In protest against what he considered to be Roosevelt’s warmongering, Charles Lindbergh had resigned his commission. He had briefly considered spending a year or two in contemplation, but now that America had entered the war, he regretted his hasty decision and realized that it was his duty to fight. He wrote to his friend General Hap Arnold, Chief of the Army Forces, offering his services. Arnold made the offer public. The New York Times was supportive, the rest of the press less so. Roosevelt personally intervened to prevent Lindbergh from re-enlisting. When, in 1942, the War Department allowed Lindbergh to work with Pan Am on their war projects, the White House was furious and put pressure on companies that had government contracts not to employ him. When Henry Ford offered Lindbergh a job in Detroit – where his factory, then the largest ever built, was making B-24C bombers at the rate of one an hour – even the Administration couldn’t stand in Ford’s way.

Lindbergh thought the B-24C was mediocre. After a number of test flights, he suggested some improvements. The Russian-born American plane designer Igor Sikorsky once told a woman at a dinner party that Lindbergh could not only fly any plane but could pinpoint and fix any design flaw on the drawing board. ‘You mean to say that all of your test pilots can’t do that,’ the woman responded. ‘None of them can,’ Sikorsky told her. ‘They can fly anything, and when they bring it down they can tell me how it handles, but they don’t know why it behaves a certain way. Charles will know where the mistake is and have a suggestion about correcting it.’ After some months working with the Ford Company, Lindbergh renegotiated the deal, deciding that he was unsuited to the work, and reduced his connection to that of part-time adviser.

For two weeks in September 1942 Lindbergh offered himself up as a guinea pig to Dr Walter M. Boothby, who was studying the effects of high-altitude flying at the Aeromedical Laboratory in Minnesota. New planes were being designed that could fly to 40,000 feet, but no one knew how pilots and crew would cope quickly descending from those altitudes, or what happened to reaction times at low air pressures and low oxygen levels. Several times he was tested to unconsciousness. Lindbergh used the results of the research to test and redesign existing procedures used during emergency parachute jumps from high altitudes. Lindbergh also taught young fighter pilots how they could reach higher altitudes, and engaged with them in mock aerial battles, but what he really wanted was to see active service. In January 1944 he was asked by United Aircraft to carry out research in the South Pacific on two planes that he had been testing for the company: the F-4U Corsair and Lockheed P-38 fighters, both of which had been adapted to carry bombs. By April he was in New Guinea, officially as a civilian technician and observer. When he wrote to Colonel Charles MacDonald, Commander of the 475th Fighter Group of the Fifth Air Force based in the Far East, for permission to go on a bombing raid, MacDonald’s deputy said: ‘My God! He shouldn’t go on a combat mission. When did he fly the Atlantic?’ MacDonald said, ‘I’d like to see how the old boy does.’ The old boy was 42. Lindbergh was not given formal permission, but an unspoken arrangement was reached that the military would turn a blind eye. Coincidentally, somewhere over the Mediterranean, Saint-Exupéry was also flying a P-38, and at 43 was by far the oldest pilot in the service.

It soon became apparent that when Lindbergh flew the P-38 his fuel consumption was much lower than that of his colleagues, pilots around half his age. News of his achievement reached the ear of General MacArthur himself, who asked to see him. MacArthur said it would be a gift from heaven if the P-38 could be flown more efficiently. Lower fuel consumption meant longer flying time. Combat missions could be extended. Lindbergh was told to teach his fellow pilots how to fly as he flew. Because of Lindbergh, six- to eight-hour missions became ten-hour missions. The enemy was surprised deeper into its territory. ‘Lindbergh was indefatigable,’ MacDonald wrote. ‘He flew more missions than was normally expected of a regular combat pilot.’

