9 To Know and How to Use Object Pronouns

Skepticism is very French. As Montaigne said, “Que sais-je?” To be able to dissect this profound question, you’ll need to understand the differences between savoir and connaître, which both mean to know. But to say “I know it,” you’ll also need to learn about direct and indirect object pronouns. This will be a challenge, but once you get a grip on the ordering of object pronouns, you’ll finally get to say “I know it!”

Savoir vs. Connaître

Both savoir and connaître mean to know, though they are used differently.

Savoir

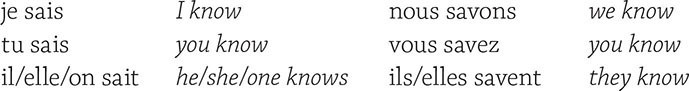

Savoir means to know a fact or to know how to do something from memory. This is how it is conjugated in the present tense:

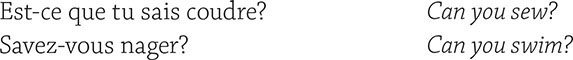

Here are some sample sentences:

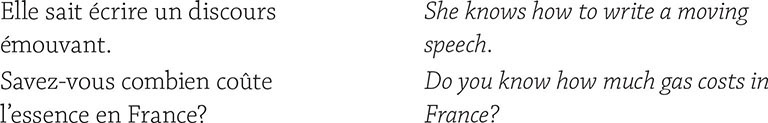

Savoir is also used before before an infinitive or before a dependent clause.

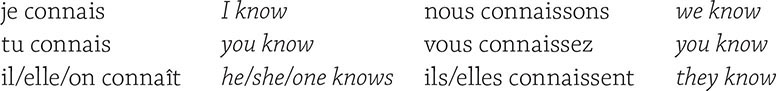

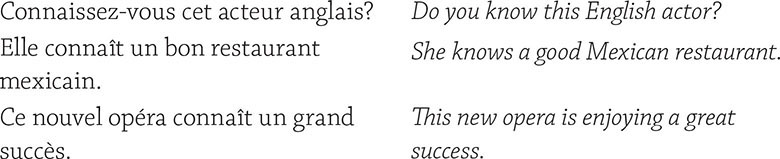

Connaître

Connaître means to know, to be acquainted with, or to be familiar with. It also means to enjoy or experience. It is always followed by a direct object, never by a dependent clause.

Here are some sample sentences:

Direct and Indirect Object Pronouns

Because object pronouns replace a noun that is being acted on, shared knowledge of the topic is presumed when using it. In this way, they help us to avoid repetition and be more concise. There are two types of object pronouns: direct and indirect.

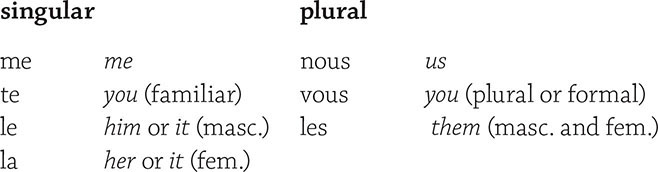

The Direct Object Pronoun

In English there are seven direct object pronouns: me, you, him, her, it, us, and them. Because of the distinction between tu and vous, in French there are eight direct object pronouns instead of seven. While in English there is a distinction between a direct object pronoun that replaces a person (him, her, or them) and a thing (it or them), in French le, la, and les can replace both people and things.

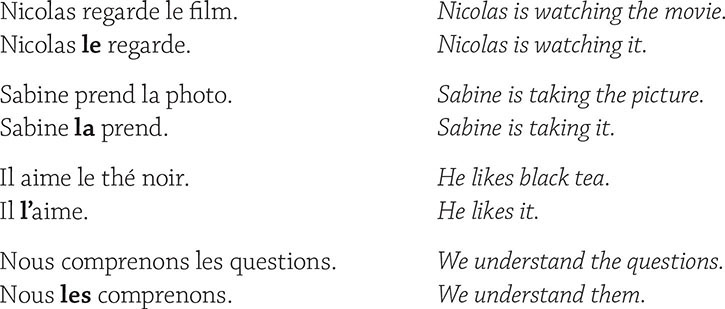

An object is called direct if it immediately follows the verb without a preposition. The direct object pronoun replaces the direct object noun. In French, the direct object pronoun must agree in gender and in number with the noun it replaces. And it precedes the main verb of the sentence.

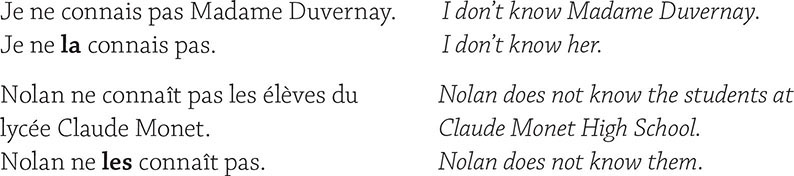

Note that when there are compound verbs, the placement of the direct object pronoun may change. But for now, keep it directly before the main verb. Here are some examples of how they are used in the third person:

When used in a negative sentence, the direct object pronoun comes immediately before the conjugated verb.

