Heavy Cream, or Clapton Is God

Disraeli Gears was released in the United Kingdom November 2, 1967, and in the United States on December 9. It was enclosed in one of the great album jackets of the psychedelic era.

The album is now recognized as one of the defining releases of the late sixties. The American blues of the Delta and Chicago, which had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, had returned home in a much-altered form. It had emerged as British blues meets American psychedelic rock, and Eric Clapton and Cream were its leading practitioners.

The odd album title was conceived out of a conversation focusing on one of Ginger Baker’s favorite topics. Clapton was thinking about buying a racing bicycle and had a number of questions for Baker since he was the expert. Roadie Mick Turner overheard the conversation and mentioned it should have Disraeli gears instead of derailleur gears. Clapton and Baker were amused that he had substituted the name of the nineteenth-century British prime minister. The album’s working title had simply been Cream, but it was changed to cash in on the joke, and so one of the pivotal albums in rock history received a name. One can only wonder what Benjamin Disraeli would have thought about his name being better known to modern generations for this album than for his extensive political accomplishments.

The cover art was unique and innovative and remains instantly recognizable to rock fans today. Australian Martin Sharp was an acquaintance of Clapton from the time they lived in the same apartment building in Chelsea. He would create the artwork for their next release as well. His relationship with Clapton extended to the writing area, as he cowrote “Tales of Brave Ulysses” and the single “Anyone for Tennis.”

Felix Pappalardi began his run as Cream’s producer with this album. How much influence he had on the group will always be debatable, but the fact remains that he was the producer for two of the better and more enduring albums in music history. He and his wife Gail composed “Strange Brew” with Clapton, and he also contributed his talent as a session musician when needed. Pappalardi would go on to a successful, if somewhat short, producing and performing career after his time with the band ended.

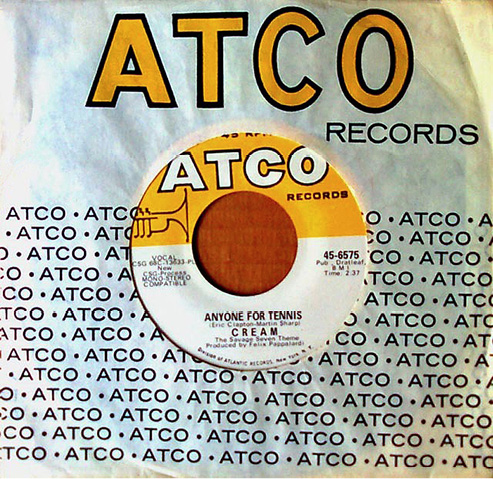

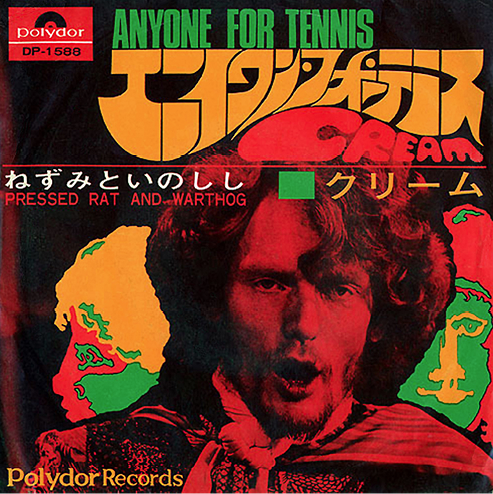

Probably the strangest single of Cream’s career.

Author’s collection

Probably the strangest single of Cream’s career with a Japan issued picture sleeve. Author’s collection

The album also marked the beginning of Clapton’s association with engineer Tom Dowd. He would also work with Dowd while with Derek and the Dominos plus during his solo career as well.

The first thing that strikes a person is the shortness of Disraeli Gears, clocking in at 33:39, and the brevity of each track. Only “Sunshine of Your Love” at 4:10 exceeded the four-minute mark, and five of the eleven tracks are under three minutes. This would be in direct opposition to their live performances, where the improvisational skills of the band would elongate the songs to ten and sometimes close to twenty minutes.

The second noticeable feature was that Eric Clapton’s name was more prominent in the credits than on their first album. He wrote three of the tracks and arranged two more. In addition, his vocals became more frequent and pronounced. While Jack Bruce was still the main vocalist, Clapton sang lead on two of the songs and was a supporting presence on several more.

The Bruce/Brown composition “Sunshine of Your Love” was the most memorable track and today is one of the songs that represents the era itself. While he did not compose it, Clapton provided a series of short notes and solos that convinced me and a generation of aspiring musicians they would never be able to play the guitar, or at least to play it well. I have seen Eric Clapton play this song live several times through the years, and for him it is effortless. This short performance would go a long way toward cementing his legacy especially in the United States. This was the band’s breakout song in the United States as it reached #5 on the singles charts and received massive radio airplay.

