Chapter 18

WHATEVER IT TAKES

In the first half of 2012 the rotating presidency of the G20 fell to Mexico. On Friday, January 20, 2012, a week after the S&P downgrade of eurozone sovereigns, finance officials from around the world assembled in Mexico City. On their agenda was a remarkable request. The eurozone members of the G20 were calling on the rest of the world to contribute $300–400 billion in additional funding to enable the IMF to backstop crisis fighting, not in an emerging market or in one of the less-developed countries of sub-Saharan Africa but in Europe. The non-European members of the G20, led by the United States, China and Brazil, considered the European request and turned it down. As Mexico’s deputy finance minister remarked to the press: “There is a recognition of the measures Europe has taken. But it’s also clear that more needs to be done.”1

Amid the din of world events, the incident barely warranted a headline. But the location of the meeting, the nature of the request and the response by the rest of the G20 add up to a remarkable historical denouement. It was also indicative of the precarious state in which the eurozone was left hanging by the bruising battles of 2011. The G20 and S&P concurred: The Europeans had not done enough. They had not squarely addressed the basic instabilities with regard to the sovereign bond market and bank recapitalization, which had sucked the IMF into its engagement in Europe back in 2010. They had eventually recognized Greece’s insolvency and were on the point of pushing through a debt restructuring. That was essential, but haircutting Greece’s creditors served only to increase pressure in bond markets. In political terms, Europe had satisfied the German insistence on austerity, which Berlin promised would open the door to further steps toward integration. But December 2011 revealed how reluctant Berlin was to actually make the next move. Meanwhile, the consensus that had been built around austerity policies in 2010 was beginning to crumble.

The European fiscal compact of December 2011 was imposed by force of Franco-German cooperation. But Sarkozy was up for reelection in May 2012, and his main rivals for the presidency, the Socialists, were campaigning against the agreement. That was predictable. What was less so was that the IMF itself would be calling for a rethink. In its briefing for the full meeting of finance ministers and central bank governors that would convene in Mexico City on February 25–26, 2012, the IMF’s headline was stark. The “overarching risk” to the world economy was of an intensified global “paradox of thrift.” As households, firms and governments around the world all tried to cut their deficits at once, there was an acute risk of global recession. “This risk is further exacerbated,” the IMF went on, “by fragile financial systems, high public deficits and debt, and already-low interest rates, making the current environment fertile ground for multiple equilibria—self-perpetuating outcomes resulting from pessimism or optimism, notably in the euro area.”2 The place where the paradoxes of thrift were most visible was Greece.

I

In the protracted struggle to get to the October 2011 debt deal for Greece, the entire discussion had revolved around the Greek budget and concessions to be made by its creditors. The 50 percent haircut had been forced through in the hope of getting Greece to a debt level of 120 percent of GDP. From there, according to the mandatory fiscal adjustment procedure specified in Sarkozy and Merkel’s fiscal compact, it would be possible to get Greece down to a debt ratio of 60 percent of GDP, the target originally specified in the Maastricht Treaty. The fiscal arithmetic was pleasing, but what it ignored were the feedback loops highlighted by the IMF. The problem in achieving debt sustainability was Greece’s collapsing GDP as much as it was its elevated debt level. By the time of the discussions in Mexico in early 2012, it was clear that the deal hammered out three months earlier was no longer viable, not because the Greek government or the creditors were reneging but because the Greek economy was contracting too fast.3

For many European governments, at this point enough was enough. They could not ask their parliaments to consider yet another Greek rescue. It was time to consider more radical options. Rather than trying to manage a negotiated restructuring, perhaps it would be better to leave Greece to its fate. An outright default might result in Greece tumbling out of the eurozone. But Greece would at least be free of its debts. And if new borrowing was shut off, Athens would be forced to adopt fiscal discipline as a matter of sheer survival. It was in early 2012 that top-secret planning began for the eventuality of a Grexit.4 Work on the so-called Plan Z would continue until August 2012, when it was finally stopped by Berlin. It was stopped because the upshot of the planning exercises was always the same. It would likely be ruinous for Greece, and the ramifications of Grexit for the rest of Europe were entirely unpredictable. They were unpredictable because Europe still had not built an adequate shield to protect the other fragile eurozone members from the fallout from a Greek bankruptcy. It was to reinforce and extend that inadequate safety net that the Europeans were applying to the G20 to support an expanded IMF facility. But the G20’s answer was clear. The rest of the world would regard Grexit as a failure not just of Greece, but also on the part of the larger European states that pretended to global standing as members of the G20. On February 19, 2012, Japan and China, in a rare show of unity, declared that they were willing to back the appeal for increased IMF funding, but only if the Europeans raised the cap on the ESM stability mechanism, to which the Bundestag was clinging.5 The Europeans must help themselves first.

The ESM expansion would come at the end of March.6 Berlin blocked any truly dramatic move. But by counting the money already disbursed to Greece, allowing the EFSF facilities to continue and raising the combined lending limit of EFSF and ESM to 700 billion euros, Europe could claim that it was mobilizing a firewall of 800 billion euros or “more than USD 1 trillion.” It was a fudge that allowed the IMF board to sign off on continued support for Europe’s stabilization efforts. But what no one in Europe wanted to do in early 2012 was to renegotiate the Greek deal of October 2011.7 The governments had committed 130 billion euros and that was the limit. If Greece was sliding further away from sustainability, it was up to the Greek government to make further savings, and up to the creditors to make further concessions. A new round of negotiations with the IIF began in February, which yielded an increase in the haircut from 50 to 53.5 percent. What was left of the Greek debt would be exchanged for two-year notes backed by the EFSF and long-dated, low-coupon bonds. For this modest advance on the October program to offer any hope of fiscal sustainability, it would take extreme discipline on the part of Athens, and that begged the next question. Having ousted Papandreou as prime minister in a backroom coup after aborting his referendum proposal, the troika had fashioned for themselves a cooperative government in Athens. But by the same token, Papademos, the central banker turned prime minister, lacked legitimacy. Elections were scheduled for April 2012 and he would surely lose. The main opposition party, New Democracy, had presided over the onset of the crisis and had consistently refused to support Papandreou’s government in the negotiations since 2010. So that placed any new agreement with Athens in question from the start. How were the Greeks to be nailed down? With typical forthrightness, German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble suggested that perhaps it would be better for the Greeks not to hold elections.8 Suspending Greek democracy would allow the key measures to be put through before the voters were given a chance to have their say. But that suggestion provoked outrage in Athens. So, instead, what the troika managed to extract was a promise from the hitherto evasive leader of New Democracy, Antonis Samaras, that if he were to take office he would abide by any deal negotiated by his predecessors. Whatever happened in the elections, the fiscal program would have priority. On that basis Greece and its creditors engaged in the latest round of extend-and-pretend.

