SELF-HELP: A LITERARY HISTORY

Walk into a contemporary bookstore and self-help manuals are likely to be among the first books you’ll see. In my local Barnes & Noble, a “self-improvement” section is featured in the vestibule, luring customers before they even open the store’s main doors. Inside the store, the boundary between self-help manuals and literary fiction appears curiously blurred, with Paula Cocozza’s novel How to Be Human, for example, displayed next to Heather Havrilesky’s advice compendium How to Be a Person in the World.1 Far from being particular to the era of the corporate bookstore chain, self-help’s overlap with the literary has a long and varied history marked by negotiation, strife, influence, and imitation. Novels and success manuals have been competing for readers’ attention at least since the late nineteenth century, when they vied for space on the same early best-seller lists.

Self-help and literature have historically been ambivalent shelf-fellows, but today the two industries appear to court and even encourage their mutual conflation. It can be difficult to discern from covers alone whether one is standing in the self-help section or among the new releases in fiction. The literary vanguard has taken to emulating self-help’s language and packaging in works such as Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, Mohsin Hamid’s How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, Eleanor Davis’s How to Be Happy, Terrance Hayes’s How to Be Drawn, Jesse Ball’s How to Set a Fire and Why, Ryan North’s How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler, and many more.2 Serious literature has a reputation for resisting the vulgarity of use, and popular readers are known for shunning preachy lessons. But as I reveal in this book, rather than a deterrent, the prospect of a moral lesson has historically drawn readers from all over the world to even the most obscure and impractical narratives. The desire for self-help links such diverse reading cultures as samurai in Meiji Japan, late-Victorian French hobbyists, mid-twentieth-century Nigerian taxi drivers, and Reagan-era Dear Abby devotees.

Self-help’s textual practice draws on the Renaissance tradition of the commonplace book: a scrapbook that assembled and recopied quotations for personal use and was meant to “lay up a fund of knowledge, from which we may at all times select what is useful in the several pursuits of life.”3 Book historian Robert Darnton explains how “early modern Englishmen read in fits and starts and jumped from book to book.” This Renaissance practice of reading nonsequentially for personal use offers a window onto the way that reading and writing once “belonged to a continuous effort to make sense of things.”4 Over time, and with the rise of the modern research university, this classical view of literature as life preparation was gradually supplanted by specialized models of literary study, accompanied by what philosopher Michel Foucault has described as the subordination of self-care to self-knowledge.5 However, this fragmentary and utilitarian approach to reading remains active in self-help. In her analysis of female self-help readers, Wendy Simonds discovered that “they are more likely to subvert the physical authority of the text than they would in fiction: they skip around, read halfway through and abandon the book, read only the chapters they think will pertain to them or their particular situation, or even use a book by reading the back cover and quickly skimming through it in the bookstore.”6 Such practices have found an outlet not only in self-help books but also in the “hyperlinked homilies” and “virtual verities” circulating in digital culture.7 Self-help books are now “part of an extensive web of psycho-media.”8 As Boris Kachka, a journalist who covers literature and the publishing industry, complains, “today, every section of the store (or web page) overflows with instructions, anecdotes, and homilies.”9 This overflow into every genre, section, and web page is what makes recognizing self-help as a transmedia, cross-cultural reading practice so urgent.

Self-help’s most valuable secrets are not about getting rich or winning friends but about how and why people read. All self-help, even Dale Carnegie’s 1936 How to Win Friends and Influence People, advances a textual pedagogy. “The great aim of education,” wrote Carnegie, quoting Herbert Spencer, “is not knowledge but action. And this is an action book.”10 Ever since its emergence out of Victorian working-class associations, self-help has operated as an alternative pedagogic space to the academy—one whose breezy, instrumental reading methods contrasted with the close, disinterested paradigms promoted by the modern research university. This modern university had little interest in Carnegie’s proposed course on public speaking, which contained the seeds of his best-selling manual. His course was rejected by both Columbia and NYU, leading him to settle in 1912 on the Harlem YMCA as his venue. In the introduction to How to Win Friends and Influence People, Carnegie scoffed: “Wouldn’t you suppose that every college in the land would conduct courses to develop the highest-priced ability under the sun?”11

Yet it was not just Carnegie’s subject matter but also his reading and research methods that dissuaded academic institutions from securing his talents. His practice of liberal copying and unsignaled paraphrase was at odds with the originality and propriety prized by institutional academic culture. Described by a friend as “condensation’s greatest zealot,” Carnegie’s manual repurposes the insights of thinkers from Lin Yutang to William James.12 Even in person, it seems, Carnegie had a tendency to speak “in quotations, along with the qualifying phrases, mostly from his book, which he knows by heart.”13 His approach was in keeping with self-help’s unapologetic derivativeness (in the 1883 self-improvement manual Room at the Top, author A. R. Craig humbly signs off as “The Compiler”).14 Long before theorists began announcing the “death of the author,” self-help authors had abdicated the originality claim.15 With their collating of wisdom literature from Confucius to Charles Schwab, self-help handbooks have historically supplied de facto syllabi for those excluded from elite educational institutions (indeed, many early guides included recommended reading lists as appendices). Above all, whether explicitly or implicitly, these guides modeled how to read.

In addition to Carnegie’s practical methods, his research ethics also ostracized him from scholarly circles. A controversy erupted in 1919 after Carnegie submitted an article purportedly written by one of his business students touting the transformative effects of his public speaking course, “My Triumph Over Fears That Cost Me $10,000.00 a Year,” when the journal editors of the academic Quarterly Journal of Speech Education discovered that Carnegie had fabricated the account.16 But his penchant for invention soon found another, more literary outlet. In 1922, in the modernist pattern of Hemingway and Stein, Carnegie moved to France to pen his own Lost Generation epic, explaining that “in my early thirties, I decided to spend my life writing novels. I was going to be a second Frank Norris or Jack London or Thomas Hardy.”17 During the same period that James Joyce was in Trieste trying to re-create the Dublin of his youth, Carnegie journeyed to the French countryside to reconstruct his native Maryville, Missouri: “I am going to put that fountain with the gold fish back in Schumacher and Kirch’s grocery, and the hitch racks back around the court house.”18 The novel, originally titled The Blizzard and later retitled All That I Have, participated in the same ironic portraits of pious, small town life that defined the modernist satires of Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis.19

When publishers rejected his novel, describing it as “worthless,” Carnegie suffered a serious blow.20 The rejection led to a crisis of self-reassessment and hastened his 1926 return to the United States, this time under his revised name (from Carnagey to Carnegie, after the entrepreneur-philanthropist), to resume his public education initiatives.21 Although Carnegie came to accept that his talents lay elsewhere than in literature, he retained his admiration for the craft and power of the written word. “Genius is the creation of a cliché,”22 wrote Charles Baudelaire, and Carnegie concurred, remarking that it is “easier to make a million dollars than to put a phrase into the English language.”23

Dale Carnegie writing his novel in the European countryside.

Credit: Courtesy of the Dale Carnegie Estate.

That “How to Win Friends and Influence People” has become a stock phrase, leading to parodies such as Lenny Bruce’s How to Talk Dirty and Influence People and Toby Young’s How to Lose Friends and Alienate People, suggests that Carnegie eventually attained his ambition.24 But in a classic example of self-help’s penchant for repurposing, the phrase has a longer history. Already in 1902 the expatriated Canadian hustler Victor Segno, who opened the “Segno School of Success” in Los Angeles, had used a variation of the saying in a chapter titled “How to Win Friends and Affections” from his handbook The Law of Mentalism, which contains passages that anticipate those found in Carnegie’s book. Segno writes, “if one should desire to win the affection of some particular person, I would advise him to proceed systematically to gain that desire … and if his thoughts are backed by sincerity, they will be accepted…. If he is insincere, he cannot hold the affection.”25 Segno’s caveat was echoed in Carnegie’s insistence that, contrary to appearances, he is not advocating flattery but rather “honest, sincere appreciation.” “No! No! No! I am not suggesting flattery! Far from it. I’m talking about a new way of life. Let me repeat. I am talking about a new way of life.”26 Like so much of self-help, Carnegie’s quintessential slogan of American success possesses buried international origins—it may well have been inspired by an expatriated Canuck.

