Chandler placed the opening scenes of Farewell, My Lovely. As in Chandler, the plot involves a search for a missing woman who has changed her identity, and it leads to a fairly typical disclosure of sexual perversion and political corruption. But because the action is viewed from a different social, economic, and racial perspective, familiar motifs of urban noir are either intensified or neatly reversed.

Although the film’s protagonist, Easy Rawlins (Denzel Washington), is both a private eye and something of a knight errant, his motives are far more realistic than Philip Marlowe’s, and his life is placed in much greater jeopardy. Marlowe’s skin color and social polish enable him to move with relative ease through every level of the city, whereas Rawlins faces barriers each time he steps outside his immediate community. In the course of his investigation, he narrowly escapes being beaten or killed by college kids on Santa Monica Pier; he is sadistically roughed up by the white gangsters who hired him; and he is brutally assaulted by the Los Angeles Police Department, who give him a single day to solve a murder or die. He uses every skill at his command merely to stay alive, and in attempting to solve a mystery, he defamiliarizes the entire city. As Paul Arthur observes, in this film, “the white districts and their bases of individual and institutional domination…serve as the heart of darkness.”28 The dance clubs and pool halls along Central Avenue are shadowy and sometimes violent (especially when they are invaded by whites), but they seem more accommodating than Santa Monica Pier and the Ambassador Hotel. Throughout, the white world is a dangerously alien territory at the margins of “normal” life, and poor and semirural areas that were never represented by the classic studios are given an aura of peace and dignity.

Like most noir heroes, Easy Rawlins is a loner with a “dark” past, which is represented in the film by a brief flashback to his life of crime in the prewar South and by several references to the dead bodies he saw in Europe while fighting for the United States Army. Unlike his predecessors, however, Rawlins does not suffer from guilt or quasi-existential angst. He wants nothing more than a steady job, so that he can satisfy the American dream of having a home with a bit of lawn attached. Hence the normative locale of the story is not, as in Chandler, a detective’s lonely, rented office in Hollywood, but a privately owned bungalow in working-class Watts, where we see children at play in the streets. “I guess maybe I just loved owning something,” Rawlins tells us in his offscreen narration, as we see him driving up to his mortgaged, one-bedroom house—a sunny dwelling with hardwood floors, a breakfast nook, and a pleasant front porch looking onto a patch of grass. The film’s production designer, Gary Frutkoff, has skillfully selected and decorated this house, in the process giving a new twist to the theme of male domesticity in private-eye fiction: Rawlins lives in self-sufficient, Marlowe-like isolation, but he is also a housekeeper and a benign embodiment of capitalist progress, who enjoys planting rose bushes and communing with his neighbors.

When the film opens, a downturn in the postwar economy has deprived Rawlins and other African Americans of employment. (We see some of his neighbors loading up their autos and beginning a Joad-like migration back to the South.) In a bar on Central Avenue, Rawlins is approached by a white gangster (Tom Sizemore), who offers him a large sum of money to search the black side of town for a mysterious white woman named Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals). According to the gangster, the woman has a “predilection for the company of Negros; she likes jazz and pig’s feet and dark meat, so to speak.” But when Rawlins succeeds in finding Daphne, he discovers that she is passing for white. The sister of a black gangster from Lake Charles, Louisiana, she has become involved in an interracial love affair with one of the most influential white men in Los Angeles; moreover, she is in hiding because she has proof that a leading candidate for mayor is a pedophile. Two people who know her have already been murdered by the politician’s thugs, and she and Rawlins are next in line.

FIGURE 62. Denzel Washington in Devil in a Blue Dress (1996). (Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)