On 8 September 1944, Lindbergh dropped a 2,000lb bomb over Wotje island, one of the Marshall islands. In his diary he wrote, ‘so far as we know, this is the first time a 2,000lb bomb has been dropped by a fighter’. Four days later he broke his own record and from an F-4U dropped a 2,000lb and two 1,000lb bombs. From the air he saw one of his 2,000lb bombs wipe out a Japanese emplacement on the ground: ‘One moment the earth below me lay motionless; the next, a column of earth and dust appeared like magic in the air. On the razor-edge of time, an unknown number of human lives and bodies vanished by my pressing the red button on a control stick.’ Such senseless death challenged his adherence to the law of natural selection. Evolution had used death as a way of advancing the fittest, yet highly trained airmen were among the first to die in war: ‘No selection resulted from man’s atomizing of his cities.’ On another mission, flying over the coastline of Japan, he saw a naked man wandering on the beach. Lindbergh had been ordered to kill anyone he saw on the ground. As he drew closer the man did not speed up: ‘I should never have forgiven myself if I had shot him – naked, courageous, defenseless, yet so unmistakably a man.’

On 12 April 1945, after 4,422 days in office, and just a few weeks shy of the formal end of the world war, FDR died. He remains the only American president to have served three full terms, and the only one to have been elected to serve a fourth term. With no objections now put in his way from the White House, on 11 May, three days after VE Day, Lindbergh was on a navy transport plane to Germany, as consultant to the United Aircraft Corporation and as part of a navy technical mission to learn as much as possible about German developments in high-speed aircraft.

Lindbergh was invited to fly the plane but mostly he slept: ‘One might as well sleep,’ he wrote in his journal, ‘for the modern military plane is usually uninteresting from the passenger’s standpoint – high above the earth – often above the clouds, so that no details can be seen (even if bucket seats and badly placed windows didn’t make it so difficult to see anyway). Every year, transport planes seem to get more like subway trains.’ Among the places Lindbergh visited as he made his way across Germany was Hitler’s ‘fabled mountain headquarter’ near Berchtesgaden. He thought the view one of the most beautiful he had ever seen. During the afternoon of Sunday 10 June, Lindbergh arrived at Mittelwerk to inspect the underground factory where von Braun’s V-2 rockets had been manufactured.

In the chaos of the last weeks and days of the war, thousands of concentration camp prisoners had suddenly been dumped at the Mittelbau-Dora camp. On the nights of 3 and 4 April an already hellish situation was made worse when Allied planes bombed the camp, which from the air had been mistaken for a munitions plant. A massive evacuation of the camps around Mittelwerk – Dora, Nordhausen and the two smaller camps, Ellrich and Harzungen – began the following day. Several thousand prisoners were sent on death marches. Many thousands more were packed onto trains and sent to Bergen-Belsen. There were mass hangings, and mass shootings. Paul Tregman, a survivor of Ellrich, described one such train journey to Bergen-Belsen that took place early that April:

For six days our train, consisting of forty-some cars, dragged nearly 4,000 prisoners along a route which could normally be covered within seven hours. One hundred and thirty persons were crammed into each car, pressed together like sardines in a can and reeking like rotten garbage. One SS man and one Kapo were assigned to each car to keep these pigsties in order. A tiny window heavily barred, let in a miserly bit of fresh air. No one was allowed to get off the train at any of the stops, and there was no place for the prisoners to relieve themselves. If a passenger finally lost control of his bladder or bowels, the Nazi overseers would beat him till he bled and toss him from the moving train, and the SS man would fire a bullet after him to make sure he died.

By the end of the war it is estimated that out of some 60,000 prisoners who were held at the camps around Mittelwerk, 25,000 perished. There may have been many more whose lives and deaths were not recorded. More than half of the 25,000 were killed en masse in the last days of the war by SS officers aware that the American military was close by and that this was their last opportunity.

By 10 April most of the camp guards had left the region. At 2.30pm on that day some of the remaining prisoners at Camp Dora saw a solitary figure, an American soldier, exchanging fire with one of the last fleeing guards. At 4.00pm the American soldier, Private John Galione, arrived at the camp gates.

Five days earlier John Galione had complained to his sergeant, Leonard Puryear, that there was a terrible smell, and that he and some of his fellow soldiers wanted to put together a search party to go and investigate. There had been rumours that there was a labour camp in the area, and perhaps that was what they were smelling. Sergeant Puryear refused permission; the risk of ambush was too great. German soldiers were scattered everywhere across the region.

