On 1 May 1960 an American U-2 spy plane was shot down in Russian airspace. To save face, the Eisenhower administration encouraged NASA to release a press statement saying that the plane was a weather-research plane, and that it had accidentally flown into Russian airspace after the pilot had lost consciousness. One can only imagine how much Khrushchev must have relished his next move. He produced both the CIA pilot, Francis Gary Powers, who had been captured unharmed, and the plane’s intact spying equipment. Eisenhower had been advised that the plane would have blown up mid-air and that pilot was almost certainly dead; now he was caught out in a lie, just months before an election. Tensions between America and the USSR escalated. The lie also fed into what was becoming a growing rift between press and government in America, a rift that would only widen during the 1960s.

On 8 November 1960 John F. Kennedy beat Richard Nixon to the Presidency. America’s oldest-ever President was succeeded by its youngest. During his campaign Kennedy had taunted Nixon about Eisenhower’s caution on defence, and his lack of investment in space. In his farewell address to the nation Eisenhower ‘highlighted the danger of allowing the political and economic interests of military contractors and bureaucrats to hijack the national security agenda for their own gain’. Kennedy had played to public fear, encapsulated in the notion of a missile gap, a term he had begun to use frequently from 1958 onwards. The truth, however, was somewhat different. Russia was still some way away from having an operational ICBM when Kennedy took office, whereas America now had 160 operational Atlas ICBMs and nearly 100 Thor and Jupiter IRBMs. The UK had taken the bulk of the Thors, from where they could reach Russian soil. Bizarrely, the agreement was that the weapons, once on British soil, would become British property and were to be deployed by the RAF, but the nuclear warhead each carried would continue to be American property and come under American control. No one wanted von Braun’s Jupiter missiles, except with great reluctance Italy and Turkey, which took some in 1959.

Korolev’s ‘workhorse’ R-7 rocket was a crucial and reliable booster rocket for the Soviets but there were practical considerations – even with a fully functioning heat shield – that ruled it out as an ICBM. The rocket was so large it could only be launched from one location, and so was easily identifiable by an American spy plane. It took so long to fuel that American bombers would have been on the scene well before the R-7 ever got off the launch pad. Once Khrushchev began to realize the R-7’s limitations as a missile he looked to other rocket designers. In the end only seven R-7s were ever deployed and none for military purposes. The R-16 ICBM was the missile on which Khrushchev was pinning his hopes, the work of the rocket designer Mikhail Yangel.

The Soviets had attempted to test-launch an R-16 ICBM in October, the month before Kennedy won the Presidential election. The massive rocket blew up on the stand and vaporized the Chief Marshal of Artillery, Mitrofan Nedelin, and 71 officers and engineers (some accounts give a much higher number). Yangel, who was several hundred yards away smoking a cigarette, survived. Later, Khrushchev brusquely asked him why he was still alive. Yangel suffered a heart attack shortly afterwards. An Italian news agency reported the disaster a couple of months after the event but the source was unconfirmed. The accident remained a rumour in the West until it was confirmed by Russia in 1989.

NASA’s first Director, T. Keith Glennan, left his post in January 1961, coincident with President Kennedy assuming office. In just a few years Glennan had turned NASA into an enormous umbrella operation that had subsumed the Naval Research Laboratory and Medaris and von Braun’s Huntsville operation, the 8,000 employees of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, the Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, ARPA and several satellite and lunar programmes, including Mercury. Even so, NASA was still fairly modest in size compared to the behemoth it would become.

The new President seemed, for the moment at least, no more interested in space than Eisenhower had been. Kennedy’s science adviser, Jerome Wiesner, was even less sympathetic. At least 17 people turned down the job of NASA director when approached by the White House before James Webb accepted.

On 14 April, two days after Gagarin’s orbital flight in Vostok I, Webb met with the President and Lyndon B. Johnson. Kennedy still wasn’t ready to commit to a space race. Less than a week later, he sent a memo to Johnson asking what America could do decisively in space to beat the Russians. The reason for the change of heart and mind was political. In the middle of that week a brigade of over two thousand Cuban exiles had attempted to invade their homeland, landing at the Bay of Pigs. The operation had been originated by Eisenhower and the CIA, supposedly in secret, in an attempt to wrest Cuba from its increasingly Communist-leaning government, and had been approved by Kennedy in the first month of his administration. America’s aggressive involvement had, however, become obvious. Kennedy rejected calls for direct air strikes against Cuba and disastrously failed to provide the air cover the invading forces needed and which had been promised. Over a thousand exiles were arrested, hundreds were injured, and over a hundred killed. The Cuban army suffered a greater number of casualties but the American invasion was quashed. Kennedy’s reputation suffered a severe blow just a few months into his Presidency. It was America’s first defeat in the Third World. Relations between Cuba and the Soviet Union became much stronger. Emboldened by his success, and angered both by the presence of von Braun’s Jupiters in Italy and Turkey, and by the U-2 spy plane incident, Khrushchev made the decision to base R-12 and R-14 IRBM missiles in Cuba.

