For a couple of weeks from the middle of October 1962, the world came close to all-out nuclear war. The Soviets denied that they had a missile base in Cuba and were still denying it on 25 October. The public at the time was unaware that America had missiles based in Italy and Turkey directed at the Soviet Union. Two days later Soviet submarine captain Valentin Savitsky ordered a nuclear torpedo to be ‘made combat-ready’. China aligned itself in support of Russia. The world stood on the brink. Kennedy told his aides that the chance of war was between one in three and even. Khrushchev blinked. He agreed to remove his missiles from Cuba, and America agreed to remove theirs from Italy and Turkey, though America’s side of the deal was never made public. Khrushchev looked weak. His power at home never recovered.

And yet even by the time Project Mercury came to an end in May 1963, the perceived wisdom was that the Soviets were still way ahead in the space race. How much of this was propaganda from the likes of von Braun, who had an interest in promoting the idea that America was falling behind, or of Khrushchev, in whose interest it was that Russia should be seen to be ahead, will no doubt be debated by historians for decades to come. Even the Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, wondered if there was something wrong with America as a whole that it could be so easily beaten by the USSR. He thought the country’s industries should become more centralized, to the benefit of national strategic goals, as seemed to be the strategy in Russia. NASA’s director, James Webb, shared some of the same reservations. They wondered, as Eisenhower had, if perhaps the country had ‘over-encouraged the development of entrepreneurs and the development of new enterprises’. In a letter to his predecessor, Dr T. Keith Glennan, Webb wrote: ‘My own feeling in this and many other matters facing the country at this time, is that our two major organizational concepts through which the power of the nation has been developed – the business corporation and the government agency – are going to have to be re-examined and perhaps some new invention made.’

When Webb offered George Mueller – then head of research and development at a large electrical engineering company – a top job at NASA, Mueller said he would accept it only if he had a free hand to restructure the organization, a vision that chimed with Webb’s call for organizational reinvention. Mueller arrived on 1 September 1963 and soon concluded that a lunar landing would not be achieved by the end of the decade without wholesale reform of the way NASA worked. Mueller decided that Project Apollo’s booster rocket Saturn V was taking too long to develop.

Project Apollo’s first official mission had been the launching of the first Saturn I rocket live on TV on 27 October 1961. Standing 162 feet tall and weighing 460 tons, it produced 1.3 million lbs of thrust. It was the biggest and most powerful rocket ever launched at the time, 10 times as powerful as the rocket that had put the Explorer satellite into orbit. By the time of the launch, NASA had already requested a more powerful version, the Saturn IB, which would produce 1.6 million lbs of thrust. Shortly after the launch, Saturn V was announced as the launch vehicle of the manned missions to the moon. It would produce over 7.5 million lbs of thrust. (The key Saturn rockets are Saturn I, Saturn IB and Saturn V. There doesn’t appear to have ever been, for example, a Saturn IV. There was an S-IV, the designation given to the second stage of the Saturn I, which I mention only to illustrate how baroque, or seemingly arbitrary, the art of rocket classification is.)

Instead of incremental testing, which was von Braun’s preferred way, Mueller insisted on all-up testing of Saturn V; meaning a fully fuelled rocket should be flown as soon as possible rather than as a series of flights using dummy stages in varying configurations. Von Braun was by nature risk-averse, or more riskaverse than Mueller anyway, but he was persuaded. And yet von Braun was also perfectly capable of making his own grand gestures. At one point in the development of Saturn V he apparently casually told the engineers to increase the number of engines from four to five. His power may have been limited compared to Korolev’s, but this kind of authority would be inconceivable today when, across all businesses, autonomy has been ceded to group decision-making.

For Webb the lunar mission hadn’t even been a priority, but it was for Kennedy. Publicly Kennedy had declared that travelling to the moon was ‘in some measure an act of faith and vision, for we do not know what benefits await us’, but when Webb started talking about the benefits of Apollo to science, Kennedy got irritated. If it was about science, then why, Kennedy asked at one meeting, ‘are we spending seven million dollars on getting fresh water from saltwater, when we’re spending seven billion dollars to find out about space?’. Webb said that Apollo should be about pre-eminence in space, not just one short-term project. Kennedy said: ‘We’ve been telling everyone we’re pre-eminent in space for five years and nobody believes it!’ From now on – Kennedy made it very clear – NASA’s main goal was to get three men to the surface of the moon and safely back again. Everything else was peripheral. Webb, von Braun and others at NASA were disappointed. Von Braun had for years promoted the idea of a space station, and of manned missions to Mars. All these secondary long-term goals were now to be put aside for the short-term, if ambitious, goal that was Project Apollo. The largest casualty was the air force’s rival to Apollo, the X-20 Dyna-Soar (another of those painful appellations), which from its inception in 1957 to the time it was cancelled at the end of 1963 had cost over $600 million. The Dyna-Soar was a rocket/plane hybrid. It was designed to be launched into space vertically, powered by one of the air force’s Titan rockets, but when it returned to Earth it would glide and land on an airfield. That’s how the Space Shuttle would work, but the Dyna-Soar (unlike the dinosaur) was ahead of its time.

How to land on the moon was a key problem that NASA needed to solve. But even before a manned mission to the moon had been planned, NASA had sent out a series of probes to test their ability simply to find the moon; that is, to test their ability to calculate the necessary trajectory. Rangers 1 and 2 failed to escape Earth orbit. Ranger 3 missed the moon by 22,000 miles. Ranger 4 missed the moon by 450 miles and suffered electrical failure. Ranger 5 also failed to find the moon. Ranger 6 was disabled at launch. Finally, five years into the project, in 1964, Ranger 7 crashed into the moon, sending back sharp TV images before it did so. How to land softly on the moon was a challenge yet to come. As to landing men softly onto the moon’s surface, it was clear that however it was going to be achieved it would not be by gliding them down in a vehicle like the X-20. An alternative direct approach would be to launch a rocket whose upper stage could somehow back up and land on the moon stern first. If that approach had been taken, Kennedy’s date would probably have been missed by a decade. Only now has that technology been developed. The preferred method of landing was called EOR (Earth Orbital Rendezvous), an approach not dissimilar in principle to the method von Braun described in The Mars Project. The idea was to launch several small rockets – much easier than launching one large rocket – and assemble the moon landing craft in Earth orbit. Only modest thrust would then be required to get it out of Earth orbit and on a trajectory to the moon.

But there was another solution. Tom Dolan, an engineer at the firm Vought Aeronautics, brought up the possibility of LOR (Lunar Orbital Rendezvous), an idea that was being touted by John C. Houbolt, an engineer at the Langley Center. Why not go all the way to the moon and then launch the lander from moon orbit? That way the moon lander could be much lighter than anything sent directly to the moon from out of Earth orbit.

Von Braun preferred the Earth orbital solution. He thought it was safer and provided a long-term future, as did Max Faget, the designer of the Mercury capsule. The danger with LOR was that if the rendezvous failed, there was no way to get the stranded astronauts back. Kennedy’s science adviser, Jerry Wiesner, was against it too: ‘They’re risking those guys like mad,’ he said. But, when he saw which way the wind was blowing, von Braun – always a team player – stepped into line and accepted the lunar orbital solution. Wiesner was furious. Kennedy went around saying, ‘Jerry’s going to lose. It’s obvious. Webb’s got all the money, and Jerry’s only got me.’ Though the rendezvous would take place in lunar orbit, the technology and techniques would need to be tested out first in Earth orbit. Project Gemini, a sequence of 12 two-manned flights, was inserted between Mercury and Apollo to ensure that two craft could meet up and dock in orbit. If two capsules could meet in Earth orbit then there was no reason to suppose that they could not do so in lunar orbit.