That night, at around 9pm, Galione decided to leave the encampment on his own. On a hunch, he decided to start walking along nearby railroad tracks. He thought he had smelled that same smell before sometimes when they were passing German trains. He left word that he would return soon, and that if their sergeant noticed he was missing to tell him that he wasn’t deserting but going on a mission. He thought he would be back by 12.30am at the latest, but he just carried on walking; first for hours, and then for days. He had to drag himself forward; one leg had been shot at some weeks earlier and had not yet fully healed. He said he never slept, for fear of ambush; he rested every so often, leaning against a tree for an hour, and then returned to the tracks. He said that energy came to him mysteriously. When he felt most like giving up it was as if hands came out of nowhere and pressed him on his lower back, literally propelling him forward. After more than four days Galione arrived at the mouth of a cave, where he found a railway truck filled with dead bodies. He was spotted by a German officer and they began to exchange fire, but the officer was clearly on his way somewhere and soon disappeared. Galione had walked 110 miles due west from his company’s base in Lippstadt and had arrived at Mittelwerk.

An hour or so later he made a horrifying discovery. Pressed against the wire fence of what was clearly some kind of prison were dozens of emaciated bodies, scarcely breathing, and behind them piles of dead bodies. The gates to the encampment were padlocked shut. The sun was setting. Again fearing ambush, he left the camp intending to return in the morning with help.

By good fortune Galione happened upon two soldiers from his own 104th Infantry Division ‘Timberwolves’ (motto ‘Nothing in hell can stop the Timberwolves’). They were working on a broken-down jeep, which Galione offered to fix. The three returned to the camp and forced their way in. On the other side of the gates they saw what Galione later estimated were a thousand dead bodies, and hundreds of people clearly barely alive, some taking no more than two breaths a minute. Galione said that some prisoners were so emaciated he could see their spinal columns through their stomach muscles. The three GIs decided that their best course would be to drive back to Galione’s detachment at Lippstadt and get help. It took three hours to cover the distance Galione had taken four days to walk.

Sergeant Puryear radioed the Third Armored Division who were stationed closer to the camp and told them that something unusual was going on nearby and that they should investigate. Out of guilt that he had not acted sooner, Puryear asked Galione to keep the details of the discovery quiet. Galione agreed and kept his word for decades. In the 1960s his daughter – sensing that he had a story to tell – pressed her father to tell it. He said he would one day, but not yet. He finally told her in the 1990s. Most accounts of the relief of the camps around Mittelwerk begin with the mysterious message relayed to the Third Armored Division. John Galione’s account has not been officially sanctioned by the US Army but has been confirmed by a number of Dora survivors, and in an affidavit signed by Leonard Puryear.

