Words and ‘the Thing’: Defining 68

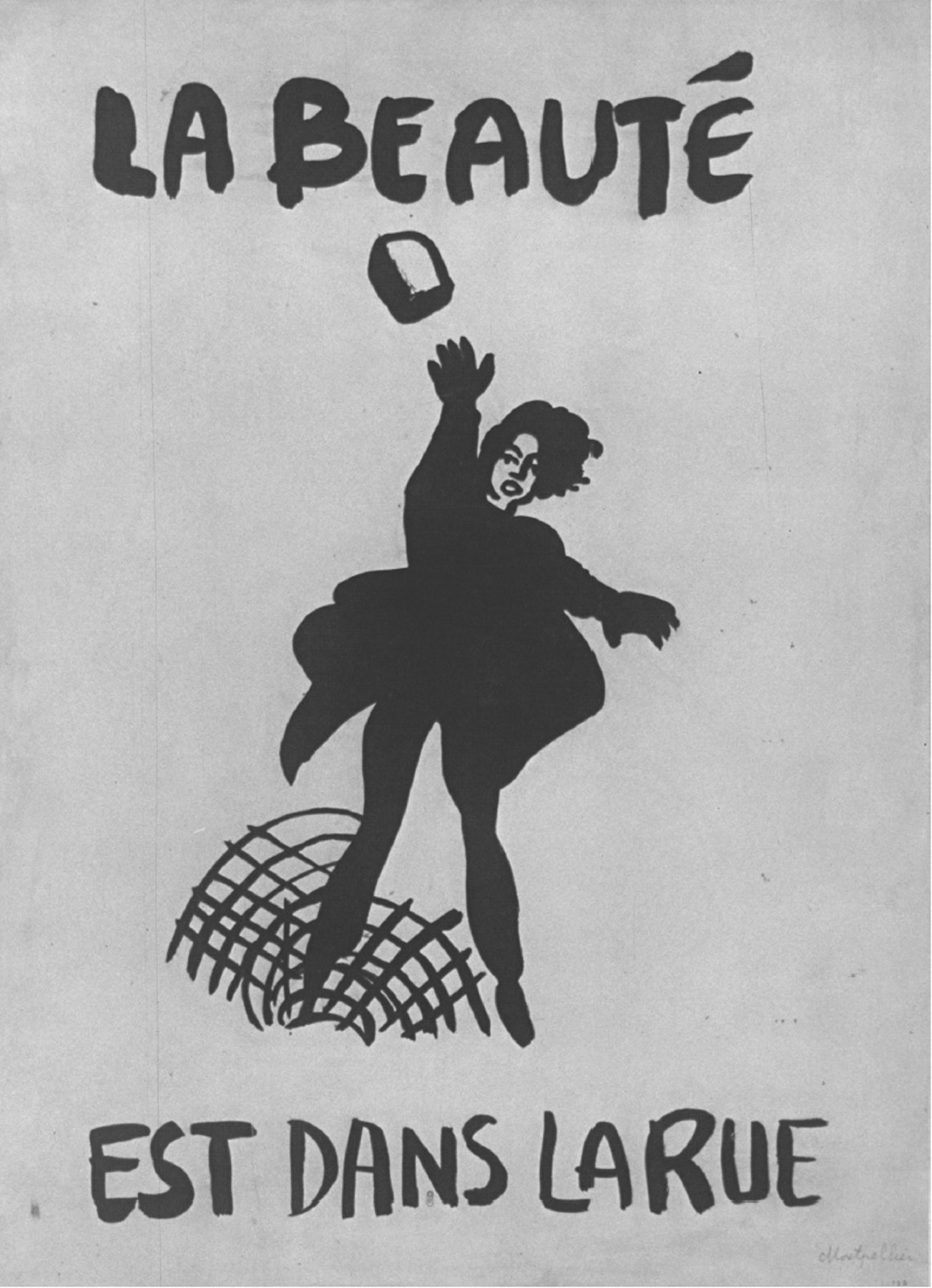

‘Beauty is in the street’. Poster from 1968.

Photo: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

The Conservative politician Enoch Powell was a central figure in the British 68. After his ‘rivers of blood’ speech in April of that year attacking non-white immigration, his presence in universities was the single most common cause of student protest. Powell’s own position, however, was strange. He was fiercely anti-American, and his stance on, say, the Vietnam War, sometimes resembled that of his bitterest enemies. Equally, he did not always agree with the numerous admirers who wrote to him. He did not share the view of one correspondent that the spread of Chinese restaurants in English villages was a front for Maoist infiltration.1 When a worried mother wrote about an article in her daughter’s copy of Honey magazine that described a girl who found sex, drugs and left-wing politics in the ‘Wild Blue Yonder’ commune, Powell gently suggested that the article might have been ironical in intent.2 Powell placed some of the letters he received in boxes marked ‘lunatics’, but put those that concerned the counter-culture, student radicalism and trade union power in a file that was labelled simply ‘The Thing’.

