Members of the guild gathered in Marion Coleman’s living room to share with me their stories about the role that quilting and the guild play in their lives. Afterward, we had a show-and-tell and lunch.

African American Quilt Guild of Oakland

Members of the guild gathered in Marion Coleman’s living room to share with me their stories about the role that quilting and the guild play in their lives. Afterward, we had a show-and-tell and lunch.

It’s the first Saturday in April, and about fifteen members of the approximately one-hundred-member African American Quilt Guild of Oakland are gathered at the home of Marion Coleman in order to share their stories and their quilts with me. A couple of months earlier, Marion spread the word about my visit and graciously offered her home in Castro Valley for our get-together.

The guild has been meeting at the West Oakland Library on the fourth Saturday of every month except December since its founding in June 2000, so this is an extra event on their calendar. The agreement with the library is that they can convene in their meeting room monthly in exchange for hosting a community workshop and exhibit there every winter, which the guild carries out—proudly and happily—during Black History Month in February.

I first learned about AAQGO in the New York Times, where I read about their project Neighborhoods Coming Together: Quilts Around Oakland. This ambitious multiyear, grant-funded undertaking, the brainchild of Marion, included a citywide rotating exhibit of one hundred narrative quilts about life in Oakland, past and present, plus free workshops. The quilts, all stitched by guild members or community members who participated in the guild’s workshops, were divided into groups and made their way through a circuit of exhibition spaces—in places as diverse as the rotunda at city hall, an art gallery, a senior center, a library, elementary schools, and a women’s cancer resource center.

Marion at work at one of the six sewing machines in her home studio. She likes to invite other quilters to join her there for what she calls a “playdate,” a chance to practice new techniques.

“I see my role as trying to empower people to know that they have talent. They can enjoy it and they can push themselves to try something different without being afraid, because it’s all right to make mistakes.”

—Marion Coleman

We fill Marion’s living room, and one by one, members speak about the role of quilting and the guild in their lives. Nearly everyone expresses their gratitude to Marion for inspiring them to explore their creativity—and their appreciation of the camaraderie, skill building, and community service that are key to the guild’s mission. “I see my role as trying to empower people to know that they have talent. They can enjoy it and they can push themselves to try something different without being afraid, because it’s all right to make mistakes,” Marion says. Dolores Vitero Presley and Julia Vitero, founding members and sisters, have just finished teaching an elementary school of more than four hundred students how to quilt, visiting each classroom three times over the course of three weeks, waking at 6:00 a.m. to arrive for the morning bell and threading needles for the kids during lunch breaks. “We complain, but we love it,” says Dolores. “Anything to do with kids, count me in. Teaching them is a way I can give back to the universe.”

Niambi Kee taught herself to quilt from books at the Brooklyn Public Library after her now-grown daughters were born, and she joined the guild as soon as she relocated from Brooklyn to California upon retirement. “I knew I would have an immediate family,” she says. Today she likes combining commercial cloth with cloth she dyes herself to make quilts that reflect her ideas and experiences. She describes one she made in response to the Quincy Jones song “The Midnight Sun Will Never Set” and another she is planning based on the Maya Angelou quote “Try to be a rainbow in someone else’s cloud.”

Frances Porter, the guild’s oldest member at ninety-two, began quilting about ten years ago and has been entering her quilts in the county fair ever since (the first year, her quilt was panned, she says with a laugh, but the second year, she took first prize). She has also donated quilts to her church and sorority and to schools for fund-raisers. Every year during Black History Month, she takes an Underground Railroad–themed quilt to local schools and reads a book about a runaway slave child using quilts as signs of safe houses along her route to freedom. About the guild, she says, “It is very rewarding at my age to meet a group of ladies, all of whom are younger than me, with whom I have a lot in common.” “Each one, teach one” is a guild motto, she explains, and she enjoys sharing what she learns at the guild with others.

Katie Wishom created her Obama quilt—out of T-shirts she collected during the 2008 presidential campaign—as an heirloom for her grandchildren. “I wanted it to represent the pride and happiness I was feeling,” she says.

Although membership is open to all, the majority of members are African American women, many retired with grown children. For a long time, member La Quita Tummings belonged to a different guild, where she was one of only a few African American members. At the AAQGO, she feels more of a sisterhood, she says. “It’s like having aunties and sisters. When we have a conversation, there are some things I don’t have to explain because of our shared experiences as black women.”

On the other hand, Ernestine Tril (who goes by Ernie) is Hispanic; about her guild “sisters,” she says, “They get me.” She joined AAQGO during a difficult time, after the death of her mother, when, she recalls, she was both working and drinking too much. “Quilting helped heal me,” she says. “It took my mind off things. It gave me something else to do, an incentive.” She is especially proud of her contribution to the Neighborhoods Coming Together project, for which she created three quilts, and for her service on the guild’s board, acting as the Northern California Quilt Council liaison. Marion got her involved. “I’m shy. If it weren’t for Marion, I’d probably still be hiding away,” she says. Marion has a knack for drawing people out, honed during the twenty-five years she spent working as a social worker. “I like it when people are able to realize how talented they are,” she says modestly.

