One

GETTING TO WEST SEATTLE

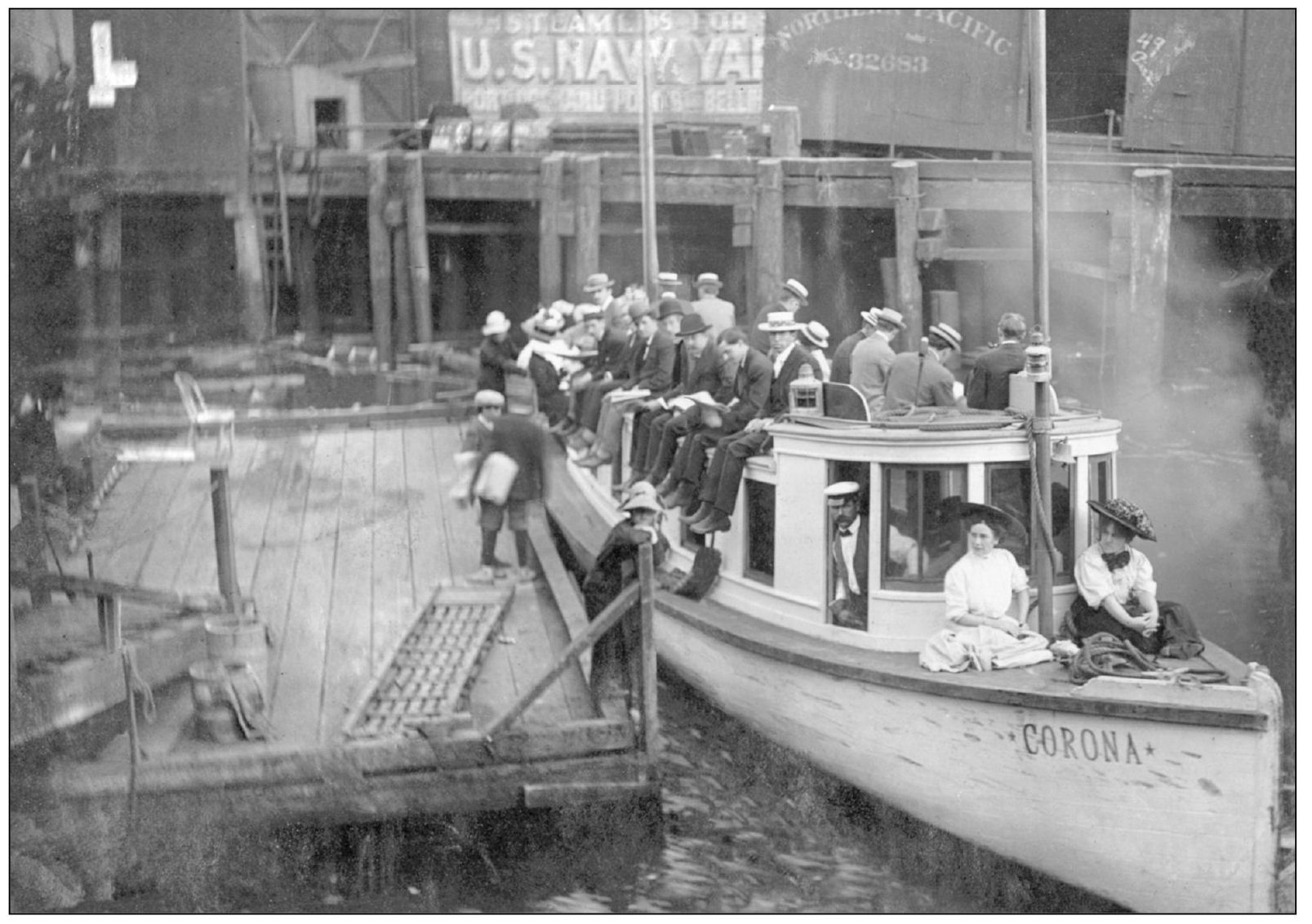

Since roads were rough or nonexistent, a vast fleet of small steamships, known collectively as the “Mosquito Fleet,” transported passengers and freight to hundreds of small docks over Puget Sound. The Mosquito Fleet ships were so nicknamed because they were small and quick, flitting from one side of the sound to the other. Their heyday of operating was 1880–1920. In 1908, the Corona readied to launch from downtown Seattle for Alki Beach with a full deck of passengers. Capt. C. C. Guntert piloted it daily, excluding Sundays. That same year, the steamship fleet transported $15.6 million in cargo and two million passengers over Puget Sound waters.

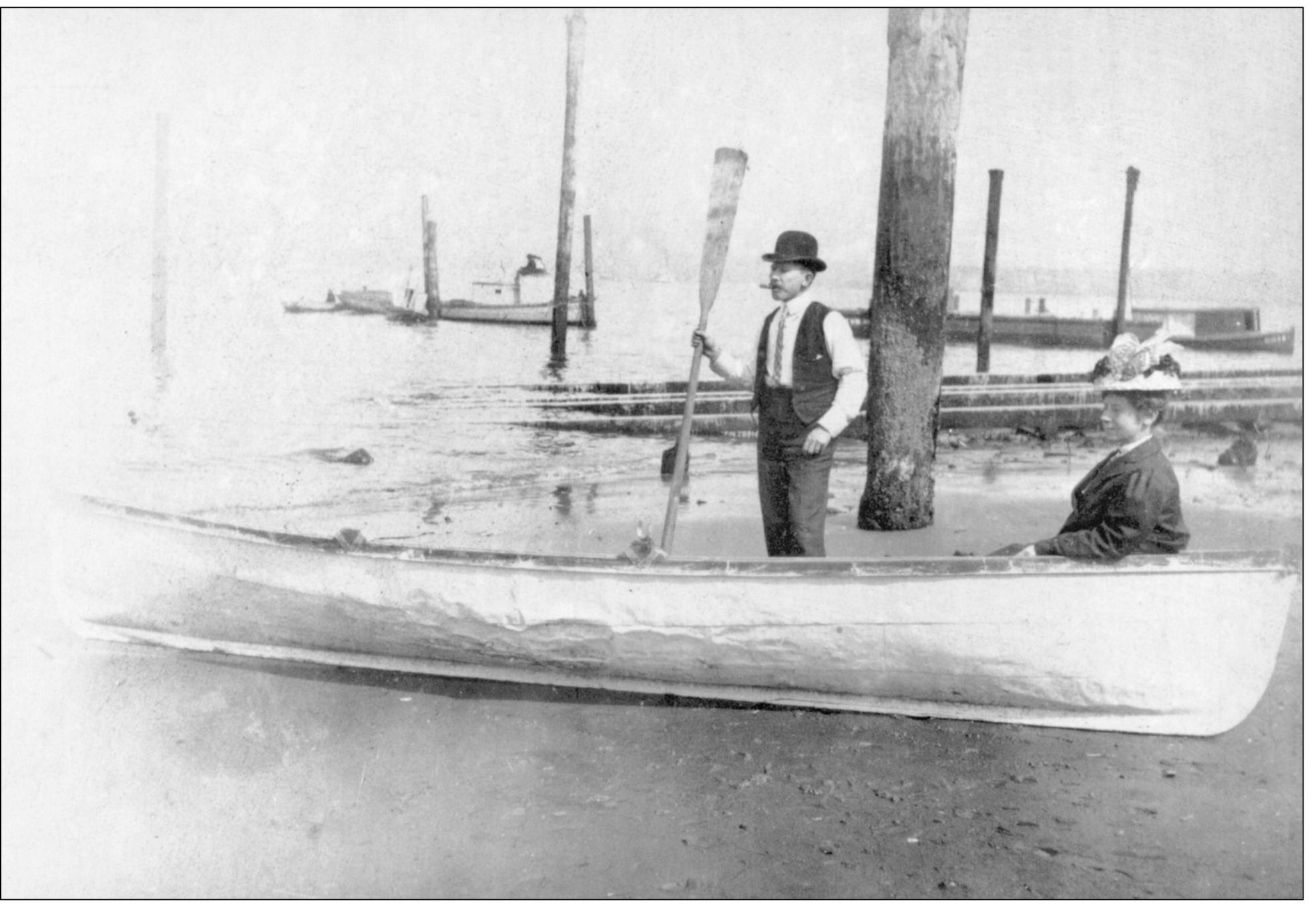

Ida and Claude Outland are pictured in their boat at low tide near Bonair Drive SW in 1909. The ramp in the background was used for launching larger vessels after repairs. Many waterfront residents had their own small boats for fishing and transportation.

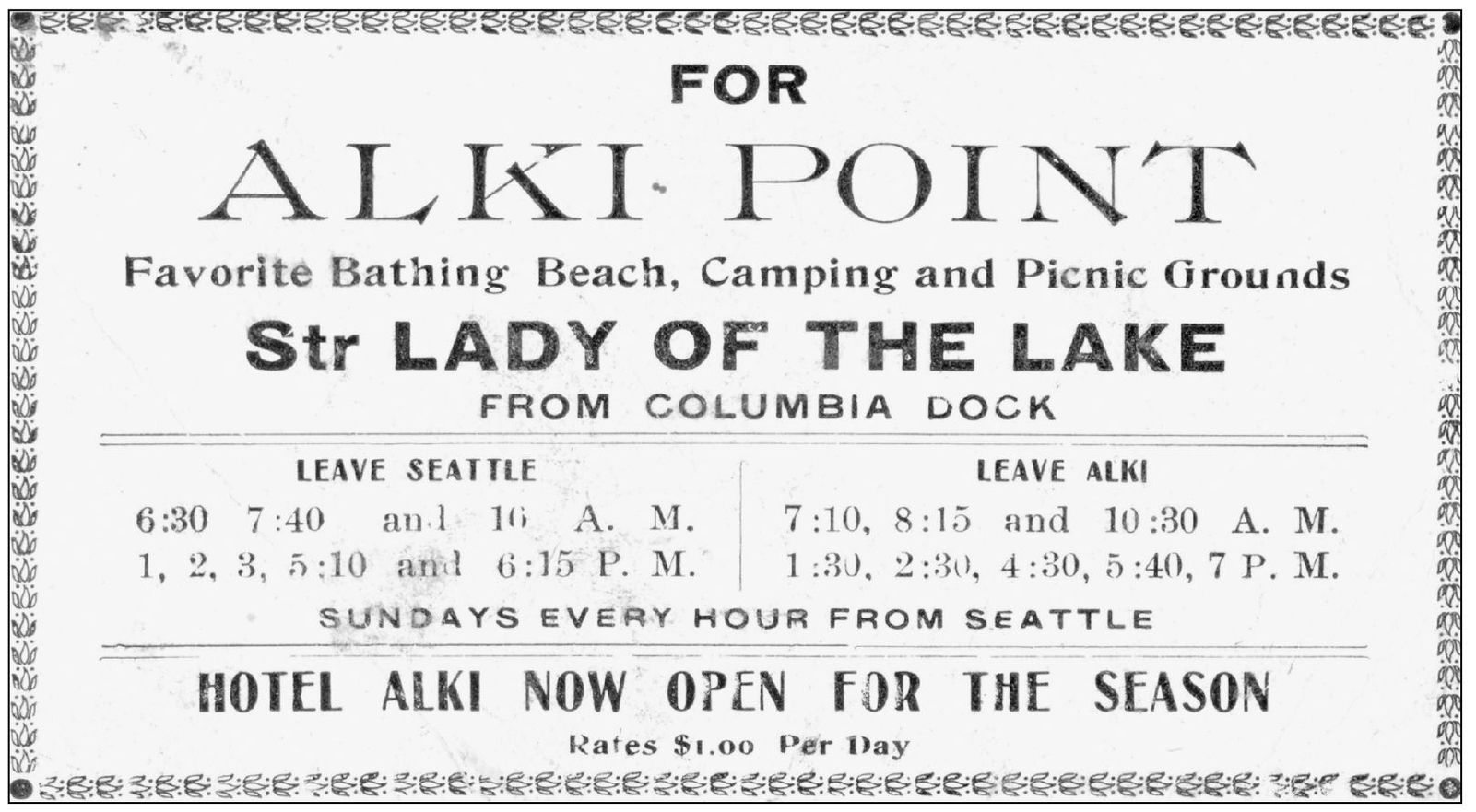

Around 1900, the steamship Lady of the Lake was in business competition with the City of Seattle ferry and mysteriously burned during a rate war for Seattle-to-West Seattle run passengers. The ticket advertises lodging at the Alki Hotel for $1 a day next to the “favorite bathing beach, camping, and picnic grounds.”