Many observers shared Powell’s sense that they knew broadly what a certain kind of radicalism was about while not being able to pin it down in words. There was also a curious symbiosis between 68 and its enemies: both defined themselves in terms of what they opposed, or what opposed them, more than what they proposed. Stuart Hall was the kind of man that Enoch Powell would have identified as part of ‘the Thing’. A black cultural theorist, involved in the student occupations at Birmingham University in 1968, and an exponent of what French conservatives would come to call ‘la pensée 68’, Hall wrote in 1979 that Thatcherism could be defined in opposition to ‘the radical movements and political polarizations of the 1960s, for which “1968” must stand as a convenient, though inadequate notation’.3 In April 1965, Paul Potter, a leader of Students for a Democratic Society in the United States, gave a speech after a demonstration against the Vietnam War in which he urged his listeners to identify the structures against which they were fighting and to ‘name that system’. Some assumed that ‘the system’ must be capitalism but Potter himself did not use the word. He did, however, like Powell and Hall, seem to feel that the cause for which he stood might best be defined by opposition. He said later: ‘The name we are looking for . . . not only “names the system” but gives us a name as well.’4

Words – in pamphlets, speeches, slogans and graffiti – were important to 68. A French historian wrote: ‘Revolution? May 68 was only one of words and it was first of all because the public was fed up of being governed . . . in the language of Bossuet [the seventeenth-century theologian].’5 Some in 68 assumed that getting away from formality of expression would itself be a political act. When trying to persuade Pierre Mendès France (born in 1907) to address a rally in 1968, Michel Rocard (born in 1930) offered to translate the speech into ‘patois compatible with that of May 68’.6 Articles in the alternative press in Britain and America made laborious efforts to deploy the language of the street – ‘fuzz’, ‘pigs’, ‘busted’. In continental Europe, using English (or American) expressions was sometimes a way of marking radicalism. Régis Debray, a Frenchman who regarded his fellow soixante-huitards with caustic disdain, wrote that Cahiers du Communisme, an old-style left-wing publication, was written in French but that those who wanted to read Libération, founded after 1968, ‘would need to know American’.7 The German radical left communicated in a mixture of ‘Berlin dialect, American slang and social science jargon’.8 At the same time, others discussed political theory in a language that seemed ostentatiously inaccessible. A journalist for the underground press complained that the Maoist Progressive Labour Party inhabited ‘a Tolkien Middle Earth of Marxist-Leninist Hobbits and Orcs and speaks a runic tongue only intelligible to such creatures’.9

The simplest words acquired a political charge in 68. ‘Student’ was widely bandied about, though the two most important organizations to use this name, Students for a Democratic Society in the USA and the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund in Germany, had many members who had long ceased to attend university. In Britain, the word implied modernity and was explicitly contrasted with ‘undergraduate’. Richard Crossman, a Labour minister and former Oxford don who was bitterly opposed to youthful protest, wrote in March 1968 that the trouble in the ‘old universities’ sprang from the fact that ‘everybody is a student rather than an undergraduate’.10

Words that seemed to make sense of 68 – ‘multiversity’, ‘counter-culture’ – had often been coined in the 1960s. Some on the left felt that they could name a ‘thing’ for the first time. The English feminist Sheila Rowbotham recalled, of an American friend, ‘Henry had produced a name for all these puzzling difficulties: male chauvinism.’11 Male homosexuals had used the term ‘gay’ for a long time, but in the early 1970s it acquired new political connotations. In the 1990s, a historian interviewing veterans of the British Gay Liberation Front (founded in 1971) noted how such men had grown up at a time when ‘homophile’ seemed the safest term to describe their sexuality. Her interviewees flinched when she used the word that came naturally to an activist of her generation: ‘queer’.12

Michael Schumann, of a left-wing German student association, said in 1961: ‘we belong to the movement, which originates in England under the name “New Left” and in France is called “Nouvelle Gauche”’.13 The same term was used in the United States, and in 1966 the bulletin of Students for a Democratic Society took the name ‘New Left Notes’ – revealingly, one student leader believed that the ‘new’ and ‘old’ left in America were themselves distinguished by language: ‘The old left would have said contradictions, but paradox was an intellectual discovery, not an objective conflict.’14 The sociologist C. Wright Mills, who inspired much of the student movement in the United States, had expressed his views in a ‘letter to the New Left’ – which meant in practice a letter to the English New Left Review. However, the ubiquity of the term ‘New Left’ derived in part from the very fact that it encompassed so many different things. A CIA report summed matters up thus:

Loosely dubbed the New Left, they have little in common except for their indebtedness to several prominent writers such as American sociologist C. Wright Mills, Hegelian philosopher Herbert Marcuse, and the late negro psychiatrist Frantz Fanon . . . (The term New Left, itself, has little meaning – except as a device to distinguish between today’s young radicals and the Communist-Socialist factions of the interwar period. It is taken to mean an amalgam of disparate, amorphous local groups of uncertain or changing leadership and eclectic programmes) . . . an amalgam of anarchism, utopian socialism, and overriding dedication to social involvement.15

One term not much used in 68 was ‘68’. At the time, those who hoped for revolutionary change assumed that the period in which they were living would be the prelude to something more dramatic. Some French revolutionaries did not bother to fill in their tax returns in the summer of 1968 because they assumed – until the bailiffs took their furniture away – that the bourgeois order was about to collapse. Perhaps precisely because the high drama of May 1968 was followed by a period of peace, the French did begin to talk of ‘68’ relatively early. Pierre Grappin, the dean of the university campus at Nanterre, went to the United States in late 1968 to escape from the student upheavals in his own institution. He returned to find ‘a world in which May 68 had become a directing myth’.16 Elsewhere, revolutionaries remained focused on the future for longer. In 1970 or ’71, a group of Italian militants, presumably after an evening of narcotic consumption, held a séance to call up the ghost of Frantz Fanon and ask him when the revolution would come. The date given in reply, 1984, seemed disappointingly distant.17 The words sixty-eighter or soixante-huitard implied the past tense and involvement in something that was now finished.

