III

COLONY OF LIGHT

2000–2001

10

Henry

San Jose, 2000

By age seventeen, I could read the valleys after school. I asked of a paw print—who? The glow in the distance—where? And the broken cobweb—when? Light passed through the wings of a moth onto my palm. I tracked soft impressions in the tall grass until I came to the resolution of a chase—a den. Dogs came over the hill, puffing from their run. As I mapped the town, my senses lifted off the ground. From a bird’s-eye view, I had no feeling of a separation. The moment life showed itself in the brush, I held still above the earth’s roots. Though I came and went, from the townhome to the school to the valleys, I didn’t go missing. I could be found as soon as you looked for me. I’d come to you even if you couldn’t follow me, and I didn’t worry anybody.

These June days, marked by an apocalypse that never came, my face whiskered and my hair tucked behind my ears. I could read my mother and father, who slipped into their bedroom and impressed me for the first time with their laughter. With my grandmother gone, they became harmless like clear soup. Most days, my mother looked for my father, whose face curled tightly with excitement at the sound of her voice. My father drew her out of her dark moods in such a way that I could see her as a girl lying awake at night, a shadow on her cheek, rolling the late hours between her palms into the ball of morning. Then without warning, my parents disappeared into their room, nodding like horses.

I could read Robert at the pool hall, who walked to and from the rear as if painting lines with the bottoms of his shoes. Every time Robert heard footsteps at the door, he raised his head. When he noticed me, he looked as if he’d ask me a question but said nothing. Robert dissolved his businesses and devoted himself to the hall, where men assembled in falling numbers since the crash and the layoffs. He invited activists, city council members, company presidents, but his words didn’t travel farther than the pool cue chalk. Only a decade ago, Robert had men and women vibrating at his ears. He couldn’t give up, so he hired a young woman to transcribe his writings. The young woman made a clear impression on me: her heart-shaped face with wide, dark eyes and perfect teeth. She seemed to watch me closely when I walked up, opening the door like a trap.

~

It was Sunday afternoon—still summer. The sun split my onion skin. I biked in the opposite direction of the townhome—I had no plan. Any creature leaves ripples in its wake, so I followed a metallic taste in the air. I was cutting through the Ohlone College campus, sandbox-square buildings on foothills with red signs and green arrows, when I spotted the young woman from the pool hall. She was slogging a poster across the quad. The young woman was a college student, but it hadn’t occurred to me until I saw her on campus. She propped the poster against a skinny tree on a square of earth in the cement. And stood in front of it with her arms out, as if she had put herself on a coatrack, a cross, as if she were jumping out of a plane.

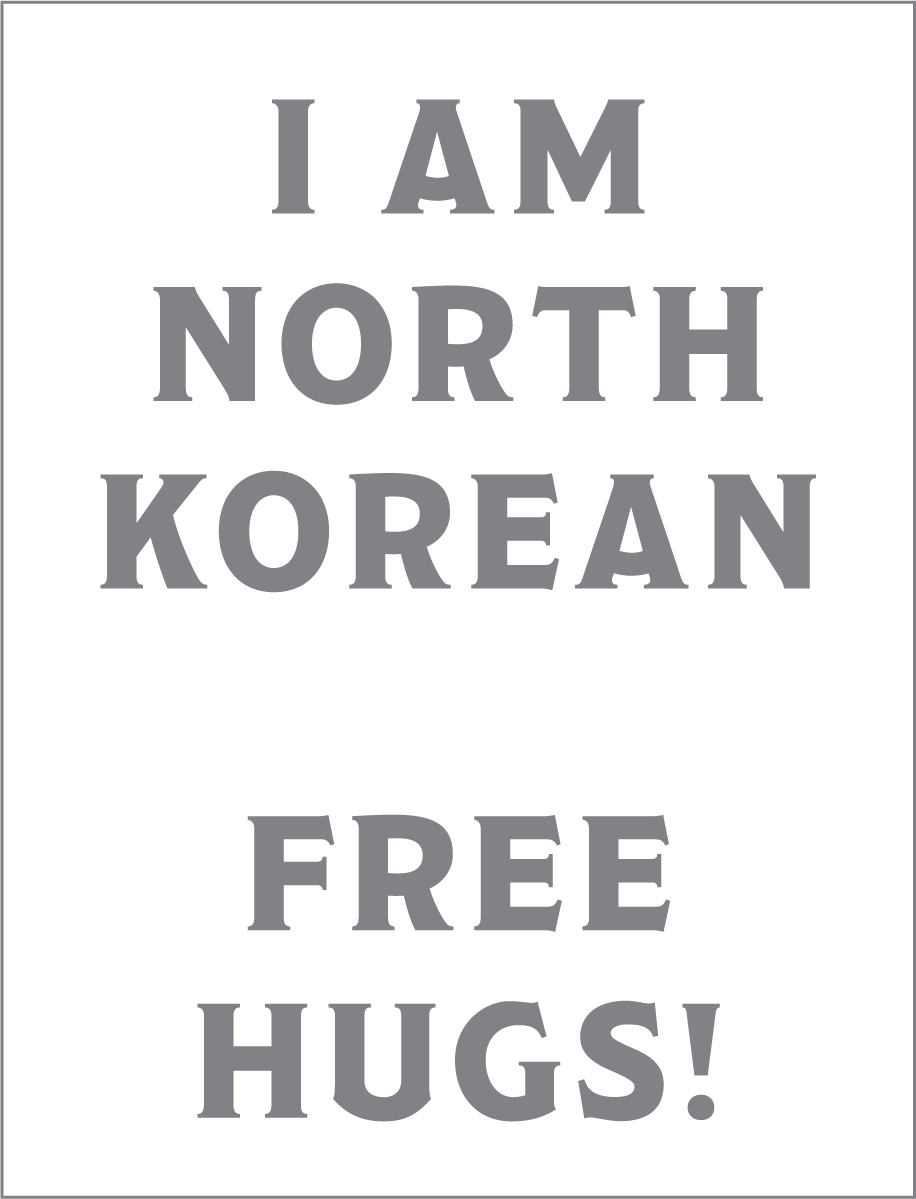

The poster read:

A child paused at the sign. “Are you North Korean?”

“I am,” the young woman said.

The child ran to his mother. His mother said it was an act, a performance. They pondered the sign from the edge of the quad.

The young woman raised her arms higher. People stopped to read but wouldn’t get close. I watched from the basketball court. The bell rang between summer classes.

One professor halted in front of her. The professor had on a sweater over a modest skirt. “When’s the last time you ate?”

The young woman said nothing.

“You don’t stay overnight on campus, do you?”

She dropped her arms. “I don’t live at the school if that’s what you mean.”

The professor pushed cash on her. “You’re saying you won’t get touched as a North Korean? What’s your point?”

The young woman’s name was Jennie. Her English was excellent. So were her Chinese and Korean. Her colloquial English came from being a caregiver to elderly Americans before working at the pool hall. “Beijing was shipping defectors back to North Korea. I was eight when I had to escape China,” she said. “We fled to Mongolia. Rumor was Mongolia traded with South Korea—people for trees.”

“People for trees?” The professor said it was a lie.

“Mongolia needs trees because of its deserts.”

“They got trees for you?”

Jennie frowned. “It’s a fair trade. Americans will need trees soon. I’m an eighteen-year-old tree,” she said. “It’s strange how you Americans worship your politicians. The way you buy political merchandise and wear it, like sports teams.”

The professor smiled wryly. “If you’re a defector, don’t they put you in an Ivy League? Don’t tell me you’re a slacker.”

“I applied for Ohlone while I was sleeping in libraries,” Jennie said. “I was homeless since no one hires defectors in the South. But I’ve made it to the same place as you.”

The professor said Jennie was lucky to be here.

Jennie said she dreamed of becoming a high-tech assembly line worker, fired for complaining about respiratory illnesses.

“How many trees they give for you?”

Jennie said the professor’s joke was expected. Americans felt uneasy about death and suffering. But the economics of capitalism were the same as death—the value of human life.

“It’s not how many trees,” Jennie said. “It’s what kind.”

“Ah, psychology.” The professor cracked a smile. “You go on sprouting, then.”

When the professor left, so did the mother and child.

Jennie fixed her poster and raised her arms.

I couldn’t help myself. Tossing my bike onto the court, I crossed the quad in a few strides and fell straight into her arms.

We stood embracing. To my surprise, she didn’t feel tense at all. “You.” Her tone was relaxed. “You’re Henry, right?”

