3 March 1969. Apollo 9. Crew: Jim McDivitt (Commander), Dave Scott (Command Module Pilot), Rusty Schweickart (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of mission: 10 days, 1 hour, 54 seconds. Command Module: Gumdrop. Lunar Module: Spider.

The main goal of the mission was to test the procedures for the docking of the Command and Lunar Modules in Earth orbit before they were performed in lunar orbit during the next mission. When Schweickart developed space sickness, his spacewalk was postponed for fear that he might throw up inside his space helmet and suffocate. Several years later he would describe his EVA as a transcendental experience, but for now he kept quiet, worried that such talk might undermine his chances of another mission.

Photographs of the Earth at close quarters, developed soon after the craft returned home, generated some excitement. Von Braun talked up the practical value of photographs of the Earth. They could be used, he suggested, to locate underground water, reduce disease in crops and forests, find fish, improve maps, detect illegal dumping of toxic waste, locate oil and minerals, measure ice and snow, soil fertility and salinity, and prevent famine.

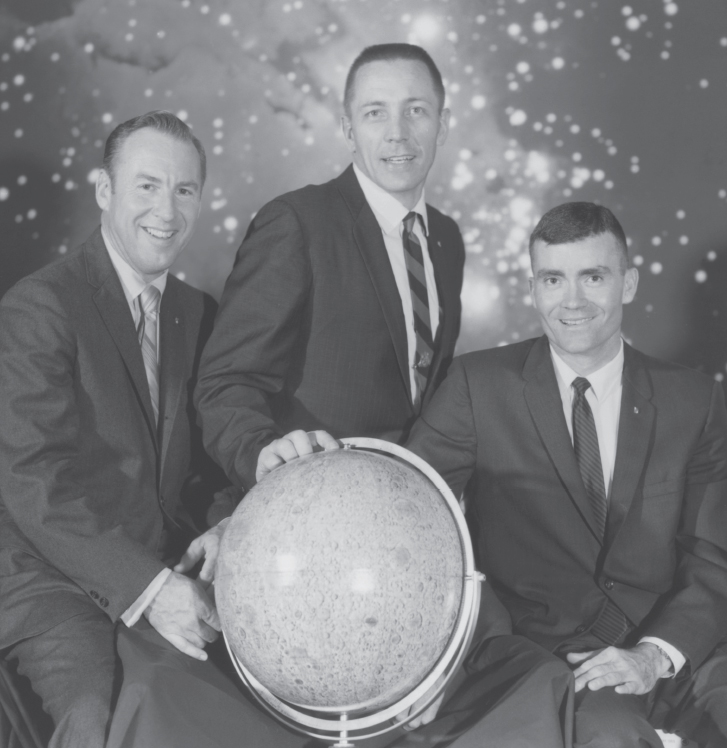

Jim McDivitt, Dave Scott and Rusty Schweickart

Gene Cernan, Tom Stafford and John Young

18 May 1969. Apollo 10. Crew: Tom Stafford (Commander), John Young (Command Module Pilot), Gene Cernan (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of flight: 8 days, 3 minutes, 23 seconds. Command Module: Charlie Brown. Lunar Module: Snoopy.

The main goal of the mission was to attempt to dock the Command Module and Lunar Module in lunar orbit. The crew came within 10 miles of the moon’s surface, even closer than the Apollo 8 crew had. To come so far, and to get so close! The mission returned with some fine photographs of Earthrise, but everyone’s focus was on the upcoming mission.

16 July 1969. Apollo 11. Crew: Neil Armstrong (Commander), Mike Collins (Command Module Pilot), Buzz Aldrin (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of mission: 8 days, 3 hours, 18 minutes, 35 seconds. Command Module: Columbia. Lunar Module: Eagle.

Mike Collins, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin

President Nixon had asked if he might have dinner with the crew of Apollo 11 the night before the launch. Chuck Berry, the NASA doctor, forbade it, saying that the risk of infection was too great, which was odd given that the crew was not living in a germfree environment, and odder still that the privilege had once been granted to the Lindberghs.

The next morning, in the elevator going up the side of the rocket to the White Room, Mike Collins wondered what was amiss, and then realized: there were no people. He was aware that a vast crowd had turned out at Cape Kennedy, but he said he already felt closer to the moon than to them. And yet if, in his mind, he was already on his way, he was also aware of the absurdity of it all: ‘Here I am, a white male, age thirty-eight, height 5 feet 11 inches, weight 165 pounds, salary $17,000 per annum, resident of a Texas suburb, with black spot on my roses, state of mind unsettled, about to be shot off to the moon. Yes, to the moon.’ He had decided that their chances of returning were about evens. Apollo’s engineers were more optimistic: they estimated the astronauts’ chances of being killed at one in 1,000. Everything they did was done with the survival of the astronaut paramount: perhaps the true gift of The Fire.

Once they were in the Command Module there was barely time left to shake hands with pad leader Guenther Wendt.

Collins clambered into the middle couch. Armstrong was on his left, Aldrin on his right. In front and around them were 57 instrument panels and 800 switches. The instruction manual was 330 pages long. The Mercury manual had been a mere 30 pages. Collins felt uncomfortable in his Apollo spacesuit, which was tight around the crotch. He had preferred the Gemini spacesuits, made by a different company. Fortunately it would feel more comfortable in zero gravity.

Among the million or so people who had turned out to watch the launch was Charles Lindbergh. Jim Lovell had been delegated to be his escort. During a conversation in which Lovell extolled the historic importance of what was about to be attempted, Lindbergh stopped him and said, ‘You know, Apollo 8, to me that was the high point of the space program, because it was the first time humans traveled outside the pull of Earth’s gravity . . . You were the pioneers of this. Landing on the moon is just the icing on the cake.’

President Nixon wasn’t at the launch, just in case it all went wrong. Nixon sent ex-President Johnson instead. A speech had been written in the event the astronauts did not return. The funeral service was to be modelled on the service for burial at sea. Johnson was in a foul temper: ‘It was worse than I thought it would be,’ he said afterwards, ‘I hated it.’ Johnson had apparently been in a bad mood ever since he’d lost the party nomination. In the end there had been something tragic about his Presidency. It had begun with ‘a boldness of vision unprecedented since the Roosevelt era’: Medicare, Medicaid and the Voting Rights Act were all part of his legacy, but so was Vietnam. By June 1968 America had committed 535,000 troops. As the war escalated so had Johnson’s passion for space flight dimmed. The war was now costing $3 billion a month. America’s spending was destabilizing the global economy. And still the war would see out another president.

During the launch, Aldrin’s pulse climbed to a modest peak of 88, the lowest pulse rate of any astronaut during takeoff. ‘What’s there to be afraid of?’ he said, ‘When something goes wrong, that’s when you should be afraid.’ On the ground von Braun offered up a short prayer, ‘Thy will be done.’ Lindbergh later said that even from 3 miles away his ‘chest was beaten and the ground shook as though bombs were falling nearby’. The astronauts’ beloved nurse, Dee O’Hara, who probably knew them better than anyone other than their wives, began to cry. Herman Oberth, von Braun’s one-time mentor, was there. He said that the launch was just as he had imagined ‘only more marvelous’. Arthur C. Clarke said that it was the perfect last day of the Old World.

Apart from being thrown around a little, it was much less traumatic an experience than the launch of Gemini had been. Once they were safely underway, the crew could get out of their suits. Not easy. They were like three whales, Collins said, thrashing around in a small tank.

Early in the flight Collins had to perform a difficult manoeuvre. The Lunar Module (LM) had to be released from its protective shroud, reoriented through 180 degrees and brought into alignment with the Command and Service modules (CSM). The LM was housed between the third stage of the Apollo rocket and the CSM in a section called the Spacecraft Lunar Adaptor (SLA), a conical cover that protects the delicate landing module during launch. During the manoeuvre, the CSM and LM were entirely free of each other, hurtling together through space. NASA had wondered if they should be somehow tethered together during the reconfiguration, but realized it wasn’t necessary: the apparent need was psychological rather than physical. Once the three rocket stages have fulfilled their function and fallen away, the four leaves of the SLA detach like petals to expose the Lunar Module. Collins had spent many hours back on Earth practising this manoeuvre in the Apollo simulator. He would have put in eight hours a day if he could have done, but the simulators were always breaking down and the astronauts had had to take it in turns. John Young called the simulator the Great Train Wreck because of its odd shape seen from the outside. Armstrong had been involved in its design. Sometimes the simulations were so complex that the instructors knew there was no way out. They just wanted to see how the astronaut would react. Collins was the only member of crew trained to do the transposition and docking, and the manoeuvres kept him busy during the first hours of the journey. He worried that he had used up more fuel than he needed to, but otherwise the operation went smoothly. Now all he had to do was insert a plug to make an electrical connection between the CSM and LM.