During 68 itself, some talked as though the mere definition of words might be an act of coercion. An American guide for those who wanted to found communes advised: ‘it would probably be a good idea to refrain from giving yourself a name . . . you will be harder to talk about without a handle’.18 When a lawyer at the trial of protesters in Frankfurt in 1968 talked of the ‘extra-parliamentary opposition’, to which they all professed to belong, the Franco-German student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit stood up to proclaim that only a ‘parliament of students’ would have the right to determine who belonged to the extra-parliamentary opposition.19

In practice, 68ers, Cohn-Bendit especially, often have been allowed to define themselves. Their accounts revolve around their own friends. Cohn-Bendit’s published We Loved the Revolution so Much;20 the American Tom Hayden’s autobiography was entitled Reunion. Relying on the memories of prominent participants in 68, though, raises problems. Confident and articulate witnesses are not always reliable. Cohn-Bendit was interviewed on French radio in late 2016. He recalled that Sartre had seemed intimidated when the two men met in 1968, which is certainly not how Sartre remembered things.21 He also believed that Roger Garaudy was the Communist leader chased from Nanterre by gauchiste students in 1968 – it was in fact Pierre Juquin.

The leading figures in 68 often had a highly developed sense of themselves as historical actors and as people who would one day be the object of historical research. The Italian guerrilla group Prima Linea dissolved itself in 1983 partly to allow its own members to provide ‘a full reconstruction of the history of the organization, its origins, development, aims and activities, to avoid leaving it to others to tell the story of Prima Linea’.22 In Chicago in February 1970, one of the last acts of members of Students for a Democratic Society who were about to go underground and form the Weathermen was to telephone a member of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, who turned up with a van to collect the movement’s archives.23 In Paris, two groups of sympathetic historians collected documents relating to the student movement in May 1968.24

The historical profession itself had an intimate relation with 68. A relation that is now itself an object of study.25 Many historians – products of the post-war baby boom and of university expansion – were on the cusp of their academic careers in 68 and sometimes felt, as Geoff Eley put it, ‘propelled into being a historian’ by their political commitments: ‘the possibilities for social history’s emergence . . . were entirely bound up with the new political contexts of 1968’.26 In France, Marc Heurgon abandoned his work on the Mediterranean in the age of Napoleon because he preferred to make history as a revolutionary member of the Parti Socialiste Unifié, rather than to write it. But others – Gareth Stedman Jones and Sheila Rowbotham in Britain or Götz Aly in Germany – saw politics and historical research as intertwined. British police archives on American radicals in London refer to Robert Brenner, later professor of history at UCLA, and Linda Gordon, later professor of history at New York University. Susan Zeiger – who sometimes published in the London underground press under the name ‘Susie Creamcheese’ – is presumably the same Susan Zeiger who now writes on women’s history.27

There was a twist, though. The historians most admired by 68ers were probably Eric Hobsbawm (born 1917), E.P. Thompson (born 1924) and, in a more complicated way, Fernand Braudel (born 1902). Braudel, a conservative who addressed the occasional fan letter to Charles de Gaulle,28 disliked the challenge to academic authority in 1968.29 Hobsbawm and Thompson were more sympathetic to the protest of their juniors but also felt distant from it. They belonged, in both political and intellectual terms, to a tradition that valued structure, rigour and a degree of intellectual detachment. Hobsbawm was mystified by the significance that radicals in Berkeley and Paris attributed to his own work on Primitive Rebels (1959). He had sought to explain ‘pre-political’ forms of rebellion but not to suggest that such rebellion should be a model for the modern world.30 Thompson wrote, half seriously, that student radicals would benefit from time in ‘a really well-disciplined organization such as the Officers’ Training Corps or the British Communist Party’.31

Perhaps the gulf between 68ers and those older historians they admired springs in part from the high value that the former placed on subjective experience – particularly their own experience – and this may also explain the gap between 68ers and those much younger historians who now make 68 an object of their own research. Three children of 68ers – Julie Pagis and Virginie Linhart, working on France, and Sofia Serenelli, working on Italy – have noted that the contemporaries of their parents were often only willing to be interviewed on their own terms, as though people who disdained property nevertheless insisted on their ‘ownership’ of their own stories. When sent a questionnaire, one subject of Pagis’s study wrote: ‘you think we can be put in files and decoded with statistics . . . I made only one choice to be myself: free and autonomous.’32

Oral histories, which have been especially influential for the study of 68, reinforce the sense that 68ers have the right to tell their own story. The subjects of oral history are often members of the same networks and have also often written autobiographies – a veteran of the American SDS drily told a historian who interviewed him in 1997 that he was ‘one of the few activists not writing his memoirs’.33 The result of this is that the same people produce multiple, mutually confirming, accounts. 68ers have a special attachment to autobiography. Some grew up in political milieux that laid a heavy emphasis on the significance that an individual might attach to their own life story, as in the Communist autocritique, or the révision de vie practised in Catholic youth movements. The widespread resort to psychoanalysis by 68ers in their later life meant, as Julie Pagis noted somewhat wearily, that many soixante-huitards had a well-rehearsed account of their life.34

Perhaps because they are dealing with an unusually assertive and articulate group of subjects, or perhaps because they feel that a magisterial Olympianism would be inappropriate to the topic, historians are curiously tentative and hesitant in their approach to 68ers. Oral histories often reproduce passages of interviews without putting them into the context that might be provided by written sources, or even by other oral histories. Sometimes simply providing banal factual detail is treated as an act of violence against subjectivity. Consider Nicolas Daum’s work on ‘anonymous soixante-huitards’, a category that turns out to mean people who were members of the same discussion group as himself in Paris between 1968 and 1972. Each interview is presented as a separate chapter but none begins with conventional biographical information or with a description of the subject of the interview. Details such as date of birth, profession and family background emerge, if at all, only in the course of interviews. When one interviewee mentions ‘our family’, Daum inserts a note to reveal that he and the interviewee are distant cousins.35

Historians themselves, though, illustrate the dangers of relying on personal memories of 68. Interviewed by younger colleagues, a chartiste (trained in the study of medieval documents) gave a vivid account of his experience of France in May 1968. Later he contacted them in some confusion. He had found his appointments diary, which seemed to suggest that he had in fact been in Italy at the time. He thought it possible that the journey to Italy had been cancelled but he was no longer sure of anything.36

