In our playgroup, we've been talking about our children's bad dreams. It seems like all the kids in the group have them at one time or another. Some have them more intensely or more often than others, but they all have them. Why do children have bad dreams, and what's the best way to deal with these?

The value of sharing stories with other parents is that you learn something very reassuring: no matter what situation you're dealing with, other parents are having the same experience. As you have discovered in this case, all children have bad dreams. Dreaming is the time when the brain sorts through the day's events and emotions. Children spend substantially more time in the dreaming stage of sleep than adults do, so they have many more dreams—both good and bad. The intensity of toddler and preschooler dreams mirrors the intensity with which these little people live, so dreams can be surreal exaggerations of real life. In addition, a young child's vibrant imagination, curiosity, and creativity are evident even during sleep. In light of all these reasons, it's easy to understand why all children have bad dreams and why research shows that episodes of nightmares are at their peak during the ages from three to six.

Everyone dreams, and dreams can be good, neutral, or bad. A nightmare is a bad dream that results in a partial or full awakening. The child, coming fresh from the dream, remembers what she was dreaming about and retains the emotions of fear or anxiety that were the theme of the nightmare. So, in a sense, a nightmare actually becomes a nightmare when a child wakes up and consciously thinks about the dream she just had.

As adults, when we wake up from a dream in bed and in the dark, no matter how vivid it was we immediately identify the experience as a dream. A young child, on the other hand, hasn't quite mastered the understanding of life versus dream, reality versus fantasy, real versus pretend. When your child wakes with a nightmare, he will likely be confused. For young children, telling them, "It was just a dream" doesn't quite explain what they just experienced. They don't have the wisdom yet to understand the fantasy aspect of dreams; after all, most of them believe that the Tooth Fairy, Santa Claus, and Big Bird are real. Keeping this in mind, it only seems fair to comfort children in the same way we comfort them when they face a tangible fear or danger, since the emotions they feel are likely the same.

The following are things you can do if your child wakes with a nightmare:

• The most important thing you can do when your toddler or preschooler has a nightmare is be there and offer comfort, just as you would in any other situation when your child is feeling afraid or hurt.

• Stay with your child until she feels relaxed and ready to go to sleep. If she's reluctant to have you leave her side, go ahead and stay with her until she is actually sleeping.

• Stay calm. Your attitude will convey to your child that what's happening is normal and that all is well.

• Reassure your child that he's safe and that it's OK to go back to sleep.

By far, the easiest way to offer comfort and get your child—and yourself!—back to sleep quickly is just to scoop her up and bring her to your bed. Or if she has a toddler bed or floor mattress, lie down beside her until she (and possibly you) fall back to sleep. If this works for you, then you've found a simple solution.

Unfortunately, though, easiest is not always the right answer. The decision on this topic depends on your family's feelings about co-sleeping and where you are in your own child's sleep plan. If you're not comfortable with bringing your child to your bed, if you are in the middle of a plan to move your child from the family bed to his own bed, or if you've just recently done so, you may want to avoid bringing him back to your bed, even after a nightmare. Doing so may create a situation where your child will suddenly start having "nightmares" just as soon as she goes to bed. (Which is quite peculiar, since nightmares usually occur during the second half of the night or early morning. Just goes to show you how bright and creative your child is.)

If you choose not to bring your child to your bed, you still have plenty of other ways to offer comfort until your child is settled and ready to go back to sleep. You can sit beside him, take him to a rocking chair for a cuddle, or set him up with a snuggly blanket, some soft music, a night-light, and a favorite lovey toy to snuggle.

Let your child set the pace for discussion about nightmares. In the morning he may or may not remember what happened, and even if he remembers, he may or may not be thinking about it much. If he brings it up and does want to talk about it, let him explain what happened. Keep in mind, however, that it may be a very disjointed story. You can listen with interest, and then tell your own version of the story: give the nightmare a resolution or a happy ending. Pick out the main points, which may often involve a monster or an animal, and help your child come up with a great way to finish the story. The monster or animal might run away or become friendly. If you have an older child who seems to want to delve deeper into the topic, you can have him draw a picture of the nightmare. Then make a production about drawing a second picture that shows a resolution, or get rid of the nightmare once it's on paper—crumple it up and throw it away. This technique is often helpful in reducing future episodes of nightmares.