Johnson already knew what his answer was to be to Kennedy’s question, but decided anyway to ask von Braun what he thought America could do in space to trump the Russians. If Johnson wanted something from NASA, he sometimes circumvented Webb and phoned von Braun directly. Even if Johnson had already made up his own mind, the fact that he was asking von Braun a question he hadn’t asked of Webb or of the generals is significant. Von Braun said that America did not stand a chance of beating the Soviets to a manned laboratory in space. There was a ‘sporting chance’ of beating them to the soft landing of a probe on the moon and of sending a three-man crew in orbit around the moon, though the Soviets might beat the US by sending a single man with minimal consideration of his safety. ‘We have an excellent chance,’ von Braun wrote, ‘of beating the Soviets to the first landing of a crew on the moon (including return capability, of course).’ He predicted that the US could, ‘going hell for leather’, achieve this objective by 1967 or 1968. Johnson had already replied to Kennedy by the time he received von Braun’s letter, but their thinking exactly coincided, and some of von Braun’s language resonates with the language Kennedy would use when he made his plan known to the American people. A manned moon landing it was to be. Johnson was fired up and so was von Braun. Webb, however, took some persuading, and only agreed so long as there was a long-term commitment to space exploration generally. Early drafts of the President’s speech set the target date as 1967, but Webb asked for the vaguer date of the end of the decade.

To lift three men out of the Earth’s gravitational pull would require rocket power 10 times larger than any that existed at that time. If it could be pulled off, the achievement would be the result of a show of literal power, which played, of course, into von Braun’s hands as pre-eminent builder of powerful rockets.

On 25 May 1961 Kennedy proposed, in a ‘Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs’, that America shoot for the moon. His science adviser, Wiesner, who remained opposed to the idea, asked Kennedy never to refer to Project Apollo as a scientific enterprise. And he never did.

These are extraordinary times. And we face an extraordinary challenge. Our strength as well as our convictions have imposed upon this nation the role of leader in freedom’s cause . . . I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish . . . Now it is time to take longer strides – time for a great new American enterprise – time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

‘Everyone knows where the moon is,’ von Braun said of Kennedy’s clear objective, ‘what this decade is, what it means to get some people there – and everyone knows a live astronaut from one who isn’t.’ Some scientists thought that Kennedy’s plan was over-ambitious and would take at least 30 years. Eisenhower told reporters that it was ‘a mad effort to win a stunt race’. He said it was ‘just nuts!’ In response von Braun said that Lindbergh’s trip across the Atlantic had been a stunt too, but look what happened afterwards, the whole aviation industry took off. He said that Apollo would be the ‘wisest investment America has ever made’. It wasn’t about getting to the moon any more than for Lindbergh it had been about getting to Paris, it was about being first – ‘No one remembers the second man to fly the Atlantic ocean’ – and the technological spin-offs that would follow such a race. Eisenhower told the press that it was a waste of $40 billion. NASA calculated that Project Apollo would cost $10 billion. Webb argued that there were bound to be overruns and suggested $13 billion. When he went to Capitol Hill, on the spur of the moment, he came out with a figure of $20 billion, perhaps on the basis that everything always ends up costing twice as much, whether it’s installing a new kitchen or flying to the moon. It would eventually cost around $25 billion.

Kennedy expected the proposal to be voted down, but it was carried after a debate that lasted for just one hour with only five senators choosing to speak. NASA’s annual budget was raised from $1 billion to $5 billion. If von Braun had got his satellite into orbit first, as he might well have done if he had been given free rein, the space race would surely have taken a different course. It seems highly unlikely that the American public of the time would have so readily funded such a costly enterprise without the motivating force of fear.

In the 1960s, the pace of the space race gathered even greater momentum.

21 July 1961. Second Mercury flight. Capsule: Liberty Bell 7. The booster was a Redstone rocket. Pilot: Gus Grissom. Suborbital flight lasting 15 minutes and 37 seconds.