“You can’t have your sign up for hugs and stand here alone,” I said. “People will think something is wrong. The professor was taking over your sign.”

“So you’re righteous.”

“If you think so,” I said. “People need to see what they’re supposed to do. We’re like animals.”

“Then you’re reckless.”

Few approached the quad.

“I’ve never been reckless.” I told her to watch what happened around us. “No one crosses into something that looks dangerous. They feel accused by you. They’ll only come for something they want for themselves.”

Just then, another bell rang, and a group of ten or so others walked around us. Some stopped to observe us.

“A crucifix feeds on the past,” and I lowered my arms without letting her go. “What you need is a different sign.”

“I see,” Jennie said. “The desire to be rebellious fades with the desire to belong.”

Five, six, then seven joined, holding our shoulders.

I pointed across the quad at the professor, who had stopped to watch us. “The hug isn’t for you,” I said. “It’s for her—it’s for us.”

Jennie took in the forming crowd. “Why’d you come here?” she said. “I’m not on your side.”

Twenty or thirty others corralled around us. Bunched shoulder to shoulder with their arms hanging over each other.

“I thought that was the point,” I said. “That we’re not on the same side.”

“What a surprise,” Jennie said.

Hundreds of students gathered that day on the quad. They came from the basketball court and the classrooms and the library. Jennie said it was like when she’d first arrived in Incheon. Standing under the recessed lights of the empty baggage claim, before the government stopped housing her, before her bosses accused her of stealing and grilled her about Northern girls with round faces and red lips, before the Seoul hell where her skin was no longer dusted with powder off the mountains but with ash off the cigarettes, she’d recognized a flash of humanity in a billboard sign. Two figures stood in the center—soft, persistent focus. Shadows crisped the edges. Scratches lightened the grain. No weather, no grass. You might have believed that even the most intractable conflicts could be resolved. The picture of lovers looked unbearably light, as if it weighed nothing at all.

~

Horrible things were usually preventable. They transgressed moral and rational boundaries. Otherwise they were terrible. Like a terrible earthquake, a landslide. God’s mud. On a weekend night at the pool hall, Jennie counted the register, moving her lips without a sound. Robert disappeared for days at a time. When I asked her about it, she rolled the bills under the tray. “Robert’s running out of money, and he’s losing friends. Now his customers are younger—recent grads without jobs. The irony is that his dream to unify people has isolated him. There’s a reason we haven’t unified in fifty years. But he’s obsessed with some kind of plan.”

Jennie’s hands pushed through her jacket sleeves. I asked why she worked for him, and she said, “Only Robert would hire me. I can work until the whole strip is bought up by developers and turned into an office complex.” We stepped through the doors and out into the ordinary world. Jennie padded the rear rack of my bike with Robert’s writings—precious thoughts he’d put on paper—and sat on them. It seemed as though one must live one’s thoughts, or they’d become merely a cushion. She dangled her feet so they wouldn’t catch the spokes or my pedaling heels.

Pointing, she directed me twenty miles down a path along Stevens Creek Trail to a lagoon.

Jennie said, “Robert’s forty-five now. He’s planning to go to Korea by himself. But it’s dangerous—he’s been too loud about his ideas.”

I rode around a pothole. “So you’d heard of him before you started working at the pool hall?”

“Who hasn’t heard of Robert?” She played with my loose hair. “Robert talks about an auditorium near the Port of Busan. He’s probably going to head there.”

We passed through a tunnel. Popped out under the trees. “You’re not one of his lackeys, are you?” she asked.

Riding into the tailwind, we picked up speed.

“I’ve watched him since I was five. Robert gave me a dog and saved his life,” I said. “Robert listens to Journey. His favorite song is ‘Don’t Stop Believin’.’ He wants coexistence. He’s just an exile who wants to be loved by the country that exiled him.”

Then a bird flew into my periphery, and I thought of paws pressing on my collarbones, a wet leathery snout resting on my chest—so that bird I just saw had to be Toto.

“Robert’s favorite movies happen to be the same as Kim Jong Il’s—the James Bond films. He plays them in the pool hall all the time.” The wind picked up, she leaned closer. “They order the same drinks, drive the same cars.”

“Who doesn’t like those movies?” I said. “You think they’re worse than Titanic?”

“Koreans love Titanic. Because it’s so Korean.”

I slowed my wheels on a merge.

“People with high moral authority are dangerous,” Jennie said into my ear, her words like silk spilling out of a magician’s hat. “Their egos depend on their ability to see themselves as moral, so they become dictators just as quickly as they become leaders.”

~

It was dark at the lagoon. Jennie could see and hopped over the plastic mesh fences. Stiff grass stopped at the bar of white sand. I heard of the salt flats and boat launches but not this place. The wind blew through the trees, whose branches moved as if underwater. The cold water came up to my ankles and split in two. The sound of wings splashing in the lagoon. Swings, with no one in them, going back and forth in the playground. Behind me, mountain ridge knuckles gripped broad, flat valleys. The fronds minted the air. Scalloped skies appeared through the understory. The stars were like holes in a vast gray tarp. The last clouds wagged their tails as they broke off. Jennie picked up her sandals by the strings, and her bare feet rolled with the dips in the beach.

We tossed our clothes, waded into the water.

The water came waist-high at the buoy. The silver surface rippled, shining into the back of my eyes.

The signs warned, No lifeguards on duty.

Jennie reached me at the buoy. Under her arm, she had Robert’s papers.

When she crossed my sight on the horizon, I drew out a page of Robert’s life. “If Robert wanted to hurt somebody, it’d be different. If he believed he could hurt anybody, he would’ve done it already.” Robert often kept an eye on his watch, and I couldn’t tell whether he wanted time to go slower or faster—or whether it was time that wouldn’t let go of him. “If he shared his ideas and found out he was wrong, he’d apologize.”

Then she tossed Robert’s papers into the air, page by page, as if hundreds of insects tore out of their pale molts—blowing away in the wind. Jennie had no qualms as the sheets landed on their backs and floated in circles around us.

“Why’d you do that?” My voice pitched forward as if to catch the thin sheets.

“Robert’s a corrupt guy, and Korea has one of the most corrupt systems in the world. The human rights groups endanger the people they’re meant to protect, risking the lives of defectors to get support funds from countries like the US, who want to further their own image of moral leadership,” she said. “Networks pay celebrity defectors, protected by the state, to demonize North Koreans. A chosen percentage speak on behalf of North Koreans everywhere.” Jennie shivered in the swell. “Reunite the country to free North Korea? Who says? The human rights groups that smuggle USB drives into the North and trigger their authorities to execute families? Human rights issues are corrupt. All of it is supposed to fail. Without captivity, there is no liberation.”

She stood straight as if her words caught the bottom of the lagoon.

“Don’t be stupid, Henry. You don’t know about defector suicides in the South. Judicial officers won’t report them as what they really are—murders. Defector deaths pile up as paperwork in Seoul’s main office, boring public servants, and only once in a while surprising the public. The North never had a monopoly on North Korean deaths.”

Time was horrible until it stopped, then it became terrible. My mother’s bottommost drawer was horrible until it was filled—her singed uniform, a hospital throw, and two hanboks that didn’t fit her—then it became terrible. It was horrible that as my mother and father aged, they missed their own parents. It was terrible that everyone became an orphan eventually. Horrible that my parents would lose half their memories if they ever split up. Terrible that they stayed together for what they hoped to remember. The Robert I knew couldn’t be horrible, but if he were to leave us now, he might become terrible. The way an iceberg at sea was terrible. The thing about the lifeboats onboard was horrible. But a sinking ship was always terrible.

Jennie hooted with laughter. “But whatever, right?” She kicked the water, making the papers float away.

Jennie waded closer and told me it was remarkable what I didn’t know—yet it was this very part of me she was drawn to because it remained untouched. The water nudged my spine left and right, and I let my arms rise up, inching toward her. She was suspended in the water, leaning slightly back. I dug my feet into the sand, my heels anchoring me. Scooping the water, she kept herself in place. The moon reflecting off the sand below illuminated her in the dark. The light turned us translucent—into the color of the water. I saw the upward curve of her spine, the brushstroke of her thighs. The water dried on our shoulders. I looked down at the elaborate braid of our bodies, and we began to move. We rocked together, rolling with the drag.