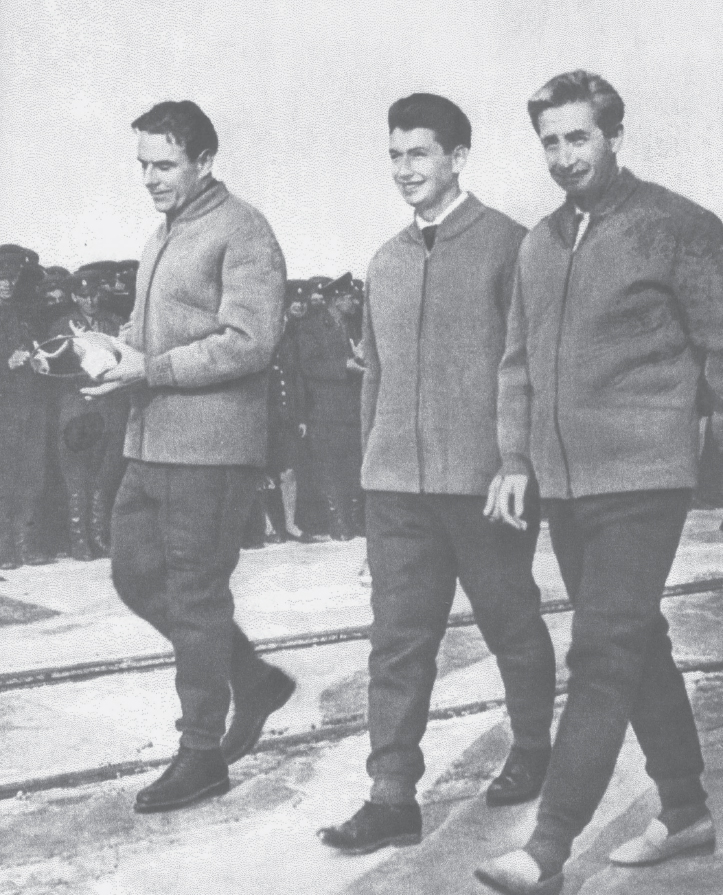

Project Gemini had 27 astronauts to draw from: the Mercury Seven and two later intakes. Late in 1962 NASA had introduced a further nine astronauts to the world. Unimaginatively, they were dubbed the New Nine: Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Pete Conrad, Jim Lovell, Jim McDivitt, Elliot M. See, Tom Stafford, Ed White and John Young. Lily Koppel in her book on the astronaut wives writes that ‘NASA had a protocol officer conduct a New Nine orientation, where he prattled on about how astronauts needed a good breakfast before flying off to work . . . Feed him well. Praise his efforts. Create a place of refuge.’ All just as it had been before when they were officers’ wives. Apparently some of the New Nine wives treated the Mercury Seven and their wives like royalty, called them Sir and Ma’am.

New Nine astronauts: Back row: See, McDivitt, Lovell, White and Stafford. Front row : Conrad, Borman, Armstrong and Young

A year later NASA introduced a third intake of astronauts into the programme, NASA Astronaut Group 3. They don’t seem to have been given a nickname. There were 14 of them: Buzz Aldrin, Bill Anders, Charlie Bassett, Al Bean, Gene Cernan, Roger Chaffee, Mike Collins, Walt Cunningham, Donn Eisele, Theodore Freeman, Dick Gordon, Rusty Schweickart, Dave Scott and Clifton Williams.

Kennedy had earmarked 29 January 1964 as the day America would conclusively show that it had moved ahead of the Soviets. That was the date on which von Braun’s upgraded Saturn I rocket, the two-stage Saturn I SA-5 (an intermediary between Saturn I and Saturn IB), would be launched, putting into orbit the largest payload ever. In a speech made on 21 November 1963 at NASA’s Manned Space Center, Kennedy referred to the day on which the US would fire ‘the world’s biggest rocket, lifting the heaviest payroll into . . .’ He paused, realizing his error, ‘. . . that is, payload.’ He paused again. ‘It will be the heaviest payroll, too.’ The following day Kennedy was assassinated. ‘What a wonderful world it was for a few years . . . with men like you to help realize his dreams for this country,’ Jackie Kennedy wrote to von Braun, in response to his letter of condolence. ‘Please do me one favor – sometimes when you are making an announcement about some spectacular new success – say something about President Kennedy and how he helped to turn the tide – so people won’t forget.’

Group 3 astronauts. Back row: Collins, Cunningham, Eisele, Freeman, Gordon, Schweickart, Scott and Williams. Front row: Aldrin, Anders, Bassett, Bean, Cernan and Chaffee

Meanwhile the Soviets had their own rival to Gemini – Vokshod.

12 October 1964. Vokshod 1. Crew: Vladimir Komarov, Konstantin Feoktistov and Boris Yegorov. Flight time: 1 day, 17 minutes, 3 seconds; 16 orbits.

The flight has been described as the most dangerous of all missions undertaken during the moon race. After pressure from Khrushchev – in order to be seen to be beating the Americans yet again – three cosmonauts were crammed into a craft designed for two. NASA wouldn’t send up a three-man crew for another four years. There was so little room that the crew had to fly without spacesuits, a risk NASA would never have taken. One of the crew, Boris Yegorov, was a doctor. It was another first for the Russians: first to send a civilian passenger into space. Vokshod was designed to bring the cosmonauts back to Earth without the need to eject from the capsule beforehand as the Vostok cosmonauts had had to do. The flight lasted just over a day. During that time, back on Earth, Khrushchev was ousted from office. He was replaced by the dour Leonid Brezhnev, who would prove to be less supportive of the space programme than Khrushchev had been.

Vokshod crew seen after landing.

Pavel Belyayev and Alexey Leonov

8 March 1965. Vokshod 2. Crew: Pavel Belyayev and Alexey Leonov. Flight time: 1 day, 2 hours, 2 minutes, 17 seconds; 17 orbits.

Alexey Leonov won another first for the USSR when he made the first spacewalk, or in NASA-speak the first EVA (Extra-Vehicular Activity) – the collective term for any activity that takes place outside a spacecraft, including a moonwalk. It lasted 12 minutes and nine seconds. He had kept his primitive spacesuit pressurized using elastic bands, but when he tried to get back into the capsule the spacesuit ballooned and he almost didn’t make it. He had to partially deflate his suit, a very dangerous procedure. He lost 12 lbs in body weight trying to get back in his craft. New Nine astronaut Gene Cernan, who would soon have his own problems during an EVA, described Leonov as ‘one of the gutsiest men alive’. And yet afterwards, Leonov said of his spacewalk that, ‘Nothing will ever compare to the exhilaration I felt.’