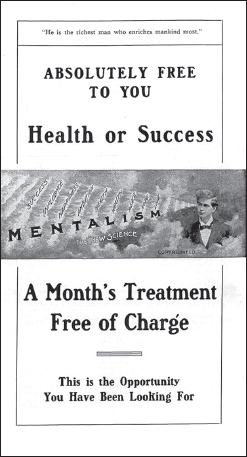

Promotional pamphlet for Victor Segno’s Mentalism (Los Angeles: Inspiration Point, Echo Park, 1911).

Though self-help appears to endorse the trope of self-making, the industry is defined by brazen textual recycling. More than a sheer manifestation of self-help’s ruthlessly appropriative capitalist energies, this tendency offers a glimpse into its surprisingly collaborative textual ethos. Self-help’s citation practices manifest our cultural interdependence in a manner analogous to how, according to Bruce Robbins, “reading upward mobility stories may be deviously teaching us not to be self-reliant and self-interested, as is usually taken for granted. It may be teaching us to think about the common good.”27 At its best, self-help is an extension of the advice tradition’s commitment to a communal archive of human experience.

The self-improvement industry has been analyzed in a variety of academic disciplines, but its literary import has not received the attention it demands.28 The omission is even more glaring in light of the fact that self-help guides are among the most lucrative book genres of the past thirty years, with approximately 150 new self-help titles published every week.29 Uniting the majority of economic, historical, and sociological scholarship on self-help is the view that the industry is fueled largely by fear, anxiety, and insecurity. Although the literary angle does not disprove the influence of these motives, one of its most striking revelations concerns the affirmative impulses that compel self-help’s readership. At a time when the value of literature is often called into question, self-help offers a reminder of the promises of transformation, agency, culture, and wisdom that draw readers to books.

Though reading for improvement has fallen into disfavor among academics, self-help provides a medium through which individuals can pursue self-betterment unfettered. This is, at least, one hypothesis of how the self-help compulsion came to flourish. In declining to endorse improvement as an end of reading, the professionalization of literary study, taking its cue from high-literary celebrations of impersonality and autonomy, may have inadvertently ceded an entire market to self-help.

There are other explanations, of course. Economists stress how late-nineteenth-century class mobility created new anxieties over self-presentation among the aspirational middle classes. Sociologists and scholars of religion outline the way the anomie of industrial modernity—urbanization, secularization, the division of labor—created a vacuum that self-help strove to fill.30 Historians discuss these and others factors as part of “the turmoil of the turn of the century,” which led to rise of the “therapeutic ethos.”31 But this book is about literature and, while I draw on these hypotheses throughout, I argue that the literary perspective offers crucial insight into the ongoing appeal and evolution of modern advice. The literary paradigm points to the emergence of self-help as a defense of a specific mode of reading—for agency, use, well-being, and self-change—that was being expelled from institutional spheres.

Scholars today are wringing their hands over the question of the nature of literature’s influence and necessity. Self-help has no such qualms about its utility and insists on the singular appeal of literature to offer models for how to survive. Counterintuitive though it may seem to some, today it is possible to find a stronger defense of the charisma, singularity, and even autonomy of the literary in self-help than in most literary criticism. As Timothy Aubry puts it in Reading as Therapy, “scholars have challenged this special status [of the literary] by disputing the notion of the author as an individual genius, by treating novels and poems as if they were no different from other kinds of texts, and by analyzing them to uncover the ideological and economic forces responsible for their production. But readers outside of the academy have not surrendered their piety.”32 Likewise, Leah Price discovered in her interviews with the new breed of bibliotherapists, or what she wryly terms “biblio-baristas,” that these professionals see their mission as “wresting literature out of the hands of the killjoys who make a living chaperoning booklovers’ natural urges.”33 And so, rather than blithely negating the aesthetic, as some might assume, self-help has become an unlikely, vestigial sphere of literary veneration, however polemical or anti-intellectual its version of the literary may be.

AN ANCIENT PRACTICE, A MODERN INDUSTRY

This book employs a twofold understanding of self-help: on the one hand, as a historically specific cultural industry that emerged in the late nineteenth century out of all the historical factors I will address and, on the other hand, as a reading compulsion or hermeneutic that can be applied to any text from any time period. The self-help hermeneutic consists of strategically mining, collating, and adapting the textual counsel of the past for the purposes of self-transformation. While this practice finds a commercial apex in the American self-help manual, it transcends culture and genre and can be applied to the Bhagavad Gita or Swann’s Way.

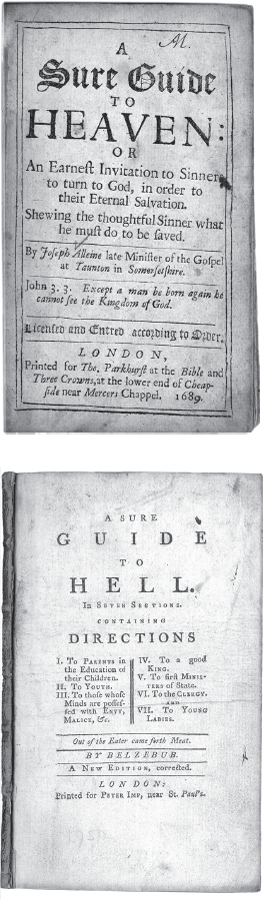

Although the turn of the twentieth century ushered in the rise of self-help as a full-fledged commercial genre and industry, there is no denying that the advice tradition has a much longer history. What is Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy if not bibliotherapy avant la lettre, Ovid’s Ars Amatoria but an ancient Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, and Epictetus’s Enchiridion if not cognitive behavioral therapy before its time?34 Some trace the Western self-help tradition back to Cicero’s De Officiis, but the golden age of advice is typically associated with the dissolution of the medieval church in the Renaissance, the period that saw the rise of parenting manuals such as Elizabeth Joceline’s The Mothers Legacie to Her Unborn Child (1622) and Sir Walter Raleigh’s Instructions to His Sonne and to Posteritie (1632), but also, as Rudolphe Bell has shown, the emergence of more contemporary-sounding guides such as sex manuals for middlebrow Renaissance Italians.35 Most agree that the prescriptive writings of the Puritans, embodied by Cotton Mather’s Bonifacius: Essays to Do Good (1710), laid the crucial groundwork for future, more secular advice.36 Already in the eighteenth century such manuals inspired parodic ripostes: Joseph Alleine’s 1689 A Sure Guide to Heaven was countered in 1751 by A Sure Guide to Hell, written by the devil himself.37 As the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries progressed, the prescriptive rules of the New England settlers were translated into conduct or etiquette guides on matters such as household management, courtship, and parenthood (a prolific author of these was William A. Alcott, Louisa May’s second cousin). Typically written for women and youth, these works vied with fictional novels for moral authority over readers.38

Early conduct guides: (top) Joseph Alleine, A Sure Guide to Heaven , 1689; (bottom) Belzebub, A Sure Guide to Hell , 1751.

Credit: Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Cardiff University.

Self-help’s seemingly indissoluble association with American nationalism is largely due to the influence of Benjamin Franklin, widely viewed as the grandfather of the field. Indeed, it will come as a surprise to precisely no one that Franklin created one of the earliest prototypes of the Western self-help manual. But this is not his Poor Richard’s Almanack, the folksy hodgepodge of proverbs, jokes, and recipes typically cited as the genre’s progenitor. Rather, it is in a passing mention in Franklin’s Autobiography (1791) that one of the first American self-help manuals proper makes its appearance, where it is described, with just a touch of regret, as a mere might-have-been. After taking a short hiatus from his Autobiography to help found the United States of America, Franklin divulges his “scheme” to write a manual that, although “not wholly without religion,” would not bear the marks of any particular sect. Although he claims to have jotted down a few ideas for the volume, Franklin demurely relates that some matters of private and public business have “occasioned my postponing it; for, it being connected in my mind with a great and extensive project, that required the whole man to execute … it has hitherto remain’d unfinish’d.” As it could not be done today, Franklin’s manual had to be put off until tomorrow, and the “great and extensive project” of self-help was introduced to America in the form of the conditional perfect—the wistful grammatical tense used for failed and aborted initiatives. “I should have called my book THE ART OF VIRTUE,” he recounted,

because it would have shown … that it was, therefore, every one’s interest to be virtuous who wish’d to be happy even in this world; and I should, from this circumstance (there being always in the world a number of rich merchants, nobility, states, and princes, who have need of honest instruments for the management of their affairs, and such being so rare), have endeavored to convince young persons that no qualities were so likely to make a poor man’s fortune as those of probity and integrity.39

Franklin’s précis strikingly anticipates the premise of Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, with its argument for the professional and economic benefits of earnest appreciation.40 In addition, Franklin’s unwritten manual provides a fitting keyhole into self-help’s overlooked embroilment in speculation, imagination, the fantastical, and counterfactual: all those qualities more commonly associated with literature than with life-management guides.