“Strange Brew”/“Tales of Brave Ulysses” had already been released as a single in the United Kingdom, reaching the top twenty. Both songs had been cowritten by Clapton, who also provided the lead vocal on the A-side. It was a confidence builder that his voice was strong enough to produce a hit single. Both songs are a blues/psychedelic rock fusion, and while Clapton’s playing is somewhat restrained, it is also memorable.

Arguably Cream’s most popular song. Clapton made the guitar work sound effortless. Author’s collection

The bluesiest tracks are the final three. Jack Bruce and Peter Brown went in a blues direction with “Take It Back,” and it was a good fit for the tracks that surrounded it. Clapton stayed true to his blues roots with his translations of Arthur Reynolds’s “Outside Woman Blues” and the all-too-short and traditional “Mother’s Lament.”

Disraeli Gears would be reissued in a number of forms over the years, but the 2004 Deluxe Edition contains the original album, out-takes, demos, and some live performances, which brings the album full circle.

Some highlights include the previously unreleased “Blue Condition” with a Clapton vocal. “SWLABR” was the flip side of “Sunshine of Your Love” single and contains some more excellent work by E. C. There is a shorter live version included as well. “Strange Brew” and “Tales of Brave Ulysses” are played live back to back from a June 3, 1967, broadcast on the BBC. There is also a three-song blues set broadcast October 29, 1967, on the BBC 1. “Born Under a Bad Sign,” “Outside Woman Blues,” and “Take It Back” are a fine way to spend eight and a half minutes of your life. It you want some rare Eric Clapton and Cream, this is an album for you.

Disraeli Gears would have a lasting impact upon rock music. It would reappear on the Billboard Magazine Hot 200 several times.

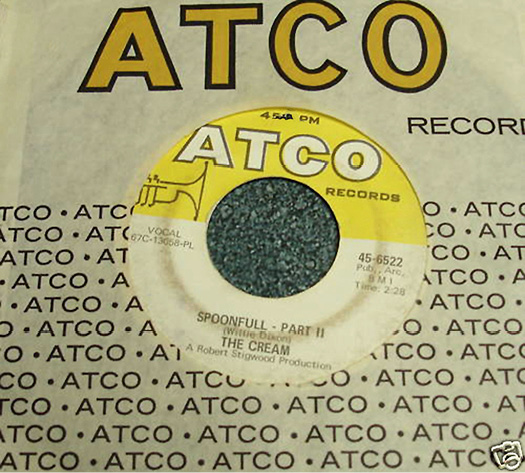

The single was good, but the extended live versions were the essence of Cream. Author’s collection

Clapton had already reached cult status before the album’s release. In February 1968, the band began a tour of the United States at the Fillmore Auditorium. This was followed by a four-night gig at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, where they shared the stage with the MC5 and the Stooges. By the time the tour was finished, Eric Clapton had become a guitar god on this side of the Atlantic as well.

Despite the commercial success, the sold-out concerts, and the adulation, all was not well with Cream. Egos were running wild, and the old animosity between Baker and Bruce had begun to resurface. These problems were especially apparent onstage, as Baker, Bruce, and sometime Clapton would try to outperform each other. Clapton commented once that it got so bad he actually stopped playing and the other two did not notice.

In the midst of all the controversy, one of the most unusual singles in their history was released. “Anyone for Tennis” is basically a pop tune and an odd one at that. It originally appeared in the film The Savage Seven. The Cream name would be the main selling point as it reached #36 in the United Kingdom. American fans were a little more discerning, as it stalled at #64.

Finally in July, Clapton had had enough. He was tired of being the go-between in the Baker/Bruce relationship or lack thereof. Baker has also had enough as his hearing was beginning to be affected due to the volume of their live concerts. They announced that Cream would disband after their current U.S. and forthcoming U.K. tour dates.

Bruce, Clapton, and Baker had been in the studio intermittently for almost a year, (July 1967–April 1968), working on their next album under the guidance of Pappalardi, who would become a virtual fourth member in the studio, adding some organ work, viola, and assorted brass that gave their music a fuller sound.

The double album Wheels of Fire was released in July 1967. It consisted of one studio disc and one live, which was recorded at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. It would be the pinnacle of their commercial success, topping the American charts for a month and becoming the first double album in music history to receive a Platinum award for sales.

In a number of countries, Wheels of Fire was released as a double album and was split into single releases as well. The U.K. Live at the Fillmore cover featured a negative image of the studio version. In Japan, the studio version was black and gold foil, and the live version was black on aluminum foil. Australian copies were laminated versions of the Japanese release. The number of variations has kept collectors busy for decades.