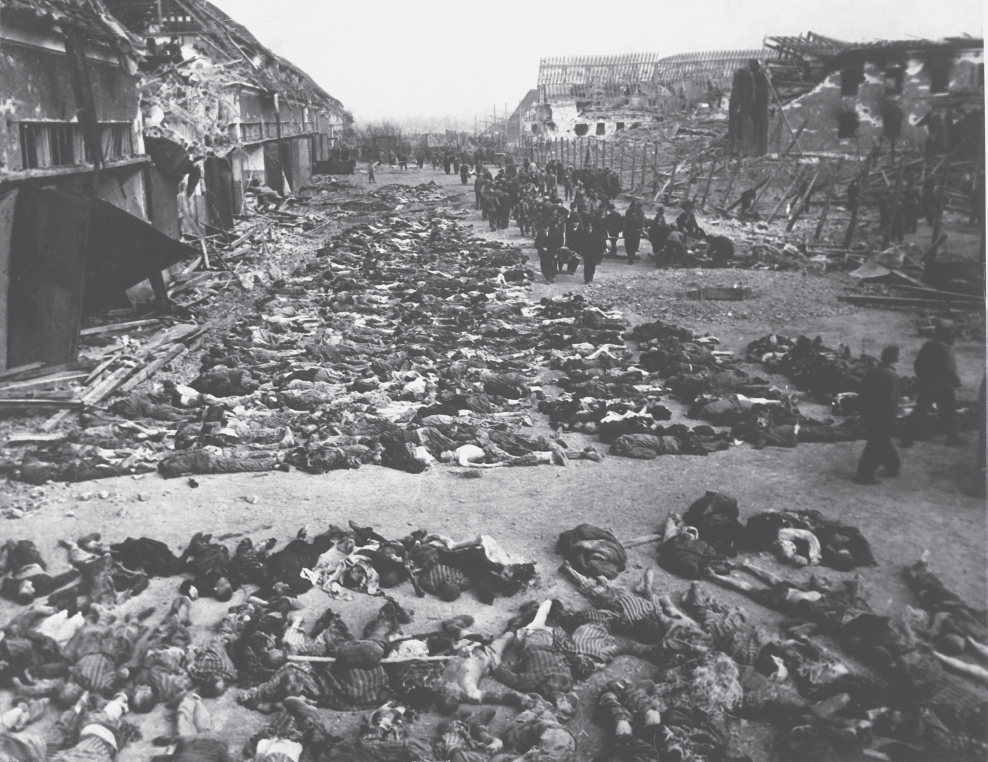

On their way to camp Dora, Combat Command B of the Third Armored Division stumbled by accident on the camp at Nordhausen. Some of the most shocking images and footage of the conditions inside Nazi concentration camps were taken by US soldiers soon after they first entered Nordhausen on 11 April 1945. One soldier, Sergeant Ragene Ferris, described how he had come across a crater made after the Allied bombing of 5 April filled with bodies. At the bottom of the pile were three people who had been struggling for five or six days to get out, ‘but the weight of other bodies on them had been too much for their starved emaciated bodies’.

Corpses at the Nordhausen concentration camp

Local civilians were forced to dig a long trench grave to bury the many dead from the camps around Mittelwerk

Back at Camp Dora, Galione set out in search of food, forcing a local German woman at gunpoint to slaughter two pigs. Half a century later he told his daughter how, again, some superhuman effort had been required of him to drag each carcass back to the camp.

It was not long before American soldiers found their way into the network of tunnels at Mittelwerk that branched deep into the Harz mountains. One officer reported that being inside the tunnels was ‘like being in a magician’s cave’. Work had stopped there only the day before; eerily, the electric power was still on, the ventilation system still humming. When Galione had first entered camp Dora the day before, the crematorium there was still smoking.

The sheer scale of the V-2 operation came as a shock. Special Mission V-2 was quickly orchestrated from Paris by Colonel Holger Nelson Toftoy, Chief of the Army Ordnance Technical Intelligence, to recover as many V-2s as possible. A hundred complete V-2s were retrieved from the tunnels and rapidly broken down into their constituent parts. In the next few months, dozens of trains took the components from Mittelwerk to Antwerp, where they were boarded onto 16 Liberty ships destined first for New Orleans.

By the time Lindbergh arrived at Mittelwerk in June, the operation was well underway. There were hundreds of V-2 parts scattered around the grounds of the vast encampment: ‘nose cones, cylindrical bodies, and big Duralumin fuel tanks . . . A number of tail sections, shining and finned, were standing on end like a village of Indian teepees.’ Some of the discarded parts had been made into bizarre makeshift shelters. Passing through the still-stinking grounds Lindbergh entered the tunnels, even now brightly lit. In otherwise empty offices he saw discarded identity cards strewn on the ground, thousands of them. In the heart of the mountain he came upon what looked ‘like a giant grub’, an entire gleaming V-2 rocket, in the process of being dismantled by Allied experts. The evidence of past efficiency and present desolation was jolting: ‘The Nordhausen establishment seemed far from the earth I knew, as though I had ridden one of the missiles it produced and stepped out on a strange and terrible planet.’ In his head rang the words of a man who had directed them to the tunnels. He had told them that for the workers the only way out had been as smoke.