At 28 hours and seven minutes into the voyage, Collins radioed a message to ground control: ‘Houston, Apollo 11 . . . I’ve got the world in my window.’ He said it was a sober, melancholy sight. Armstrong put up his thumb and blocked out the whole Earth. He said it made him feel not big and powerful but small and insignificant.

When they saw the moon for the first time – after a day of being in its shadow – Collins sensed that he and his crewmates were all feeling the same thing: that it was a scary-looking place. But no one said anything. Each mission caught the moon in a slightly differing light. The Apollo 8 crew said they saw the moon in shades of grey between black and white, the Apollo 10 crew that they saw browns too. The Apollo 11 crew saw a new shade: a ‘cheery’ rose colour that darkens through brown into black.

‘You cats take it easy on the lunar surface,’ Collins told his crewmates before he threw the switch that released the Lunar Module. ‘If I hear you huffing and puffing, I’m going to start bitching at you.’

The Lunar Module – ‘nothing more than a taut aluminum balloon, in some places only five-thousandths of an inch thick’, easy enough to puncture with a sharp object – was on its way to the moon’s surface. Building the LM had been one of the greatest challenges of the entire project. It is a clumsy-looking machine, like an insect. Volkswagen later ran a nine-second advertising film campaign: to a background of Sputnik-like space noises, an image of the LM on the moon is followed by VW’s logo. An announcer says, ‘It’s ugly, but it gets you there.’

Collins was left alone to orbit the moon in the Command Module, Columbia – named after Jules Verne’s Columbiad, shot to the moon out of a great cannon. Not that Collins ever felt particularly close to his Apollo 11 colleagues. Amiable strangers, was how he described them. He would like to have been closer, but – even among astronauts – Armstrong and Aldrin were a formidable pair. He liked Armstrong but didn’t know how to get to him, didn’t really know what to make of him. Armstrong kept everything to himself, and Aldrin’s intense gaze was unsettling. He had the feeling that Aldrin was probing him, looking for weaknesses. Aldrin would have made ‘a champion chess player’, he said, ‘always thinking several moves ahead. If you don’t understand what he’s talking about today, you will tomorrow or the next day.’ Armstrong by contrast was very laid back. His application to NASA had arrived a week late. Strings had had to be pulled even to get him an interview. Collins said he had sent in his application before the ink had dried on the form. Neither Aldrin nor Armstrong had any small talk. All they ever wanted to talk about was technical stuff. Both were extraordinary intelligences, both very shy. Aldrin had a tendency not to say anything unless it was absolutely necessary, and then when he did, to be direct, which often got mistaken for rudeness. He might get excited about some small technical detail and talk about it all night long. He was aware that his brain had an exceptional computational talent. His doctoral thesis had been on manned orbital rendezvous, and he was obsessed with talking about trajectories. The astronauts nicknamed him Dr Rendezvous. Why would he not be proud of his abilities? But it was easy to mistake his pride for arrogance. He couldn’t keep to a single subject and was always wondering how everything could be re-engineered or reconfigured in some way. He had the constitution of an ox and could slowly drink a whole bottle of whiskey and be none the worse for it the following day. Yet Aldrin was also emotionally sensitive. His father, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr, was ‘distant and demanding’, and had often been away while Buzz was growing up. Edwin had studied with Robert Goddard and, as an aviation consultant, knew Charles Lindbergh. Whenever Buzz came back from school, the first thing his father wanted to know was how Buzz had done in exams or at sport. If his son had come third, he wanted to know who had come first and second. ‘Third place’, Buzz wrote, ‘doesn’t hold quite the appeal to him that first place does.’ Aldrin Jr graduated in third place from West Point. He flew 66 combat missions in Korea; Armstrong flew 78.

It was ironic, Collins thought, that the most sociable of the three should be the one left to orbit the moon alone. It was ironic, too, that if anything went wrong while they were on the moon – his greatest fear during the entire mission – he would be the one left working out from the Handbook how to take apart and rebuild some piece of technical equipment; he who couldn’t even mend the latch on his screen door.

Collins had been asked countless times before the mission how he would cope being on his own. He said he liked being alone, that that was the essential experience of being a fighter pilot. Now, for 48 minutes every two hours, Collins would be cut off not just from his colleagues but from the entire world. He told his crewmates to keep talking to him, but soon he grew used to the experience and then to really like it: ‘I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three billion plus two over on the other side of the moon, and one plus God knows what on this side. I feel this powerfully – not as fear or loneliness – but as awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation. I like the feeling.’ That ‘almost’ is very Collins.

On a Pan American flight between Honolulu and Manila, Lindbergh wrote to Collins, who received the letter soon after he returned to Earth: ‘Dear Colonel Collins . . . What a fantastic experience it must have been – alone looking down on another celestial body, like a god of space! There is a quality of aloneness that those who have not experienced it cannot know – to be alone and then to return to one’s fellow men once more. You have experienced an aloneness unknown to man before. I believe you will find that it lets you think and sense with greater clarity . . . As for me, in some ways I felt closer to you in orbit than to your fellow astronauts I watched walking on the surface of the moon.’ He told Collins that, though he had observed every minute of the lunar walk, and though certainly it had been ‘of indescribable interest’, it was Collins’ experience that seemed to him to be of ‘greater profundity’. In his Introduction to Collins’ autobiography, Lindbergh was again drawn to Collins’ experience of being alone:

Relatively inactive and unwatched, he had time for contemplation . . . Here was human awareness floating though universal reaches, attached to our earth by such tenuous bonds as radio waves and star sights . . .

Only once before have I felt such extension as when I thought of Astronaut Collins. That was over the Atlantic Ocean on my nonstop flight with The Spirit of St Louis. I had been without sleep for more than two days and two nights, and my awareness seemed to be abandoning my body to expand on stellar scales. There were moments when I seemed so disconnected from the world, my plane, my mind and heart-beat that they were completely unessential to my new existence.

Experiences of that flight combined with those of ensuing life have caused me to value all human accomplishments by their effect on the intangible quality we name ‘awareness’.

The Lunar Module had been difficult to simulate on Earth. The Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, affectionately known as the flying bedstead (a name also given to earlier flying contraptions), was a notoriously tricky machine to handle. Armstrong had to bail out of one during a training flight in May the year before; another test pilot had bailed a few months earlier. Armstrong – like all test pilots, a constantly calculating machine – ejected two-fifths of a second before the vehicle crashed. Bob Gilruth pushed Deke Slayton to stop using it. It wasn’t clear, anyway, how comparable the experience of landing it was to landing an actual Lunar Module in the moon’s weak gravitational field. But Slayton argued that it was better to take the risk now rather than later above the surface of the moon.

After he had bailed and missed death by less than half a second, Armstrong went back to the office. Fellow astronaut Al Bean bumped into a group of astronauts huddled together in a corridor discussing the accident. ‘That’s bullshit!’, Bean said to them, ‘I just came out of the office and Neil’s there at his desk . . . shuffling some papers.’ Armstrong said later, ‘I mean what are you going to do? It’s one of those days when you lose a machine.’

Armstrong had put the odds of a successful landing at 50/50. At 40,000 feet, he turned the LM upside down in order to get a better look at the moon’s surface. They were approaching at 3,000 mph, standing up – seats would have added too much weight – velcroed upright. The landing craft had been pared back, as The Spirit of St Louis had been just over 50 years earlier.

The Lunar Module’s onboard computer had been programmed so that the entire descent could be made automatically, though control of the craft could also be shared or overridden. As the LM got closer to the surface, the computer sent out an error code, 1202. Aldrin didn’t know what it meant. Gene Krantz back at Mission Control didn’t know what it meant either. He recalled seeing something like it before but couldn’t remember when. To make matters worse there were also some radio communication problems. The situation was almost bad enough to justify aborting the landing. There was very little room for error, and only enough fuel for six and a half minutes of flight time.