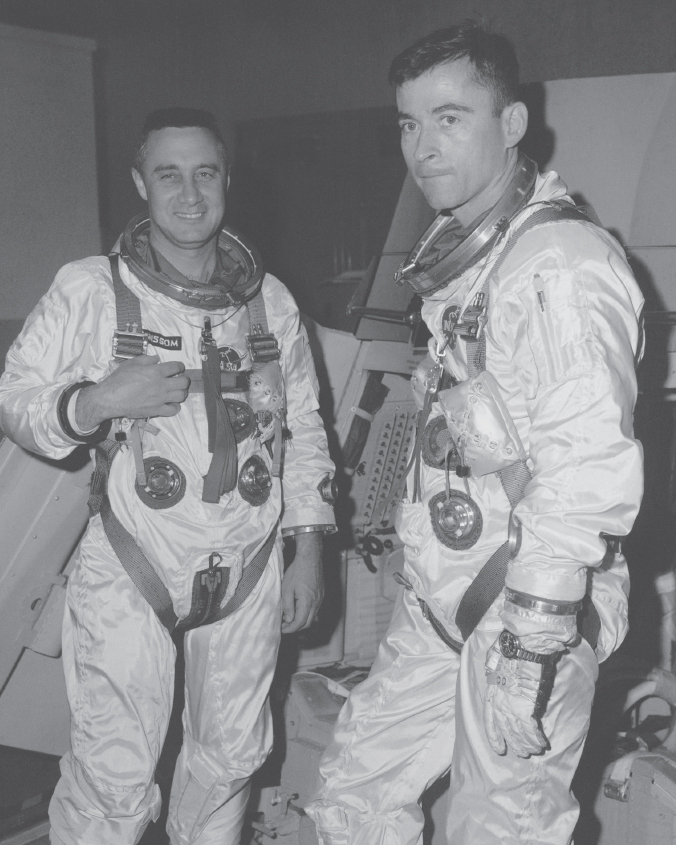

23 March 1965. Gemini 3, the first manned Gemini mission. Capsule: Molly Brown. Crew: Gus Grissom and John Young. Flight time: 4 hours, 52 minutes, 31 seconds; 3 orbits.

Two unmanned Gemini missions had taken place during the previous 12 months. Gemini was the result of the work of over 4,000 contractors from 42 states. The comedian Bill Dana, a favourite of the pilots, joked that every part had been made by the lowest bidder. Gus Grissom, veteran Mercury pilot, said to his wife shortly before the launch, ‘If there’s a serious accident in the space program, it’ll probably be Gemini, and it’ll probably be me.’ Even among the testosterone-fuelled astronauts Grissom stood out. He had to win at everything. He had alarmed his bosses at NASA by being a bit too realistic at a pre-launch press conference: ‘If we die,’ he said, ‘we want people to accept it. We’re in a risky business.’ One of the hardest times for the astronauts’ wives was the period immediately after a launch while they waited for news. They called it the Death Watch. When told that green dye would show the recovery crew where the capsule had splashed down, Wally Schirra’s wife, Josephine, remarked drolly: ‘Is that how we’ll know where to throw the wreath?’

Grissom named his Gemini capsule The Unsinkable Molly Brown, much to NASA’s annoyance. When they insisted he call it something else, he said how about Titanic ? NASA as a whole was not known for its sense of humor. They seem to have settled on an abbreviated Molly Brown. After the first manned mission no other Gemini capsule was given a name.

Gemini 3 was also nicknamed the Gusmobile, because Grissom had had significant input in its design. The astronauts were often involved in the design process, and New Nine astronaut Mike Collins said it was one of the wisest decisions NASA made. The capsule fit Grissom like a glove, but Grissom was only 5 feet 5 inches tall. When NASA realized that 14 out of the 16 astronauts couldn’t fit into it, the design was modified. Collins said that getting into the Gemini capsule was like getting into a Volkswagen Beetle. As it happens, the Volkswagen Beetle was Lindbergh’s favourite car, which he loved precisely because it fit so snugly. He sometimes slept in his car, his legs sticking out the window. He used one of his shoes – he had large feet – as a pillow. The car can now be seen at the Lindbergh museum, in what was once his childhood home.

Gus Grissom and John Young

During the flight, Grissom ate a corned beef sandwich that he had secreted on board. Crumbs might have got into the machinery. Questions were asked in Congress. The medics were up in arms and said it negated all of their tests. But apart from that and some difficulties to do with the escape latch, the flight was a success. In fact it turned out to be more comfortable than had been anticipated. The Gemini simulator used for training on Earth had been torture; no one could bear to stay in it for more than a few hours, but in zero gravity the real experience turned out to be more pleasant.

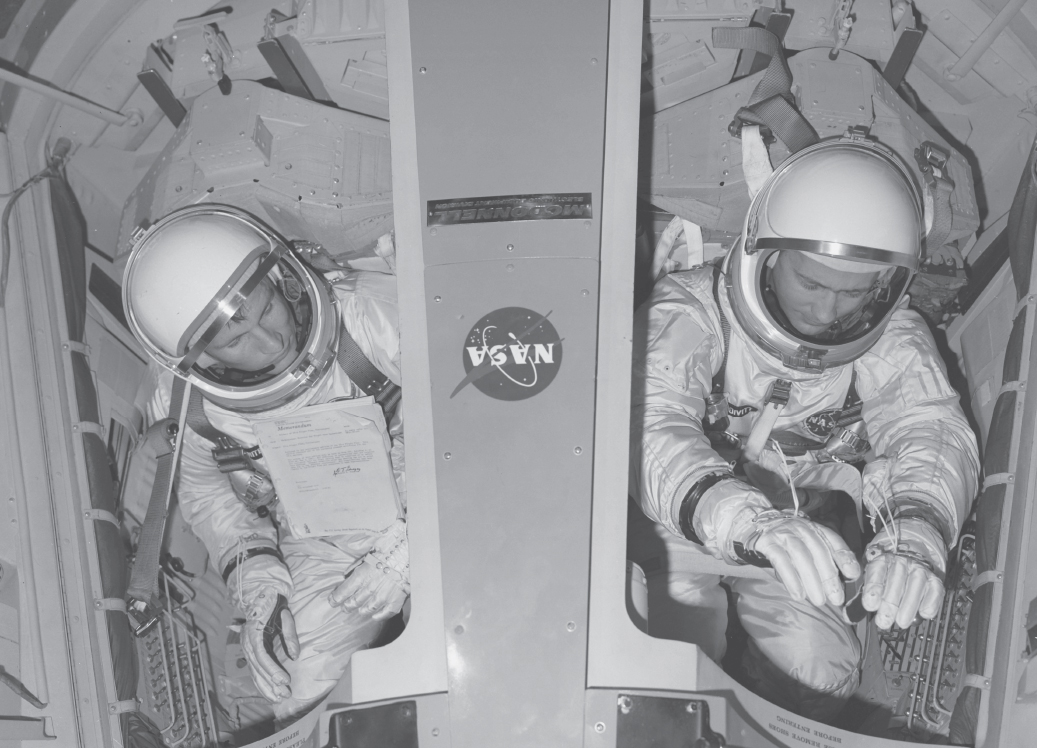

3 June 1965. Gemini IV. Crew: Jim McDivitt and Ed White. Flight time: 4 days, 1 hour, 56 minutes, 12 seconds; 66 orbits. (For some reason the official designation of the flights went into Roman numerals after the first manned mission.)

A first attempt was made at a rendezvous in space. Gemini was sent in pursuit of a ‘pod’ that had, sometime earlier, been ejected away from the vehicle. One of the problems of rendezvous was the counter-intuitive need to move into a lower orbit in order to increase speed. The rendezvous attempt failed.

Back on Earth Jim McDivitt was asked – yet again – to respond to Titov. ‘I did not see God looking into my space cabin window as I did not see God looking into my car’s windshield on Earth,’ McDivitt said, ‘but I could recognize His work in the stars as well as when walking among the flowers in a garden. If you can be with God on Earth you can be with God in space as well.’

