3 Running in the Cage

In order to escape the parental home, Hank accepted the first job he found which was with the Sears Roebuck department store on Olympic Boulevard in LA.

So began Bukowski's experiences as a wage slave.

In order to escape the parental home, Hank accepted the first job he found which was with the Sears Roebuck department store on Olympic Boulevard in LA.

So began Bukowski's experiences as a wage slave.

‘This would be one of my first lessons. They expected people to give their entire lives, and all their loyalty, to some shit job.’

But the employers were not the only ones to blame:

‘...don't kid yourself—many people want SLAVERY, a job, 2 jobs, anything to keep them running in the cage.’

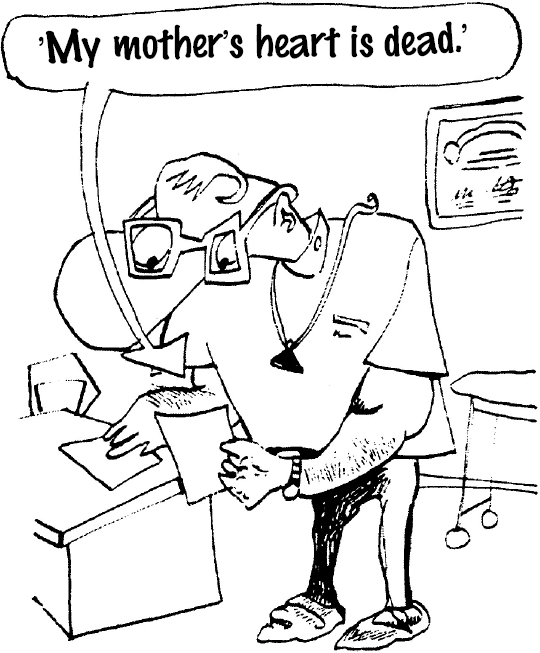

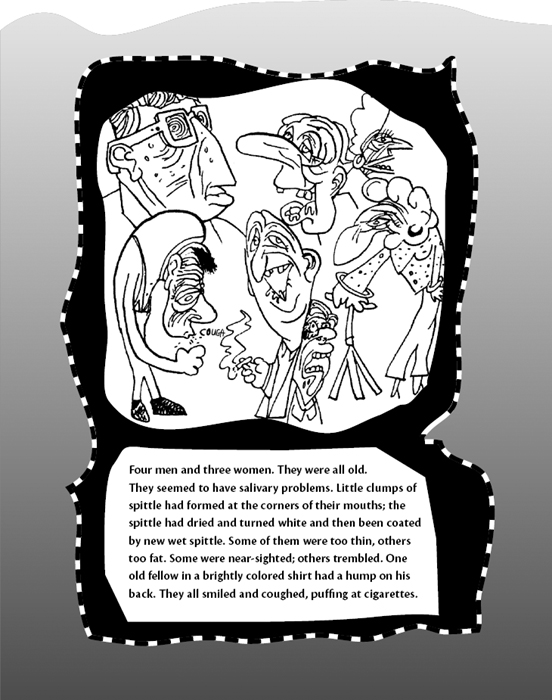

The young would-be writer had little respect for his workmates, who were of his parents’ generation. In 1982, he would describe them in the novel Ham on Rye:

He did not last long in his first job. However, he had, in 1940, enrolled at Los Angeles University. At City College on Western Avenue, his gaunt appearance caused a stir and his air of superiority did not go down well. But Bukowski created a distinct impression.

He signed up for several courses including journalism, dramatic art, English and history. He felt it would not be a bad idea to earn his living as a journalist. In the end, it was all writing. But it would be twenty years before he would write regularly for a daily newspaper.