Franklin’s writings exemplify the way that the automatic association of self-help with rugged American individualism has obscured the industry’s international prehistory. After acquiring a copy of the Latin work Confucius Sinarum Philosophus from his bibliophile friend John Logan in 1738, Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette published a series called “From the Morals of Confucius.”41 It is these Confucius extracts, which reference “The Art of Being Virtuous,” that sparked Franklin’s idea for his unrealized self-help book, “The Art of Virtue.” Confucius explains, “whatever is honest and advantageous, is amiable; and we are obliged to love Virtue, because it includes both these Qualities.”42 Franklin’s borrowing from the sage reflected his admiration for the “industriousness of the Chinese” and his advice to his compatriots to emulate Chinese “arts of living.”43

Through such examples, the chapters to follow complicate the engrained view that, as Steven Starker puts it, “American individualism … is the wellspring from which nearly all self-help materials flow” or that “the ambition to succeed,” as Irving Wyllie has it, “is emphatically an American ambition.”44 As sociologist Eric Hendriks laments, “almost all research [into self-help] focuses on the US.”45 Rather than a unidirectional tool of Western imperialism, self-help emerges in this book as a crucial vector of cross-cultural exchange.

Once Franklin reluctantly put aside his manual, it took another full century for the self-help genre to gain steam. Its emergence was announced by the publication of the 1859 Victorian handbook Self-Help: With Illustrations of Character, Conduct, and Perseverance by the Scotsman Samuel Smiles, who is often credited with establishing the term, although the idea of self-culture was percolating in other, lesser-known working-class improvement treatises of the day. Smiles was forced to partially self-finance his book when it was rejected by publishers, but it quickly became a colossal bestseller all over the world. In a fascinating kind of full circle, given the lineage from Confucius to Franklin to Smiles, it is reported that in 1871 Japanese samurai, who embraced the Confucian ideals, camped overnight to buy a copy of Smiles’s Self-Help.46

Contrary to self-help’s association with the uniquely American temperament, as Samuel Smiles exhorted, “the spirit of self-help, as exhibited in the energetic action of individuals, has in all times been a marked feature in the English character.”47 Some might be surprised to learn that the term self-help was popularized in the United Kingdom in guides to working-class radicalism such as G. J. Holyoake’s Self-Help by the People (1857) and Timothy Claxton’s Hints to Mechanics on Self-Education and Mutual Instruction (1833).48 Although the phrase self-help had earlier appeared in Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle (1834) and, in variant form, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance” (1841), it found an emissary in Smiles, whose 1859 Self-Help offered unprecedented proof of the market for practical advice.49

Due in part to the way it constellates vast networks of cross-cultural exchange, Smiles’s Self-Help marks the beginning point of my inquiry. Espousing the Victorian tenets of industriousness, perseverance, honesty, and self-discipline, the book became an international sensation and an antecedent of the contemporary self-improvement guide. The manual discouraged working-class men from relying on institutions to secure their happiness and well-being, an argument that has contributed to its reputation as a handbook of laissez-faire liberalism, although its original politics were more radical. Smiles insisted that the self-help spirit could be found not only in the lives of famous generals, renowned authors, and celebrated inventors but also in the masses of common engineers, artisans, and day-laborers: “our progress has also been owing to multitudes of smaller and less known men.”50

Smiles is also a logical starting point because it is in the period between the first oratorical iterations of his self-help philosophy in 1840 and his manual’s eventual 1859 publication that self-help begins to assume the individualized form we know today. During these years, “what had been originally a working-class device to try to grasp some of those cultural and material benefits which were denied to them in the new industrial society, now became the middle-class reply to workers’ demands for better social conditions.”51 At the same time, as I maintain in chapter 1, the particular realities of self-help’s international reception do not always reinforce the genre’s ideological mission.

It was only in the wake of the success of Smiles’s work that self-help emerged as a formidable commercial industry—and the literary community, being in the book business, took notice. During this period, self-help authors looked upon literary entertainment with suspicion. With links to the asceticism of New England Puritanism, early self-help authors were wary of the diversion of novels, preferring to recommend biography and history. Although Victorian handbooks like Smiles’s Self-Help were tapestries of literary anecdote and quotation, they repudiated fiction reading as a nefarious diversion. Smiles probably did more to disseminate the Western literary canon than any other author of his time, yet he also cautioned that novels could leave readers “perverted or benumbed.”52

Fellow pedagogue William Robinson, who wrote the early handbook Self-Education in 1845, likewise warned readers “against contracting a taste for novel reading.” He conceded that “some few novels or tales are worth pursuing; about one perhaps, in two hundred; but the chance is, whether you may happen to have that individual one thrown in your way.” Due to these unlikely odds, he decided, “it will be better for you, in every respect, neither to taste, nor to handle such books.”53 In addition to its recommendations, the matter-of-fact style and tone of the self-help manual defined itself against the romance and the pomposity of fiction. In the preface to How to Make a Living (1875), George Eggleston proudly avers, in a typical proclamation, that “this little manual makes no literary pretensions whatever.”54

With the arrival of the twentieth century, the growing antipathy between literature and self-help is evident in the new vehemence with which the slogan “art for art’s sake” suddenly began to be brandished under the mantle of modernist autonomy, in part as a reaction to the perceived instrumentalism of the increasingly popular self-improvement handbook. But the rising cultural prominence of self-help also comes across in the use of the instructional, imperative mode by early twentieth-century novelists and poets as a literary gimmick. How many aspiring authors have purchased a copy of Gertrude’s Stein’s How to Write (1931) only to be discomfited by the book’s gleeful, almost mocking, inutility? Autodidacts expecting a straightforward primer in Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading (1934) have no doubt met with similar degrees of perplexity. Never mind those earnest “common readers” who picked up Virginia Woolf’s essay, “How Should One Read a Book?” (1925), only to then be chastised: “the only advice, indeed, that one person need give another about reading is to take no advice.”55

Despite its robust prehistory in the early decades of the twentieth century, most assume self-help to be a mid- to late-century phenomenon.56 This restricted understanding of self-help’s provenance has led to an impoverished sense of the industry’s reach and complexity. For instance, the narrow focus on self-help’s late-century apex has obscured the cross-cultural exchange that was integral to the industry’s development, from charismatic personalities such as Émile Coué and George Gurdjieff to the Eastern philosophy found in American handbooks such as Wallace Wattles’s The Science of Getting Rich (1910), inspired by Hindu philosophy,57 and Horace Fletcher’s Menticulture (1897), which refers to Japanese culture as “a missionary of the art of true living.”58 (Fletcher also invented a faddish system of mastication, Fletcherism, that Henry James claimed, in a letter from March 15, 1910, “bedevilled my digestion to within an inch of its life.”59) As my case studies make plain, self-help was already a major international print market in the first decades of the twentieth century, well before How to Win Friends and Influence People came along.

Rather than offering an exhaustive inventory of every instance of historical overlap between literature and self-help, I burrow into the moment of their most violent and radical opposition in the first decades of the twentieth century. It was during the early twentieth century that self-help began to more fully resemble the industry we know today; that is, it went from being a gamble in the nineteenth-century print market to a commercial juggernaut. A convergence of factors enabled the industry’s coalescence at that time: the commercialization of the self-culture of the late Victorian era,60 the rise of mass literacy spurred by nineteenth-century education legislation, the proliferation of semioccult mail-order schemes in which many self-help pamphlets originated, and, above all, the rise of the proto–New Age movement of New Thought, which marked the early twentieth century as a watershed moment for self-help.