Ed White became the first American to walk in space. He was tethered to the capsule and had a camera slung around his neck. Part of his task outside the craft was to take pictures of the craft itself, which had suffered some minor damage. He took 39 photographs, to be assessed back on the ground to see if the cause of the damage could be determined. But he also took the opportunity to turn his camera away from the vehicle and take some photographs of Earth. At that moment he was 135 miles above the Nile Delta. After 20 minutes outside he was told to return. ‘This is great! I don’t want to come back inside,’ he said. He had to be ordered back in. He said he had felt ecstatic during the walk, and that getting back inside the capsule was the saddest moment of his life.

Back on Earth White’s photographs, developed overnight, were spread out on a table, and pored over by a small group of NASA employees. Richard Underwood, unsurprisingly, was immediately drawn to the photographs from the end of the roll that showed the Earth, not those that showed the outside of the spacecraft.

‘Hey, Dick,’ said Gilruth, ‘all the action’s up here.’

‘Well, I don’t think so Dr Gilruth. I think it’s all down here.’

And Gilruth came and looked at the photographs and said, ‘Those are just pictures of the Earth.’

‘Yeah, but we’re looking at things that no human being has ever seen before, parts of Africa and other places.’

There had been several attempts to fire Underwood but Gilruth was now persuaded, and from then on was a supporter of photography as part of the manned space programme, despite continuing opposition from other quarters. On the whole the engineers only wanted technical photographs of clear scientific or engineering value and nothing else. ‘My recollection of those days,’ said Underwood, ‘is a constant battle with my friend Deke Slayton and the other engineers, scientists and astronauts.’ Out of Project Apollo’s multi-billion-dollar budget, Underwood fought to secure an annual budget of initially just $20,000. But Underwood now had an ally at the top, and Webb, too, became a fan. Thereafter Underwood had privileged access to the astronauts to ensure that they learned how to bring back the best possible photographs of the Earth, and later of the moon. White’s were the best photos so far. Underwood said that the photographs that came back from Gemini IV were some of ‘the most spectacular photographs ever to come from the space program’.

Ed White and Jim McDivitt

If he never entirely won over the engineers, Underwood convinced most of the astronauts. ‘Your key to immortality,’ he told them, ‘is in the quality of the photographs and nothing else.’ In the long term no one is going to care about all the data that has come back, those thick black log books will count for very little, what is going to have eternal value is the photographs. After Gemini IV the demand for photographs of the Earth from scientists escalated. Underwood later recalled a visit he had from someone from the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries who happened to be passing the Manned Space Center and had a sudden desire to look at some of the space photographs to see what was in them, particularly photographs of the Gulf of Mexico. He said to Underwood that in five minutes he had learned more about the movement of shrimp than he had in five years on the sea. The specialists were getting the point. And soon so, too, would the public.

21 August 1965. Gemini V. Crew: Gordo Cooper and Pete Con-rad. Flight time: 7 days, 22 hours, 55 minutes, 14 seconds; 120 orbits.

New Nine astronaut Pete Conrad had gone through the earlier Mercury selection procedure and might have made the cut, as his crewmate Gordo Cooper had, had he not rebelled against what in Conrad’s opinion had been an invasive and humiliating admissions procedure. When shown a blank card he handed it back and said, ‘It’s upside down.’ Asked to deliver a stool, he gift-wrapped it and tied a red ribbon around the box. His application was rejected with the note: ‘not suitable for long-duration flight’, which was ironic given that Gemini V would be NASA’s longest flight to date. NASA ended its research into the psychological effects of space flight before Project Mercury was at an end.

Cooper and Conrad inside their Gemini capsule

A second attempt at a rendezvous with a ‘pod’ ejected from the vehicle was made, again without success.

The long flight time meant that the crew had plenty of time to take some ‘magnificent photographs’ to please demanding geoscientists.

25 October 1965. Gemini VI. Crew: Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford. Flight time: 0 secs, and no orbits.

Gemini VI was to be an attempt at a rendezvous between two capsules. An Atlas rocket would first launch an Agena capsule into orbit, and then – launched atop a Titan II rocket – Schirra and Stafford would follow in their Gemini VI capsule. But as the crew was waiting to take off, the unmanned, famously unreliable Atlas rocket blew up six minutes after its launch.

There was a change of plan. Gemini VII would launch next, and a postponed Gemini VI, now designated VI-A, would follow some days later on an abbreviated flight. Instead of chasing an Agena, Gemini VI would now try and meet up with Gemini VII. The two vehicles were not designed to attach to each other but it would be test enough for now if they could be brought close together.

4 December 1965. Gemini VII. Crew: Frank Borman and Jim Lovell. Flight time: 13 days, 18 hours, 35 minutes, 1 second; 206 orbits.

Gemini VII was launched without incident. Gemini VI-A was due to launch nine days after Gemini VII on 13 December 1965. The second attempt to launch Gemini VI was a second failure, almost a disaster. The launch procedure suddenly shut down automatically. Schirra, the Commander, should have pushed the abort button, which would have blown the capsule apart from the booster rocket and parachuted the capsule and crew to safety far away from the launch pad, but Schirra remained cool, suspecting a false alarm. If the booster rocket had been deployed the mission would have to have been cancelled; as it was, it could be rescheduled. The next day an investigation found that a plug had shaken loose. It was also discovered that a plastic dust cover had been accidentally left in a fuel line, which would almost certainly have caused the launch to abort anyway: a reminder, if a reminder were needed, of how much could go wrong, and how tiny the fault could be.

Frank Borman and Jim Lovell back on Earth after almost two weeks in space

16 December 1965. Gemini VI-A. Crew: Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford. Flight time: 1 day, 1 hour, 51 minutes, 24 seconds; 16 orbits.

The third attempt at a launch was successful. Because of the delays, the flight was abbreviated, but there was time enough for Gemini VI-A to get within 5 feet of Gemini VII. Each crew could see the other crew smiling. The first rendezvous had been a success of a kind. A vital operation that would have to be performed if men were to land on the moon had been shown to be possible. The American flights were coming thick and fast. The Russian programme meanwhile was suffering delays, partly due to design problems and partly because of diminished interest from the new Soviet leader.

Early during the Gemini VII flight one of the urine bags burst. Lovell said it was like spending two weeks in a latrine. The question astronauts get asked more than any other is what do they do if they need to urinate or defecate? For everything in space there was a procedure. The Chemical Urine Volume Measure System Operating Procedure was a document comprising 20 instructions: number two is ‘place penis against receiver inlet check valve and roll latex onto penis’ and number 4 is ‘urinate’. The following 16 instructions detail what is to be done with the waste product. In zero gravity, the hardest part was sealing the bag before the contents escaped and started to float around. If any urine escaped the other astronaut would immediately know about it. Gordo Cooper said that during his Gemini flight some urine did escape and all they could do was push the droplets together to make a single ball and keep an eye on it. Astronauts who couldn’t urinate properly in space were called wetbacks. One astronaut said that the best way to defecate in space was not to. But if you had to, there was a blue bag. Basically it stuck to the nether parts. A tube of germicide had to be mixed into whatever had been deposited into the bag. In the confined space of a Gemini capsule any kind of physical activity was almost impossible. Having the other astronaut right next to you ensured that you were only going to go if you absolutely had to, but during a two-week mission such a time would inevitably come. The urine was regularly dumped into space. National Geographic reproduced a colour photograph of urine expelled from Gemini VII. The droplets immediately froze in space and glittered like diamonds. Schirra said it was one of the most amazing sights of the mission. He called it Constellation Urion.

Tom Stafford and Wally Schirra

The last three days of Gemini VII’s almost two-week mission had been practically unbearable. But at least now there was no doubt that the human body could tolerate being in space for long periods without any serious consequences, and long enough certainly to get to the moon and back. Borman and Lovell had been in space for more than twice the length of any of the future Apollo missions.