To describe the debt restructuring of 2012 in these terms—as no more than a continuation of the makeshift measures that had characterized the Greek debt crisis from the beginning—may seem unduly dismissive. The restructuring that was forced on the creditors of Greece between February and April of 2012 was the largest and most severe in history, larger in inflation-adjusted terms than the Russian revolutionary default or Germany’s default of the 1930s.9 By April 26, 2012, 199.2 billion euros in Greek government bonds were converted in exchange for 29.7 billion in short-term cash equivalent notes drawn on the EFSF and 62.4 billion in new long-term bonds at concessionary rates. All told, Greece’s private creditors had conceded a reduction of 107 billion euros. Allowing for the much later repayment of the new long-term bonds, the net present value of claims on Greece was cut by 65 percent. In December 2012 the claims of private creditors were further reduced by a buyback of the recently issued long-dated bonds.

Greek Public Debt Before and After 2012 Restructuring

|

Dec ’09 |

Feb ’12 bn euros |

Dec ’12 |

Feb ’12 % of debt |

Dec ’12 |

|

|

Bonds held by private creditors |

205.6 |

35.1 |

58.7 |

12.2 |

|

|

Treasury bills held by private creditors |

15 |

23.9 |

4.3 |

8.3 |

|

|

EU/EFSF |

52.9 |

161.1 |

15.1 |

56.0 |

|

|

ECB/National Central Banks |

56.7 |

45.3 |

16.2 |

15.8 |

|

|

IMF |

20.1 |

22.1 |

5.7 |

7.7 |

|

|

Total debt |

301 |

350.3 |

287.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Christoph Trebesch and Mitu Gulati, “The Greek Debt Restructuring: An Autopsy,” Economic Policy 28, no. 75 (2013): 513–563.

The problem was that the funds to sweeten the deal and induce the creditors to engage in the “voluntary” write-down did not come out of thin air. Nor did the money to pay for recapitalizing the Greek banks in the wake of the restructuring, or to pay for the December 2012 buyback. All this was funded by new borrowing from the troika. Furthermore, the 56 billion euros in Greek bonds held by the ECB were exempt from the 2012 restructuring. So the overall reduction in Greece’s debt burden was far less than advertised. As a result of the debt restructuring of 2012, Greece’s public debt was reduced from 350 billion to 285 billion euros, a 19 percent reduction. The really dramatic transformation was not in the quantity of debt but in who it was owed to: 80 percent was now owed to public creditors—the EFSF, the ECB or the IMF. In effect, Greece swapped a reduction of its obligations to private creditors of 161.6 billion euros for an increase in obligations to public creditors of 98.8 billion euros.

This substitution was the one constant in the endlessly shifting politics of Greek debt: public claims replaced private debts. And this is revealed even more starkly if we look not at stocks of debt but at flows of funds.10 Of the 226.7 billion euros that Greece was to receive in financing from European sources and the IMF between May 2010 and the summer of 2014, the vast majority flowed straight back out of Greece in debt service and repayment. Creditors in Greece and elsewhere received 81.3 billion euros in repayment of principal. Those creditors lucky enough to have debt maturing before the date of the restructuring were paid in full. It was precisely the arbitrariness of this outcome that led the IMF, under normal circumstances, to oppose emergency lending to insolvent debtors. For Greece they had made an exception on “systemic” grounds. On top of that, 40.6 billion euros were used to make regular interest payments, again to creditors in both Greece and the rest of the world. To sweeten the debt exchange of 2012, 34.6 billion euros were used to provide some incentive to those who had clung to their bonds. Recapitalizing the Greek banks, whose balance sheets were destroyed by the restructuring, took 48.2 billion euros. This meant that altogether, of the 226.7 billion euros in assistance loans received by Greece, only 11 percent went toward meeting the needs of the Greek government deficit and directly to the benefit of the Greek taxpayer.

The bond market was no longer the principal arbiter of Greece’s financial fate. But for that it substituted the full weight of the troika, the IMF, the EU, the ECB and the national governments of Europe. It was now with them that Athens would have to negotiate its financial future. This had two sides.11 On the one hand, as nonmarket lenders, the Greek Loan Facility and the EFSF could decide on loan terms by political fiat. In 2010 the terms had been punitive. By the spring of 2012 the EFSF was offering Athens long-dated loans on concessionary terms. Though the headline debt figure remained exorbitant, annual debt servicing charges were more modest. On the other hand, without the “private cushion,” the politics of Greek debt were now stark. Concessions to Greece came directly at the expense of the troika, and that meant, above all, the taxpayers of the rest of Europe. Negotiations would be tough and overtly political. And they could not be avoided. The 2012 restructuring had not answered the question of Greece’s solvency. The question of restructuring would return.

In 2009 when the crisis began, Greece’s public debt had stood at c. 299 billion euros.12 As a result of the crisis it had surged to 350 billion euros. The 2012 deal cut it back to 285 billion euros. But in the interim, as a result of the recession, the eurozone crisis and the policies demanded by the creditors, the Greek economy had crash-landed. Whereas in 2009 Greece’s GDP had stood at roughly 240 billion euros, in the course of 2012 it would slump to 191.1 billion euros.13 If Greece’s debts had been unsustainable in 2009, in 2012, even allowing for the concessions granted by the official creditors, it clearly still was. In the interim, Greek society had been battered beyond recognition.