On the Alki boardwalk, finely dressed picnickers and beach strollers enjoy the view as the stern wheeler Fairhaven arrives at one of the docks on Alki Beach around 1900. The dock is located near the present-day Birthplace of Seattle monument. Mosquito Fleet steamers were a very common method for delivering passengers and cargo to West Seattle. The 130-foot-long Fairhaven was built in Tacoma in 1889 and served until its demise in 1918.

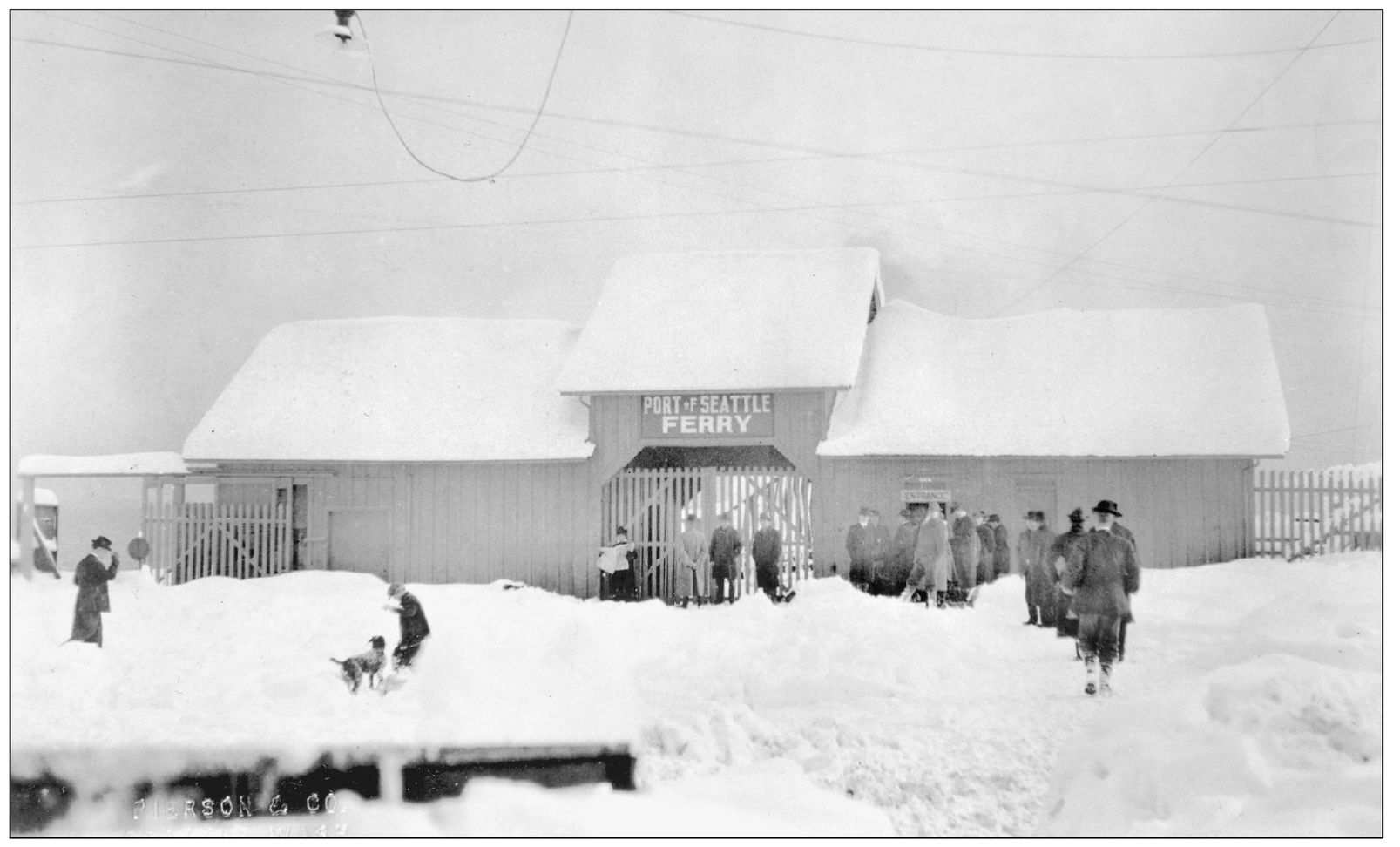

The West Seattle ferry terminal on Railroad Avenue (now Harbor Avenue SW) is shown around 1915. Ferry travel was advertised in the Westside Press (the precursor to the West Seattle Herald) as “more convenient and safer than by streetcar–besides it cuts the time of travel in half.” While crowds of travelers were typical during the summer months, far fewer of them opted for the ferry during the winter. The terminal was located near the present-day Don Armeni boat launch.

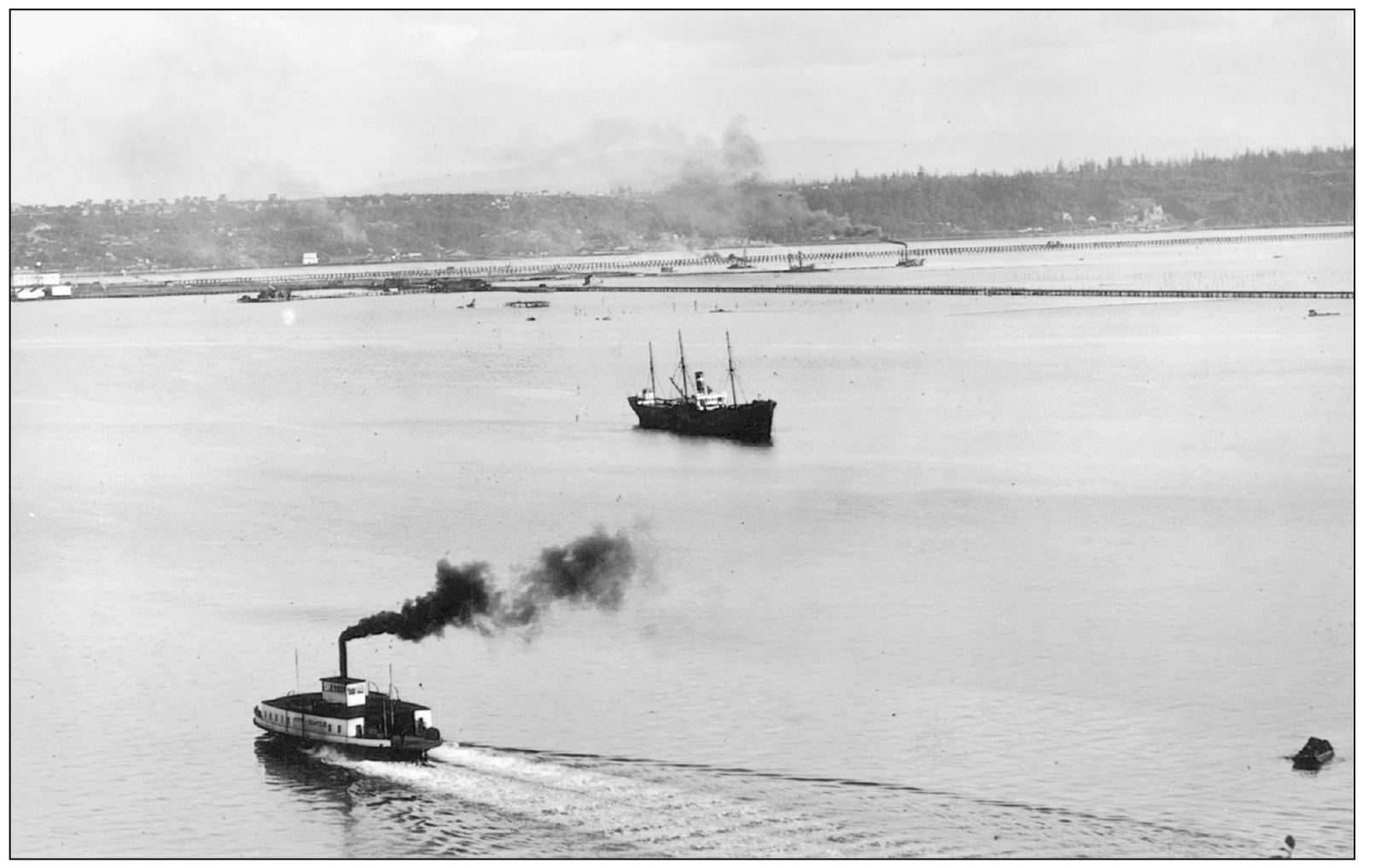

The ferry West Seattle heads across Elliott Bay to the West Seattle ferry terminal around 1910. Replacing the City of Seattle on the West Seattle-Marion Street run in 1907, the West Seattle was lauded as the largest and finest ferry north of San Francisco. A 145-foot-long steam-powered side-wheeler, she remained in service until 1920.

The City of Seattle heads east toward the Marion Street Pier in downtown Seattle in 1901. Ferry service between West Seattle and downtown Seattle began on December 24, 1888, with a fare of 15¢ and a crossing time of eight minutes. Note that the tide flats of the Duwamish River extend all the way to the base of Beacon Hill and that Harbor Island does not yet exist.

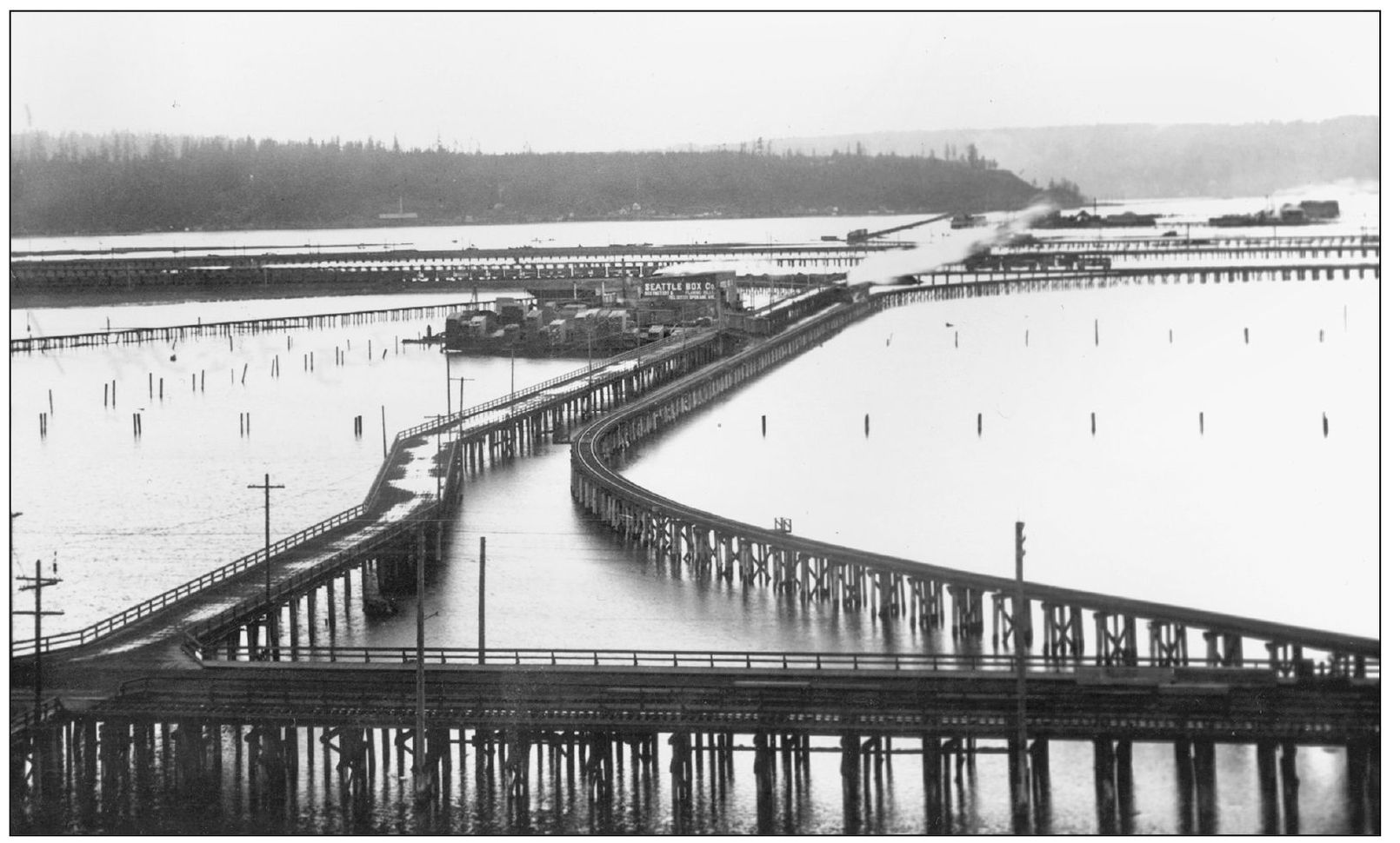

This view from Beacon Hill looks east toward Pigeon Point and West Seattle by train trestle. In 1902, Spokane Avenue led to the Seattle Box Factory and planing mills built over the tidal flats of the Duwamish River. Before Harbor Island was created and the flats filled, all of this area was underwater at high tide. The current West Seattle bridge and elevated freeway carries traffic in almost the same location.