After some discussion on the ground, Mission Control decided to ignore the error message. The computer was overloaded with information; alarms sounded a further four times as the descent continued. Armstrong had by now taken complete manual control of the landing. There was nothing more Mission Control could do. Slayton whispered to Kranz: ‘I think we’d better be quiet.’

The craft proved to be hard to control manually, and responded sluggishly. The alarms, too, had been a distraction. Armstrong hadn’t had time to look out for the landmarks he had familiarized himself with – poring over lunar maps for hours and hours – back on Earth; and Aldrin now had his attention completely directed towards the instrument panels. Armstrong realized that he had overshot the designated landing site and was flying over an area strewn with boulders. With the gauge indicating that there was only a few seconds worth of fuel to spare, he went in search of a suitable landing area beyond the boulders. His pulse rate rose to 150 beats per minute. As he got closer to what looked like a good spot, dust that had probably not stirred for hundreds of thousands of years blew up from the surface of the moon. And then it was over; the craft settled and came to a standstill, did not disappear into feet of dust as some had feared it might. Later, it was calculated that there had, in fact, been enough fuel to have kept the craft aloft for another 25 seconds. The sloshing fuel had given a false meter reading, as it memorably once had for Lindbergh.

The flying bedstead

The Eagle had landed. Armstrong looked up out of the Lunar Module’s small overhead window. Depending on the position of the sun, sometimes the sky over the moon would be unbelievably rich in stars, at other times, as now, it appeared black and empty. But not entirely empty; there was one brilliant shining object out there, the Earth: ‘It’s big and bright and beautiful,’ Armstrong told Mission Control.

You’d think they’d have flung open the hatch itching to get out and explore, but there were procedures to follow. First, they had to go through a simulation of the next day’s takeoff. They were somehow expected to sleep before the scheduled lunar walk in 10 hours’ time. But even NASA now thought that 10 hours was too long to wait and moved the walk forward four hours.

Of course they could not get to sleep. They said it was the light from the Earth – three times brighter than moonlight – shining into the landing craft that kept them awake.

Buzz Aldrin had known that, if it happened, landing on the moon would be a transcendent moment in human history. He asked Dean Woodruff, the pastor of his local church (the Webster Presbyterian Church in Webster, Texas) if he could think of some way that the significance of the event might be acknowledged. Could he ‘come up with some symbol which meant a little more than what most people might be thinking of’? Woodruff suggested that Aldrin should mark the occasion by taking Holy Communion on the surface of the moon, and wrote to the church’s General Assembly to find out if there were any theological impediments. Word came back that there were not. The bread and wine could be pre-consecrated.

Aldrin told Deke Slayton of his intention and said that he wanted the ceremony to be broadcast to the world. But Slayton, still mindful of Madalyn O’Hair’s campaign and threatened legal action, told Aldrin that he might take Communion if he wished but he would have to keep it to himself. The most that Slayton would allow was the curious concession that Aldrin could recite a prayer on open mike on the way back. After the main event of the moon landing, Slayton thought that by then no one would be paying attention. Clearly the letters that were flooding into the Manned Space Center in support of the Apollo 8 Genesis reading carried less weight then O’Hair’s protest.

Woodruff wrote a sermon, afterwards published as ‘The Myth of Apollo 11: The Effects of the Lunar Landing on the Mythic Dimension of Man’, which he delivered on 20 July, the morning before the lunar landing. He said the event would come to be seen as being more influential than the Copernican or Darwinian revolutions. He wrote that, flying high above its surface, we escaped Earth’s bonds, both the literal bond of gravity and metaphorical bonds. Apollo 11 was a material manifestation, he said, of an ancient myth: that of ‘magical flight’. The myth symbolized humankind’s desire to transcend itself. ‘Perhaps when those pioneers step up on another planet and view the earth from a physically transcendent stance, we can sense its symbolism and feel a new breath of freedom from our current claustrophobia and be awakened once again to the mythic dimension of man.’

At around 5.57pm Houston time, Aldrin prepared to celebrate Communion. He took the pre-consecrated wafers and wine from his personal preference kit, along with a mini flat-packed chalice. Aldrin used a small fold-down table underneath the keyboard of the abort guidance system as an altar. He turned on his mike and made a short statement: ‘This is the LM pilot speaking. I’d just like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever, and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way.’ He was careful not to mention God. Armstrong – who described himself as a deist (though his mother was saddened that he was not more devout) – was unfazed: ‘I had plenty of things to keep busy with. I just let him do his own thing.’

In the moon’s gentle gravity the wine poured slowly out of the flask and curled gracefully against the side of the cup. Aldrin read silently from a small card on which he had printed words from the book of John:

I am the vine and you are the branches

Whoever remains in me and I in him will bear much fruit;

For you do nothing without me.

At home in Nassau Bay, his wife Joan was listening to old Duke Ellington records with only one ear tuned to the squawk box, but she heard her husband’s message and approved. She didn’t know that he was taking Communion at that particular moment but she liked his acknowledgement of a spiritual dimension to the experience of being on the moon beyond the technical. And yet, as Robert Poole acknowledges in Earthrise, ‘It was not exactly an advertisement for the unity of mankind’: one man celebrating Communion alone while another man tried to act as if nothing was happening. Aldrin later said that if he had the chance to do it all over again he would not have celebrated Communion. ‘At the time I could think of no better way to acknowledge the enormity of the Apollo 11 experience than by giving thanks to God.’ It had been meaningful to him, but the astronauts had come, he now said, ‘in the name of all mankind’.

In the event, despite the revised schedule, the moonwalk was delayed. It had originally been planned for 10pm Houston time and then rescheduled for 6pm. Aldrin finally opened the hatch around 8pm.

Aldrin Sr had got involved in what became an embarrassing argument within the Manned Space Center about who should be first out of the Lunar Module. He encouraged Buzz to believe that he should be first on the moon, not Armstrong; and then began to pull strings on his son’s behalf. Buzz appears not to have cared before his father intervened. When it was first announced that he was to be part of the first crew to land on the moon, Aldrin said to his wife that he would have preferred to have been on a later flight: ‘I didn’t want all the press and all the attention for the rest of my life for being on the first landing. Because that’s all the press seems to care about.’ But, seemingly because of the pressure from his father, he came to believe that he had been badly treated when he didn’t get to be the very first man on the moon. Collins thought that Aldrin got so worked up over who should be first out of the Lunar Module that the joy he might otherwise have experienced from walking on the moon was spoiled.

Now, as he attempted to get out of the Lunar Module, Armstrong was forced to his knees in accidental obeisance. He had to crouch and gradually push his way through the door. Once he was outside he pulled a cord to release a TV camera so that the moments to come could be recorded.

The first task to be performed was to throw out the trash. (By the time Project Apollo was at an end, NASA would have put 118 tons of rubbish on the moon: redundant Ranger, Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter probes, spent third stages of Saturn rockets that crashed there, LM descent stages.) Still on the ladder, Armstrong described ‘for the benefit of scientists back on Earth’ the surface of the moon: ‘[It] appears to be very, very fine grained . . . almost like a powder . . .’ Once his feet touched the ground, he uttered the famous words: ‘That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.’ The missing ‘a’ is still argued over. One investigation claims to have uncovered the indefinite article hidden in static. There is something gloriously arbitrary about the statement’s significance, as if everything else that Armstrong and Aldrin said to each other since landing on the moon counted for nothing compared to the first words spoken after human feet – unmediated by the craft, or a ladder, but, nevertheless, still mediated by a spacesuit – had touched the moon’s surface.

The TV footage broadcast from the Command Module had been in colour, at least some of the time. The astronauts considered the onboard camera a nuisance and only worked out how to use it on the way out. Collins talked of ‘camera clap-trap’. He said it was ‘a bloody nuisance of an afterthought’. Armstrong and Aldrin didn’t even know how to turn it on. The only PR training they had had was to be told, glibly, to put on a good show as the world would be watching.