~

By morning the papers had disappeared. Jennie wouldn’t ask me about them. I’d picked them up and strung them on my bike as if drying them out on a line, and I rode home with them. Sheets of ink-stained paper flapped around me, trying their wings in the headwind as I pedaled. One page hanging from my handlebar I could still read through its broken ink. I recognized it as Robert’s credo—a poster sign he stood up over the earth: Fratricide is, by definition of the shared human condition, suicide. Every human on the planet has a responsibility, one that deserves reflection and careful action, to the reunification of the Koreas and ultimately to ourselves.

On the way back, I stopped by the pool hall. I placed the sheets of paper under the front door. I set the pages there, some dog-eared, with tails tucked between their words, needing rest before being read and taken into anyone’s arms. The words met you with their paws raised in the air, their wet dog eyes glinting in the dark, smelling of the early summer rain. I hoped what was written in these pages would be with Robert for what lay ahead of him. I took one last look at the pool hall and hoped Robert wouldn’t feel so lost and understood that he belonged anywhere his feet could take him because his words together, on these pages, made a wailing sound as ancient and as familiar as the sea.

11

Insuk

Tacoma, 2000

Four years ago, after Huran’s funeral, Sungho chatted me up after work with conversation he usually saved for his mother. Sungho must’ve been curious about how we could’ve grown apart. I could see that Sungho had been a bird caught in a trap all these years and, struggling wildly, had broken his own wings. It wasn’t long after Huran passed that Sungho and I were able to meet as if for the second time. I thought of what he had wanted from his mother and mirrored the ways she consoled him. I prepared misugaru shakes in the mornings and herbal soups in the evenings. Pressed the point between his thumb and index finger for headaches. Filled a bath to cast some relief for his senses. I stopped looking for Robert. Though he must’ve looked for me, as if I might appear like paper before his pen.

Sungho used a softer voice with me than before. He opened the dry cleaners in Irvington. The cleaners was steady. “During a war, the cleaners will stay open like a church,” he said, “because it helps people feel clean.” Four years later, when Sungho put the cleaners up for sale, bids were coming in high, and he asked me what I wanted to do. “People are drowning in hospital bills because of their aging parents,” he said. “My mother gave us a gift—leaving so quickly. She was always a tidy person.” Sungho spoke frankly, in a way he never would have if Huran were alive. We stopped going to church. Mass had gaps in the pews, new families came. The seats felt cold, hard. Children in the room with the glass window cried in a flock. I made no effort to think up an excuse for walking out after Eucharist.

“What’s keeping us here?” I asked him.

Sungho didn’t dismiss my thoughts as he used to.

“I know it’s been unbearable for you,” he said. “You’ve done enough for us.” It was the closest to an apology I’d heard from him. His neck curved toward me in a light that opened like a cataract. Without Huran, I began to feel as if my time with her and Sungho might’ve been nothing but a nightmare.

“Do you want to move up north?” he asked.

“We can start over somewhere it rains.”

“Tell me where to go, Insuk.” Then he brought his hand up to his mouth. “I just don’t know anymore.” Looking at Sungho, it seemed as if his bones had a lightness to them like a cricket, and he raised his wings, striking the sound of what could be the first of many right decisions he would make for us both.

~

Sungho was forty-three when I found a rotten tooth.

Sungho leaned in to kiss me at the door, and a stench came from his mouth. The inside looked like one house with all its lights off. A tooth cost two hundred dollars; a temporary one cost sixty. There were years we didn’t have sixty dollars. On the way to the dentist I asked him, “Why didn’t you tell me about your tooth?”

Oak trees reflected on the windshield.

“It’s not a problem,” he said.

“Your mother hated stinky breath.”

“Did she?” Sungho stared out the window of the passenger seat. “I don’t think she ever told me.”

“Your mother hated the smell of pork. I had to clean and boil it three times. Twice wasn’t enough.” I relaxed my grip on the wheel—I’d known Huran better than anyone.

“You sound just like her.”

“How did you ignore it? The worst pain,” and I showed him three fingers, “comes from your eyes, mouth, and crotch. You can’t do anything but lie there.”

“I just lived with it,” and he grinned. “Like I do with you.”

When I parked in the lot, the sun was on its descent between the buildings. “Stop joking around,” I said. “Tell me what’s going on, Sungho.”

“I wasn’t letting my tooth fester. I was making friends with it.” Sungho refrained from speaking further because of his stinking mouth.

“I probably would’ve never known until they found an infection inside your skull.”

Sungho followed my footsteps over the asphalt, porous like black coals. His tongue poked around his mouth.

“Your tooth,” I said. “We’re taking it out today.”

“We can’t save it?”

“You want to keep your infected tooth?”

“It wasn’t infected until a few days ago. It’s a part of me, you know,” he said. “It’s natural to feel this way.”

My laughter caught me by surprise.

“The worst pain comes from your heart.” He put a fist over his chest. “I’m lonely—I think I need driving lessons. Can you be my driving instructor?”

I slapped his arm lightly. “Are you flirting with me? Lucky for you, your mother wouldn’t let anyone get between us but herself. Especially no driving instructor.”

Sungho paused at the door. “If we do leave, you think Henry will come with us?”

“Love goes in one direction,” I said. “Parents love their children more than their children possibly can.”

Sungho puffed his chest. “If he doesn’t want to come, at least he doesn’t have a gaping hole in his tooth!”

“Fine,” I said. “He’s a little better off than you.” I took Sungho inside, both of us bowing before the door closed behind us.

It must’ve been during college, walking along the riverbank, when we last spoke so openly with each other, as if we no longer had to speak through the gauze we’d wrapped over our faces these past years. That night I did something I’d never done before and opened my purse and bought Sungho a shiny gold tooth.

~

In the spring, I set out a plate of yellow-ringed melon, and the movers popped the slices into their mouths. When I remarked what few things I owned in the end, they told me how people brought nothing into this life and took nothing when they left. They drove from Tacoma back to California, like whales leaving for another ocean. A port city along Washington’s Puget Sound, fifty miles from Mount Rainier, Tacoma powered heavy-duty trucks, ships, and trains. The smell of sulfur came from the tideflats, the mills and refineries. Museums opened downtown, and storefronts had signs up for leasing. Newly paved roads had white paint, like gleaming bones in an X-ray.

The house was two stories with three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a garage, and a sloping lawn. To gather light, I hung mirrors on the walls; Sungho added shadows—an antique clock, a leather recliner, and a dark ottoman. I felt sorry about how I thought so little of Henry when I was with Sungho. Unlike your child, your husband stayed under your care. Most days were occupied by Sungho’s shoulders, the corner of his mouth, rising and falling, and the impact of his footsteps on the stairs. Sungho looked past the vaulted ceiling, at some clot of darkness, and asked the question that was most on his mind these days: “You think Henry will come? Where do you think he goes?”

I smiled at Sungho through the arched mirror by the doorway. Mirrors tended to exaggerate smiles. “Henry’s favorite thing in the world,” I said, “is the world.”

Sungho settled into his recliner, keeping the remote in hand. “It’s like watching my father as a boy growing up to become himself,” he said. “And I can’t do anything about it.”

The TV interrupted us. Multiple news stations reported an inter-Korean summit. Leaders of the two Koreas had met for the first time since the armistice. They had declared plans for two provinces in a united Korea with a central authority.

Sungho switched it off.

“What’re you doing?” I asked.

“Let’s go for a swim.”

“It was important, Sungho.”

Sungho approached me, and when I pushed him away, his laughter came from across the room. “Let’s go for a swim.”

“Fine,” I said. “I could go for a swim.” His palm followed the rail as he went upstairs. I heard him rummaging through a box.

Sungho dangled swim shorts over the banister. “It’s a white flag,” and he waved his shorts. “Do you see it?”

“That’s just ugly—you’re ugly.”

“Every sock has a pair, no matter how ugly!”

I accused Sungho of changing into a playful person now that we’d moved into a house perched atop a hill. The first floor of the townhome lay beneath the ground at a dip in the road. As we moved aboveground, a part of Sungho was unearthed.

Sungho came downstairs and took my hand. He ran my knuckles against his stubble, sizzling like jeon in the pan. “It tickles, you idiot,” and I pushed him again.

We recognized after twenty years the thrill in our chests as we chased and groped our way through the rooms of the house. We refused to hear reason and toppled the sofa and the recliner, running and giggling in the air as thick as makgeolli, as if we were rushing after our tied-up beer cans that had broken loose on the rocks and drifted down the river, but that was a long time ago, and now it was just us, in the hours passing smoothly like flour through a sifter, and the woolly bushes tapping against our windows, and there was his one golden tooth shining a single narrow path in my direction.