In 2008 Greek unemployment had been 8 percent. Four years later it was rising inexorably toward 25 percent. Half of young Greeks were without jobs. In a nation of ten million, a quarter of a million people were fed daily at church-run food banks and soup kitchens. Meanwhile, the Greek parliament had been reduced to a factory for decrees demanded by the troika. In the eighteen months following the May 2010 bailout, the Athens parliament had whipped through 248 laws, one every three days. By 2012 it wasn’t only the trade unionists and the Greek Left who were up in arms. Judges, military officials and civil servants were mounting resistance to the subordination of the Greek state. And there were other ways of expressing dissatisfaction and distrust. In the spring of 2012 the draining of funds from Greek banks accelerated at an alarming rate. As the election now scheduled for May 2012 approached, the euro system was discreetly sluicing billions in cash into Greece to preserve a veneer of normality. In total, 28.5 billion euros were quietly airlifted into Greece to disguise the size of the bank run.14

On May 6 the population was finally given its say. The result was a spectacular demonstration of quite how deep disillusionment went.15 PASOK, the party that since the 1970s had been identified more than any other with Greece’s democratic transformation and which had had the misfortune of governing during the worst of the crisis, saw its vote share fall from 43.9 to 13.2 percent. The new left-wing movement, Syriza, together with the Communist KKE, garnered almost twice as many votes as PASOK. On the Right, New Democracy plunged from 34 to 18 percent, while the fascist Golden Dawn scored 7 percent. Even with the fifty-seat parliamentary bonus awarded to New Democracy as the leading party in the polls, no government could be formed. New elections were called for June 17. In the meantime, Greece hung in midair. There was no mandate for a government that was willing to accept responsibility for the measures that the Eurogroup insisted were essential for it to remain in the eurozone. As Schäuble and numerous other European politicians made clear, the Greek vote in June would be a referendum on its continued euro membership.16

II

The Greeks were not the only voters to deliver their verdict on the track record of Europe on May 6, 2012. That same day, in the second round of the French presidential elections, the voters rejected Sarkozy in favor of the Socialist, François Hollande.17 Sarkozy’s promise to hold France in line with Germany was not what the voters wanted. Hollande had campaigned on an antiprivilege, antibank platform, proposing taxes on higher earners and on financial transactions.18 He promised that he would renegotiate Merkozy’s fiscal compact of December 2011. The key to sound finances, as the new French government saw it, was not self-defeating austerity but growth. Crucially, Hollande gained not only the French presidency. The Socialists also won the National Assembly elections in June.19 There was a solid majority in France, it seemed, not for conformity to the Merkozy vision but for change.

And the mood was shared on the Left in Germany. Though they had coauthored Germany’s own debt brake, the SPD was alarmed by the disastrous development in the eurozone. They were soaring in the polls, and what the SPD demanded in 2012 was a new focus not on debt and fiscal sustainability but on growth. And this appeal received support from an unexpected corner: the IMF. The emphasis on the paradox of thrift in the G20 briefing for Mexico City was the first sign of a major shift in Fund thinking on fiscal policy.20 In the summer of 2012 its staff revisited the forecasts they had made in the spring of 2010 as the eurozone crisis began and discovered that they had systematically underestimated the negative impact of budget cuts. Whereas they had started the crisis believing that the multiplier was on average around 0.5, they now concluded that from 2010 forward it had been in excess of 1.21 This meant that cutting government spending by 1 euro, as the austerity programs demanded, would reduce economic activity by more than 1 euro. So the share of the state in economic activity actually increased rather than decreased, as the programs presupposed. It was a staggering admission. Bad economics and faulty empirical assumptions had led the IMF to advocate a policy that destroyed the economic prospects for a generation of young people in Southern Europe.

The conservative coalition in Berlin was losing its grip. In the French presidential election Merkel’s engagement on the side of Sarkozy had been unabashed. She refused to make even a token appearance with Hollande, who was publicly challenging the fiscal compact. It was probably to Hollande’s benefit. Now Berlin would have to hold the line without its major European partner.22 Nor were Merkel’s problems only across the Rhine. At home, the popularity of the CDU-FDP government was sagging. The coalition had been built on the extraordinary surge in support garnered by the market-liberal Eurosceptic FDP in 2009 in the wake of the first phase of the crisis and the unpopular bank bailouts. By 2012 that support was fading. On May 13 the CDU faced important regional elections in Nordrhein-Westfalen (NRW).23 With a population of 17 million and a GDP almost three times that of Greece, NRW was the largest state of the Federal Republic. Home to the Ruhr, it was a former heavy industrial area struggling to find a place for itself in a world in which China, not Germany, made the steel. Tellingly, the polls in NRW were triggered early because of the inability of its regional government to draft a budget in conformity with the debt brake that the grand coalition had imposed on Germany in 2009.24 For Merkel, the result was devastating. The SPD surged. A new protest party, the Pirates, entered the regional parliament, and Merkel’s CDU slumped to 26 percent. It was by far the worst result for her party in this crucial state since the founding of the Federal Republic.25

And then, as if to compound the political upheavals of May, the last aftershock of the real estate crisis struck, in Spain. Along with Ireland, Spain had the distinction of experiencing one of the most extreme housing bubbles in the world. When that burst, the effect, as in Ireland, was devastating. The difference is that Spain is big—with a population of more than 45 million, compared with Ireland’s 4.5 million. Before the crisis, Spain’s economy was comparable in size to that of the state of Texas. So the bursting of the Spanish bubble was an event of macroscopic proportions. As the housing market collapsed, Spain’s unemployment rate shot up. Of the 6.6 million increase in unemployment in the eurozone between 2007 and 2012, 3.9 million was accounted for by Spain—60 percent of that grim total. As bad as Greece’s situation was, it was small by comparison and accounted for only 12 percent of the increase in eurozone unemployment. Most catastrophic of all was Spain’s youth unemployment rate, which by the summer of 2012 had surged to 55 percent.26 Even allowing for an extensive black economy, it was a deeply dismaying statistic.

Unlike Dublin, Spain’s social democratic government managed to keep the travails of its mortgage banks—the regional cajas—out of the headlines in the first phase of the global crisis.27 A bailout fund took many of the worst loans off their books. In 2010 the weakest cajas, many of them entangled with Spain’s two leading political parties, were aggregated in a bad bank, Bankia/BFA. The number of cajas was cut from 45 to 17, but at the price of creating a larger and more dangerous entity. At 328 billion euros, Bankia’s balance sheet ran to 30 percent of Spanish GDP. Not surprisingly, despite endorsement by global investment banks, the attempt to sell Bankia shares to global investors was an embarrassing flop. In November 2011, as the crisis reached its height, the socialists called a snap election, which handed power to a new conservative government headed by the People’s Party of Mariano Rajoy. It is unclear whether Rajoy’s cabinet grasped the severity of the situation. Perhaps Spain’s Christian Democrats hoped for solidarity from Berlin. If so they were disappointed and Madrid’s tone toward the EU became more belligerent.28 New loss provisions called for from the Spanish banks were inadequate to calm the markets. By the spring of 2012 only huge injections of liquidity from the ECB were keeping Spain’s financial system afloat. But maintaining liquidity was not the same as restoring solvency. On May 9, 2012, Bankia declared that it was on the point of bankruptcy and urgently needed recapitalization. By May 25, with Bankia under new management, the figure had risen to 19 billion euros in new capital.29 With its economy already depressed, the last thing Spain needed was a new round of banking crises, and it would be even worse if a bank bailout spiraled, Irish style, into a bank-sovereign doom loop. Following the Bankia announcement, yields on Spanish public debt surged to 6 percent and then began to inch up toward 7 percent, above which Spain’s debt burden would begin to snowball as rising debt service costs further inflated the deficit.