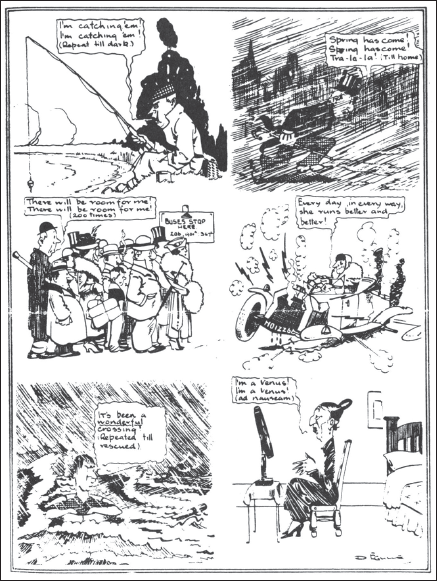

A mind-healing movement that flourished between 1875 and 1920, New Thought argued for the universal divinity and spiritual power of all thought. It combined strains of Transcendentalism, Swedenborgism, Christianity, and Hindu philosophy to promote the individual’s power to achieve health and prosperity through affirmative visualization. In the 1920s, books on what French New Thought pioneer Émile Coué called “autosuggestion” outsold those on psychoanalysis. Originally a chemist, Coué took a mail-order course in hypnotism, began seeing patients in his pharmacy and home, and eventually renounced hypnotism in favor of “suggestion,” which, unlike hypnotism, could be self-induced. His teachings became known as the “New Nancy School” and attracted disciples such as Roger Fry, Katherine Mansfield, and Italo Svevo. Coué’s book Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion instructed readers to repeat the affirmation “Tous les jours, à tout point de vue, je vais de mieux en mieux” [Every day, in every way, I’m getting better and better] twenty times in the morning and at night. It must be uttered with conviction, Coué instructed, and with the aid of a string with twenty knots to keep count, just as on a rosary.61 During this time, some people, such as the editors of The Saturday Review, saw Couéism as “a refreshing antidote to the heavy overdose of fashionable Freudianism from which the semi-intelligent are at present suffering.”62 New Thought’s immediacy and optimism made it a more palatable alternative to Freud’s dark and unsettling theories of human sexuality and desire. New Thought appeared to liberate readers from dependence on scientific authorities while also reassuring them that their unconscious desires could be funneled toward productive, even lucrative, ends.

Émile Coué cartoon, The Bystander, April 19, 1922.

Although self-help was no doubt abetted by the vulgarization of theories of the will and the unconscious taking place through American translations and adaptations of Freud, the first of which, by A. A. Brill, appeared in 1909, psychoanalysis, like high literature, distinguished itself from such therapies in its abstention from dispensing advice: “You are misinformed if you assume that advice and guidance in the affairs of life is an integral part of the analytic influence,” Freud wrote. “On the contrary, we reject this role of mentor as far as possible … we require [the patient] to postpone all vital resolutions such as choice of a career, marriage, or divorce, until the close of the treatment.”63

In light of their opposing methods, it is ironic that so many of the key concepts of psychoanalysis—for instance, the discourses of childhood trauma, self-destructive behavior, and wishful thinking—came to be absorbed and reanimated as clichés of self-help culture.64 Though intellectuals tend to emphasize Freud’s influence on modern conceptions of the self, with its infiltration of economic, corporate, advertising, and popular discourse, we have inherited New Thought’s world. As professor of history Maury Klein comments, “within a remarkably short time the New Era [of the late 1920s American economy] became the application [of Coué’s slogan] on a colossal scale long after Coué had been forgotten.”65

Early twentieth-century bookstores did not yet house self-help or personal growth sections, an important aspect of the industry’s complex and belated bibliographic self-identification, but they could have included such sections, which would have been well stocked with titles such as How to Be Happy Though Married; The Scientific Elimination of Failure; Eat and Grow Thin; Are You You?; How to Analyze People on Sight; How to Live Life and Love It; The Conquest of Worry; It Works; What the Hell Are You Living For?; The Art of Thinking; Life Begins at Forty; and far too many others to list.66 These titles often appeared as installments of pocket philosophies such as Putnam’s “handy books” and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s Little Blue Books.67

As early as 1864, Charles Baudelaire’s prose poem “Assommons les Pauvres” [Let Us Flay the Poor] reflected on the popularity of these early guides:

For a fortnight I was confined to my room, and I surrounded myself with the books of the day (sixteen or seventeen years ago); I mean those volumes which treat of the art of making people wise, happy, and rich, in twenty four hours…. I was in a state of mind bordering on intoxication or stupidity….

And I went out with a great thirst. For a passionate taste for bad reading engenders a proportional need for fresh air and refreshments.68

Baudelaire’s poetry here emerges precisely as the “fresh air” to self-help’s stale nostrums, a point reinforced by Edith Wharton, Henry James, Gustave Flaubert, Flann O’Brien, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, and Nathanael West, who, as we shall see, defined their styles partly in recoil against self-help’s instrumental materialism.

If self-help, like popular reading in general, was once premised on “a refusal of the refusal” of the aesthete, to quote sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, the aesthete’s refusal has a whole new kind of cultural purchase now that the discourse of affirmation has been utterly co-opted and degraded.69 It is because authors such as Proust, Kafka, Joyce, and Woolf refused to supply readers with the easy solutions the self-industry thought that they wanted (whether readers really wanted such facile answers is a question I address in later chapters) that modernism is now experiencing a revival as a source of useful countercounsel in our advice-saturated culture.

In recent self-help works, modernism has become an unlikely mascot for the embrace of resilience in the place of perfectionism, realism rather than “cruel optimism.”70 With their appeals to the most impractical of literary genres for advice, such guides strangely enact Marjorie Garber’s contention that “the very uselessness of literature is its most profound and valuable attribute.”71 Alain de Botton’s How Proust Can Change Your Life may be the most successful self-help reading of modernism to date, but it is far from an isolated phenomenon. In the past decade, countless self-help readings of modernism have emerged—A Guide to Better Living Through the Work and Wisdom of Virginia Woolf; Why You Should Read Kafka Before You Waste Your Life; Ulysses and Us; The Heming Way; What W. H. Auden Can Do for You; and What Would Virginia Woolf Do?72 Together, these guides unwittingly disclose a history of generic reciprocity that literary criticism has largely overlooked.

Given our endless subjection to a barrage of unsolicited advice, the most reliable guides today appear to be the most reluctant ones. In The 4-hour Workweek, Timothy Ferriss turns Samuel Beckett’s “fail better” quotation into an entrepreneurial catchphrase,73 and in The Last Self-Help Book You’ll Ever Need, Paul Persall coins the phrase “The Tono-Bungay Effect,” from H. G. Wells’s 1909 parody of quick-fix culture, to urge readers to resist overly credulous, compliant thinking.74 Svend Brinkmann’s recent life-management guide extolls works that “lack illusions and focus on negative aspects.” In particular, those difficult authors writing at the turn of the twentieth century now appear prescient for the way they expose the bad faith of the culture industry and “remind you how little control you have over your life, and also show you how it is inextricably entangled with social, cultural, and historical forces.”75

Due to its resistance to Victorian moralism and its celebration of aesthetic autonomy, literary modernism is a canvas that brings the brushstrokes of self-help’s utilitarian flourish into stark relief. Such difficult literature makes the compulsiveness of self-help to which my title refers particularly dramatic and visible. “Compulsion” is not meant to preclude the potentially generative or productive aspects of self-help reading, but refers to its undeterrable quality, its self-perpetuating persistence. Self-help reading participates in the way that “hyperbolic forms of control can bespeak their polar opposite, a deep anxiety about the chaos that seems to threaten,” as Jennifer Fleissner describes compulsion.76 Of course, modernism is neither the sole nor the most privileged object of self-help’s compulsive attentions. Self-help readings of Shakespeare, Montaigne, and Jane Austen abound,77 but the turn to modernism for advice is unique in the way that it undermines the authors’ own vehemently antiutilitarian agendas. The deterrent complexity of avant-garde narrative forces readers to articulate, even reconsider, the expectations they bring to literary texts.