Nonagenarian Frances Porter stands proudly before her Butterflies in Spring quilt.

“It is very rewarding at my age to meet a group of ladies, all of whom are younger than me, with whom I have a lot in common.”

—Frances Porter

Marion learned to sew as a young child and started quilting as an adult when she discovered African-print fabrics and photo transfers that allowed her to make a memory quilt for her mother for her seventieth birthday. The walls of her home and her well-equipped studio bear witness to her ongoing dedication to the medium. With her quilts, she documents family memories, commemorates individuals and events in African American history and culture (such as the sole African American explorer on the Lewis and Clark expedition and the election of President Barack Obama), and comments on social issues like racism, homelessness, gun violence, and aging. She teaches and lectures widely, and in 2018, in recognition of her accomplishments and her commitment to keeping the tradition of quilt making alive, she was named a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellow, a prestigious honor that began with a nomination by guild member Ora Clay. In the nomination letter, Ora, who was once an apprentice to Marion under an Alliance for California Traditional Arts program, wrote, “She is passionate in her belief that all of us should enjoy the beauty of art and our individual ability to explore our creative selves.”

That guild-wide exploration is on display for me to see as each member reveals a quilt during our show-and-tell. Most of the projects the women unfold for me are wall quilts, as they tend to be smaller and easier to transport than bed quilts. Many of them would be identified as “art quilts” in the nomenclature of the quilt universe, as they do not rely on the classic patterns of what is commonly considered traditional American quilting, such as log cabins and flying geese. Instead, according to Marion, they draw upon “a long tradition of improvisational and narrative quilting within the African American community” to tell personal stories within a less uniform structure.

Carolyn Pope hand-stitching during our gathering.

Ora Knowell’s quilts tell important—albeit painful—stories, and they’re not small. In fact, on this day she brought the largest quilt I have ever seen in person, at about two feet tall and more than sixty feet long. It is called Homicide and is composed of seventy panels, each one appliquéd with a human form to commemorate a person killed by gun violence. Ora learned to quilt as a child when homemade bedcoverings, patched together from worn-out wool and cotton clothing, were a necessity to keep warm. She began to quilt again as an adult for a very different reason: as a way to process and channel her grief after two of her sons were murdered, one in 1995 and the other in 2002. “The guild brought me out of my shell to be able to share my artwork,” Ora says. “It comes from a dark but good place and is spiritually motivating for a lot of people.” Ora is politically active and regularly attends national antiviolence conferences and local rallies to exhibit and talk about her quilts and sometimes to give workshops to help others, including survivors of violent crime, victim advocates, first responders, and those mourning loved ones. “I teach them nine-block piecing to help redirect their inner pain. They tell me it helps them relax and manage their stress. Now I realize why the adults kept us busy quilting as kids, because of all the pain and suffering they experienced on the plantations; doing something tangible and useful was a mind keeper.”

Before we break for lunch, we go outside together to open Ora’s quilt to its full length. The guild members stand tall, holding the fabric in front of their bodies, proud of the creativity, strength, culture, families, and history they represent. They support one another in good times and bad. They teach and inspire. They laugh. And they open their arms and their hearts to welcome me—and anyone else who cares to come into their embrace. Together, we are a patchwork, a quilt, a community.

Barbara Fuston specializes in nontraditional quilts featuring geometrics and optical illusions. These days she makes her quilts two sided to consolidate the bounty of work she produces.

After Zondra Martin took a workshop with members Dolores Vitero Presley and Julia Vitero at her senior center as part of the Neighborhoods Coming Together project, she decided to join the AAQGO. Here she is hand-stitching a traditional gingham quilt that she brought to the meeting.

One section of Marion’s Melody Makers quilt, a celebration of the integral role music plays in African American culture.

From left to right, Dolores, Katie, and Rosita Thomas admiring a sampler quilt made with blocks stitched by various members. Part of the guild’s mission is to donate quilts to worthy causes: this one went to Meals on Wheels.

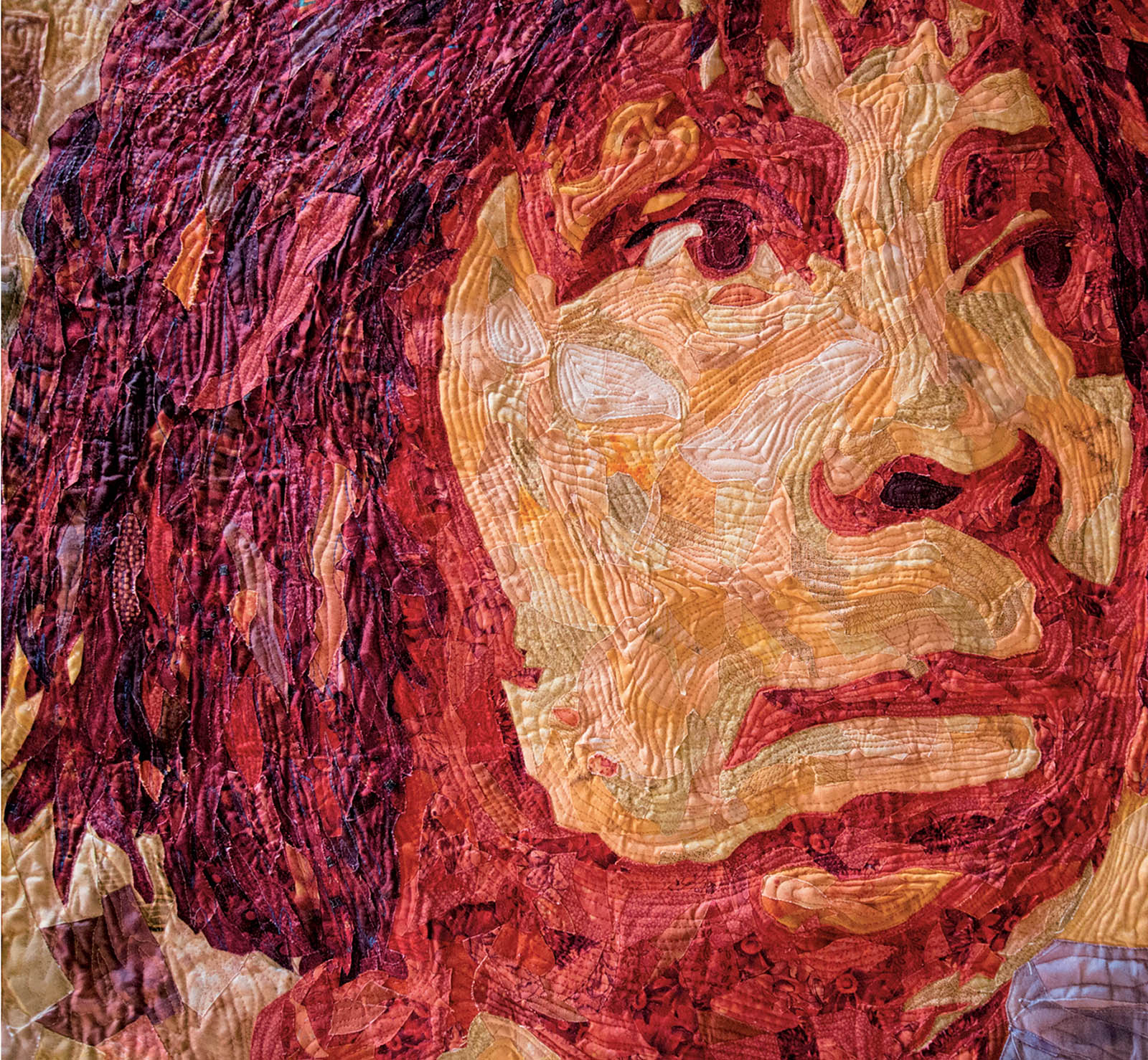

Marion made Hot Flash, a self-portrait based on a photo she took of herself while she was going through menopause.

Dolores (left) holding Leaf One, a paper-pieced quilt she made from a pattern by Judy Niemeyer. About the process, she says, “It was tedious, but it taught me to be patient.” Next to her is her sister Julia, with a quilt she made based on an Ozark cobblestone pattern for which she found a faded clipping—a picture and two templates (but no instructions)—from a newspaper dated 1936. She stitched it by hand over the course of five years.

Inspired by happy memories of growing up in Oakland, Ernestine Tril made this quilt for the guild’s Neighborhoods Coming Together project. “All the kids—Hispanic, Anglo, African American, and Asian—would play together,” she remembers, calling from their windows when they were ready to go outside to meet up.

Niambi Kee combines commercial and hand-dyed fabrics in her quilts (and sometimes her clothing). The quilt shown here, called Parenting Near Lake Manyara, recounts a trip to Tanzania many years ago when, she says, “I had the privilege and honor to witness a herd of elephants going across the savanna. What especially impressed me then as a young parent was the way the babies were protectively tucked between the massive legs of the matriarchs.”

Carolyn made this quilt, called We the Women of Color, to represent “women of color in all their shapes and hues and personalities. It shows how beautiful we are inside and out,” she says.

Carolyn's Spider Mandala quilt uses all types of media, including string and tulle lamé, with a spirit figure on top.

“It’s like having aunties and sisters. When we have a conversation, there are some things I don’t have to explain because of our shared experiences as black women.”

—La Quita Tummings

Ora Knowell holds a section of her Homicide quilt about gun violence. She regularly takes it with her to antiviolence events in California and elsewhere. People who have lost family and friends to gun violence add their loved ones’ names in marker.

Along Marion’s driveway, guild members hold up Homicide outstretched to its full sixty-plus feet.

Detail from Hope for the Future, a quilt Ora Knowell made as part of the guild’s annual Black History Month exhibition at the West Oakland public library. According to Ora, the marchers at the top recognize the struggles of the past (depicted along the bottom) but march forward in order to effect positive change for the future.