By the time she published her memoirs in 1991, Annie Kriegel had come to define herself in opposition to 1968. She poured scorn on everything about the student agitation – though she thought that students at the university of Reims, where she taught in 1968, were more moderate and realistic than those at Nanterre, where she took up a chair in 1969. Berkeley, which she visited in the summer before arriving at Nanterre, was a ‘bad dream’ – the campus being marked not simply by the horrors of ‘affirmative action’ and ‘women’s studies’ but also by a plague of dogs, abandoned at the end of term, which, she claimed, began to eat each other.37 Kriegel’s account is striking but at odds with those of her academic colleagues, including her own brother.38 As for Paul Veyne and Maurice Agulhon, two contemporaries of Kriegel’s who both taught at the University of Aix-en-Provence, the former recalls 68 as a protest about style of life that had little to do with de Gaulle, whom students found ‘fusty and comic’.39 By contrast, the latter insisted that the movement had concrete and modest aims: university reform and the overthrow of de Gaulle.40

An emphasis on those who were most obviously ‘actors’ in 68 can itself be deceptive. There was a penumbra of political militancy that had an effect on many people whose relations with 68 were more complicated. The career of the film director Louis Malle illustrated a range of ways to be soixante-huitard. He played a direct role in 1968 because he was a member of the jury of the Cannes film festival that resigned in sympathy with the students that year, and he was caught up in fighting between students and the police on his return to Paris. However, as early as 1965, he had made a film, Viva Maria!, that inspired a faction of the German left – the student leader Rudi Dutschke believed that revolutionaries could be divided into those who resembled the character played by Brigitte Bardot and those who resembled the one played by Jeanne Moreau. In 1974, Malle made Lacombe Lucien, a film that was soixante-huitard its approach to the Occupation in that it subverted a certain idea of the Resistance. Malle, though still in his thirties, had already been a famous director for over ten years by 1968. His relations with politics were also complicated because he had often been fascinated by figures – such as Drieu la Rochelle – from the extreme right. Finally, in 1990, Malle made a film – Milou en Mai – which described the events of 1968 in mocking terms, as seen through the eyes of an eccentric bourgeois family in the provinces. Michel Piccoli, who played the disabused middle-aged hero of Milou en Mai, had considered abandoning his acting career in 1968 to devote himself to full-time revolutionary agitation.41

Most obviously, in Europe at least, the penumbra of 68 affected the working classes. In France, Italy, Britain, workers went on strike around 1968 and often formed alliances with other kinds of militants. Student activists were enthusiastic to embrace workers as fellow 68ers but, even during the comparatively brief periods when they were on strike, workers were rarely full-time political militants and rarely thought of themselves as being 68ers. They were also less likely than middle-class activists to write autobiographies. Indeed, there are ways in which the burst of autobiographical reflection about 68 by the middle-classes has helped to obscure working-class experience. This is illustrated by the career of the French Maoist intellectual Robert Linhart. He left the École Normale Supérieure and went to work in a Citroën factory in the autumn of 1968. He wanted to help workers make their own revolution. Writing about his experience, he was keen to avoid the self-indulgence of autobiography: ‘The bourgeoisie imagine that they have a monopoly on personal histories . . . They have a monopoly on speaking in public, that’s all.’42 However, whether he wanted it or not, Linhart’s own life – his psychological troubles, his divorce and attempted suicide – rather than that of the workers he described has been at the centre of public discussion. It has been recounted by his former friends, his daughter and his sister, Danièle, herself an academic who has worked on 1968.43

Students in 68 are portrayed in words, frequently their own words, but workers are often remembered in pictures. The strikes and factory occupations that caught the public imagination in France frequently did so because a film crew happened to be present. But audiences learned remarkably little of individuals who were caught on camera. In 1996, Hervé Le Roux (born in 1958) directed a movie called La Reprise and subtitled ‘journey to the heart of the working class’. It examined an unfinished film made in 1968 about the return to work after a strike at the Wonder battery factory at St Ouen. It featured a woman crying and saying: ‘I won’t go back, I will not set foot again in this prison, it’s too disgusting.’ The clip had been widely played in documentaries over many years and Le Roux set out to find the woman. He failed. He established that she had married, given birth to a daughter and left the factory. But he never found out her name.44

Even among the wealthy, unexpected people could in some way be touched by 68. Consider William Waldegrave. Born in 1946, he was a student leader in 68 – albeit a leader in the rarefied world of the Oxford Union. He prided himself on his resemblance to Bob Dylan and blended the personal and political in a 68ish way – recalling how he had heard of the death of Robert Kennedy while lying in bed with a girlfriend. As a visiting student at Harvard in 1969–70, he was beaten almost unconscious by the American police when he got too close to a demonstration by the Weathermen.45 He wrote to The Times denouncing the behaviour of these policemen and added that it would shock inhabitants of mainland Britain – but not, he thought, those who had endured the attentions of the B-Specials in Northern Ireland.46

Anyone reading what Waldegrave wrote during, or about, the late 1960s might assume that he was a student radical. In fact, he was an ambitious Conservative politician. As president of the Oxford Union, in the summer of 1968 he invited Quintin Hogg – a Tory with a hysterical dislike of left-wing protest – to debate the motion ‘This house is not ashamed of the British Empire.’47 In the 1970s, he was a member of a secret committee that discussed how the ‘authority of government’ might be restored. He once asked his colleagues how easy it would be in Britain to organize the kind of demonstrations in favour of order that the Gaullists had staged in Paris at the end of May 1968.48 Waldegrave was not the only Conservative who was in some respect sympathetic to 68. John Scarlett, later to become a diplomat and head of the British Joint Intelligence Committee, was an undergraduate at Oxford in 1968. He wrote to The Times – as a ‘Conservative who while not agreeing with the American position in the war has very little sympathy for the Vietcong’ – to protest against the ‘unnecessarily violent’ police response to an anti-Vietnam War demonstration that he had attended.49