There is no denying that self-help appropriations of modernist insight, such as Ferriss’s Beckett catchphrase, can easily be read as another depressing example of the way all gestures of negation and refusal are fated to be co-opted by the culture industry. It is with a grim irony indeed, as Raymond Williams observes, that “the painfully acquired techniques of significant disconnection are relocated” and “the isolated, estranged images of alienation and loss, the narrative discontinuities, have become the easy iconography of the commercials.”78 Self-help’s preoccupation with modernism is symptomatic of the surplus desires that are not being met by commercial and conventional self-improvement discourse. These guides point to modernism’s continued status as an irritation in self-help culture—and are a reminder of that culture’s limits.

The rising status of literature in self-help also reflects the growing embrace of specialized knowledge in the commercial field, with guidebooks appealing to experts in science, sociology, economics, and medicine to substantiate their counsel. Authors like Carnegie drew upon the hard-earned insights of intellectuals for inspiration and corroboration, but since his time the kind of knowledge self-help is invoking has only grown more technical and precise.79 Instead of simply being set in opposition to useful generalization, the esoterica of a discipline or métier offer a resource of technical knowledge that self-help authors can translate for readers into pragmatic lessons. (This is what journalist Dwight Macdonald called the “alchemy in reverse” of popularizing abstruse works.80) As specialists in the most extreme and seemingly hermetic aspects of aesthetic experimentation, modernists take their place among the neurobiologists and social scientists as possessing arcane and therefore valuable knowledge about their particular literary office. Those very modernist tendencies that once made serious literature appear so elitist and remote—its hermetic linguistic experiments, disdain for mass satisfactions, and wariness of popular taste—are now its saving remnant: the key to its continued value and relevance. This is not despite but because of the fact that it is with literary modernism that the schism between commodity and aesthetic culture appears more unbridgeable than ever before. However, much like the New Critics and the poststructuralists who followed them, the modernists did not entirely eschew practical wisdom but developed a recursive, dialogic style of counteradvice.

Of course, the rise of self-help is inextricable from the issue of social class. Joan Rubin has suggested that late-Victorian self-culture invented the middlebrow as such, and this is even more specifically true of self-help.81 Self-help played a significant but under-acknowledged role in the two key middlebrow polemics of the twentieth century: the first by Woolf in her 1932 piece on the “Middlebrow,” a subset that for her was personified by her longtime adversary Arnold Bennett, who had offended her not only with his cutting reviews of her novels but also with the crudity of his practical “pocket philosophies,” titles such as How to Live on Twenty Four Hours a Day and Literary Taste: How to Obtain It. As Woolf scoffs, “how dare the middlebrows teach you how to read—Shakespeare for instance? All you have to do is to read him.”82 The second middlebrow polemic for which self-help offered crucial subtext was instigated by New Yorker journalist Dwight Macdonald, who famously coined the pejorative “midcult.” What links all of Macdonald’s influential invectives against popular taste is his abiding disdain for self-help: from his 1952 contempt for Mortimer Adler’s “Cashing in on Culture,” to his 1954 takedown of the plague of “Howto” books invading America, to his 1960 “Masscult and Midcult” essay, which cites Norman Vincent Peale and Ella Wheeler Wilcox as examples of the midcult’s “tepid ooze.”83

As Macdonald’s exasperation with the proliferating how-to guides suggests, the paperback revolution in publishing was another important factor contributing to self-help’s ascent. How to Win Friends was an early test case of the controversial question of whether paperbacks would destroy demand for hardcovers of the same work, as some publishers feared (they did not). As a result of the success of Robert de Graff’s pocket editions of Carnegie’s books, publishers began developing lines of inexpensive fiction and nonfiction paperback books. Sales of pocket books rose from three million in 1939 to two hundred million in 1950.84

Macdonald’s complaints also reflected the way that the growth of 1950s consumer culture and of that “other directedness” necessary for corporate success had abetted self-help’s spread.85 In his tirade against the “howto” mania sweeping American society during these years, Macdonald laments that “everything that was once a matter for meditation and retreat into the wilderness has been reduced to a matter of technique.” He surmises that “as world issues appear increasingly hopeless of solution, people console themselves with efforts in spheres where solutions are more manageable—the practical and the personal.”86

Although the ideas of self-help and the middlebrow used to be inextricable, as Macdonald’s polemic and Aubry’s Reading as Therapy elucidate,87 it is increasingly the case that the omnivorous readers who peruse The New Yorker belong to the same educational strata as those who enjoy Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love88 or who seek therapeutic counsel from advice columnist Cheryl Strayed. Therapeutic culture offers a broader context for situating the intellectual tendency to “excoriate rather than to analyze” that has informed the reception of self-help. Both self-help and the therapeutic are thought to exacerbate the feelings of personal insufficiency and dissatisfaction upon which consumer capitalism feeds.89 Nevertheless, this book is less concerned with self-help as a form of therapy than with self-help as an alternate pedagogy. Put differently, I am less interested in self-help’s therapeutic agenda than in the cultural and literary labor the industry implicitly performs.

The growth of the “creative economy” in the latter half of the twentieth century has co-opted the jargon of well-being, self-optimization, and self-actualization for the liberal-managerial class.89 Today the middlebrow stigma of self-help has been largely supplanted by corporate absorption of the wellness industry and the integration of self-care into Silicon Valley start-up culture. No longer just a pastime of the middlebrow, today we are witness to a new wave of “highbrow self-help.”90 These are “self-help books for the rest of us”91 or, as one guidebook bluntly puts it, “life advice that doesn’t suck.”92

TRAVERSING THE JOKE

As these opening pages have outlined, self-help has a history of promoting itself as an antidote to intellectual bombast and aesthetic idealism. Conversely, serious literature has long defined itself against the instrumental pedantry of popular advice. But behind this polemical opposition, a relation of mutual intrigue and influence was also developing. The fluidity between the literature and self-help spheres is already discernable in the paratextual materials that bookended early self-help guides. Publishing houses like Henry A. Sumner & Company, which sold A. Craig’s Room at the Top, Or How to Reach Success, Happiness, Fame, and Fortune (1883) as well as popular works of fiction, would use the same terms to promote their forthcoming novels in the endpapers as were sprinkled throughout the preceding self-help guides. For example, the novel No Gentleman is “The Success of the Year,” while another title, Her Bright Future, was marketed to pique the success-hungry reader’s interest.93 Some novels would borrow from advice literature’s instructional appeal, as in Peter Kyne’s 1921 fictional The Go-Getter: A Story That Tells You How to Be One.94 In other cases, as with James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), as I elucidate in chapter 4, or, later, Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique, a book would be disingenuously marketed as self-help even though this designation strayed from the text’s real purpose or intention.95 Conversely, the nebulousness of self-help, according to Viv Groskop, has enabled it to infiltrate best-seller lists under a variety of labels, a phenomenon Shinker has dubbed “self-help masquerading as ‘big idea’ books’ ”: “Under the guise of modern philosophy and psychology, the self-help market has taken over the bestseller lists … These books are not overtly marketed as self-help, but on the sly that is what they are: they are manuals on how to live your life, and how not to.”96 In this respect, the self-help compulsion is partly an invention of the publishing industry, which encourages visual and conceptual continuity between distinct fields in their advertising materials and marketing tactics. The blurring is further intensified by internet platforms such as Amazon, in which “one and the same delivery system directs readers to Mrs. Dalloway as a canonical novel or as [an] arch-literary self-help book.”97

These marketing strategies have methodological consequences, implying that the reading methods and expectations appropriate to the self-help guide can carry through to and find fulfillment in literature as well. This discursive overlap continues in the numerous how-to fictions emerging today (see chapter 6). As Mohsin’s Hamid’s narrator contends in How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, “all books, each and every book ever written, could be said to be offered to the reader as a form of self-help.”98 This is a sentiment with which the rising profession of bibliotherapist would vehemently agree.