6 August 1961. Second Vostok flight. Pilot: Gherman Titov, at 26 years old even today the youngest astronaut to go into space. (When I don’t distinguish between astronauts and cosmonauts in the usual way, I use the word astronaut to mean spacemen of any nationality.) Flight time: 1 day, 1 hour, 18 minutes; 17½ orbits. After he parachuted out of his craft on re-entry, he almost landed on a train track. A gust of wind blew him into a field at the last moment.

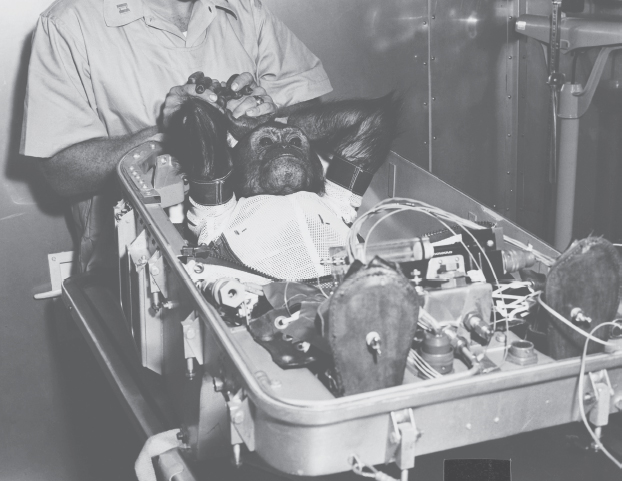

29 November 1961. In a dry run for the upcoming first manned orbital flight of an American, Enos, a chimpanzee, was sent into orbit on an Atlas rocket. Like Ham, he was controlled by being given electric shocks. He made two orbits of the Earth before the mission was aborted due to technical problems. After he was picked up Enos ran around the deck of the rescue ship ecstatic, shaking the hands of his rescuers, and masturbating. He died of dysentery, unrelated to his experience of being in space, on 2 November 1962.

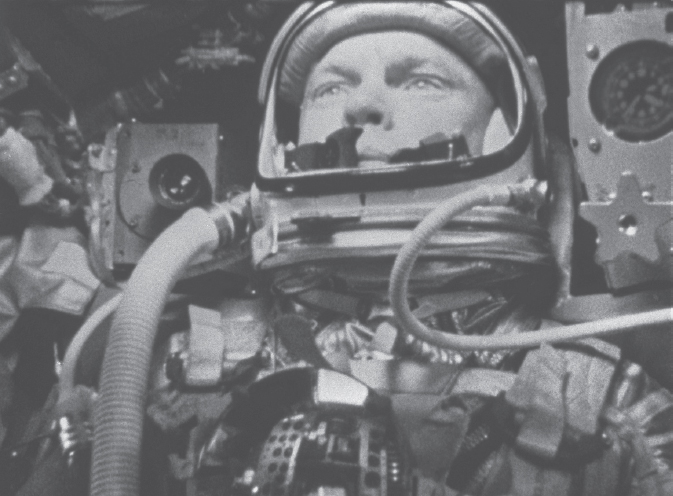

20 February 1962. Third Mercury flight. Capsule: Friendship 7. The booster for this and all subsequent Mercury flights was an Atlas. Pilot: John Glenn. Flight time: 4 hours, 55 minutes, 23 seconds; 3 orbits. John Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth.