By May 2012 it was clear that Europe was once again sliding toward the edge. Bond market yields were rising around the periphery. It was a dire outlook. According to IMF figures, in the course of 2012 alone, Europe’s governments and banks needed to roll over and refinance debts amounting to an impressive 23 percent of GDP.30 They simply could not afford interest rates to surge out of control as a result of a panic in Spain.

III

It was the looming crisis in Spain that forced the question of comprehensive eurozone reform, which had been blocked by Merkel over the winter of 2011–2012, back onto the agenda. At the end of April, speaking to the European parliament, Draghi called for a political road map to frame further moves toward fiscal union. Meanwhile, France’s new president and Mario Monti’s embattled government in Rome were coordinating their positions. With Italy’s yields inching ominously upward, Monti needed a Europe-wide fix. Would the Spanish crisis result in a basic change in position or simply another iteration of German delaying tactics? If Merkel continued to veto any talk of sovereign debt pooling, would she be more flexible on the issue of bank recapitalization? Would a banking union with collective responsibility for banking supervision and bailouts finally unlock the door to a eurozone solution?

On June 9, 2012, eurozone finance ministers agreed that the situation in Spain was so urgent that Madrid should be provided with 100 billion euros from EU resources to fund recapitalization.31 To stop the doom loop, however, what was required was a separate Europe-wide bank bailout fund that had the resources to intervene in and recapitalize banks directly. If instead the funds injected into the Spanish banks were booked to the Spanish government’s accounts, it risked amplifying the crisis. As if to prove the point, on June 14, 2012, Moody’s downgraded Spain to a rating of Baa3, one notch above junk. The future of the European Union, Spain’s foreign minister declared, would be played out in the next few days. And, as he reminded Berlin, when the Titanic sinks “it takes everyone with it, even those travelling in first class.”32 Indeed, the casualties list might stretch beyond Europe. Spain was not in Italy’s league. But from Spain the crisis could easily spread outward. As had repeatedly been the case since 2010, the eurozone’s failure to resolve its internal problems made Europe into the world’s problem.

In May 2012 the telephone log of Tim Geithner at the US Treasury shows an ominous spike, with dozens of calls to Brussels, the IMF and eurozone finance ministers.33 At the Camp David meeting of the G8 on May 18–19 Obama took Merkel and Monti aside for an eyebrow-raising two-and-a-half-hour side meeting. In November 2011, at the G20 in Cannes, the eurozone had dominated the talks. Nine months later, as the G20 summit convened in the glaring sunlight of the gated Mexican resort of Los Cabos, Europe was still at the top of the agenda. The world’s policy experts, politicians and media had to come to terms with the fact that the eurozone’s problems were not only not fixed but getting worse by the day. The impatience was palpable. At a press conference on June 19 the questions put to commission president Barroso were so aggressive that he lost his cool. In response to a Canadian journalist asking about the risks to North America emanating from the eurozone, Barroso snapped back: “Frankly, we are not here to receive lessons in terms of democracy or in terms of how to handle the economy. . . . This crisis was not originated in Europe. . . . [S]eeing as you mention North America, this crisis originated in North America and much of our financial sector was contaminated by, how can I put it, unorthodox practices, from some sectors of the financial market.”34 And continuing in this self-righteous vein, Barroso added that Europe was a community of democracies. Finding the right strategy took time. Several of the G20 were not even democracies. What did Europe have to learn from them?

Clearly, old hierarchies died hard. But, equally clearly, Europe needed help. At Cannes, Obama had tried to work through Sarkozy to shift the German position. That had failed. Sarkozy would not risk a breach with Merkel. By the summer of 2012, Washington had more levers to bring to bear. Italy’s premier, Mario Monti, had visited the White House early in 2012 and was hailed by Time magazine as a potential savior of Europe.35 Though he was the godfather of the Bocconi school of neoclassical economics and a classic Italian free-market liberal, Monti had become convinced that the eurozone bond markets could no longer be trusted. Speculators were pricing into their assessment of Italian and Spanish bonds not the particular fiscal situation in those countries but the probability of a systematic breakdown. The talk was of “redenomination” risk and for that there could only be a collective solution. But to shift the eurozone into action, Monti needed allies. Washington was supportive. But it was the break in the Merkozy front in May 2012 that was decisive. Not only was the newly elected Hollande pressing for a new emphasis on stimulus and growth but officials in the French Treasury were coming around to the idea of a banking union. The speculative pressure they had seen unleashed in the autumn of 2011 when Dexia failed and France’s own credit rating was in doubt had convinced them that without risk pooling no one was safe.36 As a third, Monti and Hollande could count on Mariano Rajoy, Spain’s Christian democratic prime minister. Rajoy was no visionary. Indeed, he often gave the impression that he barely grasped the extremity of Spain’s situation. But there was no doubt that Madrid desperately needed the talk of a eurozone breakup to end.

On the second day at Los Cabos, Obama and Monti sprang a trap. In a one-on-one meeting with Merkel, the American president presented the German chancellor with a plan that had been drafted by the Italians.37 The scheme proposed that for states that were running suitably responsible fiscal policies, the ECB or the ESM should put a cap on bond market yields. If yields rose above the threshold of sustainability, this would trigger intervention to restore a more normal level of interest rates. It would be a quasi-automatic mechanism that did not require intrusive inspection or supervision of the troika variety. Merkel indignantly refused even to discuss the idea on the procedural grounds that it had not been cleared in advance with her staff. She would accept no proposal that blurred the line between monetary and fiscal policy from whatever source it came. For the Germans the “autonomy” of the ECB remained sacrosanct. The tone was tense and it was thought that it would be best to cancel the after-dinner plenary that had been scheduled at Obama’s request. Enough had been said in private conversations. No one wanted to repeat the scenes at Cannes.