Some readers will object that treating British Conservatives as 68ers implies a definition so broad as to drain all meaning from the term. They should remember that students at the epicentre of the British 68 – the London School of Economics – elected a Conservative, Peter Watherston, as president of their union in 1968 and that Watherston appears to have enjoyed better relations with the most radical students than his predecessor, a member of the Labour Party.50 More generally, the right was sometimes present in the protests of 68. In Germany, Christian Democrat students had their own version of 68, which was not one of unqualified hostility to left-wing protest.51 In Italy, some supporters of the extreme right made common cause with student protesters against the authorities.52 In France, some right-wingers (still bitter over the loss of Algeria) assumed that any enemy of de Gaulle was a friend of theirs – though some young Gaullists (those who took the general’s rhetoric on social reform seriously) also sympathized with the protests of 68. In early May 1968, a member of the Gaullist Front du Progrès pinned up a picture of Che Guevara with the caption: ‘De Gaulle is a rebel like me’.53 There were also those (such as Powell in Britain or George Wallace in the United States) who shared the rumbustious anti-establishment feelings of 68 even when they were hostile to it.

68 had so many facets and has been studied in so many different ways that work on one aspect can obscure others. Consider the recent burst of writing on the religious roots of political radicalism in the period. We learn that Tom Cornell, who was to lead anti-Vietnam War protest in the second half of the 1960s, had worked so hard to include an anti-war declaration in the statement of the Second Vatican Council that one bishop had described him as ‘an invisible Council Father’,54 that the French Dominican Paul Blanquart helped draft Fidel Castro’s closing speech at the Havana Cultural Congress of January 196855 or that the Protestant Church of Montreuil was transformed into a political centre.56 One should, however, remember that there were multiple strands in this process. Those who continued to define themselves as religious were different from those who broke with a religious upbringing. Those who redefined their religion (for example, Catholic priests who married) were different from those who embraced radical politics while staying within the rules of their orders. One thinks of the nun in David Lodge’s novel How Far Can You Go (1980), who participates in Californian anti-war demonstrations while believing that the word ‘mothers’, which protesters use to describe the police, must allude to Mother Superiors.

However, religious believers of any kind were a minority among 68ers, most of whom regarded themselves as irreligious – the role of secularized Jews in France and America was particularly important – and some of whom were positively opposed to religion. A group of progressive Catholics sought to found a new kind of community in the provençal village of Cadanet after 1968 but the other soixante-huitards who lived there seem to have regarded them with distaste.57 In any case, left-wing radicals were a minority in the Churches, some of which moved to the right in reaction against the political culture of the 1960s.58 Even the embrace of Eastern mysticism by Westerners was not always a sign of counter-cultural sympathies – Christmas Humphreys was England’s most prominent Buddhist; he was also a judge who presided over the trial of disorderly students in 1969.59

How then is 68 to be defined? It had several components: generational rebellion of the young against the old, political rebellion against militarism, capitalism and the political power of the United States and cultural rebellion that revolved around rock music and lifestyle. These rebellions sometimes interacted, but they did not always do so. 68 often subverted or circumvented existing structures. It emphasized spontaneity rather than formality. The mass meeting and the sit-in replaced formal meetings. Unofficial strikes, factory occupations and attempts to establish worker cooperatives challenged the power of trade unions as well as that of employers. Sometimes, it seemed that 68 subverted itself and that the movements of the early 1970s – women’s liberation, gay liberation and some of the organizations devoted to armed struggle – were rebellions against, as well as continuations of, aspects of 68.

WHEN WAS 68?

A musicologist has suggested that ‘68’ is, like ‘Baroque’, a term that signals a style as much as a period in time. As it happens, Baroque music flourished in the aftermath of 68, partly because the value attached to ‘authenticity’ contributed to a rise in the use of original instruments.60 Questions about how to date 68 have come to have special significance in France, where popular recollection has focused on a single year (1968) and indeed a single month (May), in which there was a concentration of dramatic events. A cartoon in Le Monde during the fortieth anniversary of the Paris events showed a confused man in a bookshop asking: ‘Vous n’avez pas quelque chose sur juin 68?’ However, and perhaps precisely because they wished to escape from the stifling constraints of a focus on one city in one month of one year, French historians have been most wide-ranging in their approach to 68 and most prone to think of that year as having long-term origins and consequences. Since the 1980s, they have used the phrase ‘68 years’ which they usually define as being the period between 1962 (the end of the Algerian War) and 1981 (the advent of the first Mitterrand government).

Curiously, the term ‘68 years’, which was originally coined with reference to France, may have the most important implications when applied elsewhere. Many places look quiet if judged against the high drama of France in the early summer of 1968 but things change if we extend the angle of chronological vision. Some see a European era of protest that began in the late 1960s and extended until at least the Portuguese revolution of 1974. Student protest in Germany peaked in 1967; more militarized political violence did not start until the following decade. Greece was under military dictatorship from 1967 to 1974 – historians talk of a ‘pre-1968’, which partly provoked the coup, or a ‘late 1968’, which helped bring the regime down.61 The Italians talk about the ‘hot autumn’ that went with strikes in 1969 and that began a new cycle of protest.

Timing matters because interpretations of 68 depend partly on where one stops the clock. One political scientist wrote briskly that ‘With the elections of 1976 the Italian 1968 ended’;62 other scholars have seen the ‘movement of 1977’ in northern Italian cities as the last incarnation of the long 68. An account of Germany that stopped in 1968 would show a student movement that had broken up, one that stopped in the autumn of 1977 would present terrorism as a major legacy of 68, one that stopped ten or twenty years later would concentrate on the origins of the Green Party and a new kind of democratic politics.