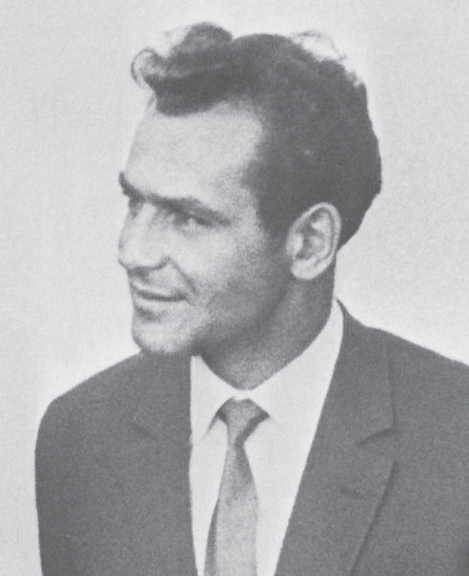

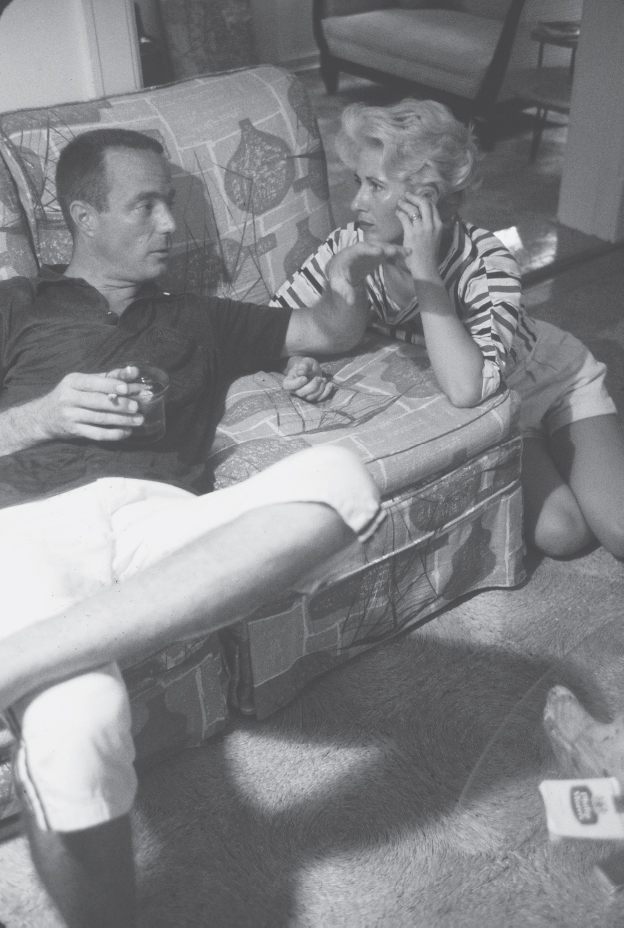

24 May 1962. Fourth Mercury flight. Capsule: Aurora 7. Pilot: Scott Carpenter (pictured left with his wife, Rene). Flight time: 4 hours, 56 minutes, 5 seconds; 3 orbits.

11 August 1962. Third Vostok flight. Pilot: Andriyan Nikolayev. Flight time: 3 days, 22 hours, 28 minutes; 64 orbits.

12 August 1962. Fourth Vostok flight. Pilot: Pavel Popovich. Flight time: 2 days, 22 hours, 56 minutes; 48 orbits. The first time that two spacecraft were in orbit at the same time. The two cosmonauts came within a mile of each other in space.

3 October 1962. Fifth Mercury flight. Capsule: Sigma 7. Pilot: Wally Schirra. Flight time: 9 hours, 13 minutes, 15 seconds; 6 orbits.

15 May 1963. Sixth and last Mercury flight. Capsule: Faith 7. Pilot: Gordo Cooper. Flight time: 1 day, 10 hours, 19 minutes; 22 orbits.

14 June 1963. Fifth Vostok flight. Pilot: Valery Bykovsky. Flight time: 4 days, 23 hours, 7 minutes; 82 orbits.

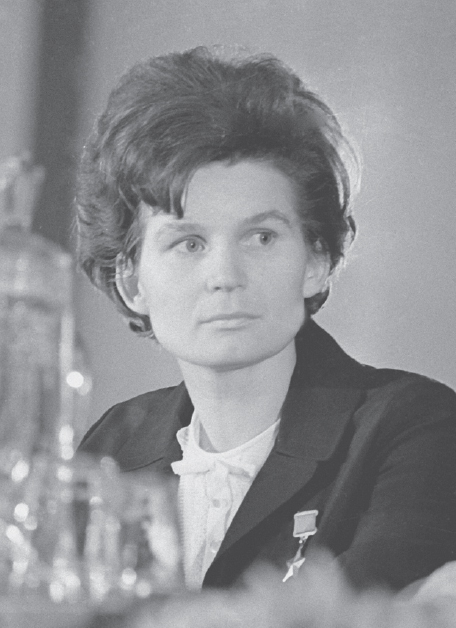

16 June 1963. Sixth and last Vostok flight. Pilot: Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Flight time: 2 days, 22 hours, 50 minutes; 48 orbits.

It would be a long time before America got a woman into space, although 13 women made it through NASA’s training programme. Jerrie Cobb, who had set records for speed, distance and altitude, petitioned Congress, but Lyndon Johnson said, ‘Let’s stop this, now.’ John Glenn testified before a House Space Committee in 1962 against sending women into space. His main argument seemed to be that no man would want to see a woman urinate, or worse, in a confined space. Glenn took along his wife, Annie, who was in agreement with her husband’s recommendation. Such a ruling is of course unenlightened from our perspective, but other decisions NASA made seem surprisingly liberal, particularly for the time. Some women were employed by NASA as so-called computers. In 1952 Katherine Johnson heard that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (before it became part of NASA) was looking not just for women mathematicians but black women mathematicians. She got a job working in their guidance and navigation department. Years later she calculated the trajectory and launch window of the first Mercury flight. Shortly after, though NASA began to use electronic computers Glenn insisted that she personally check the computer calculations for his upcoming flight.