Once more Merkel had stopped a transatlantic push for emergency action. But pressure was now building on both sides of the Atlantic. On June 17, to general relief, the Greek election had clarified the political scene to the point at which a new government could be formed. PASOK was wiped out. Voters now clustered around New Democracy on the Right and Syriza on the Left.38 For those opposed to the troika Syriza was now the main choice. Samaras formed a government on June 20. A government was better than no government, but given Samaras’s track record during the crisis to date, it was hard to know what to expect. Would he stick to his commitment to honor the agreements of the Papademos government? The answer was far from obvious, and planning for the possibility of Grexit continued. In any case, by June 2012 Greece was no longer the main concern. If some concerted collective action plan was not put in place, Spain was in mortal danger and Italy would soon follow.

Scrambling for leverage, Monti and Hollande convened a meeting in Rome on June 22 to agree on a Growth Pact for Europe, notionally to be worth 130 billion euros in investments and tax breaks. They knew that Merkel was vulnerable because her FDP coalition partners were trying to save their skins by rallying the Eurosceptic vote and opting out of the chancellor’s European policy. This left Merkel dependent on the opposition SPD, who were coordinating their position with the French Socialists.39 The SPD demanded German backing for a growth agenda as the price for their votes in the Bundestag. Further multiplying the fronts on which Merkel had to fight, on June 26 the so-called quadriga—European Council president Herman Van Rompuy, European Central Bank head Mario Draghi, European Commission president José Manuel Barroso and Eurogroup chair Jean-Claude Juncker—returned to the vision that Berlin had vetoed in December. They proposed a banking union backed by eurozone-wide deposit insurance and a joint crisis fund. Nor did they shrink from suggesting the need for shared debt issuance.40 Merkel’s response was not long in coming. Within twenty-four hours she used a meeting of her coalition partners, the FDP, to announce: “There will be no collectivization of debt in the European Union for as long as I live.”41 In Germany the drumroll against additional eurozone bailouts was mounting. Merkel’s room for maneuver was further tightened on June 21 when the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that in agreeing with France’s demand to bring forward the creation of the ESM to the summer of 2012, the government had violated the Bundestag’s right to prior consultation. The message was clear. There must be no backdoor bailouts.

On June 28, 2012, the European Council convened in Brussels in an atmosphere of “deep crisis.”42 Spain was clearly sliding toward the abyss. Three days earlier Madrid had formally applied for 100 billion euros in external assistance to recapitalize and restructure its banks. To stop the impending disaster, there was no alternative but for the council to approve the creation of a banking union. This would provide for the direct recapitalization of banks, independent of their home country governments, once an effective overall supervisory regime was established. Finally, a structural solution adequate to the crisis was coming into view. In the short term Germany agreed to an immediate bailout for the Spanish banks, provided a strict stress test was applied. This was a step of enormous significance. Four years on from 2008, what Europe was finally acknowledging was that even more than a fiscal union, what the eurozone needed was joint responsibility for its financial sector.

What this did not resolve, however, was the boiling uncertainty in government debt markets. For Italy and Spain, facing interest rates rising toward 7 percent and beyond, this was a life-or-death issue. They could not hope to stabilize their public finances unless bond markets were calmed. On the evening of June 28 Monti and Rajoy forced a showdown.43 Just as council president Van Rompuy was about to announce Europe’s crowd-pleasing new Growth Pact to the press, they declared that they would veto the pact unless there was an agreement also to address the new crisis in sovereign bond markets. It was an ambush. For Merkel to have lost the Growth Pact would have left her vulnerable in the Bundestag. But she had also promised to hold the line on bank bailouts and bond buying and now she was at risk of capitulating on both. It took until 4:20 in the morning on June 29 for the chancellor to finally give way. After a negotiating session lasting a total of fifteen hours, Barroso and Van Rompuy went before the press to announce agreement not only on the Growth Pact but also on a plan that would permit support by the ESM for the government debt of all countries that were in compliance with the rules of fiscal governance agreed in December. It would be the entitlement of all eurozone members, not emergency assistance granted by way of a humiliating application to the troika. As he left the meeting, a jubilant Monti exclaimed, Europe’s “mental block” has been broken!44

It was indeed a breakthrough. But in both political and financial terms, in July 2012 the eurozone was still in flux. Merkel’s retreat did not pacify the German conservatives. The new Greek government was still regarded as a liability. Meanwhile, Spain was spiraling toward disaster. To trigger the bond market support mechanism, a eurozone member had to conform to the 3 percent deficit rule. Spain was a long way from that. In the summer of 2012 it was struggling to slash its budget deficit from 11.2 to 5.4 percent of GDP. The Eurogroup was still working out the details of the Spanish bank recapitalization. As the Spanish banking system suffered a silent bank run and the interbank lending market shut down, Spain’s banks drew a massive 376 billion euros in funding from the ECB.45 The regional governments across Spain were in trouble. In July Valencia applied to Madrid for aid. Catalonia might be next. On July 23 the Spanish ten-year bond surged to 7.5 percent and its CDS shot up to 633 basis points. That same day the Spanish minister for economic affairs, Luis de Guindos, jetted to Berlin in the hope of obtaining an endorsement from Schäuble that might reassure markets and open the door to ECB bond buying. Spain was facing, De Guindos warned, “an imminent financial collapse.”46 But Schäuble was grudging in the support he was willing to give his fellow Christian Democrat. For Germany to approve immediate bond buying, Madrid would need to make changes to its pension system and demonstrate its commitment to budget balance. Conformity to Germany’s idea of the European social bargain was the price for backing from Berlin. The eurozone still hung in the balance.