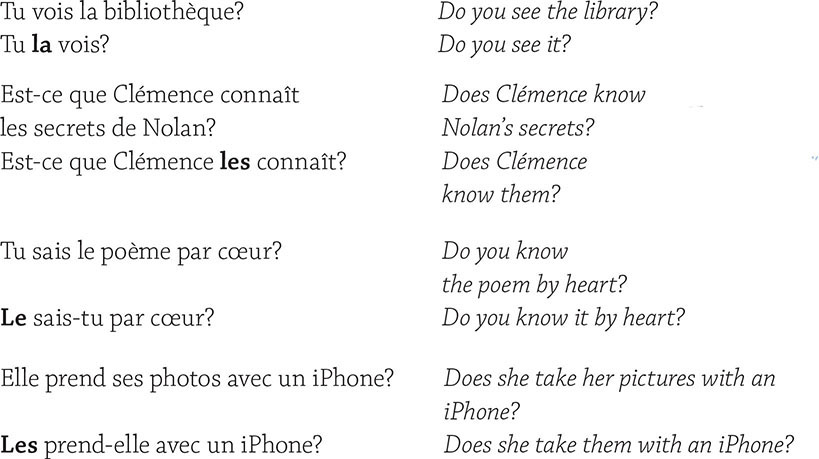

When used in a question, the direct object pronoun also comes before the conjugated verb.

Remember that direct object pronouns can also be used in the first person and second person, both singular and plural. And it follows the same rules as le, la, and les.

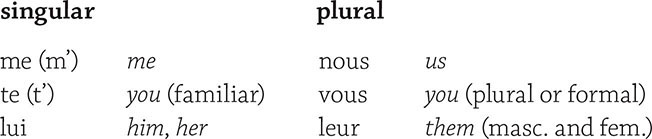

Indirect Object Pronouns

In English, there are seven indirect object pronouns: me, you, him, her, it, us, them. As always, French distinguishes between an informal you (tu) and a formal and/or plural you (vous). But the French indirect object pronouns do not specify gender. Lui and leur replace all nouns, both masculine and feminine. Furthermore, inanimate ideas and things are replaced with the indrect object pronouns y and en, which will be mentioned later in the chapter.

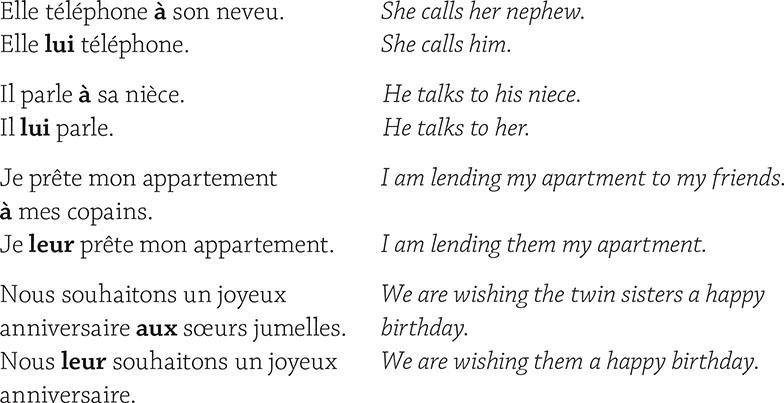

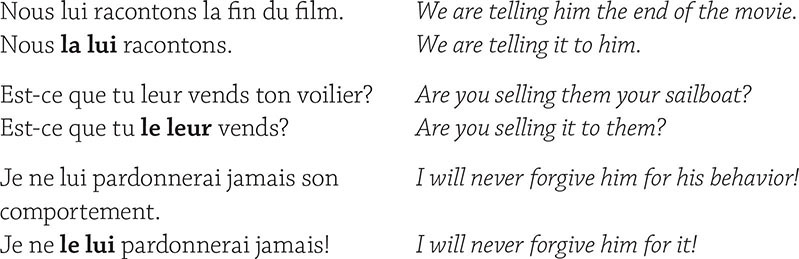

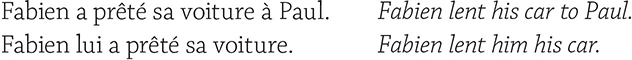

The object is labeled indirect when the verb is controlled by a preposition (parler à, écrire à, etc.), and the indirect object pronoun is placed before the conjugated verb. And in cases where there are compound verbs, it goes before avoir. Finally, remember to distinguish between leur, the indirect object pronoun, and leur(s), the possessive adjective. Here are some sentences using indirect object pronouns in the third-person singular and plural:

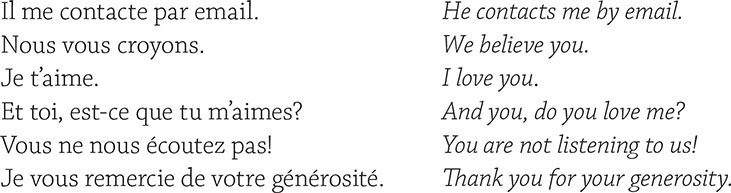

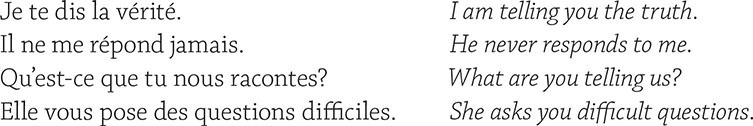

Now let’s add the indirect object pronouns me, te, nous, and vous into the mix.

Remember that when object pronouns precede a verb beginning with a vowel, me and te become m’ and t’.