There had been no time to develop a colour camera for use on the surface of the moon. At first, the engineers had not wanted the crew to take a TV camera on board the LM at all, because of the extra weight. Curiously it was the communications director, Ed Fendell, who argued against, saying at a meeting that there was no need to have a live broadcast from the moon. Kraft said, ‘I can’t believe what I’m hearing.’ A row developed. ‘We’ve been looking forward to this flight’, Kraft shouted ‘– not just us, but the American taxpayers and in fact the whole world – since Kennedy put this challenge to us.’ Even dead, Kennedy was still the final arbiter. And now, because they had left the decision so late, the world had to make do with black-and-white TV images of the first moonwalk. It had even been argued that the stills camera that was to be taken onto the moon’s surface should have black-and-white film in it, because – an often repeated argument – black-and-white photographs showed greater detail. Then someone from the press office angrily asked what they thought a black-and-white photograph would look like on the front cover of Life magazine and the matter was closed. By the late 1960s photographs in magazines and newspapers were larger than they had been, and often reproduced in colour. Time magazine went into colour in 1968.

Around 600 million people back on Earth were watching, the largest audience in the history of television up to that time. Depending on which was closest to the spinning Earth, the TV signal was captured by one of three possible stations and relayed from there to Mission Control. From Mission Control the signal was bounced back into space to be picked up by satellite ATS-3, which then relayed the images to the world. We could see men on the moon only because getting them to the moon had brought about a worldwide telecommunications system. Those who saw the landing at the time will appreciate the observation made by Mark Armstrong, aged six. Searching the fuzzy TV images for his father, he said: ‘Why can’t I see him?’

Aldrin followed Armstrong out of the LM, pausing on the top of the steps, not to take in the grandeur of the scene, but to urinate inside his spacesuit. He may not have been first but he could at least mark the territory as his own.

The small planet pleased them. The moon felt almost intimate because of its strongly curved horizon, and there was something lovely, too, about the moon’s light gravitational pull; just enough to give a sense again of up and down, yet light enough to turn the moon into a playground, perhaps not so different from the home planet of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince.

Armstrong and Aldrin had brought a flag with them. Armstrong broke into a sweat as he struggled to push the flagpole into the ground. There was nothing between dust and solid rock.

Aldrin became aware of the paradox that they were both further from the Earth than any other human being and yet also the objects of the world’s close attention. He knew that when he returned, he would be asked what it had been like on the moon. And he knew he would not be able to answer that question any better than he had the question everyone wanted an answer to after Gemini: what had it been like in space? When they saw the TV footage, later, back on Earth, Aldrin turned to Armstrong and said, ‘Neil, we missed the whole thing.’ Collins missed the whole thing too. Just as Armstrong was about to step onto the surface of the moon the link between the Command Module and the LM failed. The link was restored just as Columbia passed into the moon’s dark side.

Before they got back into the LM, Armstrong and Aldrin left behind their boots, and their camera. Any weight that could be saved meant extra fuel. When Armstrong threw his backpack into the Lunar Module, Mission Control picked up the vibration on a seismometer on the moon’s surface. ‘You can’t get away with anything any more, can you?’ Armstrong told them. And he was right. It was the beginning of a new era of continual surveillance. The first moonwalk was over. It lasted barely two and a half hours, and because NASA was worried about how the spacesuits would hold up, they had walked not much more than 65 yards from the LM. Armstrong had been given only 10 minutes in which to collect rock samples.

The ascent engine fired up. The flag fell over. The Lunar Module rose above the moon’s surface, leaving behind the descent engine and the ladder they had used to get down. On the ladder was a plaque – the so-called Goodwill Message from 73 world leaders – that read in part, ‘We Came in Peace for all Mankind,’ along with facsimile signatures from the crew and the President. Nixon had wanted the plaque to read ‘We Came in Peace Under God for all Mankind’, but someone at NASA decided to omit the words Under God. O’Hair’s influence had turned the moon landing into an almost entirely secular event; had turned the focus instead to world peace. No prayers were broadcast from the moon. President Nixon declared 21 July National Day of Participation, calling on every American to pray for the safe return of the crew. Madalyn Murray O’Hair nevertheless protested that among the messages of goodwill was one from the Pope.

The fragile LM quickly accelerated to 57,000 mph. It was much easier to escape the moon’s soft gravitational pull than the Earth’s.

Collins said that the moment he feared most during the whole mission was the possibility that he might have to return alone if anything went wrong with the lunar lander. He said that, afterwards, back on Earth, the moment he always revisited in his imagination was when he first caught sight of the Eagle making its way back to Columbia. It was the best sight of his life, he said. He took a photograph showing the LM, the moon and the Earth together all in a line. All of humanity, all life was in front of him.

Only after the LM had returned did Collins allow himself to think for the first time that perhaps they were going to make it. He wanted to kiss each of them on the forehead but thought better of it. Instead, he shook their hands.

He flipped a switch and what was left of the Eagle was jettisoned with a small bang. Collins was relieved, Armstrong and Aldrin sad to see it go.

Congratulations came in from all over the world. Collins thought they were a little precipitous. Couldn’t they at least have waited until after they had left lunar orbit? Among the messages was one from Esther Goddard. Could Robert Goddard ever really have anticipated this moment, Collins wondered?

The crew made their last broadcast of the mission. Aldrin told the world that ‘in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms came to mind: “When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained; What is man, that thou are mindful of him?”’ Collins wondered afterwards if they had missed an opportunity, wondered whether their messages had been just a little trivial. He tried to imagine what a crew made up of a philosopher, priest and poet might have made of what they had experienced. But he had come to the conclusion that, though his fanciful crew might have expressed themselves better, they might not have made it back – forgetting, perhaps because their minds were on higher things, to push the circuit breaker that enabled the parachutes to open.

Lindbergh turned down Nixon’s invitation to greet the returning astronauts at sea. He said he did not want to be taken back to a ‘life I am most anxious not to re-enter’. He meant, one in which he was the centre of attention.

After splashdown, the reporter Eric Sevareid turned to the CBS News anchorman Walter Cronkite and said, ‘You get a feeling that people think of these men as not just superior men but different creatures. They are like people who have gone into another world and returned, and you sense they bear secrets that we will never entirely know.’

When NASA spread out the photographs that came back from the mission, among them were Earthrise photographs even better than those from Apollo 8, but the public and press would focus all their attention on the landing.

‘Where are the photographs of Neil?’ someone at the meeting asked. Armstrong had taken a fine portrait of Aldrin standing by the flag, but there was nothing like that of Armstrong, the first man on the moon. Underwood said Aldrin hadn’t taken a photo of Armstrong because he was still mad at him for being the first out, but more likely it was because the camera, a Hasselblad of course, was hooked onto Armstrong’s chest, so that he could more easily photograph features of the lunar surface and materials to be collected. It wasn’t easy to take it off and hand it over. Apparently the swap was about to happen, but the President came on the line. Nixon told them, and the world, that it had been ‘the greatest week since the Creation, that for one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people of the earth are truly one . . .’ And so, because of Nixon, there were no photos of Armstrong.

Someone at the meeting suggested that perhaps they could pretend that the photo of Aldrin was of Armstrong. Who would know? It wasn’t as if you could see his face or anything. But Underwood said it wasn’t worth the risk. ‘There’s some nine-year-old kid out there who’s a space groupie, and he knows every aperture and wire and seam in a spacesuit. The day after you publish it, the New York Times is going to get a letter from that nine-year-old kid saying, No, you’re wrong. That’s Buzz Aldrin.’ So nobody mentioned it. Underwood said that this was NASA policy for a lot of things. The only images of Armstrong that came back are of him in the shadows, working. Nobody in the press seemed to notice.

The day after the launch, the New York Times ran an article referring back to the article it had run on 12 January 1920, in which Robert Goddard had been accused of not understanding Newton’s Third law. The New York Times had then ridiculed the idea of propulsive space travel. The article, published on 17 July 1969, ended: ‘The Times regrets the error.’