Three days later, on Thursday, July 26, Mario Draghi flew to London ahead of the opening of the Olympic Games to attend a Global Investment Conference designed to promote the UK as a business center. The mood in London was not friendly.47 Mervyn King, speaking ahead of Draghi on the panel, let it be known that he did not regard European political union as a possible solution. As Draghi later confided to a friend: “I really got fed up! All those stories about the dissolution of the euro really suck.” The expression he used in Italian was apparently rather more colorful.48 So Draghi decided to change the script. The markets needed to understand the qualitative change that Europe was undergoing. The eurozone might have started life as an ill-shapen construction, but under the pressure of the crisis it was developing fast. Global markets needed to appreciate the fundamental changes that were reshaping Europe. Following the December 2011 fiscal pact, the summit of June 2012 was a turning point because for the first time since 2008 all the leaders had restated with a powerful voice that the “only way out of this present crisis is to have more Europe, not less Europe.”49 The forward motion of the EU’s integration machine was resumed. The point that Draghi wanted to drive home to global markets was political. “When people talk about the fragility of the euro and the increasing fragility of the euro, and perhaps the crisis of the euro,” he told the skeptical City of London crowd, “very often non-euro area member states or leaders underestimate the amount of political capital that is being invested in the euro.” These were not empty words because “actions have been made, are being made to make it irreversible.” And there was “another message” that Draghi wanted investors to hear: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro.” Then, pausing for effect, he added: “And believe me, it will be enough.”

IV

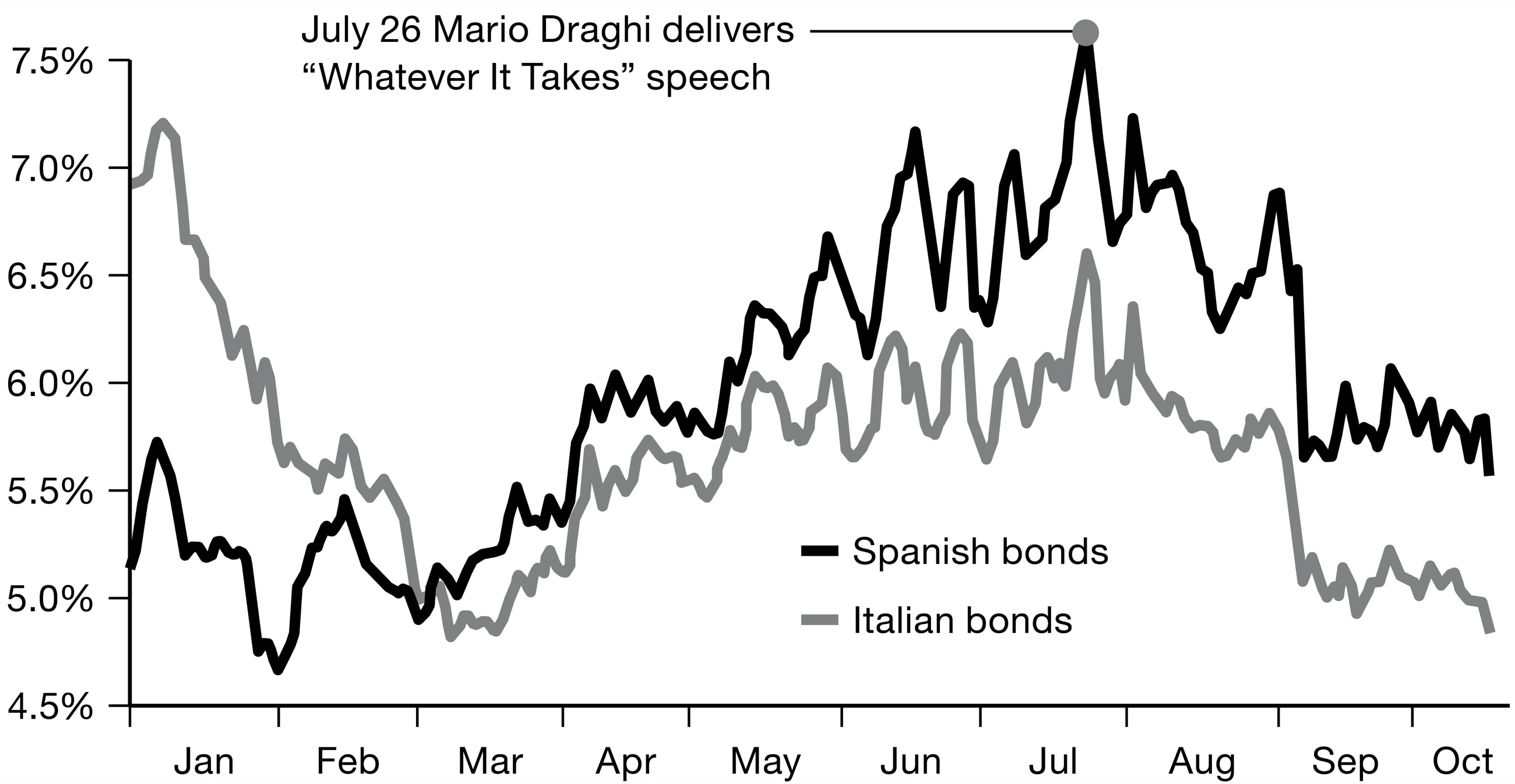

In retrospect, Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech has come to be seen as the turning point of the eurozone crisis. In the aftermath, markets immediately calmed. Yields for the most vulnerable borrowers came down. There was no more talk of a eurozone breakup. It is an explanation with deep appeal. The ECB had held the key to stability all along. Draghi, finally, was the one to turn it. But this is a retrospective construction. The more or less open struggle over the direction of ECB policy that had begun back in 2010 was not ended by Draghi’s speech on July 26. His initial intervention was extremely fragile. It could easily have been undone. It took a lot of help to make Draghi’s speech into a historic turning point, and even then it was painfully incomplete.

Whatever It Takes: Spanish and Italian Sovereign Bond Yields, January–October 2012

Source: Thomson Reuters, from Marcus Miller and Lei Zhang, “Saving the Euro: Self-Fulfilling Crisis and the ‘Draghi Put,’” in Life After Debt (Basingstoken, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 227–241.

In the hours that followed Draghi’s address, as its import sank in, there was confusion at ECB headquarters in Frankfurt. As one senior ECB official commented to Reuters: “Nobody knew this was going to happen. Nobody.”50 The ECB’s media department and the editors of the bank’s Web page did not have an advance copy of the speech to make available to the press. Draghi had vaguely discussed his plan with a few of his fellow executive board members. But given its likely impact, he had clearly felt it was better to hold the decision close and to present the world with a fait accompli. Significantly, Jens Weidmann, president of the Bundesbank, was among those who learned about Draghi’s message through the news. None of Europe’s capitals had received advance warning, nor had Klaus Regling, the head of the EFSF, whose agency would play a key role in Draghi’s plan. Draghi had had “nothing precise in mind,” said an official at the ECB’s headquarters in Frankfurt. “It was a rash remark.” As Reuters put it: Draghi’s “words were a gamble. . . . [T]he speech was just the beginning.”