~

Pushing through the doors, we left the house together, walking down the road on careful feet. Shorts and swimsuit in hand. Our shadows deepened by rooflines overhead. We followed the streetlamps, the smeared silvery light. We matched our pace, the only people on the slope toward the beach. We huddled together despite the warmth of the night and the width of the pathway, leaving no space between us as we headed down the steep hill. “You remind me of somebody,” I said.

Sungho raised an eyebrow. “Is that so?”

“A sweet boy I met a long time ago.”

“What was he like?”

“Well, he was a nice boy.”

“Are you sure?”

“He was tall and handsome.”

“He does sound familiar.”

“What’re you doing in a place like this?”

“I’m looking for a nice girl.”

“Is that right—for how long?”

“Two decades, maybe.”

“I was here on the beach,” I said.

“We must’ve just missed each other.”

Sungho’s hands wandered under my shirt.

“I thought you were a nice boy.”

“I’m a very nice boy,” he said.

Sungho led me with urgency to where we heard the trees, the waves. Overhead, the crows appeared as if they were sliding down an invisible wire. A heron stood on a post above the beach. No one was on the coastline. We stripped and bore the wind and its cursive around us. We stepped into the water, waded past the dock, and we floated apart, not saying a word, then worked our way back, welding the space between us, staring at the deep blue soaking the beams, the sand, our bodies. He lifted me in the water, and my legs circled his middle, drawing him closer.

As the lights on the distant islands went out, whole cities seemed to float away. Like moths that lit up when they fluttered into a fire—death must light us up for God to notice. The deeper water filled me with guilt as I came to see how it could’ve been that, for years, I wouldn’t help Sungho without the reminder he was less than me, and meanwhile, Sungho must have been longing for me all the same. I pulled back to take a breath. The way he pressed himself into my belly and against my hips—his face sharp with yearning. All those years, I must have believed Sungho was cruel, but when left alone, his joy was larger than my body.

12

Jennie

San Jose, 2000

Things had changed and Jennie had known it was coming. The sun could barely touch the horizon and yet considering all that happened—could it only have been three weeks? Her muscles tore through their husks, and she felt the ache of her dry throat and angry breasts, their webbed veins, her swollen ankles impossible to fold, her belly hardened with what she tried to understand. Every night the baby breathed underwater, curled up in the whorl of a mollusk, stealing the plums and apricots she craved, until she passed out in a slumber, trapped in halogen nightmares. Jennie woke up to her head splitting like a raw egg in a condor’s claws. It was during one of those days her arms and legs throbbed as if they were tearing apart. But swimming in the lagoon, crowding inside her van, brawling on the sand. The whole time Jennie was falling in love. Revisiting that day with Henry sent the same chills through her. When he shook his hair out, the strands caught in the sweep of autumn wind. Jennie was twenty when at last the baby showed its smooth honey face.

~

After the night at the lagoon, Jennie found him, midday, leaning against his bike on the racks after coming back with a duffel bag of his things at his feet. Jennie led him to her electric-green van parked on the turnout. Henry’s voice followed her to the door. “You live here alone?” She nodded, and said no one had seen it before. Henry hopped onto the foldout steps and skipped ahead of her, like a hummingbird just out of reach. The van was spacious inside. She had converted it into a study and kitchen that folded into the walls, with extendable bar tops on metal arms. Tucking the LEDs, she revealed a woodblock counter and, underneath it, a rolling cabinet fridge. The bodywork of the outfitted interior swiveled around her, jolting close and away, thrumming with essentials, anchored as an ecosystem of interlocking parts built over years. How she navigated the inside must have intrigued him.

Jennie retrieved a plastic jug of cold broth. Poured it into two stainless steel bowls off the dish rack in the overhead storage. Sound rushed from the propane system.

She put on boiling water, added thin noodles. On a makeshift board, she chopped cucumber and pear, peeled boiled eggs.

Jennie shrugged off his hands. “How long are you staying?”

Henry sat on the bench. “For a while—if you want.”

She heard him say he’d leave one of these days. “For a while?” she asked. “Won’t your parents look for you?”

Tossing his duffel onto the seat, he was unpacked. “My mother doesn’t look for anyone but my father. It’s a good thing,” and he pointed his chin at the board. “Is that mulnaengmyeon?”

Jennie wiped the bowls with a dishrag. She betrayed no more signs of concern and showed her excitement. “This broth will shoot straight up your meridian.”

After a dip in the boiling water, the potato-starch noodles were rinsed under the faucet. Fistfuls she twirled like hair and dropped into the bowls, splashing the broth over the steel sides. Making light work, she arranged the toppings.

“Tell me what you think,” she said.

Mulnaengmyeon was a North Korean specialty. Siberian weather and mountains suited root vegetables. Those who’d fled during the war packed their taste for cold noodles, then whipped the horses and oxen to start. The delicacy was served in steel bowls with a tangy iced broth, topped with ribbons of cucumber, radish, sweet pear, a well-boiled egg, and noodles so long their lives couldn’t be cut short. Jennie thought of it whenever she sprawled on the summer grass.

Henry picked up the bowl in his palms and slurped, using the chopsticks to tow the noodles and toppings into his mouth.

On his face was a keen joy, accompanied by a shudder—his head tipped back to down the rest of the broth.

Jennie set her empty bowl on the counter.

He breathed deep into his lungs. “It’s sweet.”

“Morioka reimen.” North Korean refugees had fled to Morioka in Japan and opened mulnaengmyeon shops. “We were too poor for mulnaengmyeon in the North,” she said. “So I didn’t know mulnaengmyeon had sugar. They leave it out in the South. But the funny thing is the sugar stayed in Japan. The Japanese cooks at Yaohan showed me.”

“My father complains that Japanese food is too sweet,” he said. “But mulnaengmyeon is sweet.”

“First time I had mulnaengmyeon the way it’s supposed to taste was right here in the US—the place I learned about through stereotypes. Don’t go near a mall, everybody shoots each other, multiple wives, Bible-thumping fanatics—but a consensus that—the world would be hell without American rock music.”

Jennie rolled the refrigerator in and slid the desktop over the counter. Pulled in the screens, fixed the hinges. Tapped a monitor to her left. She enlarged the Korean peninsula. “You Koreans call a Korean person a Han-in,” then she gestured to the North. “But I grew up a Joseon-in. Joseon was the last kingdom on the peninsula before the Japanese.” She centered the border between the Koreas. “From here down, you use Korean words adapted from English because of Americans. We don’t do that. The North preserves our Korean. It’s why a North Korean never wonders whether they’re Korean.”

Henry pointed to himself: “Han-in.”

“Joseon-in.”

For the Korean language, he said: “Hangeul.”

“Joseongeul.”

“There’s an elegance to it.”

“All this is to say—Robert wants this feeling most of all,” she said. “Someone like Robert is obsessed with being seen as himself and without question.”

Henry frowned at his steel bowl.

“Robert knows his options. Nukes and assassinations are out. Invasions are dangerous. Puppet leader is gone. North Korean spring is slow. He needs a South Korean spring,” she said. “You saw his flag of the whole peninsula. But a flag like that doesn’t change what happened—it erases what happened.” Jennie tapped the ringing bowls. “This is something new. Something we haven’t seen before. And it doesn’t erase the past. It keeps the past with us as we go forward.”

Morioka reimen summoned for Jennie what she imagined as the cocoon taste of the world she had left behind, like the wallpaper of hand-drawn flowers at her apartment outside Pyongyang, coated with a patina throughout the years. The apartment and its wallpaper conjured the carrel of lives that passed through, and the sharp taste inside the steel bowl reflected an impossible condition of life, when all that toughness and suspicion had come down on her so young that she had little memory of her childhood, except how one can cry from a thousand eyes, how in the midst of human destruction, full-toned voices broke into song, each of them apart from and a part of longing and hesitation and indignation, roiling to an intensity of hope.

Henry closed his eyes. “What about—beautiful?”

“You mean the word?”

“Areumdaweo.”

Jennie, standing over him, traced the characters for areumdaweo on the crown of his head. The shapes resembled a lake, a fire, a house, and a person. “Henry-ya,” she said, “the word for beautiful is always the same.”

~

Jennie was feeling nauseous and couldn’t recall the last time she had felt sick. When Henry asked her what she thought about living together in the van, she smiled to encourage him. Henry must’ve not been aware of her condition because he asked again, and she was careful to say nothing. Actually she was sure he didn’t know because he wandered the lagoon in a daze. Though she liked the van and the feelings that came with it, she stepped out to loosen her body. Time slowed, the hours throttled back. The sun was high. Armadillo-skinned palms dropped pods onto the windshields of parked cars. Baby palms like feather dusters stood along the asphalt where crows mowed the road for scraps.