The Order of Object Pronouns

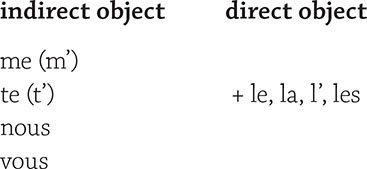

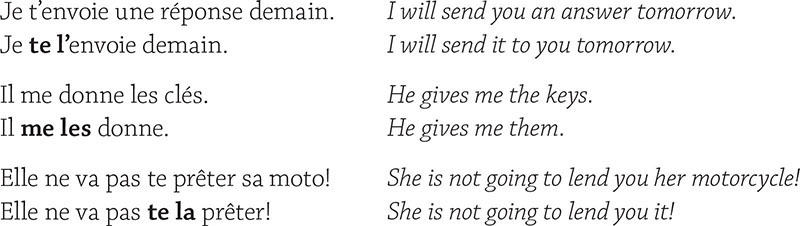

When a direct and indirect object pronoun are combined in the same sentence, the indirect object pronoun comes first, unless the direct and indirect pronouns are in the third person. In this case, the direct object pronoun comes first.

The first-person and the second-person pronouns are:

The third-person pronouns are:

Restrictions on the Use of Object Pronouns

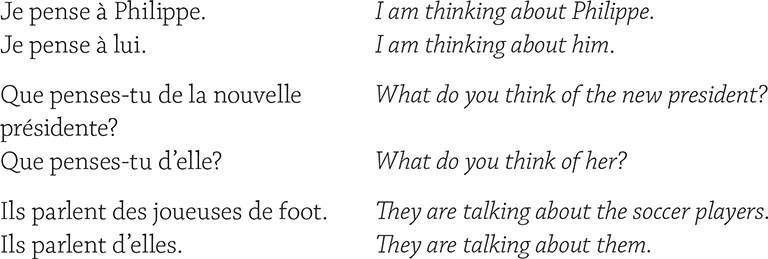

Some verbs followed by the preposition à or de do not follow the aforementioned rule. Instead of an indirect object pronoun, a stressed pronoun (moi, toi, lui, elle, nous, vous, eux) comes after the verb. And depending on the preposition, the meaning of the verb may change; it is just a matter of memorizing.

En and y

Here’s a simple trick: y goes with à, and de goes with en. You can think of them as grammatical shortcuts for not repeating objects.