The President threw an extravagant party for the returning astronauts in Los Angeles. Guests at the Moon Ball included Wernher von Braun, Charles Lindbergh, Eddie Rickenbacker, Mrs Robert Goddard, Howard Hughes, Jackie and Aristotle Onassis, Fred Astaire and Joan Crawford. LBJ and Lady Bird Johnson sent their regrets. There were protesters outside the Moon Ball. One placard – ahead of its time – read: ‘Fuck Mars’. Speaking on behalf of a sizeable minority, Picasso said, ‘It means nothing to me. I have no opinion about it, and I don’t care.’ John Updike later voiced that same malaise in his novel Rabbit Redux: ‘For the twentieth time that day the rocket blasts off, the numbers pouring backwards in tenths of seconds faster than the eye until zero is reached: then the white boiling beneath the tall kettle, the lifting so slow it seems certain to tip, the swift diminishment into a retreating speck, a jiggling star. The men dark along the bar murmur among themselves. They have not been lifted, they are left here.’ The New York Times reported that bars in Harlem had been tuned to a baseball game, not to the lunar landing. ‘The moonshot . . . was imposing,’ the Stockholm Expressen allowed, ‘but it also gives a horrible feeling to think that the USA can handle tremendous technical problems with such ease while it has considerably more difficultly coping with those of a complicated social, political, and human nature.’ The year after the moon landing the poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron released his debut album ‘Small Talk at 125th and Lenox’. The track ‘Whitey on the Moon’ – ‘I can’t pay no doctor’s bills / But Whitey’s on the moon’ – nailed what to some was a major failing of the moon landing: that it had been just another exercise in white supremacy.

Collins could have gone on to command a later mission if he had wanted to, but he decided that this was to be his one shot. He said that after the experience he just couldn’t get excited about anything the way he could before Apollo 11: ‘I seem to be gripped by an earthly ennui which I don’t relish, but which I seem powerless to prevent . . . not many things seem quite as vital to me any more. My threshold of measuring what is important has been raised; it takes a lot more to make me nervous or to make me blow my cool . . . That doesn’t mean I have acquired a complete guru-like detachment. I still get irritated, and I still express irrational annoyance.’ And the question that would make him most annoyed was the one everyone wanted an answer to: ‘If one more fat cigar smoker blows smoke in my face and yells at me, “What was it really like up there?”, I think I may bury my fist in his flabby gut; I have had it with the same question over and over again.’

Flying in space had, however, changed his perspective on himself. It wasn’t obvious to others, he thought. Outwardly he seemed the same. And certainly he hadn’t found God on the moon, but he cared more now about what really mattered to him. He had taken up painting, he wrote poetry:

The moving line skims, sure and swift

Green as a snake across the wall.

A linear lie of circular progress, it tells us nothing,

Except that man must keep his sensors saturated.

Collins wouldn’t be the only astronaut who came back and turned to art.

When he had been a boy undergoing painful dental work, Collins had learned to imagine himself floating up at ceiling height looking down on himself. It was a way, he discovered, of removing himself from the pain. The boy he looked back on in pain was not him, just someone he was looking at. He had done the same thing as a pilot, and had taken his aerial perspective back with him to Earth. Now, when things were not going well on Earth, he would lift his mind out there into space, ‘and look back at a midget Earth’. As a pilot, the remembered view from the clouds was comforting but as an astronaut, the view from the moon’s orbit was ‘even more supportive’.

‘I travelled to the moon,’ Buzz Aldrin said, ‘but the most significant voyage of my life began when I returned.’ He had what he called, ‘a good old American nervous breakdown’. For a time he became depressed and turned to drink. His mother had died of a self-administered drug overdose the year before. Her father had also committed suicide. As a child he had read a story in which travellers to the moon had returned insane. The story had haunted his mission. Aldrin told his wife Joan that he was sick and tired of talking about the moon. How many times can you say it was mystical up there? But his father didn’t let up on him: now that he had been to the moon, the world might be at his feet, if only he would assert himself more.

Aldrin described himself as ‘introverted, supersensitive, a perfectionist, concerned about what people thought of me . . . No wonder I was in trouble.’ He thought he had become a better person for going through his breakdown: ‘I got a chance to redo my life.’ Joan described him as being a ‘curious mixture of magnificent confidence, bordering on conceit, and humility’. She had hoped that after the moonwalk he might become more relaxed and open up. Joan told her husband she hoped their life would get back to normal, but Buzz said: ‘Joan, I’ve been to the moon, and I’m never going to be allowed to live the way I once lived. Neither are you and neither are our kids.’

After the Moon Ball, the astronauts had gone on the ‘Giant Step’ tour of the world: 45 days, visiting heads of state in 23 countries. Aldrin found the experience particularly hard to bear. One night he and Joan both got drunk, and he told her that he and the rest the crew were ‘fakes and fools’ for having allowed themselves ‘to be convinced by some strange concept of duty to be sent through all of these countries for the sake of propaganda, nothing more, nothing less’. He and Joan separated afterwards.

When he was asked if he had any regrets, Aldrin said that he wished had looked out of the window more, Earthgazing.

Whatever happened to Neil Armstrong on the moon he mostly kept to himself. When he returned to Earth, he became even more reclusive than he had been before. He announced that he did not intend to fly again. Two years later he resigned from NASA. His longtime friend Robert Hotz, the editor of Aviation Week, said that he understood why: ‘Hell, you’re in this high-tension world of aerospace. You get out on the farm. You look at the mountains across the valley, which are several million years old and are going to be there through the life of the planet. You understand that you’re a short-term phenomenon, like the mosquitoes that come in the spring and fall. You get a perspective on yourself. You’re getting back to the fundamentals of the planet. Neil feels that way, because we’ve talked about it, and so do I.’ After he returned to Earth, Armstrong and his wife Janet split up.

The chalice Aldrin had taken to the moon found its way back to his church, the Webster Presbyterian Church, Texas, not far from the Johnson Space Center at Houston. Each year on the Sunday closest to the anniversary of the lunar landing it is used to serve Communion wine. Almost any object that had been to the moon and returned to Earth seemed to have had conferred on it some mysterious and invisible quality that made the objects – Bibles and First Covers popular among them – somehow hallowed, or at least collectible. Collins had loaded his personal preference kit with small items: ‘prayers, poems, medallions, coins, flags, envelopes, brooches, tie pins, insignia, cuff links, rings, and even one diaper pin’. Also included were 50 elephants carved from slivers of ivory, housed inside a hollow bean. In the 1990s Armstrong stopped signing autographs when he realized that they were being sold for profit, though of course this has only made his signatures all the rarer, and all the more valuable. In 2005 Armstrong intervened when he discovered that his barber had sold his hair-clippings to a collector for $3,000.

Less than two weeks after Apollo 11 splashed down, Madalyn O’Hair finally served her civil suit. Apparently the last straw had been the prayer Aldrin read publicly on the return journey. The action was directed against Thomas Paine in his role as NASA administrator. She sought a court order preventing him and NASA from allowing any further religious activity in space.

During 1969 NASA received 185,876 letters on the subject of religion in space, mostly in support of the Genesis reading. To each letter NASA sent out a standard reply. Other organizations across America had received an estimated 3 million letters.

14 November 1969. Apollo 12. Crew: Pete Conrad (Commander), Dick Gordon (Command Module Pilot), Al Bean (Lunar Command Pilot). Duration of flight: 10 days, 4 hours, 36 minutes, 24 seconds. Command Module: Yankee Clipper. Lunar Module: Intrepid.

The crowd that turned out to watch the launch of Apollo 12 was a third the size of the crowd that had turned out for the launch of Apollo 11. Kennedy’s goal had been achieved, a man (indeed two men) had been safely returned from the surface of the moon. Perhaps the public wondered what was the point of the missions that came after? Even at the White House interest had waned. A memo written to White House staff noted that at 5.52am Commander Pete Conrad would emerge from the Lunar Module and climb onto the moon’s surface: ‘(You know . . . the same old thing – the Armstrong-Aldrin bit.) (Ho-hum).’

During lift off, lightning struck the rocket twice. Pete Conrad’s pulse rate didn’t alter. At Mission Control there was concern that the lightning might have damaged the parachute mechanism, with potentially disastrous consequences for the crew’s re-entry. Since there was nothing that could be done, Mission Control decided to keep their concern to themselves. Inside the Command Module the computer screen had completely filled up with error messages. Conrad started to laugh. His crewmates joined in and they laughed their way into orbit. Apollo 12 became known as the most joyous of all the Apollo missions. The three astronauts were close friends; had matching gold Corvettes which they drove in convoy, and wore matching gold aviator sunglasses with their matching powder-blue NASA flight suits. Commander Pete Conrad was particularly well liked at the Manned Space Center. No one had a bad word to say of him.