Jennie asked whether he planned on going to college, and he rubbed his hands as if to light her question on fire. She couldn’t tell what he was thinking. For some reason, she had a feeling he would wander too far—yet it was his slippery nature, like a minnow in the water, that drew her to him. When she asked too many questions, Henry would seat her on the handlebars of his bike, between his arms, and coast along Stevens Creek. Laughter pitched them forward. Either his wheels were going or his mind was going, and there was no middle point. At eighteen, it was for pleasure that Henry carved a path all over the city, his silhouette lurching through stark hills and long-haired ferns, yielding to soft mudslides.

Jennie moved the van closer to shore. She gripped the wheel with her nails. She put on the radio and hurtled through the local stations. The rearview mirror, a square sun on the dash. They passed a row of metal-plated awnings. Jennie excused herself and walked to a portable toilet. She pushed her stomach, forced the food out. Whole afternoons she ached from her toes up. Her throat felt scorched. As she walked with Henry toward the water, she realized how close they’d become. She couldn’t imagine trying to hold on to him, or ridding herself of the baby. She picked up her thoughts and didn’t set them down again. “If you have to go,” Jennie said, “at least tell me about them.”

Henry slipped into the surf. “My parents? They’d like you more than they like me,” he said. “After living here so long, they like anybody but South Koreans.”

This gave the impression his parents were losing their minds, but Jennie nodded. “I like them already,” she said, watching him floating on the lagoon. “With you from the South and me from the North, what does that make us?”

The waves broke and frothed the air.

Henry took long strides out of the water toward her. “Mulnaengmyeon.”

“With sugar,” she said.

When it was dark, they huddled in a sleeping bag on the sand. They watched the moon ripen. It was prolonged in a clear sky. There was no sound at first. But his breathing became shallow. When she turned, his hand was a shadow above her waist. Jennie felt the gap between them close, and her touch became desperate, her arousal a balm for her nausea. Henry seemed so willing to disappear, like he didn’t mind being no one or nothing at all. He was free above all from himself. The long night stretched its legs into dawn. Ants crossed the grains in their miniature life. The ochre light left braids in his hair. Jennie peered over as he fell asleep, his face a rumpled patch of grass.

~

At first light Jennie called him into the van. She took the bench while he stood at the door. Jennie told him to watch the screen.

The news broke that some time ago the Korean leaders had met at an inter-Korean summit. Separated families had been reunited in Pyongyang and Seoul. Topics on the agenda included ending the war and reunification. The news focused on a second historic event—the leaders supposedly had bowls of mulnaengmyeon, separately or together. Across the country long lines of people were waiting at mulnaengmyeon restaurants. Thousands had closed after running out of ingredients. Grocery stores had sold out of noodles. People were hawking radishes outside the stations. There was a newfound hunger for peace.

Henry had chopsticks in his right hand, twirled noodles as shiny as vinyl and dragged them into his mouth.

“My dad talks about a place inside where no one can reach you. I just thought he sounded like a lonely man.” He pointed at the screen. “But it’s the opposite. I think it’s a real place he’s talking about—back home where he grew up.”

“Of course,” Jennie said, “Even the bleak architecture from the North still feels like home. My parents told me when I was a kid that if the country ever reunited, they’d never go South, there was nothing there for them, and they were right. Those reporters, those people don’t know. They can open the border, but it’ll still be there.”

Henry dumped his bowl in the sink.

Jennie said to him, “You’re running away, aren’t you?” She couldn’t stop him from going, and he couldn’t keep himself here. Henry grabbed the pitcher of broth out of the fridge. He chugged it and chucked it over his shoulder. Joy shattered across his face in slow-motion like a windowpane, and she didn’t know, until now, that she needed to see it. The sun hit Henry’s skin like it did the water, passing through him, but left changed on the other side.

“I’m going home,” he said. “Come with me, Jennie.”

13

Tomoko

San Francisco, 2001

Tomoko, a ticket agent at San Francisco International Airport, dealt with her hallucinations by identifying them on her phone. At a young age, she learned that a person she hallucinated didn’t transfer onto a device. For her job interview, Tomoko had talked to an agent for thirty minutes before she checked her phone for the first time and opened the camera, where the interviewer’s image couldn’t be seen. When the actual interview began, she had practiced enough to not suggest she had any problems. Tomoko worked the counter since she could keep her computer camera on to tell whether people and things approaching her lane were in her mind, or in reality. So when Tomoko spotted the man who matched the description on her watch list, she waved him to her lane, where the fortysomething in a gray suit with a messenger bag appeared clearly on her screen. She glanced up from his passport.

“You’re quite handsome,” she said, and he was, despite the harsh penalty listed under his name.

Robert seemed to consider her. Tomoko was simple-looking with a raindrop face. “Is that so?” and he set his bag down. “Thought I’d make it to the gate at least.”

“Looks like your first trip back to Korea,” and Tomoko read to him: “You’ve been flagged as reasonably suspected to be, or have been, engaged, preparing for, or aiding in work as articulable as a potential risk or threat to national security.”

“I can be a terror,” he said, “but I’m no terrorist.”

“That’s pretty funny,” and she smiled. “They should’ve put that in here. There’s some good news.”

“What could possibly be good about this?”

“I bet you didn’t know anyone cared about you.”

Robert grinned and told her it was inappropriate to flirt with a terrorist—a word she corrected to a fraud.

Tomoko stayed behind the counter with her finger over the call button for the security guards. Two guards stood nearby. “Your current resident status has been terminated, and you’re being deported for crimes of moral turpitude.”

On her screen, Robert asked, “For my newspaper?”

His real question was: Would he survive? But a question whose answer depended on chance was not worth asking at all.

“Security will escort you to your gate.”

“And what do you think waits for me in Korea?”

“They’ll transfer you to a prison is my guess.”

Tomoko found no reason to partake in his reality. Her awareness, and not her ignorance, put her in a furnace of indifference. Who did he expect her to be, this woman at the airline counter with a smile? He couldn’t recognize Tomoko apart from his own imaginings. She wasn’t a CIA agent, a salesman, a spy, or a person with ideals. Tomoko was a ticket agent, that was all.

Robert unbuttoned his suit jacket, stared at Tomoko, and said, “I’ve been invited to speak at the Busan convention hall. I must qualify for humanitarian work travel.”

“You don’t qualify for immunity.”

“I won’t go to prison for this.”

Without warning, Robert reached across and grabbed her. He flung Tomoko over the counter and dropped her on her side.

She heard him break for the moving walkway.

Tomoko’s head pounded. She didn’t feel she was in any danger, only surprised. When she pulled herself up to the counter, she used her computer to watch the whole thing. Tomoko understood nothing was true if it could not accompany something that showed on a device.

Two agents tackled Robert before he could touch the moving walkway, its rubber belt sliding over metal rollers that groaned underfoot, onlookers, connecting between terminals or lugging bags across concourses, stopping to watch, crowding him, visibly stimulated by his head smashing into the floor, the man muffled but wriggling and warbling, his complexion pale, his body wrangled up, his arms cuffed behind him, and the way he flung his dreams into the air, called the name of a woman, his mother or his lover, until the stun guns came out, and their bright silver mandibles clicked into place, making a gourd-shaped stain on his pants.

Mouth slack, he was trying to button his suit closed, but his arms wouldn’t reach, so he shouted that he wished to button his suit, then begged for somebody to do it, and even then he was handsome, the dark furrows of his brows, the bridge of his nose, and from farther away came the booted footsteps of police, bins knocked over, the airport vehicle brakes screeching, their radios bleating, yellow tape on the tarmac. Tomoko watched her blank reflection on the screen, grinding her teeth as she did in her sleep, her fingers pressing into her brain, synapses branching, thrumming, spinning as she counted the people who stopped to watch the handsome man, not a hundred, or even a thousand, but more like one zero zero zero zero zero zero.

Robert

Robert arrived at the western end of the demilitarized zone, the border between North and South Korea, one hundred sixty miles long and two and a half miles wide while morning mist still guarded the watchtowers. Robert had lived to smell the tidal marshes, rich and damp off the rains from the monsoon season. A red-crowned crane, early for winter, stood idly as if on a wall screen or a celadon vase in a museum. They had put him on a civilian plane, a cargo train, then an armored vehicle, and after a day and a half, Robert was looking at farmlands. He had only heard rumors of political prisoners who were interned in farming villages surrounded by barbed-wire fences.