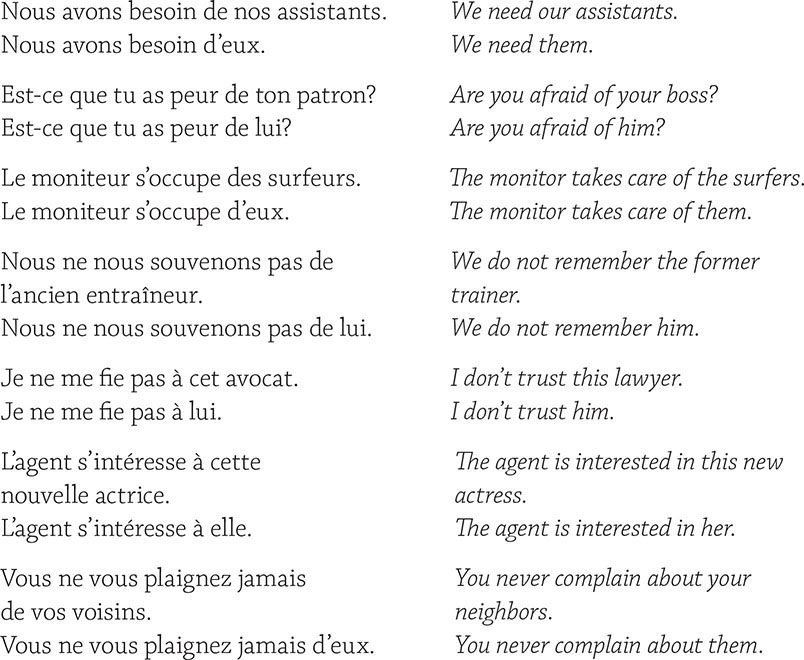

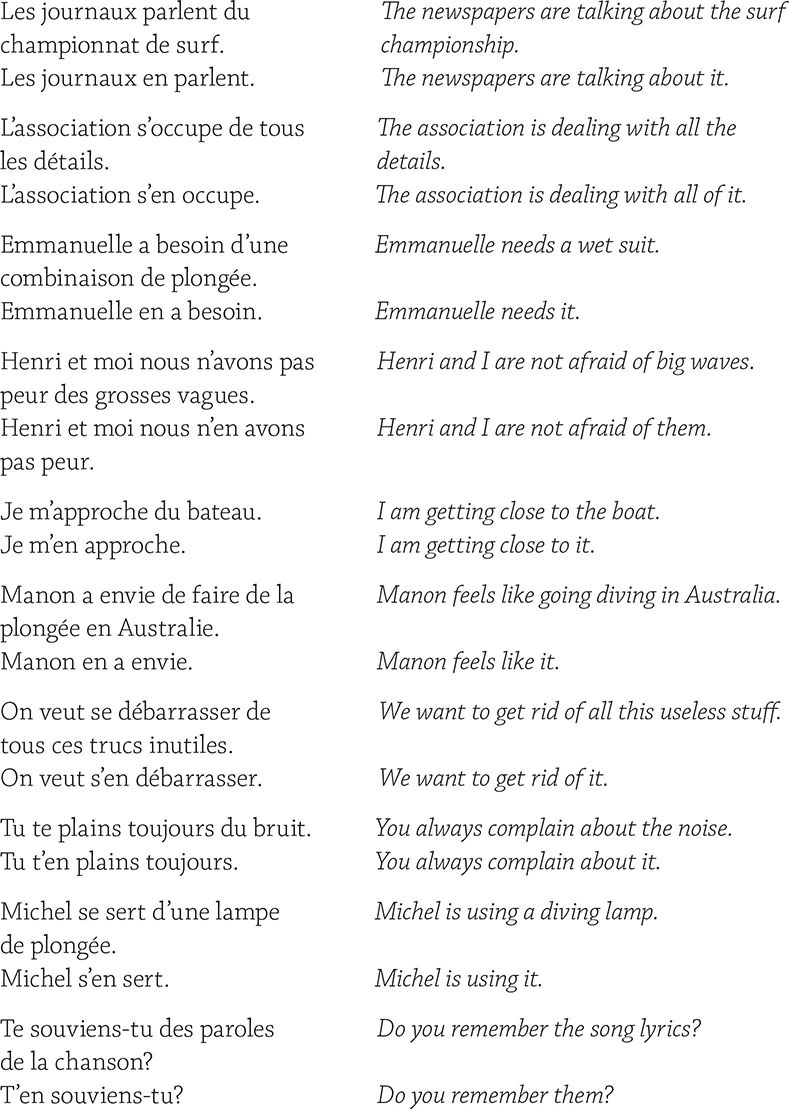

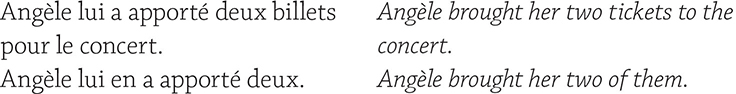

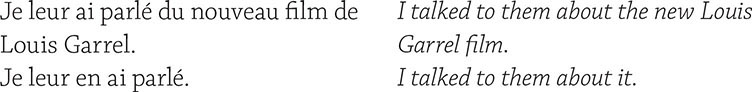

The Pronoun en

En is an indirect object pronoun that precedes the verb. It usually replaces an inanimate object (thing or idea) preceded by de. The pronoun en immeditately precedes the verb, except in affirmative imperative commands. In this case, en follows the verb and is connected with a hyphen. And with pronominal verbs, the en goes right after the reflexive pronoun.

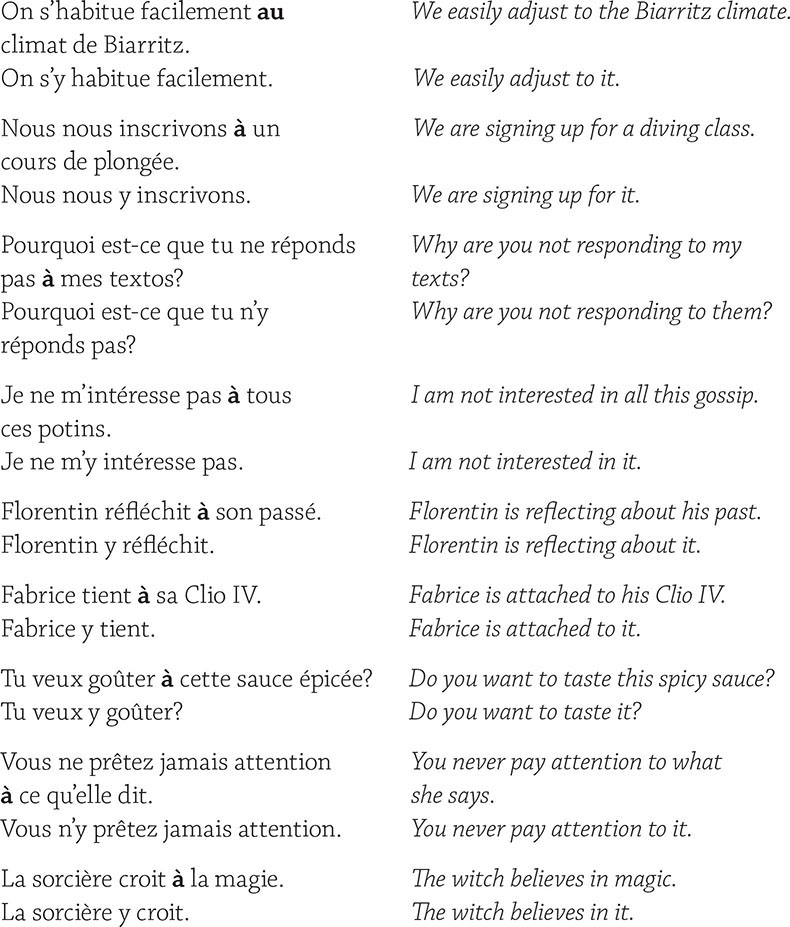

The Pronoun y

Y is also an indirect object pronoun that precedes the verb. It usually replaces an inanimate object (thing or idea). The object replaced by y is considered indirect because it is preceded by a preposition, usually à. And it follows the same gramatical rules as en.