Pete Conrad, Dick Gordon and Al Bean

As they orbited the moon, Al Bean thought it looked absurdly cartoon-like. Even close to it was so clearly spherical. He remembered being scared at the sight of the craters but telling himself he wouldn’t be able to do his job if he was scared so he’d look back inside at the control screens until he had the courage to look outside again, and then he’d get scared again . . .

By this time a colour camera had been developed to use on the moon’s surface, but 42 minutes after he left the Lunar Module to take the first moonwalk, Bean accidentally pointed the camera at the sun and burned out the video feed.

The Apollo 12 crew and their matching gold Corvettes

For Dick Gordon – as it had been for Collins – one of the highlights of the trip was welcoming his crewmates back on board after their return from the moon. Gordon beamed at them, telling them to get back in but not to mess anything up. Bean said that when he saw Gordon’s welcoming smile he was filled with intense love for his crewmates. He had just walked on the moon, but for him the defining moment of the trip was that instant of love.

At a news conference after their return, fellow astronaut Pete Conrad was sitting there thinking how in some ways the whole thing had been curiously disappointing; not that different from the experience in the simulator beforehand, and then, as if tele-pathically, Bean turned to him and said: ‘It’s kind of like the song: Is that all there is?’ He was referring to the uniquely dark and humorous popular song, written by Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, and first performed by Peggy Lee, that had been released in 1969, the year of the moon landing. Each verse recounts one of a series of disappointments seen from the perspective of the song’s narrator: the circus act she saw as a girl; the fire that burned the family house down; her first love affair. She would kill herself if she didn’t suspect that even death will turn out to be yet another disappointment.

For a time Bean was gripped by the ‘earthly ennui’ that Collins had also felt, and yet sometimes he’d just sit in the mall watching people and find the experience surreal and thrilling. Collins had turned to poetry; Bean took up painting. He painted only the moon, obsessively over and over again, mixing moon dust into the pigments. He said the best day of his life was when he figured out a technical detail to do with the use of a particular colour.

Charles Berry, the astronauts’ doctor, said that ‘No one who went into space wasn’t changed by the experience . . . I think some of them really don’t see what happened to them.’ Bean said that ‘everyone who went to the moon came back more like they already were’. Several of the Apollo astronauts would articulate the same idea: that they had not been fundamentally changed by the experience of space so much as become more themselves, but perhaps to become more like yourself is to change. Perhaps it is what we mean by growing up.

Bean wasn’t religious, but he wondered afterwards if the Earth as a whole was what the writers of Genesis had had in mind when they wrote about the Garden of Eden. He said that when we look through our telescopes there is nothing we can find out there so beautiful as the Earth that the Apollo astronauts who went to the moon looked back on. ‘We’ve been given paradise to live in,’ he said: ‘I think about it every day.’

Pete Conrad insisted that for him going to the moon had been no big deal. When he was on the moon, he had felt that he was in the right place at the right time and then when he returned to Earth ‘that just shut the door’ on the experience. He didn’t go out and look at the moon afterwards and reflect on his time there. He said no one believed him, but that it was nevertheless true. Some of his fellow astronauts said that that was just the ‘Right Stuff’ talking: that he was supposed to say something like that. But who can deny him his own experience ? Anyway, like Collins he became tired of talking about it. After a while, when he was asked what it had been like, he’d just say: ‘Super! Really enjoyed it.’

11 April 1970. Apollo 13. Crew: Jim Lovell (Commander), Jack Swigert (Command Module Pilot), Fred Haise (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of flight: 5 days, 22 hours, 54 minutes, 41 seconds. Command Module: Odyssey. Lunar Module: Aquarius.

Earlier in the year the director of NASA, Thomas Paine, cancelled Apollo 20, a flight scheduled a few years into the future. With the costs of the Vietnam War escalating, and dwindling public interest, severe cuts were required of the Apollo programme. Public interest in Apollo had fallen after the first moon landing; it fell even further after the second. There were no plans to broadcast the Apollo 13 mission live. ‘New and unusual events have always excited our curiosity and captured our imagination,’ von Braun once wrote. ‘Our first day at school, first airplane flight – and first love . . . With repetition and the passage of time, however, they lose freshness and become routine even if no less significant.’ Mike Collins said something similar: ‘Part of life’s mystery depends on future possibility, and mystery is an elusive quality which evaporates when sampled too frequently, to be followed by boredom.’ The Apollo missions had in the eyes of the public already become routine, but all that changed when, 56 hours into the flight, the crew heard a loud bang. At first they thought a meteoroid had struck the vehicle. Every moment of the drama that then followed was recorded live on TV. In fact an oxygen canister had exploded in the Service Module. NASA told the astronauts’ wives that there was only a 10 per cent chance of them making it back alive. The combined Command and Service module lost its oxygen supply and its power after just two hours. The Lunar Module would have to be used as a ‘lifeboat’, providing oxygen, power and thrust. That they survived was in part due to the crew’s sangfroid and inventiveness. At one point, guided by Mission Control, they were required to construct an air-filtration system out of cardboard and storage bags, grey tape and socks. The crew’s survival was also a tribute to the trajectory experts at Mission Control – among them Katherine Johnson, the black mathematician who had been so admired by John Glenn during the Mercury days – and to the Houston computer. The moon’s gravity was the only way the craft could be put on a homeward-bound trajectory. It meant that the crew had to complete their journey to the moon, moving further away from the Earth before they could start to make the journey back again. The craft arced the dark side of the moon in a mere 20 minutes, less than half the time it would have taken if, in preparation for landing, they had put themselves into a settled orbit. Haise and Swigert began to take photographs, much to Lovell’s annoyance. ‘Relax, Jim,’ Haise said. ‘You’ve been here before, and we haven’t.’

Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise soon after their return

During the return journey the course had to be altered twice using the LM thruster and a watch for timing.

In the dim lighting the crew would have had the best view of the Earth of any mission.

The President declared the day after their return to be a National Day of Prayer and Thanksgiving, but Commander Jim Lovell said that the mission ‘in reality was a failure. When we got back, there were no accolades or trophies, and we weren’t escorted anywhere by the vice president and other VIPs. NASA just wanted to forget about it and move on.’ ‘The only acknowledgment I received,’ he said, ‘was a handwritten letter from Lindbergh who congratulated me on a successful return.’ NASA at that time seems to have been incapable of recognizing the public’s need for a human dimension. Once the crew was returned safely public apathy in Apollo immediately resurfaced. The Apollo 13 mission only began to acquire its current mythological status after Ron Howard’s film Apollo 13 appeared in 1995.

In the summer of 1970, the US had only narrowly approved the building of a space station. The future Vice President, Senator Walter Mondale, had argued passionately against it: ‘I believe it would be unconscionable to embark on a project of such staggering cost when many of our citizens are malnourished, when our rivers and lakes are polluted, and when our cities and rural areas are dying.’ The vote was won by a slim majority, but the writing was on the wall. A few months later the Apollo programme was curtailed further: Apollo 18 and 19 were cancelled.

During 1970 NASA received a further 901,810 letters specifically about religion or the Genesis reading.

31 January 1971. Apollo 14. Crew: Al Shepard (Commander), Stu Roosa (Command Module Pilot), Ed Mitchell (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of flight: 9 days, 1 minute, 58 seconds. Command Module: Kitty Hawk. Lunar Module: Antares.

The Apollo missions had become about moon rocks and scientific experiments. It was not enough to ignite public interest.

Stu Roosa, Al Shepard and Ed Mitchell

Perhaps the scientific case could have been made, but an internal struggle between engineers and scientists at NASA had not yet played out. The scientific argument hadn’t even been successfully made to the astronauts. Al Shepard had made his disdain for geology apparent. A number of astronauts felt as he did. Mike Collins said that his ‘curiosity about things geologic [was] easily quelled’. He thought that NASA geologists did their best to take the magic out of going to the moon. Other astronauts only affected not to be interested in geology, a Right Stuff front that masked genuine inquisitiveness.

In his seminal account of the moon missions, Andrew Chaikin called Apollo 14 the nadir. As if to rub salt into the wound, Apollo 14 became infamous for its flirtation with pseudo-science.