WHERE WAS 68?

There was protest across the world in 1968 – a fact that British diplomats recorded in the arch tones that they reserved for the misfortunes of other countries. In Rome, Rodric Braithwaite, a rather bohemian figure by the standards of the Foreign Office, reported that ‘with my friends from the Movimento Studentesco’ he had been to the occupied University of Rome to hear James Boggs, an American exponent of Black Power. Boggs’s southern accent was hard to follow and the audience apparently ‘did not understand how uninterested Boggs was in the white revolutionary movement’.63 Even Iceland was paralysed by a general strike the British ambassador attributed to ‘an indifferent herring harvest’.64 A delegate to a Commonwealth conference on the matter concluded that Western Australia was the only place that was unaffected.65

Many saw the long 68 as something that transcended, and perhaps subverted, national frontiers. Police chiefs and conservative politicians were obsessed by the ‘international conspiracy’ that they discerned behind disturbances in their own countries. Enoch Powell, a rare example of conservative scepticism on this topic, wrote to one of his many correspondents on the matter that he personally had always found it hard enough to launch ‘a little local conspiracy’.66 Raymond Marcellin, the French minister of the interior, wrote a book about the links that he perceived between various movements.67 The Berne Club, which coordinated the struggle of European governments against terrorism in the 1970s, had been established in 1968 to deal with ‘youthful contestation’.68

Generally, conspiracy theorists attributed such contestation to left-wing bodies, perhaps supported by Russia or China. French Gaullists – who appreciated that their own foreign policy did not fit neatly into the dichotomies of the Cold War – sometimes advanced more extravagant theories. British diplomats occasionally wondered whether the Gaullists blamed them for supporting the agitation. One reported the opinions of the general secretary of the Gaullist party:

France was the victim of an international conspiracy. He said he thought that certain foreign powers were involved ( . . . we detected a faint implication that HMG might be amongst them). When asked to be more specific, he referred to the Israelis and the Americans, both of whom, he said, had a strong interest in getting rid of General de Gaulle.69

Touring provincial France in May 1968, the ambassador reported a belief that student agitators had been trained in Berne and Amsterdam, but was relieved to find that no one spoke of London.70

Radical students relished slogans that presented themselves as part of a wider international movement: ‘Rome, Paris and Berlin, we will fight and we will win’. Some radicals came to feel like foreigners in their own country. Bob Moses, a member of the Student Non-Violent Co-Ordinating Committee, born in Harlem, who went south to help the civil rights movement, remarked that ‘When you’re in Mississippi, the rest of America doesn’t seem real, and when you’re in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.’ Later in the 1960s, especially during the Vietnam War, other activists came to express active distaste for their country. Jerry Rubin, of the Youth International Party, wrote: ‘I am an orphan of Amerika. Fuck Amerika.’71 Misspelling the country’s name was itself a political gesture. Black radicals sometimes wrote of Amerikkka. Perhaps for descendants of Jewish immigrants, such as Rubin, the word ‘Amerika’ had an additional significance – it recalled the Hamburg-Amerika line that had brought their grandparents to the country into which they were so desperate to integrate. In Britain too, rejection of ‘Englishness’ was often seen as a badge of radical respectability – though some left-wingers recognized that the most enthusiastic exponents of English values (and bitter opponents of 68) were Jewish intellectuals from Eastern Europe, such as Isaiah Berlin.

Protest was often international. In May 1968, students occupied the British Institute in Paris. The British authorities could not determine whether most of these students were British or French or drawn from further afield – the director of the institute noted bitterly that his office had acquired a large bill for phone calls made to Mexico during the occupation.72 Embassies were sites of protest and sometimes international encounters. An American marine sergeant standing guard outside the US embassy in London had a brief conversation with two British Black Power activists – he later told the Metropolitan Police: ‘I gave them some senseless crap that was more or less polite.’73

The CIA reckoned that there were 90,000 foreign students in the United States in the year 1967–8 and 80,000 Americans studying abroad at the same time. Sometimes a brief stay abroad – often recalled in highly coloured terms – formed part of young people’s image of themselves as outsiders in their own culture. Gareth Stedman Jones, later an exponent of ‘student power’, spent ten months in Paris after leaving St Paul’s School:

I went up to Oxford in October 1961, smoking Gitanes and immaculately dressed in the best that could be found on the rive gauche. My time in France reinforced my sense, shared by many of my friends in the early 1960s, of Britain as some sort of ancien régime presided over by a hereditary peer and still clinging to the decrepit trappings of Edwardian gentility.74

The number of young French people coming to Britain was higher than the number of British going to France. In July 1968, 100,000 French people, mainly teenagers, undertook language courses in Britain.75 They rarely discovered political radicalism – one assumes that bourgeois parents were happy to get their children away from the comités d’action lycéens and safely installed at an English seaside town – but travel could stimulate reflection in unexpected ways. Guy Hocquenghem, later to found the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire, recalled his séjour linguistique taken at the age of twelve in a working-class household at Shoreham-by-Sea, where ‘one dined at six’ and ate ‘haricots rouges sur toast aux petits déjeuners’.76

It was not just the young who travelled. Herbert Marcuse, the German Jewish philosopher born in 1898, had moved to America during the Second World War and was by 1968 holding court at the University of California. Angela Davis was inspired by him to go and study in Frankfurt. Marcuse himself was briefly in Paris in May 1968 around the time when the Communist leader Georges Marchais denounced his malign influence on the young. When Richard Nixon met the British cabinet in February 1969, he suggested, after Richard Crossman had made a characteristically apocalyptic intervention: ‘Why don’t we have Dick Crossman and we’ll send you Marcuse!’77