In the early days of manned flight space was expected to produce a lot of surprises, which was why pilot-engineers had been chosen as the first explorers of space, not scientists: pilots already knew how to react calmly and swiftly to the unexpected. At that time, some scientists had thought that even a few seconds of weightlessness would impair bodily functions, that astronauts might not be able to swallow properly, that nutrients might not get to the stomach or be assimilated. Heart and lungs might get confused. Mike Collins said that when Alan Shepard came back after his 15 minutes in space NASA physicians moved the decimal point. Minutes might be OK but not days in space. After days in space the body’s autonomic system might forget how to work, blood would pool in the lower parts of the body, not reach the brain, astronauts would pass out. Astronauts took a jaundiced view of the contribution made by the medics: ‘The truth of the matter,’ said Collins in his typical dry fashion, ‘is that the space program would be precisely where it is today had medical participation in it been zero, or perhaps it would even have been a little bit ahead.’ In fact weightlessness does cause some problems, but they are not serious. The flapper valves in veins that stop blood falling down into lower extremities give up after a while in space. Prolonged weightlessness can make you feel light-headed when you return, before the flapper valves kick back into action. Bone density reduces and muscles atrophy. Some astronauts built themselves up in preparation, but, perhaps surprisingly, NASA had no formal fitness programme for astronauts. There is a clichéd idea that the astronauts were perfect physical specimens with genius IQs. In fact their average IQ was around the 135 mark, smart but not genius level. They were fit but nothing like the athletes of today. As far as NASA was concerned, Apollo astronauts could do as much or as little exercise as they liked. Neil Armstrong, first man on the moon, did no exercise. He once told a friend: ‘I believe that every human being has a finite number of heartbeats. I don’t intend to waste any of mine running around doing exercises.’ In the USSR, however, training was rigorous. Film footage exists showing cosmonauts in training; leaping off high diving-boards, running bare-chested and in shorts through birch forests.

The Gemini VII crew returned with photographs of the Earth showing rapidly changing tropical weather patterns. The information contained in just four photographs taken from space would have required the cooperation of thousands of weather stations on the ground.

16 March 1966. Gemini VIII. Crew: Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott. Flight time: 10 hours, 41 minutes, 26 seconds; 6 orbits.

The two previous flights had shown, finally, that two craft could be brought close to each other in space; now it was time to show that two craft could dock together in space.

We know how one of the threads of this story will end. Neil Armstrong will become the first human being to walk on the moon. Armstrong had made his first flight with his father in a Tin Goose in 1936. He had a pilot’s license when he was still a schoolboy. He had been selected to take part in the air force’s project MISS (Man in Space Soonest), cancelled in 1958 and replaced by Project Mercury. MISS had relied on the X-15 space plane, one of the air force’s X-series of experimental aircraft used to test out new technologies to their extreme. There were only ever 12 X-15 pilots, just as there would only be 12 astronauts who walked on the moon: Armstrong belonged to both groups. Armstrong was also a consultant on X-20 Dyno-Soar projected, also cancelled after Kennedy had insisted NASA focus on the moon. The X-15 had been the world’s first sub-orbital manned spacecraft. It made its maiden flight on 8 June 1959, launched from a B-52 bomber at an altitude of 8 miles; so high up there is no air to lift the craft by its wings. The plane became, briefly, a rocket. For less than two minutes before cutting out, a rocket engine fired and accelerated the plane to a speed of around 4,000 mph. The pilot was at this point weightless. It glided back into the atmosphere, steadied by jets, where it again behaved like a normal aircraft with normal controls.

In the 1960s the United States Air Force still defined space as anywhere beyond 50 miles above the surface of the Earth. Any air force pilot who reached that altitude qualified for astronaut wings. According to the United States Air Force definition, 13 flights by eight pilots made it into space. Some of the eight were civilian pilots and they were not awarded their wings until 2005, when the qualifying rules were modified. Some flights reached altitudes beyond the Kármán line (100 kms, 61 miles), the international designation of where space begins. In 1963 Joseph A. Walker was the first X-15 pilot to cross this arbitrary barrier. He reached an altitude of 67 miles, and so joined an exclusive group of human beings that then included only a handful of NASA astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts. Armstrong reached an altitude of almost 40 miles in an X-15, travelling at around 4,000 miles an hour. An X-15 flight retains the world speed record for manned powered aircraft, 4,520 mph. Robert Poole in his book Earthrise says that spectacular photos were taken from X-15s during its five-year period of service and that there were no photos like them until the space shuttle. It seems that all the photographs were taken over America, and though some of them had brief news value in America, apparently they went unnoticed by the rest of the world.

Dave Scott and Neil Armstrong

Research on X-planes had begun in 1946 and for a time it looked as if space planes were the obvious, logical step after aircraft, and surely would have been if not for the moon race. The most famous of the series was probably the first, the Bell X-1 in which Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier. Chuck Yeager was made even more famous as the hero of The Right Stuff (1979), Tom Wolfe’s account of how the Mercury Seven fought behind the scenes to be recognized as test pilots in space rather than just some disposable human component. Chuck Yeager was scornful of Project Mercury: ‘Spam in a can,’ he called it. He had reason to be bitter: even though many contemporaries thought he was the best pilot of all of them, he had been excluded from the astronaut programme because he had only had a high school education. Some astronauts agreed that Mercury pilots were no more than human cannonballs: the risks were outside their control, but on Gemini a new kind of piloting skill came into play, about to be tested on Gemini VIII: the ability to dock one craft to another while both are in orbit.

‘The concept of modern air power,’ von Braun wrote, ‘was a product of thousands of second lieutenants who learned to fly and who familiarized themselves with the new ocean of air that was the challenge of their day.’ With Gemini came new challenges: ‘We must get men out there in freely maneuverable craft and we must let them log hour after hour in space. Soon they will become acquainted with their ships and their environment and they will begin to look about, seek new maneuvers, new ideas, and new concepts.’ Von Braun might just as well have been writing about the barnstorming days of early aviation. This was why the astronauts adored him: he understood them; and he was a pilot too, one of their tribe.

Von Braun was less well liked elsewhere in NASA. It must have rankled that apart from the astronauts von Braun was the only other celebrity. He had initially been cut out of Mercury, and Bob Gilruth, the director of the Manned Space Center (MSC), had chosen the air force’s Titan II rockets over von Braun’s Saturn rockets. Von Braun was naturally peeved. ‘Remember now, we’re entering enemy territory,’ was what one of the team from von Braun’s Marshall Center remembered being told when they went on a visit to the MSC. Gilruth was suspicious of von Braun, both because of his past – when drunk Gilruth had been heard to complain of ‘that damned Nazi’ – and for what he perceived as his opportunism. He said to Chris Kraft, who had been director of Mercury and was now putting together what would be known as Mission Control: ‘Von Braun doesn’t care what flag he fights for.’ Von Braun was undoubtedly an opportunist, but the accusation of disloyalty doesn’t hold water. Von Braun’s biographer, Michael Neufeld, argues that ‘any portrayal of [von Braun] as willing to do anything to advance his self-interest or ambition is simply incompatible with the fact that he regarded loyalty as more important than financial gain.’ If anything von Braun could be accused of being too loyal.