The day after takeoff, Ed Mitchell carried out an experiment; but not one that had been officially sanctioned, this was a secret experiment NASA knew nothing about. While he was floating in his sleeping bag, Mitchell took out a clipboard on which were written a list of random numbers. Each number was assigned one of the symbols typically used in ESP experiments: a circle, a square, wavy lines, a cross, or a star. He then picked a number and concentrated on it and its associated symbol for a few seconds. He repeated the process several times. Back on Earth test subjects were, at that very same moment, trying to decide what number and symbol Mitchell was conjuring up. Mitchell said that the results were promising and that he was neither encouraged nor chastised when NASA found out. Deke Slayton remarked, ‘Hell, NASA doesn’t know everything.’ Von Braun had shown an interest in Mitchell’s experiments. Mitchell claimed that von Braun had hinted at the possibility of using some of NASA’s resources to pursue the experiments further, but that he’d left NASA before anything came of it.

As they approached the moon Stu Roosa was playing his personal tape: a choir was singing the hymn ‘How Great Thou Art’:

Consider all the works Thy hands have made

I see the stars, I hear the mighty thunder

Thy power throughout the universe displayed

Then sings my soul, my Saviour God to Thee;

How great Thou art, how great Thou art.

Like other Command Module Pilots, Roosa relished his time alone orbiting the moon. The darkness out there was palpable, like some damp substance, eerie but not terrifying. The moon made him feel big. It was the Earth that made him feel small. The moon was a dreamscape. Out of the long, sharp shadows he conjured up fabulous creatures, like a child with a magic lantern. He had an epiphany that everything was about light, that humans are creations of light not darkness. He knew now what it was to be utterly alone, and he knew he could bear it.

On the surface of the moon Al Shepard leaned backwards – a precarious movement in a spacesuit – to look at the Earth. He said he began to cry. He was the only astronaut who ever admitted to crying in space.

Ed Mitchell said that when he walked on the moon he felt immediately as if he had become a native of the moon, as if the landscape that had not changed for millions of years had all that time been waiting for them to arrive. The silence was startling. Without an atmosphere, outer space begins at the moon’s surface. Even meteorites crash there silently. Inside their spacesuits and inside the lunar landing module they had brought sound to the moon. How different being there than on the Earth’s surface, cocooned by the Earth’s atmosphere!

When they were all back on board the Command Module, Kitty Hawk, climbing away from the moon, Ed Mitchell was filled with a profound longing, a kind of homesickness for the moon he was leaving and would never see again, like the sickness of love perhaps, or the troubadours’ longing for their distant lady. ‘It wasn’t merely the view that was so powerful, it was the idea.’ The next day, during the journey back to Earth, he looked at his home planet and something inside him changed, though at the time he was unaware what it was. He had looked at the Earth many times during his trip to the moon, and each time had been mesmerized, but this time was different. It would take him several years to assimilate what had happened to him. Out there, ten times as many stars are visible than from the most propitious vantage point on Earth, and are ten times brighter. ‘There is a sense of being swaddled by the universe,’ Mitchell said. In space the universe seems ‘more intelligent than inanimate’. He was vividly conscious on his return journey both of the separateness of the stars and planetary bodies but simultaneously also was aware that he was ‘an intimate part of the same process’. He said that after such an epiphany nothing could ever be the same again. Back on Earth he felt a strong ‘desire to live life to the fullest, to acquire more knowledge, to abandon the economic treadmill’. Two years later he founded the Institute of Noetic Studies, an organization devoted to the study of consciousness. He became interested in Buddhist and Hindu writings. He met ‘Native American Indians, Kahuna of Hawaii, shamans of South American tribes, and voodoo priests of Haiti,’ many of whom ‘spoke of kind and loving spiritual connections to all life as fundamental to their existence.’

When asked if going to the moon had changed him, Al Shepard grudgingly admitted: ‘I suppose I’m a little nicer than I used to be.’

Stu Roosa had been a smokejumper with the US Forest Service. Among his personal belongings he took to the moon 500 seeds from five different types of tree. About 420 of the seeds proved to be viable back on Earth. Seedlings were planted across America in the mid-1970s. About 50 so-called moon trees have been identified, among them a Loblolly Pine growing at the Lowell Elementary School in Boise, Idaho, a Douglas Fir at the US Veterans Hospital in Rosebury, Oregon, a Redwood in Friendly Plaza, Monterey, California, a Sycamore at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and two Sweetgums at the Forest Service Office in Tell City, Indiana.

Soon after he had returned to Earth, Ed Mitchell and his wife divorced. He said that what she really wanted was to be married to a shoe salesman. Out of the combined intake of Mercury Seven, the New Nine and the Fourteen, only seven couples stayed together. ‘If you think going to the moon is hard, try staying home,’ Gene Cernan’s wife once remarked.

16 July 1971. Apollo 15. Crew: Dave Scott (Commander), Al Worden (Command Module Pilot), Jim Irwin (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of flight: 12 days, 7 hours, 11 minutes, 53 seconds. Command Module: Endeavour. Lunar Module: Falcon.

NASA would describe Apollo 15 as the most successful of its manned missions, but that success did not translate into public interest. In 1969 the Space Task Group had produced a report: the Post-Apollo Space Program, Directions for the Future. There would be a base in lunar orbit by 1976, and a base on the moon itself by 1978. By 1980 there would be a space station orbiting the Earth with 50 personnel on board. A manned mission to Mars would be launched before 1981. Hundreds of humans would be living in space by 1985. It was a vision that von Braun had mapped out 20 years earlier in Collier’s magazine and in his Mars novel. But by 1971 there was no government or public appetite for such grand schemes. With the long-term goals of space now uncertain, the point of the remaining Apollo missions was cast into doubt. Apollo 14 had proven that humans could live and work for extended periods of time on the moon without ill effect, but that was of limited value if there was to be no base there. The success of Apollo 15 was to be primarily geological. What was to prove popular with the public was the first outing on this mission of the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), affectionately known as the Moon Buggy. Again, the concept can be traced back to von Braun in Collier’s. And it was von Braun who had pushed to make the rover a reality, and his operation at Huntsville that had overseen its development.

Dave Scott, Al Worden and Jim Irwin

On the journey out to the moon Jim Irwin said that the Earth shrank ‘from a basketball to a baseball, a golf ball, and finally a marble . . . the most beautiful marble you could imagine’ – though presumably it had been the most beautiful basketball too. When they got to the moon they couldn’t stop looking at its surface. Al Worden commented that, rather than appearing to be a forbidding place, as others have found it to be, to him it simply looked dead. ‘I had journeyed all this way to explore the moon,’ Worden said, ‘and yet I felt I was discovering far more about our home planet, our Earth.’ He said the experience had been mind-altering. Other astronauts had said much the same thing right from the first manned flight. Perhaps they were beginning to say what was expected of them, or were running out of ways of saying the same thing. Perhaps there truly was a common transformative experience, which most of them underwent and which was a struggle to process.

Dave Scott and Jim Irwin’s time spent on the moon was the longest of any Apollo mission, which meant too that Worden as Command Module Pilot was alone for longer than any other Apollo astronaut. For three days he saw stars to the limit of his eyesight, and the Earth repeatedly rise and set over the surface of the moon. After a while he’d been around so many times he said he began to recognize features on the moon. How odd, he thought, that already I’m seeing things that are familiar to me. He imagined life spreading between the stars, ‘timeless, always there, adapting, propagating, spurred by survival’.

Meanwhile, on the surface of the moon, Scott and Irwin saw shades of gold, another hue to add to the litany of moon colours. On their second moonwalk they came upon a rock, lighter coloured than the rest, and sitting on a pedestal as if it had been placed there ‘to be admired’. The rock was almost as old as the primordial crust of the moon. On Earth the rock was labelled 15415, but became popularly known as the Genesis rock. Dating tests indicated that it was 4 billion years old, almost as old as the solar system itself. The Genesis rock was perhaps the single biggest scientific discovery of the Apollo missions. It helped to show how and when the moon, and indeed the Earth, had been formed. The mission also returned with a core sample that displayed 42 identifiable layers. The bottom layer had not been disturbed for half a billion years.

These and other discoveries from the final missions proved that the moon had never been truly volcanic. It had never lived as the Earth lives now. The moon was how the Earth had been, billions of years ago before it had grown an atmosphere. The Earth had first come to volcanic life before it could support biological life in all its variety. Many scientists wanted to believe that the moon had once had a volcanic age, that it had been more Earth-like in its past. But the missions proved once and for all that the moon had only had a brief and desultory volcanic period and had then died. Most volcanoes on Earth are young, around 100,000 years or less. The volcanoes on the moon are small, rare and between 3 and 4 billion years old.