A 17-year-old Polish survivor, still wearing a striped concentration-camp uniform, showed Lindbergh around the site. The boy looked down and Lindbergh followed his gaze. They were standing at the edge of a pit 8 feet long and 6 feet wide filled to overflowing with ashes and chips of bone. There were two more pits nearby. Lindbergh guessed that the pits might be 6 feet deep. ‘Of course, I knew these things were going on,’ he wrote in his journal the same day, ‘but it is one thing to have the intellectual knowledge, even to look at photographs someone else has taken, and quite another to stand on the scene yourself, seeing, hearing, feeling with your own senses.’ Tellingly, he now writes about his former belief in American exceptionalism in the historic past tense – ‘I had considered my civilization as everlasting. It was too scientific, too intelligent, to break down as earlier civilizations had’ – before moving into the present tense to describe what he witnessed at Nordhausen – ‘This, I realize, is not a thing confined to any nation or to any people . . . What is barbaric on one side of the earth is still barbaric on the other . . . It is . . . men of all nations to whom this war has brought shame and degradation.’

At the end of 1944 Wernher von Braun told a colleague that he had already packed his bags and that he intended to offer his services to America: ‘And then I will build my space rocket.’ On the last day of January 1945 General Kammler gave orders to begin evacuating Peenemünde. The Soviet army was advancing west across Prussia and Kammler realized that it might be expedient to have a bargaining chip. He rounded up 500 scientists and engineers, von Braun prize among them, and put them on a well-appointed train to Nordhausen, 250 miles to the south. How different were the trains crisscrossing Germany in those last weeks of the war! Kammler placed SS Major Kummer in command with orders that he was to shoot his charges rather than let them fall into enemy hands. The party arrived in Nordhausen in March.

On 17 March von Braun was on his way by car in a last attempt to try and raise more money for V-2 production. En route his driver fell asleep at the wheel while doing 60 mph. They could both have been killed. As it was, von Braun suffered multiple fractures to an arm and shoulder. The fracture knitted badly. In great pain von Braun returned to Nordhausen.

On 19 March Hitler issued his so-called Nero Decree, which ordered the destruction of everything that might be of value to the Allied forces. Von Braun was ordered to destroy all the records and blueprints of the Aggregat rockets. Instead he hid 14 tons of documentation in a mine and had the entrance dynamited shut. Von Braun, too, had realized that a bargaining chip might come in useful later.

On 1 April the 500 Peenemünders, along with 100 SS officers, were put on another train and sent to Oberammergau in the Bavarian Alps, where, supposedly, the Nazis were going to make a last stand. Oberammergau is most famous as the site on which an anti-semitic passion play has been performed since 1634. Henry Ford saw the play performed in 1930.

Once they had arrived it was clear that something needed to be done about von Braun’s arm. He was sent to a hospital – the nearest one was 50 miles away – where his arm was re-broken, without anaesthetic. After two weeks’ recuperation he returned to the group’s hideaway with his arm in a cast. Von Braun was billeted with his younger brother Magnus and Dornberger at a ski resort in Oberjoch, not far from Oberammergau. Major Kummer had been persuaded that they would be less of a sitting target if the group was split up and distributed about the region. In fact von Braun was less worried about the enemy than he was about the unpredictable Kammler, who had disappeared. His return was feared each day. If Kammler thought the engineers might be about to fall into enemy hands there was no knowing what he’d do.

By 24 April Soviet forces had surrounded Berlin. In the next few weeks 325,000 Berliners would be killed. It looked as if the German engineers should prepare themselves – if they were lucky – for a Russian future.

Von Braun was listening to Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony on the wireless when the performance was interrupted to announce the death of the Führer. ‘Hitler was dead,’ von Braun later wrote, ‘and the hotel service was excellent.’ Dornberger persuaded their SS captors that their best bet now was to burn their uniforms and ID cards and offer themselves to the Allied forces as POWs. News came through that there were American soldiers close by. Magnus, who spoke the best English of any of them, was sent off on a bicycle to search them out.