In recent years, the field of “shelf-help” or “bibliotherapy” has exploded, spurred partly by the efforts of Alain de Botton, who opened his School of Life, an adult education center for London professionals, right next door to University College London. The School of Life produces its own publishing imprint, a series of “Toolkits for Life” on subjects from “How to Find Love” to “How to Be Bored.” Another offshoot of the school is Ella Berthoud and Susan Elderkin’s The Novel Cure, “an apothecary of literary solutions” that mines novels for advice on ailments from a stubbed toe to a midlife crisis.99 Publishers have quickly jumped aboard the trend: Penguin Life is a new imprint marketing “authors who share a passion for living well,” the UK’s Yellow Kite Press has devoted itself to “books that help you live a good life,” and even university publishers such as Princeton University Press are repackaging “Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers,” rebranding Cicero and Seneca in manuals such as How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management.100 Leah Price’s recent work surveys the growth of government-funded initiatives such as NHS Wales’s Books Prescription program, as well as private bibliotherapy clinics catering to the “worried well off” in what she describes as “an upmarket alternative to what librarians have long done for free.”101

The landscape has radically changed since handbooks like Smiles’s and Robinson’s warned against the effects of novel reading. In a striking about-face, contemporary self-help guides are commanding readers to put aside their how-to manuals and reach for fiction instead. “Read a novel—not a self-help manual or biography,” advises Svend Brinkmann in his popular antiguide Stand Firm. “Unlike self-help books and most autobiographies,” he notes, “novels present life more faithfully—as complex, random, chaotic and multifaceted.”102 This shift from the self-help industry’s repudiation of novel reading to its celebration of literature’s singular utility will form part of the story of the chapters that follow.

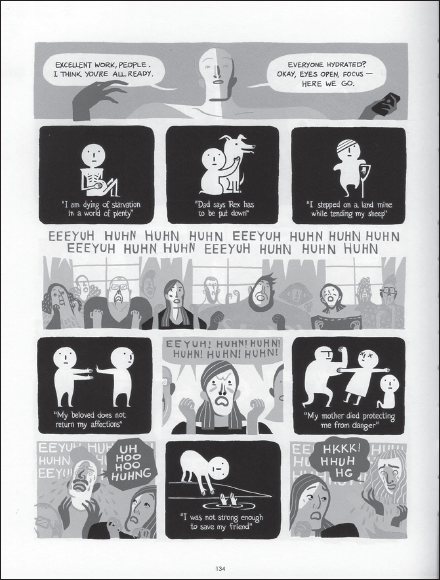

Just as contemporary self-help is becoming more interested in the practical uses of even the most rarefied fiction, novelists are growing increasingly attuned to self-help’s literary potential. Where once Flaubert, Wharton, James, and Woolf looked suspiciously upon self-help’s instrumental precepts, today the two fields are entertaining a cautious collaboration, as Hamid’s comment indicates. A good example of this more complicated, generative literary engagement with self-help is found in Eleanor Davis’s 2014 How to Be Happy, a graphic novel composed of vignettes that interrogate the different coping mechanisms to which modern individuals seek recourse, from self-help seminars to Prozac and biological reproduction. While the comic’s serial form visualizes the repetitiousness of the self-help compulsion, its embrace of ambiguity and inconclusiveness stand in stark contrast to the self-help solutions it thematically depicts. Tightly enclosed panels juxtaposed with sprawling page bleeds dramatize the homology between life management and narrative containment.

One particular episode from the book makes this relationship explicit. In it, a character is attending a seminar led by a self-help guru for people who are unable to cry called “No Tears, No Sorrow.” Attendees of the seminar are encouraged to practice crying because “without sorrow there is no joy.”103 To help them overcome their crying blockages, they are shown tragic slides of starving children, grieving family members, and dying pets. The monochrome moralism of these cartoons couldn’t be further from Davis’s colorful, uncontainable, and ambiguous aesthetic. In using these images to launch a metareferential commentary on the manipulative use of simplistic images in the service of ideological persuasion, Davis’s comics, like most of the how-to fictions I discuss, initially appear to define themselves via their embrace of everything self-help is not.

Page from Eleanor Davis, “No Tears, No Sorrow,” in How to Be Happy (Seattle, Wash.: Fantagraphics, 2014), 134.

However, there are also affinities between Davis’s narrative methods and those of the self-help program. Loose hand sketches interspersed throughout her book incorporate motivational and therapeutic messages. Episodes depict with sympathy characters’ quests for improvement, purity, security, community, and validation. Davis addresses her use of the mock self-help title in the front pages of her graphic narrative, where, in a considerate updating of the modernist faux primers by Stein and Pound, she cautions:

This is not actually a book about how to be happy. I’ve read a lot of books about how to be happy, however, and if you’re struggling, the following have been helpful to me.

Depressed and Anxious: The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Workbook for Overcoming Depression & Anxiety

BY THOMAS MARRA

Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life

BY MARSHALL B. ROSENBERG104

When asked about her how-to title by interviewers, Davis begins by confessing that “the title of the book is sort of a joke because the stories in How to Be Happy tend not to be happy at all. They are often about people struggling to be happy and not being able to succeed. It’s a painful joke. It’s a joke that feels bad to make.”105 In another interview, she offers a more complex account: “I read a lot of self-help texts. I think the struggle to be happy is an important and a noble one. The stories are a pretty motley collection written over a course of seven years, but most are about the search for happiness, the desire to be our best selves, the need to connect with other people, the struggle to become good.”106

A shifting relation to the “joke” of self-help is a common theme among contemporary writers. Hamid’s How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia began as a joke and then evolved into a more serious consideration of the self-help phenomenon.107 This inability to maintain irony or skepticism toward popular advice discourse will sound familiar to readers of Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, whose protagonist stops being able to laugh when he realizes “he is the victim of the joke and not its perpetrator.”108 Flaubert, the supreme ironist, is not afraid to laugh at self-help, but the stance of superiority such humor entails is eroded by his universalizing of self-help’s pathos, so that it ultimately applies to all “unfeathered bipeds”—whether autodidacts or university professors—seeking mastery and a way to pass the time.109 The inability to laugh at self-help may be, in part, a consequence of maturity, which brings with it the realization of the precariousness of the laugher’s superiority. In Dept. of Speculation, Jenny Offil looks back on her earlier impulse to mock those people with “their happiness maps and their gratitude journals and their bags made out of recycled tire treads.” She continues, “But now it seems possible that the truth about getting older is that there are fewer and fewer things to make fun of until finally there is nothing you are sure you will never be.”110 Never that funny to begin with, the joke of the mock self-help frame, which might be akin to what Sianne Ngai has so usefully theorized as the “gimmick”—something that offends in the aesthetic because it seems simultaneously too easy and as if it is trying too hard111—evolves, for all of these authors, into something deeper: a manifestation of the “noble” spiritual search that consumes us all. In traversing the joke of self-help, these authors shift from satirists to accomplices in the quest for a meaningful existence.

JANUS-FACED SELF-HELP

Scholars of self-help would do well to follow the lead of contemporary authors in moving beyond automatic skepticism of the industry and recognizing, as Rita Felski puts it, that “the pragmatic … neither destroys nor excludes the poetic.”112 Instead, though, “between the one-sided exaltation of self-help literature on the part of authors with books to sell and the blasé rejection on the part of the intellectual elite, there is a vacuum.”113 Self-help’s ability to elicit such polarized responses may be due to its inherently “Janus-face[d]” character, as sociologist Micki McGee calls it.114 Self-help became the target of a fairly sustained academic attack in the early twentieth century. Thinkers from Theodor Adorno to Michel Foucault have derided self-help as a form of narcissistic self-indulgence and as a “technology of the self” meant to depoliticize individuals for the sake of social control.115 The question of whether self-help can spur subversive or revolutionary political practice has been at the core of academic debates over the genre. Scholars fall roughly into two opposed camps of critical theory and reader-response-based cultural studies.116 In addition to Adorno and Foucault, subscribers to the former position, including T. J. Jackson Lears, Christopher Lasch, and Lauren Berlant, have been reluctant to acknowledge the idea that self-help could incite positive political change, arguing that it tends to domesticate, rather than inflame, transgressive appetites.117 At times my research draws upon and indeed often corroborates such critiques, but it also builds upon the work of minority, feminist, and reader-response scholars who maintain that there is more to the story of self-help than its status as an index of a narcissistic, self-indulgent culture, as a force that paralyzes those it claims to help, and as an agent that fosters privatized solutions to systemic problems.