When Irwin first saw the Genesis rock he ‘sensed the beginning of some sort of deep change taking place’ within him. He wanted to hold some kind of service near where they had made the discovery, but Scott put him off. They didn’t have clearance from NASA. But, the day after, Irwin recited a line from Psalm 121 at the foot of the moon’s Apennine Mountains: ‘I will lift mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help,’ a prayer not in desire of anything in particular, he said, but in gratitude for what was. He became the first, and to date only, astronaut publicly to quote from the Bible while on the moon. Irwin had hoped that Madalyn O’Hair would object. Her action against NASA had gone all the way to the Supreme Court, but on 8 March, four months before the Apollo 15 launch, the court ruled that the relevant principle was the astronaut’s own right to free speech. So long as it was clear that the astronauts spoke in a personal capacity, there was no case to answer. O’Hair’s biographer Anne Seaman wondered if the near-disaster of Apollo 13 had influenced the judges. O’Hair said nothing in response to Irwin’s reading. Perhaps by then she realized that the battle was lost, or that there were other more pressing or controversial causes that demanded her attention. O’Hair had always been expert at choosing to attack what would bring her the most publicity. She may simply have become as uninterested in Apollo as much of the rest of the world had.

Worden was as relieved as his fellow Command Module Pilots before him had been to welcome his crewmates back on board. ‘I’d kept our home clean and tidy for them. But now, as I opened the hatches between the spacecraft I saw two grimy faces,’ he later wrote, as if he were a mother welcoming her children back, too long out at play, with a clip around the ears. ‘Their spacesuits were dirty, and I could smell the moon dust in the air. It was a new, peculiar odor to me, dry and gunpowdery. I kept the hatch closed as much as possible . . . hoping the dust would not spread.’ Scott and Irwin had so exhausted themselves during their final moonwalk that their potassium levels had plummeted. By the time they were back in the Command Module, neither of them had slept for 23 hours, and both had developed heart problems. If they had been on Earth they would have been treated as if they were having heart attacks. NASA’s doctor Charles Berry said that, effectively, in their 100 per cent oxygen environment they were already in an intensive care unit and receiving the best possible treatment; even better for their hearts, they were in zero gravity.

On the way home, Worden made the first deep-space EVA of the Apollo mission. There would be only two others. He had a unique viewpoint, the first person in history to see the entire Earth when he turned his head one way and the entire moon when he looked the other way. The moon was still close enough that he could see its craters clearly, and the frozen patterns of ancient lava flows. And then in the other direction there was the dynamic, vibrant Earth. National Geographic magazine had complained that the number of photographs coming back from the Apollo missions was falling off. There was also an increasing demand for photographs from scientists. After a lot of petitioning from Underwood’s department a camera had been attached to the outside of the craft. Part of Worden’s task during his EVA was to retrieve the camera and film from outside. The camera had jammed. The mission returned with just a few fuzzy photographs. Worden had wanted to take a camera out on his spacewalk with him, but NASA had ruled against it, saying that he’d be too busy. At one point Irwin poked his head out of the capsule to make sure everything was OK. When Worden turned to look at him he saw himself reflected in Irwin’s helmet, and behind Irwin a moon as large as the craft itself. It could have been the most famous photo of the space programme, Worden said.

As the capsule approached the Atlantic only two of the three main parachutes opened, and one of those looked as if it might fail at any moment. It was a hard landing.

Worden said the weightlessness of space was like a homecoming. It felt so natural: ‘As if I had been that way before or belonged in space.’ When they were back on Earth, for a while they were not able to walk easily. They would push at objects, expecting them to move effortlessly away as they would have done in outer space. Nurse Dee O’Hara said that she often witnessed the astronauts’ frustration, in their first days back, at the Earth’s limitations: ‘They have something, a sort of wild look, I would say, as if they had fallen in love with a mystery up there, sort of as if they haven’t gotten their feet back on the ground, as if they regret have coming back to us . . . a rage at having to come back to Earth.’

During the two-week debriefing period that followed their return, Apollo 15 astronaut Al Worden started jotting down impressions of the trip in his hotel room. He said the words seemed to be coming from somewhere else. Most of what he wrote wasn’t even complete sentences. He organized the fragments and published them as a collection of poetry.

A spacewalk

Is like

Being let out

At night

For a swim

By Moby Dick

Worden said his poems were ‘about as good as you might expect from a pilot’, but perhaps the real value of the art being produced by returning astronauts was that it was being made at all. Worden felt that at 39 years old he had been reborn. He said, as a number of the Apollo astronauts had, that he had a new perspective on every aspect of life.

In the recovery ship, the day after he had returned to Earth, Irwin knew ‘his soul had been stirred. He was a nuts-and-bolts man who had come back to something he had never anticipated: the seed of spiritual awakening.’ As Al Bean had, he began to take delight in the simplest activities. Even to sit in a chair was a vivid experience. Two months later he was baptized at Nassau Bay Baptist Church, and soon after that founded a Baptist ministry called High Flight, the title of the pilot John Magee’s poem. He became a powerful speaker. He said that when he was walking on the moon he had felt the power of God as he had never felt it before, and when they had first come upon the Genesis rock, he heard the voice of God speaking to him. He said it had been a literal revelation. After he had read the Psalm at the foot of the moon’s Apennine mountains, his love of mountains deepened. In 1973 he went to Mount Ararat in search of the remains of Noah’s Ark.

Irwin was the first of the 12 moonwalkers to die, of a heart attack aged 61. Whether or not the heart attack was a result of the stress of the long moonwalks is not known for certain.

16 April 1972. Apollo 16. Crew: John Young (Commander), Ken Mattingley (Command Module Pilot), Charlie Duke (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of mission: 11 days, 1 hour, 51 minutes, 5 seconds. Command Module: Casper. Lunar Module: Orion.

As the appetite for a long-term future in space dwindled, so did the scope of the last missions feel diminished. The main purpose of Apollo 16 was to collect even older rocks than had been collected on the previous mission.

Ken Mattingley, John Young and Charlie Duke

Before the launch, Charlie Duke had a dream that was so vivid he said it was one of the most real experiences of his life. He dreamed that he and Young were on the moon and spotted rover tracks. They followed the tracks and saw another rover in front of them with two astronauts aboard who looked just like they did, except that it was suddenly clear to him that the astronauts in front of them had been there for thousands of years.

On the return journey Ken Mattingley went on a spacewalk to retrieve film canisters from the camera fixed to the outside of the craft. This time the camera had operated as it should. Mattingley said that his EVA training had prepared him for everything except for the experience itself. He looked around him and saw the moon in one direction and a crescent-shaped Earth in the other, and yet what he was most aware of was the feeling that everywhere else he looked there was nothing at all.

Charlie Duke went on to become a Brigadier General in the US Air Force, and active in prison missionary work. He said that though he had walked on the moon, his walk with God would last forever. His wife, Dotty, once got into an argument about Ed Mitchell’s experience in space: ‘But it’s not the same God,’ she said.

Looking at ‘the cobalt Earth immersed in infinite blackness’, Gene Cernan wondered if ‘science had met its match’.

John Young was one of only three Apollo astronauts – the other two were Jim Lovell and Gene Cernan – who went to the moon twice. Back on Earth, Young had come to the same conclusion that several other Apollo astronauts had already reached. ‘We worry about the wrong things,’ he said, ‘like the price of a gallon of gas, rather than the Earth as a whole.’

7 December 1972. Apollo 17. Crew: Gene Cernan (Commander), Ron Evans (Command Module Pilot), Jack Schmitt (Lunar Module Pilot). Duration of mission: 12 days, 13 hours, 51 minutes, 59 seconds. Command Module: America. Lunar Module: Challenger.

The last Apollo mission was the first launch to take place at night. In 1963, Valentina Tereshkova had felt the urge to bow to her rocket; now, less than 10 years later, Apollo 17 – bathed in the light of 74 xenon spotlights – also seemed to demand some form of obeisance. The astronomer and writer Carl Sagan said the launch was like a religious experience, as did the social philosopher William Irwin Thompson, who was also at the launch, and who compared the takeoff to the elevation of the Host.