The 44th Infantry Division of the American Seventh Army had arrived in the region just the day before. They were as keen to find von Braun’s party as von Braun’s party were to find them. When Magnus came upon them he called out: ‘My name is Magnus von Braun. My brother invented the V-2. We want to surrender.’ He had to spend half an hour trying to persuade disbelieving army personnel that the V-2 engineers were up in the mountains nearby. He was given a safe conduct pass and told to bring back evidence.

Dornberger and von Braun put together an advance party of around ten. Von Braun said later that they hadn’t known what to expect when they arrived. In the event ‘they immediately fried us some eggs’. One member of the army division later said of von Braun that he treated the US soldiers ‘with the affable condescension of a visiting congressman’. He posed for endless photographs with GIs: ‘He beamed, shook hands, pointed at medals and otherwise conducted himself as a celebrity rather than a prisoner.’ He apparently boasted that if they had had two more years the V-2 would have won the war for Hitler. One GI remarked: ‘If we hadn’t caught the biggest scientist in the Third Reich, we had certainly caught the biggest liar.’ During that night a member of the kitchen staff, a Pole, was intercepted as he attempted to shoot the sleeping party of German rocket engineers.

First Lieutenant Charles Stewart, who had granted Magnus safe conduct passes; Herbert Axsted, Dornberger’s chief of staff; Dieter Huzel, Wernher von Braun’s assistant; Wernher von Braun; Magnus von Braun; Hans Lindenberg, a V-2 engineer

Just a week after Germany had formally surrendered, von Braun wrote an eight-page report for his interrogators translated as ‘Survey of Development of Liquid Rockets in Germany and their Future Prospects’. He set out his dream of space exploration. He described rockets that could travel between Europe and America in 40 minutes. He wrote of a future in which the ‘whole of the Earth’s surface could be continuously observed’. He imagined how we might be able to control the weather (a presumed ability often associated with the deranged). Sunlight reflected from a giant mirror orbiting in space could be beamed down to where it was needed on Earth. He envisaged travel to the moon. He also showed himself to be politically astute (or was it opportunistic?): ‘We are convinced that a complete mastery of the art of rockets will change conditions in the world in much the same way as did the mastery of aeronautics.’ Von Braun was convinced that war with Russia was inevitable, and that whoever first mastered rocketry would gain the upper hand. He seized this first, early opportunity to propagandize on behalf of space travel: ‘When the art of rockets is developed further, it will be possible to go to other planets, first of all to the moon. The scientific importance of such trips is obvious.’ And yet it would not be obvious to everyone; in the immediate years that followed the war von Braun would have to spell it out repeatedly.

Colonel Toftoy was the man in charge of deciding who, out of the thousands of German scientists and engineers interned in Germany, should be cleared to start a new life in America. Von Braun was top of the list and was held under armed guard to keep him out of Soviet hands. The British asked that von Braun and Dornberger be handed into their custody, they said for a few days. The pair were driven across London and shown the devastation their missiles had caused. It took some pressure from the US War Department before the British military was willing to return von Braun into American custody. The British held on to General Dornberger for two more years, not because they wanted his technical knowledge – which was extensive – but because they wished to see him tried at Nuremberg as a war criminal. They had really wanted SS General Kammler, but he was nowhere to be found. Dornberger said he had heard that he died in the last days of the war in Prague, killed at his own request by a fellow SS officer, but neither where nor when he died is known for certain. In 1947, as it became clear that the case against Dornberger was weak, he was released. Dornberger then made his way to the States.

Von Braun had attempted to argue that all of the group of 500 Peenemünders should be given clearance – he always tried to push his luck. He was told he could choose 100, and in the end 117 Peenemünders made the list as part of Operation Overcast, later renamed Operation Paperclip because a paperclip was attached to the file of those selected.

Von Braun and six others prominent rocket engineers were the first of the 117 to arrive in America, landing at Fort Strong in Boston Harbour on 20 September 1945 from where they were moved to Fort Bliss, an army base near El Paso, Texas. By February 1946 most of their colleagues had arrived. The men were designated DASE, employees of the Department of the Army Special Employees. Only towards the end of that year was their presence in America made public. Einstein wrote to President Truman: ‘We hold these individuals to be potentially dangerous carriers of racial and religious hatred.’