Hours after his arrival, the South Korean guards escorted Robert off the farmlands and across torqued wires to the border station and its baby blue meeting rooms. When he stumbled on a craggy incline, the guards fixed his shoelaces. And when he looked out from the trail, the guards paused for him. A wildlife refuge naturally sprang from a place without humans. The flora and fauna rooted themselves in the primordial land. But within miles, armies on both sides could bombard each other at ten thousand rounds a minute. The guards let him inside a meeting room. They popped the cuffs off him, ignoring security measures, and went out, locking the door behind them.

When it opened again, the first guard, who towered above him, appeared, folding away an application to gain entry. The second guard, with sunburned cheeks, rolled in a utility cart with equipment covered by a black tarp. The equipment would’ve arrived by train crossing the Imjin and been transferred onto a bus to the civilian-restricted area. The first guard asked the second guard why they shouldn’t have a little fun, and the second guard said why not. They parked the mysterious equipment against the wall and left the room.

Robert’s attention went to the warm, lined corner where he could sleep. He recalled that his mother and father shared their names with their countrymen just as those across the border, outside his windows, shared their names with him. Robert remembered events by their years, and bodies by their numbers. When he counted these things together, the sum amounted to nothing but a haze. It could be that all memory of Korea came from the border, and the farther you were from the border, the more your memory faded like a coyote who looked back just once before running off into the forest.

~

At a gravelly, scraping sound, the door shoved open by a wild boar that walked into the room sniffing the floor. Muscles tight, Robert shot up. He was certain the boar weighed more than him. Layers of black-brown hair, upright ears, reddish around its trotters and snout. Stench of garbage like the wild boars on Jeju Island, which had often roamed in packs and damaged crops when he was a boy. The boar tugged off the tarp, revealing not just any equipment but arms for the Republic of Korea Army.

Robert knew what he was looking at, more or less, but these were new models. There was an assault rifle, a machine gun, and a pistol, and the fourth was also a machine gun using an advanced system. The assault rifle and the first machine gun were familiar from his time in the army, but the pistol and the second machine gun had lighter, solid frames with matte finishes. The boar poked around. Its snout moved independently of its face. Robert scrambled to the far corner, where he stood as the third point of a triangle formed by the boar, the arms, and himself.

Robert turned the situation over in his mind. The guards could be asking Robert to shoot the boar. They might want to see if he could use the arms. They might want to see what he would do before deciding what to do with him. They had left no instructions. Perhaps they feared how Robert would react if he were to be liberated. What if he sought vengeance? How could they measure his desperation? When Robert arrived in his own country, he had stepped onto enemy territory. Many people had taunted him for coming back home. The dust, swirling under the waning sun, settled onto his eyelashes.

~

When the two guards appeared again, they ignored him and the tarp, and crossed the room to the boar. Then the guards were on their knees, scratching the boar’s belly, cooing in gentle tones. They brushed its long-haired chin and tasseled legs. The first guard took a fistful of beans out of his pack and fed the boar. As the boar grunted and spat, the second guard tried an impersonation but was scolded by the first guard for insulting the boar as it was eating—a cause for indigestion. The second guard nestled his nose into the boar’s side as it munched ripe beans off his palm. The guards fussed over its crusted eyes, its brittle canines, asking after its well-being, to which it replied by sniffing their packs.

The second guard handed Robert a change of clothes and lured the boar outside, where they waited for him.

The guards had left him again with the military equipment.

Robert dressed quickly and came out, squinting at the midday sun. He followed the guards’ footsteps and the boar’s moonsteps to the ridge, where he could see in the distance a husband and wife and three children touring the grounds. The border had a strict dress code, but the family wore tattered jeans and sweaters. The North often captured footage of tourists in torn apparel as propaganda to show the South’s failings. The guards, however, waved to the tourists jovially. The guards explained that times were changing and that the family’s attire had government approval.

Robert, the guards, and the boar arrived at a field.

The first guard, staring at the field’s edge, said, “Can we call you Rob?” The name fell easily out of his mouth.

The second guard stood a few strides away, showing regard for Robert’s space. “Even all the way here at the DMZ, we’ve heard of you.”

Robert was surprised when told of the distance his words had traveled, holding him to some esteem.

The field was overgrown—soft if he were to kneel in it. “The guns are for me,” Robert said. “I was suspicious, but I figured it was true when you left me in the room to change this morning.”

Robert went on, “At the start, I thought I was supposed to shoot the boar,” and this made the guards chuckle. “The boar is your pet that just happened to wander in. You never planned for the boar. You treat it too well to let me shoot it.”

The first guard brushed the boar’s ears. “Isn’t that so?”

“No mistakes so far,” the second guard said.

“You put guns in the room to see if I’d run. When I didn’t run, you agreed on something,” Robert said. “I could be a lure. I could lure people out when I announce my arrival.”

The second guard nodded. “I do believe in good timing.” His eyes shot up. “We want to help you. Your mission is nice and simple: Some dangerous people are bound to show at your lecture in Busan. Shoot one down, and you’re free to go.”

“No prison, no internment,” the first guard said.

“It can be anybody. The target is your choice,” the second guard said. “But you only catch a tiger by going into its cage.”

“What about me?” Robert asked. “Aren’t I dangerous?”

“Rob, you’re harmless.” The first guard spoke words Robert had never heard before. “You’re not a political figure, and you’re not that radical. You’re a revolutionary from the old days. But in this day and age, you’re a person with a conscience, that’s all.” The guard had lined up a cue stick and split a pyramid on a pool table, and each of Robert’s life choices clattered in every direction.

“You still make good points in your paper,” the second guard reassured Robert. “Don’t kick yourself over it. You’re going to be out of here. You do this, and it’ll squash any protestors and any doubt about you going free,” and he slapped his back. “And don’t worry about what happens. You just try your best, Rob.”

“You can choose a gift for the road,” the first guard said. “We make guns now. They’re indigenous. Daewoo Precision Industries K2 assault rifle—standard service rifle. Shoulder-fired, gas-operated. Fires both the .45 and .223.”

“We started design and development years ago,” the second guard said. “The K2 you see with the pistol grip and side-foldable buttstock? It goes semiauto, three-round, fully automatic.” He made a gesture for sewing his mouth closed. “We sell them to Cambodia, Ecuador, Fiji, Indonesia, Iraq, Lebanon, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, Philippines. North Korea’s even made dupes of them. What a compliment!”

“The K2 works fine, probably shocking for you to hear, but it does have an overheating problem,” the first guard said. “K3 is the light machine gun. They modernized it, underside rails, side-folding stock, carbon fiber shield. South Africa and Thailand like them. Asian arms manufacturers are finally getting ahead of Western ones.”

“Daewoo,” Robert said. “They make cars, don’t they?”

The second guard smirked. “Motor vehicles division’s big, but they oversee tanks and arms production. Military invents everything civilians use. The military budget funded the internet for the front lines. First mobile phones were used in the army. Things get made mostly by the companies you hear about, and they find their way back to the commercial market because civilians want to buy our cool shit.”

The second guard seemed composed until he came to the last two weapons in the series. “That pretty K5 you saw in there is a semiautomatic pistol. Compact, lightweight, fast-action trigger for accurate shots. And I mean accurate. The frame is forged from aluminum alloy, and it has a matte finish. The slide and barrel, forged from steel, with a right twist. On the market, Americans love it. They like the sexy look.” The second guard chuckled. “The K7 is my favorite. It’s our submachine gun with an integral suppressor. We got the idea from our special forces lot. Takes standard or subsonic ammo. Simple, clean blowback system. We finished it in December. Let’s just say people are going to shit themselves at the IDEX.”

The first guard rolled his eyes. “If you’re done touching yourself, we can get on with the show.”

The second guard said to Robert, “One body in the ground will do, but you should protect yourself. It’s your lecture, buddy.”

Across the field, they could see the North Korean guards pacing the border. The first guard said, “Looking at them is like looking into the past. Sometimes your past smiles at you. Other times your past points a gun at you.” The first guard went on in a firm voice, “Don’t get stuck in the old world. You’re waking up to the new one. We don’t do things like we used to. We’re not even the same people. You go out there and say what you’re going to say, and you’ll see. You’ll get treated worse than a dog,” and he shook his head. “The only people who understand you are right here, where you don’t want to look. We see, as clear as day, who you are. Because we are you, except we stayed back home. We don’t need any more businessmen or leaders,” he said. “What we need is a good man.”