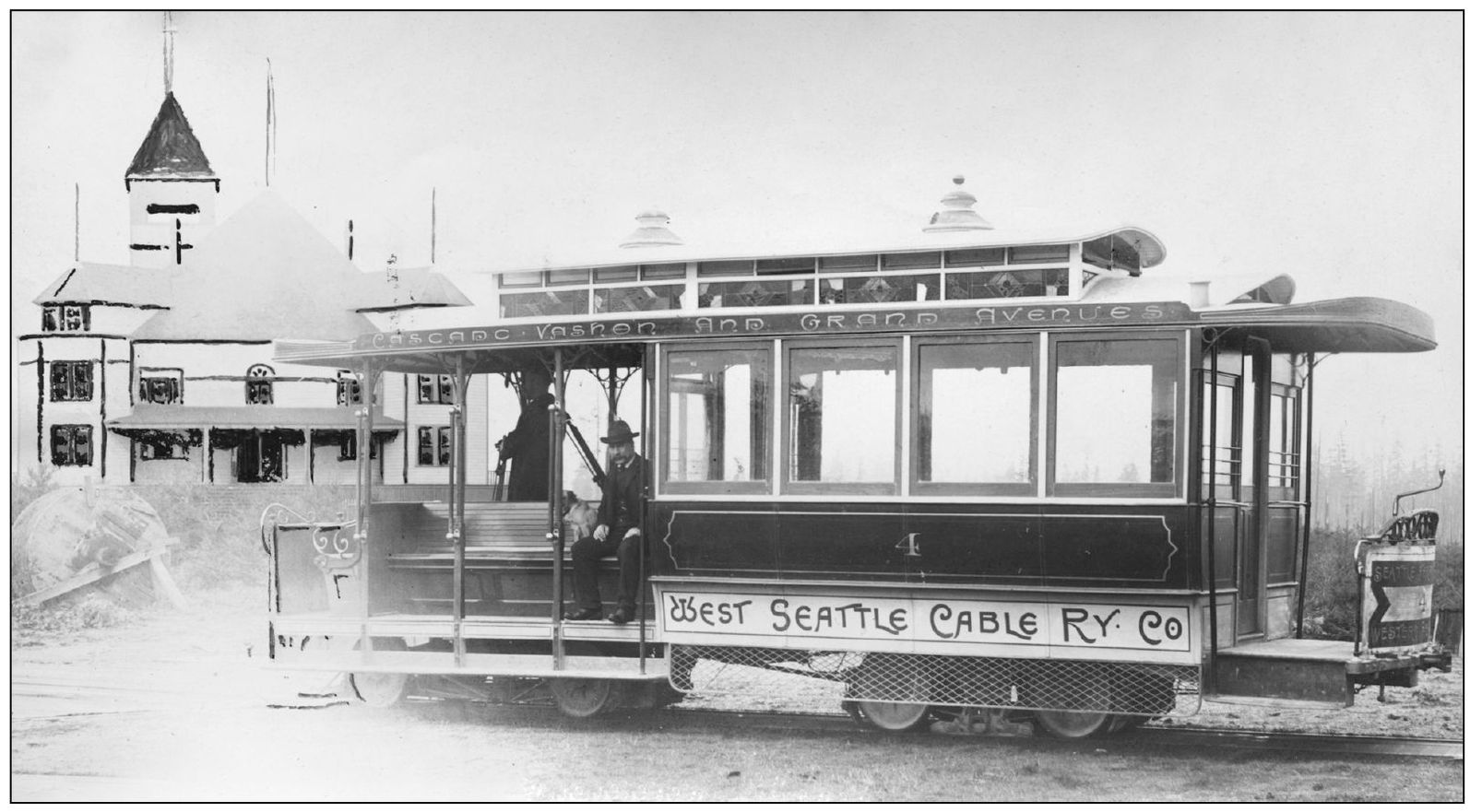

The West Seattle Land and Improvement Company started the West Seattle Cable Railway line, shown here in the Admiral District, about 1895, to augment the ferry service they founded in 1888. The intent was to promote property sales and growth in West Seattle. The cars would descend Grand Avenue (now Ferry Avenue) to the ferry dock. Financial setbacks closed the line in 1897. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 66239.)

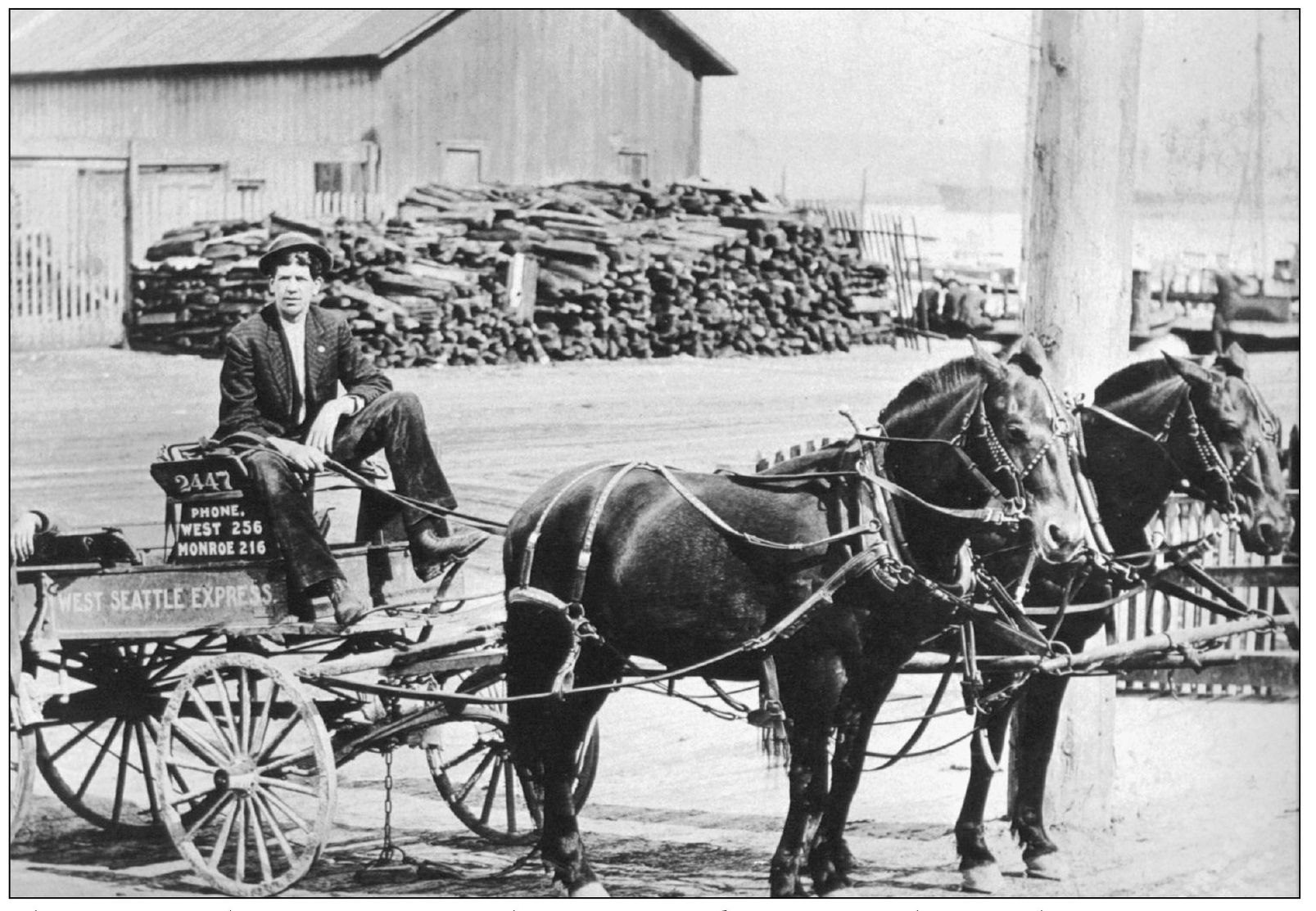

The West Seattle Express waits for the City of Seattle ferry around 1904. The proprietors were Darryl and Erik Mellencamp, shown with their horses Diane and Heidi. Delivery services like the West Seattle Express were vital to Duwamish Peninsula residents unable to carry oversize items purchased from downtown businesses.

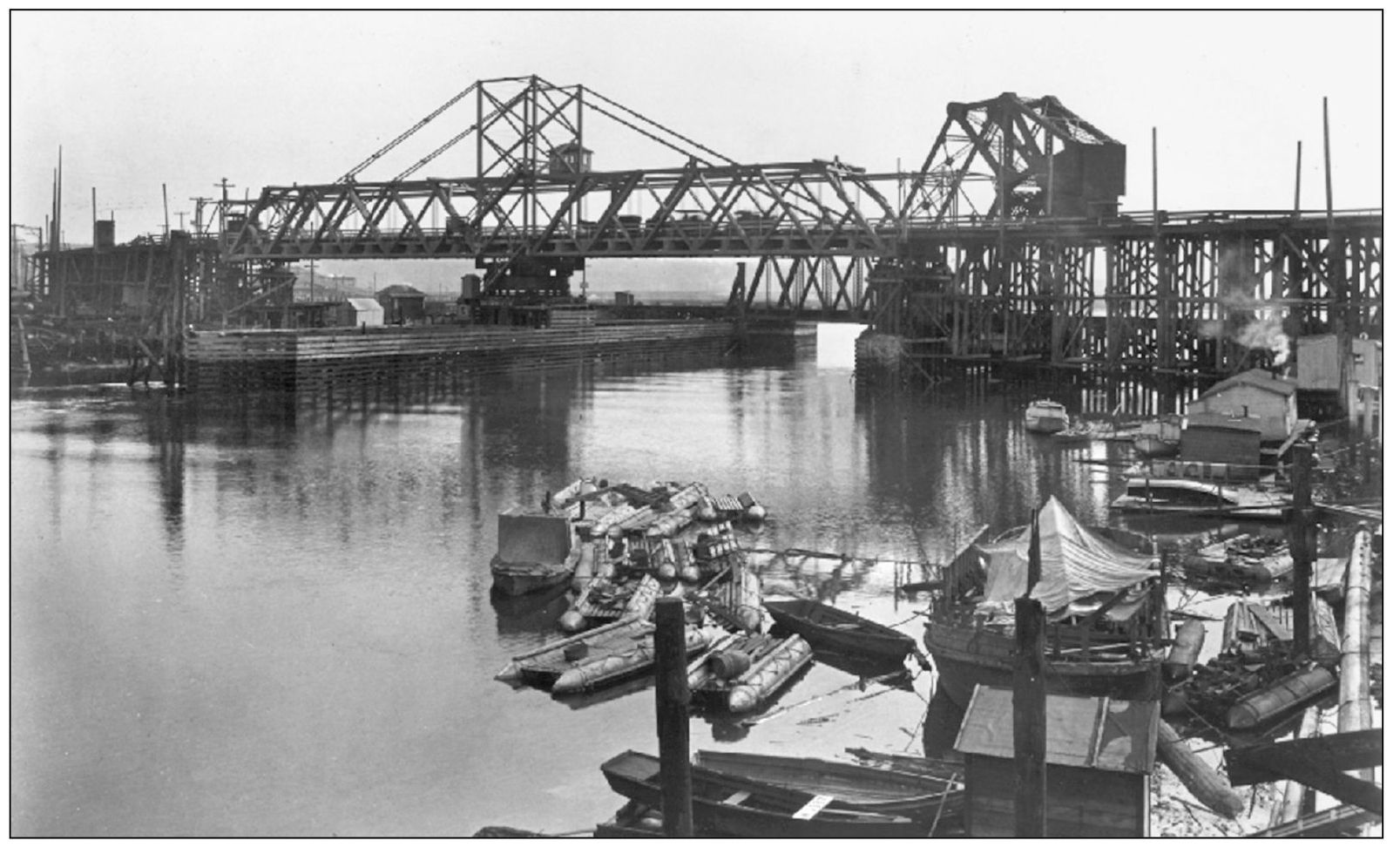

With a higher clearance of 28 feet, the new 1917 Spokane Street swing bridge replaced a temporary bridge over the Duwamish River. Per the 1913 City Engineers Annual Report, the 1910 low bridge was “constantly making traffic over Spokane Avenue more dangerous and subject to greater delays and interference” because it opened for all marine traffic. Swing bridges open horizontally as opposed to Seattle’s more common bascule bridges that rise.