By the time von Braun arrived in America, Goddard had been dead a month. When peace came, Harry Guggenheim agreed to start funding Goddard again but Goddard died in August of throat cancer. He lived just long enough to inspect one of the first V-2s to arrive in America from Mittelwerk; and just long enough to complain, one last time, that his ideas had been stolen. The V-2, he said, was clearly based on his own designs. The National Geographic Society in Washington DC issued a statement in support of Goddard’s allegation. Lindbergh told the press that he agreed and that the V-2 had plainly infringed American patents. He said that America ignored its visionary geniuses. The Germans had indeed been in touch with Goddard before the war, and had used whatever they could find from published papers, but you only had to look at the thing to see that the V-2 was technically way ahead of anything America could then achieve. V-2s had soared to 60 miles or more above the Earth’s surface and broken the sound barrier: Goddard’s rockets barely, and rarely, reached altitudes of 2 miles.

Goddard’s last rocket launch before America entered the war had used a turbo-pump and possessed a more powerful engine than any he had used before, but the rocket nevertheless crashed soon after takeoff. The pumps worked well, but it was too little too late. During the war years, with Lindbergh away supporting the war effort, Goddard’s work was curtailed. Both Guggenheim and Lindbergh attempted to interest the military in Goddard’s rockets, but with little success. One meeting happened to coincide with the second day of the evacuation from Dunkirk; military minds were elsewhere, and anyway few in the military thought it likely that missiles would be used in this war. The navy offered Goddard a crumb: he was invited to work on a solid-fuelled jet engine they were developing, the JATO (jet-assisted take off) engine. It would enable a heavily loaded aircraft to take off from a short runway, like ‘hitching an eagle to a plow’ as one commentator put it. It was basically an adaptation of Goddard’s pump rocket from a vertical to a horizontal plane. Goddard worked on refining the engine until the end of the war. It was almost perfected when the navy switched to a different technology.

Goddard was still defending his territory less than a year before his death. On 19 June 1944 Edmund Wilson gave Willy Ley’s book Rockets a favourable review. Goddard wrote to the paper claiming that the Germans, as far as rocket science was concerned, had not been first in anything. Three days later the first V-1s struck London, and soon after the first V-2s.

In the report Lindbergh wrote for the navy on his return from Mittelwerk, he implied that but for some blunders made by Nazi High Command, the V-2 would surely have won Germany the war. This was nonsense. The Germans had banked on the wrong weapon, as Churchill perceptively pointed out. If they had encouraged Heisenberg to develop the atom bomb, history might have been rewritten. Even if von Braun had been able to perfect his A-9 winged version of the V-2 and his A-10, a souped-up version of the A-9, it is doubtful if Germany could ever have got the upper hand. The A-9 would have put New York within striking distance when fired from France, but the force of the atom bomb spoke for itself. So devastating was its effect when used by America at the end of the Second World War that it has never been deployed in war since.

The British had been promised 50 of the 100 recovered V-2 rockets but in the event all of them were shipped to America. Nevertheless, on 22 June 1945 General Eisenhower agreed that a British operation should attempt, right away, to build and fire some V-2s. The charmingly named Operation Backfire came into being. With most of the salvageable parts en route to America, the group had to scrabble about to find what they needed, but by September German engineers had eight V-2s in near-readiness for firing from the launch site at Cuxhaven in north Germany. Early in October, and after a couple of stalled attempts the day before, the first launch went without a hitch. The Germans and their British guards were jubilant. Speeches were made on both sides. A second launch two days later was also a success. A third launch – named Operation Clitterhouse, and set for 15 October – was to be for the benefit of observers from America, Russia, France, the UK, and the press. By this time von Braun had arrived in America, but among those gathered to witness what turned out to be yet another flawless flight were Russian rocket designers Sergei Korolev and Valentin Glushko.