In 1961, the first contract awarded after Kennedy’s announcement of the moon goal went to the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. A team headed by Margaret Hamilton, then aged 25, went on to create Apollo’s on-board flight software.

In 2015 Katherine Johnson was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. The same award was given to Margaret Hamilton in 2016.

Each Mercury Seven pilot was paid a salary by NASA of $7,000 a year plus life insurance. No one else would insure them. The modest salary was boosted by a share of a $500,000 deal with Life magazine. Three full-time Life reporters were assigned to the project. One of them was Loudon Wainwright II, the father of the singer Loudon Wainwright III, and grandfather of Martha and Rufus Wainwright. NASA tried to direct what the astronauts’ wives should wear for the first photo-shoot. Pink lipstick, they insisted. Life manipulated the photograph and changed the colour to red.

NASA wanted their astronauts squeaky-clean. They were told how to behave at social and media events: long drink, make it last; knee-length socks, no visible calves; answer the question, not too long, not too short. As one of them wryly observed, the world may have been sloppy but at NASA everything was very precise. If only they could all be like John Glenn: Bible-reader, Sunday-school teacher. Glenn had been disappointed not to be the first American astronaut into space; he was even more disappointed that Shepard was chosen. He was furious when it came out that Shepard had been having an affair with a young Mexican woman. Glenn had become the unspoken father of the Seven. He called a closed meeting and lectured them on how they had a moral duty not to philander. Shepard’s affair was hushed up. There would be more meetings in the future. The astronauts called them ‘séances’.

Shepard may have been the first American in space but Glenn, as first American to orbit the Earth, got the greater attention. He came back to the largest tickertape parade since Lindbergh’s. He insisted that all seven of them should parade together, along with their wives.

NASA didn’t always get its own way, not even with John Glenn. Vice President Lyndon Johnson wanted to be seen congratulating Glenn’s wife and was trying to get into their home along with three major network news crews. Loudon Wainwright was with her at the time, and Johnson sent in word that he was to leave. Annie Glenn wasn’t having it and wouldn’t let them in. Webb told Glenn he needed him to get his wife to cooperate. Glenn told his wife she should do whatever she thought was best. She told Wainwright to stay where he was. Johnson was furious and later let it be known that he would be happy to see the Life contract cancelled. It wasn’t, but Glenn had to get to the President himself to save the deal.

Other perks followed as the astronauts quickly became household names: low-rate mortgages, new-ish Chevrolets offered at a huge discount. For whatever reason – perhaps it played better with the public – the car had to be seen to be a used car. By today’s standard’s these perks might seem modest, but in some quarters there was dissent. NASA may have been a civilian operation but the Mercury Seven astronauts were all from the military, and some of their colleagues were fighting or would soon be fighting in Vietnam.

There were seven of them but only six flights. Deke Slayton was meant to be the second American to orbit the Earth, but he was grounded when it was discovered he had an irregular heart rhythm. He was, instead, given what would turn out to be a powerful position, the first Chief of the Astronaut Office. It was he who got to decide which astronauts went on which flights. He would not make his own first flight into space until 1975. After Mercury came to an end, the Seven wrote a collective memoir published as We Seven, the title seemingly in homage to Lindbergh’s first autobiography, We.

Almost anything anyone did in space during this time was a first of some kind. Gagarin was the first man in space, the first to orbit the Earth, the first to see the curvature of the Earth, the first to experience a substantial period of weightlessness. Previously he had only experienced weightlessness for a second or two in a specially adapted freefalling elevator.

Gagarin had been weightless for less than two hours; Titov was weightless for more than a day. The experience made him unwell for much of his flight. Titov has the dubious honour of being the first human being to vomit in space, a detail the West would only learn much later. None of the Mercury Seven astronauts suffered from space sickness, but roughly half of the future Apollo astronauts would. Something about how snugly the Mercury astronauts fitted inside their capsules seems to have made a difference. Vostok capsules were between two to three times the size of Mercury, still not exactly roomy, but that extra degree of freedom of movement seems to have been what instilled nausea and vertigo in Titov and other cosmonauts. Titov eventually managed to go to sleep during his flight, but after he returned to Earth continued to suffer balance problems for a few days. Such tests of endurance were vital if there were ever to be manned expeditions to the moon, and beyond.