If Draghi’s speech was a rallying call, what mattered was who followed. Over the weekend, Eurogroup chief Jean-Claude Juncker threw himself behind Draghi: “The world is talking about whether the eurozone will still exist in a few months,” he declaimed. Europe had “arrived at a decisive point.”51 Juncker warned the German government about allowing itself the luxury of “getting caught up in domestic politics in euro questions.” Meanwhile, Merkel, Monti and Hollande issued joint statements insisting on their determination to hold the euro together. To complete the eurozone quadrilateral, Monti announced that he would shuttle to Madrid to meet with Rajoy.

Washington was quick to jump on Draghi’s bandwagon. On the morning of Monday, July 30, Treasury Secretary Geithner flew to Europe to visit Schäuble at his vacation residence on Sylt. The media were divided over what transpired. Some reported agreement, others a dogged refusal by the German to compromise.52 Geithner was concerned that Germany was still toying with dumping Greece out of the eurozone. As he wrote in his memoirs: “The argument was that letting Greece burn would make it easier to build a stronger Europe with a more credible firewall. I found the argument terrifying.” Letting Greece go could create “a spectacular crisis of confidence.” The flight from Europe “might be impossible to reverse.” It wasn’t clear to Geithner either “why a German electorate would feel much better about rescuing Spain or Portugal or anyone else.”53 After seeing Schäuble, Geithner dropped in on Draghi in Frankfurt. As Geithner later recalled, the upshot was far from reassuring. Draghi told Geithner that his remarks in London had been prompted on the spot by the deep skepticism he had sensed in his audience of hedge fund managers. He realized that he would need to shake the markets. As Geithner put it, “[H]e was just, he was alarmed by that and decided to add to his remarks, and off-the-cuff basically made a bunch of statements like ‘we’ll do whatever it takes.’ Ridiculous . . . totally impromptu . . . Draghi at that point, he had no plan. He had made this sort of naked statement.”54 On his return to Washington Geithner was pessimistic: “I told the President that I was deeply worried and he was, too. . . . [A] European implosion could have knocked us back into recession, or even another financial crisis. As countless pundits noted, we didn’t want that to happen in an election year, but we wouldn’t have wanted that to happen in any year.”55

In fact, German opposition to Draghi’s initiative was fierce.56 Some insiders are convinced that it was not until the German government’s joint meeting with its Chinese counterparts on August 30 that Merkel and Schäuble were finally committed to backing the ECB’s initiative and holding Greece in the currency zone.57 Chinese prime minister Wen Jiabao certainly made clear that he held the major European countries, Germany and France, responsible for the destiny of the eurozone and that continued Chinese purchases of European bonds depended on their taking effective action.58 Perhaps the position of the Obama administration was too familiar by this point and the battle lines too clearly drawn to carry much additional weight. As usual, the inflation hawks at the Bundesbank were aghast at the idea of ECB bond buying. But for Merkel it was the better of two bad options. For Spain to have been supported out of the funds of the ESM would have raised far more serious political and legal issues.59 On September 6 the Bundesbank made its displeasure known by casting the lone vote against Draghi’s plan. Indeed, Weidmann was so indignant that he demanded an interview with Draghi to impress upon him that the Bundesbank should not be regarded as just another vote on the ECB’s council. It must have a veto.60 But with backing from both Merkel and Schäuble the die was cast. The ECB formalized its new role as a conditional lender of last resort, under the title of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT).61 But this was a strictly conditional promise. The ECB would go into action only if the country in question had agreed on an austerity and aid program approved by the ESM. It was hedged with far more conditions than the unconditional bond buying in which the ECB had engaged under Trichet.

Even after Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech, the ECB’s monetary policy was profoundly constrained. The same was not true to the same degree for its counterpart in the United States. In 2012 the pace of the US recovery was flagging. The conservative stampede that had opposed any further expansion of monetary activism in 2011 had run its course. On September 13, 2012, the FOMC voted for QE3.62 It would be the biggest Fed expansion yet. Initially, the Fed committed to purchasing $40 billion per month in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac agency bonds. What was different was that it undertook to do so until the Fed saw “substantial improvement in the outlook for the labour market.” Additionally, the FOMC announced that it would likely maintain the federal funds rate near zero as long as unemployment remained above 6.5 percent and the Fed’s inflation forecast did not exceed 2.5 percent. On December 12, 2012, the FOMC announced an increase in the amount of purchases from $40 billion to $85 billion per month. Because of its open-ended nature, QE3 would earn the popular nickname “QE Infinity.”

In his memoirs, Bernanke commented: “Like Mario Draghi, we were declaring we would do whatever it takes.”63 But this was far too kind to the Europeans. Draghi’s OMT as it emerged by September 2012 was a conditional confidence-building measure. It worked by calming markets and stopping the panic. But beyond that it provided no stimulus to the eurozone economy. In truth, the ECB’s possibilities were limited. QE for Europe with Germany’s conservatives on the warpath was unthinkable.64 As the eurozone economy stagnated and its banks deleveraged, the LTRO facilities were progressively paid back. Unlike the Fed, whose balance sheet Bernanke was actively expanding, the ECB’s balance sheet contracted back to where it had been in the crisis-ridden fall of 2011. Europe was sliding ever deeper into its second recession.

Fed and ECB Balance Sheets, 2004-2015

Source: Fed, ECB.

V

If one asks how the acute phase of the eurozone crisis was finally halted, Draghi’s July 26 speech offers two answers. One was that given by Draghi himself. The eurozone crisis was halted because of the enormous investment of political capital made by Europe’s governments. It was halted by the construction of a new apparatus of government: the Greek restructuring, the fiscal compact, banking union, ESM, the ECB’s OMT facility. Those who bet against the eurozone’s future misjudged the scale of the investment being made by Europe’s governments. That was the message that Draghi wanted to ram home. As Draghi said, it was a political message about the seriousness of European state building. The delays might come at a huge cost to its citizens. But in its usual crablike fashion, Europe was moving once more toward “ever closer union.”