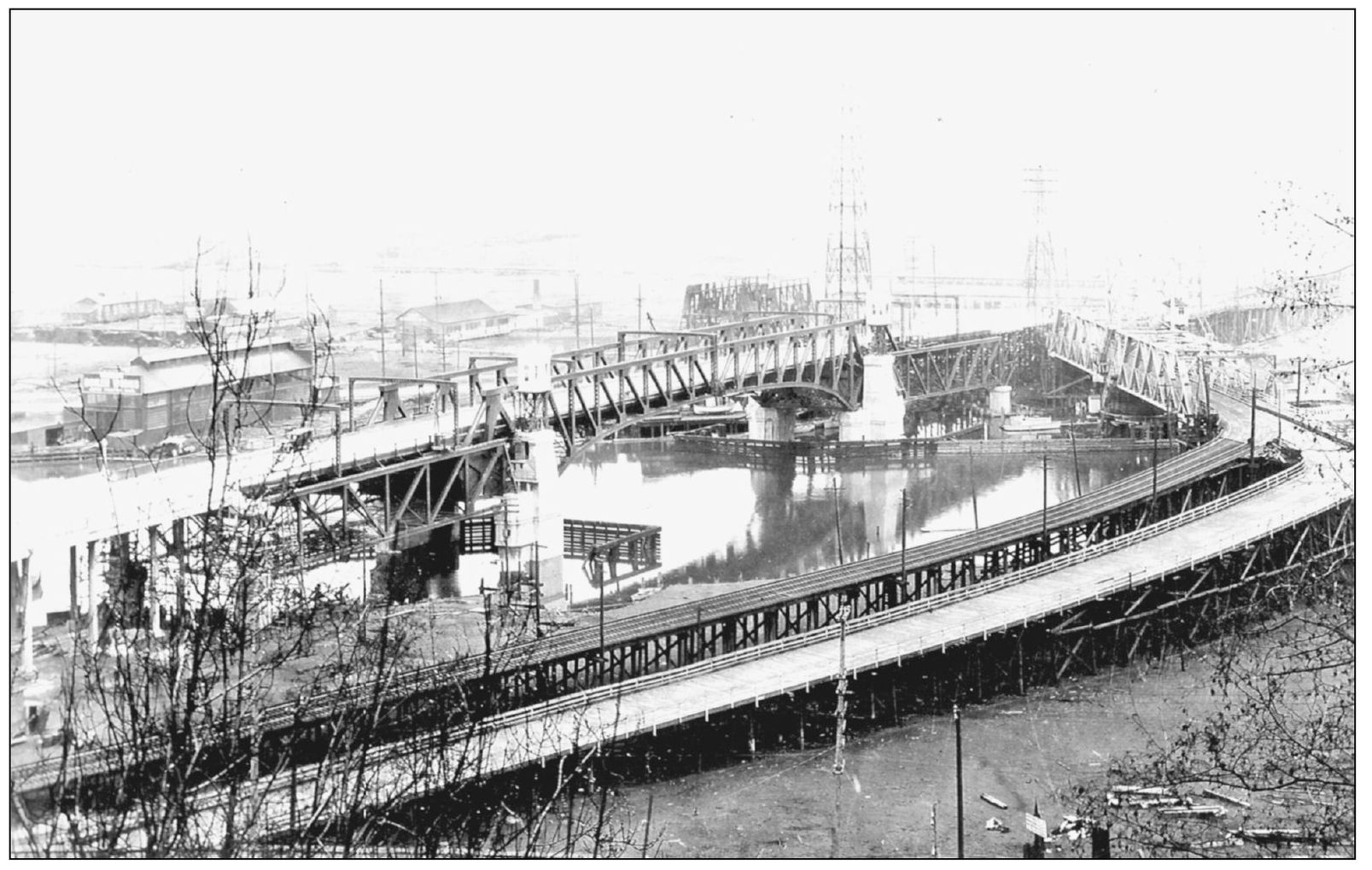

In October 1925, the West Seattle Herald stated, “The completion of the new (bascule) bridge has removed some of the greatest transportation difficulties, and no residence district in greater Seattle can surpass this district in any of the features which make living enjoyable.” All streetcar traffic was diverted to the old swing bridge on the right.

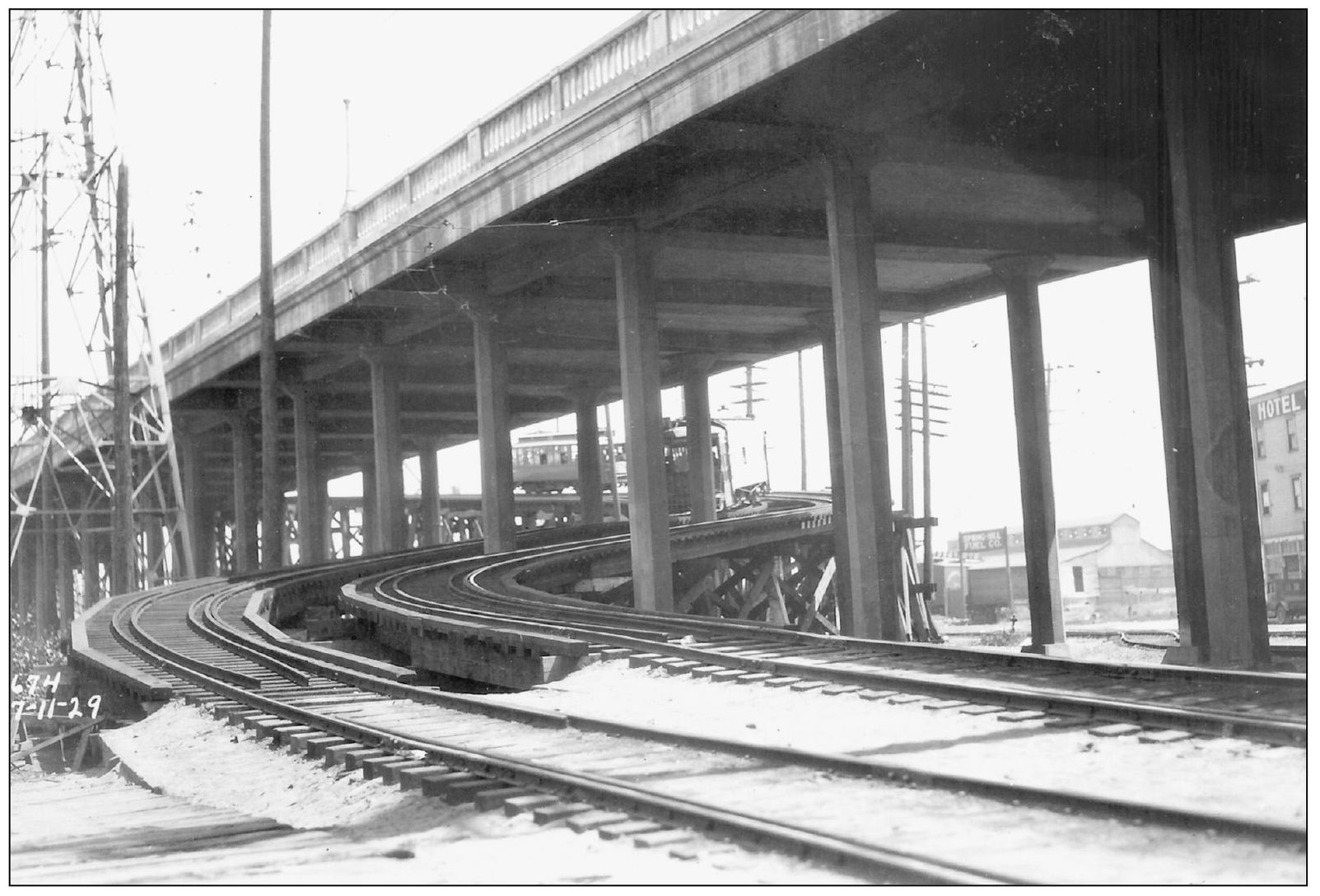

The temporary “shoo-fly” trestle was erected to route streetcars to the first Spokane Street bascule bridge in July 1929. The old 1917 vintage swing bridge had been condemned because of extensive teredo mollusk damage to the structure in January 1928. The S-shaped trestle carried streetcars up to the first bascule bridge while the second bridge was under construction.