Shepard had to make do with being the first American in space, Glenn with being the first American to orbit the Earth. Nikolayev, the third Russian in space, and the seventh man in space, was the first astronaut to unstrap himself and experience weightlessness unfettered by straps. And so on. The recording of firsts was one way the momentousness of what was being achieved could be acknowledged, but soon even firsts lost their ability to instill wonder or awe.

Another way was through the astronauts’ own words; their descriptions of what they had experienced. Gagarin said that weightlessness had made him feel euphoric. Something about the experience was almost childlike. Glenn said it was amazing how quickly he had got used to it: ‘You feel completely free. The state is so pleasant . . . that we joked that a person could probably become addicted to it without any trouble. I know that I could.’ Gagarin had attempted to describe the extraordinary colours he had seen at the horizon. ‘Such a pretty halo,’ he said. ‘The horizon became bright orange, gradually passing through all the colors of the rainbow: from light blue to dark blue, to violet and then to black. What an indescribable gamut of colors! Just like the paintings of the artist Nicholas Roerich.’ Roerich was a mystic and follower of cosmism. His paintings were often described as being hypnotic, reflecting the artist’s own interest in hypnosis. He is most famous these days for having designed the costumes and sets of the first production of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Gagarin’s appeal to art is telling. It wouldn’t be long before other astronauts also appealed to poetry.

Glenn’s description of sunset in space was almost identical to Gagarin’s: ‘What can you say,’ he said, ‘about a day in which you get to see four sunsets?’ As the sun descended, the light in the sky reduced to a band at the horizon, at first ‘almost white in color. Then, as the sun sank deeper over the horizon, the bottom layer of light turned to bright orange, with layers piled on top of it of red, then purple, light blue, darker blue, and finally the darkness of space. It was a fabulous display.’ After his flight, Carpenter said he took comfort from the fact that out there every sunset, spectacular as it was, looked exactly the same.

From the start there was a desire among the first astronauts to bring back photographic evidence of what they had seen (another attempt to share with the public what they had experienced out there). Titov was the first to take a camera into space. Glenn took a camera, too, but he had had to insist. In the end he bought his own: $19.95 from a local drugstore, and took it on board as personal equipment. NASA hadn’t approved, not wanting him to get distracted during what was going to be a relatively short flight. Walter C. Williams, in overall charge of the launches, thought that cameras were a hazard, took up space and added unnecessary weight. It set the tone for what would be NASA’s ongoing antagonism to what they sneeringly called ‘tourist’ photographs. One of the first designers of the Mercury capsule had even wondered if it might not be easier to build one without any windows at all, or perhaps with a periscope. Certainly taking photographs of the Earth had not been a high priority for Mercury. During Shepard’s first Mercury flight, he and the instrument panels were recorded almost continuously, but little effort had been put into recording the flight as seen from the Shepard’s perspective. A single camera with a wide-angle lens was suspended on a periscope and took whatever photographs it could of the world outside. The photographs were of poor quality and, because of the shape of the lens, distorted. They provided no corroborating evidence of the ‘beautiful Earth’ Shepard said he had witnessed. Glenn had found it hard to take photographs wearing thick gloves. Though he had managed to take 70, not surprisingly none of them was of great quality. In any case how could he possibly capture on film colours that he described as being more brilliant than any seen in a rainbow?

During the fourth Mercury flight Scott Carpenter became so overwhelmed by the view that he manoeuvred the craft so he could get a better view of the Earth, and ignored repeated warnings from the ground that he was using up a lot of fuel. When he landed, he was over 200 miles short of where he should have been, and couldn’t at first be found. ‘I’m afraid we may have lost an astronaut,’ said anchorman Walter Cronkite. After a few hours a helicopter found him in his life raft, hands behind his head chewing space food. A photo of Carpenter in the raft appeared in the press the following day. Mercury flight director Chris Kraft, who was known for his ‘forthright views on almost everything’, was heard to say: ‘That sonofabitch will never fly for me again.’

NASA was generally suspicious of intellectuals, and even more suspicious of a gathering world force: the 1960s. Carpenter and his wife represented both. They liked literature and philosophy, and skiing. In an interview with Life, Carpenter talked of his ‘inner weather’, words taken from Robert Frost. He worked out on a trampoline, which he described as being like a kind of earth-bound flying. It was all a bit beatnik for NASA.