14

Robert

Busan, 2001

The nation held its breath the following summer as the president of South Korea won the Nobel Peace Prize for his Sunshine Policy toward North Korea. Exiled and kidnapped, he’d protested the government and its dictatorial rule, issuing an antigovernment manifesto, and was locked up before being released two years later, designated a “prisoner of conscience” by Amnesty International. With a vocational high school education, he coolly won against an elite opponent with an advanced degree, and was elected into the Blue House, where he dawned the Sunshine Policy for the reunification of the Korean states. It recognized two different systems, militaries, and foreign policies, with relations to be managed by inter-Korean organizations until unification could bring about a federal system of one people, two regional governments. North Korea didn’t oppose the presence of US troops on the peninsula for protection, keeping China at bay. After the peace summit, during the Olympic ceremony, the Korean Unification Flag was trotted into the stadium. On a white flag, a blue silhouette of the Korean peninsula. The pale cloth flashed. Robert had waited decades for the flag to wave across LED screens at train stations and bars, markets and apartments. Everywhere people watched. They gazed at the flag the way you might gaze into the younger faces of your parents and recognize yourself.

~

After four days, the guards released Robert in an armored vehicle, and instead of sending him to a prison, they kept their word and put him on a bus headed south, and then a train to the city. Outside the station, Robert rented a car to drive farther south along the coast to Busan, following the dock houses and seafood markets. Over two hundred fifty miles later, Robert pulled up in front of the convention hall in Busan where he’d originally planned a lecture on his writings. His words from Liberation Shinmun had traveled to these shores, and the invitation by locals was something to be proud of. More than the prestige, the rarity of this conference was supposed to draw out a network of people who would spend an evening discussing his views. In front of the main auditorium, Robert could see journalists and news cameras, tipped off by protests against reunification that had taken place ahead of his arrival. Perhaps Robert wouldn’t motivate anyone, but he had to use what would be his last chance to speak to his countrymen. Sitting in the darkness of the car, Robert dreamed of an impossible evening in which common sense prevailed. However, instead of the many pages of his writings, Robert found in his bag a single loaded gun.

Jennie

Jennie drove the van north from San Jose past the townhomes of Milpitas and Ohlone College and through the valleys where stiff yellow grass could threaten smoke even in the cold. These days, Jennie couldn’t sleep, her hands clammy and blankets corkscrewed, or she jolted awake as if birds had tangled themselves inside her. There was a steeliness in her bones—all molars. Burning fuel, she snaked the highways. They stopped for burritos in the Mission District near the cemetery at an adobe-style restaurant. Behind the bar-top altar, old timber walls, hanging rawhide, a Spanish-style organ, a copper bell, a figure of Christ above, and, even higher than God’s son, a television that Henry flipped through with a remote. The Korean news came on. Faces distorted by the force of motion, their one-way gazes, protest signs heaved out of the frame. Jennie tore each day off like a sheet from a daily calendar, watching her days grow thinner, just as she watched the older generation disappear, taking with them their connection to the border. Jennie ordered two burritos and beers.

Robert

Standing in the wings of the main auditorium, Robert stared out at the reporters and journalists, students and locals, waiting in the crowd. His heart raced to see it was standing room only, even as the Mnet Music Video Festival ramped up back in Seoul with honey-voiced Jo Sungmo leading the nominees. Robert stepped onto the stage in his gray suit, which had few wrinkles because the guards had given him a change of clothes. Robert stood behind the center podium. Leaning forward, he scanned the auditorium. The guards were nowhere to be seen because they hadn’t followed him. The weather stopped at the door. Security checked into the pit. Crowds pushed onto the floor. Greetings shot across the aisles. Flash orbs had eyes like tree knots. Shadows flew up and shattered across the ceiling.

Robert looked out at hundreds of his countrymen. Through their cameras, thousands. Behind him a projection illumed a flag of the Korean peninsula. Clicks fired in the cavernous space. Light barreled toward him. Their lenses captured him, as if he were a common fly suspended inside of a glass jar. Robert noticed how tired he must be to sway from a slight breeze. So he began: “We watched colonial empires crumble here and around the world. And with them, the reprehensible beliefs that raised them. We grew up against the backdrop of war. A war as militant as it was ideological—and we’ve observed little difference between the ways we’ve approached war. Still, there has been progress in our small country and in our standing in the greater world. Yet it was when I left Korea that I was free to be Korean.”

Jennie

Jennie, watching the news at the bar in the Mission, caught a few seconds of a clip, and she could have sworn it was Robert. It was Robert’s voice, but he looked narrower, the main light source above him throwing his shadows left and right. Henry jerked out of his seat. He was still in his swim shorts, despite the chilly air, his head sinking as he leaned over the bar. Hearing Robert’s words rather than seeing them on a page, she found some sense in them. Jennie could feel the heat radiating from the screen, like a corpse burning on temple grounds. Jennie popped the burrito from its aluminum seal. A shot of the audience showed faces dusted by stage glow. Black eyes, swallowing light. Bent arms, or camera props. Jennie couldn’t stop from gorging on the flesh of the tortilla. As if under the husk was her salvation, retrieved not with guns and knives but with teeth. Smiling, laughing, she slapped the bar top and broke into a howl.

Robert

The audience clapped. Those in seats or standing in aisles chuckled, and they wouldn’t have if they knew what Robert was going to say. He pawed the wrist that had been bothering him since the airport.

“The South Korea and Japan match at the 1997 World Cup qualifier—in Tokyo of all places,” and hoots came from the auditorium. “That’s right. Early in the second, Japan chipped the ball over Korea’s keeper. We thought it was over. Japan only had to protect their lead. But Korea scored a corner with a header. Now we’re a moral 1–1. Time’s running out. Suddenly, Korea fires a left footer into the back of the net.” Robert’s arms shot up, cheers erupted. “It’s called the Greatest Battle in Tokyo. It’s just a soccer game—a fucking game. My God, we lost so badly after that game, but who cares. For a moment, everybody was Korean. You were Korean because of your love for humans everywhere.”

Robert glanced at the projection. “For one day, this was our flag. Nobody saw a line,” he said. “Maybe I’m a fool. Why visit the past, why go digging up its grave? Why puncture a sense of safety we’ve carefully built for ourselves? Why not go on toward the things we know we can keep? We know what a home feels like and we can have one. We know what a family feels like and we can make one.” Robert thought of that night at the pool hall. It could be that Sungho believed freedom was only an idea, and an idea didn’t keep you alive. Yet they each had the freedom to choose their own way of seeing the world.

His voice reached the doors. “We remember the US picked a line at the thirty-eighth parallel, dividing Korea in half. North to the Soviets, South to the US. Millions of innocents dead in the war. Our problems since the border went up are growing. You know it, without me telling you tonight. The era we live in now deepens inequalities within and between nations. The consequences are landing on ordinary people and causing further divisions in wealth and policies as we grapple with discrimination, tribal nationalism, and greed.”

The projection behind him changed to photographs of protesters and political prisoners stuffed by groups of ten into twenty-five-square-foot cells. It was how he pictured Ominato in northern Japan before the Ukishima Maru detoured into the harbor. “Looking back we now know the opportunities we’ve lost. Fear-driven complacency. Brittle corruption. We are making the very mistakes we’ve long condemned.”

Robert motioned at a series of photographs from settlements under barbed wire manned by the country’s soldiers. He wasn’t among them. “These are the ominous parts of modernization and globalization,” Robert said with a humorless grin. “Nothing works better than hatred and fear, which are, as you well know, trending and on the rise, stirring national and global competition for power. Don’t let me tell you, you can see it for yourself.” Looking out at the faces, floating in the dark, the figure of Medusa occurred to him—a head of snakes. Medusa avoided mirrors to keep from turning herself into stone. Robert understood how Medusa was a fearless foe. How she was fearful above all of her own image.

Robert raised his face to the cool light of the projector. “In some ways we freed ourselves only to imprison others. As humankind, we agreed freedom is a resource with a controlled, limited supply.”