A couple of other interesting U.S. chart facts. The album also reached #11 on the rhythm and blues charts, which given the material was a real stretch. The album that finally replaced it at #1 was the Doors’ Waiting for the Sun, which is a good fit. The album it replaced at the top of the charts was The Beat of the Brass by Herb Albert and the Tijuana Brass, which certainly does not fit and is as far away from Cream as it gets.

For several years, Cream was constantly touring. Courtesy of Robert Rodriguez

The jacket was the second in a row by Martin Sharp, and it was another superb effort, worth finding in its original vinyl form just for the cover. It would win the New York Art Director’s prize for Best Album Art of 1969.

Eric Clapton did not take any writing credits on Wheels of Fire. Maybe he was already withdrawing from the group, but for whatever reason he limited himself to finding two old blues cover songs. “Sitting on Top of the World” and the Albert King signature tune “Born Under a Bad Sign” were the type of songs that Clapton was so adept at transforming into his own creations. Clapton later revealed that the Atlantic label had pressured the group to record “Born Under a Bad Sign” as Albert King was a label mate of the group and they thought it would be good publicity for him. Asking Eric Clapton to cover any song, especially a guitar-based blues piece, to gain popularity for the original artist always has an element of chance. “Born Under a Bad Sign” proved to be one of the more popular songs on the album, and it became a staple of their live act. I am an Albert King fan, but when this song comes to mind, I think Eric Clapton.

The two discs chronicled the schizophrenic nature of Cream’s studio work versus their live shows. The nine studio tracks were tight and controlled, ranging in times from 2:53 to 4:58. The production had become slicker than on their first two albums, and extra instruments made their appearance courtesy of producer Pappalardi. Many of the tracks had a fuller sound, with some elements of orchestration present. Except for the two blues covers, the rest of the material was more psychedelic in style.

On the other hand, when listening to the live disc, the four long live tracks were raw, improvisational, and exhausting in a good way.

The enduring song for the second album in a row would be another Bruce/Brown composition. “White Room” featured one of the smoother vocals of Bruce’s career, and the dramatic opening is an immediate attention grabber. Despite this, it is Clapton’s wah-wah sound that gives the song a unique foundation and makes it memorable. It became a top ten single in the United States.

Ginger Baker and his writing partner Mike Taylor were responsible for three of the studio tracks, and they proved Baker could be a competent composer when given the opportunity. Sometimes I think they should have made use of his composing skills a bit more, as they were closer to the original vision of the group than was the Bruce/Brown duo’s. Having said that, you certainly can’t argue with success.

“Passing the Time,” “Those Were the Days,” and the underrated “Pressed Rat and Warthog” are all nice relics of the era. When you add in a couple more Bruce/Brown compositions, “Deserted Cities of the Heart” and “Politician,” you have the makings of one of Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and that’s only the first disc.

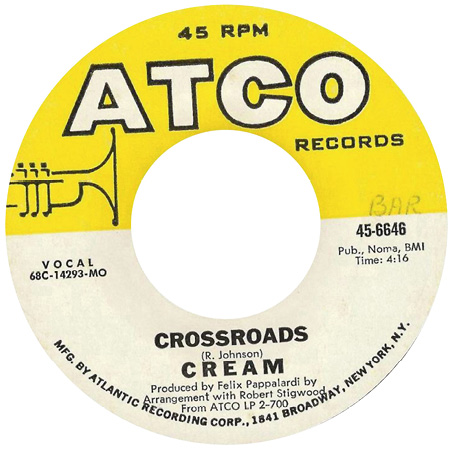

Another song that was shortened to fit the single format. Clapton continues to play the song live today.

Author’s collection

The live disc begins with a modest four-minute performance of “Crossroads.” What it lacked in length it made up for in intensity. The second of Clapton’s solos has been honored as one of his best, which means it is very good indeed. It’s tough to outplay Robert Johnson on one of his own compositions, but on March 16, 1968, E. C. came very close.

This leads to a sixteen-minute version of Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful.” This track is probably one of the most accurate pictures of Cream live as it is a group affair with Clapton weaving his guitar artistry in and out.

“Toad” was elongated to over sixteen minutes and contains the drum solo of Ginger Baker’s career, which means one of the best in rock history. Drummers have been influenced by this track for years. I get exhausted listening to it and cannot image a human being playing it live in one take.

The longer live disc is an acquired taste. It does contain a number of treats, but I have found that allowing some time between listens adds to the enjoyment.

Eric Clapton remained busy with short outside projects as his career with Cream came to a close. He took his Les Paul into the studio with George Harrison and the Beatles to play lead on his “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” He also lent a hand on Harrison’s solo effort Wonderwall Music. Clapton would be a lifelong friend of Harrison, and the relationship would survive illness, addictions, and even wives. He would organize a memorial concert in memory of Harrison after his death.

Wheels of Fire was a part of rock history as Cream embarked on their final tour.