Object Pronouns with Compound Tenses

Now it’s time to mix and match what we just learned with the passé composé. The two most important items to remember are the placement and order of the object pronouns, as well as possible agreements with avoir.

Direct Object Pronouns

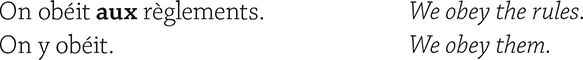

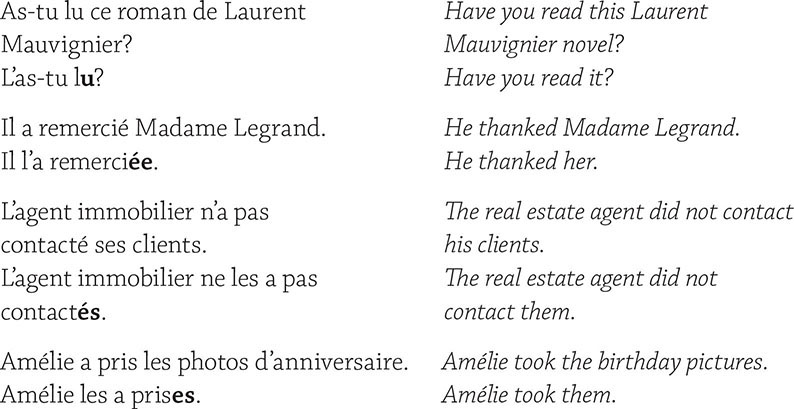

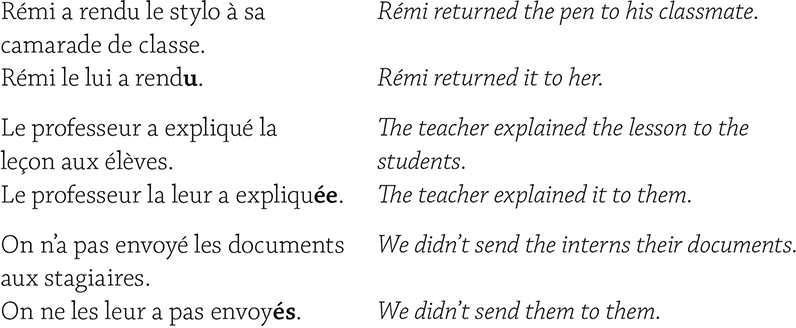

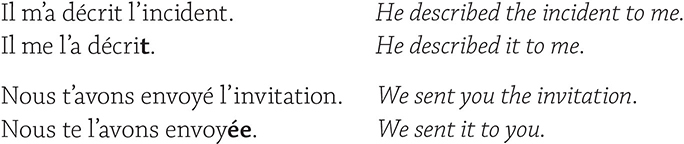

In the passé composé and other compound tenses, the direct object pronoun is placed before the auxiliary verb. The past participle agrees in number and gender with the direct object when the direct object precedes the verb.

Indirect Object Pronouns

Like direct object pronouns, when indirect object pronouns are combined with compound tenses, they are placed right before the auxiliary verb. But unlike direct object pronouns, the participle is not modified to make it agree.

When direct and indirect object pronouns are combined with compound tenses, the participle is modified to agree with the direct object pronoun, and it follows the order rules found in the chart above.

And remember that the order changes when dealing with the first person and second person, both singular and plural.

When en is combined with an indirect object pronoun, it is always in the second position. The past participle agrees neither in number nor gender with en (nor does it agree with any other indirect object pronoun).