Armstrong and Scott were so insulated inside their capsule that they felt nothing when the Atlas-Agena combination was launched barely a mile away. Soon after, their Titan II-Gemini combination took off in pursuit. The launches were a success. Armstrong and Scott in their Gemini capsule, and the Agena vehicle they were required to chase and catch, were both put into orbit. At 185 miles above the surface of the Earth, Armstrong steered Gemini VIII so that it met up with and docked with the Agena vehicle. And then things started to go wrong. As soon as the two vehicles were locked together the new configuration began spinning. Armstrong had no choice but to undock, but then Gemini started to spin even faster. The crew was in danger of losing consciousness, and the craft risked breaking up, but quick thinking and untold hours in a simulator paid off and Armstrong was able to bring Gemini under control just in time. The mission was aborted and an emergency landing procedure kicked into action for the first time in the US space programme. Because the mission was ending unexpectedly, three days early, the capsule landed in the Pacific rather than the Atlantic as had been planned. NASA’s ability to second-guess possible changes of plan came into its own. By the time they splashed down there was already a destroyer waiting to pick them up.

Among the astronauts there was gossip. The men could be surprisingly bitchy. The fault must have been Armstrong’s, some of them implied. NASA’s management, however, was impressed with Armstrong’s ability to remain cool under great pressure. On this, and another occasion to come, Armstrong’s piloting abilities were tested to his considerable limit.

Bitchiness hid an astronaut’s greatest fear: making a mistake in front of colleagues. A few weeks before the Gemini VIII flight, New Nine astronaut Elliot See crashed a NASA jet trainer, T-38, as it came in to land. In the plane with him was Group 3 astronaut Charlie Bassett. They both died. Together they had been the crew assigned to Gemini IX. The weather had been bad but a subsequent investigation headed by Alan Shepard ascribed the fatal accident to pilot error. Deke Slayton had been heard to say that ‘Elliot See flew like an old woman,’ and was particularly angry that See’s poor judgement, as he saw it, had killed Charlie Bassett too. For the astronauts, nothing afterwards was ever as dangerous as the training at their Edwards Air Force Base had been; the chances of being killed were endless. In the 1950s an average of one test pilot died every week. In 1952, 62 pilots died in a nine-month period. Out of the Group 3 intake of 14 astronauts, four died in accidents in T-38 training jets. In addition to Elliot See and Charlie Bassett, Group 3 Theodore Freeman died before he had even been selected for a NASA flight. Fellow Group 3 astronaut Clifton Williams died in 1967, after he had been selected for Gemini X.

NASA protocol dictated that the widows were to be informed of their husbands’ death only by an astronaut, not by friends or neighbours. Many of the astronauts and their families lived close, sometimes next door, to each other, so the first people on the scene were naturally the wives of other astronauts, sent by their husbands but told not to say anything, just to wait until the designated male turned up. NASA was meant to be a civilian operation but many of its customs and practices mimicked those of the military. It was military practice that the widow of an officer who had died in action should move out of the camp as swiftly and anonymously as possible. When Marilyn See turned up at the Manned Spacecraft Center to pick up her husband’s belongings she was barred from entering.

See and Bassett’s flight was reassigned to Tom Stafford and Ed Cernan with a launch date set of 17 May 1966. In his memoir, Cernan describes what had become the typical Gemini boarding experience: ‘We rode the clattering elevator up, watching the shiny metal skin of the tall rocket creep down past us . . . We went through the little door into the White Room, the clean area which was the domain of Guenther Wendt, the Peenemünde refugee who was now chief of the closeout crew. Everyone in there, including our backups, Jim [Lovell] and Buzz [Aldrin], wore long white coats and white caps. They looked like morticians.’ The astronauts called Wendt, who had a thick accent and wore thick glasses, ‘the czar of the launch pad’. It was his task, as it had been during Mercury and would be during Apollo, to perform the last of the closing-out duties.

Cernan’s wife, parents and sister were at that moment at Mass: ‘God was up to date on my plans.’ Cernan had asked if he could wear his religious medallion on the flight. The doctors said no but Deke Slayton overruled them. Once inside the tiny Gemini capsule, perched on the Titan II booster, the crew waited for the launch of the Agena target vehicle. Soon after it was launched the unmanned Atlas-Agena ensemble crashed into the ocean. The launch of Gemini IX was aborted.

3 June 1966. Gemini IX-A. Crew: Tom Stafford and Ed Cernan. Flight time: 3 days, 20 minutes, 50 seconds; 47 orbits.

A second attempt at a launch was successful, but once again there was a problem docking. This time the target vehicle was already rotating when they approached it. The docking attempt was abandoned.

On the last day of the mission, Cernan went on the first long spacewalk. NASA ‘shrinks’ had warned him that he might become disoriented ‘or swamped by euphoria’, as if he were in a headlong fall. ‘Ridiculous,’ he said. He experienced no sense of disorientation, falling, or of euphoria. Other astronauts had reported differently on all counts; have said that for the first moments it was impossible not to think that the Earth is where one will fall to, that at first there was a strong desire to hold on tight as if to a cliff that is itself falling, that only gradually did the realization come that even if you let go there was nowhere to fall to. To be in orbit is to be in a state of perpetually falling. It is what is happening right now to all of us here on Earth, even if we are unaware of it experientially.

Cernan had more to worry about than the risk of euphoria. He was wearing 14 layers of clothing: long johns; a nylon comfort layer; a black neoprene-coated pressure suit; a restraint layer of Dacron and Teflon link net that was like chain mail and intended ‘to maintain the shape of the pressure suit’; seven layers of alu-miniumized mylar ‘with spaces between each layer for thermal protection’; a layer to protect against dust-sized meteors; a white nylon outer layer; and finally heat-resistant leg coveralls. He said you could take a blowtorch to him and he would not have felt it. After his space suit had been pumped up to the prescribed pressure it was so stiff he said it was like wearing ‘a rusty suit of armor’. From the start, the suit ‘took on a life of its own’. Outside the craft in the harsh environment of outer space, the sky was pitch-black but the sun blindingly bright. Inside the pressurized clothing his body was burning up huge amounts of energy carrying out even the simplest task. Weightlessness is all very well if you just want to float around aimlessly, but try to perform the smallest deliberate action and weightlessness becomes a hindrance. The suit’s cooling system struggled to cope, and in the blinding light his facemask soon fogged up. After two hours and seven minutes, his EVA at an end, Cernan expended so much energy squeezing himself back into the capsule that he became exhausted, and his heart rate soared dangerously high. Stafford was so shocked at the colour Cernan had turned that he sprayed him with water, knowingly going against procedure and running the risk of an electrical short.

Tom Stafford and Ed Cernan

Richard Underwood’s informal position within the NASA structure allowed him a degree of freedom that was unique within what was otherwise a strictly hierarchical organization. The astronauts trusted him, and told him that they were too wired to sleep during their designated sleep periods; that they put on a pretence of sleeping to satisfy the control centre, and spent the time ‘Earthgazing’, looking out the windows at views no one had ever seen before. From Gemini IX onwards there was supposedly a photographic timetable for each flight, but Underwood perpetrated a subterfuge that allowed the astronauts some leeway. Inside the adapted Hasselblad used on all Gemini flights, Underwood hid a piece of paper on which he outlined a schedule of surreptitious sleep-time photography, a list of times when the craft would be over some point on the globe of interest to some lobbying geoscientist. Underwood had access to weather satellites, and would give the astronauts a heads up when the conditions were good enough to take a photograph. He called it photography for insomniacs. The astronauts were more than happy to play along; it gave them a rare sense of independence and the opportunity to be more than just a man in a can; to be artists. The flight controllers were sometimes baffled afterwards about when some of the photographs could have been taken. Despite NASA’s attempts to formalize everything, Underwood’s relationship with the crews would remain informal. Not that he couldn’t also be strict. He would shout at any astronaut he thought was doing a bad job.