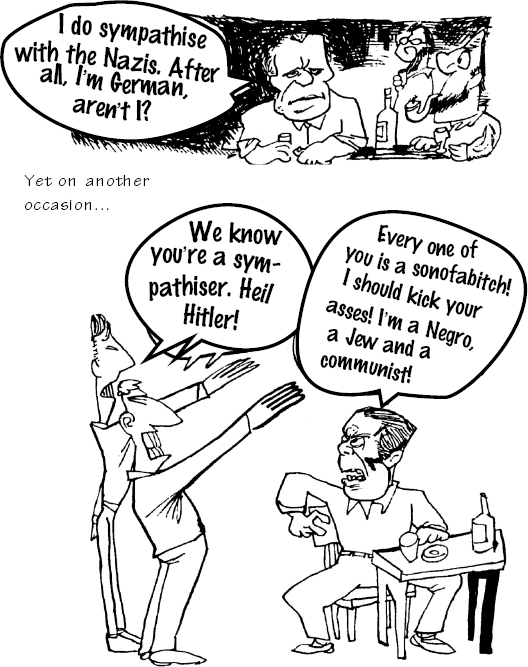

At the time, the university was full of left-wing militants, but politics were not important to Hank. Naturally, he set himself against the general tide of student thinking.

‘I used to lean slightly toward the liberal left but the crew that's involved, in spite of the ideas, are a thin & grafted-like type of human, blank-eyed and throwing words like vomit. essentially they are very lonely. the secret is really that they have not put society down but that society has put them down and so now they gather and hand-hold through 1/4 souls and play at tinkertoy games with 1/8 minds. there's nothing left to do except admit that they are slugs, worms, and they are not going to do that.’

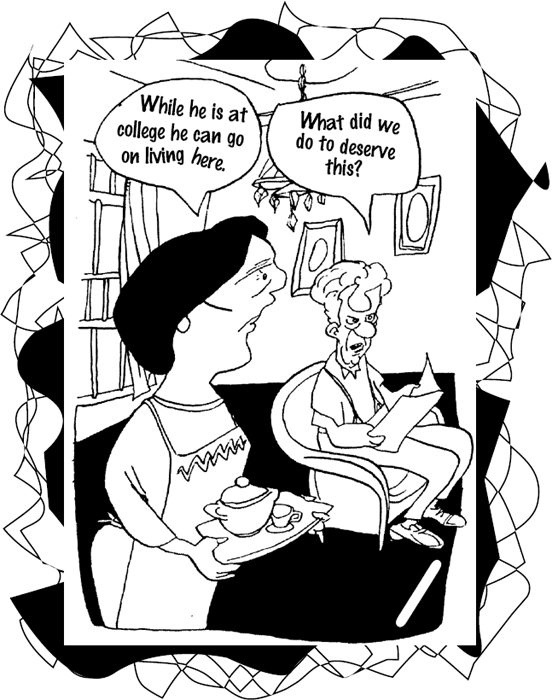

Despite continuing battles with his father, and an inhospitable home life, Bukowski had found some solace: he was writing short stories. Although he felt that he needed to embark on the course the rest of his life would take, he was anaesthetised by the relative physical comfort of his home life. He was not happy, but he had grown accustomed to it.

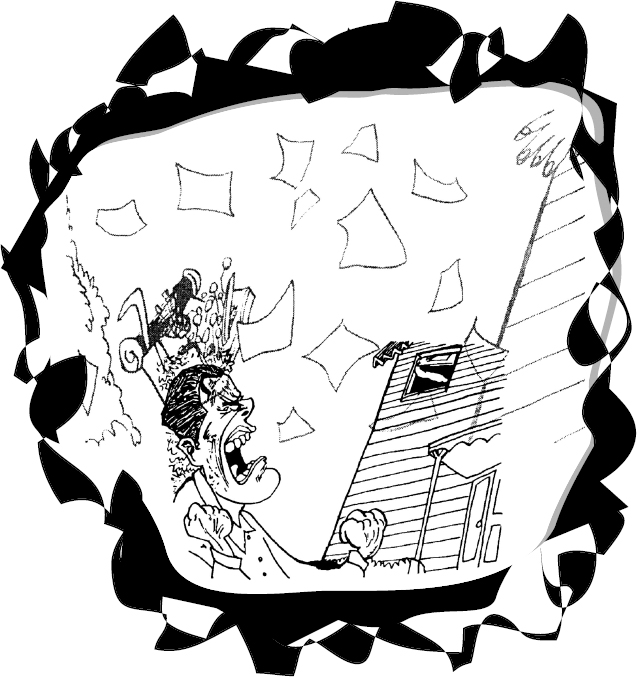

Ironically, it was Hank's early attempts at writing that would forcibly launch him into his new life. His father had found some of Hank's manuscripts in a desk drawer and was so disgusted by what he read that he threw the papers and the typewriter out of the window.