But the answer extracted from the speech by most of those who heard Draghi that day in the City of London was rather different. They remained skeptical of the EU and uninterested in the details of its politics. What they took from Draghi’s speech was not its specific content or the sea change in eurozone politics that made it possible. They heard one single and simple message. Here was a powerful central banker and he was saying that he would do “whatever it takes.” Finally, a European policy maker had realized what was needed. He was speaking the language of the financial Powell Doctrine, in the City of London, to an audience of investors, in English. What Draghi was signaling was that Europe, finally, “got it.”

Implicit in this rendition of what happened in the summer of 2012 is another narrative, at odds with Draghi’s intended meaning. “Whatever it takes” was, in fact, a form of surrender. The eurozone was finally giving in to what Anglophone economic commentators had been calling for all along. If only the ECB had moved to the Fed model earlier, as Obama had spelled out at Cannes, the worst of the eurozone crisis might have been avoided. What Draghi now promised was what Geithner, Bernanke and Obama had been preaching to the Europeans since 2010: “Do it our way.” Nor was it a coincidence that it was Draghi—an American-trained economist; a Goldman Sachs associate; a paid-up member of the global financial community; a “friend of Ben”; an internationalized, urbane Italian, not a provincial German—who delivered this conclusion to the agonizing story of the eurozone crisis. The Draghi formula—America’s formula—was self-fulfilling. He spoke the magic words. The markets stabilized. The eurozone was saved by its belated Americanization.

Looking back over the course of events since 2007, if one stopped the historical clock in the autumn of 2012, the story of the North Atlantic financial crisis could thus be twisted back into a familiar shape. Faced with a crisis of historic proportions, after its own fashion, the Obama administration had delivered a twenty-first-century demonstration of hegemonic leadership. It lacked the urgency and razzmatazz of the Marshall Plan era, but the upshot was decisive. Not only had America led the way through its own domestic stimulus and monetary policy programs. Through discreet diplomacy and the Fed’s massive liquidity programs, it had helped Europe across its worst crisis since the end of World War II. Americanization was the answer. Nor were the exponents of US economic policy shy about trumpeting their achievements. The Courage to Act would be the title of Bernanke’s memoir. The melodrama caused his more bashful European colleagues to wince. It was not the kind of language one associates with the recollections of an academic economist turned central banker. Other, more academic titles in the wake of the 2012 stabilization echoed the general mood of optimism. In the end, it had turned out to be a Status Quo Crisis.65 The System Worked.66 The global economy had survived and America had reasserted a new version of liberal hegemony. Europe resumed the forward march to a United States of Europe it had begun under American guidance in 1947. Among academic commentators, a cottage industry grew up on both sides of the Atlantic benchmarking Europe’s new efforts at integration against American history. Was Europe still at the Philadelphia stage, or was a Hamilton moment on the horizon?67

It was, one should add, a reasonable assessment, certainly if one stopped the clock in November 2012 and if one skated over America’s unfortunate role in 2010 in endorsing the first round of extend-and-pretend. This narrative was also, in the American context, a thoroughly political one. As Geithner acknowledged, 2012 was an election year. And if the financial crisis and its European aftermath had finally been contained, the Democrats deserved whatever credit was due. Since 2008 the congressional Republicans had been obstructive if not downright dangerous. Campaigning for a second term as president in 2012, Obama cashed in. Gone was the modesty that characterized his speeches in 2008–2009 in the wake of the embarrassment of the Bush presidency. Now Obama trumpeted American exceptionalism without reserve: “I see it everywhere I go, from London and Prague, to Tokyo and Seoul, to Rio and Jakarta,” he declared to a group of air force cadets in the summer of 2012. “There is a new confidence in our leadership. . . . [America remains] the one indispensable nation in world affairs. . . . I see an American century because no other nation seeks the role that we play in global affairs, and no other nation can play the role that we play in global affairs.”68 As far as international economic policy was concerned, Obama’s victory in November 2012, Bernanke’s QE3 and Draghi’s speech combined to put the seal on the narrative. Centrist liberal crisis management had prevailed. In America’s new century, diversity, world openness and technocratic pragmatism would go hand in hand.

But this reconciled narrative of crisis resolution obscures deep tensions on both sides of the Atlantic. In Europe, the eurozone had survived. Draghi was right. An important phase of state building had emerged from the crisis. But it was at an appalling economic and political cost. The governments of Italy and Greece had been overturned. Ireland and Portugal had been put on troika tutelage and Spain had escaped by the skin of its teeth. And though the acute sovereign bond crisis was over, after two years of nail-biting anxiety, consumer and business confidence were shot. Unemployment took a huge toll on eurozone demand. Fiscal policy was constrained by the German drive to balance budgets. Perversely, Germany’s trade surplus was surging at a time of plunging aggregate demand across the continent. It was a time, if there ever was one, for an active monetary policy. But stopping the bond market panic was one thing, reviving the eurozone economy another. Unlike the Fed, Draghi had no mandate. As social misery deepened, as the sense of humiliation set in, what would be the reaction across Europe? Nor was it only the “victims” who were unsatisfied. German conservatives were indignant at Merkel’s litany of compromises. In the German media, Draghi, the savior of the eurozone, faced hostility and doubt. Unless this German Euroscepticism could be overcome, there was little prospect of actually realizing the agenda of ambitious integration and institution building that Draghi had trumpeted in his London speech.

In the United States, Obama’s reelection might energize his followers. But what exactly did his new American century consist of? What would be its priorities? In his first term Obama had been preoccupied with overcoming the legacy of Bush’s mistakes and coping with the crisis. But was the crisis really over? And even if it was, did that mean that America could face the future unencumbered? Or, having survived the crisis, did America now face the same challenges that had brought Obama as a junior senator to the launch of the Hamilton Project in 2006—challenges that had only amplified and intensified since? In foreign policy circles the beginning of Obama’s second term saw an impassioned argument over American retrenchment and the foundations of its international power.69 And in economic policy too there were skeptics. Had enough really changed to make another crisis less likely? Had the tensions within the financial system really been resolved, or merely contained? If another Great Depression had been avoided, did that have the perverse effect of removing the spur to truly profound reform?70 It was not without irony that among the Cassandras one of the loudest and most compelling voices was none other than Larry Summers, Treasury secretary to Clinton and chief economic adviser to Obama until December 2010. Twelve months on from Obama’s second election victory, at an IMF event in November 2013, Summers warned: “[M]y lesson from this crisis, and my overarching lesson, which I have to say I think the world has under-internalized, is that it is not over until it is over, and that time is surely not right now.”71 He could not have known how right he would turn out to be.