In contrast to the cultural theorists just mentioned, feminist critics, in particular, have been vocal about the genre’s political potential. Following the work of Janice Radway, they have been suspicious of the scholarly construct of a passive, indoctrinated popular reader.118 Arlie Russell Hochschild describes self-help “with optimism” as a “prepolitical stance,” a view that McGee extends when she argues that “the ideas that self-improvement literature is premised on—self-determination and self-fulfillment—continue to hold political possibilities that might be tapped for a progressive, even radical, agenda.”119 Verta Taylor concurs, focusing specifically on the emancipatory potential of self-help for feminism; as she puts it, “self-help is the distinctively postmodern project that allows women to combine the tenets of feminism with the professional discourses of medicine, law, psychology, therapy, and the social sciences in the ongoing struggle to reconstitute the meaning of the female self.”120 In a comment that applies to self-help, Audre Lorde writes that “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”121 Although women are often cited as the historical victims of the cultural obsession with self-betterment, it is women critics who have most vocally defended the genre’s influence, along with the working-class readers who repeatedly aver the constructive personal impact of self-help texts. Treating such positive accounts as a sign of the extent of these groups’ indoctrination by the self-help ideology, rather than granting their perspectives insight into the genre’s consequence, risks perpetuating self-help’s own alleged co-optation of these voices.

In addition to feminist criticism, another sphere that invites a more nuanced approach to self-help is African diasporic studies, where the literature’s Janus-faced status as both a necessary tool for self-reliance and a vehicle of oppressive pathologizing comes starkly into view. The status of self-help in African Anglo-American culture has been explored by scholars including Paul Gilroy and Henry Giroux and, to a degree, can be said to inform Afro-pessimism’s negation of the affirmative, triumphalist, and redemptive rhetoric used to narrate black experience, such as is found in self-help. Articulating the standard critique, Giroux emphasizes the way self-help “displaces responsibility for social welfare from government to individual citizens,” with the “discourses of self-help and demonization” together conspiring to pathologize and individualize the social causes of racial inequality.122 Gayle McKeen complicates this reading by pointing out that “self-help has deep roots in and enduring importance for African-American culture. From the beginning of their life in America, blacks ‘helped themselves’ through church groups, secret societies, mutual aid and insurance societies, cooperative businesses, and benevolent societies.”123 Initially associated with the message of “uplift” advanced by Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Marcus Garvey, among others, self-help became at once a tenet of black nationalist groups and, later, a motto of neoconservative African American thinkers such as Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, and Thomas Sowell.124 The multifaceted quality of self-help is evident in black literary engagements with the phenomenon as well, from W. E. B. Du Bois’s endorsement of Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s series of self-help pamphlets, known as the Little Blue Books, which became a key resource for African American autodidacts, and for which Du Bois himself wrote two booklets,125 to Richard Wright’s calls for “self-help in negro education.”126 My final chapter addresses the tradition of African American self-help in relation to the contemporary writings of Baratunde Thurston and Terrance Hayes, but in general this book pursues a global diasporic trajectory—from the Onitsha pamphlets and Chris Abani’s GraceLand to considering self-help’s Middle Eastern, Chinese, and Japanese manifestations.127

Self-help has been a target not only of academic scorn but also of the public-intellectual polemicists who have extensively documented the industry’s shortcomings. Todd Tiede, Wendy Kaminer, Barbara Ehrenreich, and Steve Salerno, for example, have all launched cutting invectives against the consequences of self-help’s startling ascent.128 To begin, they cite self-help’s contribution to our culture of anxiety and overwork, which leads to what McGee calls the “belabored self” of modernity.129 Even more troubling is self-help’s erasure of the systemic and subsequent dampening of the people’s ardor for social reform, a move with the worst consequences for the poor and disenfranchised. For instance, self-help embodies the ethos of individual accountability that must be overcome in order for the welfare state to prove its necessity. In the writings of Adorno and West, it often appears as a harbinger of the transition from democracy to fascism, a lineage that now seems a little too real in view of Donald Trump’s long-standing devotion to Norman Vincent Peale’s Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan. (In The Power of Positive Thinking [1952], Peale advises his readers to “always picture ‘success’ no matter how badly things seem.”) It is Peale whom Trump credits with instilling his “positive” outlook and unbridled confidence in the idea that he could become anything he desired.130 Probably Ehrenreich herself could not have invented better proof that positive thinking has ruined America.

My own approach to self-help’s history hinges upon an insight that is essentially sociological: that situated practice is worth pursuing as an object of inquiry regardless of whether the research authorizes this practice or not. In so doing, it builds on the dialectical understanding of self-help advanced by African American and feminist critics. Though the term dialectic can seem like a euphemism for a problem that is simply unresolved, it is the most apt description of my method of engaging with the Janus-faced character of self-help as both a tool of ideological oppression and a potentially productive vector of consolation, community, and self-transformation, much like many other popular media.

Without undermining the value of the anti-self-help polemics, my own focus is on the question of what else self-help accomplishes and what is left out of these dominant accounts of the industry. Chiefly, commentators have neglected to take account of self-help’s role as a purveyor of a literary counterhistory in which reading is not cataloged according to historical period or genre but according to personal need. By examining a slew of popular self-help authors from the nineteenth century to the present day—those typically overlooked by cultural histories of the development of modern subjectivity—this book presses on the academic suspicion toward discourses of agency and self-cultivation that has until recently defined the overwhelming current of scholarship on this topic.

Self-help is a vehicle for the romance of upward mobility, but it also designates a mode of reading and appropriating the wisdom literature of the past. Wisdom literature may sound a little archaic to some scholars, and that is part of the point. At a time when moral humanism has fallen out of academic fashion, self-help readers and writers have become custodians of the canon of practical thought. The cultural work self-help performs is fraught with political consequence. Self-help’s emulative reading methodology has a surprising political history of inspiring the formation of radical readers in countries across the globe, from U Nu, the first prime minister of Burma, who translated Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People into Burmese, to the young Iranian feminists reading pirated copies of John Gray’s Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus.131 Far from passively assimilating capitalist values and hierarchies, readers around the world have pivoted from encounters with classic self-help texts to agitating for political independence and contributing to nationalist cultural initiatives. By putting on hold the standard critique of the genre’s homogenous influence, this book is a step toward recalibrating the scales by which we measure self-help’s literary and political relevance.

Of course, saying that the influence of a group of texts is universally good is as hyperbolic as saying that it is universally bad, an important reminder for humanists as well as ideology critics. For every U Nu, in other words, there is a Charles Manson, who was also apparently a Carnegie fan.132 This inquiry suspends the question of whether self-help is inherently good or bad to explore how it is received and implemented in specific cultural contexts. In practice, most readers approach self-help relationally, and with a grain of salt. This is not to deny that self-help is guilty of all of the charges laid against it but to point out that we are reluctant to attribute to it the heterogeneous cultural influence allotted to many other cultural forms. If advertising, cinema, television, genre fiction, and comic books are worthy of nuance and attention, the same may be true of self-help. At least some of our most lauded contemporary authors, from Zadie Smith to Mohsin Hamid, believe as much.133 Scholarship lags far behind their aesthetic considerations of the industry’s global and personal consequence.

ARCHIVE OF A NONEXISTENT GENRE

Research for this book has confronted, on the one hand, an unceasing deluge of new self-help guides to everything under the sun and, on the other, complete disorder and inconsistency in cataloging procedures for archival self-help materials, many of which have been lost as a result. Gotham Books publisher William Shinker, discoverer of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, notes as late as 2013 that “there isn’t even a category officially called ‘self-help.’”134 The nebulousness of the genre has led self-help’s archive to be arbitrarily filed under psychology, religion, finance, nutrition, business, and home design.

The preservation of self-help’s archive is so patchy, disorderly, and complex that two academic librarians use the New Thought movement as a case study of the challenges facing acquisitions librarians seeking to establish a new university collection. As John Fenner and Audrey Fenner note, “libraries … have routinely weeded their New Thought collections, treating the material as popular genre or polemical literature of passing interest.” In addition, “many early volumes of New Thought periodicals have been lost through the failure of libraries to maintain continuous subscriptions or to purchase back issues.”135 Needless to say, all of these challenges facing acquisitions librarians also confront literary scholars who are conducting inquiries into this incredibly ubiquitous and yet diffuse movement.