His mother told Hank what had happened. He went back to the house and, shouting from the street, challenged his father to a fight. Henry senior stayed indoors. Hank knew that the time had come to leave.

Now that he was free at last from any parental control, and with all the writing in the world ahead of him, the country itself suddenly stood on a precipice. The threat of another war was all over the newspapers, but Hank was not willing to subscribe blindly to the tide of patriotism:

‘It wasn't long before all the tall blond boys had formed The Abraham Lincoln Brigade—to hold off the hordes of fascism in Spain. And then had their asses shot off by trained troops. Some of them did it for adventure and a trip to Spain but they still got their asses shot off. I liked my ass.’

From now on, for the next thirty years, until the publication of Post Office, Bukowski would choose to escape from the mainstream, hiding on the dark side of the American dream.

In fact, most of his literary output hinges on the adventures and misadventures of his descent into hell—the hell of being poor in a society that only values the ability to make money.

In 1942 there began a period of travelling, through New Orleans, Atlanta, Fort Worth, Sacramento, Philadelphia, St Louis, San Francisco and New York, moving from job to job, fight to fight, woman to woman and one drunken binge to another

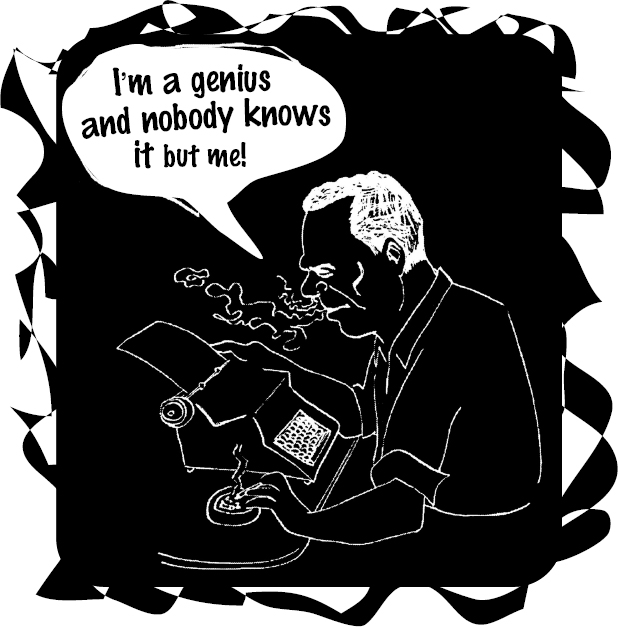

During those first years of his adult life, Bukowski cultivated a rather romantic image of himself. He felt that one day the world would come to know of his suffering. So he would accept the sacrifice; a life of deprivation was a necessary part of the story of his life. He was like a boxer in training for the toughest of fights.

Through those hard times, Hank kept on writing, in miserable guest houses and hotels. He sent his writings to magazines and reviews throughout the country. He gambled what little money he won at the races. He liked the minimalist lifestyle, having no greater dream than literary glory.

He felt like a member of the underground before the underground movement even existed. He was one of life's deviants, eccentrics, dissidents—a refugee and fugitive from Parnassus, at a time when nobody knew that any ‘counterculture’ was possible.

He was a tough character who lived from day to day, thinking only of getting enough money for his next drink and cheap meal. When he pawned his typewriter, he wrote in notebooks and jotters. But he did not get depressed; his cure was to go to the races, and he got over it.

If, when he left home, he saw himself as the hero of an action adventure, the young writer gradually realised that, in order to earn a little money, the only possible adventure was survival:

‘...fun and danger hardly put margarine on toast or fed the cat. You give up toast and end up eating the cat.’

Meanwhile, thousands of young men, filled with patriotism, were being drafted into the army. But Bukowski had, unintentionally, managed to elude the government while roaming from city to city. He was arrested in Philadelphia and spent a night in jail. However, he was declared insane by a military psychiatrist. The doctor had in his files some papers that the FBI had seized from the hotel room where Bukowski was arrested. A line from one of them read: