Judith MacKenzie

Harnessing the Power of the Wind

Judith says that most of her good ideas come to her when she is walking. Here she is on the beach in Forks, which, she explains, is as far west as anyone can go before heading east. (If one were to get in a boat and sail on, the next stop would be Japan.) She calls this spot the end of the earth, then points out that the Makah, an indigenous tribe that has inhabited this landscape for thousands of years, describe it as the beginning of the world.

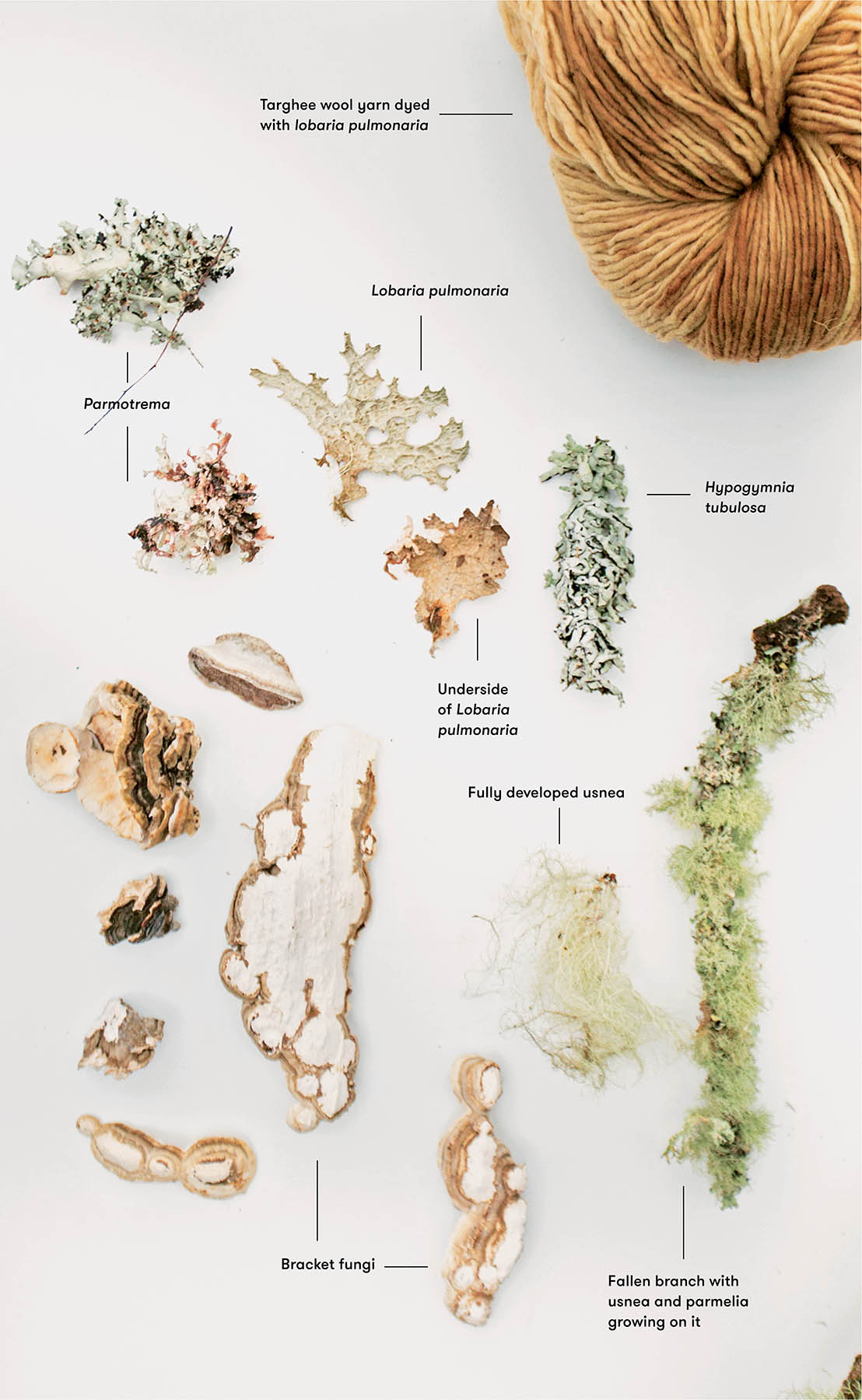

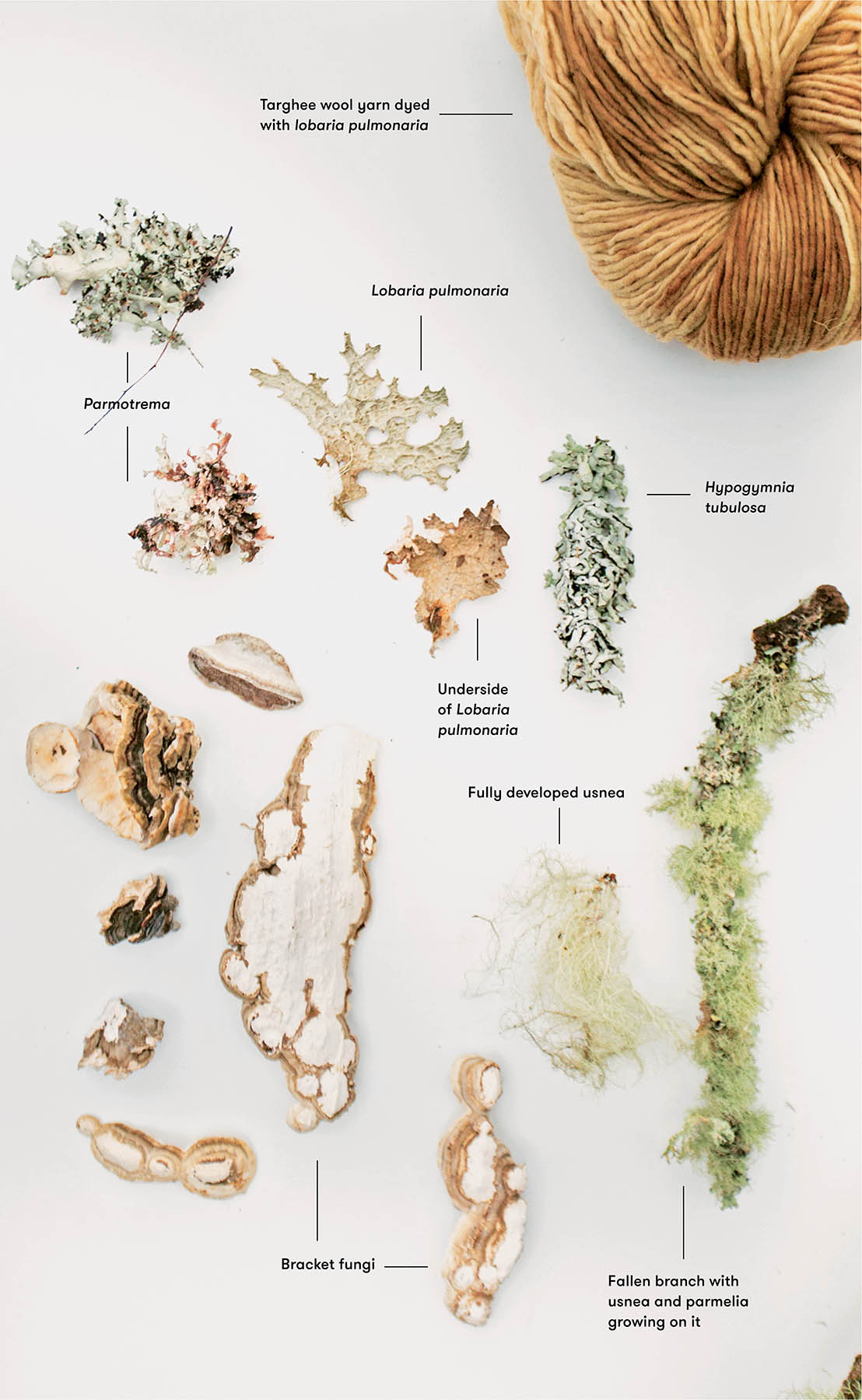

When I was saying good-bye to Nikki McClure and Jay T Scott in Olympia, Washington, and heading northeast to Forks to meet Judith MacKenzie, they suggested a couple of places I might enjoy checking out along the way. It was rainy and chilly, and I wanted to get to Forks before nightfall, but I did manage to break up the three-hour drive with a short hike in the Quinault Valley in Olympic National Park. From there, I posted a photo on Instagram of what I described as “Cousin Itt–style moss or maybe lichen,” a hairy vine that hung from massive tree branches in thick, cobwebby strands. I showed the photo to Judith soon after I arrived, while she was preparing our dinner, and she identified it immediately: It was a lichen called usnea that can be used as a dye—it creates a mustardy yellow color—and also medicinally for inflammation. Judith took a break from chopping vegetables and pulled a glass plate holding dried usnea, lungwort, parmelia, and a few other local lichens from the opposite end of the wooden table we were standing at. Not only did she have the answer to my question, she also had specimens she had foraged to illustrate her point, plus an eight-hundred-plus-page book on the subject called Lichens of North America. Judith, it turns out, has been dyeing with lichens since childhood and, as a teen, studied them while working at Garibaldi Provincial Park in British Columbia, among some of the greatest botanists of that time.

By removing all the non–load-bearing walls inside a double-wide trailer, Judith has given her home the look of an open-plan ranch house meets textile laboratory. At the far end of the kitchen, opposite the front entry, is a portable stainless-steel catering table, fitted with three vats and a countertop work space, which she uses for immersion dyeing. At the far end of the living room is the woodstove she relies on for heat. Near the sliding door at the back porch are a loom and her electric carder.

A crone, in prehistoric matriarchal societies, was a wise, powerful, mature, and respected woman—a healer and wayshower. That is how I think of Judith, one of the most knowledgeable and revered contemporary teachers of spinning, weaving, and dyeing, practices that date back millennia. “Spinning thread,” Judith tells me in her soft, confident voice that seems made for telling bedtime stories, “is what got us out of the cave. Without thread, we would have starved because we couldn’t trap or pull things.” The sails on Christopher Columbus’s ship were hand-spun and handwoven, as were Elizabeth I’s dresses, and all the amazing silver and gold threads, silk brocades, and pile carpets of the Ottoman Empire. Humans have probably been spinning for over twenty thousand years, and weaving for nearly as long. Threads have been made by machine only since the late 1700s.

Judith spun for the first time as a child growing up in Squamish, British Columbia, in the 1950s. At the time, the mountain-ringed town, at the head of Howe Sound and midway between Whistler and Vancouver, was a remote outpost accessible only by a once-a-week boat. Each evening, after washing and putting away the dinner dishes, eight-year-old Judith would grab an empty jug and head down to a neighbor’s homestead to collect fresh milk.

Vintage and antique knitting needles are among the many interesting textile tools Judith has collected over the years.

“Mrs. Axen wore handwoven dresses and beautiful shawls,” Judith vividly recalls. “She had baskets she made herself, and she would sell hand-spun and hand-knitted socks and honey from the bees she raised to the fishermen. I was smitten. I have no idea why. That’s the magic of it all. When I would go down and get milk, I’d stare at the spinning wheel. She finally asked me if I wanted to try to spin. I can’t tell you how happy that made me.” From then on, young Judith would spend as many evenings as she could with Mrs. Axen, a Norwegian intellectual who had left politically unstable Europe with her husband in the 1920s in order to, as Judith remembers, “find someplace on the edge of the world to raise their kids in peace.”

Judith learned to knit from her mother, a socialite turned wild child who left her family to pursue a career as a singer and then married Judith’s father, a labor organizer, but Judith didn’t take to knitting in the same way. Then, as now, she favored creating the yarn over stitching it into garments. Weaving entered Judith’s life many years later, when she was living in a communal home in Vancouver, a single mother of two children, and began taking classes at the nearby Handcraft House and at the University of British Columbia. Among her teachers was the internationally acclaimed artist Joanna Staniszkis, whose exploration of new techniques and unconventional materials resonated with Judith.

“When I first learned to weave, I couldn’t sleep,” Judith recalls. “It was like being on fire. I would dream about it and wake up threading a loom or treadling. It is a physical motion that is like dancing. You move your feet and your hands in different rhythms. It was magical to see cloth grow. I never got over it. I am still not over it.”

Standing with her on the timber-strewn beach, watching the waves rumble, crash, and retreat before our eyes (see photo), and then returning to her house and seeing her splitting wood out back so she can heat her home, I can imagine Judith living a long time ago, at a time when hand-spinning and hand-weaving as well as dyeing with lichens were commonplace and necessary, before machinery took over and was deemed “better.” Judith counters: “When we lose our ability to make things with our hands, we lose part of our humanness.”

From that point on, Judith was determined to make a living doing what she loved. In the 1970s, she mainly sold her weavings and hand-spun yarn. Then, late in that decade, she hit upon a new trend, spinning an unusual, multicolored and -textured yarn that was the diametric opposite of the conventional, solid-colored single- and two-ply yarns that were common at the time. Today it would be called art or novelty yarn, but back then, Judith dubbed it wolf yarn because “it kept the wolf from the door”—that is, it paid the bills. In fact, in its heyday, Judith employed ten people to meet demand for the yarn and garments made from it. By the time that market dried up in the 1990s (when the trend switched back to fine, smooth yarns), Judith had established a name for herself as a teacher and as a judge at fiber festivals, as a custom dyer of exotic fibers, and as a designer of machine-spun yarns that she would have produced at small mills and wholesale to yarn stores. The most successful of her own yarns was a lace-weight bison yarn she sold under the name Buffalo Gals.

Between 1995 and 2009, Judith split her time between a ranch in Montana and teaching on the road, writing articles for textile magazines and authoring a few how-to-spin books along the way. In Montana, she and her second husband ran a sheep-shearing business that took them around the state and into Wyoming and Oregon. Her husband and his team would shear more than a thousand sheep a day, and Judith would class all the fleeces (evaluate their quality based on cleanliness, length, strength, color, and consistency to determine their value at market) before packing them.

Judith points out the usnea growing on the branches of a wild apple tree in her yard.

“In an unspoken way, my grandmother taught me that plants had secrets that some people knew and others ignored, that we had abandoned skills that had worked well for thousands of years but had been forgotten.”

In 2009, after Judith and her husband decided to divorce, Judith moved to Forks, where she had been teaching classes for many years and where she has resided ever since. A small town on the westernmost edge of the United States, five hours from the closest airport, might not seem like an obvious choice for a woman who is on the road teaching about two weeks out of every month, but for Judith, it works. “I understand this landscape,” she says. The ocean is less than two miles from her doorstep, and the glaciated peaks of the Olympics surround her. To incentivize her to move to the town, the City of Forks gave her a large studio in a historic building plus artist-in-residence status. Judith bought 6 acres and a double-wide trailer on a 720-acre property that served as a US military base for a short time in the 1940s and is now inhabited by only fifteen other households. “People who want to be alone live here,” Judith points out. “It’s peaceful and quiet. I hear the ocean waves instead of the freeway, and I see deer and elk, plus hawks, ravens, peregrines, and blue jays right out my window.”

While Judith’s journey has taken many twists and turns (including her Forks studio burning to the ground in 2012; she has since found a space in Port Townsend that she uses for teaching), when I visit her and we talk late into the night, I understand that fortitude, curiosity, and optimism are among the keys to her good life. “It’s an amazing thing to love what you do and to also be good at it,” she tells me.

Her passion for textiles and, in particular, the lichen dyeing we talked about upon my arrival harkens back, she believes, to her ancestors who immigrated to North America from Inverness and the Isle of Skye in Scotland. When Judith was a child, her grandmother regaled her with tales of Scottish fairies who crept into cottages at night and dyed and wove and did chores for the families, and she took her on long walks through the back streets of Vancouver to forage for herbs, fruits, and armloads of flowers that grew out into the alleys. “I learned to love plants—wild and cultivated—from her,” Judith explains. “In an unspoken way, my grandmother taught me that plants had secrets that some people knew and others ignored, that we had abandoned skills that had worked well for thousands of years but had been forgotten.”

After many years of research and experimentation, Judith figured out how to permanently color wool with lichens and fungi. She collects and dries fallen tree branches, removes the lichens and fungi from the wood, then leaves them to age (increasing their color-producing properties). The pieces shown here will produce golds, rusts, coppers, and brown unless they are fermented, in which case some will yield reds and purples.

It is skills at risk of abandonment that Judith has made a career of teaching. “When we lose our ability to make things with our hands, we lose part of our humanness,” she laments. Her students, she believes, attend her classes because they are seeking competence, community, and creative expression, ideals that may not be adequately met in their everyday lives. Suzanne Pedersen, the creator of the celebrated Madrona Fiber Arts retreat in Tacoma, Washington, first met Judith in weaving class in 1994 and taught classes with her for the next twenty-five years. Of her dear friend, she says, “Judith teaches like no one else. She creates a community of learning in every class and demystifies every fiber and process, then brings them alive with history and backstory.”

For Judith, of course, making with her hands is the most natural way of being. As she sits at her wheel treadling with her feet, her fingers gently easing twist into the fiber, transforming a puff of wool into durable thread, she elaborates: “We are drawn to transforming; it is one of our most defining acts. Whether a potter with clay, a weaver with thread, a musician with sound, or a writer with words, we take raw materials and create new forms. It’s as natural to us as a tulip bulb making a tulip. I can take this fiber and, with will and intent, I can spin it forty different ways. It is up to me to decide what it’s going to do and shape it accordingly. Before your eyes, I can take something that is formless and not able to be used in any true way and make it into a sail that you could sail across the Atlantic with. To be able to harness the power of the wind to move you across water, that’s pretty amazing.”

Judith uses a tabletop electric carder of her own design (made with a lathe motor, spare bicycle parts, a carding cloth, and wood) to create multicolored batts that she sells to spinners. Because she layers the fiber onto the carder with great care—“It’s fun, like painting,” she says—the many colors remain distinct rather than merging and muddying. Spinning with it is full of surprises as the colors and textures shift.

A sampling of Judith’s handspun and naturally dyed yarns. Clockwise from top left: lichen-dyed fawn brown wool overdyed in an indigo exhaust bath; natural white mohair dyed with cochineal; natural white wool dyed with archiled rock tripe; natural gray wool dyed with walnut hulls; and natural white wool dyed with walnut hulls.

Judith has been spinning since childhood. “I can spin the fiber thin so I can sew with it or thicker so I can weave with it; I can put a slub in it if I want—that’s my choice,” Judith says as she demonstrates at her wheel in front of a kitchen window.

An assortment of Judith’s treasured handmade tools, including a pre-Columbian beater (center), which she—like the generations of weavers who possessed it before her—uses to push weft threads into place on her loom. As humans, we are, by definition, tool makers, Judith points out. Our brains and our hands allow us to make tools and, in turn, the way we use those tools changes our brains.

A display of some of the unusual fibers with which Judith likes to spin. “When I’m working with them, I feel like I’m reaching my fingers back in time to understand what people made yarn with in the past,” she explains.

“Hello, Melanie. Hope I’m not too late to fit into your schedule. Had an offer to look at some muskoxen I just couldn’t refuse. What you are writing about is meaningful to me. In many ways, my life has been a gamble that being an artisan, working with my hands, could provide a model for a successful life. I have found it a very capable way to make a living, and now that I am well past the spring chicken stage and perhaps quite a bit further into the winter chicken part, I do feel sometimes a little bit scared (what will I do when I can’t feel the fibers move through my fingers well enough?) and a little bit smug (that I have been able to have such a life). But mostly I just feel more than a little bit on fire to see what will happen next in my work.”

—An email from Judith, after I wrote to her about planning a visit