NASA had come to appreciate the fact that having the crew take their own photographs helped keep the security services at bay – surveillance cameras would have attracted the interest of the CIA. Only Underwood truly understood the value of ‘pictures that recorded it the way the astronauts saw it’.

When Underwood looked at the images that came back from Gemini IX, on some there was what appeared to be a UFO, a huge dark object. He decided to keep quiet about it. It was only a decade later that he worked out that the object was a passing Soviet Proton spacecraft, a very large vehicle. At one moment, over southern Africa, the two craft had come within four miles of each other.

18 July 1966. Gemini X. Crew: John Young and Mike Collins. Flight time: 2 days, 22 hours, 46 minutes, 39 seconds; 43 orbits.

This time the docking was a success and the combined Gemini-Agena craft climbed to a higher orbit, 475 miles above the surface of the Earth, a new record. A significant step on the journey to the moon had been taken. The crew was higher above the Earth than any human had ever been, grazing the edge of the Van Allen belt. Scientists had wondered how large a dose of radiation they might experience. In the event it turned out to be much lower than had been feared.

John Young and Mike Collins

During his 90-minute spacewalk, Collins noted that the stars don’t twinkle in outer space but are steady. The sky was unrelieved blackness, with no shades of blue. All was quiet. He had so many tasks to perform there wasn’t much time to look around, but he did have time to notice the colours out there: ‘subtleties . . . clearly discernible to the supersensitive instrument we call the eye, [that] are unfortunately not captured by the rather crude emulsion of the film’. One of his assigned tasks during the EVA was to photograph not ‘the grandeur of the universe’ or the Earth seen from 475 miles up, but, ‘believe it or not’, a titanium plate about 8 inches square divided into four sections, each a different colour. The photograph was to be used back on Earth as a kind of colour test card. If he wanted to take a few tourist photographs, when he had a moment, that was up to him.

When he tried to get back into the capsule, he radioed through to Young that he had a problem. ‘What’s the matter, babe?’ Young asked. The problem was that his eyes were watering in the sunlight, so much so that he couldn’t see out of his visor, couldn’t easily see where he was going. During the struggle to get back inside he lost his Hasselblad. All that they would have in the way of visual evidence of the mission would be the film from one movie camera: ‘an uninterrupted sequence of black sky’. As Collins ruefully observed, ‘in the second half of the twentieth century, an event must be seen to be believed’.

At 38,000 feet, the first parachute, termed a drogue – or what Collins called ‘the little rascal’ – unfurled; it was only 6 feet across, but it slowed the capsule down enough that at 10,000 feet the main chute – 58 feet across – could then be safely deployed. The capsule swayed crazily from side to side as it headed for splashdown.

A few days after splashdown, Collins submitted his travel expenses: three days at $8 a day.

Collins wrote later that he had felt ‘God-like’ as he stood erect in his ‘sideways chariot, cruising the night sky’. Too bad, he said, that he hadn’t been given longer to let it all sink in. There was so much work to do he was hardly conscious of the Earth below him: ‘Work, work, work! A guy should be told to go out on the end of his string and simply gaze around – what guru gets to meditate for a whole Earth’s worth?’ Did he see God? ‘I didn’t even have time to look for Him,’ he said.

Collins had been frustrated after his Gemini flight by his inability to record in words what he felt about being in space. ‘John Magee would have known how to do it,’ Collins wrote in his memoir. Magee, a Spitfire pilot, died aged just 19 in a mid-air collision over Lincolnshire in 1941. A farmer said that he had seen him push back the canopy, and stand on the plane ready to jump. But the crash had occurred at only 1,400 feet. His parachute never opened. Magee had been born in China, his mother British, his father an American missionary. In 1940 he won a scholarship to Yale but chose instead to join the Canadian Air Force. In his short life he wrote just a handful of poems, the most famous of them ‘High Flight’. Collins’ wife, Pat, had typed out the poem on a small card which she had put into the small bag of personal belongings her husband was permitted to take on the mission – in NASA-speak his PPK (personal preference kit).

John Magee

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth,

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds, —and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of —Wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air. . .

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark or even eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

The first and last lines of ‘High Flight’ were inscribed on Magee’s headstone. ‘All that from the cockpit of a Spitfire,’ said Collins. ‘I cry that he was killed.’

12 September 1966. Gemini XI. Crew: Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon. Flight time: 2 days, 23 hours, 17 minutes, 9 seconds; 44 orbits.

Another successful docking with Agena was accomplished. The crew returned with some spectacular photographs of the Persian Gulf. Somehow, during his second spacewalk, Gordon managed to fall asleep outside the craft. At the same time, inside the craft, Conrad was also asleep.

Dick Gordon and Pete Conrad

11 November 1966. Gemini XII. Crew: Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin. Flight time: 3 days, 22 hours, 34 minutes, 31 seconds; 59 orbits.

With the death of Elliot See and Charlie Bassett, Buzz Aldrin, who had been very close to Bassett, made it onto the last Gemini mission. And if he hadn’t made it onto the Gemini mission, he almost certainly wouldn’t have been included in the first mission to land on the moon.

As they were homing in on the Agena target, the radar failed. There and then, using pencil and paper, Aldrin calculated the correct trajectory. The rendezvous and docking was otherwise a success. The two vehicles remained together for almost two days. Aldrin’s EVA was the most successful of all the Gemini spacewalks, the longest – five hours and 30 minutes – and the most trouble-free. A handrail had been added to the outside of the craft: a simple addition that made all the difference. Aldrin proved that it was possible to work in space for an extended period without ill effects. Cernan, who had almost died during his EVA, thought that Aldrin took too much credit. Aldrin had apparently been disdainful of Cernan’s brute force approach. Cernan said Aldrin went round as if he had solved all the problems himself. At times astronauts sound like badly behaved teenagers. During his EVA Aldrin photographed the star field, retrieved a micrometeorite collector and did other chores. By the end of the Gemini missions, NASA was satisfied that rendezvous, docking and EVA had been fully tested.

The Soviets had planned to make four more manned Vokshod flights but all of them were cancelled. Gemini had been a complete reinvention of Mercury, whereas Vokshod had basically recycled and modified capsules left over from the Vostok programme. Leonid Brezhnev’s relative lack of interest in the space programme in his first months in office, combined with Vokshod’s overextended ambition, had led to its downfall. Sergei Korolev had turned his attention to what would be the Soviets’ own reinvention of their manned spacecraft, Soyuz. The first unmanned Soyuz craft was launched a little under two weeks after the last Gemini mission was over. The Soviets had fallen behind, but the failure of Vokshod had not been the only impediment. Early in 1966 Sergei Korolev had died aged 59, his health compromised after the years he had spent in the Gulag. He had gone in for routine surgery to have a tumour removed from his intestinal tract and bled to death. Eight years after Korolev’s death Oberth wrote in a letter to a TASS correspondent: ‘Unfortunately I do not know the names of the people I respect who have created those powerful rockets and the first spaceship.’ Pre-eminent among them had been Korolev. The Nobel Prize committee had at one time asked Khrushchev if the Chief Designer’s name might be put forward. ‘The creator of the USSR’s new technology was the entire nation,’ Khrushchev replied. Now, finally, after his death, Korolev’s identity was revealed to the Soviet people, and so to the world.

Korolev’s star had begun to fade after the death of Khrushchev, and his giant N1 booster, planned to be even more powerful than von Braun’s Saturn V, was ‘mired in technical and financial difficulties’. In the race between boosters the Soviets were definitely behind. Just six weeks after Korolev’s death, von Braun’s Saturn IB was successfully launched. It could put a payload of 16 tons into Earth orbit compared to the 11 tons of Saturn I. The two-stage rocket was a marriage of the first stage of Saturn I and the third stage of Saturn V. The three-stage Saturn V had been designed to put a payload of 120 tons into orbit, but for now there were problems with the second stage.