One cannot simply type “self-help” into a finding aid with the date parameters in question and be presented with relevant material, so this research has often been guided by the bespoke archival initiatives of hobbyists, by leads in advertisements to books that can no longer be found, and by references to lecturers whose ideas were so popular and pervasive that no transcripts have been saved. It is a culture pieced together though literary allusions, correspondence course ephemera, family scrapbooks, and back-page mail-order advertisements.

Other obstacles also exist to reconstructing self-help’s early circulation and reception. Among them is the fact that “the lives of most non-professional readers remain unpreserved by the archive,” as Amy Blair observes.136 Added to this is the stigma associated with self-help reading, which was typically relegated to the individual’s “Secret-Shelf collection”137 and often was not reported in surveys of reading habits.

Our current knowledge of self-help’s history represents a division of labor among select sociologists, Americanists, and scholars of cultural studies and religion. The nationalized silos of academic scholarship have impeded the study of self-help’s history. Specialists in American studies have written the most useful extant histories of self-help, which unsurprisingly tend to focus on an American canon, a trend that perpetuates engrained omissions of the longue durée cross-cultural exchange that was integral to the industry’s formation. The popularity of self-help in the United States should not obfuscate its international manifestations, which even in English exist under several designations: self-culture, aspirational culture, conduct literature, personal growth, and the literature of success. In China, where self-help dominates the shelves of local bookstores, one finds references to “chicken soup books,” after Jack Canfield’s popular series;138 in France, self-help guides can be found under the headings “vie pratique” (practical life) or “développement personnel” (personal development).

Even the index of the massive A History of the Book in America, the ostensive birthplace of the industry, skips from “self-censorship” to “Sendak (Maurice)” with nary a mention of self-help. This omission is even more puzzling when we learn that volume four of this series, covering the years of self-help’s consolidation, seeks to explain how “in our period, contending parties sought to broaden and diversify literacy training and education and to exploit new mass production technologies in order to challenge the traditional connection between books and educated elites”—precisely the causes and conditions of self-help’s ascension.139

Literary critics and book historians have remained largely quiet on the subject of self-help, but scholars have come up with a variety of terms to describe the strategies of the aspirational reading classes: Darnton’s “segmental” reading, Mortimer Adler’s “action reading,” Michel de Certeau’s “poaching,” Louise Rosenblatt’s “efferent reading,” and Amy Blair’s “reading up.”140 The self-help compulsion bears affinities with all of these methods. In the name of pragmatism, self-help books gamely pluck passages from their historical context and implicitly encourage readers to do the same. In this respect, self-help models a mobility and textual agency that has been relegated to the margins of professional literary criticism.

THE SELF-HELP COMPULSION IN SIX STEPS (OR CHAPTER SUMMARIES)

This book’s trajectory is guided in part by the temporal and geographic nimbleness of the self-help readers it describes. It impudently traverses vast terrains of time and space, like the readers it studies, finding common patterns of experience and attention in reading communities from disparate locales. I do this partly in an effort to keep up with the globetrotting history of self-help itself. Self-help is a medium in which, as Jeffrey Kenney puts it, “the Qur’an and Michel Foucault contribute to the discovery of the self,” and “a motivational epigram from Gandhi can be followed a few pages later by a quote from ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, and still later by one from Jean-Paul Sartre.”141

I engage in temporal leaps as well as geographic ones. This is in part due to the uneven delays of travel and importation, as exemplified in the deferred global reception of Smiles’s Self-Help (see chapter 1). In pursuing such leaps, The Self-Help Compulsion is an experiment in imagining and enacting alternatives to a strictly chronological methodology, and, to a degree, it can be aligned with the growing chorus of scholars questioning the usefulness of periodization in literary study.142 I was spurred to adopt this approach less out of any strict methodological conviction than out of the realization that the historical and geographic dynamism of self-help would be impossible to capture through any narrowly chronological or nationalist approach. Although the brazen textual leaps and unlikely cultural connections self-help brings to view may initially feel disconcerting, I hope my readers can countenance a little bit of choppiness as a necessary induction to—and immersion in—self-help’s irreverent method.

As I argue, handbooks such as Smiles’s Self-Help and Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People have historically operated as cultural ambassadors, introducing readers around the world to the intellectual tradition through their hodgepodge of citations. Chapter 1 introduces the cultural wormhole that is self-help’s collapsing of period, nation, and genre by demonstrating the way Smiles’s work specifically, and the self-help hermeneutic more broadly, were adopted and popularized throughout the world—with particular analysis of Smiles’s influence in Japan, China, and Nigeria. It argues, through a concluding discussion of Tash Aw’s Five Star Billionaire, that the patchwork, utilitarian method of the industry’s early readers continues to inform self-help’s global circulation.

Chapter 1 outlines self-help’s overlooked cultural influence, and this influence is precisely what made the rising industry so threatening to the staunch aesthete Gustave Flaubert as early as the late nineteenth century. Flaubert’s final novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet (1881), offers one of literary history’s most merciless takedowns of the pathos of self-help’s pseudo-activity, bringing the class dynamics of self-help’s aspirational promises into full view. After inheriting a sudden windfall, Flaubert’s middle-class characters quit their day jobs as copy clerks to move to the country and pursue their hobbies full time; they dabble in landscaping, philanthropy, canning, homeopathy, and more, always with abysmal results. Through a close reading of Flaubert’s novel and its neglected guidebook intertexts, chapter 2 examines a key moment in self-help’s history, when the industry shifted away from its working-class, radical origins to become a domestic pastime of the bourgeoisie. Described as a great “how not to” book, Bouvard and Pécuchet sets the pattern for future literary engagements with self-help discourse and practice.143

Chapter 3, “Negative Visualization,” broadens the focus to survey a variety of early twentieth-century responses to self-help’s consolidation into a formidable textual industry. In particular, I revisit Henry James’s “The Jolly Corner” (1908), Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), Edith Wharton’s Twilight Sleep (1927), and Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman (1939) to lay bare the commitment to unsettling early self-improvement axioms that underlies these authors’ diverse textual pedagogies. Though the rarified ambitions of these novelists seem diametrically opposed to self-help’s instrumental materialism, I suggest that they both sprang from similar efforts to cope with the competition and overstimulation of urban experience. Moreover, each movement was responding to the other’s version of textual counsel, and I argue that it is impossible to fully understand the pedagogic impetus of either the modern novel or self-help without reference to the competing movement’s didactic and philosophic practice.

Chapter 4, “Joyce for Life,” uncovers a tradition of populist commentators who advocate approaching James Joyce’s Ulysses as nothing less than a self-help manual. Like Joyce’s populist critics, the characters in Ulysses read books not for pure aesthetic enjoyment but for practical use. The problem of reading for use versus for appreciation was a hotly contested issue in Ireland during Joyce’s day. This chapter uses Joyce’s oeuvre to reveal self-help reading methods as a continuum that unites critics and lay readers, entrepreneurs and aesthetes, politicians and revolutionaries.

Chapter 5, “Modernism Without Tears,” explores three unlikely examples of the convergence of high, serious literature and self-help: first, Alain de Botton’s and Theodor Adorno’s surprisingly complementary readings of Marcel Proust; second, the interpretations of Nathanael West’s experimental story Miss Lonelyhearts by practicing advice columnists Dear Abby and Ann Landers; and third, readings of Samuel Beckett as a model for corporate creativity. I ask what happens when modernism meets with contemporary readers who refuse to accept its antididactic pose.

The piecemeal methodology of self-help’s early readers around the world, who mined authors from Shakespeare to Ibsen for their practical insights, has become a structural device of the contemporary fiction of Mohsin Hamid, Tash Aw, Sheila Heti, Charles Yu, and more, as I address in chapter 6. These authors are attracted to the self-help focalization for precisely what previous authors disliked—the way it implicates the reader in the story being told. Contemporary novelists have caught on to the point made by one of the readers in Simonds’s study of self-help for women: “With the novel, you can forget yourself a little bit, it’s like watching a movie…. The self-help book is piercing right into you…. You’re always—you’re reading the book—but you’re looking at the book separately and objectively, saying, ‘How does this impact on me?’”144 These authors continue the critiques of self-help that Flaubert and his modernist successors began, but they resist the stance of superiority, impersonality, and disinterestedness that earlier authors adopted toward the industry. For them, self-help becomes a vehicle for posing important questions about how to most fully embody and appreciate transient experience.