~

The Sunshine Policy was lost in the end. There were allegations that hundreds of millions of dollars had been paid to North Korea to secure the North-South peace summit. Hyundai had transferred five hundred million dollars to the North. Critics claimed that the president had bought his Nobel Peace Prize. Hyundai testified that they’d paid for business rights in the North. They were charged anyway with violating laws on foreign trade and inter-Korean affairs. The Hyundai chairman would apologize, jowls trembling at a televised news conference. US relations with the South became strained, as if the US were scolding its lesser sibling. Future summits were deemed tainted by the financial transaction. The president’s campaign, the inter-Korean summit, and the mulnaengmyeon tradition, all of it seemed like some orchestration, a performance. Few asked whether peace demanded a price. Fewer still pointed out that the policy’s problem lay not with the scandal but with its purpose. The policy aided the North without improving human rights in the North. There was a misunderstanding that North Korean people starved because they needed aid. They starved because they were in need of freedom.

When nationwide suspicions about spies and sympathizers for the North had reached a crescendo, the guards had rubbed Robert’s shoulders. The guards and Robert had shot the guns in the fields together. Robert could shoot into the auditorium, like he had in those fields, motivated by “conscience,” and be pardoned by the government. They would give him an apartment hoisted on government land on the Seoul outskirts where he could live in heavy clothes, shod in thick boots, stomping in the snow in the winter, or running along the river in the spring, summer, and fall. Robert would write letters to Insuk about how he could see the gleaming lights of two countries. On the auditorium stage, Robert slowed his speech—his head lolled. Whether peace or war, the same or a different outcome, it didn’t matter. But a still, small voice inside him seemed poised at this hour. That Jo Sungmo had won the music awards was the last thing Robert heard from the whispering crowd before he looked at the far booth into the camera’s shining red light.

~

By the time the projector showed the fourth photograph, the Gwangju protests, there was silence. Some murmurs. Discontent. Reporters and journalists took in the view. Five in the aisles and four in the rows walked out. Notepads were folded away, repurposed as fans. Media cycles wouldn’t run this story. Now it was a spectacle. The people who stayed glanced sideways.

Robert wasn’t asking them to abandon their lives. He was asking them for three minutes on stage.

Coughs. Someone laughed for the hell of it.

Two minutes in, he gripped his hurt wrist.

“For the moment we’ve lost sight of a cause to unite us.” Robert needed to make them question the war and the border, and their own biases.

Robert couldn’t speak in a rush, or it would all be for nothing. “I’m going to ask you a question.”

Nervous laughs, a sole clap. It wasn’t that Robert was articulate, but there was a satisfying element in hearing his argument fill the strange vase he presented.

The projection lit up the flag.

“I’m asking you if a divided country is still a country.”

Robert turned from the crowd, crossed the stage, then made his way back, as if going through the fields of tall grass waving in his path, feet tangled in wildflowers like umbrellas unfolding, red camellias rustling, animals grazing nearby, a rippling stream ahead, a tucked-away bank, but nothing in the distance. Not his mother waiting for him, no floating debris. Nothing of Insuk’s beauty through the glass door. Now of all times, he walked into the memory of an argument, when he was telling Insuk that if your leg was broken, you wouldn’t cut it off, would you, you’d care for it. That’s why a person, or a nation, couldn’t cut itself off. Behind him was the landscape of men and women, black-eyed, muscular and tight-skinned, dead in one long breath, each having left someone unloved.

Henry

I heard water in my ears before I saw the bridge. I took the wheel once we crossed the strait. Off the 680, the 80 east of Auburn bisected the Tahoe National Forest. The windows I opened for the sweet pine and balmy cedar, aromatic lakes, granite, and sky. Inside the van—the deep smell of jjajangmyeon, sharp mulnaengmyeon, lagoon sand eddying in whirls, flying over the road. I thought of Robert in the private rooms of Biwon. He had talked about different kinds of losses. That those losses must be imagined to make an apology. Because an apology must also mourn a future where those losses never occurred. Robert’s responsibility toward the world was not imaginary but as real and as defined as the brass fixtures of the pool hall, molded by the weight of history.

I crossed into Reno to keep east on the northbound road. By the time I looked out at Oregon, it was dark. Rain fed the mountain gulches. Mugwort in silver green. My shorts so damp I had to peel them off. I switched places with Jennie, who put a wet towel on her head. She drove seven hours through the night over the Columbia River and into Washington and then Tacoma. We covered the five kingdoms: the mineral, the vegetable, the animal, the human, and we must’ve passed a God between San Jose and Tacoma. By morning, the streets were dense with cars and music. Century-old brick warehouses. A rack of clothes for sale. Smashed box of cigarettes by the storm drain. Crowds appeared, moved like weather. A biker zoomed by, strips on his spokes blinking red.

Robert

“I consider it despicable.” Robert stopped, winding his two fingers like blades on a waterwheel. “To use our suffering to justify our destructive actions. I won’t be coerced into silence. It is precisely because I know what it is like to suffer that I will not be intimidated.” He paused, and said, “If you don’t feel moved by the horrors that have destroyed our past, then we are doomed in all our efforts toward the future.”

One reporter said, “The idea’s already been canceled and discarded by Koreans.”

Another reporter agreed. “Reunification is over,” he said. “It’s not a viable option.”

The crowd sounded far away. Outside, traffic had thinned from a standstill. Busan moved freely at ten at night. The technicians were on standby. A shrill pitch came from the speakers. Junior reporters and journalists recorded on their phones. They inched out of their seats and toward the stage.

“It’d cause innumerable deaths,” a third reporter said.

Robert’s shoes remained fixed to the floor. “The border is sustained by us. We choose it every day. It is a fact that we can’t keep this up. Even if we’ve gone numb, I assure you we are dying by the day.”

Robert, as a boy, heard stories about women guerilla fighters of Jeju Island, chisel-bodied in a wooden doorway, nine or ten of them, after a run on their horses from the mainland police and transporting villagers to hideouts, but never seen or heard of since. Stories about prisoners, who urinated at length and were beaten for passing signs. Even walking at an uneven pace was a form of communication. How could they erase all meaning from themselves? Yet a meaningless world didn’t deprave them as much as a world whose true meaning was lost.

His voice arched over the pit. “One truth is that our capacity to hurt each other is equaled by our capacity to heal each other.”

The crowd responded with disbelief. They spoke of gall and rage and defeat. They waited for his final words. Robert had built his lecture toward a reveal. And he felt their hopelessness, as if they waited for a bud to signal the spring.

When a shout broke his spell, Robert saw the red light of the camera. “We have no choice but to heal our border.”

Robert pointed his toes to direct himself center stage.

For a brief moment, they must’ve sensed something was wrong. Security moved out of the pit. Microphones were pulled.

Two men with badges approached the stage. No words were spoken. They simply waited for Robert in the wings.

Robert wasn’t afraid.

Convention hall exits were barred. The podium stumbled away from him. They just saw the top of his head bowing—a black avalanche of hair.

Robert recalled his dream of a thousand faces, and his dreams unified with reality, allowing him to see their lives as beads of air that rose through the water, like a pearl necklace, like a rosary. Somewhere their faces pendulated. Somewhere they collapsed or fell silent. Somewhere their voices floated into the rafters. Somewhere blood pumped into the mud. Somewhere a spark lit a cauldron. His mother’s house on Jeju Island, the teacups at Biwon, the supermarket loading docks, the dim pool hall, the names of Busan beaches, the port outside where his mother arrived one night in 1945—the water was colder then. Now the faces dreamed of him, and it was him they recalled, and they saw Robert reach inside his suit for the whole auditorium to see.

Calmly, slowly, Robert took out the pistol. Shouts came from the back of the hall. The badges sprinted forward. Screams erupted as he aimed for his temple. Robert’s last thought was how the trigger pulled with just the slightest touch of his hand.

Insuk

That morning, the bell rang, and I opened the door and found Henry with a young pregnant woman. The woman bowed and Henry followed. It was so clear outside I saw the mountains behind them. After driving hard through the night on the Pacific Highway, they had blown their engine. Henry hadn’t said they were coming or how long they would stay, and I didn’t ask. But the van had to go to the shop, where it must wait for a new engine. Henry changed out of his shorts and slept on the recliner. Jennie fed herself at the table. She met the bottom of every bowl with her tongue. I boiled two ramen packets, and she even drank the broth. I panfried green onion pajeon—she polished off six jeons. So I refilled the banchan from my storage, dug out my ceramic pot for abalone porridge, set it out with bibimbap and kimchi jjigae, and jaengban buckwheat noodles with perilla leaves. Jennie licked the plates before I could serve a ladle of spicy yukgaejang with eggs. When Sungho came home, he couldn’t believe the dish pile. It was easy for me to take comfort in feeding her, as if my heart had taken on the shape of a spoon. It was not my son but the young woman I called to the table again, and she bounded toward me in a brilliant display of light, light, light.