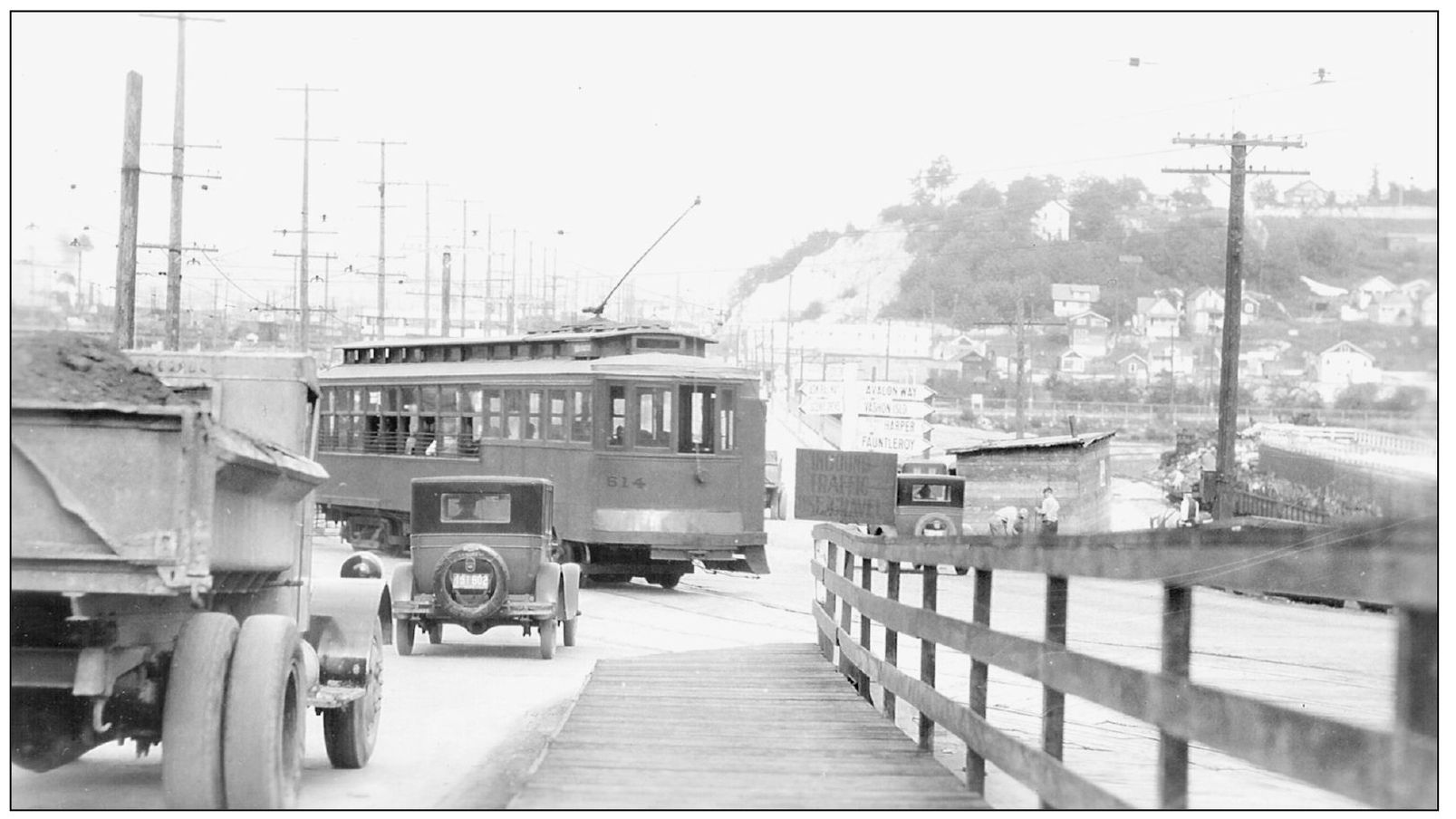

In 1929, traffic congestion at SW Admiral Way, SW Spokane Street, and SW Avalon Way was caused by streetcars, trucks, automobiles, and a few horses. This merge of three arterial streets made for many traffic challenges until improvements were made a year later in 1930. Pigeon Point is visible on the right above Youngstown. The directional signs point to Fauntleroy, Avalon Way, Harper Ferry, and Vashon Island.

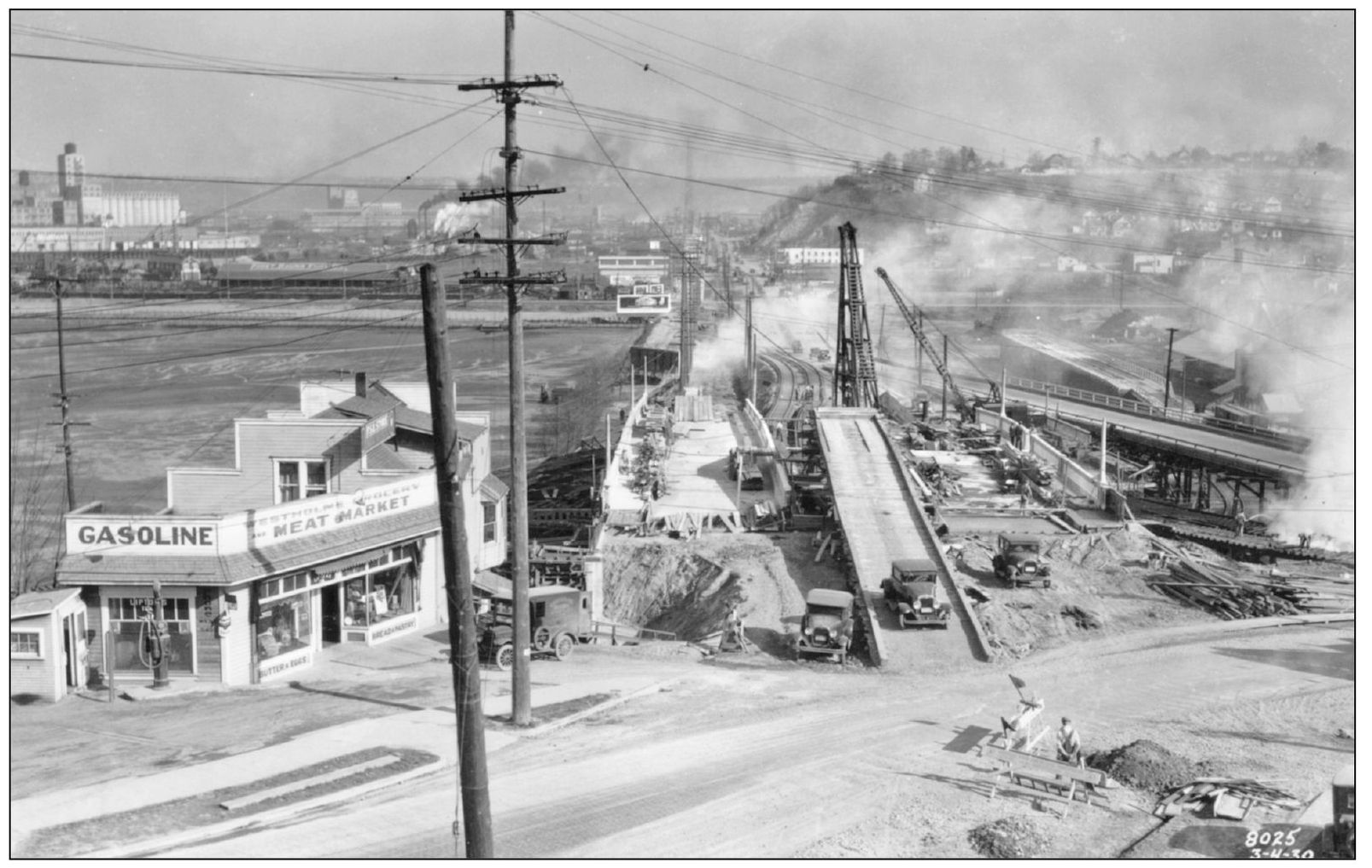

This view is looking east at construction on the concrete viaduct connecting SW Admiral Way and SW Avalon Way to SW Spokane Street on March 4, 1930. The area just north of SW Spokane Street was still tide flats. Fisher Flouring Mills is off to the left in the background, and the Pacific Coast Steel Mill is to the right.

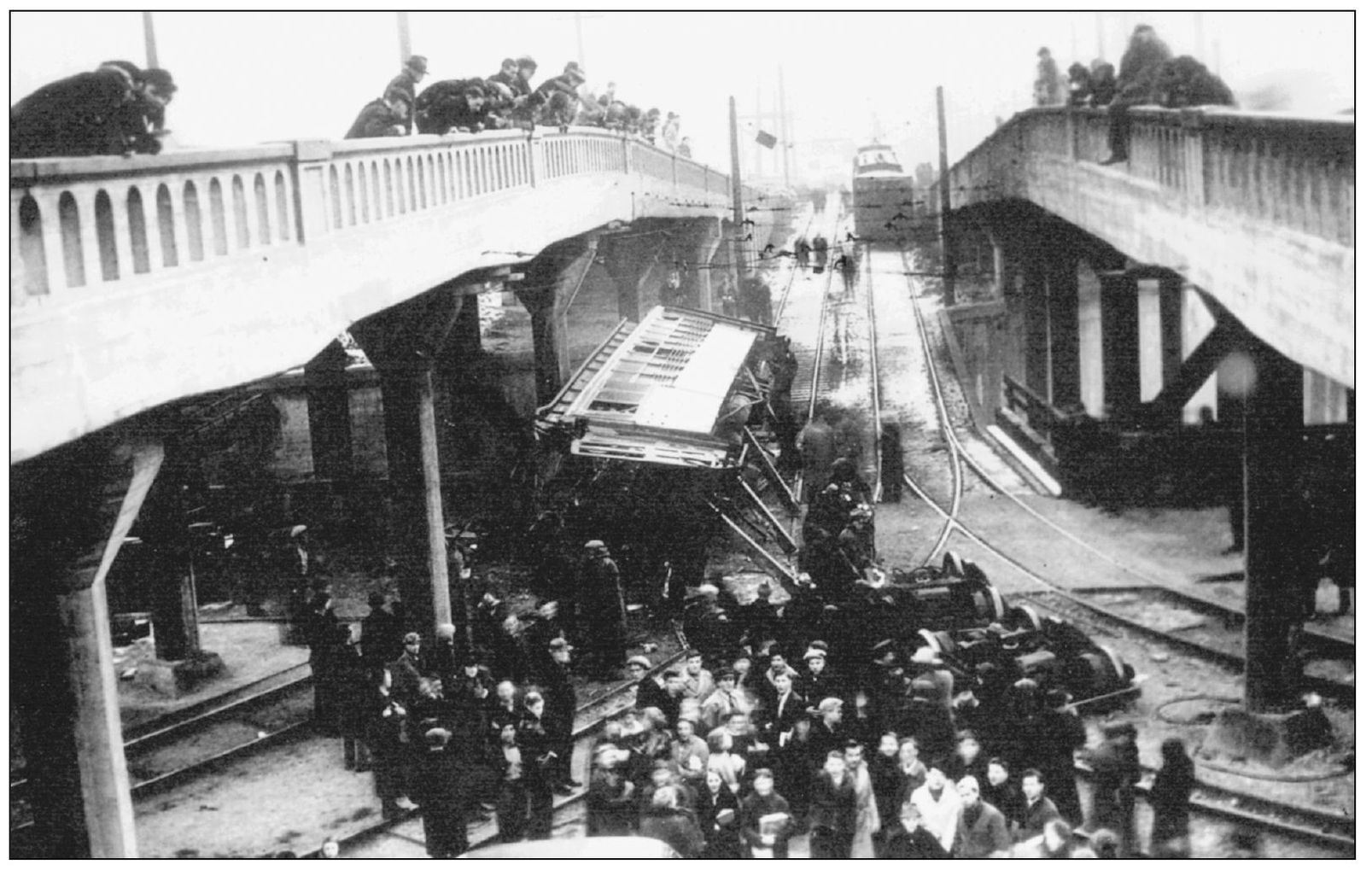

The worst streetcar accident in Seattle history occurred on January 8, 1937, when car No. 671 lost its brakes and jumped the tracks as it came down SW Avalon Way and turned east onto SW Spokane Street. The car struck a concrete pillar and was left teetering over a ravine; three passengers were killed and 59 were injured. (Courtesy MOHAI, 1986.5.12163.2.)