Beatnik: After Sputnik there was a short-lived craze for neologisms ending in -nik. Beatnik is the only survivor. It was coined in 1958 by Herb Caen, a journalist working out of San Francisco; the beat in beatnik is as in Beat generation, a term invented by Jack Kerouac just a few years earlier.

Astronauts weren’t supposed to be part of the counter-culture. They weren’t supposed to get overwhelmed by the view. It wasn’t very right stuff. The right stuff was not to care about such things. Scott Carpenter never did go into space again.

Despite their reservations about ‘tourist’ photography NASA had set up a small advisory group responsible for photography led by Richard Underwood.

As a young man serving in the navy, Underwood had volunteered to observe the first Bikini Atoll atomic test of 1946. Cameras were banned but Underwood built, and surreptitiously used, a pinhole camera, using photographic film his mother smuggled to him inside a bar of chocolate. He was paid danger money of seven months’ double pay, which he used to finance a university degree. He said he learned aerial photography from a light aircraft, hanging out the door with a rope holding him in place. He served in the Pacific in the Second World War; and then, after he had graduated, joined the US Army Corps of Engineers as part of an army project to study the Earth’s geological features as seen from the air. After 4,000 hours in B-17s he became deaf in one ear but could identify any region of the Earth from an aerial photograph. ‘Every little piece of ground has a signal that it gives off,’ he said.

When he married a woman from Honduras, he lost his army security clearance and needed to look for new work. One day the phone rang. A man with a heavy German accent was on the other end of the line. It was Wernher von Braun:

‘They tell me you know something about cameras that fly high,’ he said.

‘Well, up to 70,000 feet,’ Underwood replied.

‘Do you think one could work at half a million feet?’

‘That would be in space.’

‘Well, let’s give it a try. Come to Alabama. I want to talk to you.’

Underwood didn’t need the same security clearance to work for von Braun, and so for a couple of years in the late 1950s he was in Huntsville finding out how to attach cameras to some of the first Redstone rockets fired from Cape Canaveral. The images that came back were almost entirely of the ocean, but the experience got him thinking about photos of the whole Earth. From there Underwood found his way, via the Space Task Force, to Project Mercury, where, at first, because of the objections from senior NASA personnel, he was able to do very little.

In the run-up to the penultimate Mercury flight, Wally Schirra had at first been sceptical about the value of photographs of the Earth seen from space but then made a complete volte face – presumably Underwood’s doing – and insisted on taking his own Hasselblad, not a cheap store-bought camera like the one Glenn had taken. He was told that he couldn’t for a list of baroque reasons: the leather might emit a gas; without the leather casing, sunlight striking the stainless steel camera might blind him; if the glass broke it would float around the craft in zero gravity, and so on. Schirra was close to tears, reacted so badly that NASA management had a change of heart. He could take the camera so long as modifications were made. Victor Hasselblad himself agreed to make them. The camera was very precise and reliable but Underwood had been allowed to spend just three hours training Schirra in the art of space photography. He came back from the fifth Mercury flight with photographs that were either over-exposed or images of cloud cover.

Schirra, too, had been taken by the sunsets, but, presumably with Carpenter’s fate in mind, he said later that he was aware that if he had got lost in wonder he might have wasted a flight and maybe his life.

Gordo Cooper was the youngest and most inexperienced of the pilots but the most experienced photographer of the Seven. He had exceptional eyesight. During the last Mercury flight, he said he could see, from 101 miles up over Tibet, the smoke rising from the chimneys of individual buildings. His reports were at first dismissed. Experts said he must have been hallucinating. We now know that the human eye can isolate linear features in a way a camera cannot, human sight being, of course, nothing like the way a camera sees. We also know that vision is less distorted in space than it is in the Earth’s atmosphere. Afterwards his descriptions were independently verified.

Photographic emulsion couldn’t capture what the first astronauts saw, nor mere words; perhaps then it is no surprise that, right from the start, God inserted Himself into the space race. Yuri Gagarin said that he had ‘looked and looked and looked’ but hadn’t seen God. Except that Gagarin – a member of the Russian Orthodox Church, who baptized his daughter into the faith soon after his orbital flight – hadn’t said anything of the sort. The words, or words like them, were Titov’s. ‘Some say God is living there [in space],’ Titov had said after the Soviet Union’s second space flight, ‘I was looking around very attentively, but I did not see anyone. I did not detect either angels or gods . . . I don’t believe in God. I believe in man – his strength, his possibilities, his reason.’ Khrushchev had put Titov’s words into Gagarin’s mouth during a speech the President made in support of the Soviet state’s antireligion campaign, presumably because they would seem more forceful coming from the more famous Gagarin. When John Glenn was asked for his reaction to Gagarin’s supposed comment, Glenn pointed out that God, being everywhere, would be no closer in orbit than he was on Earth: ‘God . . . will be wherever we go,’ he said. In the years that followed, almost every returning astronaut would be asked to respond to Titov’s observation.