Korolev’s successor was his deputy Vasily Mishin. He had neither the charisma nor the influence needed to head a project facing unrealistic deadlines.

Korolev’s Soyuz rocket would not have been able to get men to the moon, but it would prove in future years to be the most frequently used launch vehicle in the world. After the Space Shuttle was abandoned, Soyuz was, and still is, the only route to the International Space Station (ISS). Another of Korolev’s designs, the R-11, would later be known as the SCUD missile.

Korolev had written a column for Pravda, ‘Talks with a Chief Engineer’, under the pseudonym Professor K. Sergeev. In his ‘New Year Cosmic Greeting’ on 1 January 1964 he wrote: ‘I can’t help wanting to exclaim, “So much has been done, so many steps taken!” At the same time I must say, “How little has been achieved so far and how much we still have to bring about!”’ As we continue, haltingly, to take our first steps out into the cosmos, his words may well always be true no matter how far we travel into the infinite universe.

The Soviet space programme had not entirely stalled during 1966. Two weeks after Korolev’s death the Soviets’ Luna 9 soft-landed on the moon, another impressive first. When Johnson had asked von Braun what America might do to beat the Soviets in space, a soft landing on the moon had been one of his suggestions. Yet another historic moment occurred on 3 February when Luna 9 transmitted photographic data from the surface of the moon to the Earth. The panoramic images were intercepted – it is likely that the USSR had intended that they should be – and decoded at Jodrell Bank in England. They were reproduced worldwide. At the beginning of March the Soviets’ Venera 3 crash-landed on Mars, the first spacecraft ever to reach the surface of another planet. At the end of March the Soviet space probe Luna 10 became the first spacecraft to orbit the moon, orbiting 460 times before its batteries died.

America made its first soft landing on the moon at the end of May the same year. Surveyor I took thousands of photographs of the moon’s surface that were then transmitted back to Earth and scrutinized for possible landing sites. It was crucial that whenever a manned lander did approach the moon’s surface NASA had worked out both how to land reliably, and that the chosen landing site was not boulder-strewn or too close to the edge of a crater. Surveyor could have taken colour photographs and it could have taken colour photographs of the Earth, but ‘some guys with three PhDs apiece’ argued against it, Richard Underwood said. They claimed they’d get more technical detail from black-and-white film.

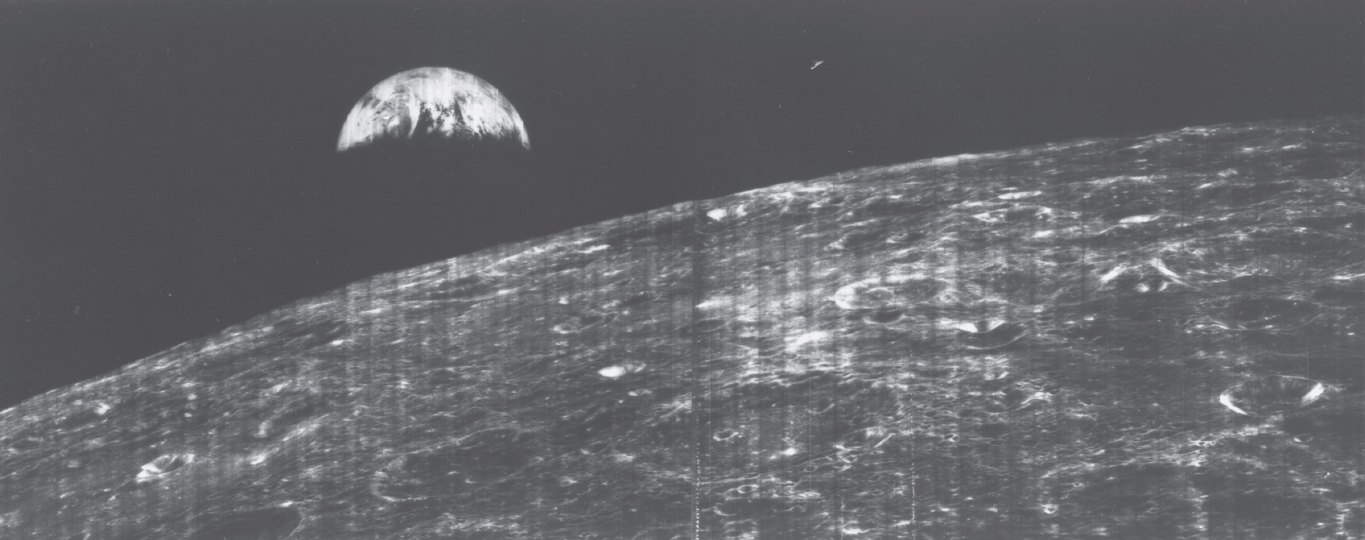

Numerous unmanned missions were undertaken in the next couple of years – a further seven Surveyor craft, and, in addition, programmes like Mariner and Lunar Orbiter – all with the objective of identifying the best place to land a manned craft when the time came. On 10 August 1966 Lunar Orbiter I became the first American spacecraft to orbit the moon. The craft had only enough power to take 211 pictures in medium resolution, but Underwood hoped that at least one of the photographs would show not the moon but the Earth. The photographs would be developed and scanned on board the craft and then transmitted back to Earth in electromagnetic form before being reconstituted, a single photo taking over 20 minutes to transmit. A decision had not been reached even when the craft was in orbit around the moon. There were arguments right up to the last minute, Underwood being told that it was a waste of film, that such a photograph would have no scientific value, and so on. The usual. In the end a senior figure at the meeting, the vice president of Boeing, said, ‘To hell with it. It is a public service. It might be tremendous.’

To take a photo of the Earth, the probe would have to be reoriented and take the Earth photo first, before the moon photos were taken. There was great risk involved, and if it went wrong Boeing – Lunar Orbiter’s manufacturers – would lose its bonus.

Word spread around the centre that the picture had been taken. Senator Joseph Karth, chairman of the congressional committee on space sciences, was soon on the phone to Lee Scherer, NASA’s programme manager: ‘What’s all this about you taking a picture of the Earth?’ Scherer was defensive, and started to reel off any reasons that popped into his head that seemed to justify the taking of the photograph: ‘Well, I don’t give a damn why you did it,’ Karth cut in, ‘but me and 200 million other Americans thank you.’

NASA’s Public Affairs Office led with the Earth photograph, but described it in NASA’s usual technical style: ‘the purpose of the photograph was to obtain data, long of interest to scientists, on the appearance of the Earth’s terminator as viewed from . . .’ Not only is the description terminally boring, it’s not even true that that was the purpose of the photograph. When the photographs from the mission were released those of the moon attracted more attention. Admittedly, without high resolution, and in black and white, the Earth looks just like any other heavenly body, another of the zillions of other spheres whizzing about out there in outer space. As it turned out, repositioning the probe actually improved the photos of the surface of the moon. Seen obliquely there was more detail. Images of nine possible landing sites were identified. Boeing got a 75 per cent bonus. The subsequent official report summarizing all five Orbiter missions did not mention the photograph of the Earth at all. The main significance of the photograph had been missed. Though it was in black and white, and though much of the Earth was in shadow, here for the first time in human history was an image of the whole Earth.

The first photograph of the Earth seen from the moon. Taken by Lunar Orbiter I on 23 August 1966