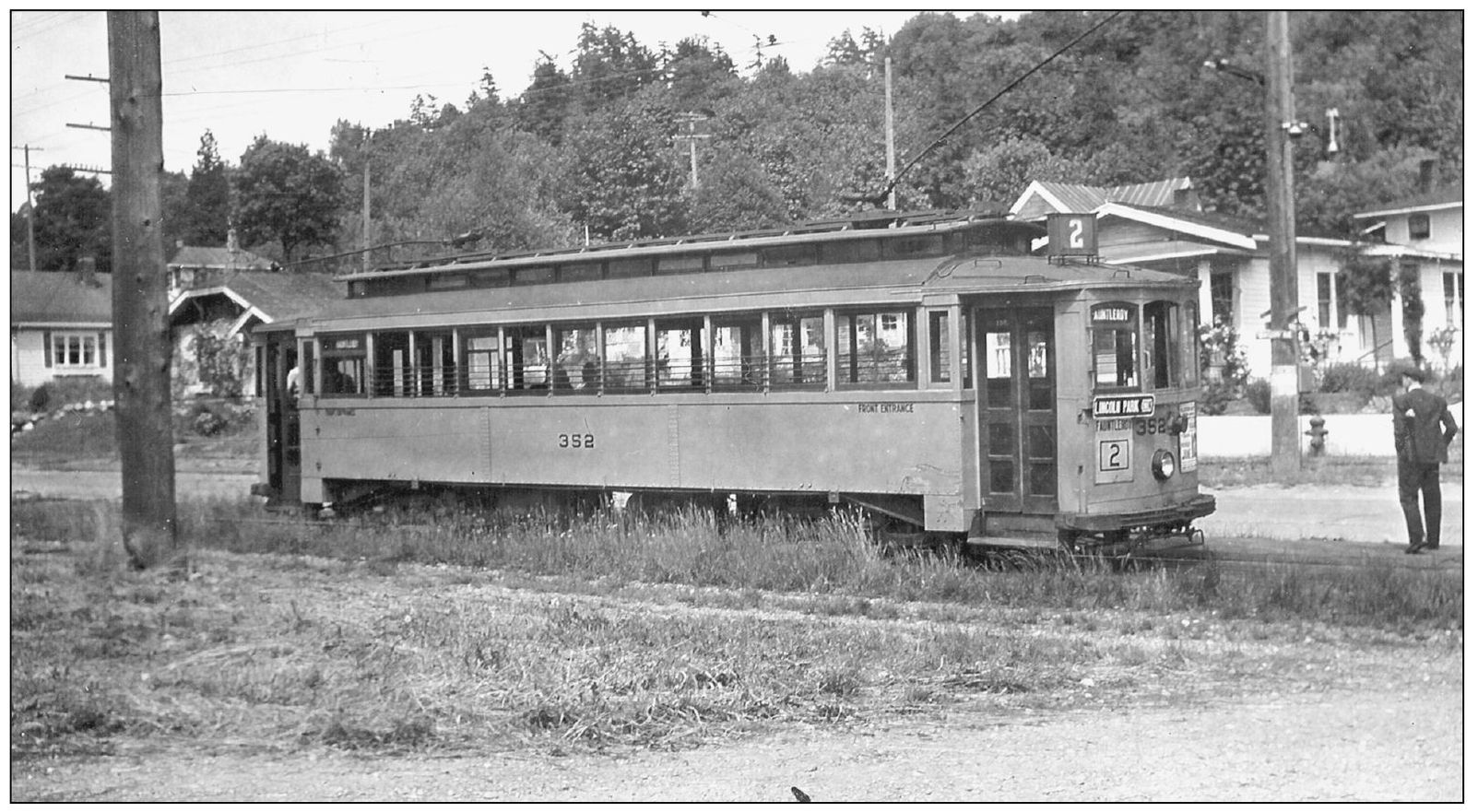

The No. 2 Fauntleroy streetcar was stopped near Lincoln Park in June 1939. The Seattle streetcar system was in poor condition by this time, due to a lack of funds and maintenance. Service to Fauntleroy began in 1907, and the last Fauntleroy streetcar ran in August 1940. From this point, the tracks continued to Endolyne in the Fauntleroy area, which was the end of the line.

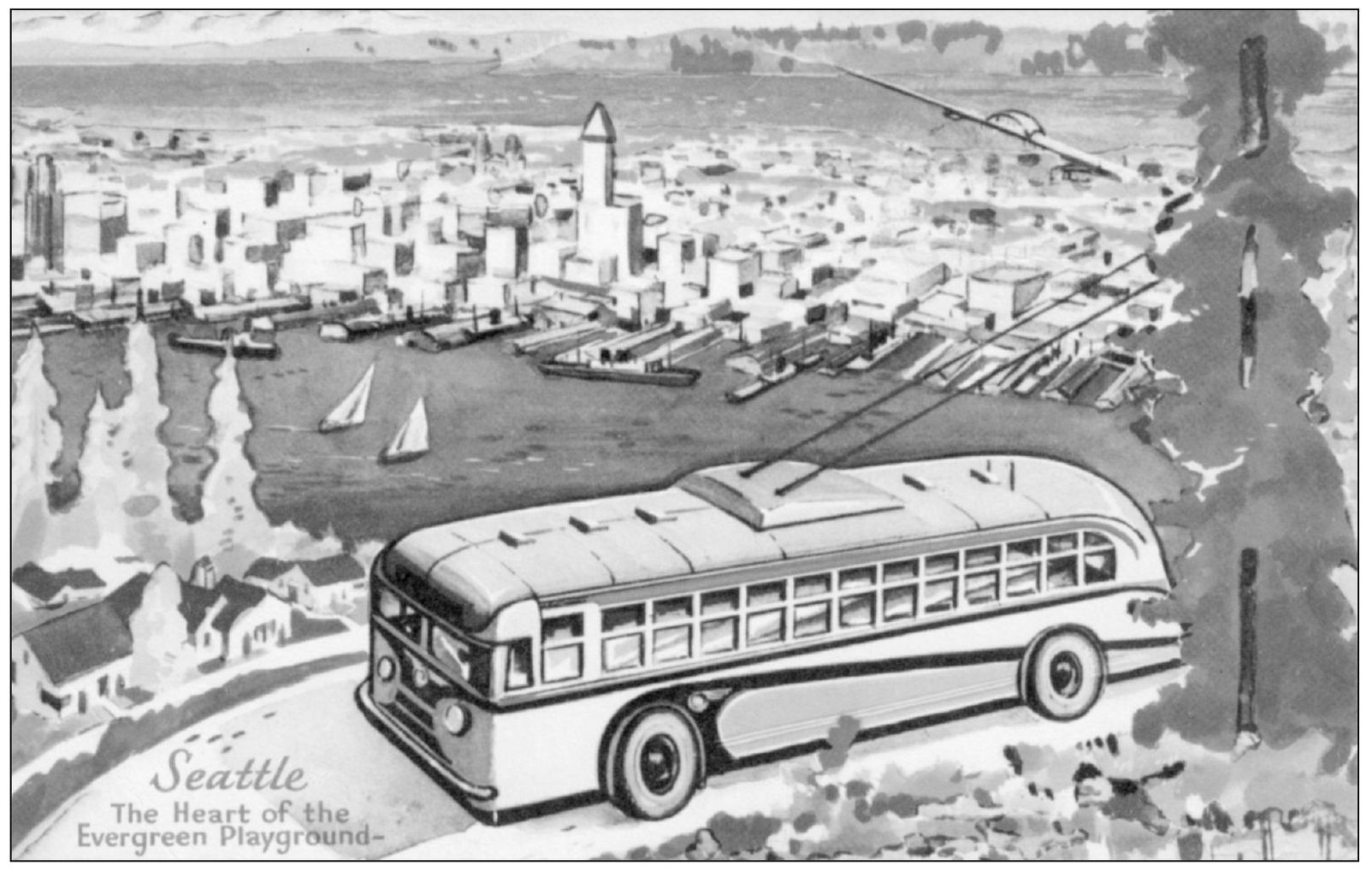

This postcard image shows a new Seattle Transit “trackless trolley” approaching the Belvedere viewpoint on SW Admiral Way in 1941. Streetcars were phased out in West Seattle in 1940, with the last one running on Alki Avenue SW in November. These electric buses were better adapted for climbing Seattle’s steep hills. The city marketed its new vehicles by distributing this card for a free transit ride to the public and tourists. Seattle ordered 235 of these buses after receiving a $10.2-million federal loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

This 1956 view is looking west on SW Spokane Street from Harbor Island. It was difficult accessing West Seattle prior to the construction of the first elevated West Seattle freeway. Often after a bridge opening, a train would cross SW Spokane Street, causing further traffic delays. Nifty’s Restaurant on the right, a Harbor Island landmark for many years, advertised “Good Food Always—Payroll Checks Cashed—We Never Close.” When the flow of traffic was moved to the elevated freeway in 1965, the once-thriving business district of Youngstown gradually disappeared. (Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, No. 54247.)

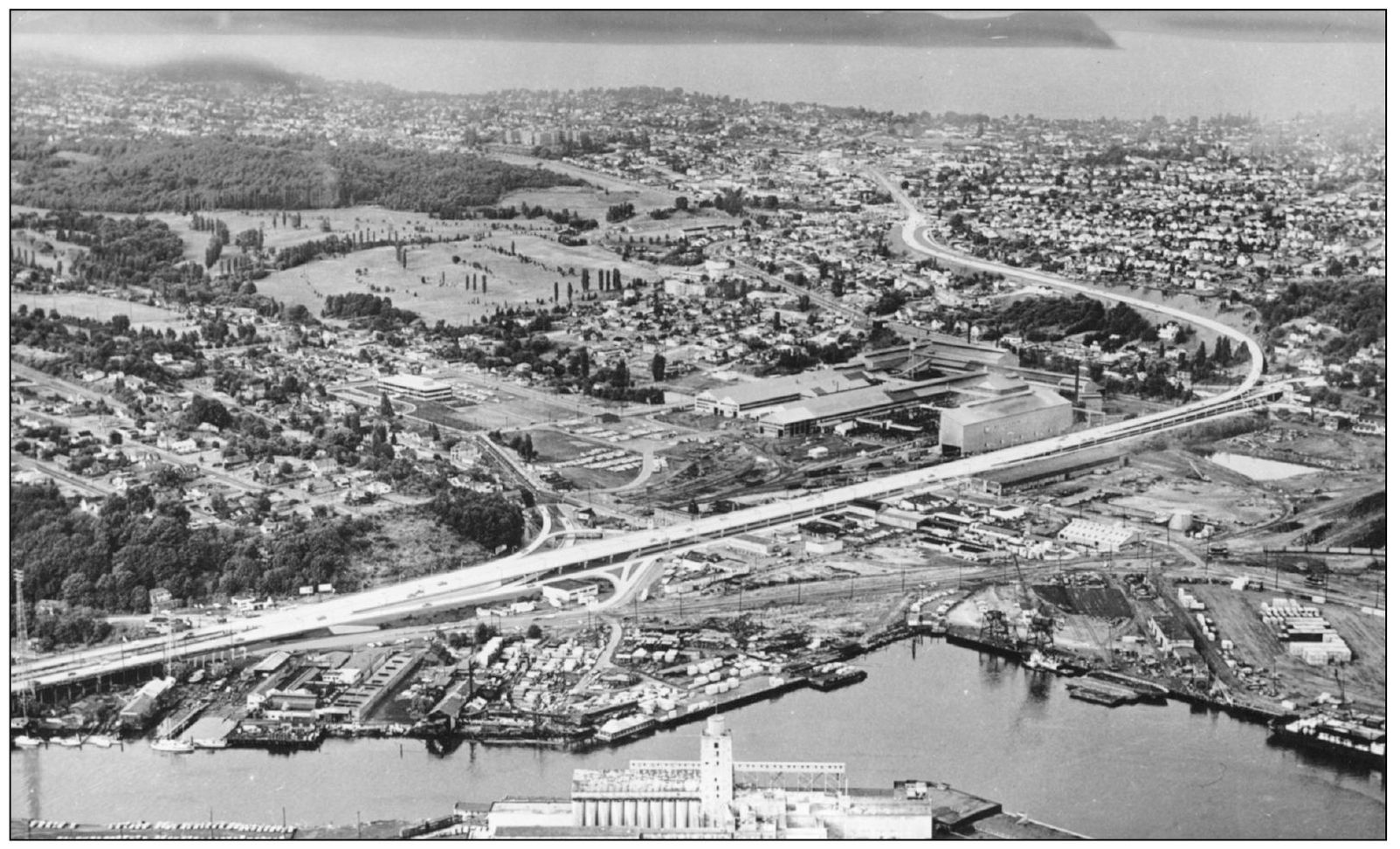

An aerial view looks southwest at the West Seattle Freeway around 1965. Originally called the Fauntleroy Expressway, it connected the two bascule bridges at West Marginal Way SW to SW Admiral Way and Harbor Avenue SW to the west, as well as Thirty-fifth Avenue SW and Fauntleroy Way SW to the south. The area remained a bottleneck. (Courtesy Frank M. Anderson.)

Holding signs that read “Vote Yes West Seattle Bridge,” enthusiastic residents staged a flotilla of rowboats in support of the West Seattle Bridge Referendum, which was approved in March 1974. New bridge proposals in the 1970s sprang from increased traffic congestion on SW Spokane Street, the second-busiest roadway in the state by 1972.