Night terrors are completely different from nightmares or bad dreams. These mysterious episodes are also referred to as sleep terrors, since they can occur during daytime naps as well as nighttime sleep. Any parent who has witnessed a child in the process of a night terror will understand completely why it has the name— it can be terrifying for the parent to observe. During a night terror, your child will wake suddenly, and she may let out a panicky scream or a fearful cry. Her eyes will likely be opened and her pupils dilated, but she won't be seeing. She may hyperventilate, thrash around, or talk or yell in a confused incoherent manner. She may be sweating, her face may be flushed, or her heart might be beating rapidly. She may jump out of bed or even run around the room. She'll act as if she's being chased or threatened, or she may appear to be terrified by a horrible nightmare.

Actually, your child is not frightened, not awake, and not dreaming. She's sound asleep and in a zone between two sleep cycles, somewhat stuck for a few minutes. When the sleep terror passes, she'll resume the cycle before it was interrupted. The child having a night terror is not having a nightmare, is unaware of what's happening, and won't remember the episode in the morning. So the terror part of night terrors is named not for the child but for the parent who watches the disturbing scene.

Now that you understand what night terrors are all about, it should take some of your fear and concern away. While it may still be difficult and unsettling to watch your child during an episode, you can rest assured that your child is neither awake nor frightened.

This is the hard part. A parent's natural response upon seeing the child acting terrified is to hold him and comfort him, to which he would respond by calming down. During a night terror, however, your child is not awake nor aware of your presence. You may try to hold him, but trying to hold a thrashing child during a night terror usually results in his pushing you away or fighting you off— making the whole thing even more frightening for you. In this case, you can try a gentle pat or touch along with a series of comforting words and shhh, shhh sounds, but realistically these might be more to give you a sense of doing something to help rather than achieve any real purpose.

If your child gets out of bed, you can try to lead him back. If he's sitting up, you can try to guide him to lie back down. There is no value in waking your child up; in fact, trying to wake him may just prolong the episode.

Your goals are to keep your child safe by preventing him from falling out of bed, down the stairs, or banging into furniture and to get him back to bed after the night terror has run its course.

Given that your child isn't aware of what's happening during the episode, since he most likely has no memory of it and can't control the night terrors, there's no reason to talk to him about what's happening. Actually, doing so may just upset him and cause him to worry or fear bedtime.

While you shouldn't talk to your child about the night terrors, do remember to talk to a grandparent or baby-sitter who may tend to your child during naptime or sleep time. If your child has older siblings, talk to them as well. Let them know a little about night terrors, and reassure them that what happens during a night terror is normal. Tell them exactly what might happen and how to handle the situation. Take care that little ears aren't overhearing the conversation, since your child might hear bits and pieces and make assumptions about what he hears. This could cause him to become confused or scared.

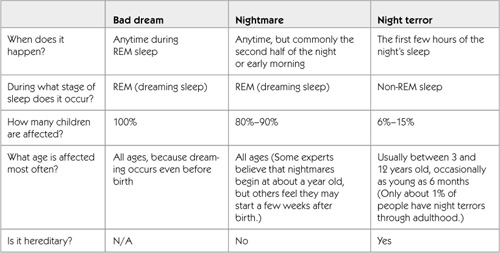

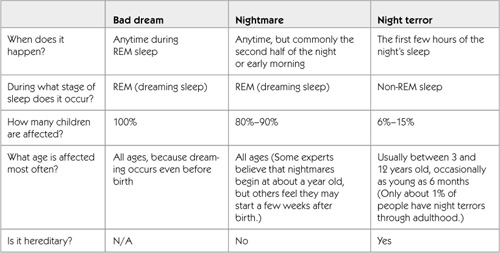

The chart on the next page is a quick reference for figuring out what's going on with your child when nighttime frights appear.