Sometimes nationalities became associated with political tendencies. When a French Communist was described as ‘Italian’, it might mean that they had been influenced by the writings of Antonio Gramsci or simply that they were more open to reform than their own authoritarian party leaders. European Maoists were described as ‘Chinese’ – though not all of them felt unqualified admiration for Mao’s China. ‘American’ or ‘Californian’ was often used as a label for those who invested their energies in new ways of living rather than the political theory that interested some of their European contemporaries. Colin Crouch wrote of his fellow students at the LSE:

It is desirable here to point out a difference in emphasis on these matters between the old-guard Marxists, who were mainly interested in the developing of their model of direct action, and the anarchists, libertarians and Americans, who were interested in building a community.78

Counter-revolution was also frequently described in terms of international comparison. The French political scientist Maurice Duverger called the law forbidding certain political parties ‘Greek’ – meaning it was the kind of legislation he associated with the Greek dictatorship of the colonels. Gaston Defferre, socialist mayor of Marseilles, said that he feared a ‘Greek’ dictatorship in his country.79

Some European left-wingers joined guerrilla movements in Latin America. Michèle Firk, born in France in 1937 and, like many French Jews of her generation, haunted by the memory of the Second World War, joined the rebels in Guatemala and killed herself after being taken prisoner in 1968.80 Régis Debray was captured in Bolivia in 1967, after having met, though not fought alongside, Che Guevara. His trial provoked a curious international alliance as Lothar Menne (German), Robin Blackburn (English), Perry Anderson (Irish aristocrat) and Tariq Ali (holder of the only Pakistani passport the Bolivian authorities had ever seen) went to try to extract him.

Debray and Guevara had both spent time in Castro’s Cuba, which became an important centre for radicals in 68. It had the advantage of being a Communist country that did not, at least at first, seem to be associated with Soviet orthodoxy. As host of the Tricontinental Conference in 1966, it seemed to stand at the centre of movements in Africa and Latin America. Algeria also illustrates some of the complexities of the relationship between radicals in the industrialized West and the Third World. Events of 1968 in France owed something to the Algerian War of 1954 to 1962 – though students were less likely to have direct memories of the war than workers, or for that matter Gaullist ministers. After Algerian independence, the Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo, in collaboration with the Algerian government, made a film, The Battle of Algiers, that was released in 1966. It was a multinational enterprise made with Algerian and French actors, but also drawing in a ragtag of people who happened to be available – including an English jazz musician busking his way around the world, who got a severe haircut and spent a few weeks as an actor playing a German legionnaire. The film was banned for many years in France but exercised a considerable influence on radicals in Britain and the US.

Large numbers of militants – the so-called pieds rouges – went to Algeria after it obtained independence in 1962. It was at an Algerian youth camp that Tiennot Grumbach first met some of the Maoists and Trotskyists with whom he would work in France in 1968. Later, Algeria became a place of refuge for some fleeing the United States – such as Eldridge Cleaver (of the Black Panthers) or Timothy Leary, the proponent of LSD, who had been sprung from a California jail by the Weathermen. By this time, however, many of the European left-wingers had become uncomfortable at the authoritarian aspects of the new state. Boumediene’s coup d’état of June 1965 encouraged many pieds rouges to leave.81

Having said all this, 68, at least in its West European and North American version, cannot necessarily be interpreted as part of ‘transnational’ or ‘global’ history. Contact between countries, and particularly between the Western industrialized democracies and the rest of the world, was often more apparent than real and, indeed, it sometimes diminished around 68. The ‘hippy trail’ – which stretched across Asia – mainly involved stoned Western teenagers talking to each other in a succession of well-established meeting points that took them from the Istanbul Pudding Shop to the beaches of Goa. The Chinese Cultural Revolution – whose image was so attractive to some Westerners – made it less likely that outsiders would actually visit the country or learn anything about it if they did.

Going to foreign countries did not always mean engaging with their populations and some travelling by left-wing activists was little more than tourism. Tariq Ali – who wrote travel articles for a smart London magazine in his spare time from fomenting revolution – was much given to phrases such as ‘Prague is a city for all seasons’. In fact, Prague illustrates the limits of transnational exchange in 68. It is true that the Prague Spring coincided with the peak of many protest movements in the West and it is true too that Western students usually sympathized with their contemporaries in Prague. However, surface similarities between Czechoslovakia and the West could be deceptive. Tom Hayden had a brief fling with a Czech woman during a stopover on his way to North Vietnam. The atmosphere reminded him of Berkeley but the politics were different – he discovered that his lover, like many intelligent Czechs, simply assumed that every word emanating from the regime was the exact opposite of the truth and, therefore, that American intervention in Vietnam must be a good thing.82

The Czech Jan Kavan was one of the student leaders who participated – along with Tariq Ali, Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Karl Dietrich Wolff – in a BBC television programme about student revolt in June 1968. But he was able to address a Western audience, and to escape relatively easily when the tanks rolled in, because he had been born in London and had an English mother. As for the most famous of all Czech 68ers, one of Vaclav Havel’s biographers describes how he was in Paris, on his way to New York, on 13 May 1968. He had arranged to meet the émigré Pavel Tigrid at Paris airport. Havel had no visa to enter France but suddenly airport staff and customs officials walked off the job to join the general strike – leaving him free to enter their country:

the barriers between East and West collapsed . . . Borders were meaningless. Identity papers were obsolete. Surveillance was just a word. Nobody asked questions. The distinction between citizen and alien, between insider and outsider, was struck down. Everybody was equal.83

It is a wonderful story, but it is not true. Havel had already been in New York for three weeks on 13 May.84