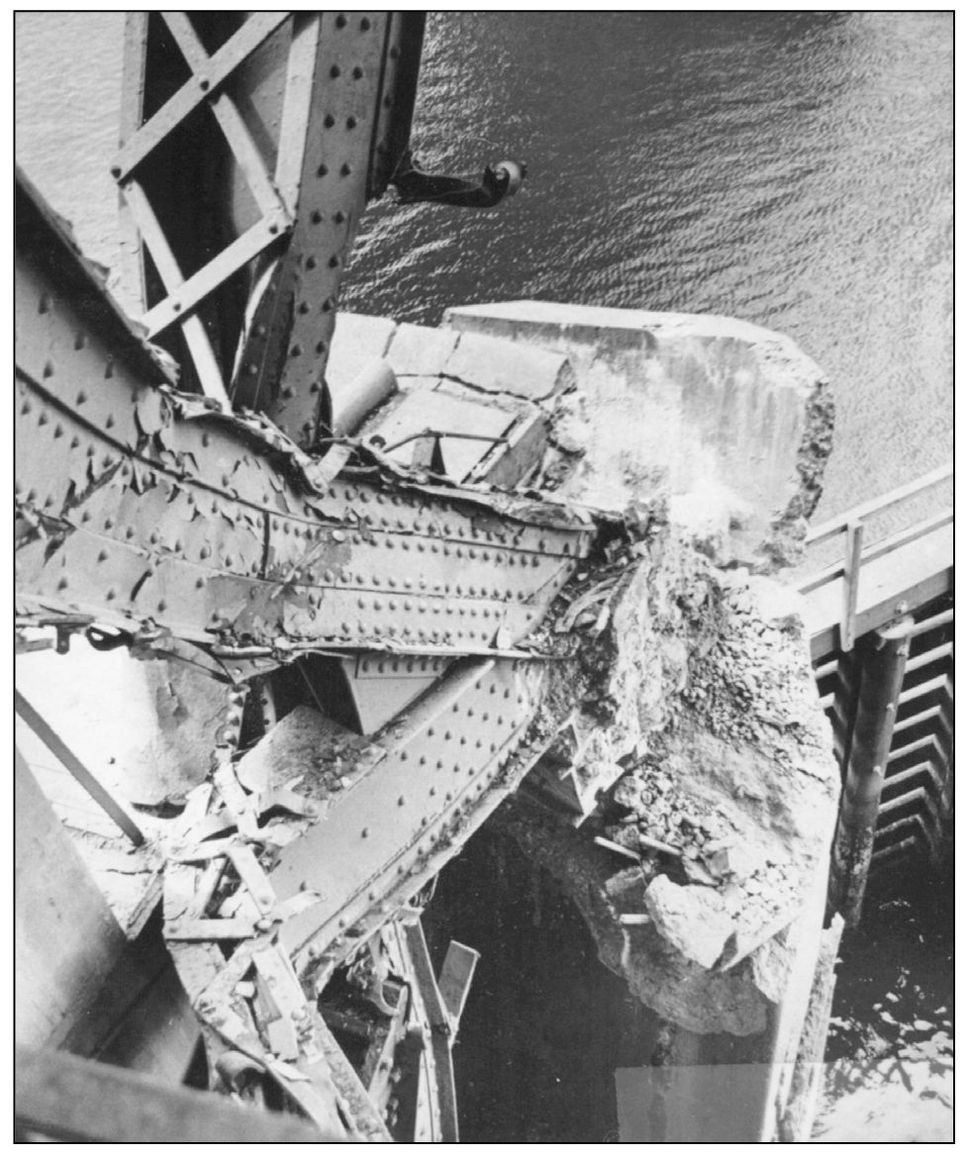

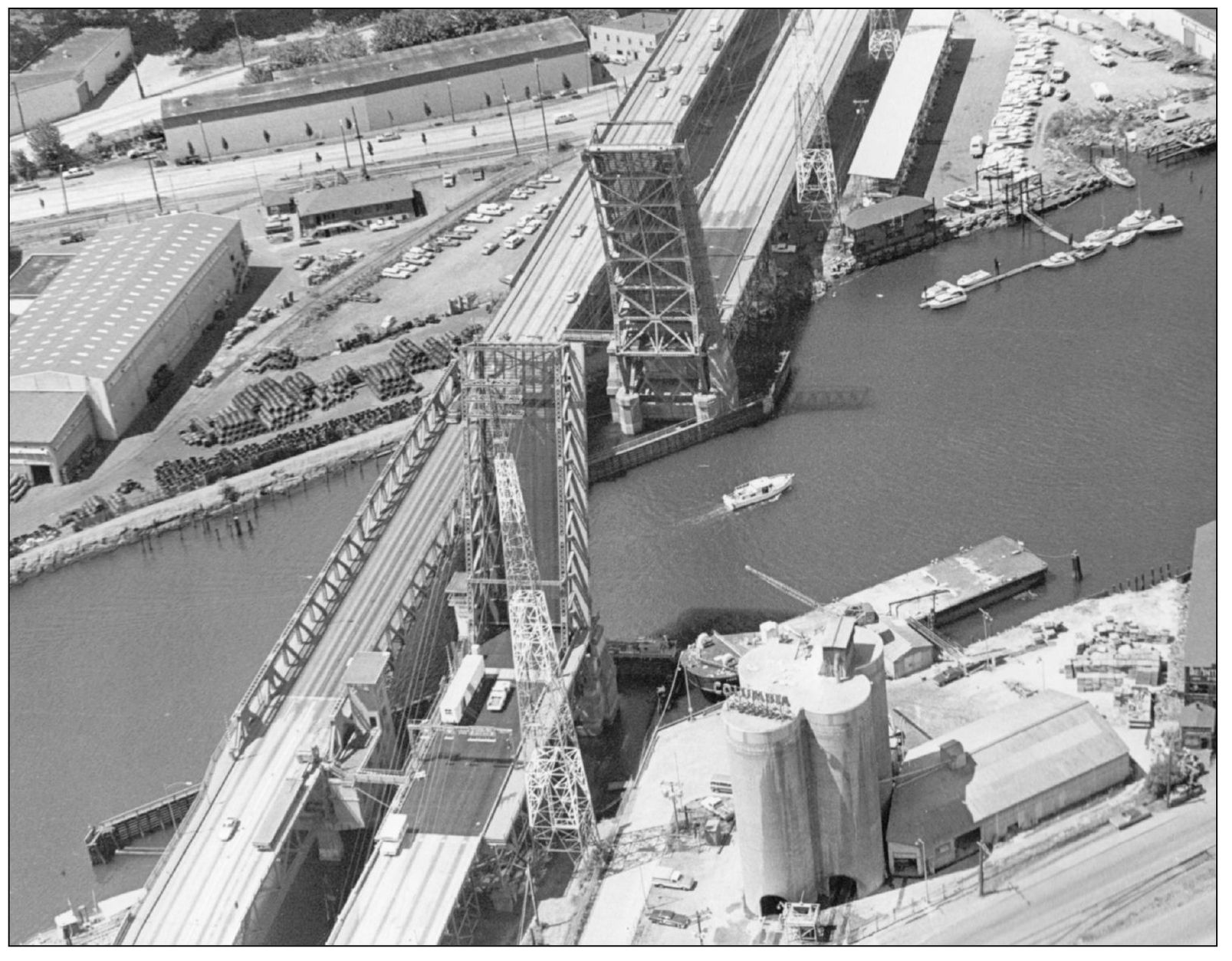

The northern span of the Spokane Street Bridge is shown stuck in the open position after the freighter Antonio Chavez struck the bridge on June 11, 1978, rendering it inoperative. Westbound traffic had to be routed over the southern span, which made traffic much worse; eight lanes were reduced to four. Duwamish Peninsula residents resigned themselves to the commuting nightmare, some with humor. A T-shirt commemorating the accident queried, “Where were you when the ship hit the span?” The damage was extensive. Structural steel that helped to bind the span to the structure was ripped out of the concrete piers, the counterweight pivot bent, and the driving gears and motors used to raise the bridge were pushed out of alignment. (Below courtesy Melvin Fredeen.)

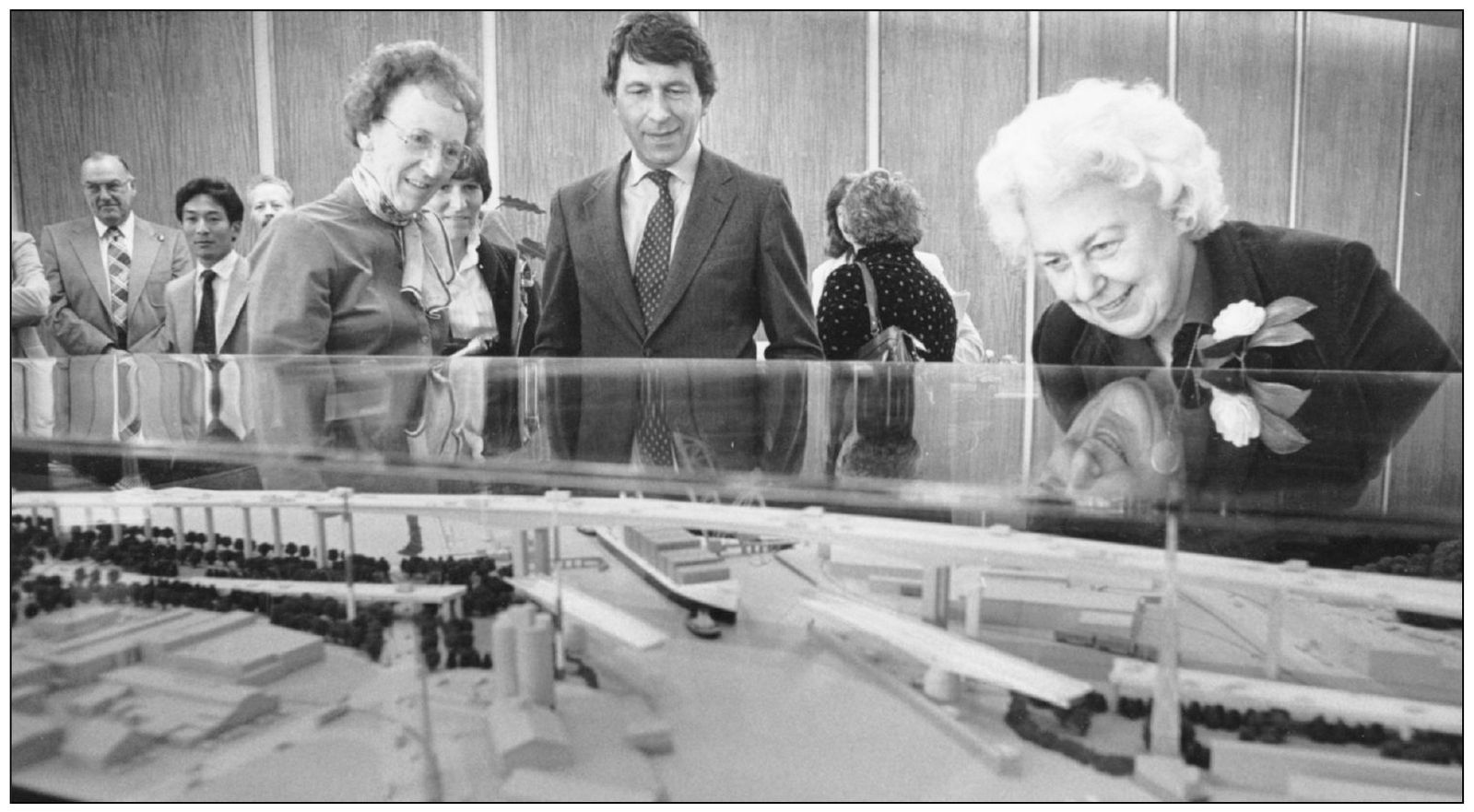

Seattle mayor Charles Royer and city council member Jeanette Williams view a scale model of the proposed high-level West Seattle Bridge around 1979. Williams chaired the transportation committee and played a key role in getting the bridge built. Various agencies raised $172 million to fund the bridge. In recognition of Williams’s efforts, the bridge was also named the Jeanette Williams Memorial Bridge in 2009.