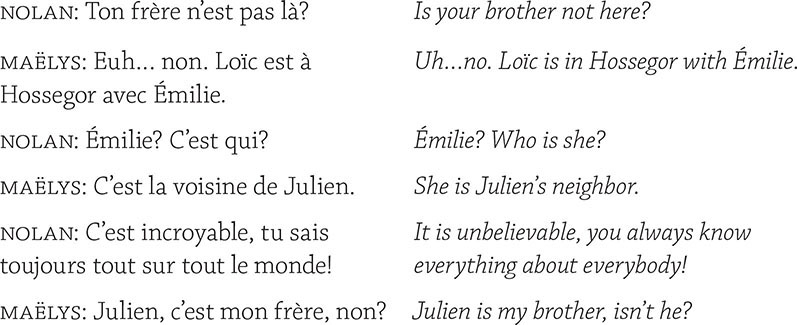

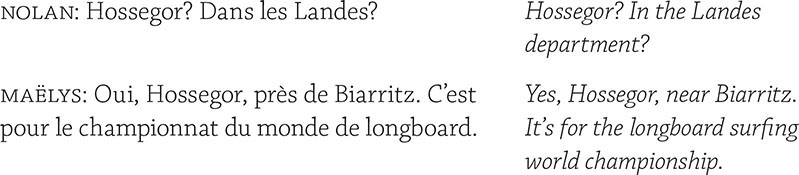

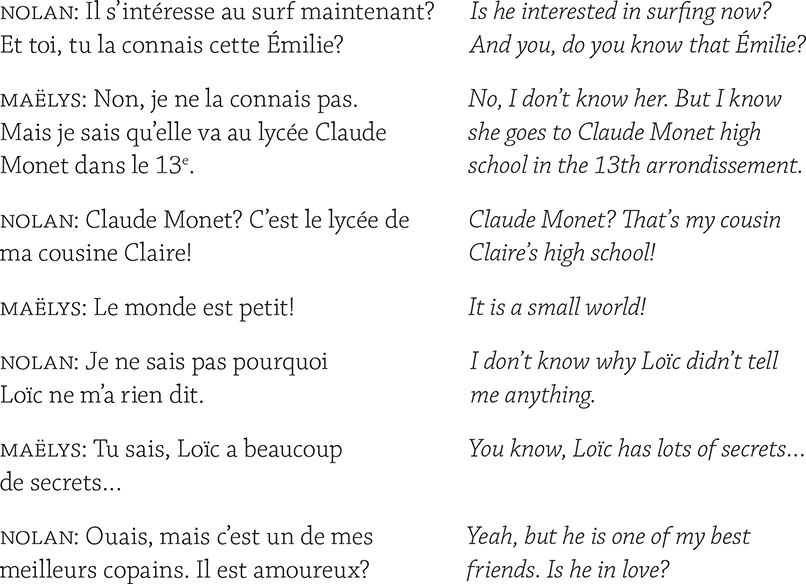

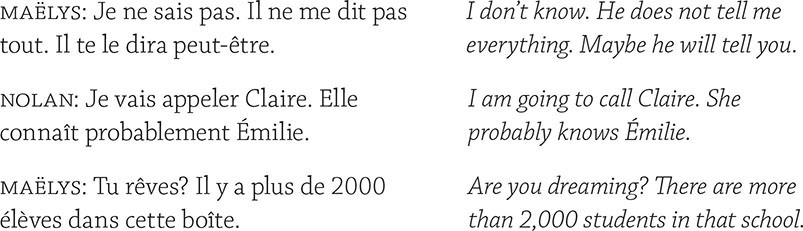

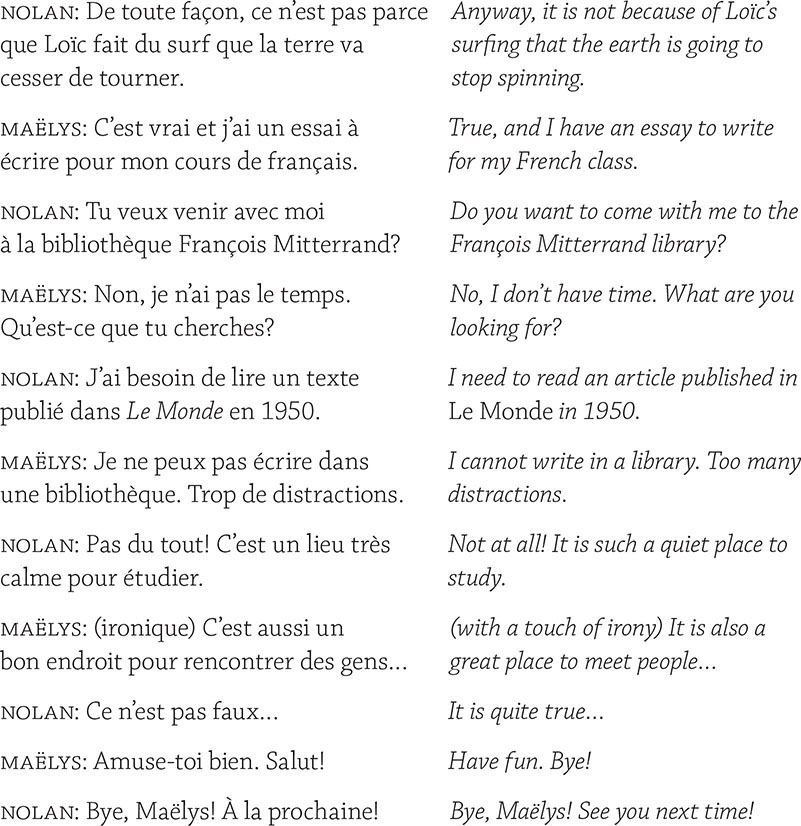

DIALOGUE Après-midi de bavardages! Some Afternoon Small Talk!

DIALOGUE Après-midi de bavardages! Some Afternoon Small Talk!

Maëlys and Nolan are talking in front of their school, the lycée Gabriel Fauré in the 13th arrondissement. Nolan is surprised that Maëlys’ brother Loïc is not around. Time for gossip.

EXERCISES

EXERCISE 9.1

Conjugate savoir and connaître in the present tense.

1. Je (connaître) _______________ bien ce comédien.

2. Je (ne pas savoir) _______________ où ils habitent.

3. Manon (savoir) _______________ ce poème.

4. Est-ce que vous (connaître) _______________ ce nouveau logiciel?

5. Joséphine (savoir) _______________ le nom de la capitale du Kirghizistan.

6. Luc (ne pas connaître) _______________ l’histoire du Kirghizistan.

7. Gaël et moi, nous (connaître) _______________ une très bonne auberge en Dordogne.

8. Est-ce que tu (connaître) _______________ Christophe Lambert?

9. Vous (savoir) _______________ combien ça coûte?

10. Ils (savoir) _______________ de quoi ils parlent.

EXERCISE 9.2

Complete the sentences with savoir or connaître in the present tense.

1. Théo _______________ Roland depuis trois mois.

2. Est-ce que vous _______________ pourquoi il est en retard?

3. Noah _______________ parler le russe couramment.

4. Cette pièce de théâtre _______________ un grand succès.

5. Je _______________ la mère de Véronique.

6. Lucy et Hélène _______________ une excellente brasserie dans le sixième arrondissement.

7. Est-ce que tu _______________ compter jusqu’à mille en français?

8. Nous _______________ jouer du saxophone.

9. _______________ -vous un coiffeur dans ce quartier?

10. Je _______________ qu’Audric a un excellent professeur d’informatique.

EXERCISE 9.3

Translate the following sentences. When asking questions, use the est-ce que form.

1. Do you know Arthur? (tu)

2. Claire and Gaspard can speak Japanese.

3. Simon knows all the songs by Dalida by heart.

4. They don’t know if this village is in Provence.

5. How do you know Liam’s sister? (tu)

6. The new film by Louis-Julien Petit is enjoying a great success.

7. We know where the best Chinese restaurant in the 13th arrondissement is located.

8. I do not know if Oscar knows how to swim.

9. We know a software that can translate documents into ancient Greek.

10. Do you know the poem by Baudelaire called L’invitation au voyage? (vous)

EXERCISE 9.4

Rewrite the following sentences and replace the words in bold with direct object pronouns in the third person (le, la, les).

1. Les élèves comprennent l’explication du professeur d’anthropologie.

2. Suivez-vous le cours d’anglais de Madame Atherton?

3. Nolan ne porte pas la planche de surf d’Émilie.

4. Il regarde le championnat du monde de surf à la télé.

5. Le professeur apporte tous les documents pour la présentation.

6. Prenez-vous le train à la gare Montparnasse ou à la gare d’Austerlitz?

7. La famille Thominet n’invite pas le directeur du lycée à leur soirée.

8. Lola et Isabelle racontent leurs aventures en Patagonie.

9. Nous n’aimons pas les examens de géométrie.

10. Est-ce que tu appelles la nouvelle élève Angélique ou Angie?

EXERCISE 9.5

Translate the following sentences. When translating questions, use the est-ce que form.

1. I believe you. (tu)

2. Do we invite him? (on)

3. He takes it with sugar.

4. She thanks me.

5. They do not understand us. (elles)

6. We respect them.

7. He does not know them.

8. Do you see me? (vous)

9. They call me every day.

10. Why do you do it? (tu)

EXERCISE 9.6

Rewrite the following sentences and replace the words in bold with indirect object pronouns in the third person (lui, leur).

1. Il écrit à sa tante.

2. Le guide montre les sculptures de Nikki de Saint Phalle aux touristes.

3. Cette planche de surf appartient au moniteur.

4. L’employée explique aux clients comment remplir les formulaires.

5. Sylvain raconte l’histoire de « Réparer les vivants » à sa mère.

6. Pourquoi est-ce que tu donnes ton argent de poche à ton frère aîné?

7. Nous faisons souvent des cadeaux à nos arrière-grands-parents.

8. Xavier téléphone à sa copine Odile.

9. Hugo rend le roman de Maylis de Kerangal à son professeur.

10. Je ne sais pas comment répondre à Félix. C’est trop compliqué!

EXERCISE 9.7

Rewrite the following sentences and replace the words in bold with y or en.

1. Clara s’occupe des réservations d’hôtel.

2. Est-ce que tu as envie d’aller en Normandie?

3. Son copain s’intéresse aux films de science-fiction.

4. Nous pensons à nos examens.

5. Noémie ne se souvient pas de l’adresse du club nautique.

6. Pierre renonce à sa candidature.

7. Elles ne s’habituent pas à leur nouvel emploi.

8. Pensez-vous à vos prochaines vacances?

9. J’ai peur des fantômes.

10. Delphine tient à ses bijoux.

EXERCISE 9.8

Rewrite the following sentences and replace the words in bold with the appropriate object pronouns. Watch out for agreement.

1 Clément a prêté sa lampe de plongée à Yanis.

2. J’ai emprunté le dictionnaire des synonymes français à Gilles.

3. Avez-vous recommandé ce candidat au directeur des ressources humaines.

4. Sophia m’a envoyé sa lettre de motivation.

5. Ils t’ont promis une augmentation.

6. Vous avez encore fait les mêmes erreurs!

7. Alexandra a vendu son appartement à Rita et Hisham.

8. J’ai donné mon mot de passe à mon petit frère et son copain.

9. Pourquoi est-ce que Adam ne nous a pas encore servi les desserts?

10. On a mis les assiettes sales dans le lave-vaisselle.

EXERCISE 9.9

Translate the following sentences. When asking questions, use inversion.

1. Agathe knows this French song by heart.

2. Is he afraid of it?

3. Lise did not thank us.

4. We got rid of it. (on)

5. I don’t know if you remember me. (tu)

6. Romane is thinking about him.

7. The divers don’t need it.

8. Do you know Alicia’s neighbors? (vous)

9. I never got used to it.

10. Do you know who sent them to me? (tu)

LE COIN DES CRÉATEURS

BIOGRAPHÈME

Re-create fragments (real or imaginary) of the life of a writer you know, following the example below. Mark Twain, Toni Morrison, Annie Proulx, Ernest Hemingway? Choose any writer, whatever the century or the nationality.

Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras passe des heures sur son balcon à Trouville.

Je me souviens du jour où Duras m’a raconté sa vie en Indochine.

Duras aimait traverser le Mékong tôt le matin.

Elle se promenait dans les rues de la ville.

Elle…

À votre tour!

NOTE CULTURELLE

THE FRENCH PRESS: YOU ARE WHAT YOU READ, SERIOUSLY!

Much as it has throughout the world, the serious press in France has lost ground to more popular tabloids and magazines that focus on personalities and gossip rather than hard news. La presse people is the French version of People magazine–style journalism, and it has its fans. Who doesn’t love some celebrity gossip every now and then? However, let us not forget the serious press and the important role it still plays, both in paper and online.

In France, it used to be that if you saw someone reading a newspaper, you would immediately know a lot about them. In recent years, the printed press has gradually been ceding its place to digital formats, so it is not always possible to do this now, but it is still an interesting exercise in observation. What would you know? You would know something about their politics (left, right or center), whether they were interested in serious “hard” news as provided by the quality newspapers, also known as newspapers of record, or in “softer” stories of local or human interest (and gossip, of course!) as provided by the more popular papers and tabloids. If they are reading a regional newspaper but are not in that region, you might guess that it is due to nostalgia and a desire to maintain a connection with the place they come from (or, perhaps, are relocating to). You might also get an idea of their attention span, based on whether they prefer in-depth reporting and analyses or brief, more anecdotal news. However, it is probably best not to be too carried away because they may have simply picked up the paper left behind by the previous occupier of the adjacent seat on the Metro and are reading it because there is nothing else available!

Newspapers have played an important part in French history and culture. Almost all have digital editions online, making them more accessible to foreign students of French. Here are some of the names that you should know.

Le Monde is France’s most important national daily “hard news” newspaper. It was founded by Hubert Beuve-Méry on December 19, 1944, shortly after the liberation of Paris, at the request of Charles de Gaulle and has published continuously since its first issue. In its early years, the paper focused on analysis and opinion more than on news reporting, but that has changed, and it is now one of France’s newspapers of record, much like the New York Times in the United States and the London Times in the U.K. Politically, it often reflects establishment views and is considered center-left. Le Monde is the preferred daily of French intellectuals, civil servants, and academics. It provides the most detailed coverage of world events and politics, and is a major forum for political and intellectual debate and discussion. Foreign students of French often know Le Monde because, in pre-digital days, it was the French newspaper most readily available abroad. There is also Le Monde diplomatique, a monthly newspaper offering analysis and opinion on politics, culture, and current affairs. It is owned by a subsidiary company of Le Monde but has been given complete autonomy by the publisher. It is published in French but is also available in English and twenty-five other languages.

Le Figaro is a national daily newspaper published in Paris. It was founded as a satirical weekly in 1826 and takes its name from the main character in the 1778 play by Beaumarchais, The Marriage of Figaro. The editor considered it an appropriate choice since the paper, like the play, pokes fun at privilege. It became a daily newspaper in 1866. With its center-right editorial perspective, it is the most conservative of the quality newspapers of record and the one with the highest circulation.

Libération, or Libé as it is popularly known, is the third of France’s newspapers of record. A national daily, it was founded in 1973 by Jean-Paul Sartre, Serge July, and other left-wing intellectuals following the protest movement of May 1968. Initially a newspaper of the far-left, it never identified with a specific political party. According to Serge July, “the equation of Libération consisted in combining counter-culture and political radicalism.” At first, it did not accept any advertising, enabling the paper to freely express opinions. However, this was not a good financial model, and the idea was ultimately abandoned as the paper dealt with several financial crises. It also mellowed as its readership grew older, becoming a more center-left newspaper. Libé has the distinction of being the first of the major dailies to go digital with an online version.

Some Other Titles to Know

Le Parisien is a daily Parisian newspaper that covers international and national news, as well as local news of Paris and its suburbs. A national edition, Aujourd’hui en France (Today in France), covers the rest of France. Combined, they have the highest circulation among the country’s national papers. The paper was established as Le Parisien libéré (The Free Parisian) by Émilien Amaury in 1944 and was published for the first time on August 22, 1944. It was originally a paper of the French underground during the German occupation. It is not a paper of record, but rather a mid-market tabloid, similar to USA Today in the United States.

L’Humanité was founded in 1904 by the French socialist leader Jean Jaurès. From 1920 to 1999, it was first the unofficial, then the official newspaper of the French Communist Party. It has been editorially independent since 1999, but for the most part is still written, produced,

and promoted by French Communist Party members or supporters.

Les Échos is France’s equivalent of the Wall Street Journal. Established

in 1906 as a monthly publication under the name of Les Échos de l’Exportation by brothers Robert and Émile Servan-Schreiber, it became a daily in 1928, shortening its name to Les Échos. Originally focused on economic and financial news and analysis, since 2010 its coverage has

been expanded to cover other topics, such as innovations in science, technologies, green growth, medicine and health, and skills concerning marketing and advertising, management, education, strategy and

leadership, law and finance, and high tech and media. It is considered

liberal in its outlook.

L’Équipe, is a national daily newspaper devoted almost exclusively to sports. In a country that loves sports, perhaps it is not surprising that it has the highest circulation of any of France’s daily newspapers. It covers all sports but is particularly noted for its coverage of soccer, rugby, motor sports, and cycling.

KNOW

KNOW Connaître is never followed by a dependent clause.

Connaître is never followed by a dependent clause.