The rhetoric of global connection could cover activities that were parochial. Richard Neville arrived in London to join his sister Jill after having hitch-hiked overland from Australia. However, Neville’s grasp of politics outside west London was sometimes uncertain. He recalled an anti-Vietnam War demonstration of 1969 where he and his girlfriend ‘were so baffled by the proliferation of New Left splinter groups [we] joined the ranks of Aussie expats distinguishable by a high-held national flag’. Neville, still sentimental about his native country, was upset when Germaine Greer grabbed the flag and set it alight.85

For some, national culture remained important in 68. First there were some radicals who actively embraced national culture. This was true in France, where a specifically French revolutionary tradition was referred to with almost obsessive intensity, and also true, at least in the early part of the 1960s, for some on the American left who were keen to claim connection with native forms of radicalism as an alternative to international Marxism. Even gestures that seemed like rebellions against the nation might take distinctively national forms. The French demonstrators who chanted ‘Nous sommes tous des juifs allemands’ were referring to France’s experience of occupation, and their hostility to currents that they associated with collaboration was matched by their enthusiasm for those they associated with resistance. To an even greater extent, German radicals had specifically German reasons for rejecting part of their national past.

Sometimes the militants of 68 were preoccupied with communities that were smaller than the state instead of, or as well as, ones that were larger than it. Regionalism was important in western France, especially Brittany. Northern Ireland saw a rising by Catholics who wanted to break with the United Kingdom, as well as by Protestants who wanted to defend their special status within that kingdom. Members of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) rebelled against Anglophone rule in Canada though not all of the members were Francophone, or even Canadian. Until the movement’s leaders finally fled to exile in Cuba, the FLQ provided inspiration, and occasionally practical help, to radicals in the United States and France – though one assumes that their notion of anti-imperialism was different from that of Charles de Gaulle, who saluted ‘Free Quebec’ in 1967 and began 1968 with a mischievous expression of goodwill to the French population of Canada. In Belgium, the University of Louvain was riven by conflict that sprang partly from those who wanted to defend the rights of Flemish speakers.

Even ideas that apparently held international appeal could change their sense as they moved across frontiers. The ‘personalism’ of the Catholic philosopher Emmanuel Mounier probably seemed more radical to young Americans than it had done in France, where the Catholic Church was associated with the political right. Likewise, membership of the Communist Party meant something different to Europeans, particularly those old enough to remember Stalinism, than it did in the United States. Edgar Morin, the French author of Autocritique (1959), the classic text by a disillusioned ex-Communist, admired the black American activist Angela Davis, but her decision to join the Communist Party gave him ‘a familiar and painful sense of hypocrisy’.86

There was a revealing difference in the reception of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus on either side of the Atlantic. Sartre, whose importance had seemed to diminish in the 1960s as structuralism displaced existentialism in intellectual fashion, shot to new heights of fame during the student protests of 1968. His call for political engagement suited the mood of the times – and he had the advantage of being physically present in the Latin Quarter. Camus, on the other hand, had been killed in a car crash in 1960. His ideas played little role in the French 68. His reputation on the French left had been damaged by his reluctance to condemn France during the Algerian War and by the venomous assault on his philosophical ideas published by Sartre’s protégé Francis Jeanson in the journal Les Temps Modernes.

In the United States though the relative prestige of the two authors was reversed. Sartre was unattractive to those who had not been brought up on a diet of continental philosophy. Camus had qualities that particularly appealed to Anglo-Saxon youth. He was, in conspicuous contrast to Sartre, physically attractive, and his early death had frozen him, like James Dean and John F. Kennedy, into a perpetual youth. His writing was clearer and more obviously moral than Sartre’s. John Gerassi, the son of a friend of Sartre’s who had moved to the US, began postgraduate research on the Sartre/Camus split at the University of Columbia but abandoned the exercise. He later explained to Sartre: ‘I could never get a doctorate in the United States by criticizing Camus.’87 Young Americans were particularly prone to read Camus’s variety of existentialism as having religious connotations – L’Étranger was published in England as The Outsider but published in America with a title that sounded faintly biblical: The Stranger. The sales of this novel peaked in the US in 1968 at 300,000 copies.88

Sartre did attract a revived interest in the United States around 68 but this was mainly because Black Power activists read his preface to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth – a book that was itself the product of complicated transnational exchanges since Fanon, born in Martinique and educated in France, had written it while teaching Algerian militants in Tunisia. His thinking about race had been inspired in part by reading Chester Himes – a black American living in Paris who wrote hard-boiled detective stories set in New York.

As was stressed in the Introduction, this is a book about the Western industrialized democracies and it examines the long 68, which stretches from the early 1960s to some point in the 70s. However, it is a work with ragged edges. No account of 68 can ignore the late 1990s, when some former 68ers – Joschka Fischer, Bill Clinton, Jack Straw – held high office. In geographical terms, Western Europe and America cannot be entirely separated from the rest of the world. Even China occasionally impinged on the Western 68. Western Maoists may have had only the most abstract conception of what the Cultural Revolution really meant but British officials had to deal with its effects in Hong Kong and the New Territories.89

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I do not believe that the study of 68 can be separated from what might be called ‘mainstream political history’. Some 68ers dismissed all conventional politics and they often reduced these to cursory abstractions – ‘fascism’, ‘imperialism’, ‘power’. Colin Crouch wrote that the attitude of his fellow students to authority, and particularly their propensity to assume that occupying a British university might be legitimate as a means of expressing discontent with American foreign policy, could be explained by the fact that ‘[for] the far left there is no such thing as individual “authorities”. There is just one continuous, monolithic “authority”.’90

But the divisions were never as sharply defined as some on both sides liked to pretend. The radicalism of the late 1960s often emerged out of reformism earlier in the decade and it sometimes blended back into more conventional kinds of politics – or labour organization – later in the 1970s. Far from interpreting this as a sign that 68ers sold out or that they were manipulated by the system, it seems to me that the long-term importance of 68 lies precisely in the ways that it interacted with mainstream politics.