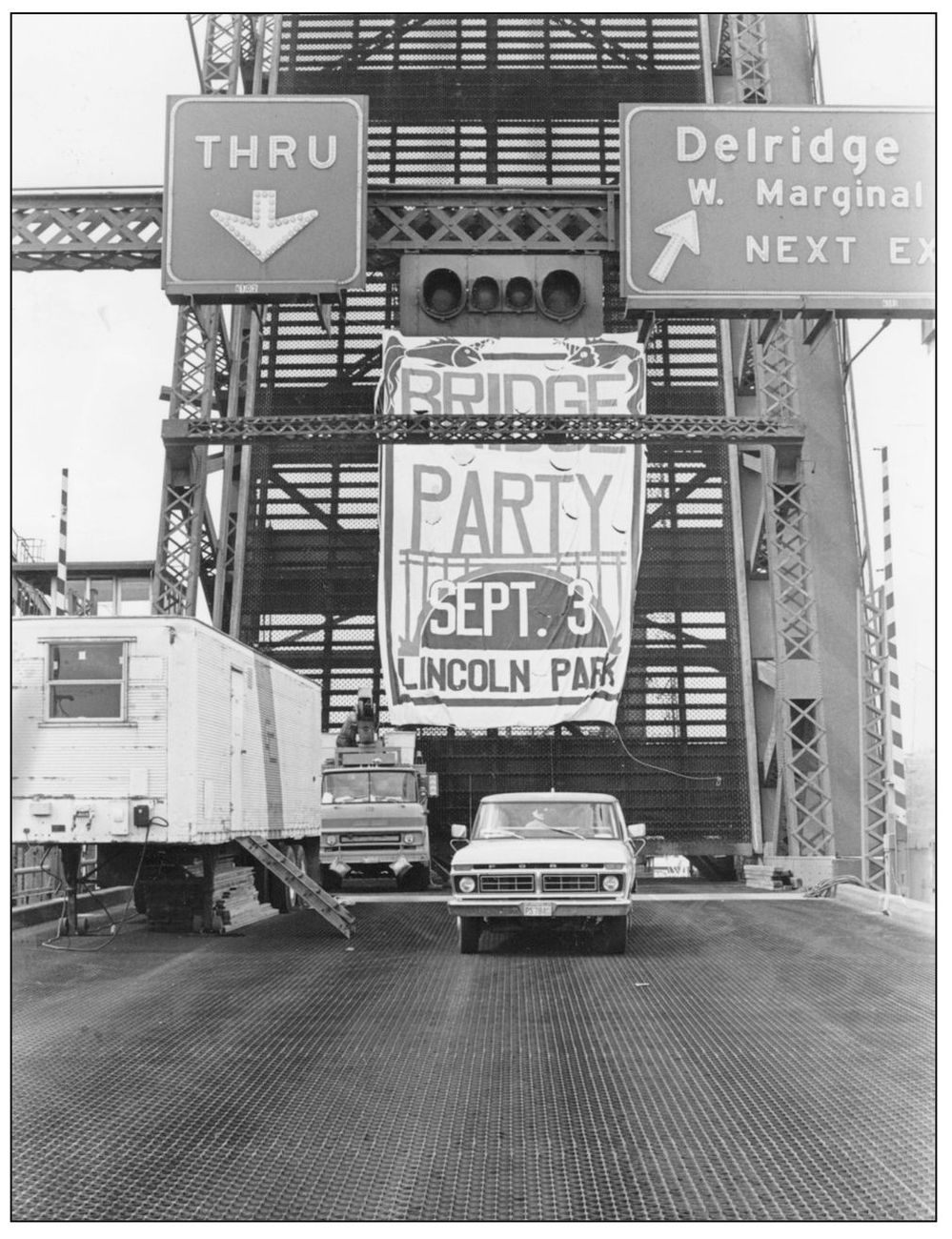

A banner on the defunct bridge advertises the “bridge party” for the new bridge held in Lincoln Park on September 3, 1978. Despite the rain, over 1,000 people showed up for the “Bashed Bridge Bash” to celebrate the funding obtained to build a new bridge. U.S. senator Warren G. Magnuson, guest of honor, was a key sponsor of the appropriations bill. Sports celebrities, live music, and the Seafair Clowns added to the bash. (Courtesy Chris Styron.)

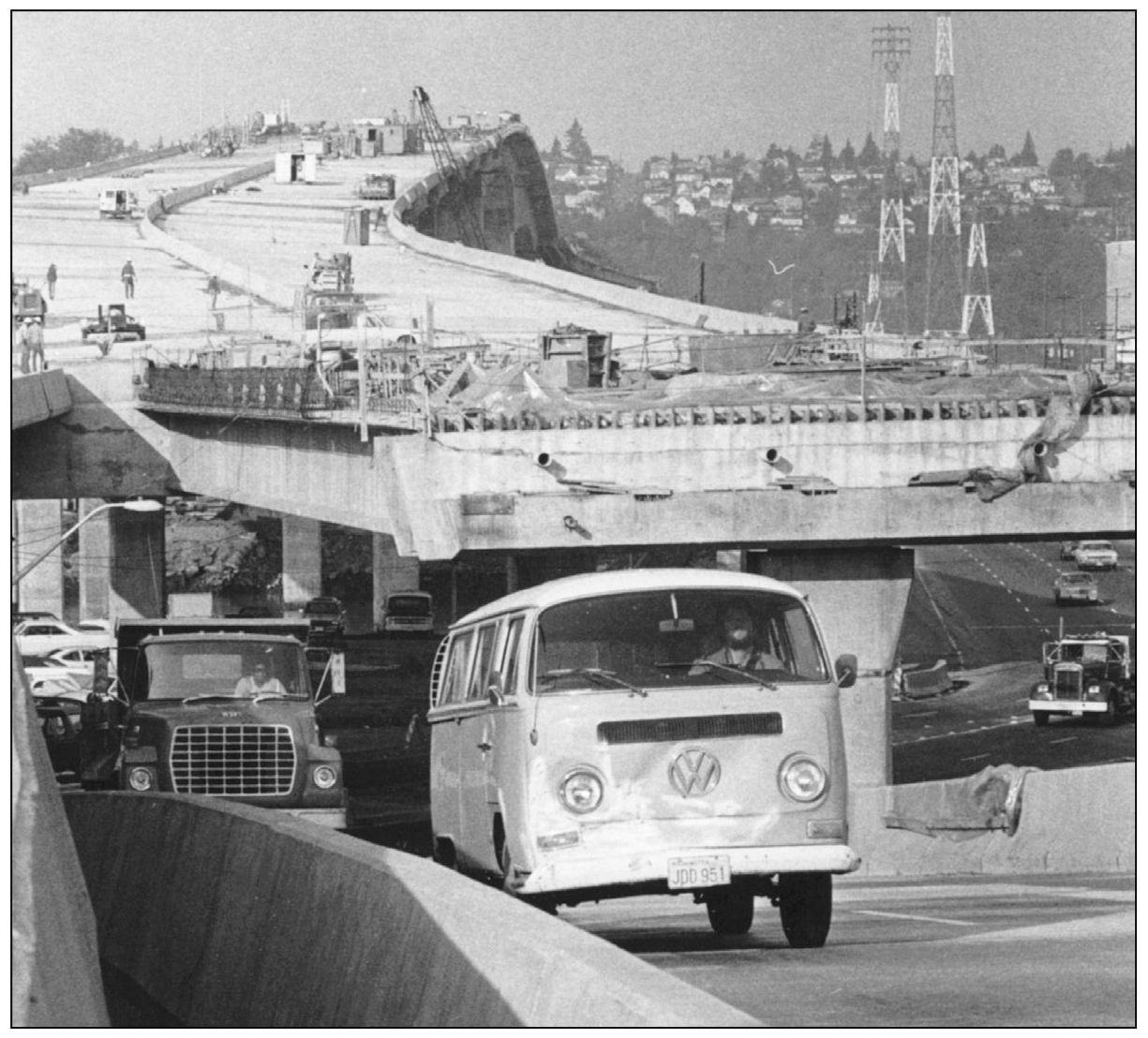

The much-anticipated West Seattle Bridge nears completion as drivers negotiate a myriad of detours and temporary routes along the corridor of the future high-level bridge. Construction began in 1980, and the two ends were joined in the middle on July 13, 1983. The four-lane bridge opened on November 10, 1983, and all eight lanes were completed in July 1984.

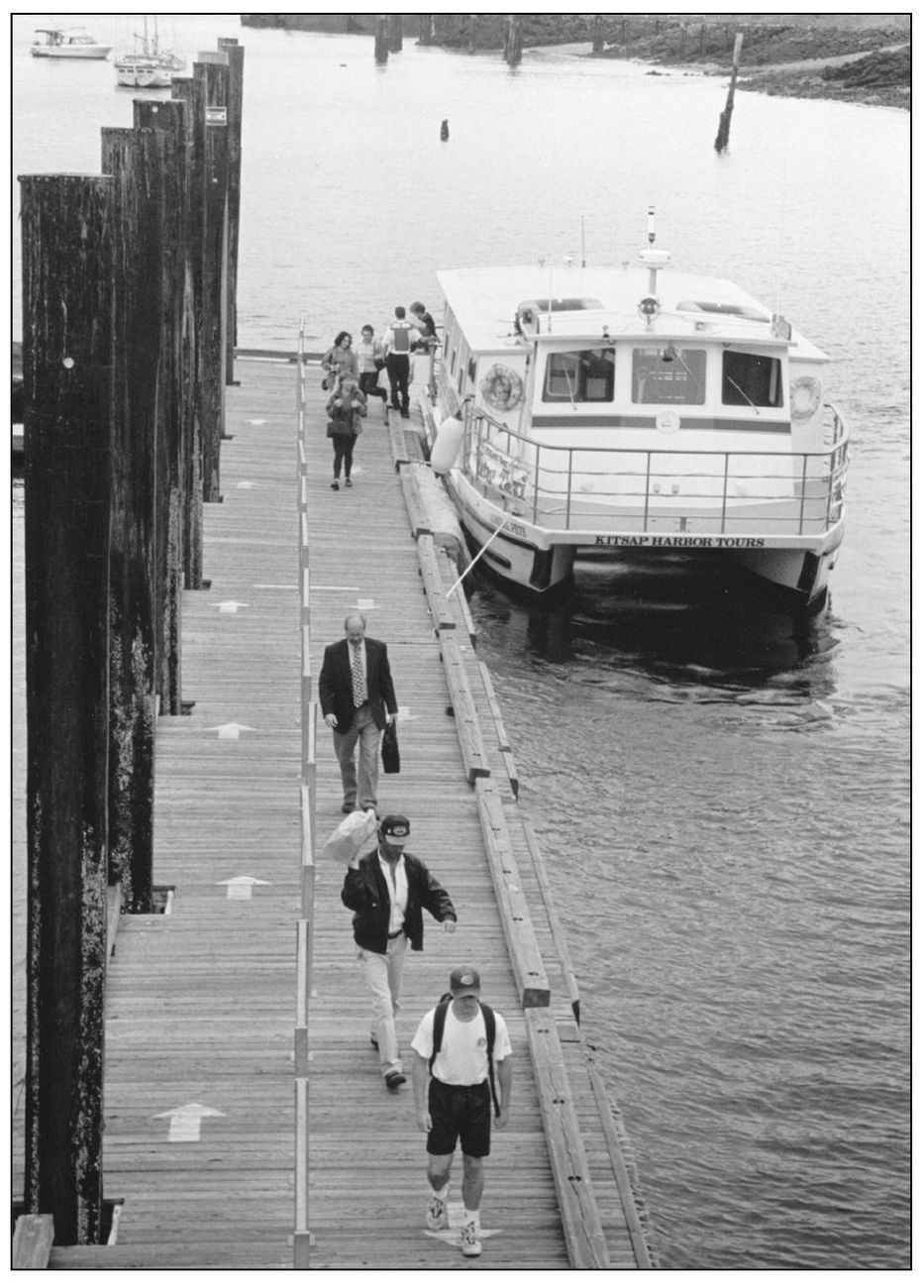

The West Seattle water taxi Admiral Pete is shown at the Seacrest Boathouse pier in August 1999. Water transportation between West Seattle and downtown Seattle was revived in 1997 on a trial basis and proved so popular that it is now in continuous operation from April through October. The crossing time is about 12 minutes. (Courtesy Bruce H. Savadow.)

This is how not to get to West Seattle. A Boeing 308 Stratoliner is recovered after it plunged into Elliott Bay off West Seattle on March 28, 2002. The newly restored airplane was returning to Boeing Field from Everett’s Paine Field when a landing gear malfunction delayed the landing. The airplane ran out of fuel and then ditched in the water. The airplane has since been restored and is part of the Smithsonian Collection. It is the last surviving Stratoliner. (Courtesy Gary Dawson.)