To a certain extent you can't really prevent your child from having nightmares or night terrors. However, some things have been found to reduce the number of episodes or the severity of the episodes. Even if you can't prevent these, some of the following tips will help your child learn how to deal with nightmares or the feelings of fear and uncertainty if he wakes up after a bad dream:

• Monitor the movies and television that your child watches, during the day as well as in the evening, since scary images can show up in your child's nightmares. Pay attention to not only the shows she watches but also whatever is on the screen when she's in the room. Just because it's a program created for children doesn't make it safe: many cartoons and children's shows are filled with images of violence. So choose carefully what you allow your child to watch. Keep in mind that young children can be scared by things that adults might find amusing. Watch your child's reaction, more than what's on the screen, for a true indication of his response.

• Avoid books that have pictures or stories that disturb your child. Again, watch your child for cues to her feelings, as toddlers and preschoolers can find the oddest things frightening. For example,

many toddlers are afraid of clowns, trolls, human-looking dolls, or distorted images of real things.

• A child who is overtired or sleep deprived will have more episodes of nightmares or night terrors. If your child is plagued by night problems, the first step is to check out your child's sleep hours according to the table on page 12. Then read over the tips in Part I of this book to create a consistent bedtime plan.

• An erratic sleep schedule can contribute to sleep terrors and possibly to nightmares as well. Aim to have your child in bed at the same time every night and see if this reduces these nighttime problems.

• Make sure you follow a calm and peaceful routine the hour before bedtime. This will ensure that your child falls asleep while feeling happy and safe.

• If your child is taking medication, ask a pharmacist or your health care professional whether the medication could be disturbing your child's sleep.

• Children with special needs or those with ongoing medical ailments may have more frequent or severe nightmares or night terrors. If your child has any special health conditions, discuss this possibility with your health care provider, or chat with parents of children with similar health circumstances to share ideas.

• For some children, a heavy meal before bed may bring on nightmares or night terrors. If your child currently eats a big meal before bedtime, experiment with an earlier dinnertime and provide your child with a light snack an hour or two before bedtime.

• Some children have more night terrors if they are new to nighttime dryness and go to sleep with a full bladder. Remember to have your child use the potty just before she gets into bed, even if she "just went" or "doesn't have to." Encouraging her to go potty one last time before getting into bed may help prevent night terrors. Examine your child's life situation to see if stressful conditions may be promoting nightmares. Stress from situations like the parents' divorce or marriage, a move to a new home, the birth of a new sibling, or the death of a family member or pet can manifest themselves into nightmares. If you can pinpoint a problem and find ways to reassure your child that he is safe, it may help reduce the intensity or frequency of nightmares.

• Some children find that hanging up a sign in their bedroom is reassuring. Make one that says, "Good Dreams Only" or "No Bad Dreams Allowed," and decorate it with happy pictures. Hang it in your child's room or on her door.

• Some children find comfort in hanging a dream catcher above their bed or on their window. This Native American ornament made of webbing, beads, and feathers "catches" the bad dreams and lets the good dreams flow through.

• Your child may be uncertain about whether what happens in a dream is real or imaginary. During the day you can begin teaching your child the difference between "real" and "pretend." Point out things in a movie or on television, and discuss whether they are real or not. Point out how she can "see" a picture in her head when you tell her a story and how this is sort of like a dream that happens when she's sleeping. An older child may be taught how to finish a bad dream by adding a good ending to it.

Don't ever hesitate to call a professional if you have concerns about your child's sleep. A professional can help you in a variety of ways. These include techniques that can be used to control episodes of sleep terrors or nightmares without the use of medication.

You should discuss your child's situation with your health care professional or a pediatric sleep specialist if any of the following occur:

• Your child has frequent, intense nightmares.

• Your child has night terrors three or more times per week.

• Your child is afraid to go to bed because of a fear of nightmares.

• Your child sleepwalks or runs in her sleep during episodes, putting herself in possible danger.

• You have questions that this book hasn't answered or your instincts tell you that something isn't right.

• You have tried all the tips provided here but your child is still having problems with nightmares or night terrors.