That the space race mirrored the Cold War’s fight for technological supremacy was clear; that it also mirrored the Cold War’s battle over belief was less obvious. Khrushchev had once ridiculed America’s inability to launch anything other than ‘grapefruit’ satellites; now he was using the space race to ridicule America’s God. That God might be more apparent in space than on Earth was crude theology, but Khrushchev had nevertheless thrown down a theological challenge. From this unpromising opening salvo a subtler debate would develop; not just between the USSR and America, but within America itself. Khrushchev’s taunt would highlight just how little clarity there was about the place of religion in America.

In a landmark case of 1947 – Everson v. Board of Education – the desire of the Founding Fathers to keep church and state apart in America had been affirmed. In his ruling, the Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black stated that laws must not ‘aid one religion . . . or prefer one religion to another . . . In the words of Jefferson, the [First Amendment] clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect “a wall of separation between church and State” . . . That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach.’ But during the 1950s, the separation had not always been clearly adhered to. In 1954 the words ‘one nation’ were changed to ‘one Nation under God’ in the Pledge of Allegiance. ‘From this day forward,’ President Eisenhower said, ‘the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty.’ The year before – the year he had been sworn in as President – Eisenhower chose to be baptized into the Presbyterian Church. He had been raised into a family of Jehovah’s Witnesses, or perhaps they were Mennonites; opinion seems to be divided. He renounced the family faith before he joined the army, but had now re-embraced faith in a different form. Just as confusing was the change in 1956 of the nation’s motto. It had been E pluribus unum (One out of many) since 1782 but was now changed to ‘One Nation Under God’. How were these changes supposed to square with the idea that church and state were separate? Judgments around the country, too, seemed to show a lack of clarity in law. In New Jersey a school lunchtime blessing – God is great, God is good, and we thank Him for this food – had been ruled illegal because it asked for divine intervention. But for some reason the Lord’s Prayer was ruled non-sectarian and was suggested as an alternative, until that too was opposed, and at last silence was put forward as an option. But then it all became decidedly Jesuitical: what if the children were to say grace silently to themselves, and then what would be the point of a silence during which you were to think of anything but God?

Whether or not the constitution mandated a separation of church and state had again become a hot issue during Kennedy’s Presidential campaign. As a Roman Catholic he had needed to reassure the electorate that his faith would play no part in his role as President. He repeatedly asserted during his campaign that church and state were separate, and would remain so if he were elected. In a speech he gave in 1960, he said that because he was Catholic and no Catholic had ever been elected President, ‘the real issues’ had been obscured during his election campaign: ‘So it is apparently necessary for me to state once again – not what kind of church I believe in, for that should be important only to me – but what kind of America I believe in.’ He went on to reassert that he believed ‘in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute; where no Catholic prelate would tell the President – should he be Catholic – how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote; where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference, and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the President who might appoint him, or the people who might elect him.’ In an address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association in September 1960, he said that he believed ‘in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish . . . For while this year it may be a Catholic against whom the finger of suspicion is pointed, in other years it has been – and may someday be again – a Jew, or a Quaker, or a Unitarian, or a Baptist.’ Or an atheist, he did not add.

Some Protestant American churches were set against a Catholic President and were publishing anti-Kennedy literature. The IRS had made it clear that those churches risked losing their tax exemption status. The Revenue Service’s action showed that it was indeed possible by law to keep church and state apart.

During the year of Kennedy’s election, an American atheist by the name of Madalyn Murray filed an action against her son’s school, which had expelled her atheist son for refusing to attend the school’s daily prayer meeting. By 1963 the case – Murray v. Curlett – had made its way to the Supreme Court. On 17 June, just over a month after the last Mercury flight, the state make its strongest ruling yet in its affirmation of the separation of church and state. Eight of the nine Supreme Court justices ruled in Madalyn Murray’s favour, bringing to an abrupt end the practice of religious observance in the country’s public schools (called state schools in the UK). Madalyn Murray had set out her life’s work.